Abstract

A treatment of the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum with high light (HL) in the visible range led to the conversion of diadinoxanthin (Dd) to diatoxanthin (Dt). In a following treatment with HL plus supplementary ultraviolet (UV)-B, the Dt was rapidly epoxidized to Dd. Photosynthesis of the cells was inhibited under HL + UV-B. This is accounted for by direct damage by UV-B and damage because of the UV-B-induced reversal of the Dd cycle and the associated loss of photoprotection. The reversal of the Dd cycle by UV-B was faster in the presence of dithiothreitol, an inhibitor of the Dd de-epoxidase. Our results imply that the reversal of the Dd cycle by HL + UV-B was caused by an increase in the rate of gross Dt epoxidation, whereas the de-epoxidation of Dd was unaffected by UV-B. This is further supported by our finding that the in vitro de-epoxidation activity and the affinity toward the cosubstrate ascorbic acid of the Dd de-epoxidase were both unaffected by UV-B pretreatment of intact cells. We provide evidence that Dt epoxidation is normally down-regulated by a high pH gradient under HL. It is proposed that supplementary UV-B affected the pH gradient across the thylakoid membrane, which disrupted the down-regulation of Dt epoxidation and led to the observed increase in the rate of Dt epoxidation.

In higher plant leaves exposed to strong light, part of the violaxanthin is converted to zeaxanthin in a two-step de-epoxidation via the intermediate antheraxanthin (Yamamoto et al., 1962). This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme violaxanthin de-epoxidase, which is localized in the thylakoid lumen space and is activated at low pH (Hager, 1969; Pfündel and Dilley, 1993). In weak light or in the dark, the zeaxanthin epoxidase catalyzes two successive epoxidation steps from zeaxanthin to violaxanthin, which complete the violaxanthin cycle. Besides higher plants, this cycle is also found in the chlorophyta and the phaeophyceae (Stransky and Hager, 1970). In these plants, zeaxanthin is supposed to protect PSII through thermal dissipation of surplus absorbed quantum energy (Demmig et al., 1987; Duval et al., 1992; Maxwell et al., 1995; for review, see Demmig-Adams and Adams, 1993, 1996; Yamamoto and Bassi, 1996; Gilmore, 1997). However, in some green algae, no relation was found between thermal dissipation and zeaxanthin (Casper-Lindley and Björkman, 1998; Masojidek et al., 1999). In agreement with the localization of the violaxanthin cycle on pigment proteins of the PSII antenna (Bassi et al., 1993; Ruban et al., 1994; Goss et al., 1997), it was shown in time-resolved fluorescence decay studies that the non-photochemical quenching of chlorophyll (Chl) excited states by zeaxanthin is also attributed to the PSII antenna (Gilmore et al., 1995; Wagner et al., 1996; Richter et al., 1999). Two main hypotheses on the mechanism of the thermal dissipation have been proposed. According to Horton et al. (2000), zeaxanthin has an indirect role through allosteric down-regulation of light harvesting. Alternatively, zeaxanthin may be a direct quencher of the first excited state of Chl a because of a lower lying, formally dipole forbidden excited state (Frank et al., 1994; Owens, 1994). By the use of mutants defective in non-photochemical quenching, Li et al. (2000) were able to show that in addition to zeaxanthin, the psbS gene product is essential for thermal dissipation in the light-harvesting antenna.

There is growing evidence that zeaxanthin has further roles in photoprotection besides regulation of light harvesting in PSII. It protects thylakoid lipids against photooxidation (Havaux and Niyogi, 1999) and provides enhanced heat stability to the lipid matrix and PSII by decreasing thylakoid membrane fluidity (Havaux and Gruszecki, 1993).

In diatoms, dinophytes, and haptophytes, the violaxanthin cycle is replaced by the diadinoxanthin (Dd) cycle in which Dd is converted to diatoxanthin (Dt) by only one de-epoxidation step in strong light (Stransky and Hager, 1970). Several of these microalgal species may also contain substantial amounts of the violaxanthin cycle pigments after prolonged exposure to strong light (Lohr and Wilhelm, 1999). It has been shown that the Dd cycle has a function in thermal dissipation similar to the violaxanthin cycle (Arsalane et al., 1994; Olaizola and Yamamoto, 1994; Olaizola et al., 1994; Frank et al., 1996).

The objective of the present study was to investigate possible effects of UV-B radiation on the Dd cycle in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. It is shown that supplementary UV-B causes a reversal of the Dd cycle in strong light-exposed cells. The associated loss in photoprotection makes cells more susceptible to photoinhibition by photosynthetically active radiation. We provide evidence that UV-B acts through disruption of a down-regulation mechanism for Dt epoxidase that is related to a high pH gradient across the thylakoid membrane.

RESULTS

UV-B (under Strong Light) Affects the Dd Cycle

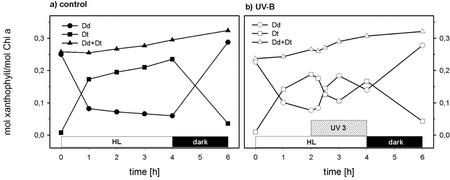

Before the high light (HL) treatment, the cell suspensions of P. tricornutum had a high content of Dd and a low content of Dt, which is typical of cells adapted to the dark or low light (Fig. 1, a and b). In the control cells (Fig. 1a), there was a strong increase in Dt and a corresponding decrease of Dd within the 1st h of HL. After that, Dt increased at a low rate because of continuing de-epoxidation of existing Dd but also because of de-epoxidation of newly formed Dd. The de novo synthesis of Dd started in the HL treatment but continued in the subsequent dark period and led to a 20% increase in the Dd cycle pool size [(mol Dd + Dt)/mol Chl a]. During the 2 h of dark treatment, most of the Dt was epoxidized.

Figure 1.

The time course of the amounts of Dd and Dt in suspensions of P. tricornutum exposed to HL + UV 3. After 30 min of dark adaptation, the control cells (a) were exposed for 4 h to HL (photosynthetic photon flux density [PPFD] 300 μmol m−2 s−1) without UV-B and then again dark adapted for 2 h. The UV-B treatment (b) consisted of 2 h of exposure to HL followed by 2 h of HL + UV 3 and 2 h of recovery in the dark. The irradiance of the supplementary UV 3 was 2.3 W m−2 at the front of the cuvette corresponding to a mean irradiance of 0.82 W m−2. The Chl a and c content was 2 mg L−1. The curves represent the average of two independent experiments.

When supplementary UV 3 was applied after 2 h of HL, a sharp drop in Dt and a corresponding steep increase in Dd indicated a high rate of Dt epoxidation despite continuing HL (Fig. 1b). After 1 h of supplementary UV 3, the situation changed again and Dt increased at the cost of Dd until HL and UV 3 were switched off. The cells treated with HL or HL + UV 3 contained similar contents of Dd and Dt after 2 h of dark recovery. There was no significant difference between UV 3-treated and untreated cells in the Dd cycle pool size, which indicates that Dd cycle pigments and Chl a were not specifically degraded even with the highest intensity of UV-B applied in this study. There was also no significant decrease in the Chl a content after 2 h of HL + UV 3 (not shown).

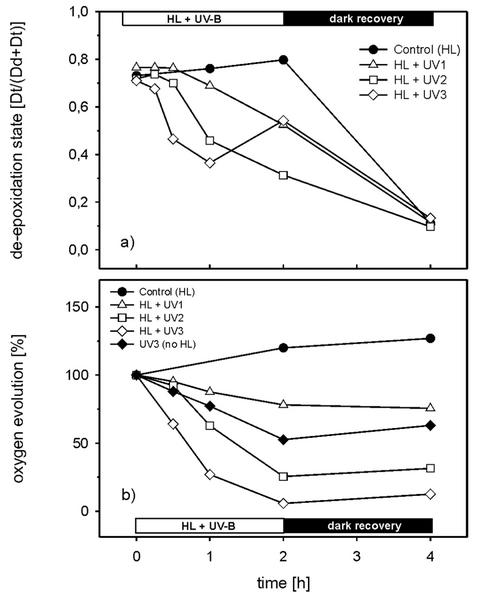

In Figure 2a, the time course of the DES [Dt/(Dd + Dt)] of the HL- and HL + UV-B-treated cells is depicted. At the beginning of the HL + UV-B treatments, the cell suspensions all had a high DES of more than 0.7 because of the 2 h of HL pretreatment. Continual HL treatment without UV-B led to a slow increase in the DES in control cells up to 0.8. When the supplementary UV-B radiation UV 1 (HL + UV 1) was applied, the DES decreased to 0.52 (65% of control), even though the cells were still exposed to HL. The reversal of the Dd cycle was more pronounced in the combined HL + UV 2 treatment where the DES eventually decreased to 0.32. The highest initial rate of Dt epoxidation was observed with the combined HL + UV 3 treatment. The DES dropped to 0.36 within 1 h but then it rose again to 0.54 at the end of the HL + UV 3 exposure. In the 2-h dark period subsequent to the combined HL + UV-B treatment, a low DES of around 0.1 to 0.13 was reached in all samples (Fig. 2a). The complex kinetics of the DES under HL + UV 3 pointed to direct inhibition of the Dt epoxidase by UV-B, which was further investigated by measurements of dark epoxidation in cells that had been pretreated under various UV-B irradiances.

Figure 2.

a, Time course of the de-epoxidation state (DES) [Dt/(Dd + Dt)]; b, photosynthetic oxygen evolution during combined treatment of cells with HL and different irradiances of supplementary UV-B. Before HL + UV-B treatment, all cells were HL adapted for 2 h. For the samples of UV 3 (no HL) in b, the HL was omitted during exposure to UV 3. The Chl a and c content was 2 mg L−1. The rates of oxygen evolution were normalized to the value after 2 h of HL pretreatment. One-hundred percent oxygen evolution corresponds to 160 μmol O2 mg−1 Chl h−1. Samples for the measurement of the oxygen evolution and the DES were taken from identical suspensions. The curves represent the average of two independent experiments.

UV-B Affects Protection against Strong Light

There was a small increase of photosynthetic oxygen evolution measured at 300 μmol m−2 s−1 throughout the whole HL treatment (control), indicating that the applied PPFD was not photoinhibitory to the cells (Fig. 2b). The combined HL + UV-B treatments led to losses in oxygen evolution of 21% (HL + UV 1), 71% (HL + UV 2), and 94% (HL + UV 3) after 2 h. The exposure of cells to UV 3 without HL caused significantly lower decreases in oxygen evolution as compared with the combined HL + UV 3 and HL + UV 2 treatments.

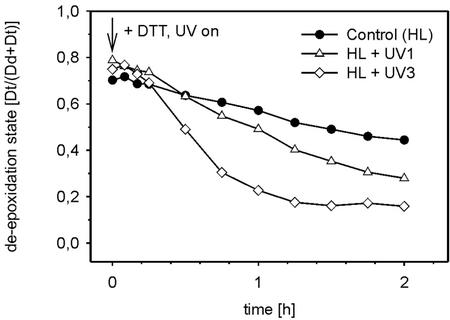

UV-B (under Strong Light) Increases the Rate of Dt Epoxidation

Three of the HL + UV-B treatments described in Figure 2a were repeated in the presence of 10 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), an inhibitor of Dd de-epoxidase, to distinguish between possible UV-B effects on Dd de-epoxidation and Dt epoxidation. Using intact cells, it proved to be necessary to use DTT at 10 mm to achieve complete inhibition of Dd de-epoxidation (not shown). Before the start of the HL + UV + DTT treatments, high DESs between 0.70 and 0.79 were established by 2 h of HL pretreatment (Fig. 3). After the addition of DTT, the DES decreased only from 0.7 to 0.44 within 2 h in the control (HL + DTT). Such a slow rate of Dt epoxidation indicated a possible down-regulation of Dt epoxidase. In samples at HL + UV 1 + DTT and HL + UV 3 + DTT, the DES decreased faster. In the control and HL + UV 1 + DTT sample, the Dt epoxidation continued throughout the whole treatment. Sample HL + UV 3 + DTT showed the highest initial Dt epoxidation activity, but after 1.5 h, Dt epoxidation stopped at a DES of about 0.15. Specific information on Dd de-epoxidation under HL and UV-B may be derived from the extent of the DTT-induced loss in the DES at a particular time point, i.e. the larger the loss, the higher the de-epoxidation activity in the corresponding DTT untreated sample. The comparison between a particular HL + UV-B treatment in Figure 2a and the respective HL + UV-B + DTT treatment in Figure 3 already reveals DTT-induced losses in the DES in all samples, whether UV-B treated or not. For a calculation of the relative losses in the DES by DTT in each of the three HL + UV-B treatments (HL + DTT versus HL, HL + UV 1 + DTT versus HL+ UV 1, and HL + UV 3 + DTT versus HL + UV 3) and also for a quantitative comparison of these losses between different samples, the small variations in DESs after 2 h of HL pretreatment were first eliminated by normalization of the DESs at a given time point of the combined HL + UV-B (±DTT) treatment to the respective value at the beginning of the experiment. Then Δt, the percentage DTT-induced loss in the DES at time t was calculated as the difference between the normalized DES in the absence and in the presence of DTT according to:

|

where DES0 and DESt denote the DES at the beginning and at time t of the treatment, respectively.

Figure 3.

The time course of the DES [Dt/(Dd + Dt)] during combined treatment of cells with HL and different irradiances of supplementary UV-B. Before HL + UV-B treatment, all cells were HL adapted for 2 h. The Chl a and c content was 2 mg L−1. At the start of the UV-B exposure, the Dd de-epoxidase was inhibited by the addition of 10 mm DTT to the suspensions. The experiment was repeated three times. The sd did not exceed 6%.

Table I shows the respective results for 1- and 2-h treatments. It is obvious that DTT led to similar values of Δt in the two UV-B-treated samples and in the untreated control (HL) after 1 h. Although there is more variation in Δt after 2 h, the large DTT-induced decreases in DES in all samples show that there must have been considerable de-epoxidation activity in all DTT-untreated samples described in Figure 2a, whether UV-B treated or not.

Table I.

The DES under HL + UV-B in the presence and absence of DTT

| Time of HL + UV-B Pretreatment | Normalized DES (DESt/DES0)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (HL)

|

HL + UV 1

|

HL + UV 3

|

|||||||

| −DTT | +DTT | Δt | −DTT | +DTT | Δt | −DTT | +DTT | Δt | |

| h | % | ||||||||

| 1 | 104.0 | 81.4 | 22.6 | 89.9 | 62.4 | 27.5 | 51.3 | 30.4 | 20.9 |

| 2 | 109.0 | 63.3 | 45.7 | 68.5 | 35.5 | 33.0 | 75.9 | 21.8 | 54.1 |

The cells were first exposed to HL for 2 h at a Chl a and c content of 2 mg L−1 and were then treated for 2 h with HL or HL + UV-B in the presence or absence of DTT, an inhibitor of the Dd de-epoxidase. The values of the DES after 1 and 2 h of the combined HL + UV-B treatment (DESt) were taken from Figures 2a and 3 and were normalized to the values at the start of the respective HL + UV-B treatment (DES0). DES0 ranged between 0.70 and 0.79. The normalized DESs [DESt/DES0] are given in percent and were used to calculate the DTT-induced decreases of the DESs (Δ t) in HL- or HL + UV-B-treated cells.

UV-B Does Not Affect the in Vitro De-Epoxidation Activity

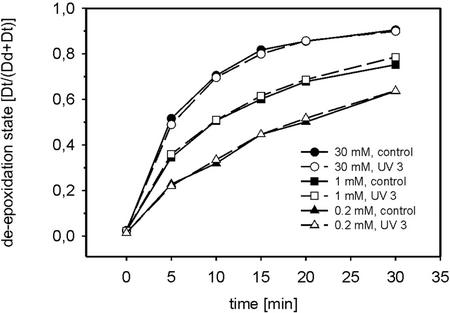

The results in Figures 2a and 3 and Table I suggest that the UV-B induced reversal in the Dd cycle is caused by an enhanced rate of Dt epoxidation, whereas Dd de-epoxidation seemed to be unaffected. Dd de-epoxidation activity was also examined in vitro. For this purpose, 2-h UV 3-pretreated and untreated cells were disrupted by five freeze-thaw cycles and then allowed to perform in vitro Dd de-epoxidation at pH 5.5. The three different concentrations of the de-epoxidase cosubstrate ascorbic acid used in the in vitro assays (30, 1, and 0.2 mm) are supposed to range from saturation to strong limitation of Dd de-epoxidation. It is obvious that with all three ascorbic acid concentrations, the de-epoxidation kinetics were identical in control and respective UV 3-pretreated samples (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

In vitro Dd de-epoxidation in broken P. tricornutum cells. The cell suspensions were pretreated with UV 3 for 2 h at a Chl a and c content of 2 mg L−1. Controls were kept in the dark. The cells were then collected by centrifugation, resuspended in a small volume of a medium buffered at pH 6.5, and broken by five freeze-thaw cycles. After dilution in a medium buffered at pH 5.5, the de-epoxidation was started by the addition of indicated concentrations of ascorbic acid. The experiments were repeated three times with dual measurement at every time point. The sd was less than 5%.

Dt Epoxidation Is Down-Regulated under Strong Light by the Proton Gradient

The finding that gross Dt epoxidation was very slow in HL + DTT-treated cells suggests an effective, though yet unknown, mechanism for down-regulation of the Dt epoxidase in HL-treated cells (Fig. 3). The increases in Dt epoxidation with supplementary UV-B provided evidence that this mechanism was sensitive to UV-B. We checked for a possible role of the proton gradient across the thylakoid membrane in down-regulation of the Dt epoxidase, which might have been affected by UV-B in our experiments. This assumption is based on earlier observations that UV-B is able to disrupt cellular membranes (Brandle et al., 1977) and makes thylakoids leaky to ions (Chow et al., 1992).

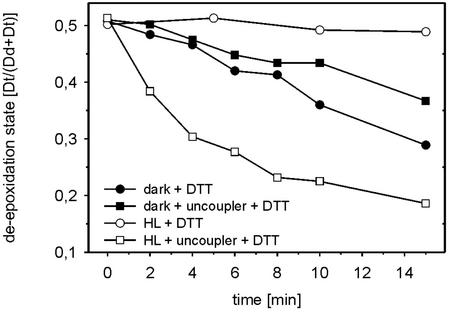

P. tricornutum cells were first exposed for 30 min to HL to establish a high de-epoxidation level. Then DTT was added to achieve complete inhibition of Dd de-epoxidase. No epoxidation was induced within 15 min (Fig. 5). A slow epoxidation occurred in the dark. The previously formed Dt was epoxidized at a maximal rate when the uncoupling reagents ammonium chloride and nigericin were added to the cells under HL condition. In dark-treated cells, the uncoupling caused only a slight but significant decrease of the Dt epoxidation rate.

Figure 5.

The influence of the proton gradient on Dt epoxidation in P. tricornutum cells. A DES [Dt/(Dd + Dt)] of approximately 0.5 was established in all cells by 30-min HL pretreatment. Thereafter, the Dd de-epoxidation was stopped by the addition of 10 mm DTT and the Dt epoxidation was observed in continued HL treatment as well as in the dark. The influence of uncoupling on Dt epoxidation in HL- and dark-treated cells was checked by the addition of uncoupler (25 mm ammonium chloride + 100 μm nigericin). The curves represent the average of two experiments with dual measurement at every time point.

UV-B Decreases the Dark Dt Epoxidase Activity

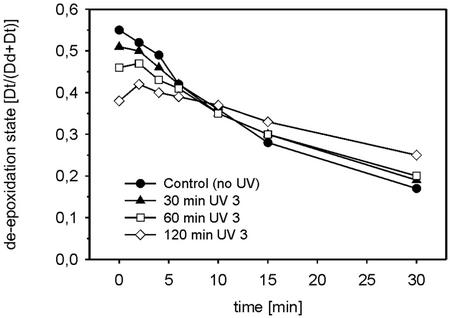

The results obtained with HL + UV 1 and HL + UV 2 (Figs. 2a and 3) are fully consistent with the hypothesis that the observed reversal of the Dd cycle is caused by enhanced Dt epoxidase activity. However, the respective increases of Dt and of the DES during the 2nd h under HL + UV 3 in Figures 1 and 2a seems to contradict this hypothesis. We suspected that the UV-B sensitivity of the Dt epoxidase caused the complex kinetics of the DES in sample HL + UV 3. The complete loss of Dt epoxidase activity after 1.5 h of HL + UV 3 + DTT treatment in Figure 3 points already to a possible direct inhibition of Dt epoxidase by UV-B. This inhibition could finally surpass the potential stimulation of Dt epoxidase, which would result from a decrease in the proton gradient. We checked for a possible inhibition of Dt epoxidase with cell suspensions treated 0.5, 1, and 2 h with UV 3. After the UV-B treatment, the cells were exposed for 15 min to PPFD of 800 μmol m−2 s−1 until a high level of Dt was attained and then kept in the dark. At the end of the HL treatment and during the following dark incubation, samples were withdrawn to measure their DES. As expected, the UV-B-pretreated samples reached lower final levels of Dt after the HL treatment, which might account for part of the observed decreases in the initial epoxidation rates shown in Figure 6. However, after 10 min in the dark, when all samples had similar Dt contents, there was still a significant inhibition of Dt epoxidation in the 2-h UV 3-treated samples. With increasing duration of the UV 3 pretreatment, there was also a delayed onset of Dt epoxidation after HL was turned off. The 1- and 2-h UV 3-treated cells showed a continued net Dd de-epoxidation in the first 2 min of the dark incubation.

Figure 6.

The inhibition of dark Dt epoxidation in P. tricornutum cells after different periods of UV 3 treatment. The cells were first exposed to UV 3 for 30, 60, and 120 min. The cells were then exposed to a PPFD of 800 μmol m−2 s−1 for 15 min to establish a high DES and then kept in the dark. The decrease of the DES in the dark was followed for 30 min. The curves represent the average of two experiments with dual measurement of the DES at the different time points.

DISCUSSION

UV-B (under Strong Light) Decreases Photoprotection by Enhanced Dt Epoxidation

A UV-B effect on xanthophyll cycles of algae cannot be observed, when the supplementary UV exposure is performed under low-growth light conditions, which is usually applied in the culture of algae. In our study, P. tricornutum cells were first allowed to acclimate to supersaturating white light (HL) before being exposed to HL plus increasing UV-B radiations. The HL pretreatment led to the expected conversion of Dd to Dt. Supplementary UV-B caused a reversal of the Dd cycle and also a loss in photosynthetic oxygen evolution. The initial rate of decrease in the DES and the loss in oxygen evolution depended on the UV-B radiant flux density (Fig. 2, a and b). However, only part of the observed loss in oxygen evolution was directly caused by UV-B. Further loss under combined HL + UV-B exposure was related to HL and resulted from the decreased DES and the associated lack of photoprotection against supersaturating light. This is clearly demonstrated by the fact that UV 3 alone caused only one-half of the loss in oxygen evolution as the combined HL + UV 3 treatment, whereas HL by itself did not cause any loss in activity (Fig. 2b). This proves the photoprotective function of the Dd cycle in P. tricornutum, which had been questioned in an earlier study (Olaizola et al., 1994).

The UV-B treatment caused no degradation of Dd cycle pigments because the sum of Dd and Dt on a Chl a basis and the Chl a content were the same in UV-B-treated and untreated control samples at any time point during the treatments (Fig. 1). The observed net increase in Dt epoxidation under HL + UV-B resulted from an increased rate of gross Dt epoxidation, whereas the actual rate of Dd de-epoxidation was insensitive to UV-B. This is concluded from the following observations: (a) The increase in the rate of Dt epoxidation by UV-B was also seen in cells inhibited in Dd de-epoxidation by the addition of DTT (Fig. 3), (b) The losses in the DES induced by DTT were similar in UV-B-treated and untreated cells (Table I), and (c) The identical in vitro de-epoxidation kinetics in cells pretreated and untreated with UV 3 also show that neither the maximum potential activity of Dd de-epoxidase nor the affinity of the enzyme toward its cosubstrate ascorbic acid were affected. The identical de-epoxidation kinetics also prove that UV 3 did not influence the availability of Dd for de-epoxidation (Fig. 4).

The Proton Gradient Is Involved in Down-Regulation of Dt Epoxidase

A direct stimulation of Dt epoxidase by UV-B is an unlikely explanation for the observed increase in gross Dt epoxidation under HL + UV-B + DTT (Fig. 3). We propose a partial loss in the pH gradient induced by UV-B as the reason for the enhanced Dt epoxidation activity in HL + UV-B-treated cells. This suggestion is based on our finding that the Dt epoxidase was strongly down-regulated under HL by a high pH gradient and on the known effect of UV-B to make thylakoids leaky to ions (Chow et al., 1992).

There is clear evidence for the proposed down-regulation of the Dt epoxidase by a high pH gradient from measurements of the rate of Dt epoxidation in HL-pretreated cells. When the cells were treated by adding DTT to stop Dd de-epoxidation, the rate of Dt epoxidation was extremely low despite high levels of Dt and supposedly high levels of the cosubstrates oxygen and NADPH. The rate was even lower than in cells kept in the dark in the presence of DTT, in which epoxidation was more likely limited by cosubstrate levels than in HL-treated cells. In support of down-regulation by the pH gradient, the rate of Dt epoxidation was maximal upon the addition of uncoupler to HL + DTT-treated cells. The lower Dt epoxidation rates obtained with uncoupling in the dark are possibly because of competition for reducing equivalents by uncoupled dark respiration.

It is not known how a pH gradient is linked to down-regulation of the Dt epoxidase. A direct regulation of the stromal enzyme by the pH gradient is unlikely because of the fact that the light-induced pH changes in the chloroplast stroma are rather small. In addition, the down-regulation of Dt epoxidase by a pH gradient seems to be in contradiction to the earlier finding of a distinct pH optimum near 7.5 for the homologous enzyme zeaxanthin epoxidase from higher plants (Hager, 1975; Siefermann and Yamamoto, 1975). Alternatively, a high pH gradient could cause a lower availability of Dt for the epoxidase. The epoxidation of Dt depends on a flip-flop of the molecule through the membrane to make the de-epoxidized end group accessible to the epoxidase. In P. tricornutum, this is possibly no rate-limiting step for epoxidation. During prolonged exposure to HL, this alga converts Dd to Dt but shows also a strong increase in the content of zeaxanthin (Lohr and Wilhelm, 1999). The measured rate constants of subsequent epoxidation of zeaxanthin to antheraxanthin and Dt to Dd under low light were nearly the same for both de-epoxidized xanthophylls, although Dt has to flip-flop through the membrane first (Lohr and Wilhelm, 2001). On the other hand, Gilmore et al. (1994) provided clear evidence that there can be a competition between the epoxidase and the site of non-photochemical quenching for binding zeaxanthin and antheraxanthin under HL. Assuming that a high pH gradient could enhance the affinity of Dt to its binding site in quenching, such a competition could also explain the limited Dt epoxidation in our HL + DTT-treated algae.

UV-B Decreases Dark Dt Epoxidation

The changes in the DES observed under HL + UV 1 and HL + UV 2 are consistent with our view that supplementary UV-B causes a reversal of the Dd cycle under HL by enhanced gross Dt epoxidation. However, this hypothesis does not sufficiently explain why the DES only decreased during the 1st h of HL + UV 3 treatment but rose again during the 2nd h (Fig. 2a). It is supposed that the initial decrease was caused by enhanced Dt epoxidase activity, which resulted from partial uncoupling of the thylakoid membrane by UV-B. The subsequent increase in the DES could be because of slow restoration of the pH gradient as a consequence of a reduced ATP demand by photosynthetic dark reactions including a possible inhibition of the ATP synthase (Zhang et al., 1994). This explanation would be in agreement with the strong inhibition of oxygen evolution under HL + UV 3. On the other hand, we observed that the dark Dt epoxidase activity was slowly inhibited by UV-B, which could have resulted from a direct inhibition of the enzyme or the inhibition of processes involved in the production of NADPH in the dark. This slow inhibition of the enzyme could have counteracted its potential up-regulation associated with partial uncoupling of the thylakoid membrane by UV-B. As a result, the Dt epoxidation was finally surpassed again by the UV-B insensitive Dd de-epoxidation.

Our view that UV-B induced uncoupling leads to enhanced Dt epoxidase activity without affecting the Dd de-epoxidase is at first glance contradictory to the accepted view of the role of the pH gradient in the activation of violaxanthin de-epoxidase (Hager, 1966; Pfündel and Dilley, 1993; Hager and Holocher, 1994). However, it has been shown recently that the Dd de-epoxidase in P. tricornutum is actually activated at much higher pH values than the violaxanthin de-epoxidase (Jakob et al., 2001). This pH dependence might explain the high Dd de-epoxidase activity despite UV-B-induced decreases in the pH gradient.

It has been reported that supplementary UV-B led to enhanced de-epoxidation of Dd in P. tricornutum (Goss et al., 1999) and to enhanced de-epoxidation of violaxanthin in Nannochloropsis gaditana (Neale et al., 2001). Compared with our study, Goss et al. (1999) used the same UV-B source but the HL pretreatment before the start of UV-B was twice as long as in our study. Despite identical PPFD of the HL the resulting DESs after the HL pretreatment were significantly lower than in our study. Neale et al. (2001) used a different UV-B and visible light source. The resulting differences in the spectral irradiance strongly affected the outcome of the combined HL and UV-B treatments. There might also exist differences between species in the balance between the loss of down-regulation in Dt epoxidation and direct inhibition of Dt epoxidase. Because UV-B effects on xanthophyll cycles might have important consequences for natural algal communities, these uncertainties should be sorted out by further research.

CONCLUSION

According to our results, supplementary UV-B radiation causes an increase in the rate of gross Dt epoxidation, which leads to a reversal of the Dd cycle even under continuous HL. This is best explained by assuming that: (a) In the presence of a high pH gradient under supersaturating light (HL) the rate of Dt epoxidation is low because of down-regulation of the Dt epoxidase and/or by causing enhanced competition between the site of non-photochemical quenching and the epoxidase for binding Dt; and (b) UV-B weakens these limitations of Dt epoxidation through a partial loss of the ΔpH.

The associated loss of photoprotection under HL causes an additional decline of photosynthetic activity besides the damage that is directly caused by UV-B.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Phaeodactylum tricornutum (axenic strain 1090-1a; Sammlung von Algenkulturen Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany) was grown at 20°C in batch cultures in a modified ASP 2 medium (Provasoli et al., 1957) at a PPFD of 50 μmol m−2 s−1 and a light/dark cycle of 16/8 h.

Light Treatments

Cell suspensions of P. tricornutum were diluted with culture medium to a Chl a and c content of 2 mg mL−1 as determined in acetone:water (9:1 [v/v]) using the equations of Jeffrey and Humphrey (1975). Then, 200 mL of the suspensions were placed in a cuvette (40 × 40 × 200 mm) made of UV-B transparent acrylic glass (Röhm, Darmstadt, Germany). The suspensions were stirred and in addition bubbled with air at 20°C. Non photoinhibitory strong light in the visible range was supplied by cool-white halogen lamps at a PPFD of 300 μmol m−2 s−1. The UV-B radiation was provided by a UV-B fluorescent lamp (TL20/12, Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands), which had also a minor emission in the UV-A. The UV-C was cut by 0.13-mm cellulose acetate film (Pütz, Taunusstein, Germany), which is opaque to wavelengths <280 nm and was replaced every 2 h of UV-B. UV-B exposures were performed at three different irradiances denoted UV 1 through UV 3, which were adjusted by the distance between the fluorescent lamp and the cuvette. The UV-B irradiance was measured using the UV radiometer Krochmann210 (PRC, Berlin). The UV-B irradiances at the front of the cuvette were: 2.3 W m−2, UV 3; 1.5 W m−2, UV 2; and 0.9 W m−2, UV 1. The depth of the cuvette was 40 mm. Because of the light gradient in the cuvette, the stirred cells were exposed to intermittently changing UV-B irradiances ranging between 2.3 and about 0.2 W m−2 in the case of UV 3. The resulting mean irradiances were 0.82 W m−2, UV 3; 0.54 W m−2, UV 2; and 0.34 W m−2, UV 1. The “mean UV 3” is defined such that the area of a rectangle given by the “mean UV 3” irradiance and the depth of the cuvette is the same as the area under the irradiance versus depth curve of UV 3. The mean UV 2 and UV 1 were calculated accordingly. Before the start of UV-B, the cells were exposed to non-photoinhibitory strong light (HL) for 2 h. Thereafter, UV-B was applied for 2 h, whereas strong light continued (HL + UV-B). After that, the cells were kept in the dark for another 2 h. The control treatment consisted of 4 h of HL followed by 2 h of dark incubation.

Photosynthetic Pigments

During the treatments, samples of 5-mL suspension were withdrawn from the acrylic glass cuvette at the specified times. The cells were harvested by fast filtration (glass fiber filter type 6, Schleicher & Schull, Dassel, Germany) and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. The time needed until freezing did not exceed 0.5 min. After freezing, the samples were lyophilized to remove water. For pigment extraction, the dry filters were placed in a 50-mL duran glass flask of a cell homogenizer (type MSK, Braun, Melsungen, Germany) together with 3 mL of 0.2 m ammonium acetate in methanol:ethyl acetate (9:1 [v/v]) and 3 mL of a mixture of glass beads (0.3- and 1-mm diameter). Before use, the duran glass flask was cooled to −20°C. The pigments were extracted by 30-s operation of the homogenizer with permanent cooling of the glass flask by CO2 snow. The extracts were decanted and the cell debris was removed by 4-min centrifugation in microcentrifuge tubes. The clear supernatant was immediately used for HPLC analysis. The pigments were separated on a Nucleosil 5 C18 column (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) using a ternary eluent system according to Wright and Jeffrey (1997).

In Vitro De-Epoxidation Assay

Dark-adapted P. tricornutum cell suspension (75 mL containing 0.15 mg of Chl) were first treated with UV 3 for 2 h in an acrylic glass cuvette. HL was omitted to prevent light induced de-epoxidation before the start of the in vitro de-epoxidation. After the UV 3 treatment, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 2,000g at 0°C for 5 min. The sediment was resuspended in 1 mL of a solution containing 1 m sorbitol, 5 mm MgCl2, 2 mm KCl, 0.2% (w/v) bovine serum albumin, and 10 mm MES (pH 6.5), and then transferred to a microcentrifuge tube. To break cells and make the de-epoxidase accessible to external ascorbic acid and pH change the suspension was subjected to five freeze-thaw cycles and then stored on ice. Breaking of the cells by freeze-thaw cycles was superior to cell homogenization with glass beads with regard to the maximum rates and extent of de-epoxidation. With regard to the reported pH dependence of the Dd de-epoxidase (Jakob et al., 2001) and assuming a membrane attachment of the active enzyme as with the violaxanthin de-epoxidase (Hager and Holocher, 1994), the breaking of the cells was performed at pH 6.5 to minimize the release of the enzyme from leaky thylakoid lumen space during the freeze-thaw cycles. The de-epoxidation was started by diluting 200 μL of the broken cell suspension in 10 mL of a medium containing 0.33 m sorbitol, 10 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 40 mm MES (pH 5.5), and indicated concentrations of ascorbic acid.

Measurement of Photosynthetic Oxygen Evolution

At the specified times, 1 mL of cell suspension was withdrawn from the acrylic glass cuvette and the photosynthetic oxygen evolution was measured in an oxygen electrode vessel (DW1, Hansatech, King's Lynn, UK) at a PPFD of 300 μmol m−2 s−1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Prof. Christian Wilhelm and Dr. Reimund Goss for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (grant to H.M.) and by the University of Mainz (grant to H.M.).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.006775.

LITERATURE CITED

- Arsalane W, Rousseau B, Duval J-C. Influence of the pool size of the xanthophyll cycle on the effects of light stress in a diatom: competition between photoprotection and photoinhibition. Photochem Photobiol. 1994;60:237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Bassi R, Pineau P, Dainese P, Marquardt J. Carotenoid-binding proteins of photosystem II. Eur J Biochem. 1993;212:297–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandle JR, Campbell WF, Sisson WB, Caldwell MM. Net photosynthesis, electron transport capacity, and ultrastructure of Pisum sativum L. exposed to ultraviolet-B radiation. Plant Physiol. 1977;60:165–169. doi: 10.1104/pp.60.1.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper-Lindley C, Björkman O. Fluorescence quenching in four unicellular algae with different light-harvesting and xanthophyll-cycle pigments. Photosynth Res. 1998;56:277–289. [Google Scholar]

- Chow WS, Strid A, Anderson JM. Short term treatment of pea plants with supplementary ultraviolet-B radiation: recovery time-courses of some photosynthetic functions and components. In: Murata N, editor. Research in Photosynthesis. Vol. 4. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1992. pp. 361–364. [Google Scholar]

- Demmig B, Winter K, Krüger A, Czygan F-C. Photoinhibition and zeaxanthin formation in intact leaves. Plant Physiol. 1987;84:218–224. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.2.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmig-Adams B, Adams WW., III . The xanthophyll cycle. In: Young A, Britton G, editors. Carotenoids in Photosynthesis. London: Chapman and Hall; 1993. pp. 206–251. [Google Scholar]

- Demmig-Adams B, Adams WW., III The role of xanthophyll cycle carotenoids in protection of photosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 1996;1:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Duval JC, Harker M, Rousseau B, Young AJ, Britton G, Lemoine Y. Photoinhibition and zeaxanthin formation in the brown algae Laminaria saccharina and Pelvetia canaliculata. In: Murata N, editor. Research in Photosynthesis. Vol. 4. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1992. pp. 581–584. [Google Scholar]

- Frank HA, Cua A, Chynwat V, Young A, Gosztola D, Wasielewski MR. The lifetimes and energies of the first excited singlet states of diadinoxanthin and diatoxanthin: the role of these molecules in excess energy dissipation in algae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1277:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(96)00106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank HA, Cua A, Chynwat V, Young A, Gosztola D, Wasielewsky MR. Photophysics of the carotenoids associated with the xanthophyll cycle in photosynthesis. Photosynth Res. 1994;41:389–395. doi: 10.1007/BF02183041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore A, Hazlett TL, Govindjee Xanthophyll cycle dependent quenching of chlorophyll a fluorescence: formation of a quenching complex with a short fluorescence lifetime. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2273–2277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AM. Mechanistic aspects of xanthophyll cycle-dependent photoprotection in higher plant chloroplasts and leaves. Physiol Plant. 1997;99:197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AM, Narendranath M, Yamamoto HY. Epoxidation of zeaxanthin and antheraxanthin reverses non-photochemical quenching of photosystem II chlorophyll a fluorescence in the presence of trans-thylakoid ΔpH. FEBS Lett. 1994;350:271–274. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00784-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss R, Mewes H, Wilhelm C. Stimulation of the diadinoxanthin cycle by UV-B radiation in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Photosynth Res. 1999;59:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Goss R, Richter M, Wild A. Pigment composition of the PS II pigment protein complexes purified by anion exchange chromatography. Identification of xanthophyll binding proteins. J Plant Physiol. 1997;151:115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hager A. Die zusammenhänge zwischen lichtinduzierten xanthophyll-umwandlungen und hill-reaktionen. Ber Deutsch Bot Ges. 1966;79:94–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hager A. Lichtbedingte pH-erniedrigung in einem chloroplastenkompartiment als ursache der enzymatischen violaxanthin-zeaxanthin-umwandlung: beziehungen zur photophosphorylierung. Planta. 1969;89:224–243. doi: 10.1007/BF00385028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager A. Die reversiblen, lichtabhängigen xanthophyllumwandlungen im chloroplasten. Ber Deutsch Bot Ges. 1975;88:27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hager A, Holocher K. Localization of the xanthophyll-cycle enzyme violaxanthin de-epoxidase within the thylakoid lumen and abolition of its mobility by a (light-dependent) pH decrease. Planta. 1994;192:581–589. [Google Scholar]

- Havaux M, Gruszecki WI. Heat and light induced chlorophyll fluorescence changes in potato leaves containing high or low levels of the carotenoid zeaxanthin: indications of a regulatory effect of zeaxanthin on thylakoid membrane fluidity. Photochem Photobiol. 1993;58:607–614. [Google Scholar]

- Havaux M, Niyogi KK. The violaxanthin cycle protects plants from photooxidative damage by more than one mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8762–8767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton P, Ruban AV, Wentworth M. Allosteric regulation of the light-harvesting system of photosystem II. Phil Trans Roy Soc Lond B. 2000;355:1361–1370. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob T, Goss R, Wilhelm C. Unusual pH-dependence of diadinoxanthin de-epoxidase activation causes chlororespiratory induced accumulation of diatoxanthin in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J Plant Physiol. 2001;158:383–390. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey SW, Humphrey GF. New spectrophotometric equations for determining chlorophylls a, b, c1 and c2 in higher plants, algae and natural phytoplankton. Biochem Biophysiol Pflanzen. 1975;167:191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Li X-P, Björkman O, Shih C, Grossman AR, Rosenquist M, Jansson S, Niyogi KK. A pigment-binding protein essential for regulation of photosynthetic light harvesting. Nature. 2000;403:391–395. doi: 10.1038/35000131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr M, Wilhelm C. Algae displaying the diadinoxanthin cycle also possess the violaxanthin cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8784–8789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr M, Wilhelm C. Xanthophyll synthesis in diatoms: quantification of putative intermediates and comparison of pigment conversion kinetics with rate constants derived from a model. Planta. 2001;212:382–391. doi: 10.1007/s004250000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masojidek J, Torzillo G, Koblizek M, Kopecky J, Bernardini P, Sacchi A, Komenda J. Photoadaptation of two members of the chlorophyta (Scenedesmus and Chlorella) in laboratory and outdoor cultures: changes in chlorophyll fluorescence quenching and the xanthophyll cycle. Planta. 1999;209:126–135. doi: 10.1007/s004250050614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell DP, Falk S, Huner NPA. Photosystem II excitation pressure and development of resistance to photoinhibition. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:687–694. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.3.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale P, Sobrino C, Montero O, Lubian LM. Ultraviolet radiation induces xanthophyll de-epoxidation in Nannochloropsis gaditana (abstract no. 35) Phycologia. 2001;40:S-11. [Google Scholar]

- Olaizola M, La Roche J, Kolber Z, Falkowsky PG. Non-photochemical fluorescence quenching and the diadinoxanthin cycle in a marine diatom. Photosynth Res. 1994;41:357–370. doi: 10.1007/BF00019413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olaizola M, Yamamoto HY. Short-term response of the diadinoxanthin cycle and fluorescence yield to high irradiance in Chaetoceros muelleri (Bacillariophyceae) J Phycol. 1994;30:606–612. [Google Scholar]

- Owens TG. Baker NR, Bowyer JR, eds, Photoinhibition of Photosynthesis: From Molecular Mechanisms to the Field. Oxford: Bios Scientific Publishers; 1994. Excitation energy transfer between chlorophylls and carotenoids. A proposed molecular mechanism for non-photochemical quenching; pp. 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Pfündel E, Dilley RA. The pH dependence of violaxanthin deepoxidation in isolated pea chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:65–71. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provasoli L, McLaughlin JJA, Droop MR. The development of artificial media for marine algae. Arch Microbiol. 1957;25:392–428. doi: 10.1007/BF00446694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M, Goss R, Wagner B, Holzwarth AR. Characterization of the fast and slow reversible components of non-photochemical quenching in isolated pea thylakoids by picosecond time-resolved chlorophyll fluorescence analysis. Biochemistry. 1999;38:12718–12726. doi: 10.1021/bi983009a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruban AV, Young AJ, Pascal AA, Horton P. The effects of illumination on the xanthophyll composition of the photosystem II light-harvesting complexes of spinach thylakoid membranes. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:227–234. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siefermann D, Yamamoto HY. Properties of NADPH and oxygen-dependent zeaxanthin epoxidation in isolated chloroplasts. A transmembrane model for the violaxanthin cycle. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1975;171:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(75)90008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stransky H, Hager A. Das carotinoidmuster und die verbreitung des lichtinduzierten xanthophyllzyklus in verschiedenen algenklassen. Arch Microbiol. 1970;73:315–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner B, Goss R, Richter M, Wild A, Holzwarth AR. Picosecond time-resolved study on the nature of high-energy-state quenching in isolated pea thylakoids. Different localization of zeaxanthin dependent and independent mechanisms. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 1996;36:339–350. [Google Scholar]

- Wright SW, Jeffrey SW. High-resolution HPLC system for chlorophylls and carotenoids of marine phytoplankton. In: Jeffrey SW, Mantoura RFC, Wright SW, editors. Phytoplankton Pigments in Oceanography: Guidelines to Modern Methods. Paris: UNESCO Publishing; 1997. pp. 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto HY, Bassi R. Carotenoids: localization and function. In: Ort DR, Yocum CF, editors. Oxygenic Photosynthesis: The Light Reactions. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996. pp. 539–563. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto HY, Nakayama TOM, Chichester CO. Studies of the light interconversions of the leaf xanthophylls. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1962;97:168–173. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(62)90060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Xiang H, Henkow L, Jordan BR, Strid A. The effects of ultraviolet-B radiation on the CFOF1-ATPase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1185:295–302. [Google Scholar]