Abstract

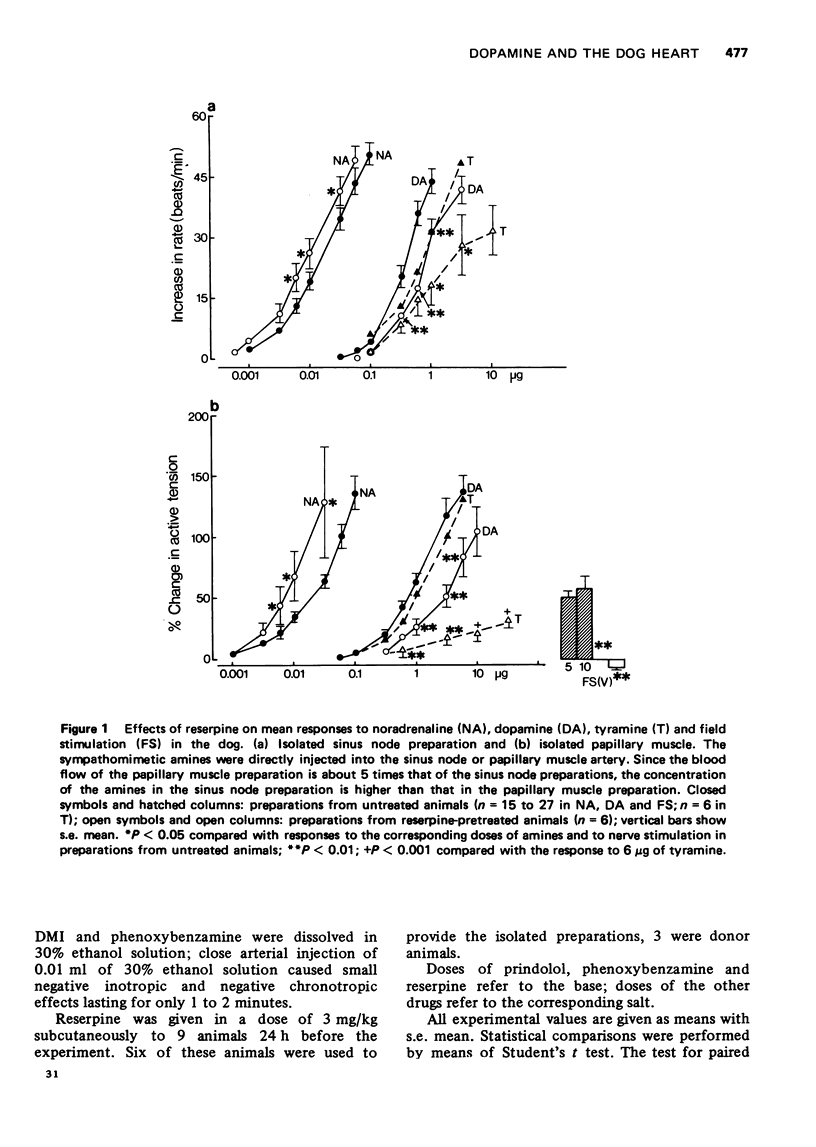

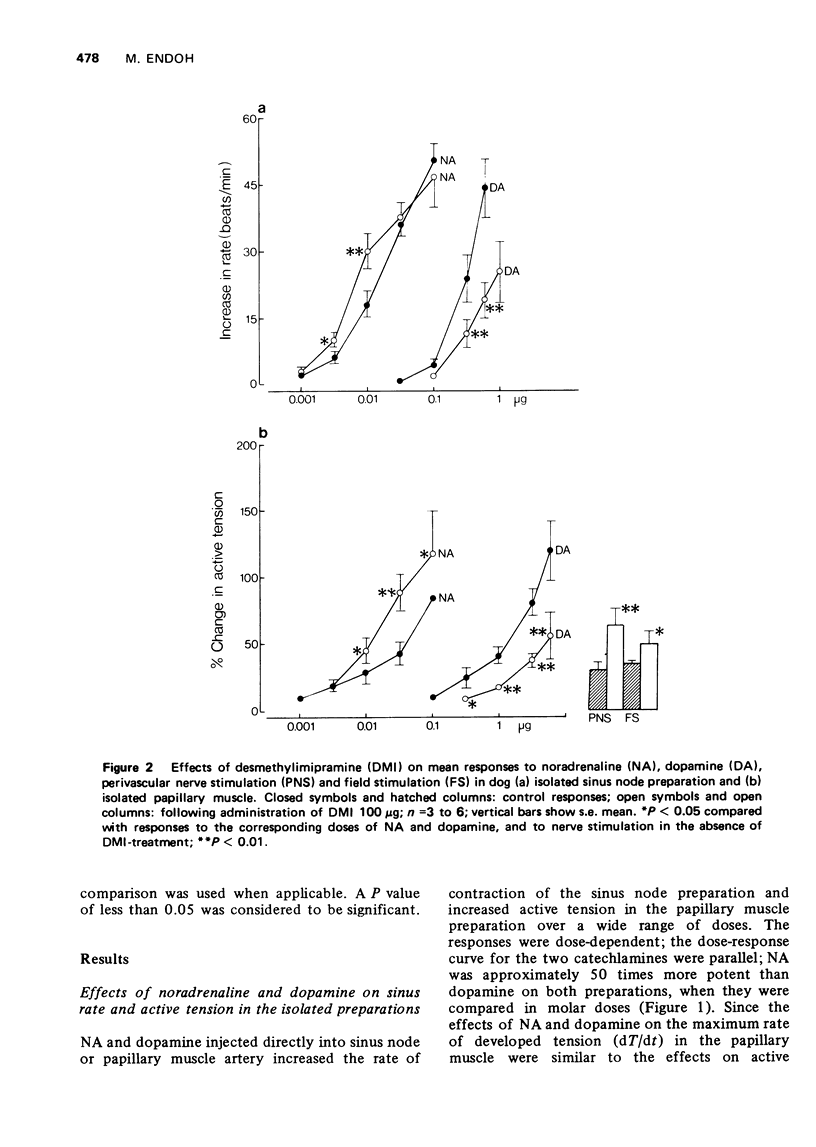

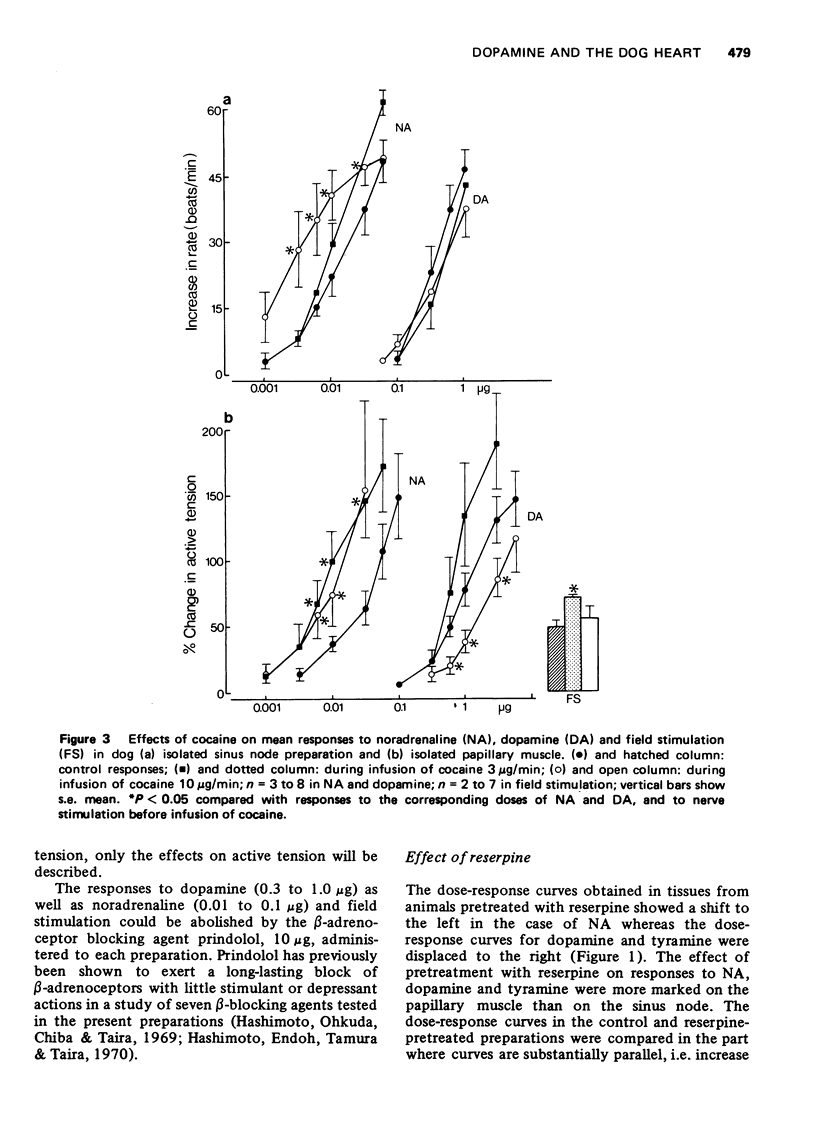

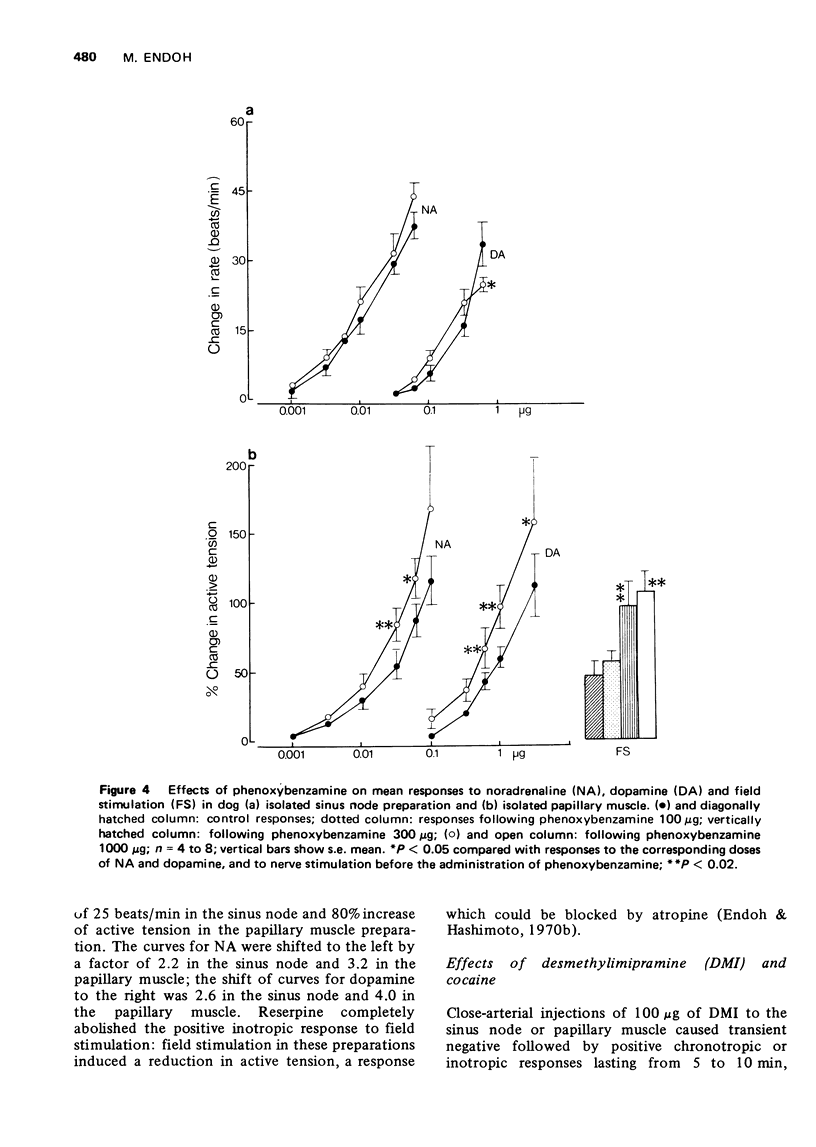

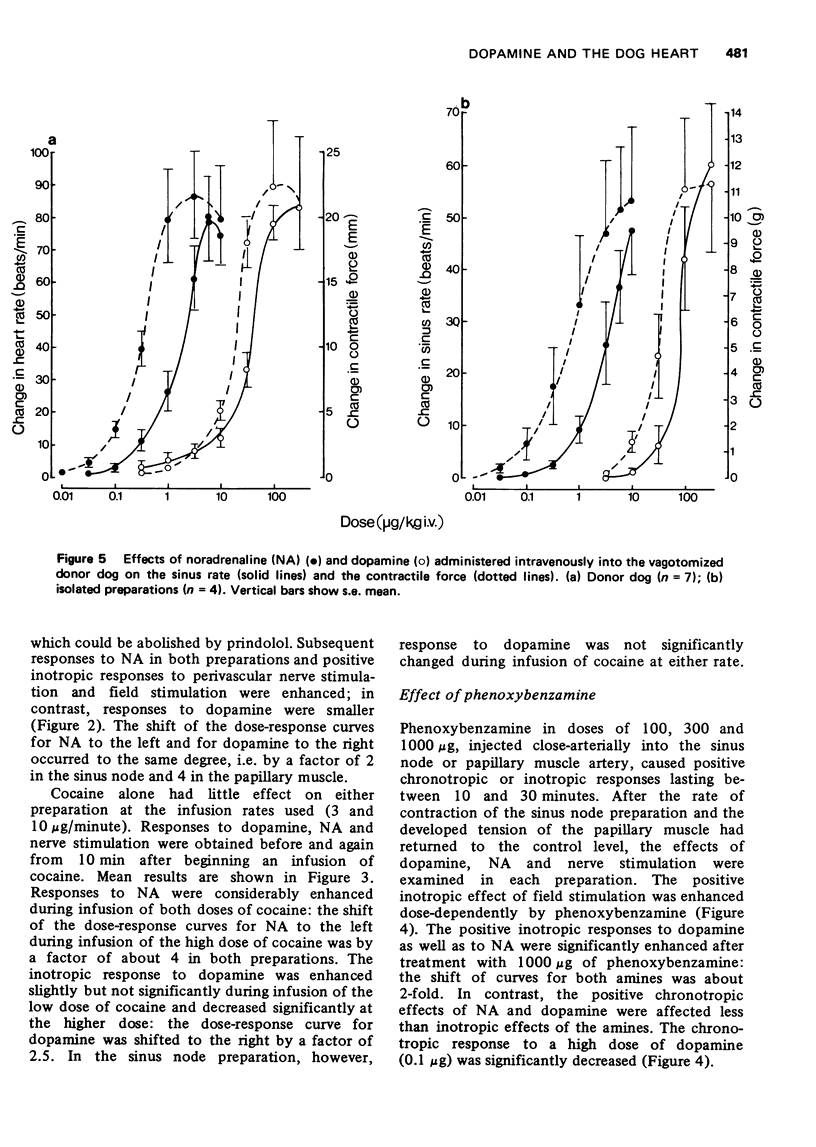

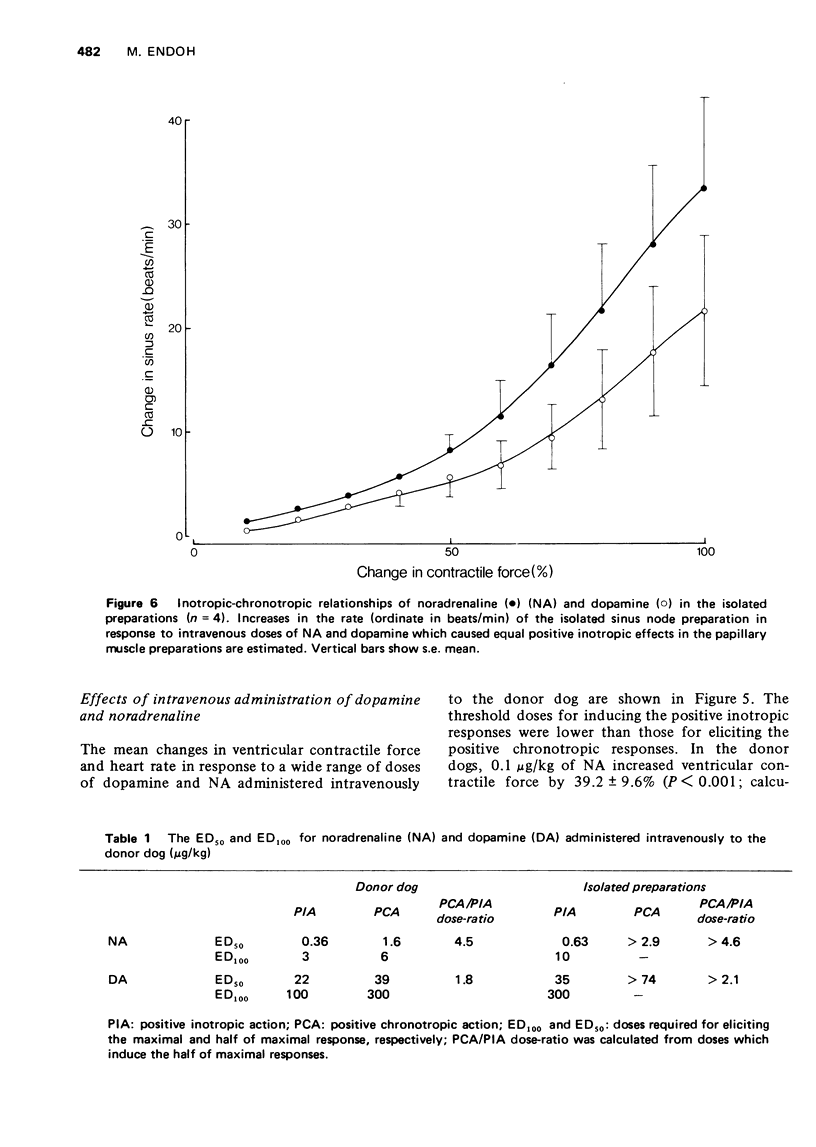

1 Experiments were carried out on dog isolated papillary muscle and sinus node preparations perfused with arterial blood from a donor dog. The chronotropic and inotropic effects of dopamine were analysed by using reserpine, desmethylimipramine (DMI), cocaine and phenoxybenzamine, and the relative chronotropic and inotropic effects defined, the results being compared with those for noradrenaline (NA). 2 The effects of dopamine administered intra-arterially into the isolated preparations were reduced by pretreatment of animals with reserpine both in the papillary muscle and sinus node. The chronotropic effects, however, were affected less by pretreatment with reserpine than were the inotropic effects. 3 Desmethylimipramine (DMI) reduced the inotropic and chronotropic effects of dopamine, and enhanced the effects of NA and nerve stimulation; the chronotropic effects of the amines were less affected than the inotropic effects. 4 Cocaine enhanced considerably the inotropic and chronotropic effects of NA, and decreased the inotropic but not the chronotropic effect of dopamine. 5 Phenoxybenzamine enhanced the inotropic effects of dopamine, NA and nerve stimulation, but did not affect the chronotropic effects of the amines. 6 When dopamine (1 to 300 mug/kg) was administered intravenously to the donor dog, it increased preferentially the contractile force of the ventricular myocardium with a comparatively small change of the sinus rate in the isolated preparations as well as in the heart in vivo. NA (0.1 to 10 mug/kg) caused effects similar to those of dopamine. The maximal inotropic responses to these catecholamines were reached with lower doses than the chronotropic ones. 7 It is concluded that both the positive inotropic and the positive chronotropic responses to dopamine are mediated partially by a direct and partially by an indirect stimulant effect on beta-adrenoceptors in the dog heart. The present results suggest that the difference in activity of dopamine and NA between the ventricular myocardium and the sinus node may be ascribed to the unequal innervation with adrenergic nerve fibres of the atrium and the ventricle (Furnival, Linden & Snow, 1971). The sinus node which is densely innervated by adrenergic nerve fibres may inactivate noradrenaline and dopamine more effectively than the ventricular myocardium through the uptake into the nerve and thereby be less sensitive to the exogenous catecholamines.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ANGELAKOS E. T., FUXE K., TORCHIANA M. L. CHEMICAL AND HISTOCHEMICAL EVALUATION OF THE DISTRIBUTION OF CATECHOLAMINES IN THE RABBIT AND GUINEA PIG HEARTS. Acta Physiol Scand. 1963 Sep-Oct;59:184–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1963.tb02734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEJRABLAYA D., BURN J. H., WALKER J. M. The action of sympathomimetic amines on heart rate in relation to the effect of reserpine. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1958 Dec;13(4):461–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1958.tb00238.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervoni P., Kirpekar S. M., Schwab A. The effect of drugs on uptake and release of catecholamines in the isolated left atrium of the guinea pig. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1966 Feb;151(2):196–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba S., Hashimoto H., Hashimoto K. Comparative study of chronotropic effects of catecholamines and tyramine on the SA node of the dog heart in situ. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1973 Jun;23(3):329–335. doi: 10.1254/jjp.23.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo M., Hashimoto K. Frequency-force relationship in the blood-perfused canine papillary muscle preparation. Jpn J Physiol. 1970 Jun 15;20(3):320–331. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.20.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh M., Hashimoto K., Kimura T. Effects of perivascular nerve stimulation on the contraction and automaticity of the blood-perfused canine papillary muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 1972 Aug;45(4):603–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1972.tb08118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh M., Hashimoto K. Pharmacological evidence of autonomic nerve activities in canine papillary muscle. Am J Physiol. 1970 May;218(5):1459–1463. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.218.5.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh M., Kimura T., Hashimoto K. Comparative study of intropic effects of catecholamines on blood-perfused canine papillary muscle. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1972 Feb;106(2):165–173. doi: 10.1620/tjem.106.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer J. B. Indirect sympathomimetic actions of dopamine. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1966 Apr;18(4):261–262. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1966.tb07866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnival C. M., Linden R. J., Snow H. M. Inotropic changes in the left ventricle: the effect of changes in heart rate, aortic pressure and end-diastolic pressure. J Physiol. 1970 Dec;211(2):359–387. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnival C. M., Linden R. J., Snow H. M. The inotropic and chronotropic effects of catecholamines on the dog heart. J Physiol. 1971 Apr;214(1):15–28. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg L. I. Cardiovascular and renal actions of dopamine: potential clinical applications. Pharmacol Rev. 1972 Mar;24(1):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLMES J. C., FOWLER N. O. Direct cardiac effects of dopamine. Circ Res. 1962 Jan;10:68–72. doi: 10.1161/01.res.10.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORWITZ D., FOX SM 3. D., GOLDBERG L. I. Effects of Dopamine in man. Circ Res. 1962 Feb;10:237–243. doi: 10.1161/01.res.10.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K., Endoh M., Tamura K., Taira N. Comparison of beta-adrenergic blocking activity of DCI, H56-28, ICI50172, LB46, methoxamine, MJ1999 and propranolol in the blood perfused canine papillary muscle preparation. Experientia. 1970;26(7):757–759. doi: 10.1007/BF02232530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K., Kimura T., Kubota K. Study of the therapeutic and toxic effects of ouabain by simultaneous observations on the excised and blood-perfused sinoatrial node and papillary muscle preparations and the in situ heart of dogs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1973 Sep;186(3):463–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K., Ohkuda K., Chiba S., Taira N. Beta-adrenergic blocking effect of dichloroisoprenaline (DCI), (H 56-28, I.C.I. 50172, LB 46), methoxamine (MJ 1999) and propranolol on the sinus node activity of the dog heart. Experientia. 1969 Nov 15;25(11):1156–1157. doi: 10.1007/BF01900247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K., Tanaka S., Hirata M., Chiba S. Responses of the sino-atrial node to change in pressure in the sinus node artery. Circ Res. 1967 Sep;21(3):297–304. doi: 10.1161/01.res.21.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota K., Hashimoto K. Selective stimulation of the parasympathetic preganglionic nerve fibres in the excised and blood-perfused SA node preparation of the dog. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1973;278(2):135–150. doi: 10.1007/BF00500646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE W. C., YOO C. S. MECHANISM OF CARDIAC ACTIVITIES SYMPATHOMIMETIC AMINES ON ISOLATED AURICLES OF RABBITS. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1964 Sep 1;151:93–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAXWELL G. M., ROWE G. G., CASTILLO C. A., CLIFFORD J. E., AFONSO S., CRUMPTON C. W. The effect of dopamine (3-hydroxytyramine), upon the systemic, pulmonary, and cardiac haemodynamics and metabolism of intact dog. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1960 Dec 1;129:62–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUSCHOLL E. [The concentration of noradrenalin and adrenalin in isolated sections of the heart]. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Exp Pathol Pharmakol. 1959;237:350–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuvonen P. J., Westermann E. On the cardiovascular action of dopamine in rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1973;280(4):363–371. doi: 10.1007/BF00506629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHORE P. A., COHN V. H., Jr, HIGHMAN B., MALING H. M. Distribution of norepinephrine in the heart. Nature. 1958 Mar 22;181(4612):848–849. doi: 10.1038/181848a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starke K. Interactions of guanethidine and indirect-acting sympathomimetic amines. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1972 Feb;195(2):309–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRENDELENBURG U. Modification of the effect of tyramine by various agents and procedures. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1961 Oct;134:8–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRENDELENBURG U. The supersensitivity caused by cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1959 Jan;125(1):55–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai T. H., Langer S. Z., Trendelenburg U. Effects of dopamine and alpha-methyl-dopamine on smooth muscle and on the cardiac pacemaker. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1967 May;156(2):310–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]