Abstract

The larval development of the Drosophila melanogaster wings is organized by the protein Wingless, which is secreted by cells adjacent to the dorsal–ventral (DV) boundary. Two signaling processes acting between the second and early third instars and between the mid- and late third instar control the expression of Wingless in these boundary cells. Here, we integrate both signaling processes into a logical multivalued model encompassing four cells, i.e., a boundary and a flanking cell at each side of the boundary. Computer simulations of this model enable a qualitative reproduction of the main wild-type and mutant phenotypes described in the experimental literature. During the first signaling process, Notch becomes activated by the first signaling process in an Apterous-dependent manner. In silico perturbation experiments show that this early activation of Notch is unstable in the absence of Apterous. However, during the second signaling process, the Notch pattern becomes consolidated, and thus independent of Apterous, through activation of the paracrine positive feedback circuit of Wingless. Consequently, we propose that appropriate delays for Apterous inactivation and Wingless induction by Notch are crucial to maintain the wild-type expression at the dorsal–ventral boundary. Finally, another mutant simulation shows that cut expression might be shifted to late larval stages because of a potential interference with the early signaling process.

DEVELOPMENTAL boundaries are established through the juxtaposition of two different cell populations and fulfill two functions during animal development. First, they act as a cell lineage border as demonstrated through the induction of marked clones in Drosophila melanogaster (García-Bellido et al. 1973; Lawrence 1973). Second, they are involved in the generation of morphogen gradients, which guide the growth and patterning of surrounding tissue (Meinhardt 1980, 1983a,b). Examples of borders implementing one or both functions have been found in vertebrates and invertebrates (reviewed by Irvine and Rauskolb 2001).

Drosophila appendages develop from larval structures called imaginal discs. Patterning and growth of the wing imaginal disc are organized by the anterior–posterior and dorsal–ventral boundaries through the morphogens Decapentaplegic and Hedgehog and through the morphogen Wingless (Wg), respectively.

Expression of wg at the dorsal–ventral (DV) boundary depends on two different signaling processes acting at different times during larval development and requiring a cross talk between the Notch (N) and Wg pathways (Figure 1). The first signaling process is triggered at around the second larval instar (48 hr after egg laying, AEL) by the selector gene apterous (ap), which is expressed exclusively in dorsal cells (Diaz-Benjumea and Cohen 1995) (Figure 1a). The expression of ap in dorsal cells induces fringe (fng) and Serrate (Ser) expressions in a cell-autonomous way. Fng prevents the activation of N by Ser in dorsal cells, so that Ser activates N only in ventral cells at the DV boundary (Irvine and Wieschaus 1994; Couso et al. 1995). Active N induces Delta (Dl) only in ventral cells at the DV boundary (Panin et al. 1997) because of the inhibitory effect of Ap on Dl in dorsal cells (Milán and Cohen 2000). Dl requires the presence of Fng to activate N, so that Dl at the ventral side of the DV boundary activates N exclusively in neighboring cells at the dorsal side of the DV boundary (Irvine and Wieschaus 1994; Doherty et al. 1996). Finally, active N upregulates Ser in dorsal cells at the DV boundary, creating a feedback circuit (Panin et al. 1997) (Figure 1b). A formal model of this first signaling process has already been presented elsewhere (González et al. 2006).

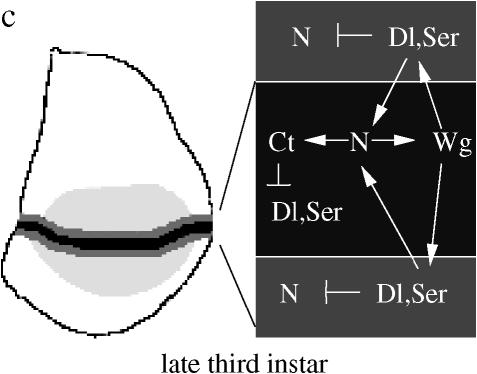

Figure 1.—

Regulatory interactions defining the DV boundary. Juxtaposition of ap expressing and nonexpressing cells at the second larval instar (a) triggers a regulatory network, resulting in the activation of N at the cell boundary during the early third larval instar (b). At late third instar (c), N activation and wg expression are maintained through an intercellular feedback circuit involving two layers of flanking cells on each side of the forming dorsal–ventral boundary.

From the mid-third larval instar (96 hr AEL), the Ap product is progressively inactivated in the dorsal compartment (Milán and Cohen 2000). At this stage, wg expression is triggered in boundary cells by active N. The Wg signal induces the expression of Dl and Ser in flanking cells, i.e., adjacent to boundary cells, and causes its own repression in cells next to the boundary (Rulifson et al. 1996). Dl and Ser from flanking cells maintain N activation in boundary cells in a non-cell-autonomous fashion. Hence, Wg activity is maintained through a paracrine positive feedback circuit between boundary and flanking cells. In boundary cells, the expression of cut (ct) under the control of N inhibits Dl and Ser expression, so that Wg induces Dl and Ser only in flanking cells. On the other hand, the N pathway is repressed in the flanking cells because of high levels of Dl and Ser (de Celis and Bray 1997; Micchelli et al. 1997) (Figure 1c).

Whereas the two signaling processes at the DV boundary are well defined, the precise contribution of each process in the global regulatory network is less understood. In the absence of precise kinetic data, to rigorously establish the global mechanism defining the DV boundary, we delineate here a logical, multilevel model of the epistatic relationships between relevant genes. Qualitative simulations of this model enable the qualitative recovery of the wild-type dynamics, as well as the delineation of abnormal behaviors. The analysis of the abnormal dynamical pathways provides new insight into the core mechanisms at the basis of the wild-type behavior. More specifically, our analysis indicates that the early N signaling process cannot be maintained in the absence of Ap. Consequently, a temporal overlap between the action of the Ap-dependent mechanism and the operation of the Wg paracrine feedback circuit is necessary to reach the wild-type expression pattern.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Model delineation:

Logical variables and functional levels:

Our modeling approach leans on the generalized logical formalism previously developed by R. Thomas and collaborators (Thomas and D'Ari 1990; Thomas et al. 1995). This logical approach is particularly useful to formally integrate disperse experimental data whenever quantitative experimental information is scarce. The mapping from genetic experiments to a logical model is thus intuitive and straightforward. In this logical framework, each product of a regulatory network is modeled as a (Boolean or multilevel) “logical variable.” This approach has been previously applied to the modeling of the segmentation genetic system during early embryonic development (see Sánchez and Thieffry 2003 and references therein). In the present case, our model explicitly encompasses the following regulatory elements: Apterous (Ap), Cut (Ct), Delta (Dl), Fringe (Fng), Notch (N), Serrate (Ser), and Wingless (Wg). The number of values of a given variable is chosen to distinguish the different relevant concentration ranges, at which the corresponding gene product exerts its functions. In the present model, all the elements, excepting Dl and Ser, can take two values, 0 or 1, corresponding to the inactive or active state of the gene. In the case of Dl and Ser, it is well established that low concentrations have a positive non-cell-autonomous effect, whereas high concentrations also exert a negative cell-autonomous effect (de Celis and Bray 1997, 2000; Klein et al. 1997; Sakamoto et al. 2002). Hence, in our model, Dl and Ser can take the values 0, 1, or 2, corresponding to negligible, low, and high product levels. The sets of values associated with the seven regulatory elements in the model are thus: Ap = {0, 1}, Ct = {0, 1}, Dl = {0, 1, 2}, Fng = {0, 1}, N = {0, 1}, Ser = {0, 1, 2}, and Wg = {0, 1}.

Simplifying assumptions:

In our model, the N and Wg pathways have been simplified to a single-step reaction. This simplification does not affect the resulting dynamics, because the absolute reaction delays are implicit during the asynchronous simulation. The assumptions behind the asynchronous simulation are further explained below.

The second simplification regards the various components that have been involved in the restriction of the activation of N and Wg pathways to boundary cells, namely: (i) Dsh (Axelrod et al. 1996), (ii) the Wg signal (Rulifson et al. 1996), (iii) Dl and Ser at high levels (de Celis and Bray 1997; Sakamoto et al. 2002), (iv) nubbin (Neumann and Cohen 1998), (v) lethal(2) giant discs (Klein 2003), (vi) defective proventriculus (Nakagoshi et al. 2002), and (vii) the transmembrane protein Crumbs (Herranz et al. 2006). Here, only the inhibition of N by Dl and Ser at high levels is taken into account, as the explicit inclusion of other mechanisms does not provide new clues in our network analysis.

Multicellular framework:

During the early signaling process, the network dynamics depend on interactions across the DV boundary (Figure 1, a and b). Consequently, the most important features of this first regulatory mechanism can be modeled in terms of two interacting cells, one representing the dorsal layer of boundary cells and the other representing the ventral layer of boundary cells (Figure 4a; González et al. 2006). Since the mid-third larval instar, another signaling mechanism arises, which involves intercellular interactions between boundary cells and their adjacent cells (Figure 1c). To model these interactions, we further consider two additional cells flanking the boundary cells. In total, four cells are thus needed to model the most crucial intercellular interactions involved in the induction of wg expression at the DV boundary of the Drosophila imaginal disc (Figure 2).

Figure 4.—

Simulation of ectopic Ct activity during the first step inactivates N at the boundary. (a) Control simulation of the first step in two boundary cells activates N at the boundary. (b) N activation is perturbed in the presence of ectopic Ct in boundary cells, due to the interference of Ct with Dl and Ser. Inactive genes are shaded. Normal arrows represent positive interactions, whereas blunt arrows represent negative interactions. Notation of regulatory components is described in Figure 3.

Figure 2.—

Model regulatory graph defined with the simulation software GINsim. The pivotal intercellular interactions of this process can be modeled with seven variables in two boundary and two flanking cells, i.e., four cells in total (a). Positive interactions are denoted by normal arrows, negative interactions by blunt arrows, and ambivalent interactions by bullet arrows. Symbols: A, Apterous; C, Cut; D, Delta; F, Fringe; N, Notch; S, Serrate; and W, Wingless. The number (1, 2, 3, or 4) following each symbol indicates whether it corresponds to the dorsal flanking (1, most left), dorsal boundary (2, middle left), ventral boundary (3, middle right), or ventral flanking (4, most right) cell. (b–d) Enlargement of the interactions targeting Dl, N, and Ser in the dorsal flanking cell.

Regulatory interactions:

The activity level of each network element is controlled by the “regulatory interactions” targeting this element. These interactions are each defined by a source component (regulator) and an activity interval. This interval corresponds to the range of the regulator concentrations or activities enabling a regulatory effect on the target (regulated) component. For instance, in the case of N, its incoming interaction, Ser′ → N, is written formally as {Ser′, [1, 2]}. In other words, the interaction of Ser onto N is active whenever Ser′ takes values 1 or 2. The prime (′) denotes a component (here Ser) acting from a neighboring cell.

Values of the logical parameters and underlying evidences:

The temporal evolution of each variable is defined as a function of the active incoming interactions in terms of “logical parameter” values. A specific logical parameter corresponds to each combination of active interactions on a given component. In practice, only nonzero parameters are defined, thus delineating the combinations of active interactions enabling the activation of each component. Logical parameters can take the same values as the corresponding variables. The logical parameters take the form KN({Dl′, 1}, {Fng, 1}) = 1. This notation means that the component (variable) N tends to value 1, whenever both interactions {Dl′, 1} and {Fng, 1} are active, i.e., Dl′ and Fng have the value 1. KN( ) denotes the basal level of N, i.e., its level in the absence of any active incoming interaction.

) denotes the basal level of N, i.e., its level in the absence of any active incoming interaction.

The values of the logical parameters are identical in all cells, with the notable exception of Ap. Below, the list of variables is presented with the corresponding incoming interactions (in boldface type). For the different incoming interactions, the relevant evidences and the logical parameters (followed by an informal description) are presented. For the sake of simplicity, only nonzero parameters in the presence of a single neighboring cell are presented.

Ap (No incoming interactions)

Evidences: Up to the early/mid-third larval instar ap is expressed in dorsal cells (Diaz-Benjumea and Cohen 1993; Williams et al. 1994). Later on, the Ap protein becomes inactivated (Milán and Cohen 1999, 2000).

Parameters: During the early step, KAp(

) = 1 in dorsal cells, and KAp(

) = 1 in dorsal cells, and KAp( ) = 0 in ventral cells. By contrast, KAp(

) = 0 in ventral cells. By contrast, KAp( ) = 0 in both dorsal and ventral cells during the second signaling process.

) = 0 in both dorsal and ventral cells during the second signaling process.Ct N → Ct: {N, 1}

Evidences: Inactivation of the N pathway leads to the reduction of ct and wg expressions. Conversely, ectopic activation of N induces ct and wg (Diaz-Benjumea and Cohen 1995; de Celis et al. 1996; Doherty et al. 1996; Neumann and Cohen 1996; de Celis and Bray 1997, 2000; Micchelli et al. 1997; Brennan et al. 1999).

Parameters: KCt({N, 1}) = 1. That is, active N induces Ct.

Dl Ap ⊣ Dl: {Ap, 1}

Evidences: Dl is cell-autonomously repressed in dorsal cells due to the Ap activity (Milán and Cohen 2000).

Parameters: The presence of active Ap leads only to (implicit) null parameters of Dl. That is, Ap inactivates Dl.

Ct ⊣ Dl: {Ct, 1}:

Evidences: In ct− discs, Dl and Ser do not refine to flanking cells (de Celis and Bray 1997).

Parameters: The presence of active Ct leads only to (implicit) null parameters of Dl. That is, Ct inactivates Dl.

N → Dl: {N, 1}

Evidences: Dl expression is lost non-cell autonomously in ap− and Ser− mutants. Ectopic induction of the N pathway induces cell autonomously Dl (de Celis and Bray 1997; Panin et al. 1997; Klein and Martínez-Arias 1998; Klein et al. 2000).

Parameters: KDl({N, 1}) = 1. That is, active N induces low levels (value 1) of Dl.

Wg′ → Dl: {Wg′, 1}

Evidences: Ectopic Wg non-cell autonomously induces Dl and Ser (Micchelli et al. 1997).

Parameters: KDl({Wg′, 1}) = KDl({N, 1}, {Wg′, 1}) = 2. That is, Wg activates Dl in neighboring cells at high levels (value 2) as is usually assumed during the late larval stages.

Fng Ap → Fng: {Ap, 1}

Evidences: The expression pattern of fng matches that of ap. In ap− mutants, fng is not expressed. On the other hand, ap expression is not affected in fng− mutants (Irvine and Wieschaus 1994).

Parameters: KFng({Ap, 1}) = 1. That is, Ap activates Fng.

N Dl′ → N: {Dl′, 1},

Fng → N: {Fng, 1}

Evidences: Ectopic expression of Dl in the presence but not in the absence of Fng in the signal-receiving cells induces ectopic margins non-cell autonomously (Kim et al. 1995; de Celis et al. 1996; Doherty et al. 1996; de Celis and Bray 1997, 2000; Klein et al. 1997; Panin et al. 1997; Klein and Martínez-Arias 1998; Brückner et al. 2000).

Parameters: KN({Dl′, 1}, {Fng, 1}) = KN({Dl′, 1}, {Fng, 1}, {Ser′, [1, 2]}) = 1. That is, Dl at low levels (value 1) requires Fng to activate N. The interaction from Ser′ to N, i.e., {Ser′, [1, 2]}, present in the second parameter is described below.

Ser′ → N: {Ser′, [1, 2]}

Evidences: Ectopic expression of Ser in the absence but not in the presence of Fng in the signal-receiving cells induces non-cell-autonomously ectopic margins (Irvine and Wieschaus 1994; Speicher et al. 1994; Kim et al. 1995; de Celis and Bray 1997; Fleming et al. 1997; Klein et al. 1997; Panin et al. 1997; Klein and Martínez-Arias 1998).

Parameters: KN({Ser′, [1, 2]}) = KN({Dl′, 1}, {Ser′, [1, 2]}) = 1. That is, Ser at both low and high levels (values 1 and 2) requires the absence of Fng to activate N.

Dl′ → N: {Dl′, 2},

Ser′ → N: {Ser′, [1, 2]}

Evidences: Ser and Dl are expressed at high levels in two stripes of cells flanking the boundary in late third larval instar. Dl−Ser− double clones but not single clones lead to the loss of ct and wg expressions. Conversely, ectopic expressions of Ser or Dl induce N-dependent genes in dorsal and ventral compartments (de Celis and Bray 1997; Micchelli et al. 1997).

Parameters: KN({Dl′, 2}) = KN({Dl′, 2}, {Fng, 1}) = KN({Dl′, 2}, {Ser′, [1, 2]}) = KN({Dl′, 2}, {Fng, 1}, {Ser′, [1, 2]}) = 1. That is, Dl at high levels (value 2) and Ser at both low and high levels (values 1 and 2) redundantly activate N in neighboring cells.

Dl ⊣ N: {Dl, 2},

Ser ⊣ N: {Ser, 2}

Evidences: Mutant cells overexpressing Dl and Ser repress Ct and Wg in the boundary, when the mutant cells cross the boundary. This repression can be titrated by coexpression of N (de Celis and Bray 1997, 2000; Klein et al. 1997; Sakamoto et al. 2002).

Parameters: These interactions lead to (implicit) null parameters. That is, Dl and Ser at high levels (value 2) redundantly inactivate N.

Ser Ap → Ser: {Ap, 1}

Evidences: ap and Ser expressions coincide in dorsal cells. Whereas Ser is perturbed in ap− mutants, ap expression is not affected in Ser− mutants (Couso et al. 1995; Yan et al. 2004).

Parameters: KSer({Ap, 1}) = 1. That is, Ap activates Ser.

Ct ⊣ Ser: {Ct, 1}

Evidences: Confer the description of the interaction: Ct ⊣ Dl.

Parameters: This interaction leads only to (implicit) null parameters. That is, Ct inactivates Ser.

N → Ser: {N, 1}

Evidences: Ectopic expression of activated N or of the N pathway transducer Su(h) induces Ser in a wg-independent way (de Celis and Bray 1997; Panin et al. 1997; Klein and Martínez-Arias 1998; Klein et al. 2000; Yan et al. 2004).

Parameters: KSer({Ap, 1}, {N, 1}) = 1. That is, N in dorsal cells (in the presence of Ap) activates Ser.

Wg′ → Ser: {Wg′, 1}

Evidences: Confer the description of the interaction Wg′ → Dl.

Parameters: KSer({Wg′, 1}) = KSer({Ap, 1}, {Wg′, 1}) = KSer({N, 1}, {Wg′1}) = KSer({Ap, 1}, {N, 1}, {Wg′, 1}) = 2. That is, Wg activates Ser in neighboring cells at high levels (value 2) as is usually assumed during the late larval stages.

Wg N → Wg: {N, 1}

Evidences: Confer the description of the interaction: N → Ct.

Parameters: KWg({N, 1}) = 1. That is, active N induces Wg.

Simulation:

State transition graph:

The result of a simulation is represented in terms of an oriented graph, where each node corresponds to a state, and each arc corresponds to a transition from one state to another. A state of the system is defined by the values of the logical variables associated with the network elements (Chaouiya et al. 2003). In this graph, the terminal nodes correspond to stable states. More complex graph structures can be associated with other dynamical properties, including cyclic attractors. Figure 3 summarizes the main dynamical trajectories in the (asynchronous) state transition graph corresponding to our model.

Figure 3.—

Main dynamical trajectories of the model. From an initial state with asymmetrical Ap expression (state st1), the simulation of the first signaling step leads to a single stable state (st2), where Ap, Fng, and Ser are active in dorsal cells, Dl is active in the ventral boundary cell, and N is active in both boundary cells, in agreement with the experimental observations (cf. Figure 1b). State st2 is then used as initial state for the simulation of the second step, which leads to the experimentally observed stable state st3a, where N, Ct, and Wg are active in boundary cells, and Dl and Ser are active in flanking cells at high levels (cf. Figure 1c). The other, abnormal stable states found (states st3b–st3e) provide further insight into the actual network mechanism (see text). Notation: “a” stands for Ap = 1, “c” for Ct = 1, “d1” for Dl = 1, “d2” for Dl = 2, “f” for Fng = 1, “n” for N = 1, “s1” for Ser = 1, “s2” for Ser = 2, and “w” for Wg = 1.

Asynchronous assumption:

At a given state, two or more variables might be called to increase or decrease their values, depending on relevant parameter values. However, genetic experiments do not usually provide quantitative kinetic information. Therefore, the order at which the variables switch their values cannot be rigorously defined. Nevertheless, under the asynchronous assumption, the simulation generates all possible switching orders. For instance, if it has been shown that Ap induces fng and Ser expressions, genetic experiments do not tell us which of them first reaches a functional activity level. Under the asynchronous assumption, both transitions are generated, i.e., with either Fng or Ser switching its value. More generally, this asynchronous approach encompasses all possible dynamic pathways compatible with one given regulatory graph and one logical parameter configuration. This feature perfectly allows us to model genetic interactions without any knowledge about the reaction kinetics.

Simulation software:

To ease the definition of logical regulatory graphs and parameters, as well as the simulations of such logical models for different initial states, our group has developed a software called GINsim (Chaouiya et al. 2003; González et al. 2006). Logical models and simulation results are stored in a specific graph-based XML format called GINML. A GINML file containing the model presented in this article is provided in the supplemental data at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/. This file can be opened, edited, and simulated with GINsim, which can be freely downloaded by academics from our website (http://gin.univ-mrs.fr/GINsim). GINsim further supports the simulation of various types of perturbations (e.g., loss-of-function mutants, ectopic gene expression, etc.).

In parallel, we use GNU Prolog to solve the systems of logical equations underlying the regulatory graphs. Indeed, standard constraint programming techniques can be applied to solve such discrete systems (Devloo et al. 2003). A specific plug-in will be soon provided in the public release of GINsim to ease the export of logical models into GNU prolog. Finally, we also provide a piecewise linear equation transposition of our model stored into the SBML format (level 2, version 1) as supplemental data at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/.

RESULTS

Simulations of wild-type and known mutations:

To gain insight into each signaling process, the model is simulated in two steps, where only the genes involved at each step are explicitly considered. The other genes are blocked to zero (Figure 3). GINsim provides an easy way to block regulatory element values without redefining the model or parameter values (González et al. 2006). After the simulation of the wild-type model, simulations of known mutations are presented (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Stable states of the simulations of known mutants

| Dorsal

|

Ventral

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic background | Flanking | Boundary | Flanking | In silico phenotype | |

| Wild type | d2, s2 | c, n, w | c, n, w | d2, s2 | |

| — | — | — | — | ||

| c, n, w | d2, s2 | c, n, w | d2, s2 | ||

| d2, s2 | c, n, w | d2, s2 | c, n, w | ||

| c, n, w | d2, s2 | d2, s2 | c, n, w | ||

| 1. N− dorsal clone | — | — | — | — | Mutant |

| — | — | d2, s2 | c, n, w | ||

| — | d2, s2 | c, n, w | d2, s2 | ||

| 2. wg− disc | — | — | — | — | Mutant |

| 3. ct− disc | — | — | — | — | Mutant |

| d1, n, w | d2, s2 | d1, n, w | d2, s2 | ||

| d2, s2 | d1, n, w | d2, s2 | d1, n, w | ||

| d1, n, w | d2, s2 | d2, s2 | d1, n, w | ||

| 4. Dl−Ser− flanking clone | — | — | — | — | Mutant |

| — | c, n, w | d2, s2 | c, n, w | ||

| c, n, w | d2, s2 | d2, s2 | c, n, w | ||

| c, n, w | d2, s2 | c, n, w | d2, s2 | ||

| 5. Dl− dorsal clone | s2 | c, n, w | c, n, w | d2, s2 | Wild type |

| — | — | — | — | ||

| c, n, w | s2 | c, n, w | d2, s2 | ||

| s2 | c, n, w | d2, s2 | c, n, w | ||

| c, n, w | s2 | d2, s2 | c, n, w | ||

| 6. Ser− dorsal clone | d2 | c, n, w | c, n, w | d2, s2 | Wild type |

| — | — | — | — | ||

| c, n, w | d2, | c, n, w | d2, s2 | ||

| d2 | c, n, w | d2, s2 | c, n, w | ||

| c, n, w | d2 | d2, s2 | c, n, w | ||

| 7. Dl−Ser− dorsal clone | — | — | — | — | Mutant |

| — | — | c, n, w | d2, s2 | ||

| — | c, n, w | d2, s2 | c, n, w | ||

Simulations of known mutants (most left side) lead to mutant phenotypes (most right side) except in the case of single Dl− or Ser− clones. A mutant phenotype in the simulation is assessed through the presence or not of the wild-type stable state (underlined). In the middle of the table, the stable states (with active genes) reached by each mutant simulation are shown. These in silico phenotypes agree with experimental observations (see text). Gene notation is described in Figure 3.

First step—Apterous-dependent activation of N:

The simulation of this step has already been presented in the context of a two-cell model (González et al. 2006). Here, we revisit this process using our novel four-cell model as a basis to study later larval stages. During this step, the basal Ap parameter (showing the basal expression of Ap) is set to 1 [KAp( ) = 1] in dorsal and to 0 [KAp(

) = 1] in dorsal and to 0 [KAp( ) = 0] in ventral cells (see materials and methods). At this stage, Ct and Wg are not yet explicitly taken into account, as they are supposed to act only after the early third larval instar. Therefore, Ct and Wg variables are blocked to 0.

) = 0] in ventral cells (see materials and methods). At this stage, Ct and Wg are not yet explicitly taken into account, as they are supposed to act only after the early third larval instar. Therefore, Ct and Wg variables are blocked to 0.

This simulation leads to a stable state where Fng and Ser are present in both dorsal cells, Dl in the ventral boundary cell, and N in both boundary cells (state st2 in Figure 3). This simulation is thus coherent with the available data on the early signaling process (Figure 1b).

Second step—establishment of the paracrine Wg positive feedback circuit:

To simulate this signaling process, the basal Ap parameter is switched to 0 in the dorsal cells [KAp( ) = 0], reproducing the inactivation of Ap protein at mid-third larval instar (Milán and Cohen 2000). Conversely, Ct and Wg are now explicitly taken into account in the simulation.

) = 0], reproducing the inactivation of Ap protein at mid-third larval instar (Milán and Cohen 2000). Conversely, Ct and Wg are now explicitly taken into account in the simulation.

Simulation of this step leads to a stable state, where Ct, N, and Wg are active in boundary cells, and Dl and Ser are active in flanking cells at high levels (state st3a in Figure 3). This simulation thus agrees with experimental observations regarding the late signaling process (Figure 1c).

In addition to the wild-type dynamics, this regulatory network has the inherent capacity to generate other nonobserved stable states (states st3b to st3e in Figure 3). The “trivial” stable state (st3b in Figure 3) implies the inactivation of the whole regulatory network and corresponds experimentally to the complete loss of gene expression in boundary and flanking cells. The origin of this in silico phenotype is discussed later in the context of a mutant simulation (Figure 5).

Figure 5.—

The early signaling process cannot stably maintain the boundary after Ap inactivation. In the simulation of a double-mutant disc for ct−wg− induced at the second instar stage, the network is activated normally during the first step (st1–st2). However, the early regulatory interactions become inactivated during the second step (st2–st3b). The notation of regulatory components is described in the Figure 3 legend.

The other nonobserved stable states (st3c, st3d, and st3e in Figure 3) arise from symmetries of the intercellular regulatory network. The stable states st3c and st3d correspond to phenotypes with alternating flanking-like and boundary-like cell fates, specified by the expression of Dl and Ser at high levels in either one or the other boundary cell. Along the trajectories leading to these abnormal stable states, Wg from one boundary cell induces Dl and Ser at high levels in the other boundary cell, further leading to the downregulation of the N signal in that cell. In vivo, this situation is prevented through the appropriate induction of Ct, which inhibits cell autonomously Dl and Ser (de Celis and Bray 1997).

Simulations of experimentally observed mutations:

Our model can be further validated through the simulation of known loss-of-function mutations or ectopic gene expression experiments. Mutant simulations are performed through the blockage of the expression of a gene at a given level, e.g., at level 0 to simulate a loss-of-function mutation.

Simulation of mutations involved in the first step:

We have presented the results of the simulations of early perturbations elsewhere (González et al. 2006). These simulations encompass the behavior of different perturbed clones: Dl−, fng−, and Ser− mutant clones touching the boundary in the dorsal or ventral compartments, as well as a clone ectopically expressing fng, leading to mutant phenotypes consistent with published data, in particular in the case of ventral Dl− (Doherty et al. 1996), dorsal fng− (Irvine and Wieschaus 1994), dorsal Ser− clones (Couso et al. 1995), and ectopic fng clones (Kim et al. 1995). These results have been reproduced with the present (four cells) logical model, leading to the coherent, qualitative counterparts of all relevant reported patterns.

Simulation of mutations involved in the second step:

The stable states for loss-of-function or ectopic mutant clones affecting the second signaling process have been computed using constraint programming (see materials and methods). Table 1 gives the stable states for each perturbation considered.

In the simulation of a N− clone in the dorsal (flanking and boundary) cells, the wild-type stable state is lost (mutant 1 in Table 1), in agreement with the margin nicks observed in N− clones abutting the wing margin (de Celis and García-Bellido 1994; Micchelli et al. 1997).

wg− mutant discs and large clones reaching the boundary produce notches of the wing margin (Couso et al. 1994). Simulation of this genotype also results in a mutant phenotype (mutant 2 in Table 1).

Simulation of a ct− mutant disc does not lead to the wild-type stable state, but rather to an ectopic upregulation of the N ligands in boundary cells (mutant 3 in Table 1). This agrees with observations in ct− mutant discs, where there are margin nicks in the wing and ectopic upregulation of the N ligands in boundary cells (de Celis and Bray 1997; Micchelli et al. 1997). This in silico experiment highlights the function of Ct to repress Dl and Ser in the boundary cells, leading to a shift of their expression toward the flanking cells.

Fixing the values of Dl and Ser to value 0 simulates flanking cells unable to receive the Wg signal and results in a mutant phenotype (mutant 4 in Table 1). In the corresponding experiment, clones unable to receive the Wg signal in flanking cells cause cell-autonomous ectopic upregulation of N signaling (Micchelli et al. 1997). This experiment underlines the role of Wg in the activation of the late inhibiting function of Dl and Ser onto N signaling.

Whereas in silico single mutants for either Dl or Ser in the dorsal cells preserve the wild-type trajectory (mutants 5 and 6 in Table 1), simulation of a double Dl−Ser− dorsal clone hinders the wild-type stable state (mutant 7 in Table 1). Altogether, the single- and double-mutant simulations of Dl and Ser show their functional redundancy at late larval stages, in agreement with the experimental results reported by Micchelli et al. (1997). To model the redundant activation of N by Dl and Ser, Dl at high levels has to be independent of Fng. This contrasts with low Dl levels, which require the presence of Fng.

In conclusion, the simulation of mutant clones involved in the second signaling step agrees with the experimental phenotypes reported in the literature.

Ct might perturb the early signaling process:

Although Wg and Ct are similarly induced by N, there are notable differences in the expression timing of these genes. Whereas the expression of Wg is observed since the early third larval instar (Couso et al. 1995), Ct is not expressed until the late third larval instar (de Celis and Bray 1997; Micchelli et al. 1997). Furthermore, thermosensitive N fly alleles raised at different temperatures suggest a higher threshold of N to induce ct expression (Herranz et al. 2006). These observations emphasize a constraint shifting ct expression toward late larval stages.

To clarify the impact of this late expression, we modify the timing of Ct activity and impose its ectopic expression during the first signaling process. A first-step simulation is performed, where the value of Ct is blocked to 1. This in silico mutation leads to the loss of N in boundary cells (Figure 4b). The reason for this phenotype is that during the early signaling process, Dl and Ser are required in boundary cells to activate N (see control in Figure 4a). Precocious Ct represses autonomously Dl and Ser activity, and so active N is lost in boundary cells.

The repression of Dl and Ser by Ct has been demonstrated through genetic experiments (de Celis and Bray 1997), which do not discriminate between direct and indirect interactions. Here for the sake of computational simplicity, we have assumed that Ct directly inhibits Dl and Ser. Under this assumption, we conclude that ct expression in vivo has evolved to late larval stages to avoid a possible interference of Ct with the early signaling process.

Coupling between the early and late signaling processes:

The analysis of abnormal dynamical trajectories gives insight about the actual network mechanism. For example, the stable state st3b (Figure 3), which implies the complete inactivation of the system, coincides with the unique stable state reached by the wg− mutant simulation (mutant 2 in Table 1), so that state st3b could arise from a delayed Wg activation. Alternatively, state st3b could arise from the precocious activation of Ct, which also leads to the complete inactivation of the boundary (Figure 4b). These hypotheses could be distinguished through the simultaneous inactivation of ct and wg during the second signaling process.

To simulate a double loss-of-function ct−wg− mutant, we block the values of Ct and Wg to value 0 during the second step. In this mutant simulation, the network is normally activated during the first step (st1 to st2 in Figure 5). However, after inactivation of Ap during the second step, the boundary is inactivated as in the wg− mutant simulation (st2 to st3b in Figure 5).

This simulation shows that the paracrine Wg feedback circuit constitutes the true differentiation switch, since the first signaling process fades out in the absence of Ap. Hence, the trajectory of the system toward state st3b in the wild-type simulation (Figure 3) arises from the precocious inactivation of the first signaling process prior to the induction of the Wg feedback circuit. We conclude that the overlapping of the first signaling process and the Wg feedback circuit is thus essential to stabilize the DV boundary at late larval stages.

DISCUSSION

Logical model of the network at the DV boundary:

In this work, we have presented a formal model of the regulatory network controlling wingless (wg) expression in DV boundary cells. Dispersed experimental observations have been integrated and formalized into a multivalued logical model encompassing four cells and seven genes in each cell (Figure 2), including the cross talk between Notch (N) and Wg pathways.

We have simulated this model in two steps that correspond to the two successive signaling processes involved. The stable states reached by the wild-type simulation agree with experimental observations (states st2 and st3a in Figure 3). Simulations of known mutants also validate our model (Table 1; González et al. 2006).

Moreover, novel mutants have been presented, whose phenotypes, specially in the case of double mutants, are difficult to predict intuitively (Figures 4 and 5). A further application of this model consists of simulating mutant clones at specific locations of the disc. This presents an advantage over the experimental generation of mutant clones, which appear in random positions.

The early signaling process requires continuous Ap input:

It has been proposed that the activation of N could be maintained by an intercellular feedback circuit across boundary cells involving interactions from dorsal Ser to ventral N, from ventral N to Dl, from ventral Dl to dorsal N, and finally from dorsal N to Ser (state st2 of Figure 5).

From a formal point of view, a positive feedback circuit is considered functional if it constitutes a switch, i.e., if it can maintain a stable activity configuration initiated by a transient signal after the disappearance of this signal. In the case of the early signaling process, as shown in the ct−wg− simulation (Figure 5), the positive circuit mentioned above does not enable the maintenance of the early asymmetric final state (state st2 of Figure 5) independently of Ap activity. This contradicts some current understanding of this process (Panin et al. 1997; Yan et al. 2004).

The proposal of the early feedback circuit relies largely on the observation that active N is able to induce its ligands Dl and Ser (Panin et al. 1997). However, the induction of Dl and Ser is compartment dependent; i.e., N induces Dl and Ser mainly in ventral and dorsal cells, respectively. As the compartment differences are set by Ap, the interactions of this hypothetical feedback circuit cannot be considered independently from Ap input. Our statement is supported by experimental data, where removal of the interaction from N to Ser, thus interrupting the feedback circuit, does not cause a mutant phenotype (Yan et al. 2004). In conclusion, specific experiments as well as our simulation results suggest that the early signaling process (state st2 in Figure 3) cannot be sustained in the absence of Ap.

Coupling of the early and late signaling processes:

After Ap inactivation, the paracrine Wg positive feedback circuit takes over the maintenance of N activation. A proper transition between the two mechanisms imposes constraints on their temporal deployment. Indeed, according to our simulations, a precocious inactivation of Ap in the course of the early signaling process leads to an inactive stable state (state st3b in Figure 3).

A significant temporal overlap between the two mechanisms in vivo ensures a proper coupling between them. Whereas Ap protein is active up to the mid-third larval instar (Milán and Cohen 2000), Wg activity is already induced by N in boundary cells at least since the early third larval instar (Couso et al. 1995).

Symmetries of the paracrine feedback circuit of N and Wg:

The key component of the late signaling process is the paracrine positive feedback circuit of N and Wg mediated by Dl and Ser in flanking cells. In contrast to the earlier feedback circuit, this late feedback circuit can be considered functional, as it enables the maintenance of the differentiated N pattern, independently of the state of the initial input.

In principle, this feedback circuit can be switched in various symmetric ways (states st3a, st3c, st3d, and st3e in Figure 3). The selection of the trajectory leading to the wild-type stable state (st3a) depends on uncharacterized kinetic aspects of concurrent (in)activation processes (not explicitly considered here).

Gene activation order in the DV boundary:

Our current understanding of the inhibiting role of Ct onto Dl and Ser is based on genetic experiments (de Celis and Bray 1997). These experiments do not allow the discrimination between direct (i.e., through repression of the Dl and Ser promoters) and indirect (i.e., through repression of the Wg pathway, which induces Dl and Ser expression) regulatory effects. For the sake of computation simplicity, in our model, we have assumed a direct repression of Dl and Ser by Ct. Under this assumption, we provide a verifiable explanation for the late expression of Ct (Figure 4).

Gene activation order at the DV boundary:

Our data thus support the following gene activation order at the DV boundary. Ap in dorsal cells first defines the DV boundary through the unstable activation of N. Low levels of active N immediately induce the Wg paracrine feedback circuit. This feedback circuit stabilizes the DV boundary at early third larval stage, well before the Ap-dependent process is downregulated at mid-third larval stage. Once the system becomes definitely independent of the Ap-dependent process, Ct is induced by high levels of active N in boundary cells to exert its function, late enough to preclude any interference with the initial setting of the DV boundary.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Sánchez for his precious advice regarding the delineation of this model. We also thank A. Naldi for his active participation in the development of GINsim and S. Kerridge for his critical reading of an earlier version of this manuscript. We further acknowledge financial support from the French Research Ministry through the Action Concertée Incitative IMPbio program.

References

- Axelrod, J. D., K. Matsuno, S. Artavanis-Tsakonas and N. Perrimon, 1996. Interaction between Wingless and Notch signaling pathways mediated by dishevelled. Science 271: 1826–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, K., T. Klein, E. Wilder and A. Martínez-Arias, 1999. Wingless modulates the effects of dominant negative notch molecules in the developing wing of Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 216: 210–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brückner, K., L. Pérez, H. Clausen and S. Cohen, 2000. Glycosyltransferase activity of Fringe modulates Notch-Delta interactions. Nature 406: 411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaouiya, C., E. Remy, B. Mossé and D. Thieffry, 2003. Qualitative analysis of regulatory graphs: a computational tool based on a discrete formal framework. Lect. Notes Control Inf. Sci. 294: 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Couso, J., E. Knust and A. Martínez-Arias, 1995. Serrate and wingless cooperate to induce vestigial gene expression and wing formation in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 5: 1437–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couso, J. P., S. A. Bishop and A. Martínez-Arias, 1994. The wingless signalling pathway and the patterning of the wing margin in Drosophila. Development 120: 621–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Celis, J. F., and S. Bray, 1997. Feed-back mechanisms affecting Notch activation at the dorsoventral boundary in the Drosophila wing. Development 124: 3241–3251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Celis, J. F., and S. J. Bray, 2000. The Abruptex domain of Notch regulates negative interactions between Notch, its ligands and Fringe. Development 127: 1291–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Celis, J. F., and A.G arcía-Bellido, 1994. Roles of the Notch gene in Drosophila wing morphogenesis. Mech. Dev. 46: 109–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Celis, J. F., A. García-Bellido and S. J. Bray, 1996. Activation and function of Notch at the dorsal-ventral boundary of the wing imaginal disc. Development 122: 359–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devloo, V., P. Hansen and M. Labbe, 2003. Identification of all steady states in large networks by logical analysis. Bull. Math. Biol. 65: 1025–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Benjumea, F. J., and S. M. Cohen, 1993. Interaction between dorsal and ventral cells in the imaginal disc directs wing development in Drosophila. Cell 75: 741–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Benjumea, F. J., and S. M. Cohen, 1995. Serrate signals through Notch to establish a Wingless-dependent organizer at the dorsal/ventral compartment boundary of the Drosophila wing. Development 121: 4215–4225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, D., G. Feger, S. Younger-Shepherd, L. Y. Jan and Y. N. Jan, 1996. Delta is a ventral to dorsal signal complementary to Serrate, another Notch ligand, in Drosophila wing formation. Genes Dev. 10: 421–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, R. J., Y. Gu and N. A. Hukriede, 1997. Serrate-mediated activation of Notch is specifically blocked by the product of the gene fringe in the dorsal compartment of the Drosophila wing imaginal disc. Development 124: 2973–2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Bellido, A., P. Ripoll and G. Morata, 1973. Developmental compartmentalisation of the wing disk of Drosophila. Nat. New Biol. 245: 251–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González, A., A. Naldi, L. Sánchez, D. Thieffry and C. Chaouiya, 2006. GINsim: A software suite for the qualitative modelling, simulation and analysis of regulatory networks. Biosystems 84: 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herranz, H., E. Stamataki, F. Feiguin and M. Milán, 2006. Self-refinement of notch activity through the transmembrane protein crumbs: modulation of gamma-secretase activity. EMBO Rep. 7: 297–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, K. D., and C. Rauskolb, 2001. Boundaries in development: formation and function. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 17: 189–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, K. D., and E. Wieschaus, 1994. Fringe, a boundary-specific signaling molecule, mediates interactions between dorsal and ventral cells during Drosophila wing development. Cell 79: 595–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., K. D. Irvine and S. B. Carroll, 1995. Cell recognition, signal induction, and symmetrical gene activation at the dorsal-ventral boundary of the developing Drosophila wing. Cell 82: 795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, T., 2003. The tumour suppressor gene l(2)giant discs is required to restrict the activity of Notch to the dorsoventral boundary during Drosophila wing development. Dev. Biol. 255: 313–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, T., and A. Martínez-Arias, 1998. Interactions among Delta, Serrate and Fringe modulate Notch activity during Drosophila wing development. Development 125: 2951–2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, T., K. Brennan and A. Martínez-Arias, 1997. An intrinsic dominant negative activity of serrate that is modulated during wing development in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 189: 123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, T., L. Seugnet, M. Haenlin and A. Martínez-Arias, 2000. Two different activities of Suppressor of Hairless during wing development in Drosophila. Development 127: 3553–3566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, P., 1973. A clonal analysis of segment development in Oncopeltus (Hemiptera). J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 30: 681–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt, H., 1980. Cooperation of compartments for the generation of positional information. Z. Naturforsch. C 35: 1086–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt, H., 1983. a A boundary model for pattern formation in vertebrate limbs. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 76: 115–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt, H., 1983. b Cell determination boundaries as organizing regions for secondary embryonic fields. Dev. Biol. 96: 375–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micchelli, C. A., E. J. Rulifson and S. S. Blair, 1997. The function and regulation of cut expression on the wing margin of Drosophila: Notch, Wingless and a dominant negative role for Delta and Serrate. Development 124: 1485–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milán, M., and S. M. Cohen, 1999. Regulation of LIM homeodomain activity in vivo: a tetramer of dLDB and apterous confers activity and capacity for regulation by dLMO. Mol. Cell 4: 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milán, M., and S. M. Cohen, 2000. Temporal regulation of apterous activity during development of the Drosophila wing. Development 127: 3069–3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagoshi, H., T. Shirai, Y. Nabeshima and F. Matsuzaki, 2002. Refinement of wingless expression by a wingless- and notch-responsive homeodomain protein, defective proventriculus. Dev. Biol. 249: 44–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, C. J., and S. M. Cohen, 1996. A hierarchy of cross-regulation involving Notch, wingless, vestigial and cut organizes the dorsal/ventral axis of the Drosophila wing. Development 122: 3477–3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, C. J., and S. M. Cohen, 1998. Boundary formation in Drosophila wing: Notch activity attenuated by the POU protein Nubbin. Science 281: 409–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panin, V. M., V. Papayannopoulos, R. Wilson and K. D. Irvine, 1997. Fringe modulates Notch-ligand interactions. Nature 387: 908–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rulifson, E. J., C. A. Micchelli, J. D. Axelrod, N. Perrimon and S. S. Blair, 1996. Wingless refines its own expression domain on the Drosophila wing margin. Nature 384: 72–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, K., O. Ohara, M. Takagi, S. Takeda and K. Katsube, 2002. Intracellular cell-autonomous association of Notch and its ligands: a novel mechanism of Notch signal modification. Dev. Biol. 241: 313–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, L., and D. Thieffry, 2003. Segmenting the fly embryo: a logical analysis of the pair-rule cross-regulatory module. J. Theor. Biol. 224: 517–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speicher, S. A., U. Thomas, U. Hinz and E. Knust, 1994. The Serrate locus of Drosophila and its role in morphogenesis of the wing imaginal discs: control of cell proliferation. Development 120: 535–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R., and R. D'Ari, 1990. Biological Feedback. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- Thomas, R., D. Thieffry and M. Kaufman, 1995. Dynamical behaviour of biological regulatory networks–I. Biological role of feedback loops and practical use of the concept of the loop-characteristic state. Bull. Math. Biol. 57: 247–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J. A., S. W. Paddock, K. Vorwerk and S. B. Carroll, 1994. Organization of wing formation and induction of a wing-patterning gene at the dorsal/ventral compartment boundary. Nature 368: 299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S. J., Y. Gu, W. X. Li and R.J. Fleming, 2004. Multiple signaling pathways and a selector protein sequentially regulate Drosophila wing development. Development 131: 285–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]