Abstract

A screen for modifiers of Dpp adult phenotypes led to the identification of the Drosophila homolog of the Sno oncogene (dSno). The dSno locus is large, transcriptionally complex and contains a recent retrotransposon insertion that may be essential for dSno function, an intriguing possibility from the perspective of developmental evolution. dSno is highly transcribed in the embryonic central nervous system and transcripts are most abundant in third instar larvae. dSno mutant larvae have proliferation defects in the optic lobe of the brain very similar to those seen in baboon (Activin type I receptor) and dSmad2 mutants. This suggests that dSno is a mediator of Baboon signaling. dSno binds to Medea and Medea/dSno complexes have enhanced affinity for dSmad2. Alternatively, Medea/dSno complexes have reduced affinity for Mad such that, in the presence of dSno, Dpp signaling is antagonized. We propose that dSno functions as a switch in optic lobe development, shunting Medea from the Dpp pathway to the Activin pathway to ensure proper proliferation. Pathway switching in target cells is a previously unreported mechanism for regulating TGFβ signaling and a novel function for Sno/Ski family proteins.

THE oncogene v-ski was originally identified in an avian Sloan-Kettering virus via its ability to transform chick embryo fibroblasts (Li et al. 1986). Sno (a ski-related novel gene) shares significant amino acid identity with Ski, and Sno overexpression also causes transformation (Boyer et al. 1993). In transfected mammalian cells Sno and Ski can form multimeric complexes and act as components of a histone deacetylase complex that represses transcription (Nomura et al. 1999). Sno is present in a single copy in the human genome but multiple promoters and alternative splicing generate six distinct Sno transcripts in humans (Nomura et al. 1989). Four isoforms of the Sno protein have been identified with the longest isoform known as SnoN (Pearson-White and Crittenden 1997).

Numerous studies in mammalian cells have shown that SnoN antagonizes signal transduction pathways downstream of TGFβ/Activin proteins. In brief, TGFβ/Activin signal transduction involves the activation of Smad2, the formation of Smad2/Smad4 complexes, and the translocation of the complex into the nucleus where it stimulates transcription (Massagué et al. 2005). Cell culture studies show that, in the absence of TGFβ/Activin proteins, Sno physically interacts with Smad2 and Smad4, repressing their transcriptional ability. Alternatively, when TGFβ/Activin ligands are present, Sno is rapidly ubiquitinated and degraded, permitting these Smads to activate target gene expression, including the transcription of Sno. This subsequent round of Sno expression leads to renewed interactions with Smads and to the attenuation of Smad-mediated gene expression (Luo et al. 1999; Stroschein et al. 1999). However, two studies suggest that Sno's role in signaling is more complex (da Graca et al. 2004; Sarker et al. 2005).

Sno's function in development is also uncertain. Two studies of independently derived Sno knockout mice reached different conclusions for unknown reasons. One study shows early embryonic lethality (preimplantation, day E3.5) for homozygous mutant embryos (Shinagawa et al. 2000). The second study reports that homozygous mutants are viable and that these mice have a defect in T-cell activation (Pearson-White et al. 2003).

Here we report the characterization of the Drosophila melanogaster homolog of Sno (dSno). In Drosophila, as in vertebrates, two TGFβ subfamilies are present. The bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) subfamily member Dpp signals through its type I receptor Thickveins to its dedicated transducer Mad (Smad1 homolog) and the Co-Smad Medea (Smad4 homolog). The TGFβ/Activin subfamily member activin signals through its type I receptor Baboon to its dedicated transducer dSmad2 and Medea (Newfeld and Wisotzkey 2006). We found that dSno binds Medea and then functions as a mediator of Activin signaling by enhancing the affinity of Medea for dSmad2. We show that antagonism for BMP signaling likely arises as a secondary consequence of dSno overexpression. Our examination of dSno loss-of-function mutants shows that dSno is required in cells of the optic lobe of the brain to maintain proper rates of cell proliferation. Given that Dpp signaling is essential for neuronal differentiation in the optic lobe (Yoshida et al. 2005), our data suggest that dSno functions as a switch that shunts Medea from the Dpp pathway to the Activin pathway to ensure a proper balance between differentiation and proliferation in the brain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular biology:

Primers that flank the predicted gene CG7233 (5′dSno 5′-TGGCGAAAATGGATAACTGA-3′ and 3′dSno 5′-GAGGAGGGTGTAGCAATAAT-3′) were utilized. Then Spe (5′-end) and Sph (3′-end) were exploited to clone CG7233 into pGEM (Promega, Madison, WI). pGem.dSno was sequenced and then utilized to screen the LD and LP cDNA libraries from BDGP (http://www.fruitfly.org/about/materials/cDNA-list.html). cDNAs were sequenced and mapped to the genomic scaffold by BLAST. Northerns were conducted as described (Newfeld and Gelbart 1995). Mapping of deletion breakpoints was conducted by serially probing a quantitative Southern blot of genomic DNA from dSnosh1402, dSnoEX4B, dSnoEX17B, and Df(2L)BSC41 (all balanced over CyO). Probes corresponded to CG7233 (155099–153862), the dSnoA 3′ exon (137578–136801), dSnoN 3′ exon (75588–74859), and the most 5′ exon associated with dSno (163048-162922). UAS.dSno was generated from a Spe fragment of pGem.dSno ligated into the Xba sites of pUAST. Inverse PCR on dSnosh1402 and Df(2L)BSC41 was conducted as described (http://www.fruitfly.org/about/methods/inverse.pcr.html).

Drosophila genetics:

Strains deleted for the 28D-E region—Df(2L)XE-3801, Df(2L)BSC41, Df(2L)XE-2750, Df(2L)Trf-C6R31, Df(2L)TE29Aa-11, and Df(2L)Excel7034—are as described in FlyBase (2006). l(2)sh1402 is as described in Oh et al. (2003). babo32, babo52, and dSmad2mb388 are as described in Zheng et al. (2003). UAS.dSno transgenic lines, l(2)sh1402 excision lines, complementation tests between CG7231 mutants and l(2)sh1402, a recombination test of the P-element insertion in l(2)sh1402, stage of lethality tests for dSno mutants, and rescue of dSno mutants with heat-shock-induced expression of UAS.dSno were conducted by standard methods (e.g., Nicholls and Gelbart 1998).

For the recombination test, we generated females with an unbalanced l(2)sh1402 chromosome (chromosome II). The P-element insertion in this strain is marked with mini-white, so from these females we collected 110 male progeny bearing a mini-white-marked chromosome balanced over CyO and 110 male progeny bearing a chromosome without the mini-white marker balanced over CyO. These males were individually mated to females with the visible marker In(2LR)Gla on their second chromosome balanced over CyO. From each single male cross, male and female progeny containing the l(2)sh1402-derived chromosome over CyO were collected. These flies were sibmated and for each sibmate the deviation from the expected Mendelian ratio of CyO to non-CyO progeny was calculated.

For complementation tests, females with the l(2)sh1402 chromosome balanced over CyO were mated to males with the P{wHy}CG7231 or the P{EPgy2}EY11884 or the P{SUPor-P}CG7231[KG04307] chromosome over CyO (FlyBase 2006). At least 100 progeny were counted for each cross and deviation from the expected Mendelian ratio of CyO to non-CyO progeny was calculated.

For stage of lethality tests on embryos, we collected eggs for 2 hr from cages containing either CyO-balanced stocks of dSno mutant lines or crosses between two different CyO-balanced dSno mutant lines. A total of 100 eggs were transferred to a gridded grape plate and examined 24 hr later. The number of unhatched eggs was noted. For stage of lethality tests on larvae and pupae, we collected embryos as above, placed 200 eggs on a gridded grape plate, and then transferred the eggs and grape grid to a culture bottle with media. The number of pupae cases and eclosed adults were tallied over a 19-day period. Larval lethality was estimated by subtracting the number of unhatched eggs (determined above), uneclosed pupae, and eclosed adults from 200 (the number of eggs). Each test was repeated three times and fine-scale determinations (e.g., first instar vs. third instar larval lethality) were based on direct observation. Results were normalized to remove the influence of the CyO balancer by comparing dSno mutant data to results from control tests of a wild-type chromosome (obtained from an OregonR stock) balanced over CyO.

For heat-shock Gal4/UAS.dSno-mediated rescue of dSno mutants, we generated strains homozygous for either Hsp70.Gal4 (Brand and Perrimon 1993) or UAS.dSno on chromosome III and each dSno mutant balanced over CyO. Eggs collected as above were heat-shocked in all possible combinations of 10 hr, 3 days and 4 days after egg laying (e.g., at 10 hr only; at 10 hr and at 3 days, etc.). Heat shocks were administered in a 37° water bath for 70 min either by floating the grape plate or by utilizing a culture vial with the cotton forced down below the water level. Stage of lethality was evaluated as above with the following additional controls: no heat shock (cultures maintained at 25°) for all genotypes and all heat-shock regimes applied to each Hsp70.Gal4 or UAS.dSno parental strain alone. Each rescue experiment was repeated three times and the phenotype of the eclosed adults was determined by the presence or absence of CyO. Deviation from the expected Mendelian ratio of CyO to non-CyO progeny was then calculated.

For UAS.dSno, we utilized dSnoI protein-coding sequences (equal to CG7233) because genetic analyses indicated that dSnoI is capable of performing all roles necessary for viability. Gal4 and UAS lines are as described (Marquez et al. 2001) except UAS.Mad1 is described in Takaesu et al. (2005), UAS.CA-Tkv, and Hsp-70.Gal4 are described in Newfeld et al. (1997). Gal4/UAS genotypes were generated using two independent UAS transgenic lines. For coexpression genotypes, females homozygous for A9.Gal4 (on the X chromosome) and UAS.Mad, UAS.Med, or UAS.dSmad2 (on chromosome III) were crossed to males homozygous for UAS.dSno.

Bioinformatics:

To identify similar sequences, to map dSno cDNAs, and to examine the species distribution of the 297TE, we utilized BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST and http://www.flybase.org/blast). Sno-related sequences were aligned in Clustal-X (Thompson et al. 1997). The total length of the alignment is 1370 amino acids. The neighbor-joining method was utilized in MEGA3 to generate an unrooted phylogeny and to estimate the statistical significance of individual branch points via bootstrap resampling (Kumar et al. 2004). Coiled-coil motifs were identified using Coils 2.2 (Lupas 1996).

RNA in situ and immunohistochemistry:

RNA in situ hybridization to embryos and third instar imaginal disks with dpp or dSno cDNAs were conducted as described (Takaesu et al. 2002). Double labeling of embryos with dSno and lacZ riboprobes was utilized to identify dSnosh1402 homozygous mutant embryos. Staining of pupal imaginal disks with a monoclonal antibody recognizing dSRF was conducted as described (Takaesu et al. 2005). Larval brains together with eye imaginal disks were dissected and fixed in PBS containing 3.7% formaldehyde for 1 hr at room temperature, followed by three washes for 10 min in PBS plus 0.1% triton X-100 (PBT). Tissue was incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4° followed by four 10-min washes in PBT. Secondary antibodies were incubated for 2–4 hr followed by four 10-min washes in PBT. Brains and disks where mounted in 80% glycerol/20% PBT. The rat anti-Elav (7E8A10), mouse anti-chaoptin (24B10), and mouse anti-Robo (13C9) antibodies were obtained from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank and used at 1/400, 1/1000, and 1/50 dilutions, respectively. Rabbit antiphosphorylated histone H3 (pSer10, H-0412, Sigma, St. Louis) antibody was used at 1/400 dilution. Secondary anti-mouse rabbit and rat antibodies linked to AlexaFlour 568 or FITC (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) were used at 1/300 dilution.

Co-immunoprecipitation:

T7-tagged dSmad2 and Mad are as previously described (Hyman et al. 2003). dSnoI and Medea coding sequences were transferred by PCR into pCMV5 with either Flag or T7 epitope tags. We utilized the dSnoI isoform because genetic studies indicate that it can perform all roles necessary for viability and for consistency with our wing assays. Flag-tagged dSmad2 and Mad were generated by transferring the coding sequence from pCMV-T7 to pCMV5-Flag. COS-1 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and transfected in 60-mm dishes using LipofectAmine (Invitrogen, San Diego). COS-1 cells were lysed by sonication in MSHD (100 mm NaCl, 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.8, 10% glycerol, 1% NP 40) or PBS with 1% NP 40, supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Following centrifugation, lysates were precleared with protein A Sepharose and complexes were precipitated on Flag agarose (Sigma). After washing, proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-P (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Blots were incubated with anti-Flag M2 (Sigma) or anti-T7 (Novagen) antibodies and horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse second layer (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Proteins were visualized with ECL (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK). For direct Western blots, a portion of cleared lysate was subject to SDS–PAGE and blotting as above.

RESULTS

Four dSno proteins and the highly conserved Sno/CORL/Dachsund family:

We previously reported a screen for modifiers of dpp adult mutant phenotypes that identified lilliputian, a new component of the Dpp-signaling pathway (Su et al. 2001). A second mutant generated in that screen, E(dpp)46.3, has a chromosomal inversion breakpoint in the same cytological region (28D) as CG7233. CG7233 is a predicted intronless open reading frame of 338 amino acids that is referred to as SnoN in FlyBase (2006). Unfortunately, E(dpp)46.3 was lost some years ago, but the coincidence intrigued us. In addition, CG7233 is missing the second half of mammalian SnoN. We were curious about the true nature of Drosophila SnoN and wondered if it played any role in Dpp signaling during development.

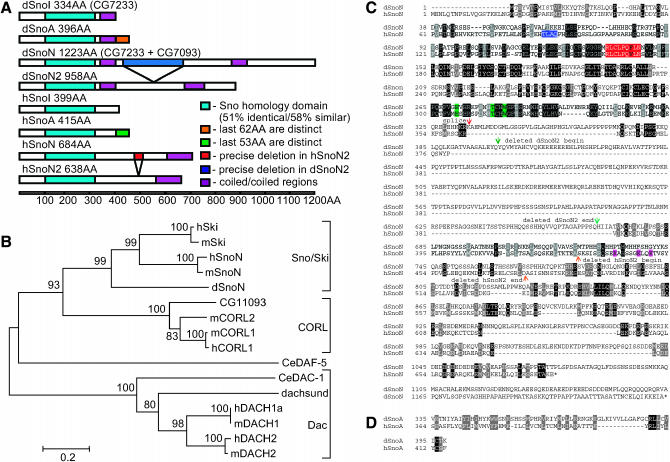

We began by screening cDNA libraries with CG7233 and identified 17 clones (15 from a pupal library and 2 from an embryonic library). After eliminating duplicates, we were left with 12 distinct cDNAs. They ranged in size from 4.1 to 7.2 kb and most included the adjacent but 70-kb distant gene prediction CG7093. While it was clear that several cDNAs were not full length, they could nevertheless be sorted into six distinct classes. From these it was determined that four protein isoforms were encoded (Figure 1A) and that these corresponded to the four human Sno proteins: SnoA, SnoI, SnoN, and SnoN2 (Pearson-White and Crittenden 1997). Like their mammalian counterparts, dSno proteins share a common N-terminal region (the Sno homology domain) and have distinct C termini. Further, each C terminus has motifs such as coiled-coils that are conserved in both species.

Figure 1.—

Four dSno proteins and the Sno/CORL/Dachsund family. (A) Four Sno protein isoforms (SnoI, SnoA, SnoN, and SnoN2) from Drosophila and humans. The name and size of each isoform as well as the presence of CG7233 and CG7093 is indicated. Colored boxes represent significant features as indicated and the scale bar indicates amino acid length. (B) Phylogenetic tree of the Sno/CORL/Dachsund family. The tree is unrooted and branch lengths are drawn to scale. The scale bar shows the number of amino acid substitutions per site between two sequences. Statistically significant bootstrap values (>75) are shown (Sitnikova 1996). The GenInfo Identifier numbers are hCORL1-73476377, hDACH1a-18375611, hDACH2-16876441, hSKI-4506967, hSnoN-36510, mCORL1-27369603, mCORL2-51771047, mDACH1-6681129, mDACH2-15809024, mSKI-21322226, mSnoN-68067873, DmDACH- 24584623, DmCG11093-24638746, CeDAF-5-17532717, and CeDAC-1-71980877. (C) Alignment of hSnoN and dSnoN. Within dSnoN, CG7233 is present as amino acids 1–334 and CG7093 is 337–1223. CG7233 corresponds to dSnoI. Amino acids in both species were shaded if the residue is identical (black) or similar (gray). Colored amino acids have the following definitions: dark blue, Smad2/3 interaction; green, Smad4 interaction; red, destruction box/APC recognition; purple, ubiquitinated lysines. The splice junction connecting CG7233 to CG7093 in dSnoN is indicated with an orange arrow. The last four amino acids of CG7233 are replaced by an alanine and a glutamic acid immediately upstream of the methionine in CG7093. dSnoN has two coiled-coil domains (308–344 and 839–902) and hSnoN has one (520–684). The 47 amino acids in hSnoN between the light-brown arrows are replaced by a single asparagine in hSnoN2. The 265 amino acids in dSnoN between the green arrowheads are absent in dSnoN2. (D) Alignment of the C termini of hSnoA (GI no. is 36508) and dSnoA. The splice to the 3′ exon in dSnoA occurs at the same site as the splice in dSnoN.

We then identified 15 sequences from humans, mice, flies, and worms with significant sequence similarity to the longest dSno isoform, dSnoN. A phylogenetic analysis (Figure 1B) of this multigene family revealed the presence of three major subfamilies (Sno/Ski, CORL, and Dachsund). This tree has considerable statistical support and is topologically similar to those of other TGFβ pathway components (e.g., receptors and Smads; Newfeld et al. 1999). In all subfamilies, vertebrate and invertebrate genes cluster together, suggesting that they are homologs descended from a common ancestor like Dpp and BMP2/BMP4.

The Dachsund (Dac) subfamily appears to be the oldest as it is found in worms, flies, and mammals. These are Dach1 and Dach2 in mammals, Dac in D. melanogaster, and Dac-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans (Hammond et al. 1998). Within a 66-amino-acid region near their N termini (referred to as the Dac-box or DS domain) human Dach1 and SnoN show 29% identity. In transfected mammalian cells, human Dach1 was shown to antagonize TGFβ/Activin signaling (Wu et al. 2003). In Drosophila, interaction between Dac and TGFβ family members is indirect: during eye development Dpp activates dac expression via the Eyes absent protein (Curtiss and Mlodzik 2000). C. elegans Dac-1 was recently identified in a screen for genes affecting DNA stability (Pothof et al. 2003) and has not been connected to TGFβ signaling.

Note that Daf-5, which does not belong to any subfamily, is not the C. elegans Ski homolog as previously reported (da Graca et al. 2004). Our analysis shows that Daf-5 has equal similarity to both the CORL and Sno/Ski subfamilies and may approximate their common ancestor. The CORL subfamily is not present in C. elegans and to date only CORL1 has been studied (Mizuhara et al. 2005). Within a stretch of 161 amino acids (completely encompassing the Dac box) mouse CORL1 and SnoN have 34% identity. CORL1 functions as a corepressor for a homeodomain protein in neurons but has not been linked to TGFβ signaling.

The Sno/Ski subfamily is also absent from C. elegans and alignments of dSnoN with hSno and hSki (not shown) indicate that dSnoN and hSnoN are more similar. Thus Ski is the newest member of this subfamily and is unique to mammals. Alignment of SnoN isoforms from human and fly (Figure 1C) shows significant homology in a region near the N terminus that is common to all Sno proteins in both species. This Sno homology domain is part of the CG7233 prediction and falls between amino acids 92 and 296 in dSnoN. Within this domain there are a number of conserved features. These include the Dac box (dSnoN 138-201), CORL domain (dSnoN 119-270), the nine-amino-acid destruction box/APC recognition site, and the three amino acids that interact with Smad4 (Wu et al. 2002). One difference between the species is that dSnoN is missing the Smad2/3 interaction domain found in hSnoN. Downstream of this region is the splice to CG7093 and the rest of the protein corresponds to that predicted gene.

In the central domain of the protein, dSnoN is missing the ubiquitinated lysines important in the regulation of hSnoN activity (Stroschein et al. 2001). Interestingly, these lysines are also missing in hSnoN2 (the internally deleted form of SnoN). In both cases, it is possible that other lysines are targeted for ubiquitination. A 164-amino-acid stretch at the C terminus of hSnoN and hSnoN2 forms a coiled-coil domain that is important for dimerization (Wu et al. 2002). In dSnoN, there are two coiled-coil domains that together contain 99 residues separated by 495 amino acids. The first domain is present in all dSno isoforms but the second is seen only in dSnoN and dSnoN2. In dSnoN2 the distance between the domains is 230 amino acids. An alignment of the distinct 3′-ends of hSnoA and dSnoA (Figure 1D) shows this region is roughly similar in size (52 vs. 62 amino acids) and moderately conserved (31% amino acid similarity). The most highly conserved region is the C-terminal 9 amino acids that are 33% identical and 66% similar.

Overall, proteins of the Sno/CORL/Dachsund family show substantial evolutionary conservation: the Sno homology domain is easily discernible across species while fly and human Sno have the same number of structurally similar isoforms.

dSno locus is large and transcriptionally complex and includes a retrotransposon:

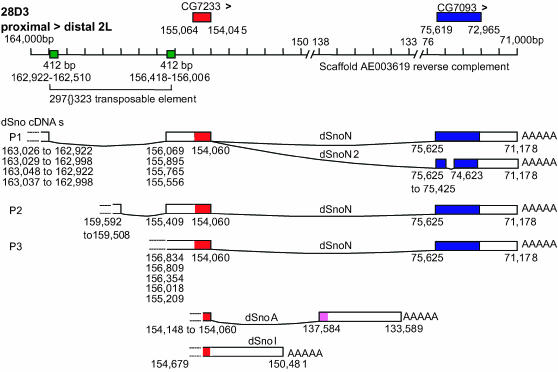

Sequencing the 12 distinct dSno cDNAs (9 encode SnoN and 1 each encoding dSnoA, dSnoI, and dSnoN2) and mapping their 5′- and 3′-ends to genomic sequence by BLAST revealed that the minimum size of the dSno locus is 92 kb (Figure 2). In addition to the alternative 3′ exons that create four dSno isoforms, our cDNA sequences suggest three discrete promoters that together account for six classes of dSno transcripts.

Figure 2.—

The dSno locus is large and transcriptionally complex and includes a retrotransposon. The intron/exon structure of dSno is shown. The coordinate line represents 93 kb of genomic sequence from the 28D3 cytological region. The centromere is to the left. Individual tick marks represent 1 kb and the line is broken in two places to represent the entire interval. Above the line, nucleotide numbers from the genome sequence scaffold AE003619 are shown. dSno transcription runs opposite to the numbering of AE003619 and, as a result, nucleotide numbers decline from the dSno promoter region to its poly(A) tail. The location of CG7233 (red boxes) and CG7093 (blue boxes) and their orientations (arrowheads) are shown. A 297 family transposon is shown with its 412-bp direct repeats (green boxes). cDNAs that span the 297 element and begin at a potential 5′ promoter (P1) contained four variations of the exon 1/2 splice junction. Variation in cDNA 5′-ends that begin within or immediately downstream of the 297 element at a presumed 3′ promoter (P3) are shown. It is also possible that the exon inside the 297TE that we believe initiates at a proposed promoter 2 is an alternative exon for transcripts that begin at our potential promoter 1. C-terminal alternative splices that generate the SnoN2 (an internal deletion) or SnoA proteins are shown. All splice junctions conform to the consensus 5′ AG{G_exon_AG}GT 3′ except the internal deletion creating dSnoN2 where the 5′ G of the exon is replaced by a C. The C-terminal extension of the SnoA open reading frame is also shown (pink box). Dashed lines indicate that there is uncertainty about whether the cDNA is full length and that the promoters for dSnoA and dSnoI are unknown. The intron between the coding exons is 78.5 kb in dSnoN and 16.5 kb in dSnoA.

Unexpectedly, the dSno locus contains an insertion of a 297 family transposable element (long-terminal-repeat-bearing retrotransposon; Kaminker et al. 2002) in the midst of the putative promoter region. As a result, the 297 transposable element (297TE) is predicted to have a significant effect on dSno transcription. Further, a genetic analysis of dSno, described below, suggests that deletion of the 297TE is lethal.

One cDNA sequence suggests that a possible dSno promoter (promoter 2) sits inside of the 297TE element. This cDNA splices around the downstream 412-bp terminal repeat to an exon that contains the dSno initiator methionine. Four cDNAs span the 297TE and begin at the most 5′ dSno exon and potentially represent transcripts initiating at promoter 1. Each of these contains distinct variations in their exon 1/2 splice junction. Two splice acceptor sites are utilized: one is 76 bp upstream of the 297TE and the other is adjacent to the 297TE terminal repeat. There are four splice donor sites: one is inside the 297TE direct repeat and three are downstream. All splice junctions joining exons 1 and 2 for cDNAs beginning at our putative promoter 1 and promoter 2 conform to the consensus. Five cDNAs begin within or immediately downstream of the 297TE element, suggesting the presence of a third promoter (promoter 3). Two of these begin within the 297TE and contain the 412-bp repeat, two begin within the 412-bp repeat, and one begins downstream of the 297TE. All five of these cDNAs read directly through to the dSno initiator methionine in exon 1.

dSno overexpression antagonizes BMP signaling:

Studies in mammalian cells showed that, when overexpressed, Sno is an antagonist of TGFβ/Activin signaling (e.g., Luo et al. 1999). However, dSno came to our attention via a screen for Dpp modifiers, so we wondered if overexpression of dSno antagonizes Dpp signaling.

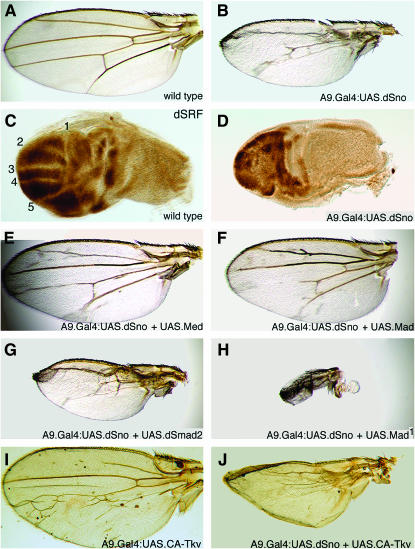

Overexpression of dSno with A9.Gal4 (throughout the presumptive wing blade) resulted in small wings with multiple vein truncations (Figure 3B) at 100% penetrance. We then examined A9.Gal4:UAS.dSno pupal wing disks for Drosophila serum response factor (dSRF) expression, an intervein marker repressed by Dpp signaling. In A9.Gal4:UAS.dSno pupal disks, dSRF expression is highly irregular with no obviously downregulated regions corresponding to vein primordia (Figure 3D). These wing and disk phenotypes are strongly reminiscent of those expressing the dominant-negative allele Mad1 (DNA binding defective but competent to bind Medea) with a variety of drivers, including A9.Gal4 (100% penetrant; data not shown) and 69B.Gal4 (Takaesu et al. 2005). Mad1 dominant-negative effects are due to the titration of Medea into nonfunctional complexes (Takaesu et al. 2005). The similarity of dSno and Mad1 phenotypes suggests that overexpression of dSno antagonizes BMP signaling.

Figure 3.—

dSno overexpression antagonizes BMP signaling. (A) Wild-type wing. (B) A9.Gal4:UAS.dSno[line1A]. The wing is small and has truncated veins and no crossveins. (C) Wild-type pupal wing disk stained for expression of dSRF. Anterior is at the top and distal at the left. L1–L5 vein primordia without dSRF expression are indicated. (D) A9.Gal4:UAS.dSno. The disk is smaller and has an expanded pattern of dSRF with no obvious vein primordia. (E) A9.Gal4:UAS.dSno and UAS.Med[line2A]. Coexpression of Med and dSno rescues the dSno phenotype to nearly wild type in size and vein pattern. (F) A9.Gal4:UAS.dSno and UAS.Mad[line14]. Coexpression of Mad and dSno also rescues the dSno phenotype. (G) A9.Gal4:UAS.dSno and UAS.dSmad2[line6E3]. Coexpression of dSmad2 has little effect. (H) A9.Gal4:UAS.dSno and UAS.Mad1[line7]. Coexpression of Mad1 significantly enhances the dSno mutant phenotype. (I) A9.Gal4:UAS.CA-Tkv[lineA2]. Activated Tkv induces wing overgrowth and ectopic veins. (J) A9.Gal4:UAS.dSno and UAS.CA-Tkv. Coexpression of dSno and activated Tkv suppresses the Tkv phenotype completely; the wing appears similar to those expressing UAS.dSno alone.

We further tested this by coexpressing dSno with Medea (Figure 3E) or Mad (Figure 3F) or dSmad2 (Figure 3G). Coexpression of dSno with Medea or Mad rescues the dSno phenotype to nearly wild type in size and vein pattern. In dSno and Medea coexpressed wings, reduced size was completely eliminated and multiple vein defects were reduced to 28% penetrance. In dSno and Mad coexpressed wings, reduced size was completely eliminated and multiple vein defects were reduced to 19% penetrance. Alternatively, coexpression of dSno with dSmad2 has little effect on the dSno phenotype. In dSno and dSmad2 coexpressed wings, reduced size and multiple vein defects remained 100% penetrant. Coexpression of Mad1 and dSno significantly enhanced the dSno phenotype (Figure 3H). One hundred percent of Mad1 and dSno coexpressing the wings are more abnormal than those expressing either dSno (Figure 3B) or Mad1 (Takaesu et al. 2005). The coexpressing wing is very small and veinless and resembles wings expressing UAS.Dad (Dpp antagonist; Marquez et al. 2001) or dpp class II disk mutants (e.g., dppd5; St. Johnston et al. 1990). The enhanced phenotype suggests that dSno and Mad1 antagonize BMP signaling in distinct ways that have additive effects.

Experiments with a constitutively activated form of the Dpp type I receptor Thickveins (CA-Tkv) are also consistent with our hypothesis. One hundred percent of A9.Gal4:UAS.CA-Tkv wings are overgrown and have numerous ectopic veins as well as vein truncations (Figure 3I). This phenotype is suppressed in 98% of the individuals when UAS.dSno is coexpressed with UAS.CA-Tkv (Figure 3J). In fact, the coexpression phenotype is not much different from A9.Gal4:UAS.dSno alone, indicating that dSno antagonism of Dpp signaling is fully epistatic to activated Tkv. Finally, ubiquitous overexpression of dSno in the embryonic ectoderm with 32B.Gal4 resulted in diskless larvae (data not shown)—a phenotype seen in Mad and Medea null genotypes and in dpp class V disk mutants (e.g., dppd12; St. Johnston et al. 1990). We conclude that overexpression of dSno antagonizes BMP signaling.

dSno is expressed in the embryonic central nervous system and in third instar larvae:

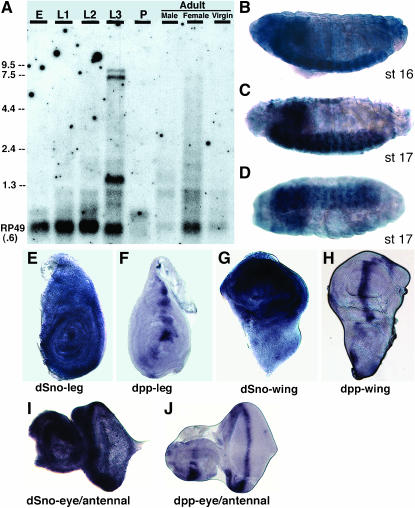

Analysis of dSno transcription utilizing Northern blots identified two strongly hybridizing transcripts that correspond in size to dSnoN and dSnoN2 cDNAs in third instar larvae (Figure 4A). One of these transcripts is weakly visible in adult females. A prominent smaller band, also visible in L3, does not correspond to any of our cDNAs but could represent an alternately spliced version of either SnoA or SnoI.

Figure 4.—

dSno embryonic transcripts are localized to the CNS with the highest level of expression in third instar larvae. An antisense riboprobe generated from CG7233 was hybridized to RNA from a variety of sources. (A) A Northern blot. A riboprobe for RNA encoding RP49 (a ubiquitously expressed ribosomal protein) was used as a control for loading. Lane designations are the following: E, 0- to 24-hr-old embryos; L1–L3, the three larval instars; P, pupae; Virgin, unmated adult females. (B–D) Wild-type embryos. (B) Lateral view, stage 16. dSno expression is widespread in the ectoderm with peak levels present in the CNS (brain and ventral nerve cord). (C) Lateral view, stage 17. dSno expression remains strong and segmentally reiterated peaks of expression are visible in the CNS. (D) Ventral view, stage 17. Expression is restricted to the CNS and segmental peaks of expression are clearly visible. (E–J) dSno and dpp expression in wild-type imaginal disks. (E) dSno expression is widespread in leg disks. (F) dpp expression is localized to the anterior–posterior compartment boundary. (G) dSno expression is widespread in wing disks. (H) dpp expression is localized to the anterior–posterior compartment boundary. (I) dSno expression is widespread in the eye/antennal disk with a clear decrease in the differentiating neurons behind the morphogenetic furrow. (J) dpp expression is localized to the morphogenetic furrow in the eye and in the ventral region of the antennal disk.

In embryos, dSno expression is not visible until embryonic stage 14. Thus, given the large number of functions for BMP signaling that precede stage 14, the absence of early expression suggests that dSno is not utilized as a universal terminator of BMP signaling, a possibility suggested by studies of Sno in mammals. At stage 14, dSno expression is widespread in the ectoderm with a slightly increased concentration in the ventral ectoderm (data not shown). At stage 16, dSno transcripts are still widespread in the ectoderm but they are now most prominent in the brain and ventrally located nerve cord of the central nervous system (CNS; Figure 4B). At stage 17, dSno expression is completely lost outside the CNS while CNS expression remains strong. Within the ventral nerve cord segmentally reiterated peaks of expression are visible (Figure 4, C and D).

As expected from the Northern, dSno is strongly expressed in third instar larval disks. dSno expression is widespread in leg disks with perhaps a slight increase in expression in a semicircular pattern corresponding to the most proximal regions (Figure 4E). In contrast, dpp expression is localized along the anterior–posterior compartment boundary with expression in proximal and distal regions (Figure 4F). dSno expression in the wing blade appears as a semicircular pattern that excludes distal regions (Figure 4G). In contrast, dpp expression is localized along the anterior–posterior compartment boundary with prominent expression in the wing blade, including distal regions (Figure 4H). dSno expression is widespread in the eye/antennal disk and there is a decrease in expression in the differentiating neurons behind the morphogenetic furrow (Figure 4I). In contrast, dpp expression is localized along the morphogenetic furrow in the eye disk and in the ventral region of the antennal disk (Figure 4J). The fact that the expression patterns for dpp and dSno are only partially overlapping led us to wonder if BMP antagonism was a function of endogenous dSno.

dSno loss-of-function mutations cause postembryonic lethality:

To address the possibility that BMP antagonism was a function of engogenous dSno, we analyzed dSno loss-of-function mutations. We began with a strain bearing the l(2)sh1402 chromosome (Oh et al. 2003). This chromosome is lethal when homozygous and we verified by Southern blot that it contains a single P-element insertion. We verified by plasmid rescue that the P element is located 735 bp upstream of CG7233 (dSno). Before commencing a detailed analysis of l(2)sh1402, we wanted to be sure that the P-element insertion was associated with the lethality and that the P-element insertion affected dSno activity and not the function of the adjacent, 7729-bp distant, divergently transcribed gene CG7231.

To ensure that the P-element insertion was associated with the lethality of the l(2)sh1402 chromosome, we conducted a recombination mapping experiment. If the mini-white marked P element was responsible for the lethality, then we predict that, after allowing the l(2)sh1402 chromosome to freely recombine with a wild -type chromosome, the descendant mini-white-marked chromosomes would be homozygous lethal and non-mini-white chromosomes would be homozygous viable. We sibmated >90 recombinant chromosomes of each type and scored at least 50 progeny from each sibmate. We found, consistent with our prediction, that mini-white chromosomes were lethal and that non-mini-white chromosomes were viable.

To ensure that the P-element insertion in l(2)sh1402 affected only dSno function, we conducted complementation tests with three P-element insertion chromosomes associated with CG7231. P{wHy}CG7231 contains an insertion in the 5′ untranslated region of the first protein coding exon of CG7231 on the basis of EST data (FlyBase 2006). This chromosome is homozygous lethal but there is a moderate percentage of escapers. P{SUPor-P}CG7231[KG04307]) has an insertion just upstream of the 5′ untranslated region of CG7231 and it is also homozygous lethal with escapers. P{EPgy2}EY11884 has an insertion in an intron of CG7231 and it is fully viable and fertile as a homozygote. The l(2)sh1402 chromosome fully complemented each of these chromosomes, indicating that its P-element insertion does not affect CG7231 function. l(2)sh1402 is hereafter referred to as dSnosh1402.

Surprisingly, the lethal dSnosh1402 chromosome fully complemented all known deletions affecting the 28D-E region. Of these, complementation with Df(2L)BSC41 (28A4-B1; 28D3-9) was unexpected. The region where dSno is located (28D3,4) is supposedly deleted in this line. We also found that dSnosh1402/Df(2L)BSC41 females were fully fertile. Therefore we generated 200 excision chromosomes from dSnosh1402 as evidenced by phenotypic loss of the mini-white marker carried on the transposon. All of these chromosomes were homozygous lethal and 100% lethal over the parental dSnosh1402 chromosome. This suggested that no precise excisions occurred, an unlikely scenario. In additional complementation tests, 195 of the 200 excision lines were fully viable and fertile over the all 28D-E deletion chromosomes. In the same tests, five excision lines showed varying levels of lethality with Df(2L)BSC41 (Table 1). These five lines fell into two classes. In class I (dSnoEX4B and dSnoEX17B), the number of viable progeny bearing the excision chromosome and Df(2L)BSC41 was ∼40% of the expected number and these females were absolutely sterile. In class II (dSnoEX95A, dSnoEX34A, and dSnoEX71B), the number of progeny with the excision and Df(2L)BSC41 was ∼60% of expected and these females were either weakly or fully fertile.

TABLE 1.

Imprecise excision of the P element in dSnosh1402 generates two classes of mutations

| Genotype | % of expected | Females fertile? |

|---|---|---|

| dSnosh1402/Df(2L)BSC41 | 98 | Yes |

| Imprecise excisions (5 lines) | ||

| Class I | ||

| dSnoEX4B/Df(2L)BSC41 | 36 | No |

| dSnoEX17B/Df(2L)BSC41 | 40 | No |

| Class II | ||

| dSnoEX95A/Df(2L)BSC41 | 57 | Weak, 2–3 adults each |

| dSnoEX34A/Df(2L)BSC41 | 59 | Weak, 2–3 adults each |

| dSnoEX71B/Df(2L)BSC41 | 60 | Yes |

| Precise excisions (195 lines) | ||

| dSnoEX8B/Df(2L)BSC41 | 98 | Yes |

| dSnoEX9B/Df(2L)BSC41 | 107 | Yes |

| dSnoEX10B/Df(2L)BSC41 | 103 | Yes |

To clarify these complex complementation results, we examined the stage of lethality for dSnosh1402 and the class I excision lines (dSnoEX4B and dSnoEX17B) as homozygotes and as heterozygotes with dSnosh1402 (Table 2). dSnosh1402 homozygotes and dSnosh1402/dSnoEX17B individuals die at midpupal stage. Lethality for other genotypes occurred earlier: from first instar larval for dSnoEX4B/dSnoEX4B to the larval–pupal boundary for dSnosh1402/dSnoEX4B. dSnosh1402/dSnoEX4B animals pupariate but do not differentiate adult tissue. The nonembryonic lethality for all genotypes is consistent with late-stage dSno expression in embryos.

TABLE 2.

Expression of UAS.dSno rescues dSno mutant genotypes

| Genotype | Stage of lethality | Rescue with UAS.dSno expression? |

|---|---|---|

| dSnosh1402/dSnosh1402 | Midpupal | Adults (males only, wing defects) |

| dSnosh1402/dSnoEX4B | Larval–pupal boundary | Adults (males only, wing defects) |

| dSnosh1402/dSnoEX17B | Midpupal | Adults (males and females, wing defects) |

| dSnoEX4B/dSnoEX4B | First instar larval | No |

| dSnoEX4B/dSnoEX17B | Third instar larval | Adults (males only, wing defects) |

| dSnoEX17B/dSnoEX17B | Third instar larval | Adults (males and females, wing defects) |

We then asked if the lethality in these genotypes was specifically due to loss of dSno function in rescue experiments. Since constitutive ectodermal expression of UAS.dSno (e.g., with 32B.Gal4) is lethal, we utilized Hsp70.Gal4 to express UAS.dSno in each mutant. We utilized a variety of heat-shock regimes guided by the dSno temporal expression pattern and the stage of lethality for each genotype. We found that application of a heat shock at 10 hr and again at 4 days of age to be most successful. We were able to rescue all of these absolutely lethal genotypes to adulthood except dSnoEX4B homozygotes (Table 2).

Rescue was most robust for the dSnosh1402/dSnoEX17B trans-heterozygous genotype. Here we recovered individuals of both sexes and obtained ∼53% of the expected adults. For the dSnoEX17B homozygous genotype, adults of both sexes were also recovered but at a slightly lower rate. Rescued adults of both genotypes had a held-out wing phenotype similar to that seen in dppd-ho mutants. This suggested that there was a delicate balance between providing enough dSno to rescue but not enough to antagonize Dpp signaling.

For three of the rescued genotypes (dSnosh1402/dSnosh1402, dSnoEX4B/dSnoEX17B, and dSnosh1402/dSnoEX4B), the number of recovered adults was 5–10% of expected and only males were obtained. We speculate that in the ovary where abberant Dpp signaling can lead to the formation of germline stem cell tumors (Xi et al. 2005) dSno function is exquisitely regulated and we did not achieve a fine-enough balance. Alternatively, the lack of females may simply be stochastic, given the percentage of rescued adults. Overall, our rescue data suggest that the postembryonic lethality in all dSno mutant genotypes except dSnoEX4B homozygotes is due to the loss of dSno function.

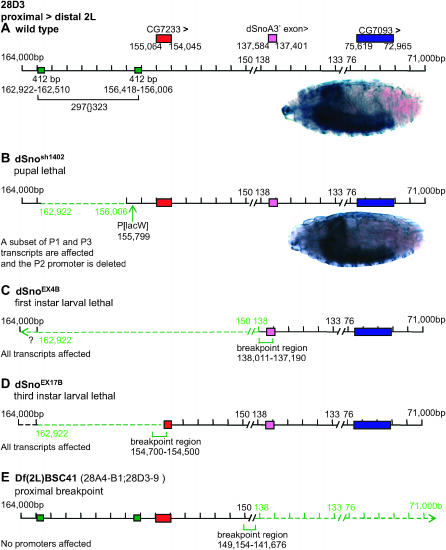

We then characterized the lesions of the dSnosh1402, dSnoEX4B, and dSnoEX17B chromosomes. The location of a P{lacW} insertion in dSnosh1402 was previously reported but only the 5′-end of the P was analyzed (Oh et al. 2003). We identified sequences flanking the 5′- and 3′-ends of the P element and determined that it is inserted precisely between nucleotides 155,798 and 155,799 of the genomic scaffold (Figure 5B). The P element is in the 5′ untranslated region of the exon containing the dSno initiator methionine in three of the four cDNAs that begin at the potential promoter 1 and four of the five cDNAs that begin at our proposed promoter 3 (see Figure 2).

Figure 5.—

Molecular characterization of four dSno mutants. (A) Wild-type map of the dSno locus and the dSno expression pattern in a stage 17 embryo. (B–D) Mutations affecting dSno. Alterations are shown in green with dashed lines indicating regions that are deleted. (B) dSnosh1402 is a pupal lethal that contains two lesions. There is a precise insertion of a P{lacW} transposon between scaffold 155,798 and 155,799 and a precise deletion of the 297TE removing nucleotides 162,922–156,006 (6917 bp deleted). (C) dSnoEX4B is a first instar lethal with a >17.8-kb deletion. (D) dSnoEX17B is a third instar lethal with a 1.5-kb deletion. (E) Df(2L)BSC41 is a visible deletion with a proximal breakpoint in 28D3,4. This breakpoint begins just upstream of the dSnoA unique exon and the deletion extends distally beyond the dSno locus.

Unexpectedly, analysis of sequences flanking the 3′-end of the P element revealed a precise deletion of the 297 retrotransposon in dSnosh1402. The deletion begins 207 bp upstream of the P element and removes nucleotides 162,922–156,006 of the scaffold (6917 bp). The deletion completely removes our proposed promoter 2 and is predicted to impact transcription from the other putative promoters (promoter 1 and promoter 3). Nevertheless, in dSnosh1402 homozygotes, dSno embryonic expression appears wild type (Figure 5B)—consistent with survival to midpupal stage.

The deletion of the 297TE in dSnosh1402 suggests an explanation of why we obtained no homozygous viable excision lines. The 195 homozygous lethal excision lines that are also lethal over dSnosh1402, but viable and fully fertile over Df(2L)BSC41, contain precise excisions. The lethality in these lines may be due to homozygosity for the 297TE deletion. This suggests that a putative dSno promoter (promoter 2) that lies within the 297TE is required for viability and that the other five excision lines are probably imprecise excisions.

Molecular analysis shows that dSnoEX4B contains a deletion of >17.8 kb (Figure 5C). The deletion removes the dSno homology domain at the 5′-end of all dSno proteins. Two of the proposed dSno promoters (promoter 2 and promoter 3) are also deleted. Mapping data on the proximal breakpoint were ambiguous and the presence of the putative promoter 1 is uncertain. However, the inability to rescue the lethality of this mutant with UAS.dSno suggests that one or more genes upstream of dSno are affected. Clearly, dSnoEX4B is a protein null allele.

dSnoEX17B contains a deletion of 1.5 kb (Figure 5D). The distal breakpoint falls within the dSno homology domain while the proximal breakpoint does not extend beyond the 297TE deletion. The deletion truncates the 5′-end of all dSno proteins and two of our putative dSno promoters (promoter 2 and promoter 3) may be deleted. However, it is possible that a transcript from the potential promoter 1 could splice to a cryptic site downstream within the remaining open reading frame. Such a transcript could create a truncated protein initiated at methionine136 that would contain the region of the dSno homology domain containing the Smad4 interaction sites. Thus, dSnoEX17B is either a genetic null or a very strong hypomorph.

The shortest isoform (dSnoI) fulfills all dSno functions necessary for viability:

The complex complementation pattern of dSnosh1402 and its excision lines with Df(2L)BSC41 remained unexplained so we characterized the lesion in the Df(2L)BSC41 chromosome. Df(2L)BSC41 is a cytologically visible deletion removing sequences between 28A4-B1 and 28D3-9 that was generated by a dual P-element mobilization scheme (Parks et al. 2004). The distal element is P{lacW}l(2)k05404 in 28C7-9 and the proximal element is EP(2)0946 in 28D3-5. First, EP(2)0946 and transpose were placed in the same fly and then P{lacW}l(2)k05404 was added. In the third generation, according to the model, an interaction between the simultaneously mobilized P elements deletes all genetic material between them.

EP(2)0946 is located ∼10 kb (scaffold 173,354) proximal to the most proximal exon of dSno. As a result, the model predicts that dSno (scaffold 163,026–71,178) is fully deleted in Df(2L)BSC41. However, when we mapped the Df(2L)BSC41 breakpoint in 28D3-9, we found that it begins between scaffold 149,154 and 141,676 at a location ∼30 kb proximal to the EP(2)0946 insertion point (Figure 5E). The Df(2L)BSC41 deletion begins just upstream of the dSnoA unique exon and removes the 3′-end of the dSno locus. The 3′-ends of dSnoA, dSnoN, and dSnoN2 are absent, yet the three potential dSno promoters and the exon encoding the dSno homology domain are present. The shortest isoform (dSnoI) is present in its entirety.

A simple explanation for the discrepancy between predicted and actual breakpoints in Df(2L)BSC41 is that there was a local jump by EP(2)0946 in the first generation of the scheme. Then, after the second P element was added, the deletion producing interaction occurred. This possibility is supported by inverse PCR experiments (not shown) indicating that in Df(2L)BSC41 neither P element remains in its original position, neither P element is intact, and both P elements made jumps during the mobilization scheme.

The observation that the deletion in Df(2L)BSC41 is the mirror image of the deletions in dSnoEX4B and dSnoEX17B provides an explanation for the reduction in fertility for these heterozygous females. dSnoI proteins generated from Df(2L)BSC41 are insufficient to perform all functions necessary for female fertility in the complete absence of dSno expression from dSnoEX4B and dSnoEX17B. The Df(2L)BSC41 breakpoint observation also provides an explanation for the fact that dSnosh1402 and its 195 precise excision lies are fully viable and fertile over this chromosome. In these heterozygous genotypes, dSnoI proteins expressed from Df(2L)BSC41 fully compensate for the absence of our proposed dSno promoter 2 in the precise excisions and for the additional effects of the P{lacW} insertion in dSnosh1402. Taken together, the analyses of Df(2L)BSC41 indicate that dSnoI can fulfill all dSno functions necessary for viability but not for female fertility.

dSno, babo, and dSmad2 mutants show similar defects in optic lobe development:

The pronounced expression of dSno in the CNS beginning at embryonic stage 16 prompted us to examine this tissue for developmental defects in dSno mutants. BMPs regulate the growth of the neuromuscular junction synapse (e.g., Marques et al. 2002) and phosphorylated Mad (pMad) normally accumulates in motoneuron nuclei beginning at embryonic stage 15. However, we saw no alteration in the intensity or pattern of pMad accumulation in the CNS, or in any other embryonic tissue, in dSno mutant embryos. We also examined the neuromuscular junction of dSno mutant third instar larvae with the presynaptic marker Csp (Zinsmaier et al. 1994) and observed no obvious difference in bouton numbers or overall synapse size. Together, these results suggest that dSno does not modulate BMP signaling in motor neurons.

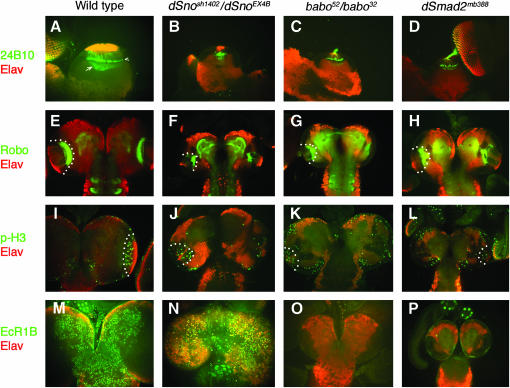

The fact that the majority of dSno mutants die after pupation without differentiating into pharate adults (Table 2) is similar to our observations of strong baboon (babo) and dSmad2 mutants (Brummel et al. 1999). Baboon is an Activin type I receptor and we have recently characterized babo and dSmad2 phenotypes in more detail (M. B. O'Connor, unpublished data). In these mutants we found pronounced optic lobe defects related to photoreceptor innervation of the lamina and medulla. As shown in Figure 6A, axons of photoreceptors R1–6 normally terminate at the lamina, while R7–8 project deeper into the brain, forming an elaborate lattice-like network with expanded growth cones that make contact with the medulla neuropil. In both babo and dSmad2 mutants, R1–6 axons project into the brain and form a relatively normal but very reduced lamina plexus while R7 and R8 axons never form a normal lattice network and their growth cones are collapsed (Figure 6, C and D). Intriguingly, dSno mutant larvae exhibit a very similar phenotype (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.—

Similarity of dSno, babo, and dSmad2 optic lobe phenotypes. All brain lobes are from crawling third instar lava. (A–D) Optic lobes stained with anti-24B10 (green) and Elav (red) antibodies. In the wild type, note the large lamina cap, lamina plexus (arrowhead) and R7–R8 lattice area in the medulla (arrow). In all mutants, these areas are much reduced. (E–H) Larval brains stained with anti-Robo (green) and Elav (red). The white dots outline Robo staining in the medulla neuropil. Note the reduction and altered morphology of the neuropil in all mutants. (I–L) Optic lobes stained with antiphospho-histone H3 (green) and Elav (red). The white dots outline the inner proliferation zone. Note that all mutants show reduced numbers of cells in M phase. (M–P) Brain lobes stained with anti-EcR-1B (green) and Elav (red). Note that both babo and dSmad2 mutants have greatly reduced EcR-1B expression while dSno mutants do not.

We also found that the medulla neuropil is significantly reduced in size and its morphology is altered in babo and dSmad2 mutants (Figure 6; compare G and H to E). Again, dSno mutant larval brains show a similar alteration in medulla neuropil size and architecture. In both babo and dSmad2 mutants, these defects likely result as a secondary consequence of reduced cell proliferation within the optic lobes of the brain (Brummel et al. 1999). Likewise, we find that dSno mutants show reduced numbers of cells in M phase as assayed by phospho-histone H3 staining (Figure 6, I –L).

These results are consistent with the hypothesis that dSno mediates Babo signaling in the optic lobes to maintain correct proliferation rates in neuroblasts and/or their daughter cells during larval development. However, no direct transcriptional targets of Babo signaling that regulate proliferation in the optic lobe are known. At present, only the ecdysone receptor-1B isoform (EcR-1B) has been identified as a target of Babo and dSmad2 signaling in mature neurons of the CNS. In the absence of either gene, EcR-1B expression is dramatically reduced (Zheng et al. 2003; Figure 6 compare M to O and P). In contrast, dSno mutants exhibit apparently normal levels of EcR-1B expression (Figure 6N). This result implies that dSno is not required for Babo-mediated responses in mature neurons of the CNS.

dSno promotes the interaction of Medea with dSmad2:

To resolve the apparent contradiction between the effect on signaling of dSno overexpression (antagonism) and the role identified in dSno mutants (mediation), we examined dSno biochemically. We used expression constructs encoding Flag or T7 epitope-tagged Medea, Mad, and dSmad2 and coexpressed various combinations in COS1 cells. We were able to clearly detect interaction of Medea with both dSmad2 and Mad by co-immunoprecipitation (Figure 7A). We next generated a T7-tagged dSno expression construct and coexpressed this with Flag-dSmad2, Mad, or Medea or with a control vector. Complexes were isolated on Flag agarose and analyzed for the presence of coprecipitating dSno by T7 Western blot. T7-dSno was readily detectable in complexes isolated from cells expressing Medea, but not Mad or dSmad2 (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.—

dSno promotes the interaction of Medea with dSmad2. (A) COS1 cells were transfected with Flag or T7 epitope-tagged Mad, dSmad2, or Medea, as indicated. Forty hours after transfection, proteins were isolated on anti-Flag agarose and analyzed by Western blot for the presence of coprecipitating T7-tagged proteins. Expression of Flag and T7 proteins in the lysates was analyzed by Western blot of the lysates (below). (B) COS1 cells were transfected and analyzed as in A, with the indicated Flag expression constructs together with T7-tagged dSno. Following Flag immunoprecipitation, coprecipitating dSno was detected by T7 Western blot. (C) COS1 cells were transfected with T7-dSno and Flag-Mad or dSmad2, with or without T7-Medea as indicated. Protein complexes were analyzed as in A. (D and E) COS1 cells were transfected with the indicated Flag or T7-tagged expression constructs and protein complexes collected on Flag agarose. Both Flag and T7-tagged proteins were detected by Western blot of the Flag immunoprecipitates (top panels) and in the lysates (bottom panels). (F) Flag-Medea interacting proteins were isolated from COS1 cells transfected with the indicated expression constructs and analyzed by T7 Western blot. Expression in the lysates is below. In A–F, positions of coprecipitating proteins are indicated with arrows. The immunoglobulin heavy chain is shown by a bar. In F, proteins were first eluted from the Flag agarose at 37°, so no heavy chain is visible.

Since Medea is a shared partner for both Mad and dSmad2, we next tested whether we could isolate co-complexes containing Medea and dSno together with either Mad or dSmad2. COS1 cells were transfected with T7-dSno and Flag-Mad or dSmad2 with or without T7-Medea. T7-dSno was present in a complex with Flag-dSmad2 only when T7-Medea was also present (Figure 7C). Interestingly, approximately equal amounts of Medea and dSno appeared to coprecipitate with dSmad2, suggesting that much of the Medea that interacts with dSmad2 in this assay is also bound to dSno. In contrast, we did not detect dSno in complex with Mad, even when Medea was present, even though Medea clearly interacted with Mad in this assay. These results suggest that dSno interacts specifically with Medea and that the dSno-Medea complex can interact with dSmad2 but not with Mad.

To test whether incorporation of dSno affected formation of the Medea-dSmad2 complex, we coexpressed Flag-Medea and T7-dSmad2 with or without dSno (Figure 7D). The amount of dSmad2 that coprecipitated with Flag-Medea was clearly increased in the presence of dSno. In the reverse of this experiment, we also observed that an increase in T7-tagged Medea present in Flag-dSmad2 precipitates when dSno was coexpressed (Figure 7E). These results suggest that dSno may promote the formation of Medea-dSmad2 complexes.

To test whether dSno had any effect on the formation of Mad-Medea complexes, we performed similar experiments in which we isolated Flag-Medea and Western blotted for coprecipitating T7-Mad or dSmad2 in the presence or absence of coexpressed dSno. The interaction of Medea with Mad was more readily detectable than with dSmad2 (Figure 7, A and F). However, inclusion of dSno again increased the interaction between Medea and dSmad2. In contrast, we saw no increase in the Medea–Mad interaction when dSno was coexpressed and it appeared that increasing dSno expression decreased the amount of Mad that coprecipitated with Flag-Medea (Figure 7F). Thus it appears that dSno not only may promote interaction of Medea with dSmad2, but also may compete with Mad for Medea interaction, suggesting that dSno may play a role in determining the pathway specificity of Medea.

DISCUSSION

dSno acts like a pathway switch in brain development:

We propose the following hypothesis to resolve what appear to be contradictory roles for dSno in TGFβ signaling (antagonism and mediation): dSno is a BMP-to-Activin pathway switch in brain development. This hypothesis is consistent with our data, with other reports examining neural development in Drosophila and with studies of mammalian neural stem cells.

Three studies of TGFβ signaling in optic lobe development support this hypothesis. A study by Yoshida et al. (2005) showed that Dpp signaling via its receptors Thickveins and Medea is essential for the differentiation of optic lobe neuroblasts into lamina glia and neurons. Our study shows that the Activin receptor Baboon via its signal transducers dSmad2 and dSno is required for the maintenance of neuroblast proliferation. Clearly, during optic lobe development neuroblasts must balance self-renewal via proliferation and the generation of neurons and glia via differentiation. Given its ability to interact with both the Dpp pathway and the Activin receptor pathway, it seems logical that in neuroblasts dSno functions as a pathway switch, shunting Medea away from forming complexes with Mad in the BMP pathway that directs differentiation and toward forming complexes with dSmad2 in the Activin pathway that directs proliferation.

This hypothesis is also consistent with a microarray study of neuroblast differentiation in Drosophila (Egger et al. 2002). In this study, widespread misexpression of glial cells missing, a transcription factor that specifies the fate of differentiating neuroblasts, significantly reduced the expression of dSno. Reduction of dSno expression in differentiated cells fits well with two of our results. First, dSno mutants have no effect on the expression of EcR-1B because this gene is a Baboon target only in mature neurons (Figure 6N). Second, dSno transcript accumulation is reduced in the differentiated cells behind the morphogenetic furrow in the eye disk (Figure 4I). Further, given the analogous roles played by Dpp in the differentiation of optic lobe neuroblasts and the role played by Dpp homologs (BMPs; Bonaguidi et al. 2005) in the differentiation of mammalian neuronal stem cells, it is possible that Sno is also a pathway switch in mammals.

One model for dSno function in optic lobe development is as follows: dSno expression is activated by an unidentified factor in a subset of optic lobe neuroblasts in third instar larvae. In these cells, cytoplasmic dSno (studies of mammalian Sno show several cell types with predominantly cytoplasmic localization) forms complexes with Medea. Subsequently, Dpp signaling from the lamina glia precursor region, capable of reaching all optic lobe neuroblasts, is incapable of inducing differentiation in neuroblasts expressing dSno. Alternatively, Activin functions as a secreted hormone (T. Haerry, personal communication) also capable of reaching all optic lobe neuroblasts. Those expressing dSno are capable of responding to proliferative Activin signals. Thus a balance between proliferation and differentiation is achieved in the optic lobe neuroblast population.

dSno may contain a unique example of developmental evolution:

The dSno locus clearly illustrates the complexity of developmental evolution. Here significant conservation at the protein level (isoform number, structure, and sequence) coexists with a recent transposon insertion that appears to be involved in dSno transcriptional regulation.

Regarding conservation, multiple protein isoforms are rare among growth factor signal transduction pathway components. Sno is the first example of a TGFβ signal transducer with four conserved isoforms. The role that each alternative isoform plays is unknown, but our experience with Df(2L)BSC41 suggests that the shortest (dSnoI) may be sufficient to fulfill nearly all roles, at least under laboratory conditions. Amino acid conservation in the Sno homology domain extends to a large multigene family. The topology of the Sno/CORL/Dachsund tree is similar to that of the Smad family. In both families, fly and human genes cluster together while worm genes are present in a subset of clusters and also fall between clusters. Thus, the Sno/CORL/Dachsund family tree argues against the existence of an Ecdysozoan phylum containing worms and flies. It is consistent with the traditional Coelomate classification that places flies closer to vertebrates than to worms (Newfeld et al. 1999; Newfeld and Wisotzkey 2006).

The presence of a 297TE in the mist of the putative dSno promoter region is the only example we are aware of in which a transposable element may have co-opted regulatory functions for a nearby gene and thereby rendered itself indispensable. There are 57 297TE elements in the D. melanogaster genome but only 18 are full length like the 297{323} insertion in dSno (Kaminker et al. 2002). To determine if the 297TE family is an ancient one in Drosophila, we examined its species distribution by BLAST. We found that 297TE family members are present only in species of the melanogaster group (divergence 44 million years; Tamura et al. 2004). 297TE sequences are absent from other Drosophila species and from other insect phyla. Within the melanogaster group, the relationship between 297TE sequences mirrors the relationship between the species. Thus, the 297TE family entered Drosophila via the common ancestor of the melanogaster group.

Two features of 297{323} suggest that the insertion of a 297TE family member in the putative dSno promoter region is a very recent event. The 412-bp direct repeats in 297{323} are absolutely identical, indicating little time for mutations to accumulate. Second, there is no 297TE upstream of dSno in D. melanogaster's closest relatives, D. simulans and D. sechellia (divergence 5.4 million years; Tamura et al. 2004). Thus, variation in the splice junction between exon 1 and exon 2 in transcripts generated from our proposed dSno promoter 1 and variation in start sites for transcripts generated from the potential promoter 3 (Figure 2) likely result from natural selection for sites that bypass or incorporate the 297TE. The specific developmental processes affected by dSno transcripts generated from within the transposon are unknown, but if they are identified, they will likely be the first example of a transposon positively influencing a specific phenotype.

In summary, our data support the view that dSno functions as a switch in optic lobe development, shunting Medea from the Dpp pathway to the Activin pathway to ensure a proper balance between differentiation (Dpp) and cell proliferation (Activin). Pathway switching in target cells is a previously unreported mechanism for regulating TGFβ signaling and a novel function for Sno/CORL/Dachsund proteins.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark Stapleton for cDNA libraries, Steve Hou and the Bloomington Stock Center for flies, and Aaron Johnson for bringing the l(2)sh1402 strain to our attention. We thank Kevin Cook for insightful discussions, the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for antibodies, Scott Bingham for DNA sequencing, Natasha Emmert for fly pushing, and Wayne Parkhust for assistance with figures. We thank Theo Haerry for sharing data prior to publication. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA095875 to S.J.N. and HD039926 to D.W.). M.B.O. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- Bonaguidi, M., T. McGuire, L. Hu, J. Kan, J. Samanta et al., 2005. LIF and BMP signaling generate separate and discrete types of GFAP-expressing cells. Development 132: 5503–5514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, P., C. Colmenares, E. Stavnezer and S. Hughes, 1993. Sequence and biological activity of chicken SnoN cDNA clones. Oncogene 8: 457–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand, A., and N. Perrimon, 1993. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118: 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummel, T., S. Abdollah, T. Haerry, M. Shimell, J. Merriam et al., 1999. The Drosophila activin receptor Baboon signals through dSmad2 and controls proliferation but not patterning in larval development. Genes Dev. 13: 98–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtiss, J., and M. Mlodzik, 2000. Morphogenetic furrow initiation and progression during eye development in Drosophila: the roles of dpp, hh and eya. Development 127: 1325–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Graca, L., K. Zimmerman, M. Mitchell, M. Kozhan-Gorodetska, K. Sekiewicz et al., 2004. DAF-5 is a Ski oncoprotein homolog that functions in a TGFβ pathway to regulate C. elegans dauer development. Development 131: 435–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger, B., R. Leemans, T. Loop, L. Kammermeier, Y. Fan et al., 2002. Gliogenesis in Drosophila, analysis of downstream genes of glial cells missing in the embryonic nervous system. Development 129: 3295–3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FlyBase, 2006. FlyBase: anatomical data, images and queries. Nucleic Acids Res. 34: D484–D488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, K., I. Hanson, A. Brown, L. Lettice and R. Hill, 1998. Mammalian and Drosophila dachshund genes are related to the Ski proto-oncogene and are expressed in eye and limb. Mech. Dev. 74: 121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, C., B. Bartholin, S. Newfeld and D. Wotton, 2003. Drosophila TGIF proteins are transcriptional activators. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 9262–9274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminker, J., C. Bergman, B. Kronmiller, J. Carlson, R. Svirskas, et al., 2002. The transposable elements of D. melanogaster euchromatin: a genomics perspective. Genome Biol. 3: 0084.1–008420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S., K. Tamura and M. Nei, 2004. MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinformatics 5: 150–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., C. Turck, J. Teumer and E. Stavnezer, 1986. Unique sequence Ski in Sloan-Kettering retroviruses with properties of a cell-derived oncogene. J. Virol. 57: 1065–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, K., S. Stroschein, W. Wang, D. Chen, E. Martens et al., 1999. Ski interacts with the Smad proteins to repress TGFβ signaling. Genes Dev. 13: 2196–2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas, A., 1996. Prediction and analysis of coiled-coil structures. Methods Enzymol. 266: 513–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques, G., H. Bao, T. Haerry, M. Shimell, P. Duchek et al., 2002. The Drosophila BMP type II receptor Wit regulates neuromuscular synapse morphology and function. Neuron 33: 529–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez, R., M. Singer, N. Takaesu, R. Waldrip, Y. Kraytsberg et al., 2001. Transgenic analysis of the Smad family of TGFβ signal transducers in Drosophila suggests new roles and interactions between family members. Genetics 157: 1639–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué, J., J. Seoane and D. Wotton, 2005. Smad transcription factors. Genes Dev. 19: 2783–2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuhara, E., T. Nakatani, Y. Minaki, Y. Sakamoto and Y. Ono, 2005. Corl1: a novel neuronal lineage-specific transcriptional corepressor for the homeodomain transcription factor Lbx1. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 3645–3655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newfeld, S., and W. Gelbart, 1995. Identification of two Drosophila TGFβ family members in the grasshopper Schistocerca americana. J. Mol. Evol. 41: 155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newfeld, S., and R. Wisotzkey, 2006. Molecular evolution of Smad proteins, pp 15–35 in Smad Signal Transduction: Smads in Proliferation, Differentiation and Disease, edited by C.-H. Heldin and P. ten Dijke. Springer-Verlag, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- Newfeld, S., A. Mehra, M. Singer, J. Wrana, L. Attisano et al., 1997. Mad participates in a DPP/TGFβ responsive serine-threonine kinase signal transduction cascade. Development 124: 3167–3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newfeld, S., R. Wisotzkey and S. Kumar, 1999. Molecular evolution of a developmental pathway, phylogenetic analyses of TGFβ family ligands, receptors and Smad signal transducers. Genetics 152: 783–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, R., and W. Gelbart, 1998. Identification of chromosomal regions involved in dpp function in Drosophila. Genetics 149: 203–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, N., S. Sasamoto, S. Ishii, T. Date, M. Matsui et al., 1989. Isolation of human cDNA clones of Ski and Sno. Nucleic Acids Res. 17: 5489–5500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, T., M. Khan, S. Kaul, H. Dong, R. Wadhwa et al., 1999. Ski is a component of the histone deacetylase complex required for transcriptional repression by Mad and thyroid hormone receptor. Genes Dev. 13: 412–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S., T. Kingsley, H. Shin, Z. Zheng, H. Chen et al., 2003. A P-element insertion screen identified mutations in 455 novel essential genes in Drosophila. Genetics 163: 195–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks, A., K. Cook, M. Belvin, N. Dompe, R. Fawcett et al., 2004. Systematic generation of high-resolution deletion coverage of the D. melanogaster genome. Nat. Genet. 36: 288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson-White, S., and R. Crittenden, 1997. Proto-oncogene Sno expression, alternative isoforms and immediate early serum response. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 2930–2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson-White, S., and M. McDuffie, 2003. Defective T-cell activation is associated with augmented TGFβ sensitivity in mice with mutations in Sno. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 5446–5459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pothof, J., G. Van Haaften, K. Thijssen, R. Kamath, A. Fraser et al., 2003. Identification of genes that protect the C. elegans genome against mutations by genome-wide RNAi. Genes Dev. 17: 443–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, K., S. Wilson and S. Bonni, 2005. SnoN is a cell type-specific mediator of TGFβ responses. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 13037–13046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinagawa, T., H. Dong, M. Xu, T. Maekawa and S. Ishii, 2000. The Sno gene, which encodes a component of histone deacetylase complex, acts as a tumor suppressor in mice. EMBO J. 19: 2280–2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitnikova, T., 1996. Bootstrap test for phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 13: 605–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Johnston, R., F. Hoffmann, R. Blackman, D. Segal, R. Grimaila et al., 1990. Molecular organization of dpp. Genes Dev. 47: 1114–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroschein, S., W. Wang, S. Zhou, Q. Zhou and K. Luo, 1999. Negative feedback regulation of TGFβ signaling by the SnoN oncoprotein. Science 286: 771–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroschein, S., S. Bonni, J. Wrana and K. Luo, 2001. Smad3 recruits the anaphase-promoting complex for ubiquitination and degradation of SnoN. Genes Dev. 15: 2822–2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, M., R. Wisotzkey and S. Newfeld, 2001. A screen for modifiers of dpp mutant phenotypes identifies lilliputian, the only member of the Fragile-X/Burkitt's lymphoma family of transcription factors in Drosophila. Genetics 157: 717–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaesu, N., A. Johnson, O. Sultani and S. Newfeld, 2002. Combinatorial signaling by an unconventional Wg pathway and the Dpp pathway requires Nejire (CBP/p300) to regulate dpp expression in posterior tracheal branches. Dev. Biol. 247: 225–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaesu, N., E. Herbig, D. Zhitomersky, M. O'Connor and S. Newfeld, 2005. DNA-binding domain mutations in Smad genes yield dominant negative proteins or a neomorphic protein that can activate Wg target genes in Drosophila. Development 132: 4883–4894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K., S. Subramanian and S. Kumar, 2004. Temporal patterns of Drosophila evolution revealed by mutation clocks. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21: 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J., T. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin and D. Higgins, 1997. The CLUSTAL-X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 4876–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, S., L. Soustelle, A. Giangrande, D. Umetsu, S. Murakami et al., 2005. Dpp signaling controls development of the lamina glia for retinal axon targeting in the visual system. Development 132: 4587–4598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J., A. Krawitz, J. Chai, W. Li, F. Zhang et al., 2002. Structural mechanism of Smad4 recognition by the nuclear oncoprotein Ski: insights on Ski-mediated repression of TGFβ signaling. Cell 111: 357–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K., Y. Yang, C. Wang, M. Davoli, M. D'Amico et al., 2003. DACH1 inhibits TGFβ signaling through binding Smad4. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 51673–51684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi, R. C. Doan, D. Liu and T. Xie 2005. Pelota controls self-renewal of germline stem cells by repressing a Bam-independent differentiation pathway. Development 132: 5365–5374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X., J. Wang, T. Haerry, A. Wu, J. Martin et al., 2003. TGFβ signaling activates steroid hormone receptor expression during neuronal remodeling in the Drosophila brain. Cell 112: 303–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinsmaier, K., K. Eberle, E. Buchner, N. Walter and S. Benzer, 1994. Paralysis and early death in cysteine string protein mutants of Drosophila. Science 263: 977–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]