Abstract

The 90-kD molecular chaperone hsp90 is the key component of a multiprotein chaperone complex that facilitates folding, stabilization, and functional modulation of a number of signaling proteins. The components of the animal chaperone complex include hsp90, hsp70, hsp40, Hop, and p23. The animal Hop functions to link hsp90 and hsp70, and it can also inhibit the ATPase activity of hsp90. We have demonstrated the presence of an hsp90 chaperone complex in plant cells, but not all components of the complex have been identified. Here, we report the isolation and characterization of soybean (Glycine max) GmHop-1, a soybean homolog of mammalian Hop. An analysis of soybean expressed sequence tags, combined with preexisting data in literature, suggested the presence of at least three related genes encoding Hop-like proteins in soybean. Transcripts corresponding to Hop-like proteins in soybean were detected under normal growth conditions, and their levels increased further in response to stress. A recombinant GmHop-1 bound hsp90 and its binding to hsp90 could be blocked by the tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain of rat (Rattus norvegicus) protein phosphatase 5. Deletion of amino acids 325 to 395, adjacent to the TPR2A domain in GmHop-1, resulted in loss of hsp90 binding. In a minimal assembly system, GmHop-1 was able to stimulate mammalian steroid receptor folding. These data show that plant and animal Hop homologs are conserved in their general characteristics, and suggest that a Hop-like protein in plants is an important cochaperone of plant hsp90.

The highly conserved and abundant molecular chaperone hsp90 is distinct from other chaperones in that it plays a key role in signal transduction networks, cell cycle control, protein degradation, and genomic silencing (Young et al., 2001). A critical dependence on hsp90 has been established for animal steroid hormone receptors (SRs), several Ser/Thr and Tyr kinases, and other distinct proteins (Pratt and Toft, 1997; Buchner, 1999). Two key features regarding the mechanism of hsp90 action have emerged over the last decade: (a) hsp90 lies at the center of a multiprotein chaperone complex that facilitates the folding of client proteins into their stable or activatable conformations, and (b) hsp90 is an ATP-dependent chaperone. The study of hsp90 complexes, in particular those involving animal SRs, has revealed that five crucial chaperone components participate in the conformational regulation of hsp90 client proteins. These include hsp90 and hsp70 and their cochaperones Hop, p23, and hsp40. The high-Mr immunophilins are also recovered in hsp90 complexes, but these appear to be nonessential in receptor folding assays (Pratt and Toft, 1997). The cochaperone Cdc37p/p50cdc37 is predominantly found in hsp90-kinase complexes (Pratt and Toft, 1997).

Hop (hsp70- and hsp90-organizing protein) derives its name from its role as an adapter protein that can bind to both hsp90 and hsp70 simultaneously, bringing them into close proximity (Chen and Smith, 1998). It is proposed that hsp70 first contacts the client protein and then facilitates the transfer of the client protein to hsp90 (Young et al., 2001). The role of Hop at this early stage of assembly appears significant in that it targets hsp90 to hsp70-client protein complexes. After loading of hsp90 onto the client protein, Hop and hsp70 dissociate and the hsp90-client protein complex progresses to the mature form (Smith et al., 1995; Chen et al., 1996b). Although Hop is considered obligatory for the formation of functional SR complexes, reconstitution studies with purified proteins have indicated that Hop accelerates the rate of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) heterocomplex assembly, but is not essential for GR folding (Morishima et al., 2000). The final steps of receptor maturation are characterized by the appearance of p23 and a high-Mr immunophilin in SR-hsp90 complexes (Johnson et al., 1996). The cochaperone p23 binds specifically to the ATP-bound conformation of hsp90 (Sullivan et al., 1997) and stabilizes SR-hsp90 complexes in the steroid-binding state (Dittmar et al., 1997). The immunophilins are not required for folding the receptor to the hormone-binding state, but may influence steroid signaling (Cheung and Smith, 2000), or link signaling proteins to the movement machinery and target their direction of movement (Pratt et al., 2001).

Hop binds preferentially to hsp90 and hsp70 in their ADP-bound conformations (Johnson et al., 1998). The binding of Hop to hsp70 is via an N terminus tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain of Hop and to hsp90 is via a central TPR domain (Chen et al., 1996b). Another important role for Hop as a regulator of the ATPase activity of hsp90 has emerged recently. The ATPase activity of hsp90, which is vital for its in vivo functions (Panaretou et al., 1998), is completely inhibited by binding of the yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) Hop ortholog Sti1p (Prodromou et al., 1999), referred to herein as ScHop. Evidence that hsp90 and Hop interact in vivo comes from genetic studies conducted in yeast (Chang et al., 1997). Mutations that eliminated ScHop or reduced hsp90 concentrations had minimal effect on growth at normal temperatures, but when combined, the mutations greatly reduced growth. Also, deletion of ScHop significantly inhibited SR signaling in yeast. Although ScHop is not essential for growth, an essential Hop homolog Cns1p has been identified in yeast (Dolinski et al., 1998; Marsh et al., 1998). Cns1p interacts with hsp90, but whether it links hsp90 and hsp70 remains to be seen.

Homologs of Hop have been identified in several organisms (Chen and Smith, 1998). With the exception of a report in 1995 on a soybean (Glycine max) gene encoding a TPR domain protein that shares amino acid identities of 44% and 38% with the human (Homo sapiens) and yeast Hop homologs, respectively (Torres et al., 1995), no other information on a plant Hop homolog is available. We have demonstrated the presence of an hsp90-based chaperone complex in plant cells and to date have identified hsp90, hsp70, and high-Mr immunophilins in these complexes (Owens-Grillo et al., 1996; Stancato et al., 1996; Reddy et al., 1998). Recently, we have identified a 70-kD protein in wheat (Triticum aestivum) that co-immunoprecipitates with hsp90 and hsp70 and shares amino acid similarity with Hop (P. Krishna and K.C. Kanelakis, unpublished data). The 70-kD wheat protein was detected by the F5 antibody raised against avian Hop (Smith et al., 1993), which recognized a similar protein in cell lysates of other monocot plants but not of dicot plants. Our data thus far indicates that the plant hsp90 chaperone complex encompasses some unique characteristics. This is not unexpected because plants have a unique environment and structural organization. To fully characterize the plant hsp90 system, it is necessary to isolate the various members of the complex and to study their interactions and functions. In the present study, we isolated a cDNA encoding a Hop-like protein from a dicot plant and studied its expression, as well as its interaction with hsp90.

RESULTS

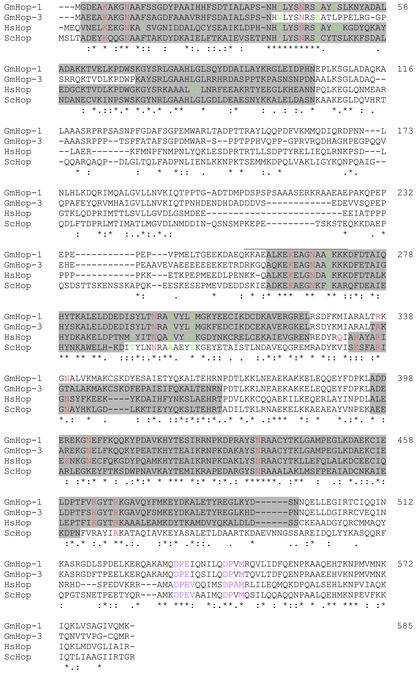

Cloning of a Novel Soybean cDNA with Similarity to Hop

A search of 2,000 soybean expressed sequence tags (ESTs) from a seed coat cDNA library resulted in the identification of a sequence showing significant similarity (E = 10−22) to ScHop. The cDNA of the novel sequence contains an open reading frame of 1,755 nucleotides and deduced 585 amino acid residues, predicting a translated protein of 67.2 kD (Fig. 1). The encoded protein GmHop-1 showed amino acid identities of 72%, 69%, 47%, and 42% with a potential stress-induced protein of Arabidopsis, GMSTI of soybean cv Williams (referred to herein as GmHop-3), human Hop (referred to herein as HsHop), and ScHop, respectively. All Hop homologs identified thus far contain multiple TPR motifs, known to be involved in protein-protein interactions (Honoré et al., 1992; Smith et al., 1993; Torres et al., 1995; Blatch et al., 1997). To determine if GmHop-1 shares this feature, ProfileScan was used to identify conserved protein domains. Seven potential TPR motifs located within amino acids 2 through 103 (TPR1), 257 through 324 (TPR2A), and 396 through 496 (TPR2B) were identified in GmHop-1 (shaded regions in Fig. 1). Maximum conservation of sequence in homologs of different origin was found within the TPR domains. A perfectly conserved decamer (NHVLYSNRSA) within TPR1, and a pentamer (YSNRAA) within TPR2B, were also detected in GmHop-1. Several amino acids within the possible nuclear localization signal located between amino acids 253 and 271 (indicated by a line above the residues) were seen to be conserved. The DPEV and DPAM sites located in the C-terminal end of HsHop, mutations in which impaired binding to hsp70 (Chen and Smith, 1998), are partially conserved in GmHop-1 (indicated in magenta). Residues of HsHop involved in interactions with the EEVD motif in hsp90 and hsp70 (Scheufler et al., 2000) are shown in red and green in Figure 1. The residues involved in hydrophobic and van der Waals contacts with the EEVD motif (in green) provide specificity for hsp70 and hsp90 binding by TPR1 and TPR2A, respectively (Scheufler et al., 2000). As can be seen in Figure 1, not all of these residues are conserved in GmHop-1.

Figure 1.

Comparative alignment of the amino acid sequences of Hop homologs. The deduced amino acid sequences of GmHop-1 (soybean cv Harosoy 63), GmHop-3 (soybean cv Williams, X79770), HsHop (M86752), and ScHop (M28486) were aligned using the Clustal multiple sequence alignment program. Potential TPR domains are shaded and a potential nuclear localization signal is indicated by a line above the residues. Asterisks indicate conserved residues. Double and single dots indicate strong and weak conservative substitutions, respectively. The numbers on the right indicate the last amino acid on that line for the GmHop-1 sequence only. TPR residues of the two-carboxylate clamp and other residues involved in electrostatic interactions with the EEVD motif are shown in red, and residues involved in hydrophobic and van der Waals contacts with the EEVD motif are shown in green (taken from Scheufler et al., 2000). The DPEV and DPAM sites are indicated in magenta.

GmHop Is Encoded by a Multigene Family

In yeast, a single gene encodes ScHop (Chang et al., 1997), although a distantly related protein Cns1p has also been identified (Dolinski et al., 1998; Marsh et al., 1998). To determine the number of genes encoding Hop-like proteins in soybean, we searched 284,714 soybean ESTs for transcripts with similarity to GmHop-1 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Highly significant matches were selected and sequence polymorphisms were carefully scrutinized. On the basis of these sequence comparisons, the ESTs appear to represent two closely related genes that share approximately 90% nucleotide identity, GmHop-1 and GmHop-2 (Table I). Sixteen ESTs represented GmHop-1 transcripts and the remaining 15 ESTs matched GmHop-2. None of the ESTs matched GMSTI, a previously described Hop homolog from soybean (Torres et al., 1995), hereafter referred to as GmHop-3. The GmHop-3 cDNA shares 80% nucleotide identity with GmHop-1. Further queries of the soybean EST database using the GmHop-3 sequence did not reveal any matching sequences. Overall, this analysis shows that there are at least three Hop-like genes within the soybean genome, and that GmHop-1 and GmHop-2 are preferentially expressed. Analysis by DNA-blot hybridization using a probe corresponding to GmHop-1 indicated that this gene was present as two closely related copies (not shown), and, thus, substantiated the EST results. Closely related pairs of genes, such as GmHop-1 and GmHop-2, are prevalent in soybean because this plant may be considered an allotetraploid (Hymowitz and Singh, 1987). Thus, it is possible that GmHop-3 may also have a pair mate, GmHop-4.

Table I.

ESTs corresponding to GmHop-1 and GmHop-2

| Organs | GmHop-1a | GmHop-2b |

|---|---|---|

| Seed coat (Harosoy) | 1 | – |

| Young cotyledon | – | 1 |

| Degenerating cotyledon | 1 | – |

| Etiolated hypocotyl infected with pathogen | – | 1 |

| Epicotyl | 1 | – |

| Leaf of drought-stressed plant | 1 | – |

| Root | 2 | 1 |

| Root of supernodulating mutant | – | 1 |

| Mature flower | – | 3 |

| Vegetable bud | 1 | – |

| Young seed | 1 | – |

| Germinating shoot at 4°C for 2 d | – | 1 |

| Somatic embryo | 1 | 1 |

| Whole seedling | 2 | – |

| Seedling induced for symptoms of SDSc | 1 | – |

| Seedling minus cotyledon at 40°C for 1 h | 3 | 3 |

| Various organs and stages of development | 1 | 3 |

| Total ESTs | 16 | 15 |

ESTs obtained from 14 different cDNA libraries.

ESTs obtained from 11 different cDNA libraries.

SDS, Sudden death syndrome.

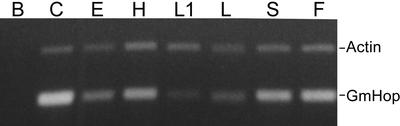

GmHop Transcript Expression in Different Organs of Soybean

In chicken (Gallus gallus) and mouse (Mus musculus), Hop is constitutively expressed in all organs tested (Smith et al., 1993; Blatch et al., 1997). As a first step in the characterization of GmHop, we examined its transcript expression in different organs of soybean. GmHop transcripts were barely detectable in leaves and only a weak signal corresponding to these transcripts in other soybean organs was obtained by RNA gel-blot analysis. However, using the more sensitive reverse transcription (RT)-PCR method, we found that GmHop transcripts were expressed in all organs tested, with maximal expression in cotyledons, followed by shoots and flowers (Fig. 2). The ubiquitous expression of GmHop transcripts is further confirmed by results of the EST analysis (Table I).

Figure 2.

GmHop transcript expression in different organs of soybean. RT-PCR showing expression of GmHop transcripts in soybean cotyledons (C), epicotyls (E), hypocotyls (H), first leaves (L1), young leaves (L), shoots (S), and flowers (F). A 388-bp RT-PCR product (bottom band) was obtained using GmHop forward and reverse primers for PCR. The levels of constitutively expressed actin were assayed as controls (675-bp RT-PCR product). In the negative RT-PCR control (B), RT was omitted.

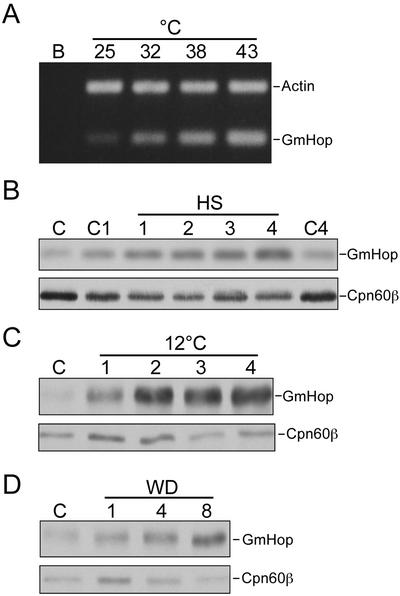

Stress-Inducible Expression of GmHop

A feature shared by Hop homologs of different origin is their stress-inducible expression. We determined GmHop transcript levels in soybean leaves exposed to 25°C, 32°C, 38°C, or 43°C for 2 h (Fig. 3A). The constitutively expressed gene encoding actin served as an internal standard in the RT-PCR assay. The GmHop transcripts were at low levels under the normal growth temperature of 25°C, but accumulated consistently with increasing temperatures. Maximum accumulation was seen after exposure to 43°C. The influence of heat treatment on GmHop protein levels was also investigated. Soybean leaves were exposed to 40°C for 1, 2, 3, and 4 h, and the changes in GmHop levels were detected by western blotting. GmHop protein levels increased above control levels up to the 4-h maximum exposure time (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Stress-inducible expression of GmHop. A, Soybean leaves were exposed to 25°C, 32°C, 38°C, or 43°C for 2 h. RNA was isolated from the leaves and analyzed by RT-PCR. In the negative RT-PCR control (B), RT was omitted. B, Soybean leaves were heat shocked (HS) at 40°C for 1, 2, 3, and 4 h. Leaves from control plants at 25°C were either collected and immediately frozen (C), or first submerged in buffer and maintained at 25°C for 1 h (C1) or 4 h (C4). GmHop and Cpn60-β were detected in whole-cell lysates of the leaves by western blotting. C, Seven-day-old soybean plants were exposed to 12°C for 1, 2, 3, or 4 d. Leaves from control plants at 25°C (C) were collected at the time of transferring other plants to 12°C. GmHop and Cpn60-β were detected by western blotting in whole-cell lysates of leaves collected from these plants. D, First leaves of 2-week-old soybean plants were scored with a razor blade and samples were collected at 1, 4, and 8 h after wounding (WD). Unwounded leaves (C) were collected at the time when wounding was initiated in other leaves. GmHop and Cpn60-β were detected in whole-cell lysates of these leaves by western blotting.

In plants, transcripts of both hsp70 and hsp90 accumulate in response to cold temperature stress (Neven et al., 1992; Krishna et al., 1995). Because it is likely that GmHop functions as a cochaperone of hsp90, we determined if the expression of GmHop was similarly affected by low temperature. Soybean seedlings were exposed to 12°C for 1, 2, 3, and 4 d, and the anti-GmHop-1 antibody was used to detect changes in GmHop levels in the leaves of these seedlings. A significant increase in the abundance of GmHop was observed in response to low temperature, and GmHop levels remained high for the duration of the cold treatment (Fig. 3C).

We have observed hsp90 transcript levels to increase in response to wounding of Brassica napus leaves (P. Krishna and M. Sacco, unpublished data). Here, we tested if GmHop accumulates above control levels in response to mechanical wounding. GmHop levels increased after the leaves were scored with a razor blade (Fig. 3D). The expression of Cpn60-β was monitored as a control in western-blot analysis. In contrast to GmHop, the levels of Cpn60-β did not change significantly in response to heat, cold, or wounding stress.

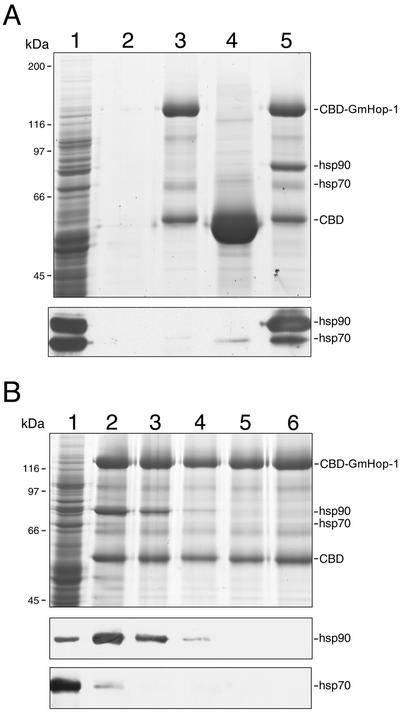

The Recombinant GmHop-1 Binds to Hsp90

For producing large quantities of GmHop-1, and for immobilizing it on a solid support for protein-protein interaction studies, a chitin-binding domain (CBD)-GmHop-1 fusion was created for expression in bacteria. A protein with an approximate molecular mass of 123 kD, the expected size of CBD-GmHop-1, was retained on chitin beads (Fig. 4A, lane 3). Some of the cleaved CBD (55 kD) also remained bound to chitin beads (lane 3). HsHop acts as an organizer protein by binding simultaneously to hsp90 and hsp70 (Chen and Smith, 1998). To begin a functional characterization of GmHop-1, the fusion protein was first immobilized on chitin beads and then incubated with WGL to allow formation of a protein complex. WGL contains relatively high concentrations of hsp90 and hsp70; therefore, it is a good choice for reconstitution studies. After washing of the beads, an abundant protein of approximate molecular mass of 83 kD was detected by Coomassie staining in the CBD-GmHop-1 complex (lane 5). Based on its size, the protein was identified as hsp90 and its identity was confirmed by immunoblotting with an hsp90-specific antibody (Fig. 4A, lane 5, lower). The presence of hsp70 in this complex was not clear in Coomassie-stained gels because a protein of similar size was also present in lane 3, but was confirmed by immunoblot analysis. Incubation of WGL with chitin beads alone (lane 2) or with immobilized CBD affinity tag (lane 4) did not result in the binding of hsp90. Thus, the presence of hsp90 in lane 5 is because of its specific interaction with GmHop-1. In contrast, a low level of hsp70 bound to CBD nonspecifically (lane 4, lower). Because high amounts of CBD were retained on chitin beads (lane 4), it is likely that a small fraction of it was misfolded and, therefore, bound to hsp70.

Figure 4.

GmHop-1 interacts with both hsp90 and hsp70. A, CBD-GmHop-1 immobilized on chitin beads was incubated with wheat germ lysate (WGL). After washing, the proteins were extracted in SDS sample buffer, separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and visualized by Coomassie blue staining. A duplicate gel was blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane and hsp90 and hsp70 were detected using specific antibodies (shown below the stained gel). Lane 1, WGL; lane 2, chitin beads incubated with WGL; lane 3, CBD-GmHop-1 immobilized on chitin beads; lane 4, CBD immobilized on chitin beads and incubated with WGL; lane 5, CBD-GmHop-1 immobilized on chitin beads and incubated with WGL. B, The immobilized CBD-GmHop-1 was incubated with WGL and subsequently washed with HEG (10 mm HEPES [pH 8.0], 1 mm EDTA, 10% [w/v] glycerol, and 50 mm NaCl) buffer containing 50 (lane 2), 200 (lane 3), 300 (lane 4), 400 (lane 5), or 500 (lane 6) mm NaCl. After washing, the proteins were extracted into SDS sample buffer, separated on a SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and visualized by Coomassie blue staining. Duplicate gels were blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes and hsp90 and hsp70 were detected using specific antibodies. WGL (lane 1).

To determine the strength of the interactions of GmHop-1 with hsp90 and hsp70, complexes formed by incubation of immobilized CBD-GmHop-1 with WGL were washed with HEG buffer containing increasing concentrations of NaCl (Fig. 4B). Washing with 200 mm NaCl reduced the amount of hsp90 in the complex (lane 3), and washing with 300 mm NaCl almost completely disrupted the interaction between GmHop-1 and hsp90 (lane 4). Nearly all hsp70 was washed away with 200 mm NaCl (lane 3).

GmHop-1 Binds to Hsp90 via TPR Domains

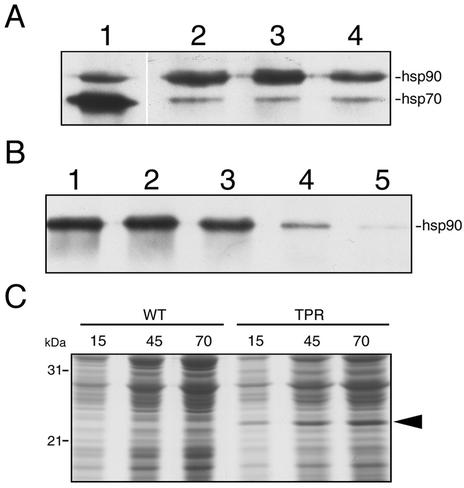

Human Hop has been shown to bind hsp90 and hsp70 via distinct TPR regions (Chen et al., 1996b). Because GmHop-1 contains several potential TPR motifs, it is possible that it too binds hsp90 and hsp70 through its TPR motifs. To determine this, WGL was pre-incubated on ice (Fig. 5A) or at 30°C (Fig. 5B) with either wild-type insect cell lysate or with lysate of insect cells expressing the TPR domain of rat (Rattus norvegicus) protein phosphatase 5 (PP5) before incubation with immobilized CBD-GmHop-1. Pre-incubation of WGL with wild-type insect cell lysate on ice did not affect the binding of hsp90 to GmHop-1 (Fig. 5A, compare lanes 2 and 3). Pre-incubation of WGL with lysate of insect cells expressing the TPR domain of PP5 only slightly decreased hsp90 binding and did not appear to affect hsp70 binding (Fig. 5A, compare lanes 2 and 4). When WGL was pre-incubated with wild-type insect cell lysate at 30°C, the interaction of CBD-GmHop-1 with hsp90 was not affected (Fig. 5B, compare lanes 2 and 3 with 1). However, pre-incubation at 30°C of WGL with increasing amounts of lysate of insect cells expressing the TPR domain of PP5 eliminated hsp90 from the complex (Fig. 5B, compare lanes 4 and 5 with 1). Hsp70 was not detected in any of the samples when pre-incubation was at 30°C (Fig. 5B, lanes 1–5). These results indicate that the binding of GmHop-1 to hsp90 occurs via its TPR domain.

Figure 5.

GmHop-1 interacts with hsp90 via TPR domains. A, WGL was incubated with insect cell lysate on ice before incubation with CBD-GmHop-1. Lane 1, WGL; lane 2, WGL incubated with immobilized CBD-GmHop-1; lanes 3 and 4, WGL incubated with 40 μL of wild-type insect cell lysate (lane 3), or with 40 μL of lysate of insect cells expressing the TPR domain of PP5 (lane 4). B, WGL was incubated with insect cell lysates at 30°C before incubation with CBD-GmHop-1. Lane 1, CBD-GmHop-1 incubated with WGL; lanes 2 through 5, WGL incubated at 30°C with either 20 (lane 2) or 40 (lane 3) μL of wild-type insect cell lysate or with 20 (lane 4) or 40 (lane 5) μL of insect cell lysate expressing the TPR domain of PP5 before incubation with CBD-GmHop-1. Proteins were extracted into SDS sample buffer and separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels before transfer to nitrocellulose membranes. Hsp90 and hsp70 were detected using specific antibodies. C, Aliquots of insect cell lysate (15, 45, and 70 μg of protein) without the TPR domain (WT) and with the TPR domain (TPR) were electrophoresed on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were visualized by Coomassie blue staining. The arrowhead indicates the expressed TPR domain of PP5 within insect cell lysate.

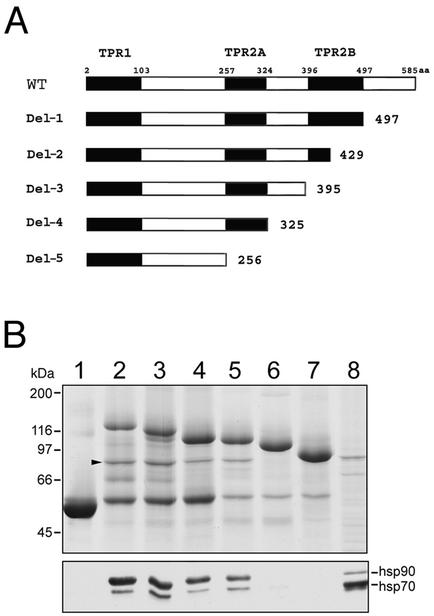

Next, we identified the specific region of GmHop-1 that is necessary for interaction with hsp90. Deletion mutants of GmHop-1 were designed to delineate whether the binding to hsp90 was with the TPR2A region located in the middle of the protein or the TPR2B region located close to the C-terminal end. Diagrams of the deleted proteins are shown in Figure 6A. Deletion mutant 1 (Del-1) was not affected in its binding to hsp90 (Fig. 6B, lane 3) as compared with wild-type GmHop-1 (lane 2). Deletion mutants 2 (lane 4) and 3 (lane 5) showed slight reduction in their abilities to bind hsp90, and deletion mutants 4 (lane 6) and 5 (lane 7) failed to bind hsp90. These results indicate that the region between residues 325 and 395 is essential for the binding of GmHop-1 to hsp90.

Figure 6.

Hsp90 binding to mutant forms of GmHop-1. A, Diagram showing constructs of GmHop-1 that were truncated from the C terminus. The location of TPR regions is depicted. The numbers correspond to the last amino acid of the proteins. B, CBD-GmHop-1, wild-type or mutant forms, were immobilized on chitin beads and incubated with WGL. After washing, the proteins were extracted in SDS sample buffer, separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and visualized by Coomassie blue staining. The arrowhead indicates hsp90. A duplicate gel was blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane and hsp90 and hsp70 were detected using specific antibodies (shown below the stained gel). Lane 1, Immobilized CBD incubated with WGL; lane 2, CBD-GmHop-1 incubated with WGL; lanes 3 through 7, Deletion proteins 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 incubated with WGL; Lane 8, WGL.

GmHop-1 Is Effective in Receptor Reconstitution Assay

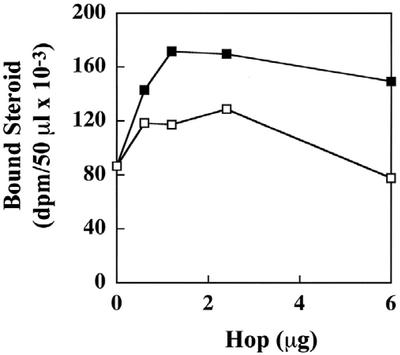

The folding of animal SRs into a functional (steroid-binding) heterocomplex with hsp90 has provided a useful assay for identifying functional relationships between different components of the chaperone machinery. GR can be converted to the steroid- binding state in the presence of five purified proteins (hsp90, hsp70, hsp40/Ydj1p, Hop, and p23), referred to as a minimal folding system (Dittmar et al., 1998). We wished to know if GmHop-1 is functionally active in folding the GR, and if so, how it compares with its animal counterpart. For these experiments, stripped GR was incubated with the minimal folding system consisting of purified rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) hsp90 and hsp70, yeast Ydj1p, and human p23, and increasing concentrations of either purified recombinant GmHop-1 or purified HsHop. As can be seen in Figure 7, GmHop-1 (white squares) was able to potentiate the steroid binding activity of the receptor when used in combination with four purified proteins of animal and yeast origin, but was less effective than HsHop (black squares). GmHop-1 inhibited steroid binding at higher concentrations. This has also been observed with HsHop (Dittmar et al., 1996). These results indicate that the bacterially expressed GmHop-1 is active and most likely functions in a manner similar to animal Hop by bringing hsp90 and hsp70 into a complex to facilitate GR folding. The results also indicate that GmHop-1 can partially substitute for human Hop in the folding assay and that it is able to interact with the mammalian proteins.

Figure 7.

GmHop-1 stimulates GR folding in the purified five protein system. Stripped GR was incubated for 15 min at 30°C with purified rabbit hsp90 and hsp70, human p23, and yeast Ydj1p, and the indicated amounts of purified human Hop (black squares) or GmHop-1 (white squares) in the presence of 100 mm KCl and an ATP-regenerating system. The immune pellets were washed and then assayed for steroid binding. The results are the mean of two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Notwithstanding the importance of hsp90 in numerous cellular processes, including protein folding (Frydman, 2001), genomic silencing (Rutherford and Lindquist, 1998; Csermely, 2001), protein degradation (McClellan and Frydman, 2001), and protein trafficking (Pratt et al., 2001), our understanding of hsp90 in plants remains relatively limited. Reducing hsp90 function in Arabidopsis through treatment with the hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin produced an array of morphological phenotypes, presumably because of release of genetic variation that is normally buffered by hsp90 (Queitsch et al., 2002). Thus, it appears that hsp90 also chaperones the signaling proteins in plants that control plant growth and development. Hsp90 acts in cooperation with other molecular chaperones to carry out its functions, and although it appears that the majority of these chaperones are also present in plants, there is a need to characterize these proteins within the framework of the plant hsp90 chaperone system that has evolved unique characteristics. For example, sodium molybdate stabilizes animal and yeast hsp90 heterocomplexes, but has no effect on plant hsp90 (Dittmar et al., 1997), and the effect of geldanamycin on plant hsp90 is temperature dependent, contrary to its effect on animal hsp90 that is the same at either 0°C or 30°C (Owens-Grillo et al., 1996). Furthermore, in contrast to animals and yeast, some cochaperones of hsp90 in plants are not functional under normal growing conditions and others cannot be detected based on sequence comparisons (P. Krishna, unpublished data). Thus, it is important to identify and independently characterize the proteins that associate with hsp90 in plant cells because assumptions based upon sequence similarities may be misleading or erroneous.

We set out to study a Hop homolog in plants for two reasons: (a) since the isolation of a soybean cDNA with similarity to ScHop (Torres et al., 1995), no further reports on this protein have appeared; and (b) to further characterize the plant system, cDNAs encoding each of the cochaperones, purified proteins, specific antibodies, and sufficient knowledge of each of the cochaperones are required. Sequence analysis of soybean ESTs encoding Hop-like proteins identified two closely related genes, GmHop-1 and -2. The previously identified gene GMSTI likely represents a third gene (GmHop-3) and because soybean is an allotetraploid, yet another gene (GmHop-4) closely related to GmHop-3 may also exist. Thus, Hop-like proteins in soybean appear to be encoded by a multigene family. The Arabidopsis genome sequence has also been examined for Hop-like sequences, and three genes encoding Hop-like proteins (pair-wise sequence identities between these proteins are 82%, 75%, and 74%) were identified (Krishna and Gloor, 2001), confirming the presence of a multigene family for this protein in plants.

Both RT-PCR (Fig. 2) and EST analyses (Table I) confirmed the expression of GmHop transcripts in different organs of soybean. GmHop transcript levels increased after exposure of leaves or whole seedlings to heat, cold, and wounding stress (Fig. 3). The induction of Hop gene expression in response to stress is also common to other organisms. Genes encoding yeast and murine Hop are heat inducible (Nicolet and Craig, 1989; Lässle et al., 1997). The expression of HsHop is up-regulated upon viral transformation (Honoré et al., 1992), and the expression of murine and hamster Hop mRNA is increased as part of the macrophage stress response to lipopolysaccharide (Heine et al., 1999). The stress-induced expression of GmHop is likely linked with hsp90 functions during stress, although this link remains to be demonstrated experimentally.

Hop forms a complex between hsp90 and hsp70 that, together with hsp40/Ydj1p, acts as a machinery to generate steroid-binding activity in SRs (Dittmar et al., 1998). The results of Figure 4 indicate that GmHop-1 binds to both hsp90 and hsp70, although clearly hsp90 is the major protein bound to CBD-GmHop-1 (Fig. 4A, lane 5). If GmHop-1, like its animal counterpart, binds hsp70 via its N terminus TPR domain, then the CBD affinity tag present on the N-terminal end of recombinant GmHop-1 is likely to interfere with this binding. It is possible that the binding of hsp70 to the fusion protein does not represent the total extent of interaction between the two proteins. The salt sensitivity of the hsp70-GmHop-1 association suggests that the interaction is authentic and that the presence of hsp70 is not because of nonspecific binding of hsp70 to either the fusion protein or the chitin beads. We have recently identified a 70-kD protein in wheat as a Hop homolog, which co-immunoprecipitates with hsp90 and hsp70 (P. Krishna and K.C. Kanelakis, unpublished data). This further attests to the notion that the plant Hop-like protein binds to both hsp90 and hsp70. However, because of the weak binding of hsp70 to CBD-GmHop-1, it is not clear whether GmHop-1 functions with hsp70 in a manner similar to its animal counterpart.

The importance of TPR domains in the binding of Hop to hsp90 and hsp70 is well established (Chen et al., 1996b; Blatch and Lässle, 1999). We extrapolate from studies involving competition with the TPR domain of PP5 (Fig. 5) that GmHop-1 binds to hsp90 via its TPR domain. The temperature-dependent competition by the TPR domain may be because of a change in the nucleotide-bound state of hsp90 or a slight conformational change in hsp90 at 30°C that promotes its interaction with the expressed TPR domain. The end result was a loss in hsp90 binding to GmHop-1 because of competition by the TPR domain of PP5 for binding to hsp90. The reason why hsp70 binding was eliminated by pre-incubation of WGL at 30°C is presently not clear. A change in the nucleotide-bound state of hsp70 at 30°C could be an underlying cause.

GmHop-1, similar to its animal counterpart, contains three TPR regions and could bind to hsp90 via its central TPR region, referred to as the TPR2A domain in HsHop (Scheufler et al., 2000). The TPR region located in the C-terminal end of HsHop, referred to as TPR2B (Scheufler et al., 2000), contains a perfectly conserved hexamer YSNRAA (Fig. 1). Substitution and deletion of this sequence in HsHop compromised hsp90 binding but did not completely eliminate it (Chen and Smith, 1998). Deletion 2 of GmHop-1 lacks this sequence and had less hsp90 bound to it (Fig. 6B, lane 4), but the reduction in hsp90 binding was not as drastic as in the case of human Hop. Because the deletion of the conserved hexamer does not ablate the binding of hsp90, it is likely that a ligand for TPR2B is yet to be identified. Although a TPR motif was not identified between amino acids 325 through 395, deletion mutant 4 was found to lack hsp90-binding activity (lane 6). Residues within this region that are important for contacts with hsp90 have been identified in HsHop (Scheufler et al., 2000). A subset of these residues is also conserved in GmHop-1 (Fig. 1). This provides further confirmation that the region 325 through 395 is required for hsp90 binding. Mutational studies of HsHop revealed that maximal binding of hsp70 to Hop occurs when Hop is bound to hsp90 (Chen and Smith, 1998). Furthermore, C-terminal truncations of HsHop beyond amino acid 431 failed to bind hsp70 (Chen et al., 1996b). Thus, the lack of hsp70 in complexes of deletions 4 and 5 (Fig. 6B, lanes 6 and 7) is not surprising. In studies with HsHop, it was also found that the DPEV and DPAM sites located in the C-terminal end of this protein contribute to hsp70 binding (Chen and Smith, 1998). These sites are partially conserved in GmHop-1, but deletion of these sites did not result in any significant reduction of hsp70 binding to the mutant (Fig. 6B, lane 3). In comparison, mutation of either one of the two sites in HsHop caused a 50% reduction in the binding of the mutant protein to hsp70 (Chen and Smith, 1998). Conservation of the function of GmHop-1 in acting as an organizing protein and/or as a regulator of hsp90 function is apparent from the results of Figure 7. GmHop-1 could stimulate steroid-binding activity of the GR in a five-protein assembly system, albeit at a lower level than HsHop. Because three other components of this system were of animal origin, it is not surprising that the effect produced by GmHop-1 was lower than that produced by HsHop.

Taken together, the results of the present study indicate that the general characteristics of plant Hop are similar to animal and yeast Hop and that the plant Hop may be a general cochaperone of hsp90. The functions of plant Hop in the context of hsp90 client proteins will become evident only when the client proteins of plant hsp90 have been identified. We have identified previously three components of the plant hsp90 chaperone complex: hsp90, hsp70, and the high-Mr immunophilins (Owens-Grillo et al., 1996; Stancato et al., 1996; Reddy et al., 1998). We now add plant Hop to this list. With this background knowledge of GmHop-1, the availability of GmHop-1 cDNA and the possibility of preparing purified protein, in conjunction with similar possibilities for other components of the complex, we can begin to probe the mechanistic details of the hsp90 chaperone complex in plants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and Sequence Analysis of GmHop-1 cDNA

A collection of 2,000 ESTs from a soybean (Glycine max) seed coat cDNA library (Gijzen, 1997) was initially searched for transcripts encoding ScHop-like proteins by TBLASTN analysis (Altschul et al., 1990). A full-length cDNA encoding GmHop-1 was sequenced on both strands by dye termination chemistry using a series of synthetic oligonucleotide primers. DNA and deduced amino acid sequences were analyzed using BLAST. Protein domains within GmHop-1 were predicted using ProfileScan provided by the Swiss Institute for Experimental Cancer Research (Lausanne, Switzerland). Later, nucleotide sequences of GmHop-1 and GmHop-3 were used to search soybean ESTs in current GenBank dbEST releases (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) by BLASTN analysis. Highly significant matches were analyzed using an assembly and alignment program (Seq-Man, Lasergene, DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI) and ESTs were distinguished from one another and grouped according to organ distribution.

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Soybean cv Harosoy 63 plants were grown in a growth chamber maintained at 25°C with a 12-h photoperiod. The light intensity was 150 μE m−2 s−1. Cotyledons, hypocotyl, epicotyl, first leaves, and shoots were collected from 7-d-old plants. Young leaves and flowers were harvested from 6-week-old plants. All plant material was frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after collection and stored at −80°C.

For heat stress, leaves from 14-d-old plants grown at 25°C were submerged in 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and exposed to 25°C, 32°C, 38°C, or 43°C for 2 h. After stress treatment, leaves were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. For cold stress, 7-d-old plants grown at 25°C were transferred to a growth chamber maintained at 12°C for a maximum of 4 d. Leaves were collected daily from plants kept at 12°C, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Leaves from control plants were collected at the time of transferring plants to 12°C. For wounding stress, first leaves of 14-d-old plants grown at 25°C were scored with a razor blade and left attached to the plant. Control leaves were collected from a separate plant at this time. Scored leaves were collected 1, 4, and 8 h after wounding, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from frozen material according to the method of Chomezynski and Sacchi (1987). RNA (2 μg) was reverse transcribed using the oligo(dT)18 primer and Super Script First Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). PCR was carried out with an initial denaturation step of 94°C for 2 min followed by 28 cycles of denaturation (15 s at 94°C), annealing (30 s at 58°C), and extension (1 min at 68°C). After the last cycle, a final extension was carried out for 10 min at 68°C. PCR products were visualized on 1.2% (w/v) agarose gels using a UV light transilluminator. For analysis of transcripts in soybean organs, PCR was performed for 28 cycles for both GmHop and actin. For analysis of transcripts in heat-shocked material, PCR was performed for 23 cycles for GmHop and 28 cycles for actin. The following primers were used: GmHop, forward, 5′ GAAAAGGAAGCGGGCAAT 3′; GmHop, reverse, 5′ CTTGCTGTTCTAGTTCTTTCTTC 3′; actin, forward, 5′ ACGAGCCCTAGCATTGTGG 3′; and actin, reverse, 5′ AACCGTCCCGCACCGATA 3′.

Construction of a Recombinant GmHop-1

To fuse the CBD affinity tag on the N terminus of GmHop-1 to prepare the CBD-GmHop-1 fusion protein, the coding region of GmHop-1 was cloned in frame with CBD in the pTYB12 expression vector (New England Biolabs Ltd., Pickering, ON, Canada). The GmHop-1 cDNA was amplified by PCR using a forward primer (5′ AAAA CAT ATG GGC GAC GAA GCC AAA GC 3′) to create an NdeI site at the ATG start site, and a reverse primer (5′ AAAA CCC GGG CTT CAT CTG GAC AAT TCC AGC 3′) to create an SmaI site at the 3′ end of the GmHop-1 coding region. The restriction sites in the primers are underlined. PCR was performed using Pfu (Pyrococcus furiosus) DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The purified PCR product was cloned into the SmaI site of pBluescript SKII to give pGm1. The coding region was excised by digestion with NdeI and SmaI and directionally cloned into pTYB12 to produce pGm2. The DNA sequence of the open reading frame was verified by sequencing.

Construction of GmHop-1 Mutants

To prepare deletion mutants of GmHop-1, the GmHop-1 cDNA was amplified by PCR using the forward primer (5′ AAAA CAT ATG GGC GAC GAA GCC AAA GC 3′) in combination with five different reverse primers (primer 1, 5′ AA CCC GGG TTA GTT GTT AGA GTC ATA TTT C 3′; primer 2, 5′ AA CCC GGG TTA ATC TTT TGG ATT TCT TCG 3′; primer 3, 5′ AA CCC GGG TTA CAA CTT TGG ATC AAA ATA TTC 3′; primer 4, 5′ AA CCC GGG TTA TCT TAG TTC TCT TCC TCT TTC 3′; and primer 5, 5′ AA CCC GGG TTA CTC AGC CTT CTT CTG CTC TGC 3′). The cloning strategy for each of the deletion constructs was as described for pGm1 and pGm2.

Expression of Recombinant Proteins

The expression constructs were introduced into Escherichia coli strain ER2566 cells. Bacteria from a fresh colony were grown overnight at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium containing 100 μg mL−1 ampicillin. An aliquot of the overnight culture was used to inoculate 20 mL of fresh Luria-Bertani containing ampicillin and the culture was grown at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.5 to 0.6. At this time, isopropylthio-β-galactoside was added at a final concentration of 0.3 mm to induce expression of the fusion protein CBD-GmHop-1. The culture was grown for an additional 4.5 h at 30°C. Bacterial cells were pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in HEG buffer (10 mm HEPES [pH 8.0], 1 mm EDTA, 10% [w/v] glycerol, and 50 mm NaCl), and lysed by sonication on ice. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 12,000g for 30 min at 4°C. The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad Ltd., Mississauga, ON, Canada).

Affinity Purification of CBD-GmHop-1 and Interacting Proteins

Total protein extract (200 μL at a protein concentration of approximately 4.5 mg mL−1) prepared from an induced bacterial culture was incubated with 50 μL (bed volume) of chitin beads to immobilize the fusion protein. The beads were washed three times with 1 mL of HEG buffer and then incubated with 50 μL of WGL (Promega, Madison, WI) on ice for 1 h. The beads were washed five times with 1 mL of HEG buffer containing either 50, 200, 300, 400, or 500 mm NaCl. Proteins retained on the chitin beads were extracted into SDS sample buffer by boiling for 2 min and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific to hsp90 and hsp70.

To compete GmHop-1 binding to hsp90 with the TPR domain, 800 μL of total protein extract was incubated with 300 μL of chitin beads. After three washes with 1 mL of HEG buffer, the chitin beads were dispensed into five 50-μL aliquots. Aliquots of WGL were incubated with either 20 or 40 μL of wild-type insect cell lysate or lysate of insect cells expressing the TPR domain of rat (Rattus norvegicus) PP5 (Chen et al., 1996a) for 1 h either on ice or at 30°C, before incubation on ice with the immobilized CBD-GmHop-1 fusion protein. For controls, an equal volume of WGL supplemented with buffer was incubated either on ice or at 30°C before incubation with immobilized CBD-GmHop-1. The beads were washed with 30 volumes of HEG buffer to remove any unbound proteins. Bound proteins were extracted in sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Preparation of Soybean Whole-Cell Lysates

Frozen plant material was ground using a pestle and mortar in extraction buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mm EDTA [pH 8.0], 20 mm NaCl, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mm benzamidine, 1 μg mL−1 leupeptin, and 2 μg mL−1 aprotinin). The homogenate was centrifuged twice at 13,000 rpm for 30 min in an Eppendorf centrifuge (Eppendorf Scientific, Westbury, NY) at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad). Protein samples were aliquoted and an equal volume of 2× SDS-sample buffer (0.125 m Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 4% [w/v] SDS, 20% [w/v] glycerol, 0.004% [w/v] bromphenol blue, and 5% [v/v] β-mercaptoethanol) was added before storage at −20°C.

Protein Purification

Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) hsp90 and hsp70 were purified as described previously by Hutchison et al. (1994), human (Homo sapiens) p23 was purified as described by Johnson and Toft (1994), yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) Ydj1p was purified according to Dittmar et al. (1998), and the purification of human Hop was as described by Morishima et al. (2000). For purification of GmHop-1, the CBD-GmHop-1 was immobilized on chitin beads and after washing with HEG, cleavage was induced by resuspending the beads in three bed volumes of cleavage buffer (20 mm HEPES [pH 8.0], 50 mm NaCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, and 50 mm dithiothreitol). Excess cleavage buffer was removed immediately after resuspension and the beads were left overnight at 20°C. Cleaved GmHop-1 was eluted sequentially with HEG buffer in two 1-mL fractions and then dialyzed against HKD (10 mm HEPES [pH 7.4], 100 mm KCl, and 5 mm dithiothreitol) buffer. The concentration and purity of GmHop-1 was assessed by the Bradford method and SDS-PAGE, respectively.

Antibody Generation

Before immunization, the rabbit was bled to collect pre-immune serum. A purified preparation of GmHop-1 (750 μg) was mixed 1:1 (v/v) with Freund's complete adjuvant (Invitrogen) and injected into the rabbit. An additional injection with 500 μg of protein mixed with incomplete Freund's adjuvant was done after 2 weeks. Antiserum was collected 3 weeks after the second injection with the antigen. The antiserum cross-reacted with purified GmHop-1 and specifically recognized a protein with an approximate molecular mass of 70 kD in soybean whole-cell lysates. No cross-reaction was obtained with the pre-immune serum, even at a dilution of 1:2,000 (v/v).

Detection of Proteins by Western Blotting

Proteins were separated on 7.5% (w/v) SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes by electroblotting using a Trans-Blot Semi-Dry Electrophoretic Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad). GmHop was detected using the anti-GmHop-1 antibody at a dilution of 1:5,000 (v/v) and Cpn60-β was detected with an anti-Cpn60-β antibody (provided by Sean M. Hemmingsen, Plant Biotechnology Institute, Saskatoon, SK, Canada) at a dilution of 1:500 (v/v). Hsp90 and hsp70 were detected using the R2 anti-hsp90 antibody (Krishna et al., 1997) and an anti-hsp70 antibody (provided by Dr. Elizabeth Vierling, University of Arizona, Tuscon), respectively, each at a dilution of 1:7,000 (v/v). The peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG was used at a dilution of 1:5,000 (v/v). The antigen-antibody complexes were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (ECL system, Amersham Biosciences, Baie d'Urfé, QC, Canada).

Receptor Reconstitution Assay

Mouse (Mus musculus) GR was expressed in Sf9 cells and immuno-adsorbed from 50-μL aliquots of Sf9 cytosol with 14 μL of protein A-Sepharose precoupled to 7 μL of FiGR (mouse monoclonal IgG2b to GR) ascites (Morishima et al., 2000). Immuno-adsorbed receptors were stripped of associated proteins by incubating the immunopellet for 2 h at 4°C with 0.5 m NaCl in TEG (10 mm TES [pH 7.6], 50 mm NaCl, 4 mm EDTA, and 10% [w/v] glycerol). The pellets were washed once with 1 mL of TEG followed by a second wash with 1 mL of HEPES buffer (10 mm HEPES [pH 7.35]). The stripped receptor was incubated with the five-protein assembly system (20 μg of purified rabbit hsp90, 15 μg of purified rabbit hsp70, 6 μg of purified human p23, 0.4 μg of purified yeast Ydj1p, and the indicated amounts of purified human Hop or GmHop-1) and adjusted to 50 μL with HKD buffer (10 mm HEPES [pH 7.4], 100 mm KCl, and 5 mm dithiothreitol) containing 20 mm sodium molybdate and 5 μL of an ATP-regenerating system (50 mm ATP, 250 mm creatine phosphate, 20 mm magnesium acetate, and 100 units mL−1 creatine phosphokinase). The assay mixtures were incubated for 15 min at 30°C with suspension of the pellets by shaking the tubes every 2 min, and at the end of the incubation, the pellets were washed twice with 1 mL of ice-cold TEGM buffer (TEG with 20 mm sodium molybdate). The immune pellets were assayed for steroid binding by incubating overnight at 4°C in 50 μL of HEM buffer (10 mm HEPES [pH 7.4], 1 mm EDTA, and 20 mm sodium molybdate) plus 50 nm [3H]triamcinolone acetonide (PerkinElmer Life Sciences Inc., Boston). Samples were washed three times with 1 mL of TEGM and counted by liquid scintillation spectrometry. The steroid binding is expressed as dpm of [3H]triamcinolone acetonide-bound/FiGR (mouse monoclonal IgG2b to GR) immunopellet prepared from 50 μL of Sf9 cytosol.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Sean Hemmingsen and Elizabeth Vierling for providing anti-Cpn60-β and anti-hsp70 antibodies, respectively; Dr. Michael Chinkers for insect cells overexpressing the TPR domain of PP5; Dr. Sangeeta Dhaubhadel for primers specific to soybean actin; Professor Mark Perry for helpful suggestions on the manuscript; Dr. Andre Lachance for carefully reading the manuscript; and Zezhou Wang for help with the figures.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (research grant to P.K.).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.011940.

LITERATURE CITED

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatch GL, Lässle M. The tetratricopeptide repeat: a structural motif mediating protein-protein interactions. BioEssays. 1999;21:932–939. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199911)21:11<932::AID-BIES5>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatch GL, Lässle M, Zetter BR, Kundra V. Isolation of a mouse cDNA encoding mSTI1, a stress-inducible protein containing the TPR motif. Gene. 1997;194:277–282. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchner J. Hsp90 & Co.: a holding for folding. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:136–141. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01373-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H-CJ, Nathan DF, Lindquist S. In vivo analysis of the Hsp90 co-chaperone Sti1 (p60) Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:318–325. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M-S, Silverstein AM, Pratt WB, Chinkers M. The tetratricopeptide repeat domain of protein phosphatase 5 mediates binding to glucocorticoid receptor heterocomplexes and acts as a dominant negative mutant. J Biol Chem. 1996a;271:32315–32320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Prapapanich V, Rimerman RA, Honoré B, Smith DF. Interactions of p60, a mediator of progesterone receptor assembly, with heat shock proteins Hsp90 and Hsp70. Mol Endocrinol. 1996b;10:682–693. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.6.8776728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Smith DF. Hop as an adaptor in the heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) and Hsp90 chaperone machinery. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:35194–35200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.35194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung J, Smith DF. Molecular chaperone interactions with steroid receptors: an update. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:939–946. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.7.0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomezynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csermely P. Chaperone overload is a possible contributor to “civilization diseases.”. Trends Genet. 2001;17:701–704. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02495-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar KD, Banach M, Galigniana MD, Pratt WB. The role of DnaJ-like proteins in glucocorticoid receptor.hsp90 heterocomplex assembly by the reconstituted hsp90.p60.hsp70 foldosome complex. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7358–7366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar KD, Demady DR, Stancato LF, Krishna P, Pratt WB. Folding of the glucocorticoid receptor by the heat shock protein (hsp) 90-based chaperone machinery. The role of p23 is to stabilize receptor.hsp90 heterocomplexes formed by hsp90.p60.hsp70. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21213–21220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar KD, Hutchison KA, Owens-Grillo JK, Pratt WB. Reconstitution of the steroid receptor · hsp90 heterocomplex assembly system of rabbit reticulocyte lysate. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12833–12839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolinski KJ, Cardenas ME, Heitman J. CNSI encodes an essential p60/sti1 homolog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that suppresses cyclophilin 40 mutations and interacts with hsp90. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7344–7352. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman J. Folding of newly translated proteins in vivo: the role of molecular chaperones. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:603–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijzen M. A deletion mutation at the ep locus causes low seed coat peroxidase activity in soybean. Plant J. 1997;12:991–998. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.12050991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine H, Delude RL, Monks BG, Espevik T, Golenbock DT. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide induces expression of the stress response genes hop and H411. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21049–21055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honoré B, Leffers H, Madsen P, Rasmussen HH, Vandekerckhove J, Celis JE. Molecular cloning and expression of a transformation-sensitive human protein containing the TPR motif and sharing identity to the stress-inducible yeast protein STI1. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:8485–8491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison KA, Dittmar KD, Pratt WB. All of the factors required for assembly of the glucocorticoid receptor into a functional heterocomplex with heat shock protein 90 are pre-associated in a self-sufficient protein folding structure. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27894–27899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hymowitz T, Singh RJ. Taxonomy and speciation. In: Wilcox JR, editor. Soybeans: Improvement, Production, and Uses. Ed 2. Madison, WI: American Society of Agronomy; 1987. pp. 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Schumacher RJ, Ross ED, Toft DO. Hop modulates hsp70/hsp90 interactions in protein folding. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3679–3686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Corbisier R, Stensgard B, Toft DO. The involvement of p23, hsp90, and immunophilins in the assembly of progesterone receptor complexes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;56:31–37. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Toft DO. A novel chaperone complex for steroid receptors involving heat shock proteins, immunophilins, and p23. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24989–24993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna P, Gloor G. The Hsp90 family of proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2001;6:238–246. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2001)006<0238:thfopi>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna P, Reddy RK, Sacco M, Frappier JR, Felsheim RF. Analysis of the native forms of the 90 kDa heat shock protein (hsp90) in plant cytosolic extracts. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;33:457–466. doi: 10.1023/a:1005709308096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna P, Sacco M, Cherutti JF, Hill S. Cold-induced accumulation of hsp90 transcripts in Brassica napus. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:915–923. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.3.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lässle M, Blatch GL, Kundra V, Takatori T, Zetter BR. Stress-inducible, murine protein mSTI1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1876–1884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JA, Kalton HM, Gaber RF. Cns1 is an essential protein associated with the hsp90 chaperone complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that can restore cyclophilin 40-dependent functions in cpr7Δ cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7353–7359. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan AJ, Frydman J. Molecular chaperones and the art of recognizing a lost cause. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:E51–E53. doi: 10.1038/35055162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishima Y, Kanelakis KC, Silverstein AM, Dittmar KD, Estrada L, Pratt WB. The hsp organizer protein Hop enhances the rate of but is not essential for glucocorticoid receptor folding by the multiprotein hsp90-based chaperone system. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6894–6900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.6894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neven LG, Haskell DW, Guy CL, Denslow N, Klein PA, Green LG, Silverman A. Association of 70-kilodalton heat shock cognate proteins with acclimation to cold. Plant Physiol. 1992;99:1362–1369. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.4.1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolet CM, Craig EA. Isolation and characterization of STI1, a stress-inducible gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:3638–3645. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.9.3638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens-Grillo JK, Stancato LF, Hoffmann K, Pratt WB, Krishna P. Binding of immunophilins to the 90 kDa heat shock protein (hsp90) via a tetratricopeptide repeat domain is a conserved protein interaction in plants. Biochemistry. 1996;35:15249–15255. doi: 10.1021/bi9615349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaretou B, Prodromou C, Roe SM, O'Brien R, Ladbury JE, Piper PW, Pearl LH. ATP binding and hydrolysis are essential to the function of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone in vivo. EMBO J. 1998;17:4829–4836. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt WB, Krishna P, Olsen LJ. Hsp90-binding immunophilins in plants: the protein movers. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:54–58. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01843-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt WB, Toft DO. Steroid receptor interactions with heat shock protein and immunophilin chaperones. Endocrinol Rev. 1997;18:306–360. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.3.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodromou C, Siligardi G, O'Brien R, Woolfson D, Regan L, Panaretou B, Ladbury J, Piper P, Pearl L. Regulation of Hsp90 ATPase activity by tetratricopeptide repeat domain co-chaperones. EMBO J. 1999;18:754–762. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queitsch C, Sangster TA, Lindquist S. Hsp90 as a capacitor for phenotypic variation. Nature. 2002;417:618–624. doi: 10.1038/nature749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy RK, Kurek I, Silverstein AM, Chinkers M, Breiman A, Krishna P. High molecular weight FK506-binding proteins are components of heat shock protein 90 heterocomplexes in wheat germ lysate. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:1395–1401. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.4.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford SL, Lindquist S. Hsp90 as a capacitor for morphological evolution. Nature. 1998;396:336–342. doi: 10.1038/24550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheufler C, Brinker A, Bourenkov G, Pegoraro S, Moroder L, Bartunik H, Hartl FU, Moarefi I. Structure of TPR domain-peptide complexes: critical elements in the assembly of the Hsp70-Hsp90 multichaperone machine. Cell. 2000;101:199–210. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80830-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DF, Sullivan WP, Marion TN, Zaitsu K, Madden B, McCormick DJ, Toft DO. Identification of a 60-kilodalton stress-related protein, p60, which interacts with hsp90 and hsp70. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:869–876. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DF, Whitesell L, Nair SC, Chen S, Prapapanich V, Rimerman RA. Progesterone receptor structure and function altered by geldanamycin, an hsp90-binding agent. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6804–6812. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stancato LF, Hutchison KA, Krishna P, Pratt WB. Animal and plant cell lysates share a conserved chaperone system that assembles the glucocorticoid receptor into a functional heterocomplex with hsp90. Biochemistry. 1996;35:554–561. doi: 10.1021/bi9511649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan W, Stensgard B, Caucutt G, Bartha B, McMahon Alnemri ES, Litwack G, Toft DO. Nucleotides and two functional states of hsp90. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8007–8012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.8007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres JH, Chantellard P, Stutz E. Isolation and characterization of Gmsti, a stress-inducible gene from soybean (Glycine max) coding for a protein belonging to the TPR (tetratricopeptide repeats) family. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;27:1221–1226. doi: 10.1007/BF00020896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JC, Moarefi I, Hartl FU. Hsp90: a specialized but essential protein-folding tool. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:267–273. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]