Abstract

Glucosinolates are amino acid-derived natural products that, upon hydrolysis, typically release isothiocyanates with a wide range of biological activities. Glucosinolates play a role in plant defense as attractants and deterrents against herbivores and pathogens. A key step in glucosinolate biosynthesis is the conversion of amino acids to the corresponding aldoximes, which is catalyzed by cytochromes P450 belonging to the CYP79 family. Expression of CYP79D2 from cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz.) in Arabidopsis resulted in the production of valine (Val)- and isoleucine-derived glucosinolates not normally found in this ecotype. The transgenic lines showed no morphological phenotype, and the level of endogenous glucosinolates was not affected. The novel glucosinolates were shown to constitute up to 35% of the total glucosinolate content in mature rosette leaves and up to 48% in old leaves. Furthermore, at increased concentrations of these glucosinolates, the proportion of Val-derived glucosinolates decreased. As the isothiocyanates produced from the Val- and isoleucine-derived glucosinolates are volatile, metabolically engineered plants producing these glucosinolates have acquired novel properties with great potential for improvement of resistance to herbivorous insects and for biofumigation.

Glucosinolates are plant natural products found throughout the Capparales order. Upon tissue disruption, the glucosinolates are hydrolyzed by specific enzymes called myrosinases to produce a wide range of biologically active compounds such as isothiocyanates, nitriles, and thiocyanates (for review, see Halkier, 1999; Rask et al., 2000). In general, glucosinolates and their degradation products play a role in plant defense as deterrents for generalist herbivores and microorganisms and as attractants for specialized insects (for review, see Raybould and Moyes, 2001). In human consumption, certain isothiocyanates are well known flavor compounds, e.g. p-hydroxybenzyl isothiocyanate (yellow mustard, Sinapis alba) and isopropyl isothiocyanate (capers, Capparis spinosa). In addition, several isothiocyanates, especially those from chain-elongated aliphatic sulfinyl glucosinolates and phenylethyl glucosinolate, have been shown to have cancer-preventive properties (for review, see Talalay and Fahey, 2001).

Glucosinolates are derived from a number of amino acids, which include the protein amino acids Ala, Val, Leu, Ile, Met, Phe, Tyr, and Trp as well as chain-elongated derivatives of Met and Phe. Glucosinolate biosynthesis is a three-step process (for review, see Wittstock and Halkier, 2002). First, the amino acid may be taken through the chain elongation pathway, of which the first genes were recently cloned (Campos et al., 2000; Kroymann et al., 2001). Second, the core glucosinolate structure is produced (see below). Third, secondary modifications may take place, which include oxidation, alkenyl formation, hydroxylation, and methoxylation reactions. 2-Oxoglutarate-dependent monooxygenases controlling production of alkenyl- and hydroxyalkyl-glucosinolates have recently been identified (Kliebenstein et al., 2001).

The first committed step in the biosynthesis of the core glucosinolate structure is the conversion of amino acids to the corresponding aldoximes. This reaction is catalyzed by substrate-specific cytochromes P450 from the CYP79 family. The Arabidopsis genome contains seven CYP79 genes, of which five have been characterized with respect to substrate specificity (for review, see Halkier et al., 2002). CYP79A2 converts Phe to phenylacetaldoxime (Wittstock and Halkier, 2000), CYP79B2 and CYP79B3 metabolize Trp (Hull et al., 2000; Mikkelsen et al., 2000), and CYP79F1 and CYP79F2 metabolize all chain-elongated Met derivatives and only long-chain Met derivatives, respectively (Hansen et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2003). Cyanogenic glucosides are another group of natural plant products derived from amino acids and with aldoximes as intermediates. They are evolutionarily related to glucosinolates as CYP79 enzymes catalyze the aldoxime production in both pathways. Several CYP79s from cyanogenic species have been isolated and characterized. These include the Tyr-metabolizing CYP79A1 from Sorghum bicolor (Halkier et al., 1995), the Tyr-metabolizing CYP79E1 and CYP79E2 from Triglochin maritima (Nielsen and Møller, 2000), and the Val- and Ile-metabolizing CYP79D1 and CYP79D2 from cassava (Manihot esculenza Crantz; Andersen et al., 2000).

The substrate-specific CYP79s constitute the first committed step in biosynthesis of protein amino acid-derived glucosinolates. This makes the CYP79 enzymes important tools for modifying glucosinolate profiles (for review, see Mikkelsen et al., 2002). Overexpression of endogenous CYP79s, e.g. CYP79B2 and CYP79A2, have resulted in high accumulation of Trp-derived indole glucosinolates and the Phe-derived benzylglucosinolate, respectively (Mikkelsen et al., 2000; Wittstock and Halkier, 2000). This shows that the CYP79s constituted the rate-limiting step and that the postaldoxime enzymes have a higher capacity for production of glucosinolates than what is required for biosynthesis at physiological levels. The postaldoxime enzymes have previously been shown to have high specificity for the functional groups of later intermediates, but low specificity for the side chain (for review, see Halkier, 1999). This indicates that exogenous aldoximes may be converted to the corresponding glucosinolates as has been shown for 2-nitrobenzaldoxime (Grootwassink et al., 1990) and p-hydroxyphenylacetaldoxime (Bak et al., 1999). In this article, we report metabolic engineering of the two novel Val- and Ile-derived glucosinolates in Arabidopsis expressing CYP79D2 from cassava and we show that this is achieved with no effect on the morphological phenotype or on the accumulation of endogenous glucosinolates.

RESULTS

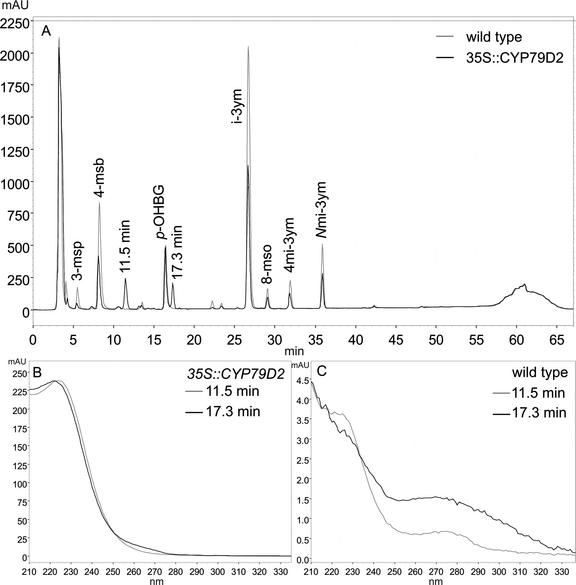

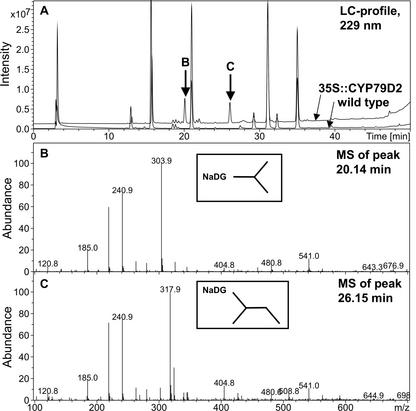

Arabidopsis was transformed with the 35S::CYP79D2 construct by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated DNA transfer. Transformants were selected by plating on gentamycin, and 31 independent T1 lines were identified. The 31 lines exhibited wild-type phenotype on soil, although when germinated on selective medium, growth was slightly retarded, possibly due to the presence of gentamycin. Glucosinolates were extracted from these lines and were analyzed by HPLC and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). The HPLC profile from 35S::CYP79D2 Arabidopsis plants contained two peaks that were not present in the wild type (Fig. 1A). The retention times for the peaks were 11.5 and 17.3 min, respectively, and both peaks had a UV spectrum characteristic of aliphatic glucosinolates (Fig. 1B). The LC profile of glucosinolates extracted from 35S::CYP79D2 Arabidopsis plants contained two peaks at 20.14 min and 26.15 min, respectively, that were not present in the wild-type (Fig. 2A). The mass spectrum of the peak at 20.14 min showed a major m/z of 303.9 corresponding to the sodium salt of the Val-derived desulphoglucosinolate molecular ion (Fig. 2B). Major fragmentary ions of m/z 185, 219, and 241 corresponded to, respectively, the sodium salt of the Glc moiety, the sodium salt of the thio-Glc moiety, and a desulphoglucosinolate structure lacking the amino acid side chain and with the N-C double bond reduced. The mass spectrum of the peak at 26.15 min showed a major m/z of 317.9, corresponding to the molecular ion of the sodium salt of the Ile-derived desulphoglucosinolate (Fig. 2C). A fragmentation pattern similar to that of the peak at 20.14 min was observed. This conclusively demonstrated that the 35S::CYP79D2 Arabidopsis plants produced i-prop and 1Me-prop.

Figure 1.

HPLC analysis of glucosinolates from T1 35S::CYP79D2 Arabidopsis plants. Glucosinolates were extracted from rosette leaves of 4- to 6-week-old Arabidopsis plants grown on selective medium and analyzed by HPLC. A, HPLC profile of glucosinolates extracted from 35S::CYP79D2 and wild-type plants. B, UV spectrum of the novel peaks at 11.5 and 17.3 min found only in 35S::CYP79D2 plants. C, UV spectrum of the wild-type contribution at 11.5 and 17.3 min. 3-msp, 3-Methylsulfinyl glucosinolate; 4-msb, 4-methylsulfinylbutyl glucosinolate; p-OHBG, p-hydroxybenzyl glucosinolate (internal standard); 4-mtb, 4-methylthiobutyl glucosinolate; i-3ym, indol-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate; 8-mso, 8-methylsulfinyloctyl glucosinolate; 4 mi-3ym, 4-methoxyindol-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate; Nmi-3ym, N-methoxyindol-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate.

Figure 2.

LC-MS analysis of glucosinolates in 35S::CYP79D2 Arabidopsis plants. Glucosinolates were extracted from rosette leaves of 4- to 6-week-old Arabidopsis plants and were subjected to LC-MS analysis. A, LC profile at 229 nm. Two distinct peaks with retention times 20.14 and 26.15 min, respectively, were found in 35S::CYP79D2 plants, but not in wild type. B, MS of the peak at 20.14 min. C, MS of the peak at 26.15 min. NaDG, Sodium salt of desulfoglucosinolate.

As standards for i-prop and 1Me-prop, we analyzed the glucosinolate profiles by HPLC and LC-MS of two plant species known to contain predominantly branched aliphatic glucosinolates (Fahey et al., 2001). For Putranjiva roxburghii, the dominant peak in the LC profile had a retention time of 20.14 min, with an m/z of 303.9 corresponding to the sodium salt of the Val-derived desulphoglucosinolate. Using the HPLC system, the corresponding dominant peak had a retention time of 11.5 min. Similar to Capparis flexuosa, the dominant peak in the LC profile had a retention time of 26.15 min, with an m/z of 317.9 corresponding to the sodium salt of the Ile-derived desulphoglucosinolate. Using the HPLC, the corresponding peak had a retention time of 17.3 min. From the data, we concluded that i-prop has a retention time of 11.5 min and that 1Me-prop has a retention time of 17.3 min in the given HPLC system.

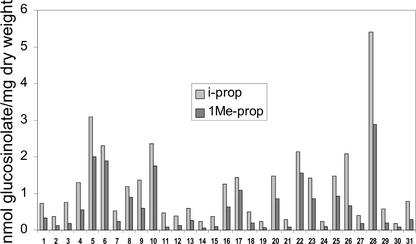

The glucosinolate profiles in 6-week-old rosette leaves of 31 independent T1 lines were analyzed by HPLC and quantified (Fig. 3). Line 28 accumulated the highest quantities of i-prop (5.4 nmol mg−1 dry weight) and 1Me-prop (2.9 nmol mg−1) with a total of 8.2 nmol mg−1. In this line, i-prop and 1Me-prop accounted for approximately 35% of the total glucosinolate content. Other high-expressing lines included lines 5, 6, and 10, which contained, respectively, 5.1, 4.2, and 4.1 nmol mg−1 i-prop plus 1Me-prop. All other lines accumulated lower amounts, and 16 lines contained a total of about 1 nmol mg−1 or less. The data were produced from heterozygous T1 lines. It was expected that the homozygotes would accumulate higher levels of i-prop and 1Me-prop due to increased copy number. However, this was not the case (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Accumulation of i-prop and 1Me-prop in 31 independent 35S::CYP79D2 Arabidopsis lines. Glucosinolates were extracted from 6-week-old rosette leaves of transgenic and wild-type Arabidopsis plants and were analyzed by HPLC.

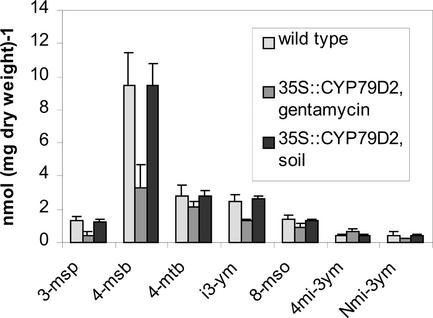

When 35S::CYP79D2 plants were germinated on gentamycin, the content of endogenous glucosinolates was significantly lower than in wild type (Figs. 1A and 4). The lower concentration of endogenous glucosinolates is not unexpected as the biosynthesis of many glucosinolates are under strict developmental control (Petersen et al., 2002). However, no differences in growth or in the profile of endogenous glucosinolates were seen between wild-type and 35S::CYP79D2 plants when germinated on soil. This indicates that the postaldoxime enzymes in the glucosinolate pathway are not rate limiting, and that the capacity for production and storage of glucosinolates can exceed the level found in uninduced wild-type plants.

Figure 4.

Glucosinolate content in wild-type and 35S::CYP79D2 grown on selective medium or soil. Plants were germinated on soil or on Murashige and Skoog plates containing no antibiotic or gentamycin for wild-type and 35S::CYP79D2 plants, respectively. Two weeks after germination, the plants on Murashige and Skoog plates were transferred to soil. After 6 weeks, glucosinolates were extracted from rosette leaves and were analyzed by HPLC. In 35S::CYP79D2 plants grown in the presence of gentamycin, the concentration of endogenous glucosinolates was significantly lower compared with wild type. However, in soil-grown 35S::CYP79D2 plants, the content of endogenous glucosinolates was virtually identical to that of wild type. No significant difference was seen between wild type germinated on nonselective medium or soil.

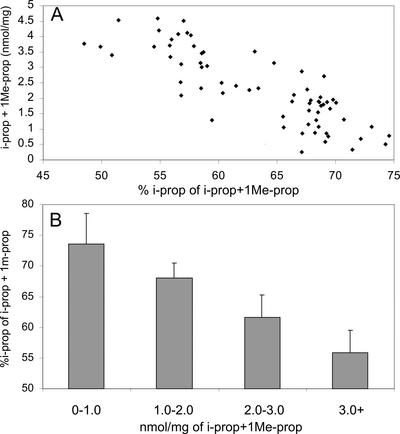

When data was combined for all examined plants, i-prop accounted for 65% ± 8% (w/v) of the two novel glucosinolates produced. This is in accordance with the in vitro activity of the recombinant CYP79D2, of which the conversion rate of Ile is approximately 60% of that observed for Val (Andersen et al., 2000). The variation in the ratio of i-prop to 1Me-prop was less than 1% when multiple plants from any single line were examined (data not shown). The level of i-prop and 1Me-prop in old leaves were generally higher than in mature leaves (data not shown). This could be due to the longer time the plants have had to accumulate the novel glucosinolates. In old leaves, the novel glucosinolates accounted for 34% to 48% of the total glucosinolate content, and the percentage of i-prop decreased to approximately 55% ± 5% of the sum of i-prop and 1Me-prop. When the ratio of i-prop to 1Me-prop was compared with the total amount of i-prop and 1Me-prop, a correlation was found in which a higher total concentration of i-prop and 1Me-prop correlated with a lower ratio of i-prop to 1Me-prop (Fig. 5A). In general, the higher the concentration of i-prop and 1Me-prop, the higher the percentage of the novel glucosinolates were accounted for by 1Me-prop. This explains the very low variation between plants from the same line as they contain similar concentrations of i-prop and 1Me-prop. Furthermore, it explains the decreasing ratio of i-prop to 1Me-prop in old leaves, as the total concentration of the novel glucosinolates in this tissue in general was higher. The correlation was clearly visualized when data from lines containing 0–1.0, 1.0–2.0, 2.0–3.0, and more than 3.0 nmol mg−1 of the novel glucosinolates were combined (Fig. 5B). These data indicated that i-prop accumulation at high concentrations was restricted due to slower metabolism of Val or its aldoxime or due to specific degradation of i-prop.

Figure 5.

The ratio of i-prop to 1Me-prop in relation to total content of i-prop and 1Me-prop in leaves from 35S::CYP79D2 lines. A, Scatterplot of ratio of i-prop to 1Me-prop versus total amount of i-prop and 1Me-prop. The plot comprises data from the 31 independent lines in the T1 generation, mature, and old leaves of homozygous lines 5, 6, 8, 10, and 28. One data point from the T1 generation highest expressing line (28) has been omitted for clarity. B, Grouping of 35S::CYP79D2 lines containing, respectively, less than 1.0, 1.0 to 2.0, 2.0 to 3.0, or more than 3.0 nm mg−1 i-prop and 1Me-prop. Columns 0 through 1.0 through 3.0+ represent 15, 20, 12, and 23 independent measurements, respectively.

The effect of growth conditions on the accumulation of i-prop and 1Me-prop in 35S::CYP79D2 plants was investigated by growing the plants in 8, 12, and 16 h of light followed by analysis of the glucosinolate content in mature rosette leaves 4 weeks after germination. Only small differences were seen in mature leaves from 35S::CYP79D2 plants grown at 8-, 12-, or 16-h light periods (data not shown). Furthermore, no physiological phenotype was observed under any of these conditions, and the levels of endogenous glucosinolates were unchanged compared with wild type.

DISCUSSION

Arabidopsis transformed with the exogenous cassava CYP79D2 under control of the 35S promotor was shown to produce two novel glucosinolates, i-prop and 1Me-prop, which are not natural constituents in this ecotype. This shows that the Val- and Ile-derived aldoximes produced by CYP79D2 are efficiently converted by the postaldoxime enzymes to the corresponding glucosinolates. Metabolic engineering of Arabidopsis with 35S-driven CYP79A1, CYP79A2, or CYP79B2 have previously been shown to produce approximately 52, 18, and 24 nmol mg−1 dry weight of Tyr-, Phe-, and Trp-derived glucosinolates, respectively (Bak et al., 1999; Mikkelsen et al., 2000; Wittstock and Halkier, 2000; Petersen et al., 2001). This is significantly more than the 8.2 nmol mg−1 found in mature leaves of the 35S::CYP79D2 plants. The relatively low accumulation of i-prop and 1Me-prop is unlikely to be due to position effect of the transgene as 31 different lines were examined. A possible explanation could be that CYP79D2 is a less efficient or less stable enzyme. The Km values of CYP79A1, CYP79A2, and CYP79B2 are 220 μm (Halkier et al., 1995), 6.7 μm (Wittstock and Halkier, 2000), and 21 μm (Mikkelsen et al., 2000), respectively, whereas the Km values for CYP79D1 is 2.2 and 1.3 mm for Val and Ile, respectively (Andersen et al., 2000). The Km values for CYP79D2 have not been determined, but are likely to be in the same range as those of CYP79D1 as the two recombinant enzymes show similar conversion rates of Val and Ile (Andersen et al., 2000). High Km values of CYP79D2 may have limited aldoxime production and thereby accumulation of i-prop and 1Me-prop. In an alternate manner, the availability of the substrates for CYP79D2 may have been reduced if the Val and Ile pools were not efficiently feedback up-regulated in response to the increased draw from the pool. Acetohydroxy acid synthase is the first common enzyme in biosynthesis of branched chain amino acids. Leu, Val, and Ile are each able to inhibit acetohydroxy acid synthase, although the most efficient inhibition is caused by the combination of excess Leu and Val (Lee and Duggleby, 2001). Therefore, the application of excess Leu and Val may create a condition of Ile starvation, which results in growth inhibition. In accordance with this, depletion or reduction of the Val and Ile pools may result in starvation if Leu inhibits Val and Ile biosynthesis. However, in this case, one would expect to see inhibition of growth in these plants, which was not observed. The expected Km values of CYP79D2 suggest that the size of amino acid pools may never be reduced further than to a level where CYP79D2 is unable to efficiently bind and metabolize the substrates. It has been suggested that the relatively high Km values of CYP79D1 function to impede the chance of amino acid starvation (Andersen et al., 2000). However, depletion of the amino acid pools could explain the decreasing ratio of i-prop to 1Me-prop with increasing overall i-prop and 1Me-prop concentrations, if the Val pool was depleted first.

An interesting feature of the 35S::CYP79D2 plants was the almost identical ratio of i-prop to 1Me-prop in several plants representing the same line, whereas a larger variation was observed between different transgenic lines. In general, the ratio of i-prop to 1Me-prop was similar for lines containing comparable quantities of the novel glucosinolates, whereas the i-prop concentration decreased relative to the 1Me-prop concentration at increasing levels of the novel glucosinolates. The reason for this is not understood. It may be that the difference in the i-prop to 1Me-prop ratio is due to differences in substrate availability or due to increased turnover of specifically i-prop at increasing i-prop concentration.

Different approaches for metabolic engineering of glucosinolate profiles are required depending on which glucosinolates are the target. The condensing enzymes in the chain elongation pathway are likely to be rate limiting for engineering of glucosinolates derived from chain-elongated protein amino acids. At present, the substrate specificity and number of condensing enzymes have not been determined (Campos et al., 2000; Kroymann et al., 2001). For glucosinolates derived from protein amino acids, the CYP79s are the first committed step and the rate-limiting step. This makes the CYP79s particularly powerful tools for (over-) expression and knockout strategies (for review, see Mikkelsen et al., 2002). Secondarily modified glucosinolate side chains are often the determining factor for the biological activity of the glucosinolate degradation products. However, the outcome of engineering of modifying enzymes is not easily predicted, as a knockout mutant will result in accumulation of the preceding intermediate, and overexpression might not have any effect if it is not a rate-limiting step. In the present study, we have generated transgenic Arabidopsis plants that produce two novel glucosinolates derived from Val and Ile while maintaining wild-type morphological and glucosinolate phenotype. Furthermore, although isothiocyanates with small side chains are generally less toxic than those with larger side chains (Borek et al., 1998), the Val- and Ile-derived isothiocyanates have potentially beneficial effects as insect repellents and biofumigants due to their high volatility. In general, it is difficult to predict the success of metabolic engineering as Km values, turnover, pool rebuilding, enzyme stability, and other presently unknown factors influence the outcome. However, with the recent advances in our understanding of the glucosinolate biosynthesis (Wittstock and Halkier, 2002), it has become a realistic goal to produce custom-designed crop plants enriched in desirable glucosinolates and without unwanted glucosinolates. This will ultimately improve nutritional value, including cancer-preventing properties, as well as increase resistance to herbivores and pathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of Transgenic Arabidopsis Expressing CYP79D2

The full-length CYP79D2 cDNA was amplified by PCR using primers CYP79D2forward (5′-ATCGTCGGATCCATGGCCATGAACGTCTCC-3′) and CYP79D2reverse (5′-CTGCTATCTAGATCAAGGTGAAGTGGGG-3′) to incorporate BamHI/XbaI restriction sites. The PCR product was cloned into BamHI/XbaI-digested pRT101 (Töpfer et al., 1987) and sequenced. The expression cassette, including the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter, was excised from pRT101 by HindIII digestion and was transferred to pPZP221 (Hajdukiewicz et al., 1994). Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58C1/pGV3850 (Zambryski et al., 1983) was transformed with the pPZP221 cauliflower mosaic virus 35S::CYP79D2 construct by electroporation and was used to transform Arabidopsis ecotype Colombia by A. tumefaciens-mediated DNA transfer. This was accomplished using the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998) with 0.005% (v/v) Silwet L-77 and 5% (w/v) Suc in 10 mm MgCl2. Seeds were germinated on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium supplemented with 100 μg mL−1 gentamycin, 3% (w/v) Suc, and 0.9% (w/v) agar. Transformants were selected after 2 to 4 weeks and were transferred to soil.

Sequencing and Sequence Analysis

Sequence analysis was performed using Thermo Sequence Fluorescent-labeled Primer cycle sequencing kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) and was analyzed on an ALF-express automated sequenator (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Sequence computer analysis was accomplished using programs of the Wisconsin Sequence Analysis Package.

Growth of Plants

Arabidopsis ecotype Colombia was used for all experiments. Plants were grown in a controlled environment Arabidopsis chamber (AR-60 I; Percival, Boone, IA) at a photosynthetic flux of 100 to 120 nmol photons m−2 s−1 at 20°C and 70% relative humidity. The photoperiod was 8, 12, or 16 h. Leaves from Capparis flexuosa and Putranjiva roxburghii were kindly supplied by the Copenhagen Botanical Garden.

HPLC Analysis of Glucosinolates

Glucosinolates were extracted from approximately 20 mg of slightly homogenized freeze-dried rosette leaves by boiling for 4 min in 4 mL of 70% (v/v) methanol. The supernatant was collected and the plant material was washed with 2 mL of 70% (v/v) methanol. The extracts were combined and applied to 200 μL of diethylaminoethyl Sephadex CL-6B (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) columns (Polyprep; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) equilibrated with 1 mL of 20 mm KOAc, pH 5.0, and washed with 1 mL of water. The columns were washed with 2 mL of 70% (v/v) methanol, 2 mL of water, and 2 mL of 20 mm KOAc, pH 5. After the addition of 100 μL of 2.5 mg mL−1 Helix pomatia sulfatase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis), the columns were sealed and left overnight. The resulting desulphoglucosinolates were eluted with 2 × 1 mL water. The eluate was lyophilized until dryness and was resuspended in 200 μL of water. Aliquots of 100 μL were applied to a HPLC system (Spectachrom; Shimadzu, Columbia, MD) equipped with a supelcosil LC-ABZ 59142 RP-amid C-16 (25 cm × 4.6 mm, 5 mm; Supelco, Bellefonte, PA; Holm and Halby, Denmark) and an SPD-M10AVP photodiode array detector (Shimadzu). The flow rate was 1 mL min−1. Desulphoglucosinolates were eluted with water for 2 min followed by a linear gradient from 0% to 60% (v/v) methanol in water (48 min), a linear gradient from 60% to 100% (v/v) methanol in water (3 min), and with 100% (v/v) methanol (14 min). Detection was performed at 229 and 260 nm using a photodiode array. Desulphoglucosinolates were quantified based on response factors (Buchner, 1987; Haughn et al., 1991) and internal benzylglucosinolate- (Merck, West Point, PA) or p-hydroxybenzyl glucosinolate (Bioraf, Åkirkeby, Denmark) standards as previously described (Petersen et al., 2001, 2002). The standard was added at the beginning of the extraction procedure. Except for analysis of the T1 generation, all experiments were made in triplicates. However, results from the highest expressing T1 lines were repeated using homozygous T3 lines.

LC-MS Analysis of Glucosinolates

Desulphoglucosinolates obtained as described above were subjected to LC-MS analysis. LC-MS was performed using an HP1100 LC (GMI, Albertville, MN) coupled to an iontrap mass spectrometer (Esquire-LC; Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany). The reversed-phase LC conditions were as follows: A C18 column (Chrompack Inertsil 3 ODS-3 S15 × 3 COL CP 29126, Analytical Instruments A/s, Vaerløse, Denmark) was used. The mobile phases were A: water doped with sodium acetate (50 μm), and B: methanol. The flow rate was 0.25 mL min−1 and the gradient program was 0 to 2 min: isocratic 100% A; 2 to 40 min: linear gradient 0% to 60% B; 40 to 45 min: linear gradient 60% to 100% B; and 45 to 50 min: isocratic 100% B. The mass spectrometer was run in positive-ion mode. A 15-μL aliquot of each glucosinolate preparation was injected. Total ion currents and UV traces were used to locate peaks, and the [M + Na]+ adduct ions in conjunction with diode array UV spectra were used for identification.

Footnotes

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.013425.

LITERATURE CITED

- Andersen MD, Busk PK, Svendsen I, Møller BL. Cytochromes P-450 from cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) catalyzing the first steps in the biosynthesis of the cyanogenic glucosides linamarin and lotaustralin: cloning, functional expression in Pichia pastoris, and substrate specificity of the isolated recombinant enzymes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1966–1975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak S, Olsen CE, Petersen BL, Møller BL, Halkier BA. Metabolic engineering of p-hydroxybenzylglucosinolate in Arabidopsis by expression of the cyanogenic CYP79A1 from Sorghum bicolor. Plant J. 1999;20:663–671. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borek V, Elberson LR, McCaffrey JP, Morra MJ. Toxicity of isothiocyanates produced by glucosinolates in Brassicacea species to Black Vine Weevil eggs. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:5318–5323. [Google Scholar]

- Buchner R. Glucosinolates in rapeseeds: analytical aspects. In: Wathelet JP, editor. World Crops: Production, Utilization, Description. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; 1987. pp. 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Campos H, Magrath R, McCallum D, Kroymann J, Schnabelrauch D, Mitchell-Olds T, Mithen R. α-Keto acid elongation and glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Theor Appl Genet. 2000;101:429–437. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Glawischnig E, Jørgensen K, Naur P, Jørgensen B, Olsen CE, Hansen CH, Rasmussen H, Pickett J, Halkier BA (2003) CYP79F1 and CYP79F2 have distinct functions in the biosynthesis of aliphatic glucosinolates in Arabidopsis. Plant J (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey JW, Zalcmann AT, Talalay P. The chemical diversity and distribution of glucosinolates and isothiocyanates among plants. Phytochemistry. 2001;56:5–51. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grootwassink JWD, Balsevich JJ, Kolenovsky AD. Formation of sulfatoglucosides from exogenous aldoximes in higher plant cell cultures and organs. Plant Sci. 1990;66:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hajdukiewicz P, Svab Z, Maliga P. The small versatile pPZP family of Agrobacterium binary vectors for plant transformation. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;25:989–994. doi: 10.1007/BF00014672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkier BA. Glucosinolates. In: Ikan R, editor. , Naturally Occurring Glycosides. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1999. pp. 193–223. [Google Scholar]

- Halkier BA, Hansen CH, Naur P, Mikkelsen MD, Wittstock U. The role of cytochromes P450 in biosynthesis and evolution of glucosinolates. In: Romeo JT, editor. Recent Advances in Phytochemistry. Vol. 36. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 2002. pp. 223–248. [Google Scholar]

- Halkier BA, Nielsen HL, Koch BM, Møller BL. Purification and characterization of recombinant cytochrome P450TYR expressed at high levels in Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;322:369–377. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen CH, Wittstock U, Olsen CE, Hick AJ, Pickett JA, Halkier BA. Cytochrome P450 CYP79F1 from Arabidopsis catalyzes the conversion of dihomomethionine and trihomomethionine to the corresponding aldoximes in the biosynthesis of aliphatic glucosinolates. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11078–11085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haughn GW, Davin L, Giblin M, Underhill EW. Biochemical genetics of plant secondary metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana: the glucosinolates. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:217–226. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.1.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull AK, Rekha V, Celenza JL. Arabidopsis cytochrome P450s that catalyze the first step of tryptophan-dependent indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2379–2384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040569997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliebenstein DJ, Lambrix VM, Reichelt M, Gershenzon J, Mitchell-Olds T. Gene duplication in the diversification of secondary metabolism: tandem 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases control glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2001;13:681–693. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.3.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroymann J, Textor S, Tokuhisa JG, Falk KL, Bartram S, Gershenzon J, Mitchell-Olds T. A gene controlling variation in Arabidopsis glucosinolate composition is part of the methionine chain elongation pathway. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:1077–1088. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y-T, Duggleby RG. Identification of the regulatory subunit of Arabidopsis thaliana acetohydroxy acid synthase and reconstitution with its catalytic subunit. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6836–6844. doi: 10.1021/bi002775q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen MD, Hansen CH, Wittstock U, Halkier BA. Cytochrome P450 CYP79B2 from Arabidopsis catalyzes the conversion of tryptophan to indole-3-acetaldoxime, a precursor of indole glucosinolates and indole-3-acetic Acid. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33712–33717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001667200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen MD, Petersen BL, Olsen CE, Halkier BA. Biosynthesis and metabolic engineering of glucosinolates. Amino Acids. 2002;22:279–295. doi: 10.1007/s007260200014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen JS, Møller BL. Cloning and expression of cytochrome P450 enzymes catalyzing the conversion of tyrosine to p-hydroxyphenylacetaldoxime in the biosynthesis of cyanogenic glucosides in Triglochin maritima. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:1311–1321. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.4.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen BL, Andreasson E, Bak S, Agerbirk N, Halkier BA. Characterization of transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana with metabolically engineered high levels of p-hydroxybenzylglucosinolate. Planta. 2001;212:612–618. doi: 10.1007/s004250000429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen BL, Chen S, Hansen CH, Olsen CE, Halkier BA. Composition and content of glucosinolates in developing Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2002;214:562–571. doi: 10.1007/s004250100659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rask L, Andreasson E, Ekbom B, Eriksson S, Pontoppidan B, Meijer J. Myrosinase: gene family evolution and herbivore defense in Brassicacea. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;42:93–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raybould AF, Moyes CL. The ecological genetics of aliphatic glucosinolates. Heredity. 2001;87:383–391. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2001.00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talalay P, Fahey JW. Phytochemicals from cruciferous plants protect against cancer by modulating carcinogen metabolism. J Nutr. 2001;131:3027S–3033S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.3027S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Töpfer R, Matzeit V, Gronenborn B, Schell J, Steinbiss H. A set of plant expression vectors for transcriptional and translational fusions. Nucleic Acid Res. 1987;15:5890. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.14.5890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittstock U, Halkier BA. Cytochrome P450 CYP79A2 from Arabidopsis thaliana L. catalyzes the conversion of l-phenylalanine to phenylacetaldoxime in the biosynthesis of benzylglucosinolate. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14659–14666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittstock U, Halkier BA. Glucosinolate research in the Arabidopsis era. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:263–270. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambryski P, Genetello C, Leemans J, Van Montagu M, Schell J. Ti-plasmid vector for the introduction of DNA into plant cells without alteration of their normal regeneration capacity. EMBO J. 1983;2:2143–2152. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01715.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]