Abstract

Modulation of intracellular calcium levels plays a key role in the transduction of many biological signals. Here, we characterize early calcium responses of wild-type and mutant Medicago truncatula plants to nodulation factors produced by the bacterial symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti using a dual-dye ratiometric imaging technique. When presented with 1 nm Nod factor, root hair cells exhibited only the previously described calcium spiking response initiating 10 min after application. Nod factor (10 nm) elicited an immediate increase in calcium levels that was temporally earlier and spatially distinct from calcium spikes occurring later in the same cell. Nod factor analogs that were structurally related, applied at 10 nm, failed to initiate this calcium flux response. Cells induced to spike with low Nod factor concentrations show a calcium flux response when Nod factor is raised from 1 to 10 nm. Plant mutants previously shown to be deficient for the calcium spiking response (dmi1 and dmi2) exhibited an immediate, truncated calcium flux with 10 nm Nod factor, demonstrating a competence to respond to Nod factor but an impaired ability to generate a full biphasic response. These results demonstrate that the legume root hair cell exhibits two independent calcium responses to Nod factor triggered at different agonist concentrations and suggests an early branch point in the Nod factor signal transduction pathway.

The Rhizobium/legume symbiosis begins with a discrete interchange of signals (for reviews, see Dénarié et al., 1996; Long, 1996). Soil-borne bacteria, induced by plant-derived flavonoids, produce a host-specific lipochitooligosaccharide signaling molecule, the Nod factor. In response to Nod factor, the plant root undergoes a series of changes, including permissive infection by the bacteria and development of a nodule where bacteria fix nitrogen into the biosphere. The earliest steps in Nod factor perception are plasma membrane depolarization, ion fluxes, and intracellular calcium ion spiking (for review, see Cárdenas et al., 2000). Characterization of plant mutants defective for nodule development is providing a link between early ionic responses and subsequent events (e.g. gene expression, cellular growth changes, and bacterial infection) required for nitrogen fixation (Catoira et al., 2000; Wais et al., 2000; Oldroyd et al., 2001; Endre et al., 2002). With this work, we have used improved imaging methods and nodulation mutants to clarify the relationship between the early calcium responses thus far reported for the Rhizobium/legume interaction.

Nod factor triggers a movement of calcium ions into the cell cytoplasm within the first minutes of application, nearly coincident with plasma membrane depolarization (Felle et al., 1998; Cárdenas et al., 1999; for review, see Cárdenas et al., 2000). Both phenomena have been characterized in plant cells responding to pathogenic elicitors, including chitins, oligosaccharides, and several peptides/peptidoglycans (for reviews, see Boller, 1995; Yang et al., 1997; Scheel, 1998). The induction of mitogen-activated protein kinase activity, peroxide production, and defense-related gene expression have been documented for these interactions, and evidence exists implicating calcium ion flux as a requirement for the downstream events (Nürnberger et al., 1994; Ligterink et al., 1997; Romeis et al., 1999; Blume et al., 2000).

Oscillations or spikes in calcium concentration in or around the nucleus begin approximately 10 min after sensing Nod factor in alfalfa (Medicago sativa), Medicago truncatula, and pea (Pisum sativa) plants (Ehrhardt et al., 1996; Wais et al., 2000; Walker et al., 2000). Calcium oscillations in animal cells have been linked to gene expression where amplitude and periodicity contribute to the specificity of the response (de Koninck et al., 1998; Dolmetsch et al., 1997, 1998; Li et al., 1998). Oscillations in plant cells have been observed in stomatal guard cells (McAinsh et al., 1995) and have been shown to regulate stomatal aperture (Allen et al., 2000). Other potential roles for calcium spiking in plant systems have yet to be established (Sanders et al., 1999). Though the calcium flux and calcium spiking response in legumes have not been shown to be required for bacterial infection or nodule biogenesis, nodulation mutants lacking the calcium spiking response (Wais et al., 2000; Walker et al., 2000) support the supposition that early ionic changes are part of the nodulation signaling pathway.

Membrane depolarization responses and calcium entry occur in alfalfa at Nod factor concentrations of 1 to 10 nm under perfusion (Felle et al., 1995, 1998). Calcium spiking appears at concentrations as low as 1 to 10 pm, a roughly 1,000-fold difference in agonist concentration for the two responses (Ehrhardt et al., 1996; Oldroyd et al., 2001). Although the range of physiologically relevant Nod factor concentrations has not been similarly defined for other downstream events, the apparent difference in sensitivity suggests potentially different mechanisms for reception. The relationship between the two phenomena is unknown owing primarily to the different techniques used for recording the responses. The early calcium flux into alfalfa root hairs was shown using calcium-selective microelectrodes inside and outside of the cell (Felle and Hepler, 1997; Felle et al., 1999b). However, not observed with microelectrode recording techniques are the spikes in cytoplasmic calcium, originally described in alfalfa using calcium indicator dyes. Events preceding calcium spiking could not be recorded using the ratiometric dye, FURA-2, due to toxic effects of the dye in alfalfa root hairs (Ehrhardt et al., 1996). Single wavelength dyes have been reliably used for subsequent investigations of calcium spiking (Wais et al., 2000; Walker et al., 2000; Oldroyd et al., 2001), but have not permitted the accurate evaluation of events preceding calcium spiking.

In this paper, we have used a dual-dye imaging technique to observe calcium spiking and singular rises in cytoplasmic calcium concentration resulting from exposure to Nod factor. Using the model legume M. truncatula (Cook, 1999), we show that root hair cells have two distinct and separable responses to the same Nod factor signaling molecule when provided that molecule at different concentrations. Plants previously shown to be mutant for the calcium spiking response show a truncated calcium flux response when exposed to Nod factor. We discuss the possible implications for the incremental response to Nod factor as a proximity sensor for symbiotic bacteria.

RESULTS

Cytoplasmic Calcium Changes in Response to Nod Factor

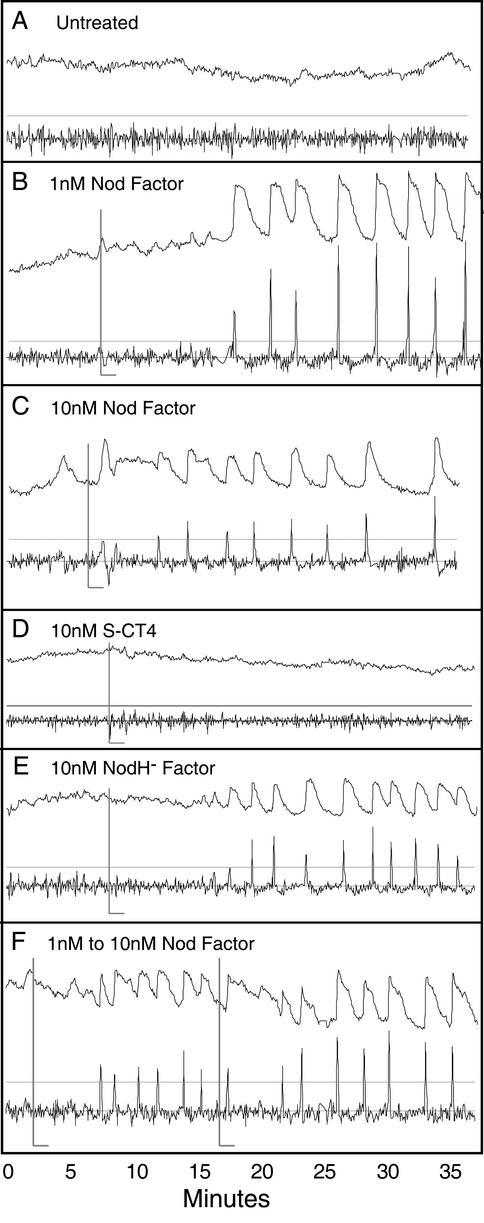

Root hair cells of M. truncatula were assayed for changes in cytoplasmic calcium concentration in response to Sinorhizobium meliloti Nod factor (NodRmIV16:2,Ac,S). A ratio-imaging technique using Dextran-coupled fluorescent dyes was developed (see “Materials and Methods”) to unambiguously identify singular and repetitive changes in cytoplasmic calcium ion concentration, independent from local changes in cytoplasmic volume (Fig. 1). Multiple root hair cells per plant were iontophoretically microinjected with the combined dyes and were simultaneously ratio imaged for >45 min. Ratio values, representing the entire root hair cell, were plotted over time from untreated, wild-type plants (Fig. 1A). Wild-type plants showed increases in fluorescence ratios, including symmetric peaks (see Fig. 1C at 4 min) and occasional low-amplitude oscillatory patterns, not observed for the combined dyes imaged between coverslips or in cells no longer exhibiting cytoplasmic streaming (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Relative changes in cytoplasmic calcium concentration associated with Nod factor treatment of M. truncatula root hair cells. The ratio of calcium-sensitive to calcium-insensitive dye (arbitrary units) for an entire cell plotted at 4-s intervals for >35 min. Data are presented as unscaled ratios (top trace) and a derivative trace (scaled 2.5×) with the gray line representing 3.5 sds of the mean for the first 7 min of the derivative trace (see “Materials and Methods”). Untreated cell (A) showing occasional fluctuations of low amplitude and duration. Also note the symmetric rise at 4 min in C before Nod factor addition. Treatment with Nod factor at <1 nm final bath concentration (B, gray L bar denotes time of application) produces no significant change in calcium concentration before the onset of calcium spiking. Nod factor treatment at 10 nm final bath concentration (C) results in an immediate, biphasic cytoplasmic calcium flux followed by calcium spiking. Structurally related sulfated chitotetraose (S-CT4; D) and NodH− (E) factor, both at 10 nm, show no evidence of a rapidly induced change in calcium concentration. Nod factor addition (10 nm) to plants previously induced to spike with 1 nm Nod factor (F) results in a calcium flux, indicating that the spiking cells are not desensitized to the Nod factor-induced calcium flux.

Iontophoresis resulted in differing ratios of injected dye for each cell, preventing the accurate calibration of fluorescence units to calcium ion concentration. Therefore, the previously characterized calcium spikes (Ehrhardt et al., 1996; Wais et al., 2000) were used as an internal standard for assessing the magnitude of other calcium changes within the cell (Fig. 1B). The repetitive changes in fluorescence ratio appearing in response to Nod factor (calcium spikes) generally exhibit an increase over a 4-s time-lapsed interval greater than 3 sds above the mean fluorescence ratio change for cells prior to Nod factor treatment. Therefore, a change in fluorescence ratio 3.5 times greater than the mean value for the cell prior to addition of agonist was used to find peaks and to distinguish rapid changes in calcium concentration from background noise and drift in the traces (see “Materials and Methods”).

Nod factor applied at a final bath concentration of ≤1 nm produced no increase in the cytoplasmic calcium levels before calcium spiking in the majority of cases (n = 24/37 cells from 16 plants; Figs. 1B and 2). Cytoplasmic calcium spiking initiated 7 to 25 min after the Nod factor addition and persisted throughout the experiment (>35 min). In at least four of 13 cases where an increase in calcium appeared before spiking, Nod factor was introduced into the bath from stocks directly on to cells rather than from the far edge of the assay bath before mixing. In these instances, an increase in calcium was observed within 2 to 3 min of Nod factor addition and likely resulted from momentary exposure to relatively high (100 nm stock) local concentrations of Nod factor.

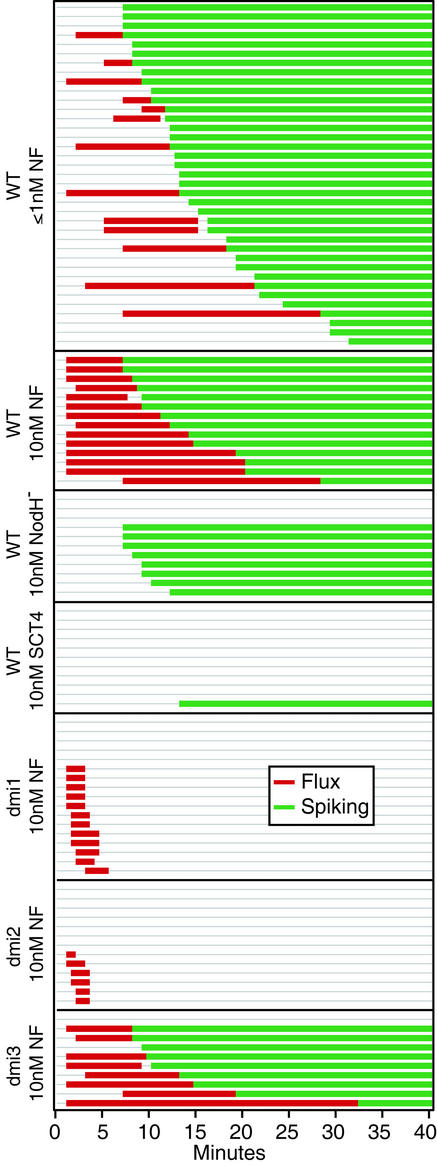

Figure 2.

Compilation of Nod factor response data. Indications of a calcium flux response (red bars) or calcium spiking response (green bars) are plotted over time for all cells. Cells were treated at time 0 and were imaged for a minimum of 40 min. Times were rounded to the nearest 30-s interval and data were sorted for each treatment by lag time to spiking.

The application of Nod factor to 10 nm final bath concentration resulted in a rapid and immediate elevation in cytoplasmic calcium concentration (n = 14/14 cells from six plants; Figs. 1C and 2). The increase in fluorescence appeared biphasic in character (n = 10/14 cells) initiating 1 to 3 min after application of Nod factor to the medium. After an initial phase of calcium elevation (1–3 min), levels remained elevated until calcium spiking began 7 to 25 min later. The lag period between the initial flux and the onset of spiking, although variable in duration, was a consistent feature of all calcium traces where 10 nm Nod factor was used. In no case did calcium spiking begin before the previously characterized lag period (Ehrhardt et al., 1996; Wais et al., 2000; >6 min).

Two molecules structurally related to Nod factor were used to assess the specificity of the calcium flux response in this assay. S-CT4 at 10 nm produced no calcium flux response (n = 11/11 cells from three plants) and only induced calcium spiking in one of 11 cells (Figs. 1D and 2). Nod factor lacking the reducing end sulfate group, purified from bacteria lacking the NodH gene (NodH− factor), caused calcium spiking at a 10 nm concentration (Figs. 1E and 2), but failed to reproducibly elicit a calcium flux response (n = 8/11 cells from four plants).

Calcium Flux in Spiking Cells

To determine if the calcium spiking activity in root hair cells presented with low concentrations of Nod factor desensitizes the plant to sustained calcium increases observed at higher Nod factor concentrations, cells were treated first with 1 nm Nod factor, until spiking commenced, and then the bath concentration was raised to 10 nm (Fig. 1F). A subset of cells (n = 4/12 cells from six plants) showed a sustained increase (>5 min) in cytoplasmic free calcium levels immediately after the second addition of Nod factor, indicating that the flux response can be triggered in spiking cells. The timing of the onset relative to the second Nod factor addition was used to discriminate the flux response from occasional sustained increases in calcium observed in spiking cells. Due to the presence of existing spikes, it was not possible to determine unambiguously whether or not the sustained flux was mono- or biphasic in nature.

Spatial Distribution of Calcium Changes

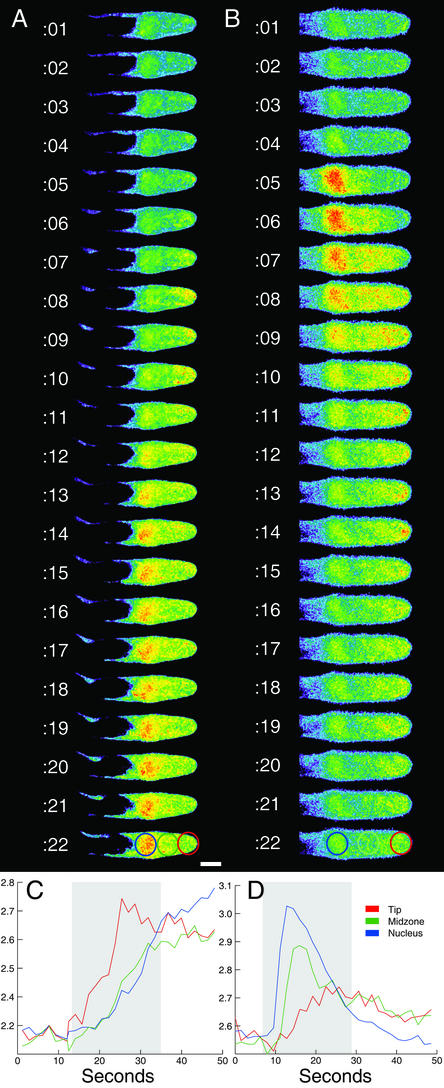

Calcium oscillations induced by Nod factor were previously shown to initiate in the nuclear region of the root hair cell (Ehrhardt et al., 1996). To determine if the calcium flux initiated by 10 nm Nod factor showed the same characteristics, ratio images were collected at 1-s intervals at high spatial resolution. Fluorescence ratios were plotted from three regions of the cell to estimate the timing of relative changes in free calcium from tip to nucleus (Fig. 3). The addition of Nod factor to 10 nm in the bathing medium resulted in a wave of calcium changes beginning at the cell perimeter and rapidly moving inward to the nucleus (n = 5/5 cells from five plants; Fig. 3, A and C). This phenomenon is illustrated most strikingly in cells where the nucleus is positioned 20 or more micrometers from the cell tip (Fig. 3A). Tip-high calcium gradients were found in several growing root hairs before Nod factor addition (S.L. Shaw and S.R. Long, unpublished data).

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of calcium changes resulting from Nod factor treatment. The calcium flux (A) and later calcium spiking (B) triggered by 10 nm Nod factor were ratio-imaged at 1-s intervals in the same cell. The mean ratio for three regions of the cell corresponding to the tip, the mid-zone region between tip, and nucleus, and the nucleus are plotted over time (C and D). The calcium flux (A and C) begins at the cell periphery and moves inward toward the nucleus. Repetitive calcium spikes originate in the nuclear area of the cell and propagate as a wave tipward (B and D). Note the highlighted regions in C and D correspond to the 22 images shown in A and B. Color scale for images (low to high) is blue, green, yellow, and red. Bar = 10 μm.

Calcium spikes originate in the nuclear region of the cell and propagate distally to the cell tip (n = 15/15 spikes from two cells on two plants; Fig. 3, B and D). The magnitude of calcium increase appears to taper off at the tip, in agreement with previously published observations. Thus, the spatial distribution and kinetics of cytoplasmic calcium changes appear to be markedly different for the initial calcium flux and for later calcium spiking. Control ratios using two sequential images of the same dye (mean ratio = 1.01, sd = 0.01) over 2 min at 1-s intervals (data not shown) indicated no contribution of cytoplasmic movement to the measurement of the calcium changes.

Mutants Respond to High Nod Factor Concentrations

Plant nodulation mutants that do not show calcium spiking in response to Nod factor have been characterized in M. truncatula (Catoira et al., 2000; Wais et al., 2000). The dmi1, dmi2, and dmi3 mutants are not competent for rhizobial infection and exhibit only a slight morphological change in the presence of Nod factor (Catoira et al., 2000). The dmi1 and dmi2 mutants lack the calcium spiking response to Nod factor, whereas the dmi3 mutant exhibits calcium spiking. Mutants were tested for responses to 10 nm Nod factor to see if the calcium flux response is separable from the calcium spiking response.

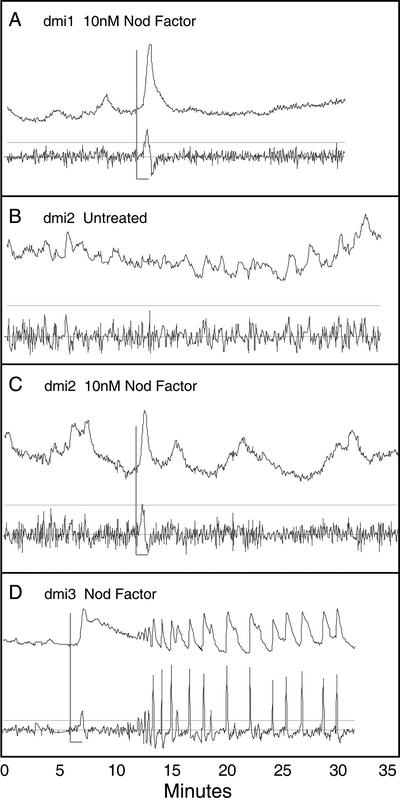

A fast neutron-generated allele of dmi1 (dmi1-4; G. Oldroyd and S.R. Long, unpublished data) showed no response to 1 nm Nod factor (data not shown) and a rapid increase in cytoplasmic calcium concentration in response to 10 nm Nod factor (n = 11/16 cells from eight plants; Figs. 2, 4A). Onset of the calcium flux occurred within the first 1 to 2 min of Nod factor application, indicative of the wild-type calcium flux response. The response to 10 nm Nod factor differed significantly from wild-type plants in that it was monophasic (compare Fig. 4A with Fig. 1C), having a rapid decline back to baseline (1–2 min) and, as previously discovered, no calcium spiking. Calcium ion concentration was observed to increase throughout the cytoplasmic area of the cell, including the nucleus.

Figure 4.

Nodulation mutants show a truncated calcium flux in the absence of calcium spiking. Three M. truncatula mutants, previously characterized for the calcium spiking response, were assayed for calcium flux response with 10 nm Nod factor. The dmi1 mutant (A, gray L bar denotes time of application) exhibits a single, monophasic calcium flux in response to Nod factor (compare with Figs. 1C and 4D). The untreated dmi2 mutant (B and C) shows episodic changes and oscillations in calcium concentration (C). The application of Nod factor (10 nm) induces a monophasic calcium flux that can be distinguished in some dmi2 plants showing less dramatic changes in background calcium levels (C). The dmi3 mutant (D), previously shown to be wild type for the calcium spiking response, exhibits a wild-type biphasic calcium flux response when exposed to 10 nm Nod factor.

The dmi2 mutant (dmi2-1 and dmi2-3 alleles) showed occasional low-amplitude calcium increases before any addition of Nod factor (Fig. 4B). This tendency to show spikes and exaggerated oscillatory patterns precluded a definitive analysis of all dmi2 cells treated with Nod factor. The addition of Nod factor to 10 nm did result in several cells showing an immediate calcium flux response resembling the monophasic spike observed in the dmi1 mutant plants (n = 7/13 cells from five plants; Figs. 2, 4C).

The dmi3 mutant, which shows root hair cytological changes that are indistinguishable from dmi1 and dmi2 but does exhibit calcium spiking in the presence of Nod factor, was wild type for the biphasic calcium flux response (Figs. 2, 4D). Upon addition of 10 nm Nod factor, an immediate and sustained rise in cytoplasmic calcium concentration was recorded, followed by calcium spiking in the nuclear region of the cell (n = 9/10 cells from three plants).

DISCUSSION

The initiation of the Rhizobium/legume symbiosis relies principally on a single class of molecules, the lipochitooligosaccharide Nod factors. The host plant uses Nod factor perception to correctly identify symbiotic bacteria for permissive infection while rejecting pathogenic microbes that may produce similar oligosaccharides. At the same time, the plant must take advantage of the rare opportunity of having a bacterium in the appropriate physical location on the root hair for initiating a successful infection. Hence, the Nod factor signal transduction mechanism requires strict structural specificity combined with a high fidelity of signal transmission. Here, we describe direct, continuous observations of single cells, showing that Nod factor encodes two separable ionic responses in the plant dependent on Nod factor concentration. These observations provide support for a bifurcation of the Nod factor signal transduction pathway and further suggest that different levels of Nod factor could lead to different cellular responses.

Nod Factor Signals for Two Independent Ionic Responses

Two distinct responses are evoked in the same plant cell by different concentrations of bacterially derived Nod factor. Using ratiometric calcium imaging, no initial response was observed in the majority of cases with low concentrations of Nod factor (<1 nm) before the onset of calcium spiking. In contrast, cells treated with higher concentrations of Nod factor (10 nm) exhibit an immediate increase in free calcium levels even if the cells were previously spiking. Comparison of the spatial distribution of the free calcium changes during these two responses strongly suggests that the calcium sources for calcium flux and calcium spiking are physically distinct. Plants mutant for the calcium spiking response still show an immediate flux in response to 10 nm Nod factor and no response at lower concentrations. These observations demonstrate that the calcium flux and calcium spiking responses occur in the same legume hair cell and that these responses are independent of one another, i.e. calcium spiking does not require and is not caused by a large initial calcium flux.

The dual-dye ratiometric technique permitted successful observation of both previously identified calcium phenomena in the same cell (Felle et al., 1995, 1997, 1999a, 1999b; Ehrhardt et al., 1996; Felle, 1996). Felle (1999a, 1999b) demonstrated, using calcium-selective microelectrodes, that Nod factor at >1 nm concentration triggers a calcium ion influx of 0.5 pCa specific for Nod factor when compared with chitin oligomers and other related molecules. The rapid increase in free cytosolic calcium concentration observed by ratio imaging shows similar kinetics and, based on comparisons with calcium spikes measured previously in alfalfa (rising from 50–400 nm; Ehrhardt et al., 1996), show similar changes in concentration. The biphasic nature of the flux response appears far less pronounced in the electrophysiological characterizations, possibly due to the microelectrode measuring only a single region of the cell. Comparing ratio values obtained simultaneously from different regions of the cell suggests that the biphasic components of the flux response are spatially distinct; the initial spike occurs near the tip of the cell and the subsequent elevation occurs near the nuclear region. Calcium spiking was observed at all Nod factor concentrations for wild-type plants, and the lag time between Nod factor presentation and spiking occurred even when Nod factor was added directly onto root hairs from 100 nm stocks. Hence, our observations in M. truncatula appear consistent with previous characterizations of early ionic changes induced by Nod factor in alfalfa root hair cells.

Mutants in Nod Factor Signal Transduction

The dmi1 mutant exhibits a single, brief rise and fall in calcium concentration in response to 10 nm Nod factor. In comparison with the biphasic wild-type response, we conclude that the dmi1 plants are impaired not only in the ability to generate repetitive calcium spikes, but are also mutant for the second phase of the calcium flux response (compare Fig. 4A with 1C and 4D). Analysis of the time-lapsed ratio images for the wild-type calcium flux shows that the initial increase occurs at the periphery of the cell and that the later phase of the calcium flux originates in or around the nucleus. The possibility that the same calcium source used to generate calcium spikes is also required for the generation of the second phase of the calcium flux is currently being investigated (S.L. Shaw, unpublished data).

Unlike dmi1 mutants, dmi2 mutants show significant changes in calcium concentration in the absence of Nod factor treatment. Calcium increases often appeared in series as short periods of spiking or longer oscillations, making the interpretation of Nod factor-induced phenomena difficult. Peaks appearing in untreated wild-type plants are nearly symmetric, whereas the unelicited spikes in the dmi2 plants are exaggerated in amplitude and often show the sawtooth morphology more characteristic of Nod factor-induced calcium spiking. The appearance of a singular rise and fall in calcium ion concentration immediately after Nod factor addition supports our conclusion that the dmi2 mutants are responding with a monophasic calcium flux, similar or identical to the dmi1 mutant.

Nod Factor Signaling Pathway

Mild root hair swelling and a calcium flux response in all three dmi mutants indicate that a Nod factor signal is being transduced. The appearance of a biphasic calcium flux and calcium spiking in the dmi3 mutant, which shows an identical morphological phenotype to dmi1 and dmi2 (Catoira et al., 2000), predicts that the second phase of the calcium flux response and calcium spiking per se are not sufficient for the direction of root hair branching and other related deformation activities (Heidstra et al., 1994). The cloning of the mutation responsible for the dmi2 phenotype in M. truncatula (NORK) and the genes putative role as a receptor kinase are interesting (Endre et al., 2002). We propose that the initial phase of the calcium flux response is, together or consequent with membrane depolarization, one of the earliest responses to Nod factor and is independent of DMI1 and DMI2 activity. The second phase of the calcium flux appears to be downstream of DMI1 and DMI2 and may be related in mechanism to the generation of calcium spikes.

The lag time between Nod factor perception and calcium spiking remains unexplained. Our leading hypothesis for the presence of a lag was that an early calcium flux raised the calcium levels for approximately 10 min before giving way to a spiking pattern. This is the case using 10 nm Nod factor. However, using a second, noncalcium responsive dye for ratio imaging, the absence of any dramatic changes in calcium level before the initiation of spiking at approximately 10 min can clearly and unambiguously be observed when Nod factor is provided at 1 nm or lower concentrations.

Exhibiting two concentration-dependent Nod factor responses in the same cell suggests that there is a single receptor having multiple activities or that multiple receptors control the full breadth of Nod factor activity. Previous work showing that some nodulation responses require more Nod factor structural specificity than others has been used in support of a two receptor model for Nod factor perception (Ardourel et al., 1994; Heidstra and Bisseling, 1996; Minami et al., 1996). It is interesting that chitin tetramer at micromolar concentration elicits calcium spiking responses in pea and M. truncatula (Walker et al., 2000; Oldroyd et al., 2001), but did not cause significant membrane depolarization in alfalfa at 1 μm or a change in internal calcium concentration at 0.1 μm (Felle et al., 2000, 1999b). The chitin-induced response is lost in dmi1 and dmi2 mutants (S.L. Shaw and S.R. Long, unpublished data), suggesting that a chitin receptor is triggering the Nod factor calcium spiking response or that high levels of chitin can trigger the Nod factor receptor to initiate calcium spiking. That chitin tetramers did not induce membrane depolarization or calcium changes in alfalfa suggests that there is a separate receptor for the calcium flux response or that chitin simply cannot stimulate the existing Nod factor receptor to a high enough activity to trigger the flux response. This explanation is equally applicable to the results presented for the sulfated chitin tetramer and the NodH− factor in this work.

Perspectives on a Possible Dual-Signaling Function

Dose-response experiments using purified Nod factors indicate a threshold concentration of 1 to 10 pm for calcium spiking (Ehrhardt et al., 1996; Oldroyd and Long, 2001), or roughly, a few Nod factor molecules per root hair cell (see also Goedhart et al., 2000). Though no functional relationships have been established for calcium spiking in nodulation, the induction of the response clearly shows that Nod factor is perceived by the plant at extremely low concentrations. The calcium flux response occurs under defined conditions at 1 to 10 nm Nod factor, about four orders of magnitude higher than the concentration needed for calcium spiking. Although considerably more Nod factor is required to trigger a flux response, the cell wall shows affinity for Nod factor (Etzler et al., 1999), and accumulation of Nod factors in the root hair cell wall has been demonstrated (Goedhart et al., 2000). Hence, Nod factor concentration may be able to reach 10 nm locally over time to produce a calcium flux, especially in cases where bacteria are producing Nod factor in direct contact with the root hair or when Nod factor is being perfused for extended time periods.

One proposal from these observations is that the plant could use Nod factor concentration as a means of understanding bacterial proximity. Supernodulating mutants (Penmetsa and Cook, 1997) provide dramatic evidence that the plant normally restricts nodulation so as not to tax the plant's resources beyond the requirement for fixing nitrogen. Calcium spiking and root hair deformation are evoked at very low Nod factor concentrations, where the plant does not commit resources to the development of nodules. Bacterial infection of M. truncatula seedlings is not observed within the first 6 to 8 h after bacterial inoculation, even in cases where bacteria are preinduced for Nod factor production (S.L. Shaw and D. Keating, unpublished data). Hence, low concentrations of Nod factor present in the soil could act as a priming signal, informing the plant of potential symbiotic partners.

Having the bacterial symbiont in the correct physical location on the plant cell to induce root hair curling and infection is likely a rare event, even when the plant is aware of the bacterial symbiont. One potential mechanism for insuring that the plant cell recognizes the bound bacterium is the generation of a second response, a calcium flux, that is dependent on the local accumulation of Nod factor to concentrations greatly exceeding the concentration in the nearby rhizosphere. By having two threshold responses to Nod factor concentration, the host legume could remain extremely sensitive to the presence of the correct symbiotic partner while providing a secure means for recognizing the time and place to permit infection and initiate nodule construction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth

Seed from Medicago truncatula (Jemalong) were treated with 70% (v/v) ethanol/water for 40 min, rinsed twice in sterile water, and sterilized with 100% (v/v) commercial bleach for 40 min. After rinsing in sterile water, seeds were imbibed for 4 h in water and were germinated overnight in inverted and sealed petri dishes. Seedlings were plated onto 1% (w/v) agarose containing buffered nodulation medium (BNM; Ehrhardt et al., 1992) and were grown overnight at 24°C in the dark. Seedlings (2–3 cm length) were mounted in custom chambers with 0.5 or 1 mL of liquid BNM for microinjection and imaging. Nodulation factor NodRmIV(C16:2,Ac,S) was purified from Sinorhizobium meliloti strain Rm1021. S-CT4 and purified NodRmIV(C16:2,Ac) (kind gifts of J. Dénarié, Toulouse, France) were solubilized in BNM as 100 nm stocks.

Microinjection and Dual-Dye Imaging

Fura-2 Dextran (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) imaging resulted in unelicited intracellular calcium fluxes within 10 s of exposure to 340 nm light (data not shown) regardless of light exposure levels, dye concentration, or bathing medium (BNM or 100 μm KCl, NaCl2, and MgCl2). Therefore, a single wavelength calcium-sensitive dye was coinjected with a calcium-insensitive dye for monitoring relative changes in intracellular calcium concentration. Growing root hair cells were iontophoretically microinjected with Calcium Green Dextran (10 kD) and Texas Red Dextran (10 kD; Molecular Probes) in a 5:1 (v/v) mixture diluted from 50 mg mL−1 stocks in water. Unbound dye was removed from Dextran dye stock solutions by gel filtration on G-25 spin columns (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) precleaned with water. Salt (100 mm KCl in 5 mm MES, pH 6.5) was added to the dye mixture 1:5 (v/v) to carry charge during the iontophoresis. Cells were allowed to recover for a minimum of 20 min before imaging. Only cells showing rapid cytoplasmic streaming were chosen for imaging.

Cells were imaged with a 40× 0.75 n.a. lens or a 60× 1.0 n.a. water immersion lens on an inverted microscope (TE200; Nikon, Melville, NY). Ratio image pairs, 100-ms exposures with 10 ms of dead time, were collected every 4 s, or every 1 s for the image series in Figure 3, using separate excitation filters and a multipass filter cube (490 ± 110 nm excitation and 530 ± 15 nm emission for Calcium Green; 570 ± 10 nm excitation and 630 ± 20 nm emission for Texas Red; Chroma, Brattleboro, VT) with excitation filters mounted in a dual-filter wheel (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). Images were collected (binned 2 × 2 pixels) with a cooled CCD camera (model 1300; Princeton Instruments, Trenton, NJ) at 12-bit precision through a 1× projection lens (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). Mixing time for Nod factor, estimated from application and mixing of fluorescent dye to medium, was less than 30 s (data not shown). Image acquisition and peripheral device control were automated using Metafluor imaging software (Universal Imaging Corporation, West Chester, PA).

Calcium traces are presented as the unscaled ratio trace and a derivative [(n + 1) − n] trace scaled 2.5× relative to the ratio trace. Due to the variability in the ratio of dyes moved into the cell during iontophoresis and the difference in accrued photobleaching over the duration of the 45- to 60-min experiment, calibration of the ratio values to an external standard or to experimentally manipulated in vivo calcium levels proved unreliable for estimating the magnitude of calcium change in molar quantities (Goddard et al., 2000; Walker et al., 2000). Significant calcium changes preceding the onset of calcium spiking were identified using the following two criteria. To estimate usable dynamic range for calcium changes in the ratio image traces, we measured the mean peak to trough difference during the first 10 min of calcium spiking divided by the sd of the mean of the trace in the >7 min (n> = 105 time points) preceding Nod factor addition. The majority of traces varied between 20:1 and 35:1, dependent mostly upon lamp flicker (increased baseline noise) and the injected dye ratio. All flux responses (e.g. Fig. 1C) had a baseline to peak change greater than 75% of the dynamic range of the initial calcium spikes. The sd taken from the first 7 min of the derivative trace, representing ratio-to-ratio noise and natural variation in the untreated cell, was multiplied by 3.5 (>99% confidence interval) and was displayed (gray line) as a basis for identifying rapid (4-s interval) changes in calcium concentration (i.e. the initiation of calcium flux and spiking responses). Data analysis was performed and figures were created using Matlab v.6.1 (Mathworks, Natick, MA), Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA), and Illustrator 9.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David Ehrhardt, Stephen Smith, and members of the Long laboratory for helpful discussions and suggestions for the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and by the Department of Energy Biosciences Division (grant no. DE–FG03–90ER2001).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.005546.

LITERATURE CITED

- Allen GJ, Chu SP, Schumacher K, Shimazaki CT, Vafeados D, Kemper A, Hawke SD, Tamman G, Tsien RY, Harper JF et al. Alteration of stimulus-specific guard cell calcium oscillations and stomatal closing in Arabidopsis det3 mutant. Nature. 2000;289:2338–2342. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardourel M, Demont N, Debelle F, Maillet F, de Billy F, Prome JC, Denarie J, Truchet G. Rhizobium meliloti lipooligosaccharide nodulation factors: different structural requirements for bacterial entry into target root hair cells and induction of plant symbiotic developmental responses. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1357–1374. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.10.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blume B, Nürnberger T, Nass N, Scheel D. Receptor-mediated increase in cytoplasmic free calcium required for activation of pathogen defense in parsley. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1425–1440. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.8.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boller T. Chemoperception of microbial signals in plant cells. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Mol Biol. 1995;46:189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas L, Feijo JA, Kunkel JG, Sanchez F, Holdaway-Clarke TL, Hepler PK, Quinto C. Rhizobium nod factors induce increases in intracellular free calcium and extracellular calcium influxes in bean root hairs. Plant J. 1999;19:347–352. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas L, Holdaway-Clarke TL, Sanchez F, Quinto C, Feijo JA, Kunkel JG, Hepler PK. Ion changes in legume root hairs responding to Nod factors. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:443–452. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.2.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catoira R, Galera C, de Billy F, Penmetsa RV, Journet EP, Maillet F, Rosenberg C, Cook D, Gough C, Dénarié J. Four genes of Medicago truncatula controlling components of a Nod factor transduction pathway. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1647–1666. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.9.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DR. Medicago truncatula: a model in the making! Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1999;2:301–304. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(99)80053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Koninck P, Schulman H. Sensitivity of CaM kinase II to the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. Science. 1998;279:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5348.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dénarié J, Debelle F, Prome JC. Rhizobium lipo-chitooligosaccharide nodulation factors: signaling molecules mediating recognition and morphogenesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:503–535. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch RE, Lewis RS, Goodnow CC, Healy JI. Differential activation of transcription factors induced by Ca2+ response amplitude and duration. Nature. 1997;386:855–858. doi: 10.1038/386855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch RE, Xu K, Lewis RS. Calcium oscillations increase the efficiency and specificity of gene expression. Nature. 1998;392:933–936. doi: 10.1038/31960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt DW, Atkinson EM, Long SR. Depolarization of alfalfa root hair membrane potential by Rhizobium meliloti Nod factors. Science. 1992;256:998–1000. doi: 10.1126/science.10744524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt DW, Wais R, Long SR. Calcium spiking in plant root hairs responding to Rhizobium nodulation signals. Cell. 1996;85:673–681. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endre G, Kereszt A, Kevei Z, Mihacea S, Kalo P, Kiss GB. A receptor kinase gene regulating symbiotic nodule development. Nature. 2002;417:962–966. doi: 10.1038/nature00842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etzler ME, Kalsi G, Ewing NN, Roberts NJ, Day RB, Murphy JB. A Nod factor binding lectin with apyrase activity from legume roots. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5856–5861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felle HJ. Control of cytoplasmic pH under anoxic conditions and its implications for plasma membrane proton transport in Medicago sativa root hairs. J Exp Bot. 1996;47:967–973. [Google Scholar]

- Felle HH, Hepler PK. The cytosolic Ca2+ concentration gradient of Sinapis alba root hairs as revealed by Ca2+-selective microelectrode tests and fura-Dextran ratio imaging. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:39–45. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felle HH, Kondorosi E, Kondorosi A, Schultze M. Nod signal-induced plasma membrane potential changes in alfalfa root hairs are differentially sensitive to structural modifications of the lipochitooligosaccharide. Plant J. 1995;7:939–947. [Google Scholar]

- Felle HH, Kondorosi E, Kondorosi A, Schultze M. Rapid alkalinization in alfalfa root hairs in response to rhizobial lipochitooligosaccharide signals. Plant J. 1996;10:295–301. [Google Scholar]

- Felle HH, Kondorosi E, Kondorosi A, Schultze M. The role of ion fluxes in Nod factor signaling in Medicago sativa. Plant J. 1998;13:455–463. [Google Scholar]

- Felle HH, Kondorosi E, Kondorosi A, Schultze M. Elevation of the cytosolic free (Ca2+) is indispensable for the transduction of the Nod factor signal in alfalfa. Plant Physiol. 1999a;121:273–279. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.1.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felle HH, Kondorosi E, Kondorosi A, Schultze M. Nod factors modulate the concentration of cytosolic free calcium differently in growing and non-growing root hairs of Medicago sativa L. Planta. 1999b;209:207–212. doi: 10.1007/s004250050624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felle HH, Kondorosi E, Kondorosi A, Schultze M. How alfalfa root hairs discriminate between Nod factors and oligochitin elicitors. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:1373–1380. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.3.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard H, Manison NFH, Tomos D, Brownlee C. Elemental propagation of calcium signals in response-specific patterns determined by environmental stimulus strength. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1932–1937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.020516397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedhart J, Hink MA, Visser AJWG, Bisseling T, Gadella TWJ., Jr In vivo fluorescence correlation microscopy (FCM) reveals accumulation and immobilization of Nod factors in root hair cell walls. Plant J. 2000;21:109–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidstra R, Bisseling T. Nod factor-induced host responses and mechanisms of Nod factor action. New Phytol. 1996;133:25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Heidstra R, Geurts R, Franssen H, Spaink HP, van Kammen A, Bisseling T. Root hair deformation activity of nodulation factors and their fate on Vicia sativa. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:787–797. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.3.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Llopis J, Whitney M, Zlokarnik G, Tsien RY. Cell-permeant caged InsP3 ester shows that Ca2+ spike frequency can optimize gene expression. Nature. 1998;392:936–941. doi: 10.1038/31965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligterink W, Kroj T, zur Nieden U, Hirt H, Scheel D. Receptor-mediated activation of a MAP kinase in pathogen defense of plants. Science. 1997;276:2054–2057. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SR. Rhizobium symbiosis: Nod factors in perspective. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1885–1898. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAinsh MR, Webb AAR, Taylor JE, Hetherington AM. Stimulus-induced oscillations in guard cell cytosolic free calcium. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1207–1219. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.8.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami E, Kouchi H, Carlson RW, Cohn JR, Kolli VK, Day RB, Ogawa T, Stacey G. Cooperative action of lipo-chitin nodulation signals on the induction of the early nodulin, ENOD2, in soybean roots. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1996;9:574–583. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-9-0574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nürnberger T, Nennstiel D, Jabs T, Sacks WR, Hahlbrock K, Scheel D. High affinity binding of fungal oligopeptide elicitor to parsley plasma membranes triggers multiple defense responses. Cell. 1994;78:449–460. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd GED, Mitra RM, Wais RJ, Long SR. Evidence for structurally specific negative feedback in the Nod factor signal transduction pathway. Plant J. 2001;28:191–199. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penmetsa RV, Cook DR. A legume ethylene-insensitive mutant hyperinfected by its rhizobial symbiont. Science. 1997;275:527–530. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5299.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeis T, Piedras P, Zhang S, Klessig DF, Hirt H. Rapid Avr9- and Cf-9-dependent activation of MAP kinases in tobacco cell cultures and leaves: convergence of resistance gene, elicitor, wound, and salicylate responses. Plant Cell. 1999;11:273–287. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.2.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders D, Brownlee C, Harper JF. Communicating with calcium. Plant Cell. 1999;11:691–706. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.4.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheel D. Resistance response physiology and signal transduction. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1998;1:305–310. doi: 10.1016/1369-5266(88)80051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wais RJ, Galéra C, Oldroyd G, Catoira R, Penmetsa RV, Cook D, Gough C, Dénarié J, Long S. Genetic analysis of calcium spiking responses in nodulation mutants of Medicago truncatula. Proc Natl Aacd Sci USA. 2000;97:13407–13412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230439797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker SA, Viprey V, Downie JA. Dissection of nodulation signaling using pea mutants defective for calcium spiking induced in root hairs by Nod factors and chitin oligomers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13413–13418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230440097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Shah J, Klessig DF. Signal perception and transduction in plant defense responses. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1621–1639. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]