Abstract

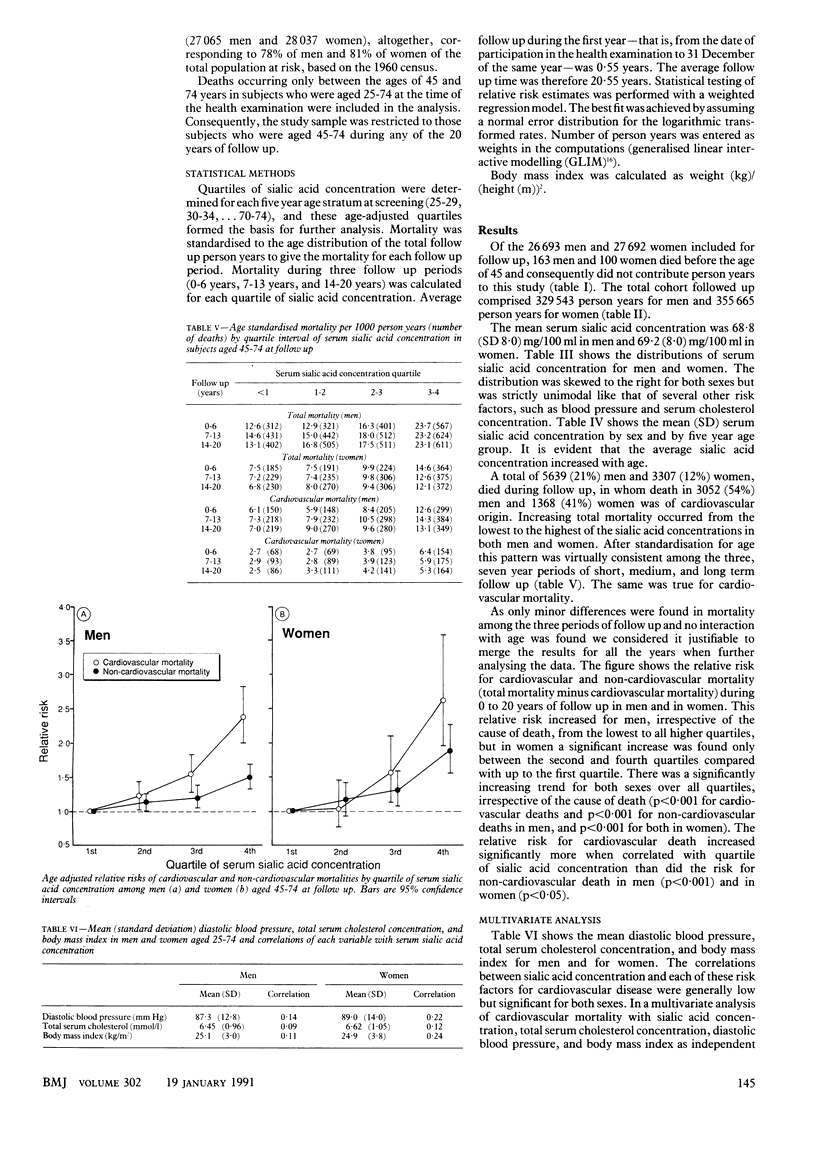

OBJECTIVE--To determine whether serum sialic acid concentration may be used to predict short and long term cardiovascular mortality. DESIGN--Prospective study on all men and women who had their serum sialic acid concentration measured as part of a general health survey in 1964 or in 1965. All were followed up for an average of 20.5 years. SETTING--Geographical part of the county of Värmland, Sweden. SUBJECTS--Residents in the area participating in a health check up in 1964-5 (27,065 men and 28,037 women), of whom 372 men (169 with incomplete data and 203 lost to follow up) and 345 women (143 and 202 respectively) were excluded; thus 26,693 men and 27,692 women entered the study. The study sample was restricted to subjects aged 40-74 during any of the 20 years' follow up. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Serum sialic acid concentration, serum cholesterol concentration, diastolic blood pressure, body mass index at the general health survey visit; cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular deaths during three periods of follow up (0-6 years, 7-13 years, and 14-20 years), according to the Swedish mortality register, in subjects aged 45-74. RESULTS--Mean serum sialic acid concentration (mg/100 ml) was 68.8 (SD 8.0) for men and 69.2 (8.0) for women; the average concentration increasing with age in both sexes. A total of 5639 (21%) men and 3307 (12%) women died during the follow up period, in whom death in 3052 (54%) men and 1368 (41%) women was from cardiovascular causes. During short (0-6 years), medium (7-13 years), and long (14-20 years) term follow up the relative risk of death from cardiovascular disease increased with increasing serum sialic acid concentration. The relative risk (95% confidence interval) associated with the highest quartile of sialic acid concentration compared with the lowest quartile was 2.38 (2.01 to 2.83) in men and 2.62 (1.93 to 3.57) in women. Similar results were found for deaths from non-cardiovascular disease with relative risks of 1.50 (1.34 to 2.68) in men and 1.89 (1.57 to 2.28) in women, but these relative risks were significantly lower than those for deaths from cardiovascular disease (p less than 0.001 and p less than 0.005 respectively). In multivariate analysis of total mortality and of cardiovascular mortality with sialic acid concentration, serum cholesterol concentration, diastolic blood pressure, and body mass index as independent variables the impact of sialic acid concentration was virtually the same as in univariate analysis. CONCLUSION--Serum sialic acid concentration is a strong predictor of cardiovascular mortality. A possible explanation of these findings is that the serum sialic acid concentration may reflect the existence or the activity of an atherosclerotic process, and this may warrant further investigation.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Krolikowski F. J., Reuter K., Waalkes T. P., Sieber S. M., Adamson R. H. Serum sialic acid levels in lung cancer patients. Pharmacology. 1976;14(1):47–51. doi: 10.1159/000136578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade T. W., North W. R., Chakrabarti R., Stirling Y., Haines A. P., Thompson S. G., Brozovié M. Haemostatic function and cardiovascular death: early results of a prospective study. Lancet. 1980 May 17;1(8177):1050–1054. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91498-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrén S., Vesterberg O. The N-acetylneuraminic acid content of five forms of human transferrin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989 Feb 2;994(2):161–165. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(89)90155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnamurthy B., Berenson G. S., Pargaonkar P. S., Voors A. W., Srinivasan S. R., Plavidal F., Dolan P., Dalferes E. R., Jr Serum-free and protein-bound sugars and cardiovascular complications in diabetes mellitus. Lab Invest. 1976 Feb;34(2):159–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SVENNERHOLM L. Quantitative estimation of sialic acids. II. A colorimetric resorcinol-hydrochloric acid method. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1957 Jun;24(3):604–611. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(57)90254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwick H. G., Haupt H. Properties of acute phase proteins of human plasma. Behring Inst Mitt. 1986 Jun;(80):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamberger R. J. Serum sialic acid in normals and in cancer patients. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1984 Oct;22(10):647–651. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1984.22.10.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shvarts L. S., Paukman L. I. Diabeticheskie angiopatii i obmen mukopolisakharidov. Probl Endokrinol (Mosk) 1971 Jan-Feb;17(1):37–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart J., George A. J., Davies A. J., Aukland A., Hurlow R. A. Haematological stress syndrome in atherosclerosis. J Clin Pathol. 1981 May;34(5):464–467. doi: 10.1136/jcp.34.5.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Succari M., Foglietti M. J., Percheron F. Glycoprotéines perchlorosolubles et infarctus du myocarde: modifications de la fraction glycannique. Pathol Biol (Paris) 1982 Mar;30(3):151–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swahn E., von Schenck H., Wallentin L. Plasma fibrinogen in unstable coronary artery disease. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1989 Feb;49(1):49–54. doi: 10.3109/00365518909089077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniuchi K., Chifu K., Hayashi N., Nakamachi Y., Yamaguchi N., Miyamoto Y., Doi K., Baba S., Uchida Y., Tsukada Y. A new enzymatic method for the determination of sialic acid in serum and its application for a marker of acute phase reactants. Kobe J Med Sci. 1981 Jun;27(3):91–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Törnberg S. A., Holm L. E., Carstensen J. M., Eklund G. A. Cancer incidence and cancer mortality in relation to serum cholesterol. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989 Dec 20;81(24):1917–1921. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.24.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Törnberg S. A., Holm L. E., Carstensen J. M., Eklund G. A. Risks of cancer of the colon and rectum in relation to serum cholesterol and beta-lipoprotein. N Engl J Med. 1986 Dec 25;315(26):1629–1633. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612253152601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma R., Michos G. A., Varma R. S., Brown R. D., Jr The protein-bound carbohydrates of seromucoid from normal human serum. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1983 May;21(5):273–277. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1983.21.5.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsen L., Svärdsudd K., Korsan-Bengtsen K., Larsson B., Welin L., Tibblin G. Fibrinogen as a risk factor for stroke and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1984 Aug 23;311(8):501–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408233110804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAK B., DICKENMAN R. C., WHITE E. G., BURNETT H., CHERNEY P. J. Rapid estimation of free and total cholesterol. Am J Clin Pathol. 1954 Nov;24(11):1307–1315. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/24.11_ts.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]