Abstract

We investigated the membrane properties and dominant ionic conductances in the plasma membrane of the calcifying marine phytoplankton Coccolithus pelagicus using the patch-clamp technique. Whole-cell recordings obtained from decalcified cells revealed a dominant anion conductance in response to membrane hyperpolarization. Ion substitution showed that the anion channels were selective for Cl− and Br− over other anions, and the sensitivity to the stilbene derivative 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid, ethacrynic acid, and Zn2+ revealed a pharmacological profile typical of many plant and animal anion channels. Voltage activation and kinetic characteristics of the C. pelagicus Cl− channel are consistent with a novel function in plants as the inward rectifier that tightly regulates membrane potential. Membrane depolarization gave rise to nonselective cation currents and in some cases evoked action potential currents. We propose that these major ion conductances play an essential role in membrane voltage regulation that relates to the unique transport physiology of these calcifying phytoplankton.

Marine phytoplankton are key primary producers contributing as much as 40% of annual global carbon assimilation. Ion and nutrient transport across the plasma membrane of such unicellular marine algae is of central importance in maintaining cytoplasmic homeostasis and productivity in the marine environment. Despite their global importance, progress in understanding membrane transport mechanisms in marine phytoplankton has been slow.

The calcifying coccolithophorid phytoplankton such as Emiliania huxleyi and Coccolithus pelagicus often form massive monospecific blooms in oceanic waters that cover a total area of up to 1.4 million km2 annually (Brown and Yoder, 1994). They are responsible for forming extensive sedimentary beds of calcite and are considered to be the most significant producers of CaCO3 on Earth with a potential significant impact on global biogeochemical cycles and climate change (Riebesell et al., 2000; Zondervan et al., 2001) by contributing to carbon sequestration in ocean sediment and CO2 and dimethyl sulfide fluxes between the ocean and atmosphere. Although the ecophysiology of coccolithophores has been extensively studied, we know very little about the regulation of the underlying cellular processes during calcification.

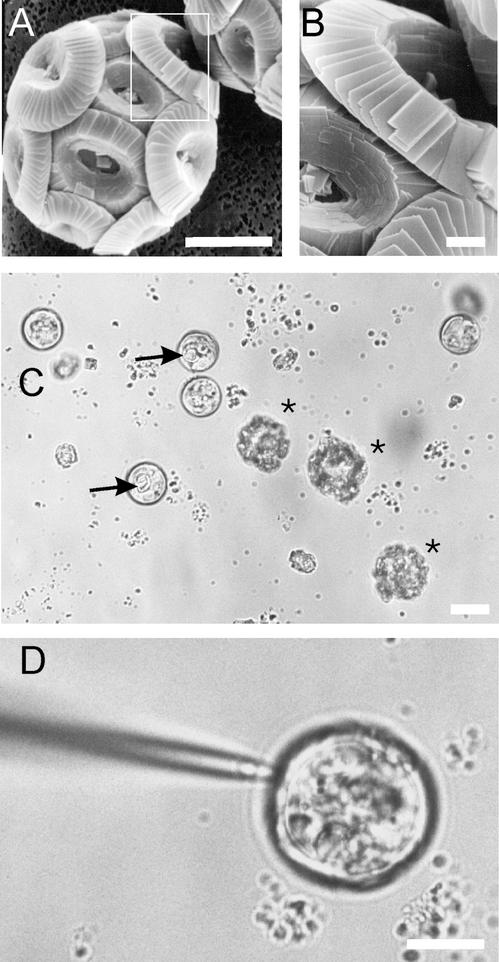

Most calcifying plants and algae do so extracellularly, however coccolithophores are unique in that calcification occurs intracellularly. Plates or coccoliths are assembled in a specialized Golgi-derived coccolith vesicle and are secreted onto the cell surface where they interlock to form a shell or coccosphere (Fig. 1, A and B; for reviews, see Westbroek et al., 1984; Paasche, 2001). Coccogenesis is a highly regulated process and depends on a continuous flux of Ca2+ and dissolved inorganic carbon (Ci) most likely as HCO3− (Buitenhuis et al., 1999; Berry et al., 2002) from the external medium into the coccolith vesicle. The molar fluxes of Ca2+ and Ci into the coccolith vesicle can equal the molar flux of photosynthetically fixed carbon (i.e. calcification/photosynthesis ratios of unity). Characterization of the ion transport mechanisms in the plasma membrane of coccolithophores is essential to understand the precise mechanisms and functional significance of calcification with respect to environmental physiology.

Figure 1.

Patch clamping C. pelagicus. A, Scanning electron micrograph showing a C. pelagicus cell with coccosphere of CaCO3 coccoliths; scale bar = 10 μm. B, Enlargement of the box outlined in A to show detail of coccolith; scale bar = 1 μm. C, Light micrograph to illustrate both EGTA decalcified and calcified C. pelagicus cells (marked with *). Arrows indicate a partially formed coccolith that can be seen within a decalcified cell; scale bar = 10 μm. D, Patch-clamp pipette forming a seal on decalcified C. pelagicus cell; scale bar = 10 μm.

There is currently no information available concerning the electrical and ionic properties of the coccolithophore plasma membrane. To address this need, we have successfully applied the patch-clamp technique to investigate the primary membrane conductances in C. pelagicus cells. This provides a basis for understanding the membrane transport properties of these organisms and from which to identify pathways for and regulation of Ca2+ and Ci entry that is essential for calcification. Our results reveal a surprising regulation of membrane potential by a large Cl− inward-rectifying conductance, which contrasts with the dominant K+-rectifying properties reported for higher plant cells and marine diatoms and may reflect the unique transport requirements of this calcifying unicell.

RESULTS

Cell Isolation

The decalcification procedure produced intact cells with a clean plasma membrane on which high-resistance seals (1.34 GΩ ±0.2, n = 216) could be obtained routinely with a patch pipette (Fig. 1). Decalcified cells remained viable, started to recalcify within hours, and after 2 to 3 d in culture, generated a complete layer of coccoliths (data not shown). Whole-cell recordings gave a mean cell capacitance of 7.6 pF (±0.2, n = 174), which for an average cell diameter of 15 μm corresponds to a specific membrane capacitance of 1.07 μF cm−2.

Membrane Potential Is Sensitive to Cl− But Not K+

Zero current membrane potential (Vm) measurements were made in whole-cell current clamp mode under various internal and external ionic conditions (Table I). The K+ sensitivity of Vm was determined by perfusing 0.8 and 8 mm KCl-artificial seawater (ASW) over cells under current clamp with an intracellular solution containing 80 mm KCl. There was no significant change in Vm for this 10-fold change in external K+ concentration (Table I). However, Vm was highly sensitive to changes in external and internal Cl− concentration, and Vm settled at or close to the calculated Cl− equilibrium potential for each treatment (Table I).

Table I.

Cl− dependence of Vm and anion current reversal potential

| [KCl] in Pipette | [KCl] in Bath ([K+] / [Cl-]) | Measured Vm | Calculated ECl | Calculated EK | ReversalPotential of Inward Current | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm | mV | mV | mV | mV | ||

| 80 | 0.8/543 | −29± 1 | −38 | −120 | ND | 6 |

| 80 | 8/550 | −29± 1 | −39 | −63 | −41 ± 1 | 29 |

| 8 | 8/550 | −58± 2 | −58 | −9 | −62 ± 4 | 10 |

| 400 | 8/550 | −3± 1 | −6 | −99 | −8 ± 1 | 20 |

Vm and reversal potential for the hyperpolarization-activated inward current are given for a number of different intracellular and extracellular solutions. KCl was the major salt in the pipette solution (see “Materials and Methods”). Concentrations for total K+ and Cl− in the bath solution are given. ECl and EK are the calculated equilibrium potentials for Cl− and K+, respectively, using ion activities. ND, Not determined; ses are given.

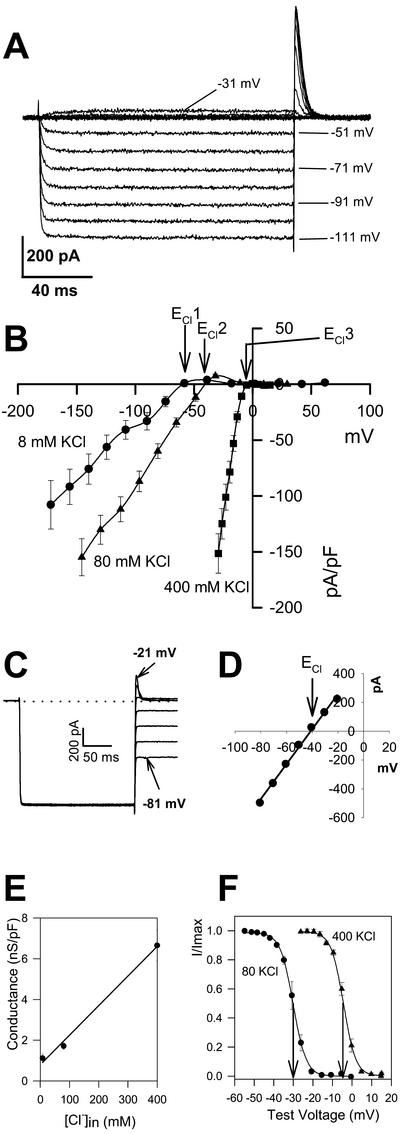

A Voltage-Dependent Cl− Current Is Activated by Hyperpolarization

Whole-cell voltage clamp recordings revealed a large conductance that was activated by hyperpolarization in every cell tested (n = 144; Fig. 2A). The reversal potential of this current coincided precisely with the ECl when 8, 80, and 400 mm KCl were used in the recording pipette (Fig. 2B; Table I), showing that this current is an anion current. The reversal of the anion current at ECl was confirmed with tail current analysis (Fig. 2, C and D). The conductance of the anion current was strongly dependent on the internal Cl− concentration (Fig. 2E), increasing with increased intracellular Cl− concentration. Reversal of the anion current was insensitive to substitution of intracellular K+ for Cs+ (Table II).

Figure 2.

Hyperpolarization-activated anion current is mediated by Cl− channels. A, Typical currents activated by a series of hyperpolarizing voltage pulses. The pipette contained 80 mm KCl, bath solution was 2 mm SO42− ASW. Cell capacitance was 5 pF, and seal resistance was 5.2 GΩ. B, Current-voltage curves for a series of intracellular KCl concentrations. For each concentration, the reversal potential of the current shifts according to the calculated ECl indicated as ECl1, ECl2, and ECl3 for 8, 80, and 400 mm intracellular KCl, respectively. Each curve is the average of the current-voltage responses from at least 10 cells. C, Tail current analysis with 80 mm KCl in the pipette and 2 mm SO42− ASW in the bath. The Cl− current was activated by a step to −111 mV followed by the test voltage as indicated. Cell capacitance was 9 pF, and seal resistance was 4 GΩ. D, Tail currents from traces in C plotted against test voltage reveal a reversal of −41 mV (ECl = −39 mV). E, Relationship between conductance and intracellular Cl− concentration, derived from the slope of the Cl− current with different intracellular KCl concentrations; the same cells as in B were used. F, Normalized tail current-voltage activation curves for 400 and 80 mm intracellular KCl and 2 mm SO42− ASW (n = 4 for each curve). Boltzmann functions fitted to these curves reveal half-activation voltages of −4.5 and −30 mV, respectively, indicated by the arrows (also see Table III).

Table II.

Effect of anion substitution on Cl− current

| Primary Salt in Pipette | Reversal Potential of Anion Current | n | Calculated ECl |

|---|---|---|---|

| mV | mV | ||

| 80 mm CsCl | −41 ± 2 | 30 | −40 |

| 80 mm Cs-Glu | −70 ± 2 | 28 | −68 |

| 80 mm CsNO3 | −61 ± 2 | 11 | −60 |

| 400 mm KCl | −8 ± 1 | 20 | −6 |

| 400 mm KBr | −3 ± 3 | 9 | −95 |

| 80 mm K-Glu | −75 ± 3 | 10 | −69 |

Reversal potential of the hyperpolarization-activated inward anion current for a number of different intracellular pipette solutions. Extracellular solution was normal ASW. All pipette solutions contained 5 mm MgCl2 (see “Materials and Methods”). ses are given.

Voltage-activation curves fitted to a Boltzmann function revealed shifts in the voltage activation of the Cl− channel that closely followed ECl. To assess the voltage dependence of gating, activation curves were derived from cells bathed in 2 mm SO42− ASW (to enable more accurate tail current resolution, see below). The half-activation voltage (V0.5) was −4.4 mV for a pipette solution containing 400 mm KCl and shifted negative to −30.1 mV with 80 mm KCl in the pipette (Fig. 2F; Table III). This is equivalent to a 51-mV shift in V0.5 for a 10-fold change in internal Cl− concentration. Activation of the Cl− current was extremely sensitive to voltage. For example, with 400 mm KCl pipette solution and 2 mm SO42− ASW in the bath, only a 3-mV change in membrane voltage was required to change the current e-fold. This is also illustrated by the large gating charge value (δ, see Table III).

Table III.

Boltzmann parameters for voltage activation of Cl− current

| KCl in Pipette | SO4− in Bath | δ | S | V0.5 | Calculated ECl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm | mm | mV | mV | ||

| 400 | 2 | 8.02 | 3.15 | −4.4 | −6 |

| 80 | 2 | 7.68 | 3.3 | −30.1 | −39 |

Summary of the effect of intracellular Cl− on the voltage activation of the inward anion rectifier. The concentrations of major salt in the pipette and the SO42− in the extracellular ASW are given. S, Slope of voltage activation; δ, gating charge (see “Materials and Methods”).

The activation kinetics of the Cl− current were explored by fitting exponential curves to the initial non-steady-state currents stimulated by hyperpolarizing membrane pulses (Fig. 3). Activation was very rapid once the threshold voltage was reached with an average time constant of 2.5 ms (± 0.05, n = 8) for currents activated by a voltage step from −30 to −45 mV with 80 mm KCl in the pipette. The activation of the Cl− current exhibited a voltage-dependent relationship whereby progressively more negative step voltages resulted in even faster current activation (Fig. 3B). The Cl− current also exhibited rapid and voltage-dependent deactivation. Tail currents recorded in 2 mm SO42− ASW (Fig. 3C) deactivated more rapidly as the clamp command step became more positive (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Activation and deactivation kinetics of the C. pelagicus Cl− current. A, Inward Cl− currents activated by step hyperpolarization from a holding potential of −30 mV. Activation kinetics were obtained by fitting a single exponential curve to each trace (solid lines). Pipette solution contained 80 mm KCl, and bath solution contained 16 mm SO42− ASW. B, Graph of activation time constant and hyperpolarizing test voltage for eight cells under the same recording conditions as illustrated by A. C, Example of deactivating tail currents from which deactivation time constants were derived. Cl− currents were activated by hyperpolarizing the membrane to −110 mV followed by a sequence of deactivation voltage steps. Pipette solution contained 80 mm KCl and bath consisted of 2 mm SO42− ASW to resolve tail currents and to enable curve fitting of a single exponential to the deactivating current. D, Graph to illustrate deactivation time constant versus repolarization tail voltage. Deactivation time constants were derived from four cells under the same conditions illustrated in C. ses are indicated.

The selectivity of the conductance to other anions was investigated by substituting intracellular Cl− with Glu or nitrate (Table II). For each treatment, the inward current reversed at the equilibrium potential for Cl−, showing that the anion current is highly selective for Cl− over other larger anions. The relative permeability to Br− was investigated in the same manner and revealed a reversal potential between ECl and the calculated equilibrium potential for Br− (Table II). The relative permeability sequence of the anion current was therefore Cl− = Br− with no significant permeability to Glu NO3−. However, the whole-cell conductance of the anion current when Br− was the main permeating anion (i.e. pipette contained 400 KBr) was 1.39 ns/pF (± 0.38, n = 8), significantly lower than for the same concentration of KCl (6.65 ns/pF ±0.76, n = 8; see Fig. 2E).

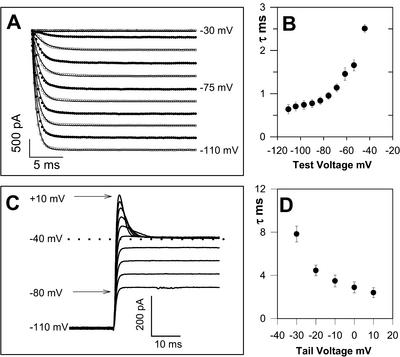

The Cl− Current Rectifies in the Presence of External Sulfate

The presence of external SO42− had a dramatic influence on the rectifying properties of the Cl− current. In the absence of SO42− in the external medium, the conductance, once activated, passed both outward and inward current. This can be seen from the voltage-activated outward current and large persistent outward tail currents observed after current activation by a hyperpolarizing voltage pulse (Fig. 4A). Bath perfusion with 2 mm SO42− ASW caused a partial block of the voltage-activated outward current and corresponding tail currents (Fig. 4B) and partial rectification. Bath perfusion with 16 mm SO42− ASW abolished the voltage-activated outward current and outward tail currents resulting in full rectification (Fig. 4C). In contrast to the dramatic effects of external SO42− on the Cl− current, substitution of MgCl2 with MgSO4 in the recording pipette had no significant effect (n = 5; data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effect of SO42− on Cl− current. A, Current traces (left) and corresponding steady-state current-voltage curve (right) for a family of hyperpolarizing voltage pulses in SO42−-free ASW. The intracellular solution contained 40 mm KCl. Cell capacitance was 6 pF, and seal resistance was 2 GΩ. Note the outward Cl− current at potentials positive of ECl and the prolonged tail current. B, The same cell as in A except in the presence of 2 mm SO42− ASW. C, The same cell as in A except in the presence of normal 16 mm SO42− ASW. Note the disappearance of outward Cl− current and tail current.

Pharmacology and Regulation of the Cl− Conductance

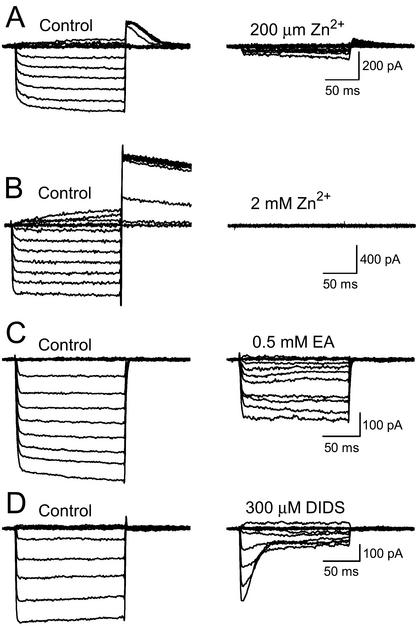

The voltage-dependent inward Cl− current was reversibly blocked by external (200 μm, n = 9; Fig. 5A) but not internal Zn2+ (5 mm, n = 4). Full block was achieved by including 0.5 mm Zn2+ in the bath solution (n = 19). In SO42−-free media, Zn2+ ions blocked the outward voltage-activated and tail currents in addition to the inward component of the Cl− current (Fig. 5B). The Cl− current was blocked by both ethycrynic acid (n = 3) and the stilbene derivative 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (n = 5) in the external medium (Fig. 5, C and D). In all of the above treatments, the Cl− current recovered on perfusion of fresh external media without inhibitor (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Cl− channel pharmacology. A, Block of inward and tail Cl− current by perfusion of 200 μm ZnCl2 in the external ASW medium. B, Complete block of Cl− current by 2 mm ZnCl2 in the ASW medium. The pipette solution contained 400 mm KCl, and the external solution was SO42−-free ASW. Note the tail current is also completely abolished by Zn2+. C, The Cl− current is blocked by 0.5 mm ethacrynic acid (EA). The pipette solution contained 80 mm CsCl and the external solution was 16 mm SO42− ASW. D, Cl− current block by 300 μm 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid. The pipette contained 80 mm Cs-Glu solution, and the external medium was 16 mm SO42− ASW.

Because algal and higher plant Cl− channels are known to be sensitive to pH, ATP, and Ca2+ (Barbier-Brygoo et al., 2000), their effects were tested on the coccolithophore Cl− current. The presence of up to 5 mm ATP in the pipette had no significant effect on the Cl− current (n = 5). Altering external pH from 8.0 to 5.5 had no significant effect (n = 3). Altering internal free Ca2+ from <10 nm to 1 μm had no effect on the Cl− current (n = 7).

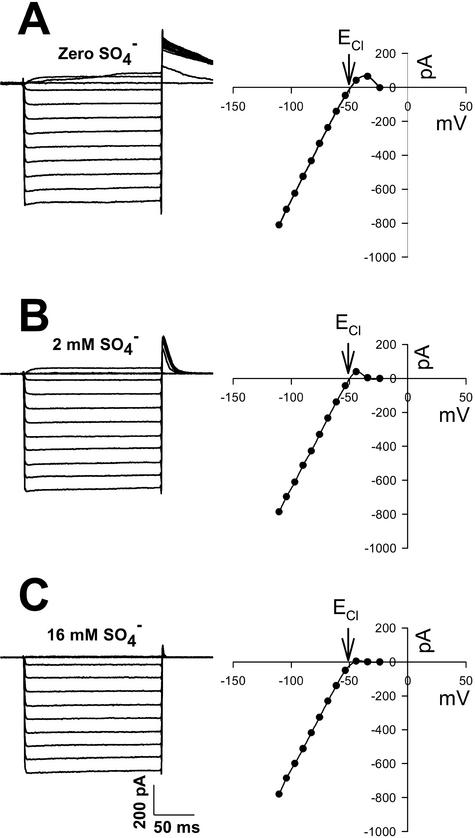

Depolarization-Activated Cation Currents

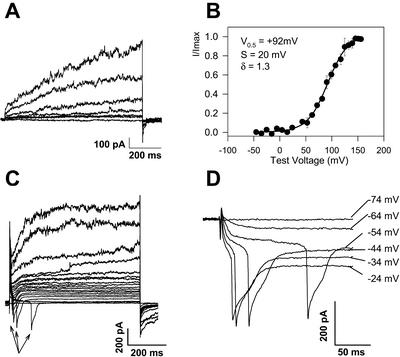

Depolarization-activated currents were investigated by selecting internal [Cl−] such that Cl− currents were not activated at the required holding voltage or by blocking the Cl− current with Zn+. With 2 mm ZnCl2 in the bath, complete block of the Cl− current was achieved (see Fig. 4B), and the cell could be clamped at voltages more negative than ECl. On achieving block by Zn+ of the inward Cl− current, membrane depolarization elicited a slowly activating outward current (Fig. 6A). With 400 mm KCl in the pipette and 2 mm Zn+-ASW in the bath, the outward current activated from 0 mV and exhibited a V0.5 of +92 mV, voltage sensitivity of 20 mV for an e-fold change in current and gating charge of 1.3 (Fig. 6B). Tail currents reversed significantly more positive than EK at −11 mV (±3, n = 3) and −17 mV (±3, n = 4) for pipette solutions containing 80 or 400 mm KCl, respectively (data not shown).

Figure 6.

C. pelagicus plasma membrane currents activated by depolarization. A, Depolarizing voltages activate time-dependent outward currents with rapid deactivation. The pipette contained 400 mm KCl intracellular solution. B, Voltage activation characteristics of the outward cation current with pipette containing 400 mm KCl (n = 3). The activation curve is fitted with a Boltzmann function (see “Materials and Methods”) showing a V0.5 of +90 mV. C, An “action potential”-like current is stimulated by depolarization. A non-leak subtracted current responses to a family of depolarizing voltage pulses from −74 mV to +126 mV. Seal resistance was 0.4 GΩ, and cell capacitance 7.5 pF. Pipette solution was 80 mm K-Glu. Examples of the evoked inward current spikes are marked with arrows. D, Expanded leak subtracted traces from A showing the voltage-dependent delay in activation of the action potential spike and detail of the time course of the action potential current.

In addition to the slow outward currents, fast transient voltage-activated inward current spikes with a threshold between −50 and +10 mV were observed to a varying degree depending of the batch of cells. No action potential currents were detected in some batches, whereas in others, up to 70% of the cells exhibited this excitability (Fig. 6C). Under conditions of free-running membrane potential, the consequence of activating the action current would lead to a regenerative action potential. Action potential currents were observed in experiments where the recording pipette contained KCl, K-Glu, or CsCl. In every cell exhibiting excitability, the evoked currents disappeared within 3 to 45 min of achieving the whole-cell recording. The evoked current consisted of a rapid inward phase (τ = 1.1 ms, ±0.1) followed by a slower outward phase. The entire evoked current transient was complete within 63 ms (±3; Fig. 6, C and D).

DISCUSSION

The voltage and kinetic characteristics of the Cl− current of C. pelagicus show unique properties that distinguish it from anion currents of higher plants and other algae in several ways. First, it is activated by negative voltages, has a very steep voltage dependence and fast activation and deactivation kinetics, and rectifies strongly in the presence of normal seawater SO42− concentrations. In contrast, with few exceptions higher plant plasma membrane anion channels are activated by depolarization and can mediate anion influx at voltages more positive than the anion equilibrium potential (Barbier-Brygoo et al., 2000). Although anion channels activated by hyperpolarizing membrane potential have been described (Terry et al., 1991; Barbara et al., 1994; Elzenga and VanVolkenburgh, 1997), full functional characterization remains limited.

Higher plant anion channels activated by depolarization can be broadly divided into those that exhibit either fast (millisecond) or slow (second) activation kinetics. The plasma membrane anion channels of the guard cell have been studied in detail (Keller et al., 1989; Schroeder and Keller, 1992; Hedrich, 1994; Dietrich and Hedrich, 1998). The fast activation and rapid inactivation of R-type guard cell anion channels reflect a likely role in transient stabilization of Vm, whereas the slow kinetics of activation and inactivation and the wide range of anions transported by the S-type channel are properties suited to longer term solute loss during turgor regulation. Unlike most algal and higher plant cell walls, the coccolithophorid coccosphere consisting of interlocking calcite plates does not present a significant mechanical barrier for turgor generation, and coccolithophores are regarded as iso-osmotic with the seawater medium. Moreover, in the stable oceanic ionic environment (Kennish, 2001), coccolithophores are not normally subjected to large rapid fluctuations in salinity. It is unlikely therefore that the primary role of the Cl− channel described here is to mediate large osmoregulatory ion fluxes in response to external osmotic changes. Rather, the rapid kinetics of the C. pelagicus Cl− channel indicates a role in membrane potential regulation (see below).

A second characteristic of the C. pelagicus Cl− current that differs from higher plant anion channels is the insensitivity to modulatory factors. For example, guard cell plasma membrane anion channels are activated in a Ca2+- and ATP-dependent manner and are sensitive to intra- and extracellular pH (SchulzLessdorf et al., 1996), whereas the C. pelagicus Cl− channel was insensitive to these factors. Furthermore, guard cell anion channels are also modulated by organic acids (Hedrich et al., 1994) and the hormone abscisic acid, demonstrating the essential role these channels play in integrating responses to metabolic state and hormonal signaling with plasma membrane solute fluxes. Metabolic regulation of ion channels has also been demonstrated in Chara spp., where pH modulated anion fluxes play a key role in cytosolic pH regulation (Johannes et al., 1998). The insensitivity of the Cl− channel in C. pelagicus to ATP, intracellular Ca2+, and extracellular pH indicates that this channel is primarily regulated by membrane voltage and the Cl− gradient across the plasma membrane although there may be other, as yet uncharacterized regulatory mechanisms.

The third contrasting characteristic of C. pelagicus anion channels is their high selectivity for Cl− over larger anions. Anion channels in broad bean (Vicia faba) guard cells (Dietrich and Hedrich, 1998) and Arabidopsis hypocotyl cells (Thomine et al., 1997; Frachisse et al., 2000) are significantly permeant to NO3−. Hypocotyl cells from Arabidopsis are also permeant to SO42−, supporting a role in the transport of mineral nutrients (Frachisse et al., 1999). In contrast, the fast inward rectifier Cl− channels of C. pelagicus are permeant to other halides but impermeant to NO3− and SO42−. It is clear therefore that the Cl− channel in C. pelagicus cannot be involved in uptake or release of these mineral nutrients. This is not unexpected because these algal unicells cells bloom in ocean waters that typically contain <30 μm NO3− and 2 μm PO32−, conditions, which impose the requirement of strict conservation of cellular nutrient pools acquired actively against such a large gradient.

The C. pelagicus Cl− current unusually displays features that closely resemble the classic K+ inward rectifier (Hille, 2001). These are: (a) opening at negative voltages with a steep voltage dependence, (b) gating and conductance dependent on the concentration of permeant ion, shifting toward the new equilibrium, and (c) fast activation kinetics. These characteristics are also common to animal ClC0 and ClC1-type Cl− channels, which play a key role in stabilization of membrane potential (Jentsch et al., 2002, and refs. therein). The properties of the C. pelagicus Cl− current together with the observations that the current was highly selective, did not exhibit rundown, and was present in every cell, lead us to conclude that it functions as the primary plasma membrane inward rectifier, playing a fundamental role in the regulation of membrane potential and membrane excitability in this planktonic alga. Moreover, the dependence of voltage activation on intracellular Cl− shows that the gating is coupled to the Cl− electrochemical gradient, supporting the contention that ECl dominates the membrane potential in C. pelagicus. This is in marked contrast to the marine diatom Cosinodiscus wailesii, where both current clamp and voltage clamp recordings indicate that the major inward-rectifying conductance is K+ selective and membrane potential is dominated by EK (Gradmann and Boyd, 1999). Interestingly, a single-channel study of Valonia utricularis protoplasts has recently revealed a Cl− channel with remarkably similar properties to the Cl− conductance described here for C. pelagicus (Heidecker et al., 1999), raising the possibility that a dominant Cl− inward rectifier could be present in a range of marine algae.

Effects of external SO42− ions on the rectifying behavior of the Cl− current imply that the presence of SO42−, a major conservative ionic component of seawater (28–30 mm; Kennish, 2001) confers specific functional properties on the channel. The lack of effect of cytosolic SO42− shows that it influences channel behavior by binding to an external site. However, external SO42− does not affect Cl− efflux, therefore the SO42−-binding site must be distinct from the channel pore or permeation pathway. In the absence of SO42−, the Cl− channel, once activated, can pass Cl− ions both into and out of the cell. External SO42− blocks Cl− influx, probably by accelerating deactivation of the current such that tail currents are extremely brief. The presence of SO42− in seawater therefore enhances the rectification of the Cl− current by preventing any significant Cl− influx when the channel is activated. A further key role for the Cl− channel in C. pelagicus most likely lies in charge balance for other transport processes. Of particular significance is the likely balance of charge necessary during Ci uptake for calcification. Several reports suggest HCO3− may be used as an external Ci substrate for calcification (Buitenhuis et al., 1999; Berry et al., 2002) and that coccolithophores can maintain Ci fluxes into calcite at rates similar to that of photosynthetic carbon uptake (Buitenhuis et al., 1999; Paasche, 2001). The necessary efflux of ions to balance Ci uptake could readily be met by the Cl− inward rectifier.

Cl− efflux via the inward rectifier may also act to balance efflux of cations during the operation of active transport that is likely to occur to generate a coupling gradient for high-affinity nutrient acquisition. Information on the primary chemiosmotic pumps in the plasma membrane of halotolerant algae and unicellular marine phytoplankton is unfortunately very limited. The utilization of H+-ATPases to generate electrochemical gradients is unlikely in marine algae at seawater pH of 8.0. Several studies have suggested that marine algae use a Na+-based economy at the plasma membrane (Shono et al., 1996; Hildebrand et al., 1997; Popova et al., 1998; Gimmler, 2000). Moreover, a Na+-ATPase has been cloned from Heterosigma akashiwo (Shono et al., 2001). It is now essential to address the question of primary transport mechanisms in calcifying unicellular algae to fully understand how these marine algal cells integrate plasma membrane ion transport during calcification, nutrient acquisition, cell signaling, and cellular ionic homeostasis.

An outward-rectifying current is likely to regulate the C. pelagicus membrane potential in response to events that cause depolarization. Unlike the C. pelagicus Cl− current, the outward cation current exhibits voltage activation and kinetic characteristics that are similar to those of higher plants (White, 1997). Because nonselectivity is a common feature of many plant cation channels (Pineros and Tester, 1997), we are currently investigating the selectivity and regulation of this current to determine whether it can mediate the sustained Ca2+ influx required for intracellular calcification.

Although the occurrence of action potentials and associated currents is widely distributed among algae and higher plants, the excitable property of the C. pelagicus membrane is thus far unique. With the exception of the Chlamydomonas sp. photoreceptor current, the kinetics of algal and plant action potentials and membrane potential transients studied to date are slow (Harz et al., 1992; Miedema and Prins, 1993; Schonknecht et al., 1998), the time course of the characean action potential being 3 to 5 s. In contrast, the kinetics of the C. pelagicus currents that underlie action potentials are very rapid, with the current response complete within 70 ms. Furthermore, in algae and higher plants, the ECl is usually far more positive than Vm and anion channels underlie electrical depolarization during regenerative action potentials and oscillations. For example, in Chara spp., plasma membrane Ca2+-activated Cl− channels underlie action potentials that are initiated by electrical depolarization or mechanical stimuli (Shimmen, 1997; Thiel et al., 1997; Biskup et al., 1999). A similar mechanism for membrane excitability involving transient increase in Cl− conductance is present in the marine diatom C. wailesii where they are proposed to be involved in buoyancy regulation (Gradmann and Boyd, 2000). The action potential currents in C. pelagicus differ fundamentally in that the inward-depolarizing current underlying this excitability is not carried by Cl−, because activation occurs at voltages positive of ECl and EK implying voltage activation of Ca2+ and/or Na+ channels during the depolarizing phase. The function of the rapid action potential current activated by moderate membrane depolarization in C. pelagicus is not clear, but it likely plays a role in environmental signaling possibly via transient Ca2+ elevation.

In summary, using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique, we have characterized the major Cl− inward rectifier of the calcifying phytoplankton C. pelagicus. To our knowledge, this represents the first successful patch-clamp study of any marine phytoplankton cell providing detailed information on the properties and conductances of the plasma membrane. The results show that, unlike marine diatoms, a novel Cl− inward rectifier tightly regulates the coccolithophore membrane potential, modulates membrane excitability, and may act as an electrical shunt for essential nutrient and Ci transporters. The C. pelagicus plasma membrane also exhibits a nonselective, outward-rectifying cation current that may also act as a Ca2+ influx pathway. A major goal is to understand how these predominant conductances in the membrane are coordinated to regulate Ca2+ and Ci uptake during calcification.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of Cell Culture

Coccolithus pelagicus (PLY 182G) cultures were obtained from the Plymouth Culture Collection and maintained as batch cultures in ASW consisting of 450 mm NaCl, 30 mm MgCl2, 16 mm MgSO4, 8 mm KCl, 10 mm CaCl2, and 2 mm NaHCO3. The ASW was supplemented with 500 μm NaNO3, 32 μm K2HPO4, 1 μm Fe-EDTA, and trace metals (Guillard and Ryther, 1962). Cultures were maintained in 250-mL polycarbonate flasks at 15°C under 150 μmol m−2 s−1 light from cold fluorescent tubes. Cultures typically had a 4- to 6-d lag period when seeding cultures with a starting cell density of 300 to 500 cm−3. The exponential growth phase occurred between d 6 and 24, after which the culture entered a stationary phase. A maximum cell density of approximately 10,000 cells cm−3 was observed. The cell size of decalcified C. pelagicus grown under these conditions ranged from 7 to 20 μm.

Specimens of C. pelagicus were prepared for scanning electron microscopy by filtering cells onto 13-mm polycarbonate filters, drying for 24 h at 40°C, and mounting the dried filter on an aluminum stub. Stubs were gold-coated gold before examination with a microscope (JSM-35C, JEOL, Tokyo).

Decalcification and Protoplast Isolation

Samples of cells (5 cm3) were allowed to settle passively before removing the culture solution to produce a concentrated cell sample in approximately 0.2 cm3. Five cubic centimeters of 25 mm EGTA in Ca2+ free ASW was then added to the cell concentrate, and the cells were mixed gently with a plastic transfer pipette. The cells were allowed to settle for a further 15 min before removing the EGTA-ASW media and adding a further 5 cm3 of fresh EGTA-ASW. After a further 10 min, the cells were mechanically agitated by a series of rapid aspirations and expulsions with a plastic transfer pipette before transferring to a recording chamber with a coverslip base. The chamber was secured onto a cooled microscope stage (Research Instruments, Penrhyn, UK) mounted on an inverted microscope (Axiovert, Zeiss, Welwyn Garden City, UK) and maintained at 15°C. To establish that the cells were undamaged by the isolation procedure, samples of decalcified cells were maintained as above, and recalcification was monitored by inspection on the inverted microscope over 4 d.

Patch-Clamp Recording and Analysis

Patch electrodes were fabricated from GC150F glass capillaries (Clark Electromedical, Pangbourne, UK) using a pipette puller (P-833, Narashige, Tokyo). Unpolished pipettes were filled with 0.22 μm of filtered internal recording solution (Millipore, Watford, UK) consisting of 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm HEPES, and 2 mm EGTA, pH 7.2. K+ and Cs+ salts were added as described in “Results” and figure legends. The osmolarity was brought to between 1,000 and 1,200 mosmol L−1 by adding sorbitol. Pipettes were connected to the head stage of an amplifier (Axopatch 200B, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) mounted on a micromanipulator (Research Instruments, Penrhyn) connected to a PC running PCLAMP acquisition and analysis software (Axon Instruments).

The recording chamber volume was 1.5 cm3, and external solutions were exchanged using gravity-fed input and suction output at a rate of 5 cm3 min−1. Patch pipettes varied in resistance from 3 to 15 MΩ depending on the filling solution. The tips of the electrodes were coated in beeswax to minimize stray capacitance but were not fire-polished. Whole-cell recordings were obtained by using a combination of gentle suction, negative pipette potential, and application of a transient current pulse. The whole-cell recording typically stabilized within 60 s, and a further 3 to 5 min was allowed for the pipette contents to fully equilibrate with the cell before voltage-clamp recordings were made. Corrections were made for liquid junction potentials as described previously (Taylor et al., 1996). Leak subtraction was either achieved on-line using the acquisition software (eight pre-pulses) or offline using the input resistance measured just before a family of voltage-clamp pulses. Cell capacitance was estimated using the compensation circuitry of the amplifier, and steady-state currents were corrected for pipette series resistance offline.

Voltage activation curves were acquired by measuring the peak tail current activated by a series of voltage pulses. The tail currents were normalized to the maximum peak current and plotted against activation voltage before fitting with a Boltzmann function using the CLAMPEX (axon instruments) software as follows:

|

where Imax is the normalized maximum peak tail current (i.e. 1), Vm is the test voltage, and S is the slope of voltage activation given by S = RT/δF where R, T, and F have their usual thermodynamic meaning and δ is the gating charge.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the European Union (grant no. IN104381–2083810 to C.B.), by a Leverhulme Special Research Fellowship (to A.R.T.), and by the Biotechnology and Biological Science Research Council (grant no. 226/P15068 to A.R.T. and C.B.).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.011791.

LITERATURE CITED

- Barbara JG, Stoeckel H, Takeda K. Hyperpolarization-activated inward chloride current in protoplasts from suspension-cultured carrot cells. Protoplasma. 1994;180:136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier-Brygoo H, Vinauger M, Colcombet J, Ephritikhine G, Frachisse JM, Maurel C. Anion channels in higher plants: functional characterization, molecular structure and physiological role. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1465:199–218. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(00)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry L, Taylor AR, Lucken U, Ryan KP, Brownlee C. Calcification and inorganic carbon acquisition in coccolithophores. Funct Plant Biol. 2002;29:289–299. doi: 10.1071/PP01218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biskup B, Gradmann D, Thiel G. Calcium release from InsP(3)-sensitive internal stores initiates action potential in Chara. FEBS Lett. 1999;453:72–76. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00600-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CW, Yoder JA. Coccolithophorid blooms in the global ocean. J Geophys Res Oceans. 1994;99:7467–7482. [Google Scholar]

- Buitenhuis ET, de Baar HJW, Veldhuis MJW. Photosynthesis and calcification by Emiliania huxleyi (Prymnesiophyceae) as a function of inorganic carbon species. J Phycol. 1999;35:949–959. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich P, Hedrich R. Anions permeate and gate GCAC1, a voltage-dependent guard cell anion channel. Plant J. 1998;15:479–487. [Google Scholar]

- Elzenga JTM, VanVolkenburgh E. Kinetics of Ca2+- and ATP-dependent, voltage-controlled anion conductance in the plasma membrane of mesophyll cells of Pisum sativum. Planta. 1997;201:415–423. doi: 10.1007/s004250050084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frachisse JM, Colcombet J, Guern J, Barbier-Brygoo H. Characterization of a nitrate-permeable channel able to mediate sustained anion efflux in hypocotyl cells from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2000;21:361–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frachisse JM, Thomine S, Colcombet J, Guern J, Barbier-Brygoo H. Sulfate is both a substrate and an activator of the voltage-dependent anion channel of Arabidopsis hypocotyl cells. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:253–261. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.1.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimmler H. Primary sodium plasma membrane ATPases in salt-tolerant algae: facts and fictions. J Exp Bot. 2000;51:1171–1178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradmann D, Boyd CM. Electrophysiology of the marine diatom Coscinodiscus wailesii: II. Potassium currents. J Exp Bot. 1999;50:453–459. [Google Scholar]

- Gradmann D, Boyd CM. Three types of membrane excitations in the marine diatom Coscinodiscus wailesii. J Membr Biol. 2000;175:149–160. doi: 10.1007/s002320001063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillard RRL, Ryther JH. Studies on marine planktonic diatoms: 1. Cytlotella nana Hustedt and Detonula confervavae (Cleve) Gran. Can J Bot. 1962;8:229–239. doi: 10.1139/m62-029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harz H, Nonnengasser C, Hegemann P. The photoreceptor current of the green-alga Chlamydomonas. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci. 1992;338:39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich R. Voltage-dependent chloride channels in plant-cells: identification, characterization, and regulation of a guard-cell anion channel. Curr Top Membr. 1994;42:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich R, Marten I, Lohse G, Dietrich P, Winter H, Lohaus G, Heldt HW. Malate-sensitive anion channels enable guard-cells to sense changes in the ambient CO2 concentration. Plant J. 1994;6:741–748. [Google Scholar]

- Heidecker M, Wegner LH, Zimmermann U. A patch-clamp study of ion channels in protoplasts prepared from the marine alga Valonia utricularis. J Membr Biol. 1999;172:235–247. doi: 10.1007/s002329900600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand M, Volcani BE, Gassmann W, Schroeder JI. A gene family of silicon transporters. Nature. 1997;385:688–689. doi: 10.1038/385688b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. In channels of excitable membranes. Ed 3. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch TJ, Stein V, Weinreich F, Zdebik AA. Molecular structure and physiological function of chloride channels. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:503–568. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes E, Crofts A, Sanders D. Control of Cl− efflux in Chara corallina by cytosolic pH, free Ca2+, and phosphorylation indicates a role of plasma membrane anion channels in cytosolic pH regulation. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:173–181. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller BU, Hedrich R, Raschke K. Voltage-dependent anion channels in the plasma-membrane of guard-cells. Nature. 1989;341:450–453. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennish MJ. Practical Handbook of Marine Science. Ed 3. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Miedema H, Prins HBA. Simulation of the light-induced oscillations of the membrane-potential in Potamogeton leaf-cells. J Membr Biol. 1993;133:107–117. doi: 10.1007/BF00233792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paasche E. A review of the coccolithophorid Emiliania huxleyi (Prymnesiophyceae), with particular reference to growth, coccolith formation, and calcification-photosynthesis interactions. Phycologia. 2001;40:503–529. [Google Scholar]

- Pineros M, Tester M. Calcium channels in higher plant cells: selectivity, regulation and pharmacology. J Exp Bot. 1997;48:551–577. doi: 10.1093/jxb/48.Special_Issue.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popova L, Balnokin Y, Dietz KJ, Gimmler H. Na+-ATPase from the plasma membrane of the marine alga Tetraselmis (Platymonas) viridis forms a phosphorylated intermediate. FEBS Lett. 1998;426:161–164. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00314-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riebesell U, Zondervan I, Rost B, Tortell PD, Zeebe RE, Morel FMM. Reduced calcification of marine plankton in response to increased atmospheric CO2. Nature. 2000;407:364–367. doi: 10.1038/35030078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonknecht G, Bauer CS, Simonis W. Light-dependent signal transduction and transient changes in cytosolic Ca2+ in a unicellular green alga. J Exp Bot. 1998;49:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Keller BU. Two types of anion channel currents in guard-cells with distinct voltage regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5025–5029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SchulzLessdorf B, Lohse G, Hedrich R. GCAC1 recognizes the pH gradient across the plasma membrane: A pH-sensitive and ATP-dependent anion channel links guard cell membrane potential to acid and energy metabolism. Plant J. 1996;10:993–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Shimmen T. Studies on mechano-perception in Characeae: effects of external Ca2+ and Cl−. Plant Cell Physiol. 1997;38:691–697. [Google Scholar]

- Shono M, Hara Y, Wada M, Fujii T. A sodium pump in the plasma membrane of the marine alga Heterosigma akashiwo. Plant Cell Physiol. 1996;37:385–388. [Google Scholar]

- Shono M, Wada M, Hara Y, Fujii T. Molecular cloning of Na+-ATPase cDNA from a marine alga, Heterosigma akashiwo. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1511:193–199. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(01)00266-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AR, Manison NFH, Fernandez C, Wood J, Brownlee C. Spatial organization of calcium signaling involved in cell volume control in the Fucus rhizoid. Plant Cell. 1996;8:2015–2031. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.11.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry BR, Tyerman SD, Findlay GP. Ion channels in the plasma-membrane of Amaranthus protoplasts: One cation and one anion channel dominate the conductance. J Membr Biol. 1991;121:223–236. doi: 10.1007/BF01951556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel G, Homann U, Plieth C. Ion channel activity during the action potential in Chara: new insights with new techniques. J Exp Bot. 1997;48:609–622. doi: 10.1093/jxb/48.Special_Issue.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomine S, Guern J, BarbierBrygoo H. Voltage-dependent anion channel of Arabidopsis hypocotyls: nucleotide regulation and pharmacological properties. J Membr Biol. 1997;159:71–82. doi: 10.1007/s002329900270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westbroek P, Dejong EW, Vanderwal P, Borman AH, Devrind JPM, Kok D, Debruijn WC, Parker SB. Mechanism of calcification in the marine alga Emiliania-huxleyi. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B-Biol Sci. 1984;304:435–444. [Google Scholar]

- White PJ. Cation channels in the plasma membrane of rye roots. J Exp Bot. 1997;48:499–514. doi: 10.1093/jxb/48.Special_Issue.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zondervan I, Zeebe RE, Rost B, Riebesell U. Decreasing marine biogenic calcification: a negative feedback on rising atmospheric pCO2. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2001;15:507–516. [Google Scholar]