Abstract

The green alga, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, can photoproduce molecular H2 via ferredoxin and the reversible [Fe]hydrogenase enzyme under anaerobic conditions. Recently, a novel approach for sustained H2 gas photoproduction was discovered in cell cultures subjected to S-deprived conditions (A. Melis, L. Zhang, M. Forestier, M.L. Ghirardi, M. Seibert [2000] Plant Physiol 122: 127–135). The close relationship between S and Fe in the H2-production process is of interest because Fe-S clusters are constituents of both ferredoxin and hydrogenase. In this study, we used Mössbauer spectroscopy to examine both the uptake of Fe by the alga at different CO2 concentrations during growth and the influence of anaerobiosis on the accumulation of Fe. Algal cells grown in media with 57Fe(III) at elevated (3%, v/v) CO2 concentration exhibit elevated levels of Fe and have two comparable pools of the ion: (a) Fe(III) with Mössbauer parameters of quadrupole splitting = 0.65 mm s−1 and isomeric shift = 0.46 mm s−1 and (b) Fe(II) with quadrupole splitting = 3.1 mm s−1 and isomeric shift = 1.36 mm s−1. Disruption of the cells and use of the specific Fe chelator, bathophenanthroline, have demonstrated that the Fe(II) pool is located inside the cell. The amount of Fe(III) in the cells increases with the age of the algal culture, whereas the amount of Fe(II) remains constant on a chlorophyll basis. Growing the algae under atmospheric CO2 (limiting) conditions, compared with 3% (v/v) CO2, resulted in a decrease in the intracellular Fe(II) content by a factor of 3. Incubating C. reinhardtii cells, grown at atmospheric CO2 for 3 h in the dark under anaerobic conditions, not only induced hydrogenase activity but also increased the Fe(II) content in the cells up to the saturation level observed in cells grown aerobically at high CO2. This result is novel and suggests a correlation between the amount of Fe(II) cations stored in the cells, the CO2 concentration, and anaerobiosis. A comparison of Fe-uptake results with a cyanobacterium, yeast, and algae suggests that the intracellular Fe(II) pool in C. reinhardtii may reside in the cell vacuole.

Light energy conversion by algae, higher plants, and cyanobacteria is accompanied by water oxidation on the donor side of photosystem II (PSII) with the resultant evolution of molecular O2. The electrons extracted from water by PSII are transported to ferredoxin and NAPD+ via photosystem I (PSI), where they are normally used to fix CO2. However, after anaerobic incubation in the dark, illumination of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Greenbaum, 1982), Chlorella fusca (Kessler, 1974), Scenedesmus obliquus (Gaffron and Rubin, 1942), and some other species of algae leads to the expression of H2-evolution function. Molecular H2 is produced as a result of ferredoxin-mediated electron transport to an induced, reversible [Fe]hydrogenase (rather than to NAPD+ and the Benson-Calvin Cycle) where the enzyme catalyzes the reduction of protons to H2 gas.

There are several types of hydrogenases that catalyze both the synthesis and uptake of molecular H2. The catalytic center of [Fe]hydrogenases contains several Fe-S clusters (Adams and Stiefel, 1998; Peters et al., 1998; Cammack, 1999). The mechanism of photoinduced H2 production and the molecular structure of hydrogenases have been studied extensively (for a review, see Boichenko et al., 2002). These studies are important not only for elucidating basic bioenergetic mechanisms but also for practical implications in the development of alternative energy sources.

Usually, H2-evolving hydrogenases are very sensitive to O2 and are inactivated at partial pressures below 2% (Ghirardi et al., 1997). Because photoproduction of H2 occurs simultaneously with photosynthetic water oxidation and O2 evolution, hydrogenases undergo rapid inactivation in the light, so that the efficiency of H2 production declines very rapidly. However, the “temporal separation” of photosynthetically produced O2 and H2 was recently demonstrated by Ghirardi et al. (2000) and by Melis et al. (2000), which allows for a significant increase in the amount of H2 gas production by certain microalgae. Cultures of C. reinhardtii, grown to the late-log phase, were placed in S-free medium, which causes inhibition of PSII activity and the rate of photosynthetic O2 evolution occur. At about 24 h after S deprivation, O2 evolution activity fell below the rate of respiration, and hence the cultures became anaerobic. Subsequently, the hydrogenase enzyme was induced, and H2 gas production started several hours later.

Thus, culture conditions exert a significant influence on the functional state of photosynthesizing cells, and they can be used to regulate H2 production. Fe and S are closely interrelated in this process because they form the Fe-S clusters found at the catalytic centers of (a) hydrogenases (Adams and Stiefel, 1998; Peters et al., 1998; Cammack, 1999), (b) the sensory system of proteins responsible for metabolic adaptation to anaerobiosis (Taylor et al., 1999), and (c) electron transport carriers taking part in electron transfer from water to hydrogenase.

The goal of the current work was to examine salient features of Fe uptake by C. reinhardtii cells and changes in the chemical state of the Fe atoms in the cells by Mössbauer spectroscopy during the dark, anaerobic induction process that activates hydrogenase function in S-replete cultures (Happe et al., 1994). There are two basic mechanisms for Fe uptake documented in plant cells, strategies I and II (Guerinot and Yi, 1994). Strategy II plants (grasses) take up Fe as an Fe(III)-phytosiderophore complex. In strategy I plants (presumably those other than grasses), extracellular Fe(III)-chelates are reduced by Fe(III)-chelate reductase to Fe(II), which is subsequently transported into the plant cells either by Fe-specific or nonspecific divalent cation transporters (Guerinot and Yi, 1994). Although relatively little has been known about Fe assimilation in green algae, Eckhardt and Buckhout (1998) recently reported that C. reinhardtii cells take up Fe from the surrounding medium using a strategy I-like mechanism. More specifically, they demonstrated that extracellular Fe(III)-chelates were reduced by a plasma membrane enzyme, Fe(III)-chelate reductase, and then the Fe (presumably as Fe(II)) was transported through the membrane into the cell with transport being the rate-limiting step. However, Eckhardt and Buckhout did not determine the redox state of the Fe once it entered the cells, nor could they exclude the possibility that Fe(III) was also transported into the cells. Reduction of externally located ferric ions has been observed in a number of different plants (near root cell surfaces) and in the intestinal tract of animal cells (for reviews, see Guerinot and Yi, 1994; Semin and Ivanov, 1999). However, free ferrous ions are potentially dangerous to cells due to the possible participation of the ion in generating active O2 species (Chevion, 1988). This is why ferrous Fe cations are rapidly oxidized back to the Fe(III) form and normally stored in the ferric form within animal and plant cells.

We found that the algae, grown on medium with ferric Fe, contain two comparable cellular pools of Fe, Fe(II) and Fe(III). The accumulation of Fe(II) inside the cells is a rather unusual observation because ferric Fe is normally accumulated in plant and animal cells that have been examined thus far (Guerinot and Yi, 1994; Semin and Ivanov, 1999). Although we found no evidence for a Fe(II) pool in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus, we do observe it in yeast. Another significant observation from the current work is that the ferrous pool does not reach a saturation level in algae grown at atmospheric levels of CO2, but it does reach saturation when the cells are grown at elevated (3%, v/v) CO2. Adaptation of C. reinhardtii cells to anaerobic conditions after growth at atmospheric CO2 levels stimulates the synthesis of the hydrogenase enzyme and is accompanied by an increase in the Fe(II) pool size from an unsaturated to a saturated level. Mechanisms to explain these phenomena are explored.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

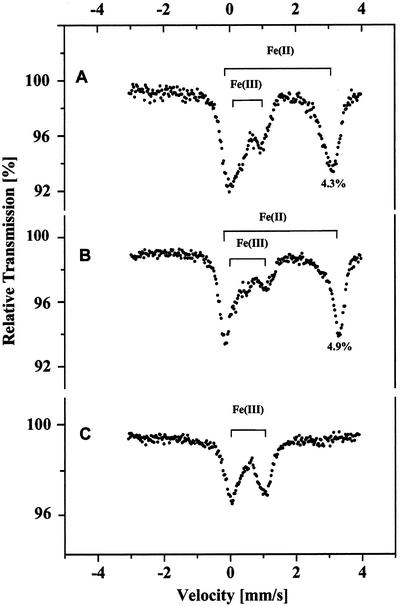

The Mössbauer spectrum of a sample of the C. reinhardtii cells grown under 3% (v/v) CO2 is shown in Figure 1A. The main features of this spectrum are two doublets with quadrupole splitting (Δ) and isomeric shift (δ) factors typical of ferrous and ferric Fe. From the Δ and δ values given in Table I, the ferrous Fe (high-spin) in the C. reinhardtii cells is coordinated mainly with oxygen ligands (e.g. similar to the hexaqua Fe(II) ion, which is characterized by values of Δ = 3.34 mm s−1 and δ = 1.38 mm s−1 [Hendrich and Debrunner, 1989]). The Δ and δ values of the ferric ions are typical of those in Fe-S clusters (Petrouleas et al., 1989), in Fe(III) cations nonspecifically bound to membrane surfaces (Semin et al., 1995), and/or Fe(III) in various Fe storage compounds (i.e. ferritin or hemosiderin; Yang et al., 1987); however, the spin states were not determined for ferric Fe. The presence of high concentrations of ferrous Fe, as stated in the introduction, is unusual in cells. In fact, no spectral evidence for ferrous Fe was observed in S. elongatus cells (Fig. 1C). Moreover, neither a PSI-minus strain of the cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 (Novakova et al., 2001), nor purple photosynthetic bacteria (Aleksandrov et al., 1978) exhibit spectral features typical of ferrous Fe.

Figure 1.

Mössbauer spectra of C. reinhardtii (A and B) and Synechococcus elongatus (C) cells grown in culture medium enriched with 57Fe and bubbled with 3% (v/v) CO2. The cells were collected after 5 d of growth. The effect of 5 mm EDTA on the Fe Mössbauer spectra in the C. reinhardtii cells is shown before (A) or after (B) treatment. Chl contents were 17 and 7.6 mg in the C. reinhardtii and S. elongatus samples, respectively.

Table I.

Mössbauer spectral parameters in C. reinhardtii and S. elongatus cells

| Sample | Doublet No. | Δ | δa | Relative Proportion of Fe Speciesb | Valency of Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm s−1 | % | ||||

| C. reinhardtii | I | 3.1 | 1.36 | 68 | II |

| II | 0.65 | 0.46 | 32 | III | |

| S. elongatus | I | 0.9 | 0.34 | 100 | III |

δ values are measured relative to 57Fe metal.

The Fe contents of the two doublet components are represented as the percentage of the total Fe content in the sample.

In C. reinhardtii cultures, the ferrous Fe signal can be attributed to either the presence of a ferrous Fe salt in the culture medium or to the reduction of Fe(III) by the cells. The 57Fe-containing salt used in the medium was prepared by dissolving Fe metal in concentrated HCl, which forms Fe(II) (Table II, row 1). Further stabilization of the dissolved Fe(II) with citrate (Table II, row 2) and subsequent sterilization of the chelated Fe complex before addition to the culture medium (Table II, row 3) is accompanied by the complete oxidation of Fe(II). The oxidation is thought to be mediated by the chelator, because this process is accompanied by a significant decrease in the redox potential of Fe (Semin et al., 1985) and is stimulated by the sterilization process. Thus, as shown in Table II, all Fe(II) is oxidized during preparation of the algal culture medium.

Table II.

Changes in 57Fe(II) content during preparation of the culture medium

| Solution of Fe | pH | Total Concentration of Fea | Relative Content

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe(II) | Fe(III) | |||

| % | ||||

| Fe/HCl/H2Ob | 1.6 | 13.4 mm | 82 | 18 |

| Fe-citrate Nac | 6.5 | 12.7 mm | 50 | 50 |

| Fe in the growth mediumd | 6.7 | 30 μm | 0 | 100 |

The concentration of Fe(II) was determined spectrophotometrically with o-phenanthroline (λ = 512 nm).

b57Fe metal was dissolved in HCl (4 mg 0.2 mL−1), the solution was diluted with water, and the pH was adjusted to 1.6 by adding NaOH.

Sodium citrate was added to the solution of Fe/HCl/H2O, and the pH of the solution was adjusted to 6.5 (the final concentration of sodium citrate was 106 mm) by adding NaOH.

The Fe-citrate buffer was sterilized at 2 atm for 30 min (precipitation was not observed), and the sterilized solution was added to the culture medium (the final concentration of sodium citrate was 1.5 mm).

Because the culture medium contains no Fe(II), the appearance of this species in preparations of C. reinhardtii cells must be due to the reduction of Fe(III) by the cells. To determine the location of the pool of Fe(II) (i.e. extracellular versus intracellular), we washed the cells with Fe-free medium and observed that the process did not remove ferrous Fe cations (data not shown). Therefore, Fe(II) is either strongly bound to the cell surface or located within the cells. Treatment of the cells with medium containing 5 mm EDTA removes part of the Fe(III) pool, indicating that part of this pool is located on the external surface of cells, but the presence of EDTA in the washing medium had virtually no effect on the Fe(II) content (Fig. 1, compare A and B). Thus, the Fe(II) pool seems to be located inside of the cells because strong binding of Fe(II) cations to surface groups on plant membranes has not been reported (Semin et al., 1995).

To confirm this contention, we washed the algal cells with a medium containing the Fe-specific chelator, bathophenanthroline disulfonic acid disodium salt (BPDS). The cells contain a total of about 0.9 μmol Fe mg−1 chlorophyll (Chl; estimated by measuring the difference in the amount of Fe in the growth medium at the beginning and the end of the growth period), which from Figure 1A is about one-half in the Fe(II) form. Table III shows that washing the cells with 1 mm BPDS releases only 2.4 nmol Fe(II) mg−1 Chl into the medium. This clearly demonstrates that the vast majority of the Fe(II) is not available for extraction from the surface of the cells by the strong Fe(II) chelator, and thus the ferrous-Fe pool must be located inside the cells. Additional strong evidence for this conclusion can also be seen in Table III where partial disruption of the cells by a freeze/thaw procedure results in a sharp (5×) increase of the Fe(II) content in the suspending medium. Hence, we conclude that the ferrous Fe pool is located inside the C. reinhardtii cells and that the cells accumulate Fe largely in the reduced form.

Table III.

Content of Fe(II) in the medium after washing C. reinhardtii cells with BPDS

| Content of Fe in the Medium after Washinga

| |

|---|---|

| Intact Cells | Partially Disrupted Cellsb |

| nmol mg−1 Chl | |

| 2.4 ± 0.4 | 11.1 ± 1.6 |

C. reinhardtii cells contain about 0.9 μm of Fe mg−1 Chl. Intact or disrupted cell were suspended in 10 mm HEPES, 10 mm MgCl2, pH 7.4, containing 1 mm BPDS. They were then pelleted by centrifugation, and the A535 of the supernatant was measured.

Cell pellets were frozen in liquid nitrogen and after 1 h were thawed at room temperature. This caused partial disruption of the cells as confirmed by microscopy.

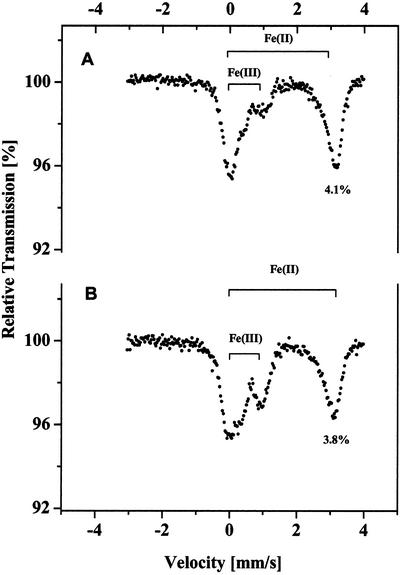

The size of the Fe(II) pool did not change (data not shown) upon (a) incubation of the cells for 3 h in the dark under aerobic conditions (i.e. bubbling with air); (b) exposure of the cells to saturating light intensity or low temperature (8°C); or (c) inhibition of cell respiration with sodium azide. Another feature of the intracellular ferrous Fe pool is that its size (on a Chl basis) remains unchanged during cell growth (Fig. 2). Algal cells collected after different periods of growth in 3% (v/v) CO2 contained virtually equal amounts of Fe(II) but significantly different amounts of Fe(III) (Fig. 2, compare A and B). This fact, together with data presented above, suggests that the size of the intracellular ferrous Fe pool in C. reinhardtii cells, grown under elevated CO2 conditions, is saturated early and thereafter does not depend on the age of the culture.

Figure 2.

Changes in the size of the ferrous and ferric Fe pools in C. reinhardtii cells at different stages of growth in 3% (v/v) CO2. Cells were collected 3 d after inoculation (A) or 7 d after inoculation (B). Chl contents of the samples were 17 and 18 mg, respectively.

Because C. reinhardtii cells take up Fe from the surrounding medium, using the strategy I mechanism (Eckhardt and Buckhout, 1998), reductase-catalyzed reduction of Fe should participate in the formation of the intracellular ferrous Fe pool observed in our experiments. However, because the ferrous pool is localized inside the cell, the role of the ferric reductase in its formation could be either direct or indirect. Ferric Fe reduced by Fe(III)-chelate reductase, as discussed previously, is transported through the plasma membrane (Eckhardt and Buckhout 1998), after which it could be either (a) transported directly to a storage site without oxidation (direct participation) or (b) re-oxidized to Fe(III) inside cell and then re-reduced during transfer from the cytosol to the storage site (indirect participation). Re-oxidation of Fe inside cells is known to occur in yeast (Askwith and Kaplan 1998), and it must also occur in a cyanobacterium as seen below.

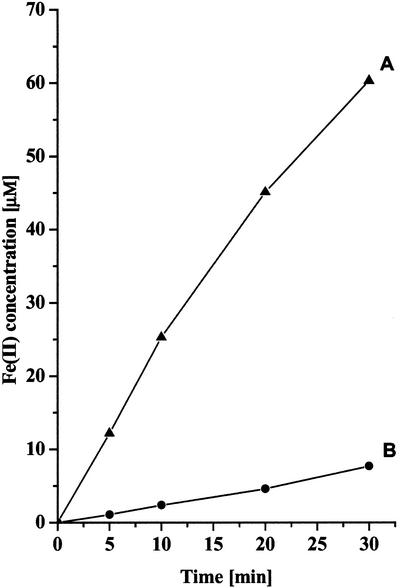

In Figure 1C, we found that the cyanobacterium S. elongatus does not store ferrous Fe inside the cell. However, it is clear from Figure 3 that S. elongatus reduces exogenous Fe(III)-chelate complex and that the reductase activity increases significantly in cells grown under Fe-deficient conditions. This 10-fold increase is a characteristic property of Fe(III)-chelate reductase and of a strategy I mechanism for Fe assimilation (Eckhardt and Buckhout, 1998; Sasaki et al., 1998). Apparently in the cyanobacterium, any Fe(II) that is transported into the cells is immediately re-oxidized to the Fe(III) form (Fig. 1C).

Figure 3.

Reduction of Fe(III)-EDTA complex by Fe-deficient (A) and Fe-sufficient (B) cells. S. elongatus cells were grown for 3 d in Kratz-Myers medium with 15 μm Fe(III)-EDTA or without Fe. After 3 d, the cells were collected by centrifugation, and the Fe(III)-chelate reductase activity was measured (see “Material and Methods”).

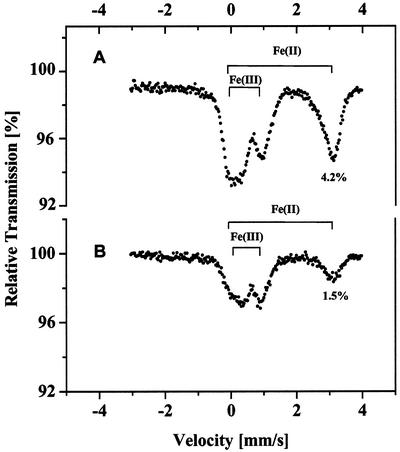

From the results in Figure 1 and Tables I to III, the process of Fe(III) reduction in C. reinhardtii by Fe(III)-chelate reductase should participate in the formation of the Fe(II) pool inside cell. It is known that Fe(III)-chelate reductase is activated by increasing the concentration of CO2 during cell growth (Sasaki et al., 1998). Therefore, we studied the effect of CO2 concentration on the formation of the intracellular ferrous Fe pool by growing C. reinhardtii cells in the presence of two different levels of CO2. Mössbauer spectra of cells grown under either 3% or 0.03% (v/v, atmospheric) CO2 are shown in Figure 4, A and B, respectively. The Fe(II) content of cells grown at 3% (v/v) CO2 is almost three times (4.2% versus 1.5%) that of cells grown under atmospheric CO2 levels. Although the size of the Fe(II) pool increases with the activation of the Fe(III)-chelate reductase due to the presence of elevated levels of CO2 (Fig. 4), this fact alone cannot be used as conclusive evidence for the direct (as distinguished from the indirect) involvement of ferric reductase in the formation of the ferrous pool inside the cell due to possible nonspecific effects of CO2 on the metabolic processes of the cell. What we can conclude, though, is that the Fe(III)-chelate reductase is involved in forming the Fe(II) that is transport into C. reinhardtii cells, but more work will have to be done to determine definitively the exact intracellular storage mechanism.

Figure 4.

Effect of CO2 concentration during C. reinhardtii growth on the size of the intracellular ferrous Fe pool. Cells were grown for 8 d while being bubbled with air supplemented with 3% (v/v) CO2 (A) or for 9 d with non-supplemented air (0.03% [v/v] CO2; B). Chl contents in the samples were 19 and 15 mg, respectively.

The large amount of ferrous component in the C. reinhardtii Mössbauer spectra indicates that significant amounts of Fe are stored in the ferrous form. It is unlikely that ferrous cations in this pool are associated with the normal Fe-containing enzymes in the cells (i.e. the intrinsic Fe-S proteins on the reducing side of PSI, cytochromes, ferredoxin, etc.) because the Fe content of such enzymes in cells is too low to be detected by Mössbauer spectroscopy without preliminary purification of the proteins. Furthermore, the participation of Fe(II) in normal Fe storage structures is also doubtful because only ferric ions are known to bind during the formation of such structures (ferritins and siderophores).

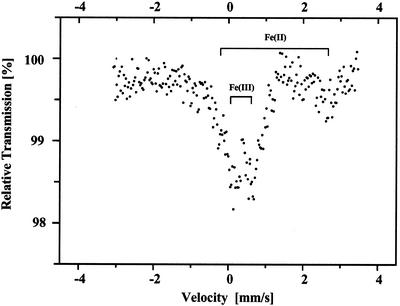

How and where is the Fe(II) stored then? It turns out that yeast, a unicellular eukaryotic microorganism, has vacuoles like C. reinhardtii and stores Fe in its vacuoles (Bode et al., 1995; Li et al., 2001), although the redox state of the stored Fe is not known. We suggest that vacuoles are likely structures in C. reinhardtii for storage of the Fe(II) pool. Several observations support this suggestion: (a) The Mössbauer parameters of the ferrous component correspond to hexaqua Fe(II) ion, which would favor location in the vacuole over the cytoplasm, (b) the Fe(II) pool has a rather low saturation level that can be limited by the volume of the vacuoles, (c) the Fe(II) pool can be stabilized by the acidity of the internal solution in the vacuole (Navon et al., 1979; Boller and Wiemken, 1986) because Fe(II) is stable in acid solution (Kragten, 1978), and (d) cyanobacteria as well as purple bacteria (Gromov, 1985) don't have vacuoles and don't accumulate Fe(II). If our suggestion that C. reinhardtii cells store Fe(II) in their vacuoles is correct, then the Fe that yeast cells store in their vacuoles (Bode et al., 1995; Li et al., 2001) should also be in reduced form. In Figure 5, we found that yeast, like Chlamydomonas cells, store Fe in the reduced form. However, the relative maximum 57Fe absorption of yeast was less (1.5%) than that of C. reinhardtii (5%–6%). The smaller amount of 57Fe observed in yeast cells can be explained by the fact that yeast also stores some Fe(III) (Askwith and Kaplan 1998) and by the difference in composition of growth medium. The C. reinhardtii medium contained 57Fe as the sole source of Fe, whereas the yeast medium contained 56Fe in the yeast autolysate in addition to added 57Fe.

Figure 5.

Mössbauer spectrum of yeast grown in medium containing 57Fe(III)-citrate complex as a source of Fe.

Irrespective of exactly where the Fe(II) is stored, C. reinhardtii cells produce an active reversible hydrogenase during a dark, anaerobic induction period. The activity of the enzyme can be assayed by measuring the initial rates of H2 photoproduction, and the activity reaches a maximum level after about 3 h of anaerobic incubation (Table IV). Cultures grown at 3% (v/v) CO2 exhibited almost three times the anaerobic H2 production rates as those grown at atmospheric levels, perhaps due to increased amounts of storage materials retained by the cells under the former conditions. It is known that stored starch can contribute to H2 production (Ghirardi et al., 2000). The anaerobic induction process in C. reinhardtii was also accompanied by a significant decrease in the redox potential of the culture medium (Table V). This decrease was not observed in anaerobic buffer alone or in S. elongatus cells that do not contain a reversible hydrogenase. Moreover, turning on the light to initiate H2-photoproduction in the cells resulted in a further, fairly rapid additional decrease in the culture redox potential.

Table IV.

Rate of hydrogen photoproduction by the alga, C. reinhardtii, as a function of the growth and induction conditions

| Cell Induction Conditions before Measurement of the Rate of H2 Production | Cell Growth Conditions

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 0.03% CO2 | 3% CO2 | |

| Aerobic | ||

| Without preliminary incubation | 0a | 0 |

| After 20 min incubation in dark | 0 | 0 |

| Anaerobicb | ||

| 1 h incubation in dark | 10.1 | 19.1 |

| 2 h incubation in dark | 13.2 | 30.1 |

| 3 h incubation in dark | 15.4 | 43.3 |

Initial rates of H2 photoproduction in μmol mg−1 Chl h−1.

Anaerobic conditions were generated as described in “Materials and Methods.”

Table V.

Changes of culture redox potential during cell growth in C. reinhardtii and S. elongatus cells and after exposure to anaerobic conditions

| Sample | Content of Cells in the Medium | Aerobic or Anaerobica Conditions | Redox Potential of the Medium (Millivolts vs Normal Hydrogen Electrode) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| °C | ||||

| Water | – | Aerobic | 410 | 19 |

| Aerobic | 395 | 55 | ||

| Bufferb | – | Aerobic | 400 | 19 |

| Anaerobic | 375 | 19 | ||

| C. reinhardtii | ||||

| Cell culture at the beginning of growth (2nd d) | Trace | Aerobic | 380 | 25 |

| Cell culture at the end of growth (9th d) | 21.5 μg Chl mL−1 | Aerobic | 380 | 25 |

| Concentrated cells | 2.1 mg Chl mL−1 | Aerobic | 380 | 25 |

| Anaerobic | 190 | 25 | ||

| Anaerobic and 5 min under saturated light | 70 | 25 | ||

| S. elongatus | ||||

| Cell culture at the beginning of growth (2nd d) | Trace | Aerobic | 405 | 55 |

| Cell culture at the end of growth (5th d) | 43 μg Chl mL−1 | Anaerobic | 380 | 55 |

| Concentrated cells | 2.2 mg Chl mL−1 | Aerobic | 375 | 55 |

| Anaerobic | 290 | 55 |

Anaerobic conditions were created as in Table IV, except that the cells were incubated for 3 h in the dark.

10 mm HEPES, 10 mm MgCl2, pH 7.4.

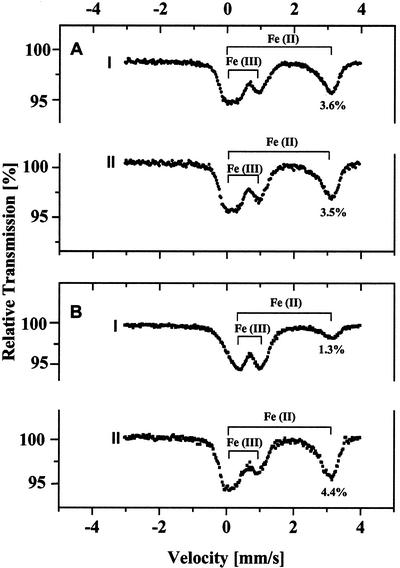

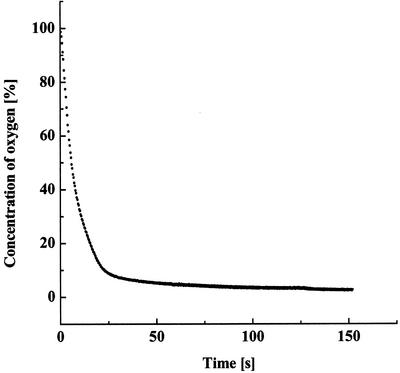

The effect of anaerobiosis on the intracellular Fe concentration depends strongly on the saturation level of the pool of ferrous Fe in the algae. At elevated CO2 concentration (3%), where the Fe(II) pool is already saturated, anaerobiosis has relatively little effect on the amount of ferrous and ferric Fe (Fig. 6A). However, cells grown at atmospheric CO2 levels contain an unsaturated pool of Fe(II) and show a pronounced (3- to 4-fold) increase in the amount of ferrous Fe when exposed to anaerobic conditions (Fig. 6B). In fact, the ferrous Fe pool under anaerobic conditions reached a saturation level of about 4.4%, similar to the level seen in algae grown at 3% (v/v) CO2 (compare Fig. 6B, II, with Fig. 1A). Furthermore, this increase in ferrous Fe content in the low CO2-grown cells is accompanied by a corresponding decrease in the content of ferric Fe. Given the fact that the algal cells were anaerobically induced in Fe-free medium and taking into account the decrease in the ferric Fe Mössbauer spectral features, we suggest that anaerobically induced cells increase the size of their Fe(II) pool by reducing a fraction of the ferric Fe pool. Thus, in addition to the effects of CO2 concentration itself, the results of this study show that, when grown at low CO2 concentrations, the size of the intracellular Fe(II)-pool also depends on the anaerobic state of the cell culture. It is important to note that the observed Mössbauer spectral changes were not due simply to the lack of O2, because anaerobic conditions were reached very rapidly (within a few minutes) during the preparation of a control sample (Fig. 7). The rapid production of anaerobic conditions is the result of respiration in the concentrated cell suspensions before the induction of the hydrogenase enzyme, which in Table IV takes up to 3 h.

Figure 6.

Changes in the size of the ferrous Fe pool in C. reinhardtii cells during adaptation to anaerobic conditions. A, Algal cells containing a saturated pool of ferrous Fe as the result of growth at 3% (v/v) CO2. B, Algal cells containing an unsaturated pool of ferrous Fe as a result of growth in culture medium containing atmospheric levels of CO2. I, Cells not incubated under anaerobic conditions. II, Cells after a 3-h incubation under anaerobic conditions. The O2 was removed as described in “Materials and Methods.” Chl content in all samples was 15 mg.

Figure 7.

Kinetics of O2 uptake by C. reinhardtii cells. The volume of the experimental amperometric cell was 1 mL, and the Chl content in samples was 1 mg mL−1. The cells were grown in 3% (v/v) CO2 and then incubated in the dark.

In summary, the assimilation of Fe in C. reinhardtii is catalyzed by Fe(III)-chelate reductase, and this process proceeds according to the known strategy I mechanism in this organism (Eckhardt and Buckhout, 1998). The mechanism involves the transport of reduced Fe through the cell membrane followed by incorporation of required Fe into Fe-containing proteins (cytochromes, ferredoxin, etc.) and storage of the remaining amount of Fe(II) inside cell. The results of our experiments show that C. reinhardtii cells contain a large, stable, intracellular pool of Fe(II), and the pool size is not saturated in cells grown aerobically at atmospheric CO2 levels. The large amount of ferrous pool emphasizes its probable role as a reserve Fe capacity, and we suggest that it is located in the algal vacuole as is seen in yeast. In our study, we found that this pool increases when the cells are grown aerobically at elevated CO2 concentration. However, the role of Fe(III)-chelate reductase, be it direct or indirect, in the formation of the stable ferrous pool inside the cell is still unclear. Cell adaptation to anaerobiosis is accompanied by both induction of the hydrogenase (Table IV), and when the CO2 concentration is low, by an increase in the size of the intracellular Fe(II) pool (Fig. 6). These findings are of considerable interest in the context of a possible correlation between hydrogenase induction activity under anaerobic conditions and the Fe(III)-chelate reductase activity required for the sequestration of required Fe(II).

Although the ferrous pool may play a role as a cellular Fe storage reservoir, the following additional functions cannot be excluded: (a) a regulatory role in the cells, including, but not limited to, the control of the redox potential in the intracellular medium, required for controlling gene expression during the process of cell adaptation to anaerobic or aerobic conditions (Bauer et al., 1999) or (b) a role as an additional pool of reducing equivalents involved in electron transport reactions in response to alterations of physiological conditions. Finally, increased CO2 content of the atmosphere will have a potentially beneficial effect on algal H2 production (see Table IV) from a future practical perspective, but not due to an increase in Fe(III)-chelate reductase activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Growth

Cells of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (strain 137C mt+) were grown at 25°C under cool-white fluorescence light at 10,000 lux (120 μE m−2 s−1 photosynthetically active radiation) as before (Ghirardi et al., 1997). Cultures in Sager-Granick's medium (Harris, 1989) were bubbled with either air or air supplemented with 3% (v/v) CO2. Synechococcus elongatus (thermophilic strain no. 120 from the collection of the Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology, Moscow) cells were grown in Kratz-Myers medium (Kratz and Myers, 1955) at 55°C under the following light intensity regime: The light was increased from 12 to 18 μE m−2 s−1 over the first 2 d of growth and then raised to 120 μE m−2 s−1 thereafter. The incubation medium was bubbled with air containing 3% (v/v) CO2 unless otherwise indicated.

Yeast (wild-type Saccharomyces cerevisiae, C1–9 strain, was kindly provided by Dr. I.P. Arman, Institute of Molecular Genetics, Moscow) cells were grown in the dark at 32°C with shaking in nutrient medium containing yeast autolysate in addition to inorganic components (Fraikin et al., 1996).

Mössbauer Spectroscopy

Algal, cyanobacteria, and yeast cells were grown in medium containing 57Fe isotope instead of natural Fe. An 57Fe metal powder was dissolved in a small volume of concentrated HCl, and the pH of the resulting solution was adjusted to 1.6. Subsequently, sodium citrate was added to stabilize the Fe, and the pH of the solution was raised to 6.7 (or 5.7 in the case of yeast) by adding NaOH. The resulting stable complex, 57Fe-citrate, was added to the C. reinhardtii growth medium. The final concentrations of 57Fe(II) and citrate in the algal and yeast cell cultures were 30 μm and 1.5 mm, respectively. In the case of the cyanobacterium S. elongatus, 57Fe was stabilized with EDTA as follows. The 57Fe metal powder was dissolved in concentrated HCl, the pH of the solution was adjusted to 1.7, and 335 μm EDTA was added. The resulting Fe-EDTA complex was added to the Kratz-Myers medium. The final concentrations of 57Fe and EDTA in the culture medium were 15 μm and 0.13 mm, respectively. C. reinhardtii and S. elongatus cells were pelleted by centrifugation (4,500g for 5 min) and placed in 0.6-mL sample cuvettes. Seven-hour log-phase yeast cells were washed twice (1,500g for 5 min), and the pellet was transferred to a cuvette after removal of residual moisture with filter paper.

Experimental samples contained 15 to 20 mg of Chl (C. reinhardtii), 7.6 mg of Chl (S. elongatus), or 0.5 × 106 cells (S. cerevisiae), and they were kept under liquid nitrogen until use. Mössbauer spectra were obtained at 80 k in transmission geometry with a 50 mCi of 57Co (Rh) source, and the numbers in the figures are percent transmission (area data are not reported). δs were measured relative to 57Fe metal. Mössbauer spectra were simulated using the standard UVIVEM computer program (MOSTEK, Rostov-na-Donu, Russian Federation).

Measurement of Fe(II) Concentration

Concentrations of Fe(II) in extracellular solutions were determined by measuring the optical density (λ = 512 nm for o-phenanthroline or 535 nm for BPDS) of the colored complex formed by Fe(II) with 1 mm o-phenanthroline (Krishna Murti et al., 1970) or 1 mm BPDS (Eckhardt and Buckhout 1998). Calibration curves, developed using known amounts of Fe(II), were used as a standard.

Ferric Reductase Assay

Cells from growing cultures of S. elongatus were pelleted as above and resuspended in Kratz-Myers medium. The cells were then grown for 3 d in the presence or absence of 15 μm Fe(III)-EDTA, pelleted, and resuspended in Kratz-Myers medium without Fe at a cell concentration equivalent to 0.3 mg Chl mL−1. The cultures were next incubated at 55°C under room light in the presence of 200 μm Fe(III)-EDTA and 600 μm BPDS. After the time intervals indicated in Figure 3, the cells were pelleted, and the absorbance of the supernatant at 535 nm was measured. Concentrations of reduced Fe were calculated using an ε535 of 22,140 m−1 cm−1.

Measurement of O2 and H2 Evolution Rates

The rates of photoinduced O2 and H2 evolution by the algal cells were measured amperometrically in a thermostatically controlled cell (25°C) using a Clark electrode and an LP-7e polarograph (Laboratorni Pristroje, Prague). Concentrations of O2 and H2 were measured in the electrode repolarization mode at a cathode potential of −0.6 and +0.6 V, respectively. The following repolarization electrode conditioning regime was used to regenerate the hydrogen electrodes: +0.6 V for 5 min, −0.6 V for 10 min, +0.6 V for 5 min, −0.6 V for 10 min, +0.6 V for 5 min, and finally −0.6 V for 10 min. The rates of photoinduced O2 and H2 evolution by the thermophilic cyanobacterial cells were measured at 55°C.

Measurements of Redox Potentials

The redox potential of the medium versus normal hydrogen electrode was measured with a platinum electrode and a Ag/AgCl reference electrode (Microelectrodes, Inc., Bedford, NH) using an Accumet pH-meter (Denver Instruments Company, Denver).

Anaerobic Conditions

Anaerobic conditions were achieved by the following procedure. Glc oxidase (1.84 IU mL−1), catalase (5,614 IU mL−1), and Glc (10 mm final concentration; Sigma, St. Louis) were added (Glc oxidase first and then a solution of catalase in Glc) to cell suspensions at 1 to 2 mg Chl mL−1 previously bubbled with argon for 20 min. Subsequently, the suspensions were bubbled again with argon for another 20 min. Samples for H2 measurements were diluted, and samples for Mössbauer spectroscopy were further concentrated. The maximum activity of hydrogenase (measured as the maximum initial rate of molecular H2 photoproduction) was observed after 3 h of cell induction in Fe-free medium under anaerobic conditions in the dark.

Chl Concentration

Chl a + b concentrations in the samples were measured in 80% (v/v) acetone by the method of Arnon (1949).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. E.P. Lukashov for his assistance in the measurement of redox potentials, Dr. M.G. Strakhovskaya for help with the yeast experiments, and Dr. M.L. Ghirardi for her critical reading of this manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (to A.B.R.) and by the Division of Energy Biosciences, Office of Science, U.S. Department of Energy (to M.S.).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.102.018200.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adams MWW, Stiefel EI. Biological hydrogen production: not so elementary. Science. 1998;282:1842–1843. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandrov AY, Novakova AA, Uspenskaya NY, Kiryushkin AA, Kuzmin RN, Rubin AB, Kononenko AA. Mössbauer effect study of intracellular iron in photosynthesizing purple sulfur bacteria. Mol Biol (Russia) 1978;12:55–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnon D. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplast: polyphenol oxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949;24:1–5. doi: 10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askwith C, Kaplan J. Iron and copper transport in yeast and its relevance to human disease. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:135–138. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer CE, Elsen S, Bird TH. Mechanisms for redox control of gene expression. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1999;53:495–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode HP, Dumschat M, Garotti S, Fuhrmann GF. Iron sequestration by the yeast vacuole: a study with vacuolar mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur J Biochem. 1995;228:337–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boichenko VA, Greenbaum E, Seibert M. Hydrogen production by photosynthetic microorganisms. In: Archer MD, Barber J, editors. Photoconversion of Solar Energy: Molecular to Global Photosynthesis. Vol. 2. London: Imperial College Press; 2003. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Boller T, Wiemken A. Dynamic of vacuolar compartmentation. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1986;37:137–134. [Google Scholar]

- Cammack R. Bioinorganic chemistry: hydrogenase sophistication. Nature. 1999;397:214–215. doi: 10.1038/16601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevion M. A site-directed mechanism for free radical induced biological damage: the essential role of redox-active transition-metals. Free Radic Biol Med. 1988;5:27–37. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(88)90059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt U, Buckhout TJ. Iron assimilation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii involves ferric reduction and is similar to strategy I higher plants. J Exp Bot. 1998;49:1219–1226. [Google Scholar]

- Fraikin GY, Strakhovskaya MG, Rubin AB. The role of membrane-bound porphyrin-type compound as endogenous sensitizer in photodynamic damage to yeast plasma membranes. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 1996;34:129–135. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(96)07287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffron H, Rubin J. Fermentative and photochemical production of hydrogen in algae. J Gen Physiol. 1942;26:219–240. doi: 10.1085/jgp.26.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghirardi ML, Togasaki RK, Seibert M. Oxygen sensitivity of algal H2-production. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 1997;63:141–151. doi: 10.1007/BF02920420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghirardi ML, Zhang L, Lee JW, Flynn T, Seibert M, Greenbaum E, Melis A. Microalgae: a green source of renewable H2. Trends Biotechnol. 2000;18:506–511. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(00)01511-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum E. Photosynthetic hydrogen and oxygen production: kinetic studies. Science. 1982;196:879–880. doi: 10.1126/science.215.4530.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromov BV (1985) Structure of Bacteria: Manual. Leningrad University, Leningrad (in Russian)

- Guerinot ML, Yi Y. Iron: nutritious, noxious, and not readily available. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:815–820. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.3.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happe T, Mosler B, Naber JD. Induction, localization and metal content of hydrogenase in the green algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eur J Biochem. 1994;222:769–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris EH. The Chlamydomonas Sourcebook. New York: Academic Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrich MP, Debrunner PG. Integer-spin electron-paramagnetic resonance of iron proteins. Biophys J. 1989;56:489–506. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82696-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler E. Hydrogenase, photoreduction and anaerobic growth of algae. In: Stewart WDP, editor. Algal Physiology and Biochemistry. Oxford: Blackwell; 1974. pp. 456–473. [Google Scholar]

- Kragten J. M Masson, Translation ed, Atlas of Metal-Ligand Equilibria in Aqueous Solution. New York: Ellis Horwood; 1978. p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Kratz WA, Myers J. Nutrition and growth of several blue-green alga. Am J Bot. 1955;42:282–287. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna Murti GSR, Moharir AV, Sarma VAK. Spectrophotometric determination of iron with orthophenanthroline. Microchem J. 1970;15:585–589. [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Chen OS, McVey Ward D, Kaplan J. CCC1 is a transporter that mediates vacuolar iron storage in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29515–29519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103944200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis A, Zhang L, Forestier M, Ghirardi ML, Seibert M. Sustained photobiological hydrogen gas production upon reversible inactivation of oxygen evolution in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:127–135. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.1.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navon G, Shulman RG, Yamane T, Eccleshall TR, Lam K-B, Baronofsky JJ, Marmur J. Phosphorus-31 nuclear magnetic resonance studies of wild-type and glycolytic pathway mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 1979;18:4487–4499. doi: 10.1021/bi00588a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novakova AA, Davletshina LN, Elanskaya IV, Aleksandrov AY, Kiseleva TY, Semin BK, Ivanov II, Vermaas WFJ, Rubin AB. Mössbauer spectroscopy of cyanobacteria Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 devoid of photosystem I and containing inactive phycobilisomes. Biophysics (Russia) 2001;46:482–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JW, Lanzilotta WN, Lemon BJ, Seefeldt LC. X-ray crystal structure of the Fe-only hydrogenase (CpI) from Clostridium pasterurianum to 1.8 angstrom resolution. Science. 1998;282:1853–1858. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrouleas V, Brand JJ, Parrett KG, Golbeck JH. A Mössbauer analysis of the low-potential iron-sulfur center in photosystem I: spectroscopic evidence that FX is a [4Fe-4S] cluster. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8980–8983. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Kurano N, Miyachi S. Induction of ferric reductase activity and of iron uptake capacity in Chlorococcum littorale cells under extremely high-CO2 and iron-deficient conditions. Plant Cell Physiol. 1998;39:405–410. [Google Scholar]

- Semin BK, Aleksandrov AY, Ivanov II, Novakova AA, Parak F, Rubin AB. Investigation of interaction 57Fe3+ with Ca2+-binding site of photosynthetic oxygen-evolving complex of PSII. Biol Membr (Russia) 1995;12:341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Semin BK, Haritonashvili EV, Ivanov II. Study of the interaction of Fe(II) with pyrophosphate and ADP. Stud Biophys. 1985;109:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Semin BK, Ivanov II. Iron deficiency and iron-determined anemia. Med Altera (Russia) 1999;January–March:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BL, Zhulin IB, Johnson MS. Aerotaxis and other energy-sensing behavior in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1999;53:103–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CY, Meagher A, Huynh BH, Sayers DE, Theil EC. Iron(III) clusters bound to horse spleen apoferritin: an X-ray absorption and Mössbauer spectroscopy study that shows that iron nuclei can form on the protein. Biochemistry. 1987;26:497–503. doi: 10.1021/bi00376a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]