Abstract

In plants, metabolic pathways leading to methionine (Met) and threonine diverge at the level of their common substrate, O-phosphohomoserine (OPHS). To investigate the regulation of this branch point, we engineered transgenic potato (Solanum tuberosum) plants affected in cystathionine γ-synthase (CgS), the enzyme utilizing OPHS for the Met pathway. Plants overexpressing potato CgS exhibited either: (a) high transgene RNA levels and 2.7-fold elevated CgS activities but unchanged soluble Met levels, or (b) decreased transcript amounts and enzyme activities (down to 7% of wild-type levels). In leaf tissues, these cosuppression lines revealed a significant reduction of soluble Met and an accumulation of OPHS. Plants expressing CgS antisense constructs exhibited reductions in enzyme activity to as low as 19% of wild type. The metabolite contents of these lines were similar to those of the CgS cosuppression lines. Surprisingly, neither increased nor decreased CgS activity led to visible phenotypic alterations or significant changes in protein-bound Met levels in transgenic potato plants, indicating that metabolic flux to Met synthesis was not greatly affected. Furthermore, in vitro feeding experiments revealed that potato CgS is not subject to feedback regulation by Met, as reported for Arabidopsis. In conclusion, our results demonstrate that potato CgS catalyzes a near-equilibrium reaction and, more importantly, does not display features of a pathway-regulating enzyme. These results are inconsistent with the current hypothesis that CgS exerts major Met metabolic flux control in higher plants.

The sulfur-containing amino acid Met, a crucial metabolite in plant cells, is required not only as a protein component, but also as a precursor for polyamine, ethylene, and biotin biosynthesis (Ravanel et al., 1998) and for secondary metabolites such as S-adenosyl-Met (SAM), the major one-carbon donor in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes (for review, see Tabor and Tabor, 1984). Another Met derivative, S-methyl-Met (SMM), is believed to play an important role in sulfur transport (Bourgis et al., 1999) and the control of intracellular SAM levels in plants (Ranocha et al., 2001; Fig. 1). Three enzymatic steps are involved in de novo Met biosynthesis (for review, see Matthews, 1999). The first enzyme, cystathionine γ-synthase (CgS; EC 4.2.99.9), catalyzes the formation of the thioether l-cystathionine by γ-replacement of the phosphate group of O-phosphohomoserine (OPHS) for the nucleophilic sulfhydryl group provided by Cys (Thompson et al., 1982; Ravanel et al., 1995, 1998). Cystathionine is subsequently converted to homocysteine and finally to Met. Biochemical studies have provided evidence that the first two enzymes involved in Met biosynthesis are located in the chloroplasts (Wallsgrove et al., 1983), whereas the third occurs exclusively in the cytosol (Eichel et al., 1995; Petersen et al., 1995; Zeh et al., 2002). In potato (Solanum tuberosum), two CgS cDNAs (StCgS1 and StCgS2) encoding putative chloroplastidial isoforms, as judged by deduced amino acid sequences, have been isolated and characterized (Hesse et al., 1999; Riedel et al., 1999). Comparison of the coding regions revealed 92.7% similarity (84.3% identity) at the amino acid level. Even at the nucleotide level, both cDNAs show a high identity (83.9%) with the highest divergence in the 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions.

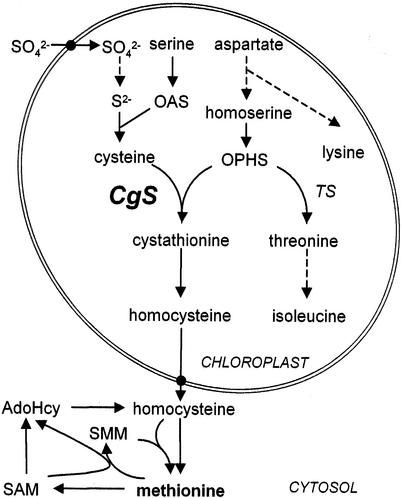

Figure 1.

Biosynthetic pathway of the Asp-derived amino acids in plants. Met synthesis comprises two biosynthetic domains: the reductive sulfur assimilation (leading to Cys biosynthesis) and one branch of the Asp amino acid family biosynthetic pathway. Dashed lines represent parts of the pathway in which detailed descriptions of the enzymatic steps have been omitted. Pathways are shown along with their subcellular compartmentation. CbL, Cystathionine β-lyase; MS, Met synthase; AdoHcy, S-adenosylhomo-Cys.

Considering its importance to various cellular processes, the size of the soluble Met pool is likely to be subject to tight control mechanisms. Although not elucidated in detail yet, two major control elements are of particular interest: Excess amounts of Met (or related metabolites) are known to reduce the stability of CgS mRNA and, thus, decrease concomitant enzyme activity in Lemna paucicostata and Arabidopsis. Feeding studies with Met resulted in decreased CgS activity in L. paucicostata (Thompson et al., 1982; Giovanelli et al., 1985). The characterization of mto1 Arabidopsis mutants, in which CgS modifications result in transcripts resistant to Met-dependent degradation, suggests that CgS is autoregulated at the posttranscriptional level, presumably via a mechanism involving the N-terminal region of the AtCgS protein (Inaba et al., 1994; Chiba et al., 1999; Ominato et al., 2002). Mto1 mutants accumulate high levels of soluble Met (up to 40-fold) in young rosette leaves. Notably, these levels decrease during flowering at the same time levels rise in flowers, thus indicating a spatial and developmental regulation of the size of the soluble Met pool in Arabidopsis. Moreover, studies on CgS-overexpressing Arabidopsis plants revealed that overaccumulation of Met (and SMM) was found to inversely correlate with CgS levels only in tissues of flowering stage plants and not in young plants, suggesting additional and even more important factors contributing to the regulation of the size of the Met pool during plant development (Kim and Leustek, 2000).

As a second major control feature, the efficiency of Met formation is known to be strictly controlled by competition between CgS and Thr synthase (TS) for their common substrate OPHS. The enzymatic activity of plant TS is strongly stimulated by SAM, the end product of the competing pathway (Giovanelli et al., 1984, 1985; Curien et al., 1996). Because Km values of fully activated TS for OPHS have been shown to be 250- to 500-fold lower than those of CgS (Ravanel et al., 1998), carbon flux is directed into the Thr branch when Met and, hence, SAM levels are high. Characterization of transgenic and mutant plants altered in the CgS to TS ratio has provided important evidence for the essential function of this competition for the flow of carbon into either Met or Thr synthesis. Arabidopsis plants expressing CgS antisense mRNA revealed a 4- to 7-fold increase in Thr levels accompanied by severe morphological aberrations due to reduced Met synthesis capacity (Gakière et al., 2000; Kim and Leustek, 2000). More interesting findings were obtained when TS activity was reduced: An Arabidopsis mutant (mto2) deficient in TS enzymatic activity exhibited an accumulation of free Met in young rosette leaves (20-fold), accompanied by comparably reduced soluble Thr contents (down to 6%), but not in mature plants (Bartlem et al., 2000). As a consequence, these results suggest that in young Arabidopsis plants, the regulation of Met synthesis is mainly dependent on the dynamic interplay between changing biochemical properties of CgS and TS (Thompson et al., 1982; Bartlem et al., 2000) and, moreover, when the CgS to TS ratio is altered in favor of CgS, autoregulation of CgS alone is not sufficient to maintain the net rate of Met synthesis.

In contrast to results in Arabidopsis, reducing TS activity in potato plants by using an antisense approach caused a rather disproportional increase of the soluble Met pool (up to 239-fold), as compared with reductions of free Thr levels (up to 55%). Even more interesting, this report also indicated that autogenous regulation of CgS is impaired in potato plants and, hence, might be not conserved among plant species.

In the current article, we aimed to test the assumption that Met production is less dependent on CgS in potato plants than in Arabidopsis. Therefore, we investigated effects of exogenously applied Met on CgS expression and enzymatic activity in different in vitro systems. Moreover, we modulated the ratio of CgS to TS in potato plants by altering the level of CgS transcription using sense and antisense technologies.

RESULTS

Production of Transgenic CgS Sense and Antisense Potato Plants

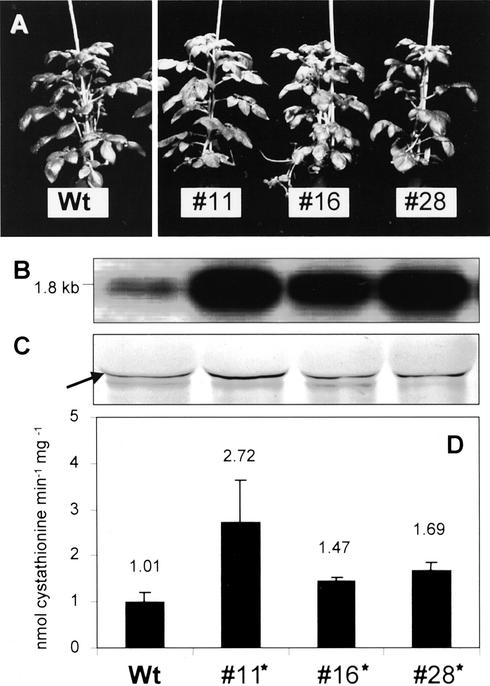

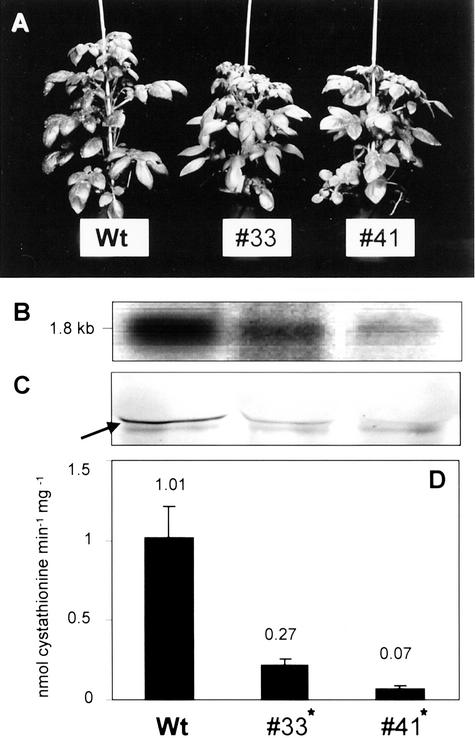

Transgenic potato plants that overexpress CgS were created by placing the potato CgS isoform 1 (StCgS1; Riedel et al., 1999) coding sequence downstream of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter in the plant transformation vector pBinAR (Höfgen and Willmitzer, 1990). Fifty independent kanamycin-resistant transformants were regenerated and used for further analyses based on transcript levels. From the initial transformants, three transgenic lines were selected (sCgS lines 11, 16, and 28) that exhibited increases in CgS mRNA levels (Fig. 2B). Moreover, two lines were identified that revealed cosuppression of CgS (csCgS lines 33 and 41), resulting in a substantial reduction in its transcript levels (Fig. 3B).

Figure 2.

Morphology, RNA-blot analysis, protein-blot analysis, and CgS activity of 8-week-old greenhouse-grown CgS-overexpressing plants compared with potato wild-type plants. A, Morphology of wild-type plants (Wt) and transgenic sCgS lines 11, 16, and 28. In comparison with the controls, no changes in plant growth and development, flowering, or tuber formation were observed during the entire growth period. B, RNA-blot analysis of leaf RNA of transgenic and wild-type plants for the CgS transcript. The size of the sense transcript is 1.8 kb. In comparison with the control, the transgenic lines display substantial CgS transcript accumulation. C, Protein-blot analysis of the CgS. Fifty micrograms of total leaf protein was subjected to CgS detection using a polyclonal antiserum raised against recombinant StCgS. The arrow indicates the position of the StCgS signal (46 kD) as determined in pre-experiments. D, Determination of CgS enzyme activities. OPHS and Cys were used as the physiological substrates for CgS to determine activities in desalted leaf protein extracts (100 μg each). The product formation was demonstrated using HPLC analysis in combination with o-phthaldialdehyde (OPA) derivatization and fluorescence detection. Data are presented as mean values ± sd and result from five individuals per transgenic line, one measurement per plant. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between wild-type and transgenic plants are marked with an asterisk.

Figure 3.

Morphology, RNA-blot analysis, protein-blot analysis, and CgS activity of 8-week-old greenhouse-grown CgS cosuppression plants compared with wild-type plants. A, Morphology of wild-type plants (Wt) and transgenic csCgS lines 33 and 41. In comparison with the controls, no phenotypic alterations concerning plant growth and development, flowering, or tuber formation were observed during the entire growth period. B, RNA-blot analysis of leaf RNA of transgenic and wild-type plants for the CgS transcript. The size of the sense transcript is 1.8 kb, is clearly detectable in both transgenic lines and controls, but demonstrates a clear reduction in both cosuppression lines. C, Protein-blot analysis of the CgS. Fifty micrograms of total leaf protein was subjected to CgS detection using a polyclonal antiserum raised against recombinant StCgS. The arrow indicates the position of the StCgS signal (46 kD) as determined in pre-experiments. D, Determination of CgS enzyme activities. OPHS and Cys were used as substrates for CgS to determine activities in desalted leaf protein extracts (100 μg each). Product formation was demonstrated using HPLC analysis in combination with OPA derivatization and fluorescence detection. Data are presented as mean values ± sd and result from five individuals per transgenic line, one measurement per plant. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between wild-type and transgenic plants are marked with an asterisk.

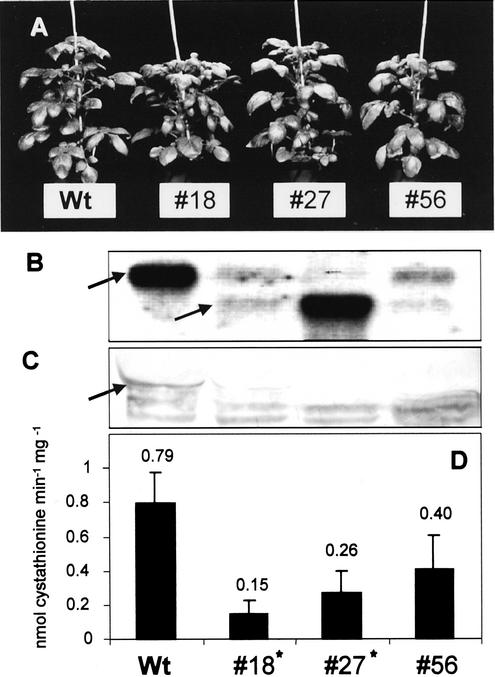

To decrease the activity of the CgS, potato plants were transformed with the vector pBinAR harboring a cDNA encoding a partial sequence of the StCgS1 gene in reverse orientation with respect to the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter. After regenerating 75 independent kanamycin-resistant transgenic plant lines, three lines (aCgS 18, 27, and 56) with reduced steady-state levels of CgS mRNA were selected. Decreased transcript amounts of the endogenous CgS were accompanied by the accumulation of the 600-bp truncated antisense transcript (Fig. 4B). Selected overexpression and antisense plants were amplified and grown in five replicates of each line in the greenhouse to confirm transgene expression and to enable a more detailed analysis of the transformants.

Figure 4.

Morphology, RNA-blot analysis, protein-blot analysis, and CgS activity of 8-week-old greenhouse-grown CgS antisense plants compared with potato wild-type plants. A, Morphology of wild-type plants (Wt) and transgenic aCgS lines 18, 27, and 56. In comparison with the controls, no phenotypic alterations concerning plant growth and development, flowering, or tuber formation were observed during the entire growth period. B, RNA-blot analysis of leaf RNA of transgenic and wild-type plants for the CgS transcript. The size of the sense transcript is 1.8 kb (upper arrow); the antisense transcript has a length of 1.2 kb (lower arrow). Although in wild-type plants only the CgS sense mRNA is present, the transgenic lines 18 and 56, and in particular line 27, show transgene expression of the CgS antisense RNA. The sense messenger is substantially reduced in each antisense line. C, Protein-blot analysis of CgS. Fifty micrograms of total leaf protein was subjected to CgS detection using a polyclonal antiserum raised against recombinant StCgS. The arrow indicates the position of the StCgS signal (46 kD) as determined in pre-experiments. D, Determination of CgS enzyme activities. OPHS and Cys were used as substrates for CgS to determine activities in desalted leaf protein extracts (100 μg each). Product formation was demonstrated using HPLC analysis in combination with OPA derivatization and fluorescence detection. Data are presented as mean values ± sd and result from five individuals per transgenic line, one measurement per plant. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between wild-type and transgenic plants are marked with an asterisk.

Measurements of CgS Protein Content and Enzyme Activity in Transgenic Potato Lines

Immunoblotting of leaf tissue extracts from sCgS plants unexpectedly revealed that an increase in CgS mRNA expression did not lead to identically increased CgS protein accumulation. In comparison with untransformed control plants, sCgS lines exhibited varying CgS levels ranging from only slight increases in lines 16 and 28 to still weak but distinct CgS protein accumulation in line 11 (Fig. 2C). These moderately elevated protein accumulations gave rise to significant 1.4- to 1.7-fold increases in CgS activity in lines 16 and 28. Line 11 revealed a 2.7-fold enhanced catalytic activity (Fig. 2D), thus confirming the findings of the immunoblot analysis.

CgS antisense and cosuppression lines demonstrated a substantial decrease in CgS protein levels in comparison with control plants (Figs. 4C and 3C). As judged by the immunoblot experiments, the level of CgS protein was correlated to the RNA blot, indicating that repression of CgS transcript led to a reduced availability of the corresponding mRNA for translation. Furthermore, these plants exhibited a comparable decrease in total CgS activity. aCgS lines 18, 27, and 56 exhibited approximate reductions to 19%, 33%, and 51% as compared with wild-type activity (Fig. 4D). Cosuppression of CgS had even stronger effects on enzyme activity, yielding a decrease to 7% and 21% in csCgS lines 41 and 33, respectively (Fig. 3D).

Considering these results, we concluded that overexpression and repression of the CgS gene by antisense inhibition or cosuppression resulted in alterations of CgS protein levels, which were in accordance with the corresponding protein quantities and enzyme activities in respective transgenic lines.

Alteration of CgS Activity Does Not Affect Plant Growth and Development in Potato

With the aim to test potential influences of the changes in CgS activity on plant growth and development, potato wild-type plants and the selected transgenic lines were transferred into soil and cultivated under two different greenhouse conditions. Neither increased nor decreased CgS levels led to visible phenotypic differences when compared with control plants under any of the growth conditions (Figs. 2A, 3A, and 4A). Both wild-type and transgenic plants switch from their vegetative to the reproductive stage of development at the same time and show no detectable deviation in size, number, and total yield of the harvested tubers (data not shown).

Effect of CgS Overexpression on Metabolite Levels in Source Leaves, Sink Leaves, and Flowers

The effect of an increased expression of the CgS gene on the amounts of Asp-derived amino acids and thiol compounds was tested. Following the generally believed assumption that the de novo synthesis of amino acids in higher plants occurs in the chloroplasts, source leaf tissues were analyzed for soluble metabolites. Met was also measured in sink leaves and flowers of the transformants because the concentration of soluble Met is presumably temporally and spatially regulated in Arabidopsis after the onset of the reproductive growth and accumulates in sink organs, such as the inflorescence apex (Chiba et al., 1999). However, increases of CgS activity had no substantial impact on the concentrations of soluble end products and intermediates of the Asp pathway in any of the tested potato tissues. As shown in Table I, the amounts of Met revealed no statistically significant alterations in comparison with control plants. Sink leaves of wild-type plants and transgenic sCgS lines 16 and 28 demonstrated an approximately 2-fold increase in soluble Met levels in comparison with source leaves. Though the Met levels observed in sink leaves of sCgS line 11 showed a tendency of increase when compared with those of wild-type plants, there was a high degree of variability among individuals of this plant line. The free Met pool in flowers was increased approximately 5-fold when compared with source leave values, but again no significant differences between wild-type plants and transgenics were measured. Moreover, neither amounts of Cys, one of the CgS substrates, nor levels of Thr changed significantly in the transgenic lines as compared with control plants (Table I). The same holds true for other pathway related metabolites as Asp, Lys, homoserine, Ile, and glutathione, which is derived from Cys (data not shown). The levels of OPHS (second substrate of the CgS), l-cystathionine, homocysteine (both metabolites downstream of the CgS reaction), or SMM (a derivative of Met) were below the detection limit of the analytical methods, even though respective pure substances could be verified in the same order of magnitude as other compounds. These findings were confirmed by analyzing a successive set of plants using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry-based technology according to Roessner et al. (2000, 2001; data not shown).

Table I.

Soluble amino acid contents in source leaves, sink leaves, and flowers of control plants (Wt) and transgenic potato plants overexpressing StCgS1 (sCgS lines)

| Plant | Soluble Amino Acid Content

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Met (source leaf) | Met (sink leaf) | Met (flower) | Thr (source leaf) | Cys (source leaf) | |

| nmol g−1 fresh wt | |||||

| Wt | 2.9 ± 1.0 | 6.5 ± 2.4 | 14.8 ± 2.7 | 94.6 ± 15.6 | 17.4 ± 2.1 |

| No. 11 | 3.0 ± 1.2 | 11.1 ± 5.3 | 18.0 ± 3.6 | 108.6 ± 25.4 | 12.7 ± 2.8 |

| No. 16 | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 8.8 ± 3.9 | 18.9 ± 9.5 | 118.8 ± 14.8 | 16.2 ± 3.3 |

| No. 28 | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 5.8 ± 2.4 | 14.6 ± 2.0 | 93.9 ± 21.0 | 15.1 ± 5.9 |

Metabolites were extracted from leaf tissues of 8-week-old plants or flowers from 10- to 12 week-old plants. Amino acid analysis was performed using reverse phase (RP)-HPLC in combination with either OPA or mono-bromobimane (mBrB) derivatization and fluorescence detection. Amounts of amino acids are given in nanomoles per gram fresh wt and represent mean values ± sd (n = 5).

Effect of CgS Decreases on Metabolite Levels in Source Leaves

Decreases of CgS levels provoked substantial reductions in soluble Met pools, as measured in source leaves of the selected antisense and cosuppression lines. Free Met levels were determined to be reduced to 66%, 52%, and 75%, respectively, when compared with levels observed in wild-type plants (Table II). Moreover, reductions of Met levels were even more pronounced in CgS cosuppression lines. They were calculated to be decreased to 46% and 17% in csCgS lines 33 and 41, respectively.

Table II.

Soluble amino acid contents in source leaves of control plants (Wt), transgenic potato CgS antisense plants (aCgS lines), and cosuppression plants (csCgS lines)

| Plant | Soluble Amino Acid Content

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Met | OPHS | Thr | Cys | |

| nmol g−1 fresh wt | ||||

| Wt | 0.65 ± 0.13 | n.d. | 27.6 ± 13.4 | 16.7 ± 2.4 |

| aCgS no. 18 | 0.44 ± 0.06* | 6.3 ± 4.8 | 28.8 ± 9.9 | 17.6 ± 1.9 |

| aCgS no. 27 | 0.35 ± 0.20* | 4.5 ± 5.9 | 17.3 ± 6.5 | 19.9 ± 2.5 |

| aCgS no. 56 | 0.49 ± 0.11 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 23.9 ± 14.0 | 18.9 ± 3.8 |

| csCgS no. 33 | 0.30 ± 0.08* | 6.5 ± 5.2 | 39.0 ± 15.1 | 15.1 ± 1.9 |

| csCgS no. 41 | 0.11 ± 0.05* | 3.5 ± 1.0 | 23.8 ± 17.9 | 16.3 ± 4.6 |

Metabolites were extracted from leaf tissues of 8-week-old plants and detected using RP-HPLC in combination with either OPA or mBrB derivatization and fluorescence detection. Amounts of amino acids are given in nanomoles per gram fresh wt and represent mean values ± sd (n = 5). Statistically significant changes (P < 0.05) are identified with an asterisk.

Furthermore, repression of CgS caused a considerable accumulation of OPHS, which is the common substrate for Met and Thr biosynthesis in higher plants, though this was accompanied by a considerable variation among the individuals of each line. Because this intermediate was usually not detectable in leaves of wild-type plants, its degree of accumulation could not be determined in a reasonable manner. Yet, concentrations of Cys, the second substrate of the CgS, which provides reduced sulfur for Met synthesis (Hesse and Höfgen, 1998; Saito, 1999), were found to be equal to the control values in all transgenic lines. Moreover, the accumulation of OPHS did not lead to statistically significant increases in soluble Thr levels (Table II). The amino acids Lys, Ile, and Ser also revealed no alterations when compared with the controls (data not shown). These findings were confirmed by analyzing a successive set of plants using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry-based technology according to Roessner et al. (2000, 2001; data not shown).

Manipulation of CgS Does Not Affect the Met Content of Soluble Leaf Proteins

Because reduced soluble Met contents observed in CgS antisense and cosuppression lines might limit its incorporation into proteins, extracts made from source leaves were analyzed with regard to their protein amino acid composition. Protein-bound amino acids were determined by enzymatic hydrolysis of water-soluble proteins followed by HPLC analysis. The proportion of Met found in soluble leaf proteins of transgenic lines repressed in CgS, no matter whether by antisense inhibition or cosuppression, exhibited no significant differences to respective control values. Likewise, contents of protein-bound Met were not significantly altered in CgS overexpression lines (Table III).

Table III.

Met content of leaf proteins of transgenic potato lines altered in CgS enzymatic activity

| Protein-Bound Met Content of StCgS1-Overexpressing Potato Plants (sCgS Lines) in nmol mg−1 total protein | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wt | No. 11 | No. 16 | No. 28 |

| 24.5 ± 5.7 | 20.2 ± 2.9 | 19.8 ± 1.1 | 19.1 ± 0.9 |

| Protein-Bound Met Content of Transgenic CgS Antisense and Cosuppression Plants (aCgS and csCgS, Respectively) in nmol mg−1 total protein | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aCgS | CsCgS | ||||

| Wt | No. 18 | No. 27 | No. 56 | No. 33 | No. 41 |

| 18.3 ± 2.3 | 14.2 ± 4.9 | 15.7 ± 5.3 | 14.3 ± 3.1 | 12.8 ± 3.5 | 13.8 ± 1.7 |

Soluble proteins were extracted from source leaves of 8-week-old control plants (Wt) and StCgS1-overexpressing potato plants (sCgS lines) or from transgenic CgS antisense and cosuppression plants (aCgS and csCgS, respectively),. Each results from independent experiments. After proteolytic cleavage of 200 μg of total protein, Met was determined by RP-HPLC analysis using OPA derivatization and fluorescence detection. Amounts of amino acids are given in nanomoles per milligram of total protein and represent mean values ± sd (n = 3).

In Potato, CgS mRNA Expression and Enzymatic Activity Is Not Subject to Metabolic Control by Met

It was shown for Arabidopsis that increased amounts of soluble Met result in reduced levels of CgS transcript (Inaba et al., 1994; Chiba et al., 1999). These observations gave grounds for the current hypothesis that Met regulates its own synthesis through feedback control of CgS mRNA accumulation (Chiba et al., 1999). In disagreement with this, increased Met content has no detectable effect on CgS mRNA levels, CgS protein accumulation, or CgS enzymatic activities in transgenic TS antisense potato plants (Zeh et al., 2001). To further elucidate the apparent differences between Arabidopsis and potato concerning the regulation of Met synthesis at the step of cystathionine formation, two different in vitro experiments were performed to test the stability of the CgS mRNA in response to Met.

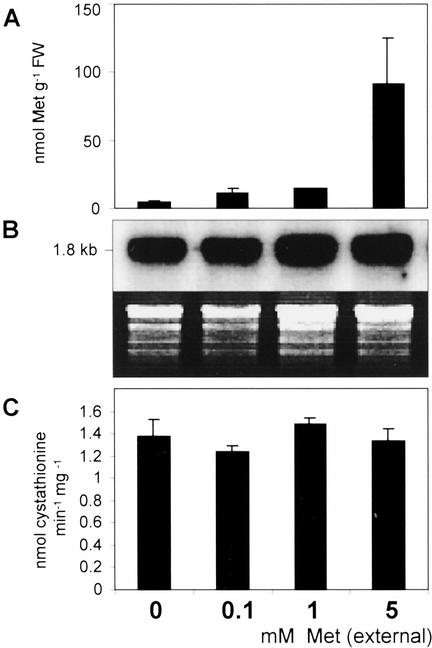

A feeding experiment was carried out using freshly detached compound leaves of potato wild-type plants that were incubated for 24 h under constant light conditions in solutions containing various concentrations of Met. Resulting actual soluble Met pools in the leaves were determined to be 4.4, 11.7, 14.3, and 91.5 nmol g−1 fresh weight (Fig. 5A), referring to external Met concentrations of 0, 0.1, 1, and 5 mm and, hence, demonstrating the suitability of the test system. Compared with controls, elevated Met contents did not lead to changes in steady-state levels of CgS mRNA (Fig. 5B). In agreement with this finding, corresponding CgS enzyme activities were not found to be altered, as indicated by their specific activities of 1.37, 1.23, 1.4, and 1.33 nmol min−1 mg−1 (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Effects of exogenously applied Met on leaf Met content, StCgS expression level, and CgS enzyme activity in detached potato compound leaves of wild-type plants. Compound leaves were freshly cut from 8-week-old greenhouse-grown potato plants and incubated in either 10 mm MES buffer containing 1 mm EDTA or in buffer containing additionally 0.1, 1, or 5 mm Met. Subterminal leaflets of each compound leaf were analyzed after 24 h of incubation under constant light (five samples for each concentration). A, Met uptake was tested by measuring soluble leaf Met contents via RP-HPLC in combination with OPA derivatization and fluorescence detection. B, CgS expression was demonstrated using RNA blot analysis utilizing 10 μg of total RNA and a 32P-labeled EcoRI fragment of the StCgS1 cDNA as a probe. Ethidium bromide-stained rRNA is shown as a loading control. C, CgS enzyme activities were determined in desalted leaf protein extracts (100 μg each) using OPHS and Cys as substrates for CgS. Product formation was determined using RP-HPLC as described above. Actual concentrations of Met and cystathionine were calculated using external standards for calibration.

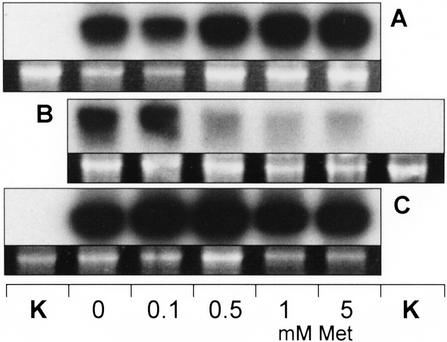

In a second approach, CgS mRNA from potato and Arabidopsis, respectively, were synthesized in vitro in a coupled transcription/translation system based on wheat germ extracts. The intention was to test the transcript stability depending on accurately defined Met concentrations independent from uptake and, further, to facilitate a direct comparison of both species. cDNAs coding for StCgS1 and AtCgS, respectively, were transcribed/translated in presence of 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 5 mm Met. RNA-blot analyses revealed that AtCgS mRNA contents showed a distinct decrease when expressed at Met concentrations higher than 0.1 mm (Fig. 6B), whereas transcript levels of the potato CgS were found to be unaffected by Met within the range of the experimental setup (Fig. 6A). By using the firefly luciferase gene as a positive control, it was clear that gene expression was not generally impaired by Met (Fig. 6C). The result of these experiments suggests that in potato plants CgS is not subject to metabolic control by Met.

Figure 6.

Effects of different concentrations of Met on StCgS mRNA and AtCgS mRNA levels synthesized in a wheat germ in vitro-coupled transcription/translation system. Samples containing 1 μg of linearized plasmid DNA (pBluescript SK−) harboring cDNAs coding for StCgS1 (A) or AtCgS (B), respectively, were incubated in wheat germ extracts containing 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, or 5 mm Met for 90 min at 30°C. RNA-blot analyses were performed utilizing 10 μg of total RNA extracted from the reaction mixtures and either a 32P-labeled 1.2-kb EcoRI fragment of the StCgS1 cDNA or a 1.25-kb SacI fragment of the AtCgS cDNA (Kim and Leustek, 1996) as a probe. Both probes were hybridized with the 3′ sequences of respective CgS transcripts. Wheat germ extract was treated as described above (0.1 mm Met) without DNA template as a negative control (K). Equally synthesized and analyzed mRNA of the firefly luciferase cDNA was used as a positive control (C). Ethidium bromide-stained 25S rRNA is shown as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

Recent results from transgenic Arabidopsis plants manipulated in CgS enzymatic activity levels gave rise to the hypothesis that CgS exerts major flux control for Met metabolism in Arabidopsis (Gakière et al., 2000, 2002; Kim and Leustek, 2000; Kim et al., 2002). This hypothesis is supported by studies indicating that Arabidopsis CgS is feedback-regulated by Met at the posttranscriptional level (Chiba et al., 1999; Bartlem et al., 2000). Using the potato plant as a model system, our aim was to test whether similar mechanisms can be assigned to other plant species.

Until now, molecular investigations of CgS regulation have been focused on a stretch of 39 amino acids, encoded by exon 1 of AtCgS and designated as the MTO1 region, which is believed to act in cis to destabilize its own transcript in a process that involves Met or related metabolites (Chiba et al., 1999). In accordance, AtCgS mRNA levels and enzymatic activities are reduced in the presence of excess Met in Arabidopsis (Inaba et al., 1994; Chiba et al., 1999; Bartlem et a., 2000). In contrast, we could show that increasing the soluble Met pool in potato leaves was not accompanied by changes in levels of CgS transcript or activity. Even more important, quantities of potato CgS (StCgS1) mRNA synthesized in vitro in a transcription/translation system were unaffected by Met even at concentrations higher than might be encountered in a biological system. This is interesting with regard to the fact that Arabidopsis CgS transcript levels markedly decreased when synthesized under similar conditions, thus indicating that mechanisms determining AtCgS transcript accumulation in response to Met are impaired in the potato CgS ortholog. This finding confirms previous results (Zeh et al., 2001).

Although this paradoxical observation is difficult to explain, it cannot be exclusively attributed to the polypeptide encoded by CgS exon 1. The amino acid sequence in the MTO1 region is almost perfectly conserved among plant species, including both potato CgS isoforms, thus indicating a general motif with a functional role (Chiba et al., 1999; Ominato et al., 2002). However, it has to be mentioned that the only known exception is a Val-to-Leu substitution in one of the potato CgS isoforms (StCgS2). Yet, according to Ominato et al. (2002), we do not expect that change to have influence on regulation because it is located near the border of the MTO1 region and does not involve major chemical or sterical alterations in the amino acid chain. Moreover, it can be ruled out that differences in CgS feedback regulation are attributed to species-specific trans-acting factors because mRNA synthesis conditions were identical for both CgS cDNA templates.

Our data suggest that additional levels regulating AtCgS transcript stability involve the nucleotide sequence of the AtCgS exon 1. In contrast to the highly conserved MTO1 amino acid sequences, corresponding nucleotide sequences reveal major differences between Arabidopsis and potato: Homology between AtCgS and the StCgS1 or StCgS2 cDNA is rather low (76.9% or 72.6%, respectively) with respect to the MTO1 coding region. Therefore, we postulate that specific DNA and/or RNA cis-elements contribute to the AtCgS autoregulation. To follow this argument to its logical conclusion, we propose that analogous functional cis-elements are absent in potato plants. Interestingly, Amir et al. (2002) recently reported that the mRNA sequence of the AtCgS exon 1 located near the MTO1 coding region might form stable stem-loop structures as predicted by computer analysis. Thus, the hypothesis that modifications in the nucleotide sequence cause the deregulation of the potato CgS messenger will be crucial to further molecular and biochemical investigations.

To gain further knowledge about the contribution of CgS to the control of Met synthesis in potato plants, we employed different reverse genetic approaches to generate transgenic potato plants displaying increased or decreased CgS enzymatic activity levels. Transgenic potato plants constitutively overexpressing the StCgS1 gene (Riedel et al., 1999) showed no visible phenotype, despite strong increases in CgS transcript and protein accumulation, associated by up to 2.7-fold increases in CgS enzymatic activities. Metabolite analyses demonstrated that soluble Met contents were unchanged in source leaves, sink leaves, and flowers when compared with that of control plants, thus indicating that in vivo achieved increases in CgS activity did not lead to an improved metabolite flux toward Met synthesis. This assumption is strongly supported by the analysis of protein-bound Met levels, which were found to be generally unaltered in leaf tissues of lines overexpressing CgS. Although leaves of sCgS lines revealed moderate increases of soluble Met levels, this was statistically insignificant. Because leaf metabolites are known to display large variations (up to 40%) among equivalent samples (Fiehn et al., 2000; Roessner et al., 2000; 2001; Maimann et al., 2001; Zeh et al., 2001), these changes might simply reflect biological variability and, thus, do not allow further interpretation. The finding that free or bound leaf Met contents are immune to enhanced CgS activity levels was rather unexpected. If potato CgS were to function as a flux-controlling enzyme, even minor increases should enhance the metabolite flux toward Met synthesis and/or its accumulation. Such an effect has been observed in Arabidopsis and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum): Increases in free Met levels (up to 40-fold) and SMM contents (up to 25-fold) were obtained as a result of expressing either full-length or N-terminal truncated AtCgS proteins, respectively (Gakière et al., 2002; Hacham et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2002). As a simple explanation, one might assume that substrates required for cystathionine synthesis are not available in sufficient amounts to cope with increased CgS activity. Yet, this explanation is rather unlikely because precursors of the Met pathway have been proven to be generally not limiting for Met biosynthesis in potato plants (Zeh et al., 2001). The fact that none of the CgS overexpression lines showed significant alterations in soluble Asp, homoserine, or Cys levels corroborates this interpretation. The lack of Met accumulation indicates that potato CgS is present at levels exceeding requirements to provide the overall flux of the pathway and, therefore, is not limiting the rate of Met synthesis in potato plants.

With the intention of inhibiting both known potato CgS isoforms (Hesse et al., 1999; Riedel et al., 1999) in a single transgenic approach, we used a partial sequence of the StCgS1 cDNA showing a high homology of 86.9% to the StCgS2 sequence for antisense expression. Analysis of antisense and cosuppression lines revealed clearly decreased levels of CgS mRNA, protein, and enzymatic activities. Cosuppression of CgS had even stronger effects on activity, resulting in merely 7% residual activity in leaves. Surprisingly, none of these transgenic lines showed visible morphological changes, even during developmental stages with higher demands for Met (for example, the onset of reproductive growth). This is even more impressive with regard to analyses of concomitant free amino acid compositions, revealing that inhibition of CgS was accompanied by substantial and statistically significant decreases in leaf-soluble Met levels. The expectation was that a reduced capacity to synthesize Met would lead to abnormal phenotypes such as severe stunting of growth and an inability to flower, as reported for Arabidopsis CgS antisense plants displaying reductions in CgS activity comparable with those we observed (Gakière et al., 2000; Kim and Leustek, 2000). Though decreased Met levels were consistently observed among potato plants suppressed in CgS, our data also revealed large variations among soluble leaf Met contents between different sets of plants, as indicated by wild-type Met levels shown in Tables I and II. Yet, similar observations have been described by Zeh et al. (2001). This phenomenon might be attributed to slight differences in the developmental stage among analyzed sets of plants or to minor variations in growth conditions in the greenhouse. However, our results still suggest that the bottlenecks resulting from antisense inhibition and cosuppression were effective. Although this interpretation seems to be straight forward because it may also explain the accumulation of the CgS substrate OPHS, it does not account for the observed maintenance of protein-bound Met in CgS antisense and cosuppression lines. The most likely interpretation of this intriguing finding is that decreasing CgS activity does not cause a reduced metabolite flow toward Met synthesis in potato. As a consequence, we have to assume that Met continues to be available for further biochemical processes. At first sight, this striking behavior appears to show, paradoxically, that potato CgS functions primarily to control the metabolic state of the Met pathway and not to control the rate of the corresponding metabolite flux. However, considering that perturbations of enzyme activities bare the risk of introducing artificial control points into a metabolic system (Kacser et al., 1995; Fell, 1997), we suggest that potato CgS catalyzes a near equilibrium reaction under wild-type conditions (as already indicated by the analysis of the CgS-overexpressing plants). Given that, CgS has a rather low flux control coefficient for Met in potato plants—a finding that strongly contradicts the generally accepted model developed for Arabidopsis.

Based on the presented work on potato CgS, we deduced an alternative model for the regulation of de novo Met synthesis in higher plants: The crux of this model is that potato CgS is not the flux-determining step of the pathway because it shows no feedback regulation and demonstrates a low flux control coefficient for Met synthesis. The same holds true for the enzymes downstream of the CgS, namely CbL and MS, because they do not increase the flow of metabolites when overexpressed in potato (Maimann et al., 2000; Nikiforova et al., 2002). As the remaining regulatory feature, we propose that the balancing of the fluxes into the Met and Thr branches is almost exclusively executed by TS activity levels in potato, whereas carbon skeletons are distributed mainly due to CgS/TS competition in Arabidopsis. Our finding that changing the CgS to TS ratio by manipulating CgS activity levels does not affect flux toward Met (and Thr) in potato supports this interpretation. Even more evidence is provided by previous studies, in which expression of TS from Escherichia coli leads to 5-fold increased Thr levels and reduced Met contents in transgenic solanaceous plants (Muhitch, 1997). In as much, our hypothesis could explain why suppression of the potato TS gave rise to a much lower molar decrease in leaf Thr contents than increase in soluble Met (Zeh et al., 2001), whereas impaired TS activity caused an accumulation of Met at the expense of nearly equimolar reductions in Thr levels in rosette leaves of young Arabidopsis mto2 mutant plants (Bartlem et al., 2000). Last but not least, sizes of soluble Met and Thr pools in Solanaceae seem to be strongly mediated by the availability of carbon resources. For that reason, enhancing the overall carbon flux toward Met and Thr synthesis by expressing a feedback-insensitive Asp kinase caused up to 9-fold rises in Thr in transgenic tobacco plants (Shaul and Galili, 1992; Galili, 1995). The observation that Met levels remained constant under these conditions might reflect that the common substrate OPHS is preferably channeled toward Thr production in wild-type plants (Thompson et al., 1982).

Yet, how can all these differences in pathway regulation be reconciled? There is no doubt that important regulatory features remain to be uncovered. Nevertheless, our data demonstrate that de novo synthesis of Met in potato is much more flexible than in Arabidopsis and, as a consequence, that potato plants can tolerate large variations in the soluble Met pool. Reasons for this could be attributed to adaptive differences between plant species. Ben-Tzvi Tzchori et al. (1996) pointed out that Asp, which provides the carbon skeleton for Met and Thr, might be more available in Solanaceae than in Arabidopsis. Considering a relatively short timescale from germination to seed formation, Arabidopsis might utilize strict flux control to avoid inefficient consumption of resources. Because potato plants exhibit longer growth periods mainly adjusted to generate tubers as sink organs in their later growth phase, such efficient mechanisms for flux control or regulation of metabolite pools, respectively, may not be necessary. Therefore, our results contribute to the hypothesis that Met metabolic flux control mechanisms are not ubiquitous among all plant species (Miron et al., 2000; Zeh et al., 2001; Amir et al., 2002; Galili and Höfgen, 2002).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of Transgenic Potato Lines

Potato (Solanum tuberosum cv Désirée; Saatzucht Lange AG, Bad Schwartau, Germany) CgS (designated StCgS1; GenBank accession no. AF082891; Riedel et al., 1999) was cut from pBluescript SK− as a truncated 1.2-kb EcoRI fragment and digested with Klenow enzyme from Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I to generate blunt ends. The fragment was ligated in reverse orientation with respect to the 35S promoter into the vector pBinAR-Kan (Höfgen and Willmitzer, 1990) previously cut with SmaI to provide an antisense construct for plant transformation. To create a construct for stable overexpression of CgS, the full-length StCgS1 cDNA (1.8 kb) was cut from pBluescript SK− as a BamHI/Asp718 fragment and cloned into the same sites of the vector pBinAR-Kan. Transformation of potato plants was carried out by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated gene transfer (Rocha-Sosa et al., 1989) using the strain C58C1/pGV2260 (Deblaere et al., 1985) as described by Dietze et al. (1995). Transgenic plants were selected on kanamycin-containing medium (10 mg L−1) supplemented with casein hydrolysate (200 mg L−1). The resulting transgenic lines were transferred into soil and grown in the greenhouse at 20°C with a light/dark rhythm of 16 h/8 h. Transformants were screened for changes in CgS transcript levels by RNA-blot analyses of leaf tissues. Standard techniques were essentially executed as described by Sambrook et al. (1989).

Plant Cultivation

Transgenic CgS-overexpressing and antisense plants were propagated in tissue culture along with potato wild-type plants and transferred into soil after 2 weeks of cultivation. The rooted shoots were planted in small pots and grown in the phytotron with a light regime of 200 to 250 μmol s−1 m−1 (16 h/8 h) under a hood to retain high air humidity. After 2 weeks, plants were transferred into pots with a diameter of 20 cm and cultivated in a greenhouse providing nearly natural light conditions with an approximately 16-h-light/8-h-dark period plus natural sunlight. Light intensity and temperature were dependent on environmental conditions, but light did not fall below 250 to 300 μmol photons m−2 s−1, and temperature did not sink below 18°C. Alternatively, plants were grown in a seasonally (March–September) used “summer greenhouse” providing only natural light and temperature conditions. Leaf material was harvested from greenhouse-grown plants after approximately 8 weeks of cultivation, before the onset of flowering. Leaf discs were excised from tissues of similar developmental stage. Transition to the reproductive stage could usually be observed only in plants older than 10 weeks. In accordance, flowers were collected from 10- to 12-week-old plants. All plant material was sampled between 10 and 12 am and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen before storage at −80°C.

Extraction and Analysis of Soluble Amino Acids

Soluble amino acids were determined following a modified protocol from Scheible et al. (1997). Leaf tissues (about 100 mg per plant) were ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen in a bead mill and extracted three times for 20 min at 80°C: once with 400 μL of 80% (v/v) aqueous ethanol (buffered with 2.5 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5) and 10 μL of 20 μm l-nor-Val (as an internal standard), once with 400 μL of 50% (v/v) aqueous ethanol (buffered as before) and once with 200 μL of 80% (v/v) aqueous ethanol. Between the extraction steps, the samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 rpm, and the supernatants were collected. The combined ethanol/water extracts were stored at −20°C or directly subjected to RP-HPLC using an ODS column (Hypersil C18; 150- × 4.6-mm i.d.; 3 μm; Knauer GmbH, Berlin) connected to an HPLC system (Dionex, Idstein, Germany). Amino acids were measured by precolumn derivatization with OPA in combination with fluorescence detection (Lindroth and Mopper, 1979) as described by Ravanel et al. (1996). Peak areas were integrated by using Chromeleon 6.30 software (Dionex) and subjected to quantification by means of calibration curves made from standard mixtures.

Extraction and Analysis of Soluble Thiol Compounds

Individual soluble thiols were determined as the sum of their reduced and oxidized forms. One hundred milligrams of fresh ground leaf material (see above) was added to 100 mg of polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (previously washed with 0.1 m HCl) and 1 mL of 0.1 m HCl. The samples were shaken for 60 min at room temperature. After centrifugation (15 min at 14,000 rpm; 4°C), the supernatants were frozen at −20°C until reduction/derivatization. Thiols were reduced by incubating 120 μL of the extracts with 200 μL of 0.25 CHES-NaOH (pH 9.4) and 70 μL of freshly prepared 10 mm dithiothreitol for 40 min at RT. According to Fahey et al. (1981), thiols were derivatized for 15 min in the dark after adding 10 μL of 25 mm mBrB to each sample. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 220 μL of 100 mm methanesulfonic acid and incubation for 30 min in the dark. After centrifugation (15 min at 14,000 rpm; 4°C), the supernatants were submitted to RP-HPLC analysis. The separation of thiols was performed according to Blaszczyk et al. (2002) using an ODS column (Eurosphere C18; 200- × 4.6-mm i.d.; 5 μm; Knauer GmbH) and a Dionex HPLC system. Mixed standards treated exactly as the sample supernatants were used as a reference for the quantification of Cys and glutathione content.

Analysis of Protein-Bound Amino Acids

The determination of protein bound amino acids was carried using HPLC analysis after proteolytically cleaving soluble leaf proteins with Pronase (Roche, Manheim, Germany). The suitability of this method was tested by hydrolyzing different quantities of soluble leaf proteins. Released amino acids were linearly correlated to corresponding protein amounts within the tested range (10–400 μg of total proteins). Moreover, the digestion of bovine serum albumin revealed an amino acid composition according to published data (Brown, 1975). Protein concentrations were determined according to Bradford (1976).

About 250 mg of fresh ground leaf material (see above) was extracted in 1 mL of 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mm CaCl2, and 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100. Aliquots of 500 μL were desalted using pre-equilibrated NAP-5 columns (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany). Protein hydrolysis was performed by utilizing extract volumes containing 200 μg of protein and 1 unit of Pronase for each sample in a total volume of 800 μL of 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5) and 10 mm CaCl2. To enable efficient degradation, proteins were digested at 37°C for 2 d. Amino acids were then extracted by adding 400 μL of methanol and 200 μL of chloroform to 500 μL of each reaction mix. After centrifugation (10 min at 14,000 rpm; 4°C), the upper, aqueous phase was subjected to amino acid analysis via HPLC as described above. Concurrently, three samples containing no protein extract were treated in the same manner to quantify the background resulting from Pronase self-digestion.

RNA- and Protein-Blot Analysis

Total potato leaf RNA was prepared according to Logemann et al. (1987). Thirty micrograms of total RNA was loaded per lane on denaturing 1.5% (w/v) agarose gels containing 15% (w/v) formaldehyde. Gels were blotted to nylon membranes, hybridized under stringent conditions with specific radioactively labeled cDNA-probes. To examine mRNA expression of both isoforms of the StCgS, we utilized a 1.2-kb internal EcoRI fragment of the StCgS1 cDNA (Riedel et al., 1999) showing high homology (86.9%) to the corresponding StCgS2 sequence (Hesse et al., 1999). Arabidopsis CgS mRNA contents were analyzed using a 1.25-kb SacI fragment of the AtCgS cDNA (Kim and Leustek, 1996). The level of gene expression was estimated from resulting x-ray films. Protein-blot analyses were performed as described by Maimann et al. (2000) using the polyclonal antibodies described there.

CgS Assay

CgS activity was measured following the protocol provided by Zeh et al. (2001), which is based on the method described by Ravanel et al. (1995). CgS activity measurements were carried out using desalted protein extracts (100 μg total protein) made from source leaf tissues of 8-week-old greenhouse-grown plants utilizing OPHS (ChiroBlock GmbH, Wolfen, Germany) and l-Cys as the physiological substrates of the CgS. Product formation (l-cystathionine) was determined after 30 min of incubation according to the protocol for the HPLC analysis of amino acids.

Feeding Experiments with Detached Potato Compound Leaves

Feeding experiments were carried out using compound leaves directly cut from 8-week-old greenhouse-grown potato plants. To avoid xylem embolism, the compound leaves were cut again under a buffer solution (10 mm MES and 1 mm EDTA [pH 6.5]) and then immediately transferred to fresh buffer containing 0.1, 1, and 5 mm dissolved Met. Detached potato compound leaves were incubated in buffer without Met as a control. After 24 h of incubation under constant light conditions (120 μmol m−2 s−1), leaf discs were taken from subterminal leaflets and analyzed for soluble Met, CgS mRNA levels, and CgS enzyme activities as described above.

Feeding Experiments Using an in Vitro Transcription and Translation System

The full-length AtCgS cDNA was generated from Arabidopsis (Columbia-0) rosette leaf mRNA templates by utilizing the First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Pharmacia). PCR was performed using oligonucleotide primer covering the flanking regions of the AtCgS coding region and proof reading Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany). Sequence analysis of the 1.7-kb PCR product revealed identity with the published AtCgS sequence (CGS1; Kim and Leustek, 1996; GenBank accession no. U43709). The AtCgS cDNA was ligated into the pBlueScript SK− (Stratagene) via BamHI/Asp718 restriction sites introduced by PCR amplification and subjected to further analysis.

In vitro transcription and translation of the full-length cDNA of the StCgS1 or AtCgS, respectively, was performed using the TNT coupled wheat germ system (Promega, Madison, WI). Reaction mixtures were prepared by utilizing an amino acid mixture lacking Met supplied by the manufacturers. Final concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 5 mm Met were adjusted by adding appropriate quantities of this amino acid to each reaction mixture separately. Moreover, respective cDNAs were expressed in the absence of Met. After incubation at 30°C for 90 min, reactions were stopped by freezing the samples in liquid nitrogen. StCgS and AtCgS transcript levels were subsequently determined via RNA-blot analysis as previously described. To ensure that the application of Met was not limiting the transcription rate and/or transcript stability in general, expression analysis of the firefly luciferase gene (provided by the manufacturer) was performed as a positive control.

Statistical Analysis

The Student's t test method (Microsoft Excel 2000, Microsoft, Redmond, WA) was routinely used to determine the significance of differences between means of data sets. Mean values were compared under the assumption that the variances of both ranges of data are unequal; it is referred to as a heteroscedastic t test. Differences between data sets were regarded as significant in case probabilities of error were below 5% (P < 0.05).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Romy Ackermann for performing the potato transformations, the gardeners for excellent greenhouse work, and Josef Bergstein for photographical assistance. We thank Prof. Mark Stitt, his technical assistant Regina Feil, and Dr. Malcolm Hawkesford for their support during metabolite analyses. We would like to thank Dr. Stefanie Maimann and Dr. Michaela Zeh for providing the antibodies for CbL and MS. Moreover, we wish to thank Dr. Bertrand Gakière for fruitful discussions and Megan McKenzie for carefully editing this manuscript. We are grateful to Prof. Lothar Willmitzer for supporting this work.

Footnotes

This work was supported by European FP4 (no. Bio–4CT–97–2182) and FP5 (no. QLRT–2000–00103) project grants and by the Max-Planck-Society.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.102.015933.

LITERATURE CITED

- Amir R, Hacham Y, Galili G. Cystathionine γ-synthase and threonine synthase operate in concert to regulate carbon flow towards methionine in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:153–156. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlem D, Lambein I, Okamoto T, Itaya A, Uda Y, Kijima F, Tamaki Y, Nambara E, Naito S. Mutation in the threonine synthase gene results in an over-accumulation of soluble Met in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:101–110. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Tzvi Tzchori I, Perl A, Galili G. Lysine and threonine metabolisms are subjects to complex patterns of regulation in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;32:727–734. doi: 10.1007/BF00020213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczyk A, Sirko L, Hawkesford MJ, Sirko A. Biochemical analysis of transgenic tobacco lines producing bacterial serine acetyltransferase. Plant Sci. 2002;162:589–597. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgis F, Roje S, Nuccio ML, Fisher DB, Tarczynski MC, Li CJ, Herschbach C, Rennenberg H, Pimenta MJ, Shen TL et al. S-methylmethionine plays a major role in phloem sulfur transport and is synthesized by a novel type of methyltransferase. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1485–1497. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.8.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein using the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JR. Structure of bovine serum albumin. Fed Proc. 1975;34:591–591. [Google Scholar]

- Chiba Y, Ishikawa M, Kijima F, Tyson RH, Kim J, Yamamoto A, Mambara E, Leustek T, Wallsgrove RM, Naito S. Evidence for autoregulation of cystathionine γ-synthase mRNA stability in Arabidopsis. Science. 1999;286:1371–1374. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curien G, Dumas R, Ravanel S, Douce R. Characterization of an Arabidopsis thaliana cDNA encoding an S-adenosylmethionine-sensitive threonine synthase-threonine synthase from higher plants. FEBS Lett. 1996;390:85–90. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00633-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblaere R, Bytebier B, de Greve H, Debroek F, Schell J, van Montagu M, Leemanns J. Efficient octopine Ti plasmid-derived vectors of Agrobacteriummediated gene transfer to plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:4777–4788. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.13.4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietze J, Blau A, Willmitzer L. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of potato (Solanum tuberosum) In: Potrykus I, Spangenberg G, editors. Gene Transfer to Plants XXII. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1995. pp. 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Eichel J, González JC, Hotze M, Matthews RG, Schröder J. Vitamin-B12-independent methionine synthase from higher plant (Catharanthus roseus): molecular characterisation, regulation, heterologous expression, and enzyme properties. Eur J Biochem. 1995;230:1053–1058. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey RC, Newton GL, Dorian R, Kosower E. Analysis of biological thiols: quantitative determination of thiols at the picomole level based upon derivatization with monobromobimanes and separation by cation-exchange chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1981;111:357–365. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90573-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell D. Understanding the control of metabolism. In: Snell K, editor. Frontiers in Metabolism 2: Understanding the Control of Metabolism. London: Portland Press Ltd.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fiehn O, Kopka J, Dörmann P, Altmann T, Trethewey RN, Willmitzer L. Metabolic profiling for plant functional genomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:1157–1161. doi: 10.1038/81137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gakière B, Denis L, Droux M, Job D. Over-expression of cystathionine γ-synthase in Arabidopsis thaliana leads to increased levels of methionine and S-methylmethionine. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2002;40:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Gakière B, Ravanel S, Droux M, Douce R, Job D. Mechanisms to account for maintenance of the soluble methionine pool in transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing antisense cystathionine γ-synthase cDNA. C R Acad Sci III. 2000;323:841–851. doi: 10.1016/s0764-4469(00)01242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili G. Regulation of lysine and threonine synthesis. Plant Cell. 1995;7:899–906. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili G, Höfgen R. Metabolic engineering of amino acids and storage proteins in plants. Metab Eng. 2002;4:3–11. doi: 10.1006/mben.2001.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanelli J, Mudd SH, Datko AH. In vivo regulation of de novo methionine biosynthesis in a higher plant (Lemna) Plant Physiol. 1985;77:450–455. doi: 10.1104/pp.77.2.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanelli J, Veluthambi K, Thompson GA, Mudd SH, Datko AH. Threonine synthase of Lemna paucicostataHegelm. 6746. Plant Physiol. 1984;76:285–292. doi: 10.1104/pp.76.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacham Y, Avraham T, Amir R. The N-terminal region of Arabidopsis cystathionine γ-synthase plays an important role in methionine metabolism. Plant Physiol. 2002;128:454–462. doi: 10.1104/pp.010819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse H, Basner A, Willmitzer L, Höfgen R. Cloning and characterisation of a cDNA (accession no. AF082892) encoding a second cystathionine γ-synthase in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) (PGR 99-161) Plant Physiol. 1999;121:1057. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse H, Höfgen R. Isolation of cDNAs encoding cytosolic (accession no. AF044172) and plastidic (accession no. AF044173) cysteine synthase isoforms from Solanum tuberosum. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:1604. [Google Scholar]

- Höfgen R, Willmitzer L. Biochemical and genetic analysis of different patatin isoforms expressed in various organs of potato (Solanum tuberosum) Plant Sci. 1990;66:221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Inaba K, Fujiwara T, Chino M, Komeda Y, Naito S. Isolation of an Arabidopsis thaliana mutant, mto1, that overaccumulates soluble methionine. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:881–887. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.3.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kacser H, Burns JA, Fell DA. The control of flux. Biochem Soc Trans. 1995;23:341–366. doi: 10.1042/bst0230341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Lee M, Chalam R, Martin MN, Leustek T, Boerjan W. Constitutive overexpression of cystathionine γ-synthase in Arabidopsis leads to accumulation of soluble methionine and S-methylmethionine. Plant Physiol. 2002;128:95–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Leustek T. Cloning and analysis of the gene for cystathionine γ-synthase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;32:1117–1124. doi: 10.1007/BF00041395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Leustek T. Repression of cystathionine γ-synthase in Arabidopsis thalianaproduces partial methionine auxotrophy and developmental abnormalities. Plant Sci. 2000;151:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lindroth P, Mopper K. High performance liquid chromatographic determination of subpicomole amounts of amino acids by precolumn fluorescence derivatization with o-phthaldialdehyde. Anal Chem. 1979;51:1667–1674. [Google Scholar]

- Logemann J, Schell J, Willmitzer L. Improved method for the isolation of RNA from plant tissues. Anal Biochem. 1987;163:16–20. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maimann S, Höfgen R, Hesse H. Enhanced cystathionine β-lyase activity in transgenic potato plants does not force metabolite flow towards methionine. Planta. 2001;214:163–170. doi: 10.1007/s004250100651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maimann S, Wagner C, Kreft O, Zeh M, Willmitzer L, Höfgen R, Hesse H. Transgenic potato plants reveal the indispensable role of cystathionine β-lyase in plant growth and development. Plant J. 2000;23:747–758. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews BF. Lysine, threonine and methionine biosynthesis. In: Singh BK, editor. Plant Amino Acids: Biochemistry and Biotechnology. New York: Dekker; 1999. pp. 205–225. [Google Scholar]

- Miron D, Ben-Yaacov S, Reches D, Schupper A, Galili G. Purification and characterisation of a bifunctional lysine-ketoglutarate reductase/saccharopine dehydrogenase from developing soybean seeds. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:655–663. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.2.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhitch MJ. Effects of expressing E. coli threonine synthase in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) suspension culture cells on free amino acid level, aspartate pathway enzyme activities and uptake of aspartate into cells. Plant Physiol. 1997;150:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforova V, Kempa S, Zeh M, Maimann S, Kreft O, Casazza AP, Riedel K, Tauberger E, Höfgen R, Hesse H. Engineering of cysteine and methionine biosynthesis in potato. Amino Acids. 2002;22:259–278. doi: 10.1007/s007260200013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ominato K, Akita H, Suzuki A, Kijima F, Yoshino T, Yoshino M, Chiba Y, Onouchi H, Naito S. Identification of a short highly conserved amino acid sequence as the functional region required for posttranscriptional autoregulation of the cystathionine γ-synthase gene in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36380–36386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204645200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen M, Van der Straeten D, Bauw G. Full-length cDNA clone from Coleus blumei (accession no. Z49150) with high similarity to cobalamin-independent methionine synthase. Plant Physiol. 1995;109:338. [Google Scholar]

- Ranocha P, McNeil SD, Ziemak MJ, Li C, Tarcynski MC, Hanson AD. The S-methylmethionine cycle in angiosperms: ubiquity, antiquity and activity. Plant J. 2001;25:575–584. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravanel S, Droux M, Douce R. Methionine biosynthesis in higher plants: I. Purification and characterisation of cystathionine γ-synthase from spinach chloroplasts. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;316:572–584. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravanel S, Gakière B, Job D, Douce R. The specific features of methionine biosynthesis and metabolism in plants. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7805–7812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel K, Mangelsdorf C, Streber W, Willmitzer L, Höfgen R, Hesse H. Isolation and characterization of a cDNA encoding cystathionine γ-synthase from potato. Plant Biol. 1999;1:638–644. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha-Sosa M, Sonnewald U, Frommer W, Stratmann M, Schell J, Willmitzer L. Both developmental and metabolic signals activate the promoter of the class I patatin gene. EMBO J. 1989;8:23–29. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03344.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roessner U, Luedemann A, Brust D, Fiehn O, Willmitzer L, Fernie AR. Metabolic profiling allows comprehensive phenotyping of genetically or environmentally modified plant systems. Plant Cell. 2001;13:11–29. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roessner U, Wagner C, Kopka J, Trethewey RN, Willmitzer L. Simultaneous analysis of metabolites in potato tuber by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Plant J. 2000;23:1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K. Biosynthesis of cysteine. In: Singh BK, editor. Plant Amino Acids: Biochemistry and Biotechnology. New York: Dekker; 1999. pp. 267–291. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Ed 2. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Scheible W, Gonzales-Fontes A, Morcuende R, Lauerer M, Geiger M, Glaab J, Gojon A, Schulze E, Stitt M. Tobacco mutants with a decreased number of functional nia genes compensate by modifying the diurnal regulation of transcription, post-translational modification and turnover of nitrate reductase. Planta. 1997;203:304–319. doi: 10.1007/s004250050196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaul O, Galili G. Threonine overproduction in transgenic tobacco plants expressing a mutant desensitized aspartate kinase from Escherichia coli. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:1157–1163. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.3.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabor CW, Tabor H. Methionine adenosyltransferase (S-adenosylmethionine synthetase) and S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase. Adv Enzymol. 1984;56:251–282. doi: 10.1002/9780470123027.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson GA, Datko AH, Mudd SH. Methionine biosynthesis in Lemna: studies on the regulation of cystathionine γ-synthase, O-phosphohomoserine sulfhydrylase, and O-acetyl sulfhydrylase. Plant Physiol. 1982;69:1077–1083. doi: 10.1104/pp.69.5.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallsgrove RM, Lea PJ, Miflin BJ. Intracellular localization of aspartate kinase and the enzymes of threonine and methionine biosynthesis in green leaves. Plant Physiol. 1983;71:780–784. doi: 10.1104/pp.71.4.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeh M, Casazza AP, Kreft O, Roessner U, Bieberich K, Willmitzer L, Höfgen R, Hesse H. Antisense inhibition of threonine synthase leads to high methionine content in transgenic potato plants. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:792–802. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeh M, Leggewie G, Höfgen R, Hesse H. Cloning and characterization of a cDNA encoding a cobalamine-independent methionine synthase from potato (Solanum tuberosumL.) Plant Mol Biol. 2002;48:255–265. doi: 10.1023/a:1013333303554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]