Abstract

Ernst Wynder, founder and President of the American Health Foundation, was my employer, mentor, and colleague for nearly 25 years. This brief rememberance provides some experiences and perspectives that influenced my career as a cancer epidemiologist.

The American Health Foundation (AHF) was a unique institution founded by Ernst Wynder in 1969. It was a crucible for mixing and melding inspirations and ideas from disparate branches of the health sciences in the service of prevention of cancer and other chronic diseases that are the major causes of death and disability in our society. AHF had programs in epidemiology, tobacco and chemical carcinogenesis, nutritional carcinogenesis, and health behavior and promotion. Its extensive laboratories included a Research Animal Facility which could support bioassays with several thousand rodents, pathology and histology labs, an instrumentation facility which provided state of the art capacity for studies requiring GC/MS equipment, statistical consultation, and computing resources.

In 1975 AHF consolidated its basic sciences, clinical research, and a child health center in a new, specially designed building in Valhalla, NY, adjacent to New York Medical College. The facility was formally named The Naylor Dana Institute, in recognition of the Eleanor Naylor Dana Foundation which contributed funds towards its construction, as did the National Cancer Institute and private donors. The physical arrangement accorded with Wynder's idea of an integrated cancer prevention center, a concept which he spent much of his later years refining and pursuing as a policy goal.1 However, Wynder always felt the need to maintain a presence in Manhattan, close to potential donors as well as near the institutions that formed the mainstay of his trademark hospital-based case-control studies: Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York University Medical Center, New York Hospital, and Presbyterian Hospital (the two latter hospitals, affiliated with the Cornell Medical School and Columbia University, respectively, merged in 1998 to become the New York Presbyterian Hospital).

In the present-day era of multidisciplinary research and initiatives such as the NIH Roadmap, it seems almost unthinkable that putting so many different kinds of scientists under the same small roof was once a truly unique and in many ways revolutionary idea. To those of us who worked there the organizational scheme seemed quite natural. When I started at AHF in 1975, I did not realize how extraordinary it was that epidemiologic research should not merely exist side by side with basic sciences but should interact on a daily basis and continuously draw its inspiration from them and vice versa. It simply seemed the natural way to do things.

This unique environment was the conception of Ernst Wynder who believed that disease prevention is the ultimate goal of applied epidemiology and can best flourish alongside the basic sciences. The co-existence and synergy between these two realms was an essential part of Wynder's thinking and a highly visible characteristic of his research programs throughout his entire career. As early as 1953 he realized that the many questions raised by his landmark study of smoking and lung cancer2 could not be answered by epidemiology alone, but required a coordinated approach in which biology and chemistry played major roles. With his Washington University mentor and collaborator Evarts Graham, he embarked on an experimental program to demonstrate the carcinogenicity of particulate matter isolated from cigarette smoke.3,4,5 In the late 1950s, after he had moved to the Sloan-Kettering Institute in New York, he and chemist Dietrich Hoffmann began a highly productive collaboration that lasted four decades and produced 81 publications.6

Years before translational research became a central tenet of NIH programs, Wynder was already putting it into practice in the field of preventive medicine. In 1972, the year in which the journal Preventive Medicine began publication, the Epidemiology Division of AHF moved to new quarters at 1370 Avenue of the Americas alongside a public service facility called the Health Maintenance Institute (HMI). This enterprise was part research laboratory and part wellness center (that term had also not yet been invented, and the sight of gyms on every New York City corner was still decades in the future). HMI was organized into four intervention clinics: smoking cessation, nutrition, hypertension, and physical fitness. Wynder held the strong conviction that since heart disease and other common chronic diseases have multifactorial causes their prevention requires a multifactorial approach. His inspiration was to house all of these activities under one corporate roof using new computer technology to evaluate the needs of individuals rapidly and with prevention resources close at hand.

The enterprise drew much of its scientific support from the already legendary Framingham study as well as the more recent mega-cohort studies of the American Cancer Society such as Cancer Prevention Study I (CPS-I) led by E. Cuyler Hammond and Larry Garfinkel. (I could not foresee when I came to AHF that I would later join Garfinkel to work on the successor study CPS-II.) Wynder cited these studies to justify putting his ideas into practice, but was also realistic about cost. Realizing that it was impractical to expect federal research support for such a venture, he set up the HMI as a separate entity, the American Health Corporation, with support from Control Data Corp. (CDC, then the world's leading builder of supercomputers), Eastman Kodak Co., The Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Co., Norton Simon, Inc., Time Inc., and Bradford Computer & Systems Inc. (later bought by McDonald Douglass)7 The involvement of two cutting-edge computer firms led to an institutional appreciation within AHF for computing and biostatistics. With Wynder's encouragement we experimented with combinations of in-house computing using new minicomputer technology from Data General Corp., plus extramural time-shared access to newly emerging statistical packages such as BMD (not yet re-christened BMDP) and SPSS. In those pre-Internet days remote access was still somewhat of a novelty, yet we managed to adapt to the diverse needs and backgrounds of our staff by maintaining computer accounts at the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences at New York University, Columbia University, and the City University of New York.

Not coincidentally, our multi-purpose workspace served as one of the 28 nationwide recruitment sites for MRFIT – the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial funded and overseen by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. MRFIT (pronounced Mr. Fit) was a randomized primary prevention trial begun in 1973 to test the effect of a multifactor intervention program on mortality from coronary heart disease (CHD) in 12,866 high-risk men aged 35 to 57 years. Men were randomly assigned either to a special intervention program consisting of stepped-care treatment for hypertension, counseling for cigarette smoking, and dietary advice for lowering blood cholesterol levels, or to their usual sources of health care in the community.8 A natural outgrowth of the Framingham study, MRFIT was one of several coronary heart disease prevention trials recommended by the 1970 Task Force on Arteriosclerosis to NHLBI in 1971 as an alternative to a national single-factor dietary trial, which was judged to be infeasible. Although the trial did not achieve the success many had hoped for,9 the multisite coordination effort and parceling out of statistics, quality control, laboratory, and analysis functions proved to be a robust model for design and conduct of yet more complex studies for decades to come, including the Women's Intervention Nutrition Study (WINS) which Wynder eventually led.10

The involvement of AHF in the MRFIT study had two useful side effects. First, it provided an opportunity for Wynder to maintain a close ongoing relationship with Jerome Cornfield, the chief statistical architect of MRFIT. Cornfield was himself a colorful figure in the world of cancer epidemiology. He belonged to an elite group of biostatisticians, including Nathan Mantel, whom Wynder held in highest esteem. Lacking tools for analyzing data in the rapidly evolving field of epidemiology they invented methods that eventually became standard techniques. From his earliest days of tobacco research Wynder sought Cornfield's collaboration and drew heavily on his advice.11,12 Cornfield was assisting us with our study of saccharin and bladder cancer13 up until the time of his death in 1979. His untimely demise from pancreatic cancer affected Wynder deeply, and he never ceased to talk about Cornfield's many contributions to his own research career.

The second MRFIT spin-off was a lasting institutional involvement in hands-on training of the lay public in preparation of healthful meals. In the pre-Lipitor days, the dietary intervention in MRFIT consisted largely of advising trial participants on ways to reduce intake of saturated fats and dietary cholesterol and restriction of caloric intake. Wynder felt that this approach could be greatly improved. In 1978, when the Epidemiology Division moved into the Ford Foundation in what would be its permanent headquarters until Wynder's death more than two decades later, a kitchen was built in a basement suite and was used for recipe experimentation and cooking demonstrations.

Beyond his well known role as a founding father of cancer epidemiology, Wynder had a broad, humanitarian side. I encountered this almost as soon as I joined AHF, at a 1975 symposium he organized at Rockefeller University titled "The Illusion of Immortality;" NBC anchorman and author Edwin Newman moderated. A quarter century had elapsed since Wynder and Sir Richard Doll had independently shaken the medical world with the first studies of smoking and lung cancer, 2,14 yet the first Surgeon-General's report, which quoted extensively from Wynder's studies, was already accumulating dust on the shelf.15 Wynder gathered some of the leading intellectuals of the day to discuss the seeming disconnect between people's knowledge of causes of heart disease and many cancers and their inaction in implementing broad preventive measures. Speakers included anthropologist Ashley Montagu ("The Natural Superiority of Women"), the existential psychologist Rollo May ("Psychology and the Human Dilemma"), and theologian and peace activist William Sloan Coffin – a daring choice in the early post-Vietnam era. Heart surgeon Michael DeBakey sounded the major theme, noting how frequently his recovering patients resumed smoking while ignoring their high blood pressure. Wynder summed up the conference saying "Man tends to live for the moment, believing that tomorrow will take care of itself. He does not like to consider the possibility of crippling illness or death. … A man doesn't take his car for granted. He brings it in for a regular checkup. But he takes his body for granted."

While he frequently sounded the theme of personal responsibility as an important component of prevention of lifestyle-related disease, he understood that effective approaches are often beyond the reach of individuals and believed they must be shouldered by society as a whole. He was very active in the policy arena, speaking and writing extensively about what he called the "managerial" approach to prevention. He was a strong supporter of governmental regulation of machine-measured cigarette yields in the early days when our NCI-funded studies indicated that filter cigarettes were less hazardous than non-filters.16 However, over the next decade or so he gradually changed his views as non-filter cigarettes were displaced from the market and apparent risk differences between different types of cigarettes diminished. Writing in 1988 he noted:

"Although the low-yield cigarette has provided some assistance to smokers, smoking prevention is far more important, and greater efforts are needed to achieve cessation, particularly among women and minority groups. Beyond this approach, efforts to prevent children and young people from beginning to smoke should stress State-mandated school health education beginning in the earliest grades." 17

In his later years he urged public agencies to emulate the AHF experience by creating interdisciplinary centers for tobacco-related cancer research,18 and he stressed the urgent need for institutions and professionals in many disciplines to make a serious commitment to prevention, including

"… various segments of the research community and society as a whole, i.e., Cancer Centers and hospitals, epidemiologists, laboratory scientists, legislators, educators and behavioral scientists, and the media. … For the current policy initiatives in tobacco-related cancer control to succeed, there needs to be a focus on preventing the initiation of tobacco use among children and adolescents. All segments of society can help to achieve this goal. In the nation's research planning, there needs to be a proper balance between basic and applied research, including research on and application of preventive principles." 19

His policy interests extended to diet and nutrition. He was highly cognizant of the limitations of dietary assessment in epidemiological studies20 but also felt that the totality of evidence from experimental, metabolic, and population studies justified specific recommendations regarding "optimal" intake of fats and fibers, which he called the 25/25/diet (25% of calories as fat and 25 g of fiber per day).21 Together with Christine Williams he promulgated a dietary recommendation for children age 2 and older equivalent to their age plus 5 g/day.22

Wynder was acutely aware of the limitations as well as the strengths of epidemiology and was constantly discussing and seeking ways to improve methodology. He frequently expressed his concern that associations in epidemiology, especially studies of diet and nutrition, were rarely as strong as those between smoking and lung cancer. Acting on this concern, in 1986 (nine years before Science magazine reporter Gary Taubes stirred up the field with his article "Epidemiology faces its limits" 23) Wynder, together with Ian Higgins and Leon Gordis (then Chair of Epidemiology at Johns Hopkins and later author of a successful epidemiology text24) organized a workshop at AHF on the Epidemiology of Weak Associations. The workshop, published in Preventive Medicine, included a review of study designs by Johns Hopkins professor Moyses Szklo25 who would later write his own textbook of epidemiology,26 a categorical treatment of bias by Manning Feinleib, then Director of the National Center for Health Statistics,27 one by myself on confounding,28 an article by Reuel Stallones on subgroup analysis,29 and a paper by James Schlesselman on causal judgment.30 Nowadays, of course, these subjects are all core topics in every epidemiology curriculum.

It is important to point out that Wynder's preoccupation with epidemiologic methods and their impact on study interpretation predated the workshop by several decades. Even his landmark paper on smoking and lung cancer showed a keen attentiveness to bias and confounding. In that paper he did what we would now call a sensitivity analysis by using multiple control groups, took pains to probe the validity of questionnaire findings by different interviewers, separated findings according to lung tumor histology, and examined the impact of latency.2 He continued to think and write about the challenge of studying weak associations long after the 1986 workshop.31

Wynder seemed to know about important events in cancer science almost before they happened. The secret of his apparent omniscience was not difficult to learn: he spoke to everyone of importance frequently and nearly round the clock. I would often come into his office and find him on the phone with an NCI official such as Peter Greenwald or the late Guy Newell or a well-informed organizational executive such as Margaret Foti at the American Association for Cancer Research. The only event on which I managed to scoop him was when I was first to learn of the appointment of Paul Kleihues as Director of IARC, and then only because it occurred while I was staying in Lyon with Paolo Boffetta, a senior IARC official.

This constant sounding out of important and influential people had both scientific and political aspects, and I don't pretend to know where one left off and the other began, or even whether there was in his mind a distinct boundary between the two realms. Certainly Wynder's ability to attract both private funding and peer-reviewed NCI support for construction and operation of the Valhalla laboratories attests to strong instincts in both arenas. He had an unfailing sense of where the next likely fundable areas were, and part of the success of the Foundation during his years as President was due to his steering projects towards those areas. Throughout his tenure the Foundation continuously maintained its status as an NCI-designated basic cancer center and was always supported by a Cancer Center Support Grant.

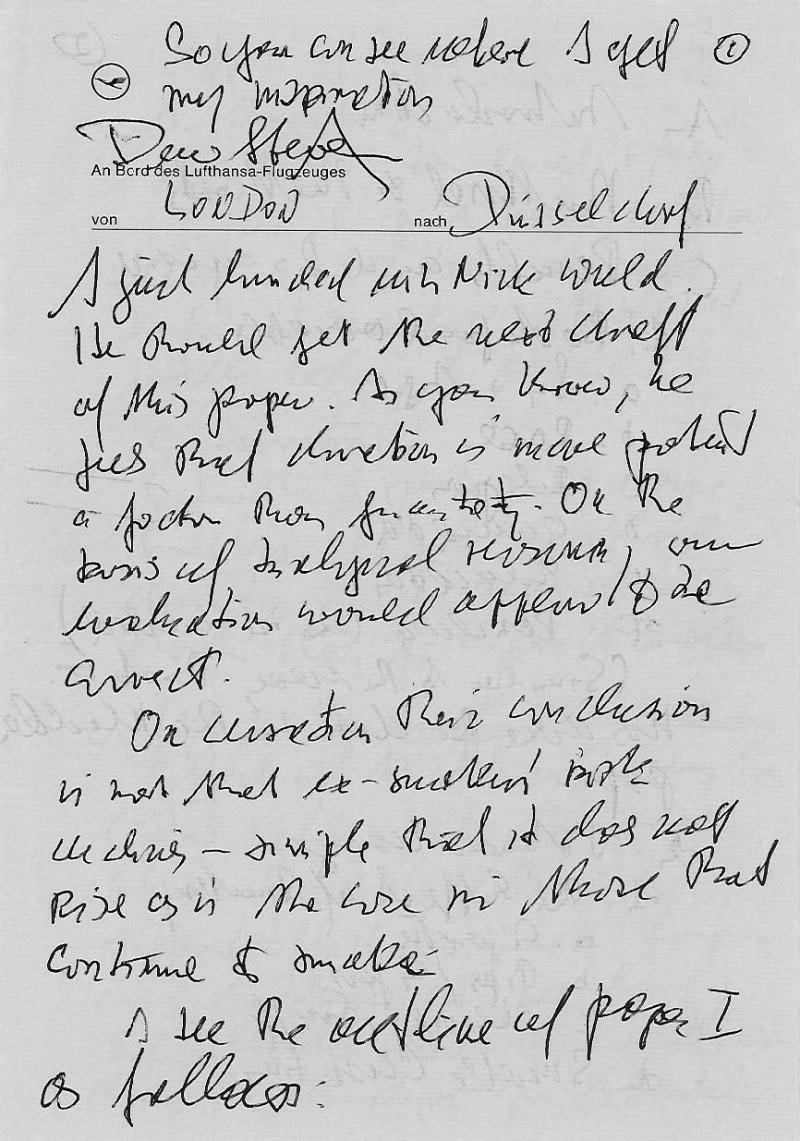

When not on the phone, entertaining visiting scientists, or perusing data Wynder was traveling. He was constantly sought after as a speaker, and his round-the-world trips were legendary. Wynder used transit time to revise and rewrite, sending back hand-written manuscript outlines on in-flight stationery from Pan Am and hotels in exotic places such as the Excelsior Copacabana – Rio de Janeiro. Even in the air his thoughts were often on our research. Figure 1 shows a hand-written note from 1979 written on Lufthansa stationery with the header "An Bord des Lufthansa-Flugzeuges von London nach Düsseldorf" with the inscription "So you can see where I get my inspiration." In that note he goes on to say "I just lunched with Nick Wald [a prominent British researcher in tobacco and health]. He should get the next draft of this paper. As you know he feels that duration is more potent a factor than quantity. On the basis of analytical research, our findings would appear to be correct." This general piece of encouragement was followed by eight closely written pages outlining proposed changes to our current manuscript, and concluding with the request: "I hope you can make these modifications and have the next draft on my desk by July 2. Please give it to Mr. [David] Davies [AHF Executive Vice President] who then can take the paper to my home in Scarborough. I also hope that you can get a draft of paper II prepared at that time." This note also mentions a scheduled conference with Cornfield.

FIGURE 1.

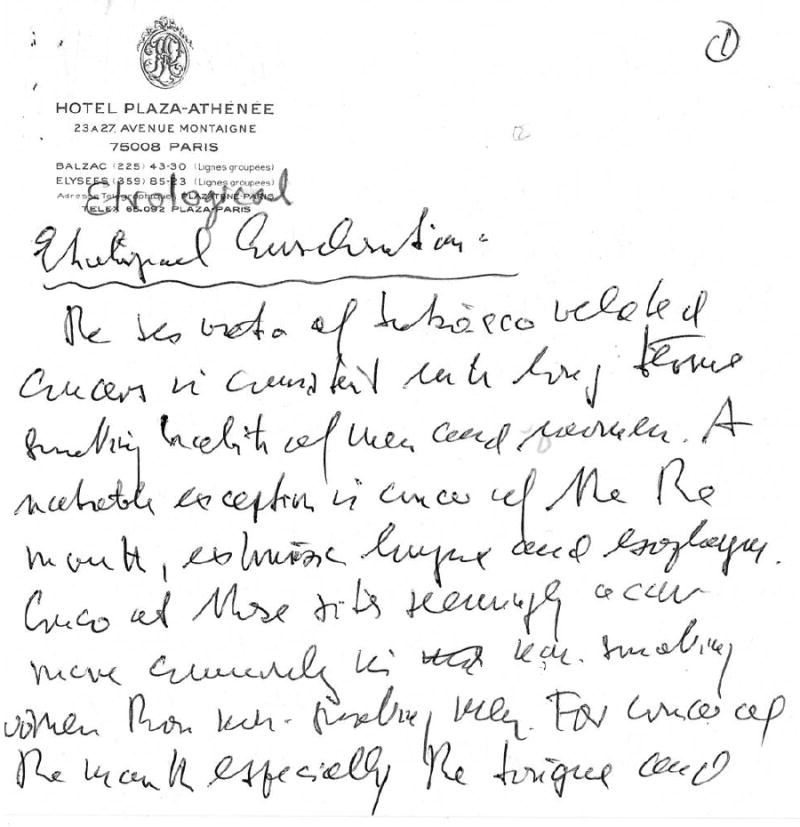

A note datelined Hotel Plaza-Athénée in Paris is of special interest. It consists of revisions to our 1977 paper "Comparative Epidemiology of Tobacco-Related Cancers"32 and refers to a 1957 paper of Wynder's that identified sideropenic dysphagia as a risk factor for cancer of the upper aerodigestive tract.33 In his note (and eventually our paper) he wrote: "The sex ratio of tobacco-related cancers is consistent with long term smoking habits of men and women. A notable exception is cancer of the mouth, extrinsic larynx, and esophagus. Cancers at these sites seemingly occur more commonly in non-smoking women than non-smoking men. For cancers of the mouth – especially the tongue and buccal cavity are affected. We believe this particular female susceptibility to be related to a subclinical type of Plummer-Vinson disease, a condition more common in women because of their inherently greater risk for iron deficiency." (Figure 2). Wynder always regarded his 1957 study as one of his most important findings because it shed light on a possible metabolic precursor of cancer, a very rare observation for those days.33 For many years afterwards he felt that this link was unjustifiably overlooked by many investigators.

FIGURE 2.

Ernst Wynder was not a theoretician but the opposite – a hands-on epidemiologist. While he loved talking to important people and delighted in his ability to have an impact on research policy, he was truly in his element when immersed in epidemiological data. He spent a great deal of effort making sure the staff had the latest technological tools they needed, but he also never forgot (or tired of reminding others of) the days of "flowsheeting," his practice dating from his Washington University days of manually transcribing patient questionnaire data onto sheets of accounting paper where he believed the trained eye (usually his own) could discern important patterns without the aid of chi-square tests or logistic regression. When a junior investigator sometimes failed to produce a desired table because of "computer problems," Wynder would grumble at first and then launch into the hundredth or so recitation of the simpler era of flowsheeting, adding (also for the hundredth time) that "as soon as I flowsheeted my tenth lung cancer case I knew I had something there."

While not shying away from studies of "hot" topics such as cellular telephones and brain cancer,34 Wynder firmly believed in a saying he attributed to E. V. Cowdry, Chair of Pathology at Washington University, author of one of the earliest textbooks on cancer etiology,35 and one of Wynder's mentors: common diseases have common causes. That belief kept him focused on tobacco and nutrition and their relation to the most common cancers: lung, colon, breast, and prostate. Even so, he had a strong skepticism about methods of dietary assessment, and always felt that the failure of analytic studies such as the Nurse's Health Study to report associations between cancer and diet were due to a combination of random misclassification related to the imprecision of food frequency questionnaires and the narrow range of nutrient intake within a given population. 36 I feel certain that he would have criticized the recent negative findings from the Women's Health on dietary fat and breast37 and colon cancer38 on similar grounds. This was one area where he felt that international comparisons at the ecological level provided better etiologic support than analytic studies, and he published many studies over a period of decades to make just that point. He was close friends with Takeshi Hirayama, Director of the Institute of Prevention of the National Cancer Institute in Tokyo, Japan, with whom he published a comparative study of cancer in the US and Japan in 1977,39 updated in 1991.40 Wynder attributed the striking differences in the incidence of breast, colon, and even lung cancer between the two countries to differences in diet, notably dietary fat.41 He developed a friendship with Kunio Aoki at the Aichi Cancer Research Institute in Nagoya, Japan, which resulted in our study which found that Japanese men with smoking habits similar to American men had considerably lower lung cancer risks.42

Most cancer researchers are familiar with Wynder's contributions in the fields of tobacco and nutrition, yet few know the extent to which he fervently sought to put this knowledge in the hands of those who he believed stood to gain most: children. Wynder married late in life and never had children of his own, yet he understood almost instinctively the importance of education and he liked to quote Ignatius of Loyola: "Give me a child until he is seven and he is mine for life." One of his most important projects was the development of a comprehensive school health curriculum which could be adopted in schools at all socioeconomic levels and in many different cultures and languages. This program underwent many modifications and iterations through the years, but was always referred to as the Know Your Body Program or KYB. This program was well under way when I arrived at AHF in the seventies, and much of my work in those early years involved computerization of the extensive knowledge testing and reporting associated with that program.

Much of Wynder's incessant travel was devoted to promoting the Know Your Body program abroad. Versions were implemented in a number of countries, including Japan and France43. In 1983, with the collaboration of the Israeli Ministry of Health, a two-year intervention was carried out with first-graders in sixteen Jerusalem schools which reported a decrease in serum total cholesterol and body mass index among both Jewish and Arab children.44

Wynder felt that a successful school health curriculum should be regarded as an intervention that needs to be evaluated in the same rigorous manner as, say, MRFIT, and accordingly sought out sympathetic principals and administrators in the New York City metropolitan area who could provide school sites for such tests.45,46 In one pilot trial he reported:

"After 6 years of intervention, the rate of initiation of cigarette smoking was significantly lower among subjects in intervention schools than among those in nonintervention schools. There was a significant net decrease in reported intake of saturated fat and a significant net increase in reported intake of total carbohydrate among subjects in intervention schools compared to those in nonintervention schools. These findings, if replicated, suggest that such programs are feasible and acceptable and may have a favorable effect on diet and prevention of cigarette smoking in children."47

Wynder continued to invest his personal effort in the Know Your Body program throughout the remainder of his life, writing as late as 1994:

"We place here particular emphasis on early comprehensive school health education and strongly suggest that such educational efforts must be on par with the teaching of other subjects since good healthy habits strongly affect both children's physical and mental development and thus contribute to a more productive future society."48

Wynder did not live to witness the current epidemic in obesity and risk in diabetes, but if he had I feel certain he would have attributed much of it to society's failure to implement the very educational programs that he worked so hard to develop. His efforts in this area accorded with his life-long wish, embodied in a quotation attributed to the ancient Greeks, that one's goal should be to die young as late in life as possible.

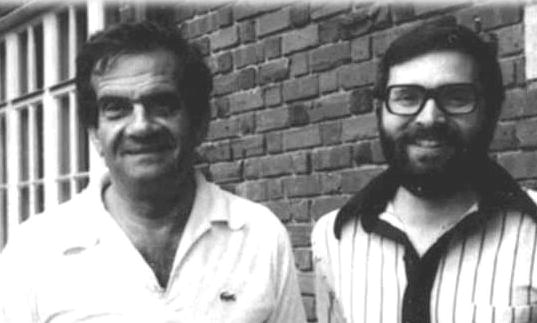

FIGURE 3.

Footnotes

Supported by USPHS Grants CA-68384, CA-17613, CA-32617, and CA-101598 from the National Cancer Institute.

References

- 1.Wynder EL. Primary prevention of cancer: planning and policy considerations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83(7):475–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.7.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wynder EL, Graham EA. Tobacco smoking as a possible etiologic factor in bronchiogenic carcinoma: a study of six hundred and eighty-four proved cases. JAMA. 1950;143:329–336. doi: 10.1001/jama.1950.02910390001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wynder EL, Graham EA, et al. Experimental Production of Carcinoma with Cigarette Tar. Cancer Research. 1953;13(12):855–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright GF, Wynder EL. Fractionation of Cigarette Tar. Cancer Research. 1955;2(1):55–55. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wynder EL, Graham EA, et al. Experimental Production of Carcinoma with Cigarette Tar .2. Tests with Different Mouse Strains. Cancer Research. 1955;15(7):445–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stellman SD. Ernst Wynder – A citation analysis. Prev Med. 2006;00:000–000. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Health Foundation Newsletter. [April/May, 1972]. Available on-line at http://tobaccodocuments.org/lor/81211109-1116.html. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anon Multiple risk factor intervention trial. Risk factor changes and mortality results. Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group. JAMA. 1982;248(12):1465–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anon Relationship between baseline risk factors and coronary heart disease and total mortality in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group. Prev Med. 1986;15(3):254–73. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(86)90045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morabia A, Wynder EL. Epidemiology and natural history of breast cancer. Implications for the body weight-breast cancer controversy. Surg Clin North Am. 1990;70(4):739–52. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)45179-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornfield J, Haenszel W, Hammond EC, Lilienfeld AM, Shimkin MB, Wynder EL. Smoking and Lung Cancer - Recent Evidence and a Discussion of Some Questions. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1959;22:173–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wynder EL, Cornfield J. Cancer of the Lung in Physicians. New England Journal of. Medicine 1953;248:441–444. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195303122481101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wynder EL, Stellman SD. Artificial Sweetener Use and Bladder-Cancer - Case-Control Study. Science. 1980;207:1214–1216. doi: 10.1126/science.7355283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doll R, Hill AB. Smoking and carcinoma of the lung: preliminary report. BMJ. 1950;2:739–748. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4682.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Smoking and Health. Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service. Publication No. 1103. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wynder EL, Stellman SD. Impact of Long-Term Filter Cigarette Usage on Lung and Larynx Cancer Risk - Case-Control Study. Journal of the National Cancer. Institute 1979;62:471–477. doi: 10.1093/jnci/62.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wynder EL. Tobacco and Health - a Review of the History and Suggestions for Public-Health Policy. Public Health. Reports 1988;103:8–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wynder EL. Interdisciplinary Centers for Tobacco-Related Cancer-Research - a Health-Policy Issue. American Journal of Public. Health 1995;85:14–16. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wynder EL. The past, present, and future of the prevention of lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7(9):735–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wynder EL, Stellman SD, Zang EA. High fiber intake - Indicator of a healthy lifestyle. JAMA-Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;275:486–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wynder EL, Weisburger JH, Ng SK. Nutrition - the Need to Define Optimal Intake as a Basis for Public-Policy Decisions. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82:346–350. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.3.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams CL, Bollella M, Wynder EL. A New Recommendation for Dietary Fiber in Childhood. Pediatrics. 1995;96:985–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taubes G. Epidemiology faces its limits. Science. 1995;269(5221):164–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7618077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordis L. Epidemiology. Third Edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szklo M. Design and conduct of epidemiologic studies. Prev Med. 1987;16(2):142–9. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szklo M, Nieto FJ. Epidemiology: Beyond the Basics. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feinleib M. Biases and weak associations. Prev Med. 1987;16(2):150–64. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stellman SD. Confounding. Prev Med. 1987;16(2):165–82. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stallones RA. The use and abuse of subgroup analysis in epidemiological research. Prev Med. 1987;16(2):183–94. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schlesselman JJ. "Proof" of cause and effect in epidemiologic studies: criteria for judgment. Prev Med. 1987;16(2):195–210. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wynder EL. Investigator bias and interviewer bias: the problem of reporting systematic error in epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:825–7. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wynder EL, Stellman SD. Comparative Epidemiology of Tobacco-Related Cancers. Cancer Research. 1977;37:4608–4622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wynder EL, Hultberg S, Jacobsson F, Bross IJ. Environmental Factors in Cancer of the Upper Alimentary Tract - a Swedish Study with Special Reference to Plummer-Vinson (Paterson-Kelly) Syndrome. Cancer. 1957;10:470–487. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195705/06)10:3<470::aid-cncr2820100309>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muscat JE, Malkin MG, et al. Handheld cellular telephone use and risk of brain cancer. JAMA. 2000;284(23):3001–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.23.3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cowdry EV. Etiology and Prevention of Cancer in Man. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wynder EL, Stellman SD. The "over-exposed" control group. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(5):459–61. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beresford SA, Johnson KC, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of colorectal cancer: the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. JAMA. 2006;295(6):643–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prentice RL, Caan B, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of invasive breast cancer: the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. JAMA. 2006;295(6):629–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wynder EL, Hirayama T. Comparative Epidemiology of Cancers of United-States and Japan. Preventive Medicine. 1977;6:567–594. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(77)90042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wynder EL, Fujita Y, Harris RE, Hirayama T, Hiyama T. Comparative Epidemiology of Cancer between the United-States and Japan - a 2nd Look. Cancer. 1991;67:746–763. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910201)67:3<746::aid-cncr2820670336>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wynder EL, Taioli E, Fujita Y. Ecologic Study of Lung-Cancer Risk-Factors in the United-States and Japan, with Special Reference to Smoking and Diet. Japanese Journal of Cancer Research. 1992;83:418–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1992.tb01944.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stellman SD, Takezaki T, Wang L, et al. Smoking and lung cancer risk in American and Japanese men: An international case-control study. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2001;10:1193–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choay P, Morla S. The Know Your Body program in France. Prev Med. 1981;10(2):149–58. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(81)90070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tamir D, Feurstein A, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in childhood: changes in serum total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein, and body mass index after 2 years of intervention in Jerusalem schoolchildren age 7–9 years. Prev Med. 1990;19(1):22–30. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(90)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walter HJ, Hofman A, et al. Modification of risk factors for coronary heart disease. Five-year results of a school-based intervention trial. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(17):1093–100. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198804283181704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walter HJ, Wynder EL. The development, implementation, evaluation, and future directions of a chronic disease prevention program for children: the "Know Your Body" studies. Prev Med. 1989;18(1):59–71. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(89)90054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walter HJ, Vaughan RD, et al. Primary prevention of cancer among children: changes in cigarette smoking and diet after six years of intervention. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81(13):995–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.13.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wynder EL. Principles of disease prevention from discovery to application. Soz Praventivmed. 1994;39:267–72. doi: 10.1007/BF01298837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]