Abstract

Understanding of the molecular architecture necessary for selective K+ permeation through the pore of ion channels is based primarily on analysis of the crystal structure of the bacterial K+ channel KcsA, and structure:function studies of cloned animal K+ channels. Little is known about the conduction properties of a large family of plant proteins with structural similarities to cloned animal cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (CNGCs). Animal CNGCs are nonselective cation channels that do not discriminate between Na+ and K+ permeation. These channels all have the same triplet of amino acids in the channel pore ion selectivity filter, and this sequence is different from that of the selectivity filter found in K+-selective channels. Plant CNGCs have unique pore selectivity filters; unlike those found in any other family of channels. At present, the significance of the unique pore selectivity filters of plant CNGCs, with regard to discrimination between Na+ and K+ permeation is unresolved. Here, we present an electrophysiological analysis of several members of this protein family; identifying the first cloned plant channel (AtCNGC1) that conducts Na+. Another member of this ion channel family (AtCNGC2) is shown to have a selectivity filter that provides a heretofore unknown molecular basis for discrimination between K+ and Na+ permeation. Specific amino acids within the AtCNGC2 pore selectivity filter (Asn-416, Asp-417) are demonstrated to facilitate K+ over Na+ conductance. The selectivity filter of AtCNGC2 represents an alternative mechanism to the well-known GYG amino acid triplet of K+ channels that has been identified as the critical basis for K+ over Na+ permeation through the pore of ion channels.

Crop productivity on about one-third of the world's arable land is limited by high soil salinity (Epstein et al., 1980). Current cultural practices on irrigated cropland will only add to this problem; up to 107 ha year–1 must be abandoned due to irrigation-associated rhizo-sphere Na+ accumulation (Flowers and Yeo, 1995). Our ability to deal with this vexing problem is currently limited by our lack of understanding, at the molecular level, of Na+ transport mechanisms in plants, and Na+/K+ discrimination by the ion channels that facilitate low affinity (i.e. at high soil Na+) uptake of Na+ into plants.

Complete sequencing of the Arabidopsis genome has led to new insights into the many families of cation transporters in plants (Maser et al., 2001). However, no Na+-selective channel has been identified to date in plants; the plant (Arabidopsis) genome contains no nucleotide sequence with significant homology to the (tetrodotoxin-sensitive) Na+ channel of animals (Catterall, 2000) or to the recently characterized dihydropyridine-sensitive Na+ channel (Ren et al., 2001) of prokaryotes. Current work suggests that Na+ influx (and toxicity) in major crop plants such as corn (Zea mays), barley (Hordeum vulgare), and wheat (Triticum aestivum) may be mediated, in part, by uptake through (voltage-independent) nonselective cation channels (Tyerman and Skerrett, 1999; Davenport and Tester, 2000; Demidchik et al., 2002). However, no cloned plant channel has yet been demonstrated to mediate inward Na+ currents. Molecular candidates for this ion uptake pathway could be some members of the recently cloned family of plant proteins that are homologous to animal cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (CNGCs).

Animal CNGCs are nonselective cation channels that are activated (allosterically) by cyclic nucleotides (activation by cyclic nucleotides is blocked by calmodulin; Molday, 1996). Animal CNGCs are only weakly voltage-gated (at saturating cyclic nucleotide, the I/V relationship is nearly linear; Zagotta and Siegelbaum, 1996). Animal CNGCs have nearly identical permeability and conductance profiles for Na+ and K+ (Gamel and Torre, 2000). Twenty different nucleotide sequences encoding putative CNGCs have been identified in Arabidopsis (Maser et al., 2001); orthologs of some of these putative channels have been cloned from crop plants (Schuurink et al., 1998; Maser et al., 2001). Members of this family of plant proteins bind to calmodulin (Schuurink et al., 1998; Arazi et al., 2000; Köhler and Neuhaus, 2000). Plant CNGCs are expressed in roots, where they have been demonstrated to affect cation uptake into plants (Sunkar et al., 2000; White et al., 2002, and refs. therein).

Not much is known about the ion selectivity profiles of plant CNGCs. We have shown that upon expression in Xenopus laevis oocytes, the Arabidopsis channels AtCNGC1 and -2, and the tobacco channel NtCBP4 demonstrate inwardly rectifying, noninactivating cAMP-dependent K+ currents (Leng et al., 1999, 2002). Interestingly, in contrast to all animal CNGCs (Flynn et al., 2001), AtCNGC2 was found not to appreciably conduct Na+ (Leng et al., 2002). In the work reported here, we extend this observation with protein structural modeling and experimental evaluation of the molecular basis for K+/Na+ discrimination by this plant channel.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structural Modeling of Plant CNGC Pore Regions

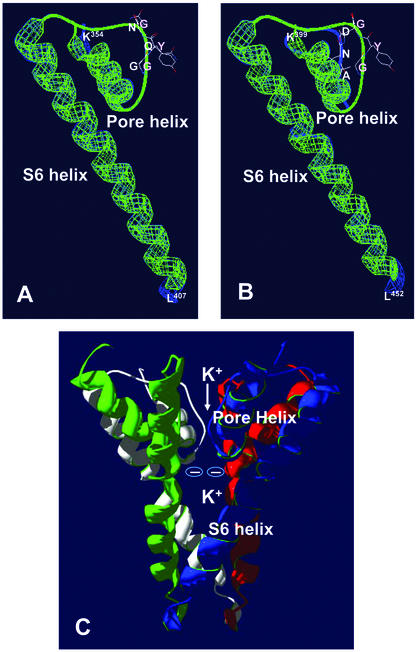

Sequence analysis suggests that animal (Flynn et al., 2001) and plant (Köhler et al., 1999) CNGC monomers retain many of the structural motifs common to the large superfamily of “P-loop” channel proteins that also includes voltage-gated K+-selective channels. K+-selective channels and CNGCs have six membrane-spanning regions (S1–S6) and a P-loop region. The P-loop region of K+-selective and cyclic nucleotide-gated nonselective cation channels is comprised of the S5 and S6 transmembrane segments and a pore region, or P-loop. We investigated the structure of the plant CNGC pore region by generating a three-dimensional computational model of the P-loop region of AtCNGC1 and AtCNGC2. Query sequences corresponding to the deduced AtCNGC1 and AtCNGC2 P-loop regions were submitted to a database of known protein crystal structures, identifying the crystal structure of the Streptomyces lividans K+ channel KcsA as the most appropriate modeling template. These three-dimensional models of the plant CNGC pore regions are shown superimposed on the KcsA pore in Figure 1, A and B. This modeling indicates that the best prediction of the plant CNGC pore structure has the P-loop dipping into the membrane from the extracellular surface as an α-helix (pore helix) and exiting back extracellularly as an uncoiled strand. The region of the channel forming this P-loop then forms another α-helix that traverses the membrane (i.e. the S6 transmembrane region) back toward the cell interior from the extracellular side of the membrane. Within the pore region of K+ channels such as KcsA, the amino acids in the uncoiled strand immediately C-terminal to the P-loop α-helix and upstream from the S6 transmembrane segment form the selectivity filter (Heginbotham et al., 1994).

Figure 1.

Model of the P-loop region of the plant CNGCs AtCNGC1 and AtCNGC2. A, Modeled AtCNGC1 P-loop region (corresponding to the sequence shown in Fig. 2) superimposed on the KcsA structure. KcsA is shown in green and AtCNGC1 in blue. B, Modeled AtCNGC2 P-loop region superimposed on the KcsA structure; color scheme is as in A. Core amino acids of the selectivity filters are displayed in wireframe format, colored in CPK, and annotated using single-letter abbreviations, the remaining structures are shown as ribbons. The amino acids K354 and K399 (identified in figure), are at the N terminus of the section of P-loop regions of AtCNGC1 and AtCNGC2 shown in this figure, respectively, and are positioned at the extracellular side of the pore helix as it dips into the membrane. This model predicts that the AtCNGC1 and AtCNGC2 polypeptides exit the membrane as uncoiled strands, and then traverse the membrane (S6 transmembrane domain) back toward the cell interior as α-helices with the amino acids L407 (AtCNGC1) or L452 (AtCNGC2) positioned at the intracellular end of the S6 transmembrane domain. Models shown in A and B are tertiary structures of single AtCNGC subunit polypeptides. C, Persistence of vision ray tracer image of the modeled quaternary structure of the P-loop regions of a tetrameric AtCNGC2 channel protein. An AtCNGC2 tetrameric sequence was threaded through the quaternary structure of the KcsA tetramer crystal structure to generate this model. This model indicates that four AtCNGC2 monomers are capable of forming a channel complex with the four subunits positioned such that the P-loop selectivity filters of each subunit align perpendicular to the membrane, forming the ion conduction pathway. This structure is presented with the top of the image corresponding to the extracellular side of channel protein.

It should be noted that native K+ channels such as KcsA are formed from four membrane-spanning subunits (Catterall, 1995), as is the case with animal CNGCs (Kaupp and Seifert, 2002). We generated a model of the ion-conducting pathway of a plant CNGC tetramer, as shown in Figure 1C. This computational modeling indicates that plant CNGCs are capable of forming the “inverted T-pee” quaternary structure of P-loop channels (Flynn et al., 2001), with the ion selectivity filters of each of the four subunits positioned perpendicular to the membrane and coalescing to form the ion conduction pathway.

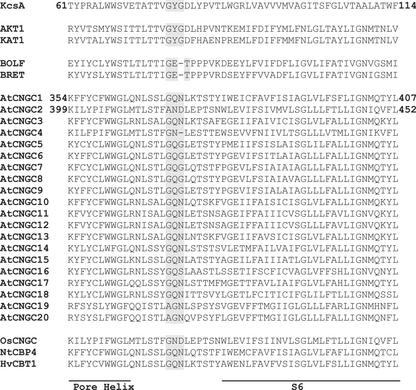

The elegant presentation of the first crystal structure of a K+ channel (KcsA) by MacKinnon and coworkers (Doyle et al., 1998) has provided a seminal elucidation of the molecular architecture of the pore ion selectivity filter. In large part due to this analysis, the K+ channel selectivity filter represents one of the biological enzyme motifs of a membrane protein for which our understanding of the molecular, and atomic structure:function relationship is most advanced (Miller, 2001). The selectivity filter of P-loop channels can be considered the “signature sequence” for subfamilies of these proteins (Heginbotham et al., 1994). MacKinnon and coworkers' analysis of the KcsA structure confirmed a large body of prior work, which suggested that the amino acid triplet GYG in the uncoiled strand within the pore is the selectivity filter of the K+ channel (Fig. 1, A and B). This selectivity filter is a remarkable structure. It facilitates ion conduction at rates (108 ion s–1) through the channel approaching that of the free ion diffusion potential in an aqueous solution, yet at the same time, it allows a high degree of discrimination (i.e. 10,000-fold) for K+ over Na+ conduction (Doyle et al., 1998). Doyle et al. (1998) presented this GYG triplet within the pore of channels as “absolutely required for K+ selectivity.” In line with this assertion, a broad range of K+-selective channel subfamilies from bacteria, plants, and animals retain this signature pore sequence. Morais-Cabral et al. (2001) extended this assertion in concluding that “The selectivity filter is the central structural element that defines a K+ channel, it's amino acid sequence is conserved in all K+ channels,” as did Jiang et al. (2002): “On the basis of the KcsA K+ channel structure, it seems that cation selectivity is an intrinsic property of the pore architecture”. Cyclic nucleotidegated nonselective cation channels cloned from animals do not retain this GYG motif (Zagotta and Siegelbaum, 1996). Animal CNGCs have the sequence GET (Zagotta and Siegelbaum, 1996), or G_ET (Doyle et al., 1998; Flynn et al., 2001) in this region of the pore (Fig. 2). This difference has been experimentally demonstrated to be the basis for the nonselective conduction of Na+ as well as K+ by these channel proteins (Zagotta and Siegelbaum, 1996; Flynn et al., 2001).

Figure 2.

Clustal alignment of the putative P-loop region of plant CNGCs with the corresponding region of the S. lividans K+ channel KcsA, the plant K+ channels AKT1 and KAT1, and the animal CNGCs BOLF and BRET. Arabidopsis CNGC (AtCNGC1–20) sequences were generated from the Munich Information Center for Protein Sequences Arabidopsis Database; accession numbers can be found in Maser et al. (2001). The putative rice (Oryza sativa; OsC-NGC) and barley (HvCBT1) CNGC GenBank accession numbers are AAK16188.1 and AJ002610, respectively. Accession numbers for the bovine olfactory (BOLF) and retinal (BRET) CNGCs, the tobacco CNGC (NtCBP4) and K+ channels can be found in Leng et al. (1999). The amino acids at positions corresponding to the selectivity filter of K+ channels and animal CNGCs, and the putative selectivity filters of plant CNGCs, are shaded. Horizontal bars denote portions of the P-loop region, which form the pore helix and S6 transmembrane (M2 in the case of KcsA) domain of both K+ channels (Doyle et al., 1998) and CNGCs (Flynn et al., 2001). The amino acid residue position numbers at each end of the sequences shown for KcsA, AtCNGC1, and AtCNGC2 correspond to the N and C termini of the corresponding sequences shown in Figure 1.

Plant CNGCs do not contain GYG or GET in this region of the pore. Our computational modeling (Fig. 1) indicates that the corresponding position in the P-loop regions of AtCNGC1 and AtCNGC2 is predicted to contain a GQN triplet or a AND triplet, respectively. It should be noted that the predicted selectivity filter of AtCNGC1 is present in the pore regions of many plant CNGCs, whereas the chemically distinct selectivity filter AND of AtCNGC2 (the most phylogenetically divergent of the AtCNGCs; Maser et al., 2001) is unique among this plant channel family (Fig. 2).

Protein modeling allows for a prediction of whether a polypeptide can fold into a specific tertiary structure within such constraints as (a) energy minimization predictions of the relative placement of amino acid side chains within the three-dimensional space occupied by the protein, (b) the presence of secondary structure motifs such as α-helices, β-strands, etc., and (c) possible amino acid residue interactions (hydrogen and ionic bonding, Van der Wall's and stacking forces, etc.). Models (such as those presented in Fig. 1) developed from threading primary peptide structures (sequences) through the known structures of crystallized proteins are by definition, therefore, only predictive of what a query protein's three-dimensional structure could be. However, they do provide insights that can focus experimental strategies. Within this context, the results of our modeling studies indicate that the AtCNGC1 and AtCNGC2 polypeptides (Fig. 1, A and B, respectively) are both capable of forming an uncoiled strand with a selectivity filter positioned near the outer mouth of the pore, but we note that this modeling highlights an intriguing difference between the two structures. The AtCNGC1 pore selectivity filter can assume a position relative to the pore helix similar to that of the selectivity filter of KcsA (i.e. the GQN and GYG triplets overlap for the most part; Fig. 1A). Conversely, our model of the AtCNGC2 P-loop region (Fig. 1B) suggests that the AtCNGC2 selectivity filter (AND) can be oriented within the ion-conducting pathway in a different position from the selectivity filter GYG triplet of KcsA. As indicated below from our experimental studies of the AtCNGC2 selectivity filter, it may represent a molecular paradigm significantly different from the selectivity filter of known P-loop channels. Nonetheless, our quaternary structure modeling (Fig. 1C) indicates that the P-loop regions of AtCNGC2 polypeptide subunits can still assemble into the “classical” ion conduction pathway of the tetrameric channel complex. The quaternary structural model of the AtCNGC2 tertramer ion-conducting pathway (Fig. 1C) suggests some other features consistent with P-loop channel tetramers. Within the ion-conducting pathway of the KcsA tetramer, the backbone amino acids of the pore helix are positioned such that the amide-carbonyl dipoles are oriented with the partial negative charges facing inward, along the ion-conducting pathway of the pore (Doyle et al., 1998). It is thought that these partial negative charges contribute to the stabilization of the dehydrated cation as it passes through the channel. Our model of the AtCNGC2 tetramer indicates a similar alignment of the amide-carbonyl dipoles of the pore helix amino acids; this orientation is symbolized by the negative charges shown within the ion-conducting pathway of the AtCNGC2 tetramer shown in Figure 1C.

Following the presently accepted convention regarding the selectivity filter of ion channels, neither of these AtCNGC pore region amino acid triplet sequences should be sufficient to confer selectivity for K+ over Na+ conduction to an ion channel protein. We continued our examination of the plant CNGC pore selectivity filter by expression of nucleotide sequences encoding CNGCs in X. laevis oocytes and human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells and evaluating the electrophysiological characteristics of the channels using voltage clamp analysis.

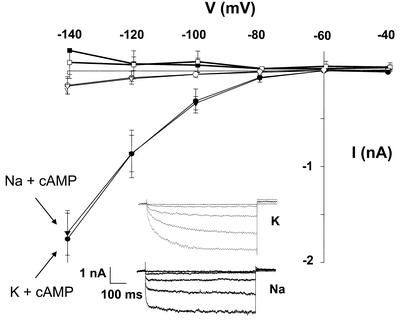

Na+ Conductance of AtCNGC1

HEK cells transfected with a cDNA encoding the Arabidopsis CNGC AtCNGC1 displayed cyclic nucleotide-activated currents with either K+ or Na+ in the perfusion bath that were not evident in control (non-transfected) cells (Fig. 3). AtCNGC1 currents are inward rectified and noninactivating (Fig. 3, inset), channel properties likely associated with cation uptake pathways in plants (Schroeder et al., 1994). Our three-dimensional modeling as shown in Figure 1A, in agreement with primary sequence alignments (Köhler et al., 1999; Leng et al., 2002), indicates that AtCNGC1 has the amino acid triplet GQN in the selectivity filter (as is the case with many plant CNGCs; Fig. 2). It is not surprising, therefore, that the results presented in Figure 3 are consistent with the conclusion that AtCNGC1 is an inward-rectified plant channel that conducts Na+ equally as well as K+. These data are the first demonstration of inward Na+ currents through a cloned plant ion channel. In conjunction with recent studies that document expression of AtCNGC1 in plant roots and demonstration that this protein provides an ion uptake pathway into plants for ions in the soil solution (Sunkar et al., 2000), the results presented here suggest the possibility that plant CNGCs such as AtCNGC1 may provide a physiologically significant Na+ uptake pathway for plants.

Figure 3.

AtCNGC1 conducts Na+ and K+. Whole-cell currents were recorded from HEK cells incubated in a perfusion bath containing 145 mm KCl or NaCl before (white symbols) or after (black symbols) addition of a lipophilic analog of cAMP (100 μm dibutyryl-cAMP) to the recording bath. Recordings were made from either control (non-transfected) cells in the presence of Na+ (□ and ▪) or cells transfected with the AtCNGC1 cDNA and incubated in K+ (○ and •) or Na+ (▿ and ▾) during recording. Holding potential was –60 mV, and recordings were made at command voltages between –140 and –40 mV in 20-mV increments. Results are shown as means (n ≥ 6 for all treatments) ± se. Inset, Representative time-dependent currents recorded from transfected cells in the presence of dibutyryl-cAMP and either K+ or Na+ in the perfusion bath. Recordings from non-transfected cells in the presence of K+ (not shown, see control treatments shown in Fig. 4A) were of a similar magnitude as those obtained in the presence of Na+.

High-affinity cation cotransporters such as the Arabidopsis protein AtHKT1 have been shown to transport Na+ upon expression in heterologous systems (Rubio et al., 1995) and likely contribute to Na+ uptake into plants from saline soils (Rus et al., 2001). However, other proteins present in the root provide additional pathways for Na+ influx into plants (Maathuis and Amtmann, 1999; Demidchik et al., 2002). The many plant K+ channels cloned to date (inward-rectified Shaker homologs such as KAT-, and AKT-type channels; outward-rectified Shaker homologs such as SKOR-type; and two-pore outward rectifiers such as KCO-type channels) appear to discriminate against Na+ conduction to an extent equal to that of cloned animal K+-selective channels (Schroeder et al., 1994; Davenport and Tester, 2000; Demidchik et al., 2002). Thus, at present, plant CNGCs such as AtCNGC1 and other members of this channel family (Fig. 2) with similar selectivity filter amino acid triplets (i.e. GQN) appear to be candidates for nonselective channels that contribute to the ion-conducting pathway allowing toxic levels of Na+ to be taken up by plants from saline soils (Maathuis and Sanders, 2001; Demidchik et al., 2002). In preliminary studies (i.e. recordings obtained from a single patch), Belagué et al. (2003) recently noted a weak K+ over Na+ selectivity of another member of this channel family (AtCNGC4) upon expression in oocytes.

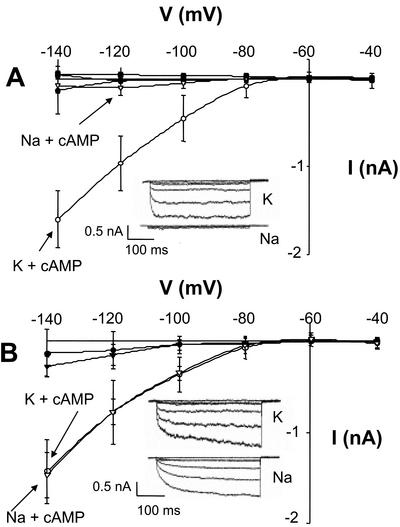

K+/Na+ Selectivity of AtCNGC2

In this report, we present an electrophysiological analysis of another plant CNGC (AtCNGC2), which has a putative pore selectivity filter unlike that found in AtCNGC1, animal CNGCs, or (plant, animal, or bacterial) K+-selective channels. AtCNGC2 has the amino acid triplet AND in the presumed pore selectivity filter where GYG is positioned in K+-selective channels (Fig. 1B). As noted previously in work from this lab using oocytes as a heterologous expression system (Leng et al., 1999), AtCNGC2 displays inward cAMP-dependent K+ currents (Fig. 4A) similar to those recorded for AtCNGC1 (Fig. 3). However, despite the fact that AtCNGC2 does not have the GYG motif in the pore selectivity filter, this plant channel does not conduct Na+; hyperpolarization-activated inward Na+ currents recorded from cells expressing AtCNGC2 were no greater than those recorded from control HEK cells (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

AtCNGC2 demonstrates selectivity for K+ over Na+ permeation due to unique amino acid residues in the pore selectivity filter. Assay conditions were the same as for Figure 3; whole-cell recordings from HEK cells before (black symbols) or after (white symbols) addition of 100 μm dibutyryl-cAMP to the perfusion bath are shown. Results are shown as means (n ≥ 6 for all treatments) ± se. A, Current/voltage relationship of (wild-type) AtCNGC2 in the presence of K+ (○ and •)orNa+ (▿ and ▾) in the recording bath. The control treatment (▪) was recorded from non-transfected cells in the presence of dibutyryl-cAMP and K+ in the perfusion bath. Inset, Representative time-dependent AtCNGC2 currents recorded in the presence of dibutyryl-cAMP and either K+ or Na+. B, Current/voltage relationship of (AtCNGC2N416D417ΔET) recorded in the presence (white symbols) or absence (black symbols) of dibutyryl-cAMP and either K+ (○ and •) or Na+ (▿ and ▾) in the recording bath. Inset, Representative time-dependent AtCNGC2N416D417ΔET currents recorded in the presence of K+ or Na+. A is reprinted from Leng et al. (2002) and is presented here to allow comparison of mutant channel currents with those recorded from the wild-type channel.

Although the AtCNGC2 pore selectivity filter triplet (AND; Fig. 1B) is not similar to the signature pore sequence (GYG) of K+ channels, it is also dissimilar to the triplet GET known to be the basis for Na+ permeation (equal to that of K+) by animal CNGCs (Flynn et al., 2001). Results shown in Figure 4 suggest the possibility that the pore selectivity filter of AtCNGC2 may represent an as-yet-unidentified basis for K+/Na+ discrimination by ion channels. Clearly, other functional domains of CNGC proteins physically interact with the pore to facilitate conduction (Flynn et al., 2001), and other parts of the P-loop region of CNGCs have been shown to affect K+/Na+ discrimination (Zagotta and Siegelbaum, 1996), so it would not necessarily follow that the triplet AND in the presumed pore of AtCNGC2 provides the basis for selective K+ (over Na+) conduction. The rest of the work in this report addresses this hypothesis.

Because the Ala in the pore of AtCNGC2 is chemically similar to the Gly of animal CNGCs, we reasoned that the N and D residues in the pore of AtCNGC2 could confer different permeation selectivity properties to the channel than the E and T at the corresponding positions in the pore of animal CNGCs. The conduction properties of AtCNGC2, with the ND in the pore mutated to the ET residues found in the selectivity filter of animal CNGCs is shown in Figure 4B. Mutation of these AtCNGC2 selectivity filter residues abolished selective K+ permeation; cAMP-activated Na+ currents recorded in the whole-cell configuration are as large as the K+ currents recorded from HEK cells expressing AtCNGC2N416D417ΔET. Further studies (not shown) indicated that mutating the N of the AtCNGC2 pore to E, and the D to a T individually resulted in the formation of nonfunctional channels and that the YG selectivity filter residues of K+-selective channels cannot replace the ND.

Recent work (Gamel and Torre, 2000) has identified the first of three Pro residues immediately C-terminal to the selectivity filter triplet of animal CNGCs (all animal CNGC α-subunits have the sequence GETPPP within the pore) as contributing to the structure of the cation conduction pathway of these channels. It should be noted that these results (Fig. 4B) indicate that the ET of the animal CNGC selectivity filter (which has been shown to be the basis for nonselective conduction of K+ and Na+; Flynn et al., 2001) can allow for such nonselective conduction in the absence of the pore Pro triplet.

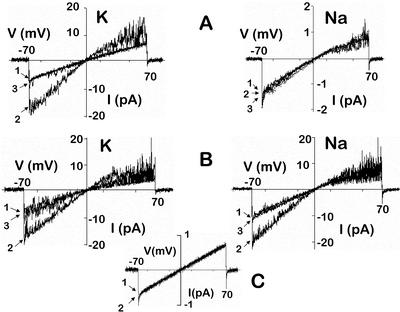

We used a second heterologous expression system to evaluate our contention that ND within the filter of AtCNGC2 provides a critical basis for K+/Na+ selectivity. The wild-type and mutant (AtCNGC2N416D417ΔET) channels were expressed in X. laevis oocytes, and ramp currents were recorded from membrane patches (Fig. 5). Application of cAMP to wild-type AtCNGC2 activated K+ currents (compare tracing 2 with tracing 1 in the left panel of Fig. 5A). The current tracing 1 represents the background or “leak” currents across these membrane patches and could be due to (a) current through AtCNGC2 that occurs in the absence of cAMP, (b) AtCNGC2 current evoked by endogenous cyclic nucleotide present in the oocyte and still associated with the membrane patch even after removal from the cell, or (c) current through endogenous oocyte channels (but see Fig. 5C; background or leak current in water injected oocytes is less than 1 μA at either –70 or +70 mV). No matter what caused the background leak current in these membrane patches, cAMP application resulted in a greater magnitude of K+ current (tracing 2) than was measured in the absence of cAMP (tracing 1). As was the case with measurements recorded in the whole-cell configuration from transfected HEK cells (Fig. 4), the AtCNGC2 current recorded from these membrane patches appears to be inwardly rectified; the channel(s) appears to be open for longer time periods at negative voltages (corresponding to current passing to the cytoplasm) than at positive voltages. Activation of AtCNGC2 current by exogenously added cAMP was reversible; upon washing of the membrane patch in bath solution with no added cAMP, the current (tracing 3) returns to background levels (tracing 1). In contrast to the cAMP-activated K+ current recorded from membrane patches pulled from oocytes injected with wild-type AtCNGC2 cRNA, no cAMP-dependent AtCNGC2 current was noted when pipette and bath solutions contained Na+ in place of K+ (Fig. 5A, right panel). In this case, no differences were noted in current tracings 1, 2, and 3. In contrast to the results obtained from the wild-type AtCNGC2 channel (Fig. 5A), application of cAMP evoked both K+ and Na+ current in membrane patches pulled from oocytes injected with AtCNGC2N416D417ΔET cRNA (Fig. 5B). As was the case with K+ currents through the wild-type channel (Fig. 5A), cAMP-activated K+ and Na+ currents through the mutant channel were inwardly rectified and reversible (Fig. 5B). In the patch configuration, the mutant channel, containing the ET found in the pore selectivity filter of animal CNGCs, displayed similar levels of cAMP-dependent K+ and cAMP-dependent Na+ currents (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Ramp recordings of wild-type and mutant AtCNGC2 currents. X. laevis oocytes were injected with AtCNGC2 (wild type; A), or AtCNGC2N416D417ΔET cRNA (B). Inside-out membrane patches were pulled from oocytes, and ramp recordings were obtained using pipette and bath solutions containing 90 mm KCl or NaCl (as noted), 0.2 mm K2EDTA (or Na2EDTA as appropriate), and 2 mm HEPES-KOH (NaOH as appropriate), pH 7.2, a holding potential of 0 mV, and a ramp (–70 mV to +70 mV) protocol. During recordings, membrane patches were constantly perfused, first with bath medium containing no cAMP (tracing 1), then with bath medium containing 100 μm cAMP (tracing 2), and then again with bath medium lacking cAMP (tracing 3). Data are presented with downward current corresponding to a positive charge passing from the extracellular side of the membrane (i.e. from the pipette) to the intracellular side of the membrane. Note the difference in amplitude between the current scales for the Na+ and K+ recordings in A. C, Using a similar protocol, recordings from water-injected oocytes displayed maximal inward K+ current of <1 pA at –70 mV and outward current of <1 pA at +70 mV, and no difference in current was observed in the absence (tracing 1) or presence (tracing 2) of 100 μm cAMP added to the bath perfusion medium.

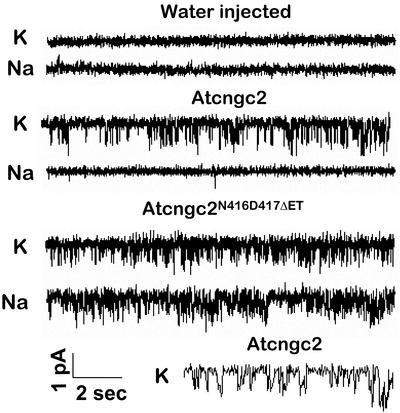

A similar experiment was undertaken with a different set of oocytes. In this case, recordings were also made using the inside-out patch configuration, and with K+ or Na+ (as noted) on both sides of the membrane, except recordings were made over longer time periods at one constant command voltage (Fig. 6). Similar results were obtained in this experiment. Application of ligand (cAMP) resulted in the occurrence of K+ current with the wild-type AtCNGC2 channel, whereas ligand evoked K+ and Na+ currents with AtCNGC2N416D417ΔET. The results presented in Figures 5 and 6, using a second heterologous expression system, provide confirmation of the work with HEK cells (Fig. 4) in demonstrating a high degree of selectivity for conduction of K+ and exclusion of Na+ by wild-type AtCNGC2 (in contrast to AtCNGC1; Fig. 3) and no K+/Na+ discrimination by the mutant AtCNGC2 channel. The results presented here are consistent with the contention that the triplet AND is positioned within the ion-conducting pore of the plant CNGC AtCNGC2 as a selectivity filter in a fashion corresponding to the GYG of K+ channels and that this pore selectivity filter provides the atomic architecture to the AtCNGC2 ion conduction pathway that allows for discrimination between K+ and Na+.

Figure 6.

Patch recordings from oocyte membranes in the presence of either K+ or Na+. Recordings were made in the presence of 90 mm KCl or NaCl (as noted) from oocytes injected with water, AtCNGC2 cRNA, or AtCNGC2N416D417ΔET cRNA. Pipette and bath solutions were the same as used in the experiment shown in Figure 5, except that 100 μm cAMP was present throughout recording during a –60 mV command voltage that was maintained throughout the recordings shown in this figure. The current and time bars in the lower left refer to all the recordings except the one at the bottom right. In this case, the K+ current recordings from a patch pulled from an oocyte injected with AtCNGC2 cRNA are reproduced with a time scale expanded by 10-fold to visualize individual channel opening events. The convention for showing channel opening is the same as used for Figure 5; for each recording, downward deflections show channel opening events.

Conclusion

Results in this report present the first electrophysiological analysis of an Na+-conducting ion channel cloned from plants (i.e. AtCNGC1). In addition, this work identifies the unique pore selectivity filter of AtCNGC2 as facilitating the permeation of K+ and exclusion of Na+ through the pore of a channel protein, in a fashion similar to the GYG triplet of Shaker-like channels. Unraveling how the AtCNGC2 selectivity filter facilitates selective K+ conduction could provide unique insights into our currently developing understanding of how ion channels undertake their elegant and fundamentally important function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Computational Analysis and Structural Modeling

A list of peptide sequences corresponding to characterized and putative Arabidopsis CNGCs was generated from the Munich Information Center for Protein Sequences Arabidopsis Database (http://mips.gsf.de/proj/thal/). In addition, peptide sequences corresponding to animal CNGCs and plant K+ channel and CNGCs (other then Arabidopsis) were retrieved via BLAST screens of the nonredundant database at GenBank through the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Multiple amino acid sequence alignments were performed using ClustalX software (Thompson et al., 1997) with the default parameters.

Three-dimensional computational models of the P-loop region corresponding to both AtCNGC1 (amino acids Lys-354 to Leu-407) and AtCNGC2 (amino acids Lys-399 to Leu-452) were generated by threading these sequences (as separate projects), through the crystal structure of the Streptomyces lividans KcsA K+ channel (protein database [PDB] record 1BL8A) and generating homology models for the two plant channels. Initially, the corresponding amino acid sequences were submitted to the Swiss-model Blast Protein Modeling Server (Guex and Peitsch, 1997), which searches the ExNRL-3D database. The query identified PDB record 1BL8A for both AtCNGC1 and AtCNGC2 as an appropriate modeling template. The PDB record was downloaded for subsequent analysis, and the experimental sequences were then submitted back through the Swiss-model Blast Protein Modeling Server using the 1BL8A record as a template to generate three-dimensional structural models of the AtCNGC1 and AtCNGC2 pore regions. Using the SwissModel “First Approach” mode with a lower BLAST P (N) limit of 0.00001, positive structures were rendered and analyzed locally through the Swiss-PdbViewer version 3.5 (Glaxo Wellcome Experimental Research). Reproductions of the modeled structures were loaded into Microsoft PowerPoint as bitmap files and annotated. In addition, a proposed three-dimensional computational model representing the AtCNGC2 homotetramer was generated using the quaternary structure of KcsA (1BL8) as a modeling template. The model was generated precisely as described in the Swiss-model Protein Modeling Server oligomer modeling strategy (http://www.expasy.org/swissmod/SWISS-MODEL.html). The AtCNGC2 P-loop region (amino acids Lys-399 to Leu-452) was constructed into four repeats as a text file with appropriate annotations and submitted to the Swiss-model Protein Modeling Server. Using the “optimize project mode,” a quaternary structure was generated and subsequently rendered as a persistence of vision ray tracer image. The image was then annotated locally.

Channel Expression and Electrophysiological Analysis in HEK Cells

Construction of an AtCNGC1 expression plasmid for HEK cell (HEK cell line HEK 293, American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) transient transfection was performed by restriction digestion of a pBluescript II SK+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) plasmid containing the AtCNGC1 coding sequence (Leng et al., 2002) with EcoRI and NotI; the resultant AtCNGC1 encoding cDNA was ligated into EcoRI- and NotI-digested pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Construction of an AtCNGC2 expression plasmid for transient transfection of HEK cells was performed as previously described (Leng et al., 2002). Mutations were incorporated into the AtCNGC2 coding sequence using the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) following the procedures described in the instructional manual (revision no. 108005h). The following sense and antisense oligonucleotide primers, respectively, containing the appropriate mutations were generated to construct AtCNGC2N416D417ΔET: GACTCTCAGCACATTTGCGGAGACTCTTGAGCCCACAAGC and GCTTGTGGGCTCAAGAGTCTCCGCAAATGTGCTGAGAGTC. Unless otherwise noted, all DNA manipulations were performed using standard methods (Ausubel et al., 1987). Heterologous expression of AtCNGC1 and AtCNGC2 in HEK cells and subsequent voltage clamp measurements were performed as previously described (Leng et al., 2002). Any modifications are presented in figure legends. Solutions used for all HEK cell recordings contained: 10 mm HEPES-K(Na) OH, pH 7.4, 10 mm Glc, and 0.1 mm MgCl2 (bath solution); or 145 mm N-methyl-d-glucamine, 10 mm HEPES-K(Na) OH, pH 7.4, and 0.5 mm MgCl2 (pipette solution). Additions of NaCl or KCl, and dibutyryl-cAMP are noted in figure legends.

On the day of recording, cells were washed with maintenance medium and incubated with M450 Dynabeads conjugated with anti-CD8 antibody at 1 μL 2 mL–1 (Dynal, Oslo). Successful transfection was ascertained by the adherence of Dynabeads to a cell (Jurman et al., 1994). These cells were used for electrophysiological recordings in the whole-cell configuration at room temperature. It should be noted that whereas approximately 40% of beaded cells cotransfected with an animal CNGC (used as a control) yielded cyclic nucleotide-dependent currents, only approximately 5% of beaded cells cotransfected with AtCNGC2 yielded cyclic nucleotide-dependent currents (data not shown); we do not know the basis for this difference in successful expression of plant versus animal CNGCs in HEK cells. Also germane to the work presented in this report is our observation of several different inwardly conducting K+ channels in control (i.e. non-transfected) HEK cells. We have observed inward K+ channels in these control HEK cells with conductances of 4, 13, 8, and 29 pS (data not shown). Due to these background inward K+ currents in control HEK cells, we focused on using oocytes for patch recordings of AtCNGC2 single-channel events in the work reported here.

Channel Expression and Electrophysiological Analysis in X. laevis Oocytes

The AtCNGC2 coding sequence in a pZL plasmid (described by Leng et al. [1999]) was used to generate a mutant construct (AtCNGC2N416D417ΔET) using the site-directed mutagenesis protocol described above. Full-length sense RNA encoding methylated, capped runoff transcripts were generated from pZL-AtCNGC2 and pZL-AtCNGC2N416D417ΔET using the Epicentre AmpliScribe T7 High Yield Transcription Kit (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, WI). Oocytes were harvested from Xenopus laevis frogs, microinjected with AtCNGC2 and AtCNGC2N416D417ΔET cRNA, and used (after removal of the vitelline layer) for patch recordings (inside-out configuration; cytoplasmic portion of the channel exposed to the perfusion bath) as described previously (Leng et al., 2002). In some experiments, a ramp command protocol was used (+70 to –70 mV over 4 s) during measurement of currents. During patch recordings, cAMP was delivered to the cytoplasmic portion of the channel from a gravity-driven multibarrel perfusion system. Time between individual ramp recordings taken on the same membrane patch was dependent on our perfusion system, and was a minimum of several seconds. Recording and bath solutions contained 90 mm KCl or NaCl (as noted in figure legends), 0.2 mm EDTA, and 2 mm HEPES-K(Na) OH, pH 7.2.

Distribution of Materials

In all cases, reagents and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis), unless otherwise noted. Upon request, all novel materials described in this publication will be made available in a timely manner for noncommercial research purposes, subject to the requisite permission from any third-party owners of all or parts of the material. Obtaining any permissions will be the responsibility of the requestor.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.103.020560.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant no. MCB–0090675 to G.A.B.). This is a publication from the Storrs Agricultural Experiment Station.

References

- Arazi T, Kaplan B, Fromm H (2000) A high-affinity calmodulin-binding site in a tobacco plasma-membrane channel protein coincides with a characteristic element of cyclic nucleotide-binding domains. Plant Mol Biol 42: 591–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K (1987) Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York

- Belagué C, Lin B, Alcon C, Flottes G, Malmström, Köhler C, Neuhaus G, Pelletier G, Gaymard F, Roby D (2003) HLM1, and essential signaling component in the hypersensitive response, is a member of the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel ion channel family. Plant Cell 15: 365–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA (1995) Structure and function of voltage-gated ion channels. Annu Rev Biochem 64: 493–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA (2000) From ionic currents to molecular mechanisms: the structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron 26: 13–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport RJ, Tester M (2000) A weakly voltage-dependent, nonselective cation channel mediates toxic sodium influx. Plant Physiol 122: 823–834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V, Davenport RJ, Tester M (2002) Nonselective cation channels in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 53: 67–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DA, Cabral JM, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Cohen SL, Chait BT, MacKinnon R (1998) The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K conduction and selectivity. Science 280: 69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein E, Norlyn JD, Rush DW, Kingsbury RW, Kelly DB, Cunningham GA, Wrona AF (1980) Saline culture of crops: a genetic approach. Science 210: 399–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers TJ, Yeo AR (1995) Breeding for salinity resistance in crop plants: Where next? Aust J Plant Physiol 22: 875–884 [Google Scholar]

- Flynn GE, Johnson JP, Zagotta WN (2001) Cyclic nucleotide-gated channels: shedding light on the opening of a channel pore. Nat Rev Neurosci 2: 643–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamel K, Torre V (2000) The interaction of Na(+) and K(+) in the pore of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Biophys J 79: 2475–2493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N, Peitsch MC (1997) SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: and environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18: 2714–2723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heginbotham L, Lu Z, Abramson T, MacKinnon R (1994) Mutations in the K+ channel signature sequence. Biophys J 66: 1061–1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Lee A, Chen J, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R (2002) Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Nature 417: 515–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurman ME, Boland LM, Liu Y, Yellen G (1994) Visual identification of individual transfected cells for electrophysiology using antibody-coated beads. Biotechniques 17: 876–881 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupp UB, Seifert R (2002) Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Physiol Rev 82: 769–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler C, Merkle T, Neuhaus G (1999) Characterization of a novel gene family of putative cyclic nucleotide- and calmodulin-regulated ion channels in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 18: 97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler C, Neuhaus G (2000) Characterization of calmodulin binding to cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels from Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett 471: 133–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng Q, Mercier RW, Hua B-G, Fromm H, Berkowitz GA (2002) Electrophysiological analysis of cloned cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Plant Physiol 128: 400–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng Q, Mercier RW, Yao W, Berkowitz GA (1999) Cloning and first functional characterization of a plant cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel. Plant Physiol 121: 753–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maathuis FJM, Amtmann A (1999) K+ nutrition and Na+ toxicity: the basis of cellular K+/Na+ ratios. Ann Bot 84: 123–133 [Google Scholar]

- Maathuis FJM, Sanders D (2001) Sodium uptake in Arabidopsis thaliana roots is regulated by cyclic nucleotides. Plant Physiol 127: 1617–1625 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maser P, Thomine S, Schroeder JI, Ward JM, Hirschi K, Sze H, Talke IN, Amtmann A, Maathuis FJ, Sanders D et al. (2001) Phylogenetic relationships within cation transporter families of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 126: 1646–1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C (2001) See potassium run. Nature 414: 23–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molday RS (1996) Calmodulin regulation of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Curr Opin Neurobiol 8: 445–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morais-Cabral JH, Zhou Y, MacKinnon (2001) Energetic optimization of ion conduction rate by the K+ selectivity filter. Nature 414: 37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren D, Navarro B, Xu H, Yue L, Shi Q, Clapham DE (2001) A prokaryotic voltage-gated sodium channel. Science 294: 2372–2375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio F, Gassmann W, Schroeder JI (1995) Sodium-driven potassium uptake by the plant potassium transporter HKT1 and mutations conferring salt tolerance. Science 270: 1660–1663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rus A, Yokoi S, Sharkhuu A, Reddy M, Lee B-H, Matsumoto TK, Koiwa H, Zhu J-K, Bressan RA, Hasegawa PM (2001) AtHKT1 is a salt tolerance determinant that controls Na+ entry into plant roots. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 14150–14155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Ward JM, Gassmann W (1994) Perspectives on the physiology and structure of inward-rectifying K+ channels in higher plants: biophysical implications for K+ uptake. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 23: 441–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuurink RC, Shartzer SF, Fath A, Jones RL (1998) Characterization of a calmodulin-binding transporter from the plasma membrane of barley aleurone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 1944–1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunkar R, Kaplan B, Bouche N, Arazi T, Dolev D, Talke IN, Maathuis FJM, Sanders D, Bouchez D, Fromm H (2000) Expression of a truncated tobacco NtCBP4 channel in transgenic plants and disruption of the homologous Arabidopsis CNGC1 gene confer PB2+ tolerance. Plant J 24: 533–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG (1997) The ClustalX windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 24: 4876–4882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyerman SD, Skerrett IM (1999) Root ion channels and salinity. Sci Hort 78: 175–235 [Google Scholar]

- White PJ, Bowen HC, Demidchik V, Nichols C, Davies JM (2002) Genes for calcium-permeable channels in the plasma membrane of plant root cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1564: 299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagotta WN, Siegelbaum SA (1996) Structure and function of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Annu Rev Neurosci 19: 235–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]