Abstract

C4 plants are rare in the cool climates characteristic of high latitudes and elevations, but the reasons for this are unclear. We tested the hypothesis that CO2 fixation by Rubisco is the rate-limiting step during C4 photosynthesis at cool temperatures. We measured photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence from 6°C to 40°C, and in vitro Rubisco and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase activity from 0°C to 42°C, in Flaveria bidentis modified by an antisense construct (targeted to the nuclear-encoded small subunit of Rubisco, anti-RbcS) to have 49% and 32% of the wild-type Rubisco content. Photosynthesis was reduced at all temperatures in the anti-Rbcs plants, but the thermal optimum for photosynthesis (35°C) did not differ. The in vitro turnover rate (kcat) of fully carbamylated Rubisco was 3.8 mol mol–1 s–1 at 24°C, regardless of genotype. The in vitro kcat (Rubisco Vcmax per catalytic site) and in vivo kcat (gross photosynthesis per Rubisco catalytic site) were the same below 20°C, but at warmer temperatures, the in vitro capacity of the enzyme exceeded the realized rate of photosynthesis. The quantum requirement of CO2 assimilation increased below 25°C in all genotypes, suggesting greater leakage of CO2 from the bundle sheath. The Rubisco flux control coefficient was 0.68 at the thermal optimum and increased to 0.99 at 6°C. Our results thus demonstrate that Rubisco capacity is a principle control over the rate of C4 photosynthesis at low temperatures. On the basis of these results, we propose that the lack of C4 success in cool climates reflects a constraint imposed by having less Rubisco than their C3 competitors.

C4 plants often dominate the warm climate regions of the earth when they have access to at least moderate light intensities (Sage et al., 1999). Conversely, C4 species are relatively rare in the cool climates characteristic of high latitudes or high elevations (Teeri and Stowe, 1976; Tieszen et al., 1979; Rundel, 1980; Long, 1983; Sage et al., 1999). In North America, temperature is the best predictor of the success of C4 grasses, which rarely occur when the minimal temperature of the warmest month of the growing season is below 8°C (Teeri and Stowe, 1976). Globally, C4 plants are rare at latitudes and elevations where the average growing season temperatures are less than approximately 16°C (Sage et al., 1999). The transition from C4- to C3-dominated landscapes generally occurs between 30°N and 40°N and between 1,500 and 3,000 m elevation (Sage et al., 1999).

The reason for the relative lack of C4 plants in cool regions remains unclear. The lower quantum yield of photosynthesis (ϕCO2, the initial slope of the light-response curve) in C4 versus C3 species at low temperatures has been proposed to account for the differences in the biogeography of the two pathways (Ehleringer and Björkman, 1977; Ehleringer, 1978). However, differences in quantum yield only effect carbon uptake when light is limiting, and in plant canopies CO2 assimilation is a function of both light-saturated and light-limited photosynthetic rates (Ehleringer, 1978; Long, 1999). Alternatively, one or more of the carbon-concentrating reactions of the mesophyll might be inherently chilling sensitive. Pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase (PPDK, EC 2.7.9.1) and phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) carboxylase (PEPCase, EC 4.1.1.31) can both dissociate below 8°C to 12°C in vitro (Sugiyama and Boku, 1976; Edwards et al., 1985; Krall and Edwards, 1993). However, considerable species and ecotypic variability has been noted, and these steps are not fundamentally prone to failure at low temperatures in vivo (Leegood and Edwards, 1996; Matsuba et al., 1997).

The possibility that the bundle sheath reactions may limit C4 photosynthesis at suboptimal temperatures has received less attention. Björkman and Pearcy (1971) found that the activation energy (Ea) of photosynthesis was similar to that of Rubisco (EC 4.1.1.39) in several warm-climate C3 and C4 species. Variation in Rubisco activity was correlated with differences in the photosynthetic capacity of Atriplex lentiformis (Torr.) Wats. grown at different temperatures (Pearcy, 1977). In Bouteloua gracilis Lag. and Muhlenbergia montanum (Nutt.) A.S. Hitch., the light-saturated net photosynthetic rate and the maximal in vitro Rubisco activity are equivalent below 17°C and 22°C, respectively (Pittermann and Sage, 2000, 2001). These findings indicate that Rubisco capacity can limit the rate of C4 photosynthesis below approximately 20°C.

A Rubisco limitation can be quantified if the amount of the enzyme is changed without affecting the activities of other enzymes (Stitt and Schulze, 1994; Stitt, 1995). This enables determination of a flux control coefficient for Rubisco (Cra) within the context of the carbon assimilation pathway (Kacser and Burns, 1973; Stitt, 1995). A Cra of 1 indicates complete control of photosynthetic flux by Rubisco; a 10% change in the amount of enzyme will result in a 10% change in the flux through the pathway. A control coefficient between zero and one would indicate that the control of photosynthesis is shared between Rubisco and other processes. To determine Cra, a series of plants with differences in the content of Rubisco is needed (Stitt and Schulze, 1994). Antisense molecular techniques provide a means of meeting this requirement.

In the C4 dicot Flaveria bidentis L. Kuntze, Rubisco content has been reduced with antisense-RNA constructs targeting the nuclear-encoded small-subunit of Rubisco (RbcS; Chitty et al., 1994; Furbank et al., 1996, 1997). The amounts of other photosynthetic enzymes are not effected by the transformation (Furbank et al., 1996). Reducing Rubisco by antisense in F. bidentis results in plants that have reduced steady-state photosynthetic rates under a range of conditions (Furbank et al., 1996; Siebke et al., 1997; von Caemmerer et al., 1997). Anti-RbcS F. bidentis has been used to show that Rubisco is an important control over C4 photosynthesis at temperatures near the thermal optimum, where Cra was as high as 0.7 (Furbank et al., 1997). The effect of temperature variation on this control is unknown.

In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that Rubisco is the primary rate-limiting step during C4 photosynthesis at low temperatures. We used three F. bidentis genotypes with a 3-fold difference in Rubisco content. To examine the nature of the rate limitation during the temperature response of C4 photosynthesis, we measured gas exchange and chlorophyll a fluorescence across a range of temperatures from 6°C to 40°C and the in vitro activities of Rubisco and PEPCase from 0°C to 42°C. To quantify the control of CO2 assimilation by Rubisco and whether this control is affected by temperature, we determined the Cra at temperatures ranging from 6°C to 40°C.

RESULTS

The antisense constructs led to significant reductions in the amount of Rubisco present in F. bidentis leaves (Table I). The 136-13 and 141-1 anti-RbcS lines had 49% and 32% of the wild-type Rubisco content, respectively. The Rubisco turnover rate (kcat) did not differ between any of the lines, indicating that the antisense constructs had no effect on the kinetics of the enzyme. There was no difference in the activity of PEPCase between the genotypes (Table I). In each genotype, the Arrhenius plots for Rubisco and PEPCase indicated enzyme dissociation at low temperatures in vitro (Table I). The Ea of Rubisco increased from approximately 57 to 100 kJ mol–1 between 12°C and 18°C, whereas the Ea of PEPCase increased from 71 to 180 kJ mol–1 at similar temperatures. The wild-type plants had higher chlorophyll content than the anti-RbcS lines, but there were no changes in the ratio of chlorophyll a/b (Table I).

Table I.

Biochemical characteristics of Flaveria bidentis wild type and anti-RbcS plants

The concentration of Rubisco active sites was determined by the 14CABP-labeling assay described in “Materials and Methods.” The kcat and enzyme activity data are values at 24°C. The Rubisco kcat and PEP carboxylase activity values were determined by the incorporation of 14C into acid-stable products. Activation energies were calculated as described by Berry and Raison (1981) across the temperature ranges indicated by superscript letters. Chlorophyll determinations follow Porra et al. (1989). Each value represents the mean (± se) of four or five measurements. Values with different capital letters are statistically different from each other (P < 0.05, Tukey).

| Rubisco

|

PEP Carboxylase

|

Gross CO2 Assimilation

|

Chlorophyll

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant | Catalytic Sites | kcat | Ea | Activity | Ea | Eaa | Content | a/b |

| μmol m-2 | mol mol-1 s-1 | kj mol-1 | μmol m-2 s-1 | kj mol-1 | kj mol-1 | μmol m-2 | ||

| Wild type | 13.2 ± 0.9A | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 100.6 ± 2.0b | 159.9 ± 6.8 | 175.2 ± 3.8b | 72.7 ± 1.4A | 592 ± 59A | 3.7 ± 0.1 |

| 56.1 ± 1.4c | 71.6 ± 1.0c | |||||||

| anti-RbcS 136-13 | 6.5 ± 0.9B | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 97.4 ± 6.1b | 186.3 ± 13.5 | 193.6 ± 3.8b | 87.6 ± 1.6B | 453 ± 37B | 3.7 ± 0.2 |

| 57.0 ± 2.1c | 69.4 ± 3.4c | |||||||

| anti-RbcS 141-1 | 4.2 ± 0.5B | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 100.9 ± 2.4b | 146.9 ± 13.3 | 183.4 ± 6.6b | 96.2 ± 2.6C | 469 ± 41AB | 3.8 ± 0.2 |

| 59.3 ± 1.1c | 74.0 ± 1.9c | |||||||

Measured between 5°C and 30°C. b Measured between 0°C and 12°C. c Measured between 18°C and 42°C.

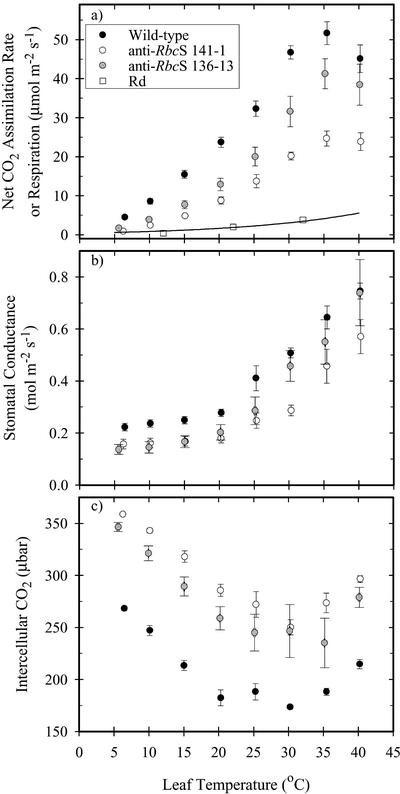

Reducing the amount of Rubisco by antisense led to a large reduction in the net CO2 assimilation rate (A) relative to the wild type at all measurement temperatures (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, the ratio of wild type to antisense photosynthesis increased as leaf temperature was reduced. F. bidentis had a photosynthetic thermal optimum of about 35°C when grown under these conditions, regardless of genotype (Fig. 1a). Dark respiration (Rd) did not vary with genotype (P = 0.67, ANOVA; Fig. 1a). The Ea of net photosynthesis was about 20% higher in the anti-RbcS lines (Table I). The antisense lines had lower stomatal conductance than the wild type below 20°C (Fig. 1b) but maintained a higher intercellular CO2 (Ci) across the range of temperatures measured, due to their greatly reduced photosynthetic rates (Fig. 1c). The Ci corresponding to an ambient CO2 of 370 μbar was sufficient to saturate photosynthesis at each measurement temperature in all genotypes (data not shown). Stomatal conductance was relatively stable in each genotype below 20°C, and Ci rose markedly as temperature declined below this point.

Figure 1.

The temperature responses of the rates of net CO2 assimilation

and Rd (a), stomatal conductance (b), and the partial pressure of Ci (c) in

F. bidentis wild type (•) and anti-RbcS (○

and  ). Photosynthesis was measured at a temperature- and

genotype-dependent PPFD that was just sufficient to saturate photosynthesis at

370 μbar CO2 and 200 mbar O2. Each point represents

the mean (± se) of measurements on five different leaves. Rd

was determined as the y intercept of the light response of

photosynthesis in the wild-type and 141-1 lines. Respiration did not differ

between genotypes, and pooled values are shown here. The relationship between

Rd and temperature is described by Rd =

3.76e–3 T2 +

5.74e–4 T +

8.56e–9 (where T is leaf

temperature [°C], R2 = 0.927). This was used to

correct the net assimilation for respiration in all ensuing calculations.

). Photosynthesis was measured at a temperature- and

genotype-dependent PPFD that was just sufficient to saturate photosynthesis at

370 μbar CO2 and 200 mbar O2. Each point represents

the mean (± se) of measurements on five different leaves. Rd

was determined as the y intercept of the light response of

photosynthesis in the wild-type and 141-1 lines. Respiration did not differ

between genotypes, and pooled values are shown here. The relationship between

Rd and temperature is described by Rd =

3.76e–3 T2 +

5.74e–4 T +

8.56e–9 (where T is leaf

temperature [°C], R2 = 0.927). This was used to

correct the net assimilation for respiration in all ensuing calculations.

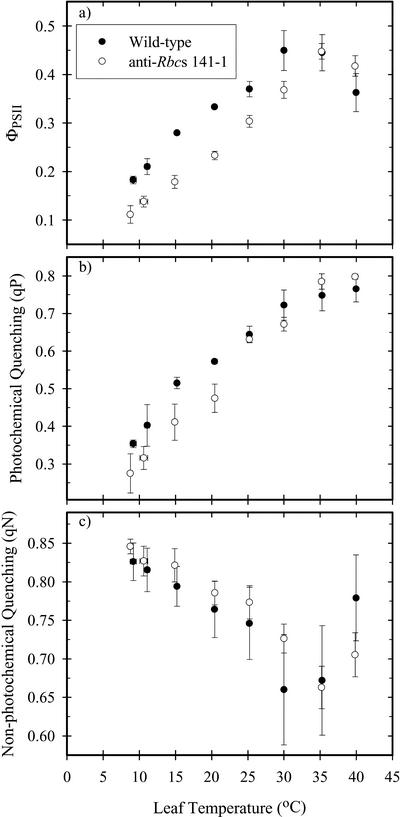

At 30°C, the ratios of variable to maximal fluroescence (Fv/Fm) were 0.80 ± 0.01 and 0.82 ± 0.01 (+ se; n = 8) for the wild type and 141-1 lines, respectively. At a light intensity of 1,500 μmol m–2 s–1, the wild-type leaves had a higher quantum yield of photosystem II (PSII; ΦPSII) than the anti-RbcS leaves at temperatures below the thermal optimum (Fig. 2a). The same pattern was detected when the temperature curves were measured under illumination that was just saturating, although in that case ΦPSII at low temperatures (<15°C) was about 15% higher than the data obtained at a constant PPFD of 1,500 μmol m–2 s–1 (data not shown). The wild-type leaves maintained a greater proportion of open PSII than the antisense plants below 25°C, as indicated by the higher photochemical quenching (qP) values (Fig. 2b); at higher temperatures there was no difference between the two groups. There were no statistical differences in non-photochemical quenching between the two genotypes (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

The temperature responses of the quantum yield of PSII (a; ΦPSII), photochemical quenching (b; qP), and non-photochemical quenching (c; qN) in F. bidentis wild type (•) and anti-RbcS (141-1, ○). Measurements were made at a constant PPFD of 1,500 μmol m–2 s–1, 370 μbar CO2, and 200 mbar O2. Each point represents the mean (± se) of measurements on three different leaves.

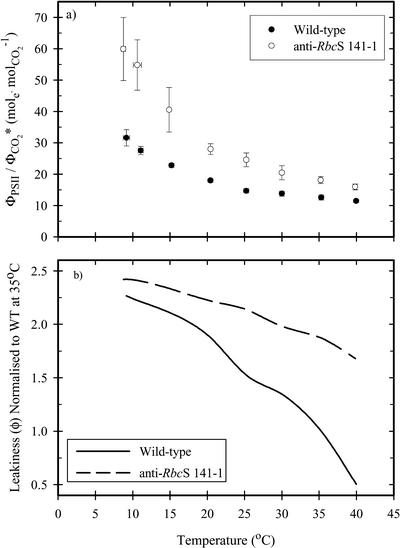

The instantaneous quantum requirement of PSII per CO2 (ΦPSII/ΦCO2*) was constant in the wild-type leaves above 25°C and increased at lower temperatures (Fig. 3a). The anti-RbcS leaves had a higher ΦPSII/ΦCO2* than the wild type at all temperatures. The quantum requirement of photosynthesis in F. bidentis was sensitive to temperature, increasing more than 3-fold as temperature was reduced from 40°C to 10°C (Fig. 3a). The increase in the quantum requirement for CO2 fixation with declining leaf temperature is consistent with increased leakage (ϕ) of CO2 from the bundle sheath (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

a, The ratio of the quantum yields of PSII (ΦPSII) and gross CO2 assimilation (ΦCO2*) in wild-type (•) and anti-RbcS (141-1, ○) F. bidentis as a function of temperature. b, Modeled leakiness (ϕ) of CO2 from the bundle sheath, relativized to the estimated value for the wild type at the thermal optimum (35°C). Chlorophyll a fluorescence was measured in the 660- to 710-nm waveband, thereby reducing the contribution of PSI; ΦPSII was assessed using the technique of Genty et al. (1989). Gross assimilation was determined using the temperature correction for respiration described in Figure 1. Each value is the mean (± se) of measurements on three different leaves. Leakiness (ϕ) was determined from the relationship ΦPSII/ΦCO2* = 4 + 2.66m/(1 – ϕ), assuming equal contributions of linear and cyclic electron transport (e.g. m = 0.5) and that 43% of quanta are absorbed by PSII (Siebke et al., 1997). Leakiness values are shown relative to the wild-type value at the thermal optimum (35°C) because of the potential uncertainty surrounding the calculation of ϕ from fluorescence data. At 35°C, ϕ in the wild type was determined to be 0.39 ± 0.09 (n = 3).

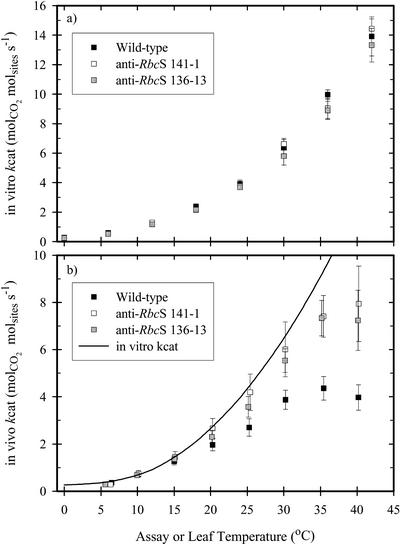

The in vitro kcat increased with increasing assay temperature, but there were no differences between the genotypes (Fig. 4a). Dividing the gross CO2 assimilation rate by the concentration of Rubisco catalytic sites yielded the in vivo kcat (Fig. 4b). At 15°C or lower, in vitro and in vivo kcat were the same in each genotype. Above 20°C, in vitro kcat exceeded the in vivo value in each genotype. The in vivo kcat in the anti-RbcS lines was greater than the wild-type value above 30°C (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

The temperature dependence of the in vitro (a), and in vivo (b)

kcat for Rubisco in wild-type (▪) and anti-RbcS (□,

) F. bidentis. Note the different scales on the two

panels. The in vitro data reflect the activity of the fully carbamylated

enzyme; in vivo kcat is estimated as gross photosynthesis divided by

the number of Rubisco catalytic sites. Each value represents the mean

(± se) of four measurements.

) F. bidentis. Note the different scales on the two

panels. The in vitro data reflect the activity of the fully carbamylated

enzyme; in vivo kcat is estimated as gross photosynthesis divided by

the number of Rubisco catalytic sites. Each value represents the mean

(± se) of four measurements.

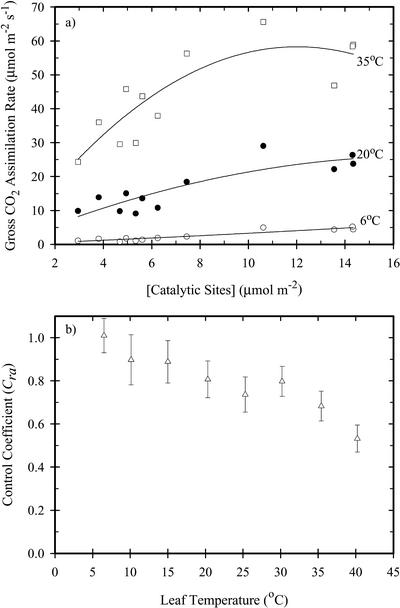

The Rubisco control coefficient (Cra) was determined from the relationship between gross photosynthesis and the concentration of Rubisco catalytic sites (Fig. 5a). At low-measurement temperatures, this relationship is linear, and a higher amount of Rubisco increased photosynthesis. At warmer temperatures, the relationship between photosynthesis and Rubisco content reached a plateau as other limitations became important. The control coefficient was inversely related to temperature, being about 0.68 at the thermal optimum and rising to 0.99 at the lowest measurement temperature; at 6°C, Cra was statistically equivalent to one (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

a, The relationship between gross photosynthesis and Rubisco catalytic site concentration at three temperatures; b, Rubisco Cra in F. bidentis as a function of leaf temperature. The error bars in b were determined from the se of the regression of photosynthesis on catalytic sites.

DISCUSSION

C4 plants are largely excluded from cool climates, probably because of poor photosynthetic performance at low temperatures relative to C3 species (Osmond et al., 1982). This poor performance may reflect an inherent biochemical limitation, and different steps of C4 photosynthesis have been suggested to be the rate-limiting factor at low temperatures. Using F. bidentis modified with antisense constructs to reduce Rubisco content, we determined the pattern of control exerted by Rubisco on C4 photosynthesis over the 6°C to 40°C temperature range. Although control is shared near the thermal optimum, Rubisco becomes a principle control over C4 photosynthesis at low temperatures. Several lines of evidence support this assertion. The in vitro activity of Rubisco matches the in vivo rate of gross photosynthesis at low temperatures, which indicates that the enzyme is the rate-limiting step. The apparent leakage of CO2 from the bundle sheath increases at low temperature in the wild type to an extent similar to the increase accompanying the reduction of Rubisco by antisense. Finally, the Rubisco Cra increases to near unity at low temperatures, which indicates almost complete control of C4 photosynthesis by Rubisco.

Rubisco Kinetics in Vitro and in Vivo

Between 6°C and 15°C, the kcat of Rubisco in vitro and the rate of gross photosynthesis in vivo are equivalent in wild-type F. bidentis. This indicates a strong Rubisco limitation of C4 photosynthesis at low temperatures. Reducing Rubisco content extends its control of C4 photosynthesis to higher temperatures, as shown by the wider thermal range across which the in vivo and the in vitro kcat values are equivalent in the anti-RbcS lines. The in vivo kcat was less than the in vitro kcat of Rubisco above 15°C in wild-type plants, and above 25°C in the anti-RbcS lines. A similar finding has been previously reported in the C4 grass B. gracilis (Pittermann and Sage, 2000). In B. gracilis populations from high elevation, the maximal in vitro Rubisco activity and net photosynthesis were equivalent below 22°C, whereas in plants from lower elevations, they were equivalent below 17°C. The high-elevation B. gracilis plants had 13% less Rubisco than low-elevation plants, which increased the temperature at which Rubisco activity became non-limiting.

At temperatures where Rubisco exerts high control, the activation energy (Ea) of gross assimilation (A*) should reflect the Ea of the enzyme. In F. bidentis, the situation is complicated by the increase in the Ea of Rubisco observed below 15°C. The Ea of A* between 5°C and 30°C was between the values for Rubisco above and below the break in the thermal response of the enzyme, as would be expected if the thermal response of the enzyme controls the thermal response of CO2 assimilation. The Ea of Rubisco from F. bidentis determined between 18°C to 42°C is similar to the 50 to 60 kJ mol–1 reported for a range of C4 species (Sage, 2002). A break in the thermal response of Rubisco has been previously noted in rice (Oryza sativa; Sage, 2002), and in both C3 and C4 species of Atriplex (Björkman and Pearcy, 1971). In wild-type F. bidentis, the Ea of PEPCase in vitro above 18°C is equivalent to that of photosynthesis. However, during the temperature response measurements, photosynthesis was operating on the plateau of the A/Ci curve (data not shown), above the low-CO2 region where PEPCase is postulated to control C4 photosynthesis (von Caemmerer and Furbank, 1999).

Leakage of CO2 from the Bundle Sheath

Reducing Rubisco capacity by antisense results in greater CO2 leakage (ϕ) than in wild-type F. bidentis across the 6°C to 40°C range, as indicated by the increase in ΦPSII/ΦCO2*. In C4 plants, the degree of overcycling, and hence CO2 ϕ, should increase if the ratio of the mesophyll to bundle sheath reaction rates increase (Henderson et al., 1992). As indicated by the similarity of the PEPCase activities in the three genotypes, the mesophyll reactions in the anti-RbcS leaves proceed at rates similar to those of the wild type. In this case, the CO2 concentration in the bundle sheath will increase, and ϕ will increase. Consistent with this, anti-RbcS F. bidentis shows increased carbon isotope discrimination at 25°C, relative to the wild type (von Caemmerer et al., 1997); in C4 plants, increased leakage of CO2 from the bundle sheath increases the discrimination against 13C (Farquhar, 1983). It is thus evident that the antisense plants are unable to reduce the rates of the mesophyll reactions to compensate for the reduced flow of carbon through Rubisco. Other explanations for the increase in ΦPSII/ΦCO2* at low temperatures cannot be completely excluded, but appear unlikely. Increases in the strength of alternative electron sinks, such as the Mehler reaction, should lead to increased ΦPSII/ΦCO2* (Krall and Edwards, 1991). However, the direct reduction of O2 likely accounts for less than 10% of total electron flux in C3 species, and there is no evidence of substantial rates in C4 plants (Badger et al., 2000). A mesophyll limitation of C4 photosynthesis, such as by PPDK, would reduce bundle sheath CO2 levels and hence reduce both ϕ and ΦPSII/ΦCO2*, at least until photorespiration begins to increase. Thus, although alternative explanations cannot be completely excluded, they are not consistent with the results presented here and in previous studies.

The quantum requirement of CO2 assimilation is constant above 15°C in a range of C4 dicots and monocots, indicating that the stoichiometry of the C4 and C3 cycles is unaltered at intermediate and warm temperatures (Oberhuber and Edwards, 1993). Similar results are reported here; ΦPSII/ΦCO2* is relatively constant in wild-type F. bidentis at temperatures where the control of photosynthesis is shared between Rubisco and other processes. In wild-type plants, the values of ΦPSII/ΦCO2* at warm temperatures (>25°C) shown here are similar to those reported by Siebke et al. (1997). As Rubisco becomes the principle control over the rate of photosynthesis at cooler temperatures (<20°C), bundle sheath leakiness increases, indicating overcycling of the CO2-concentrating reactions. In plants with reduced Rubisco, ϕ begins to increase at warmer temperatures than in wild-type leaves, as would be predicted from a higher Rubisco control of photosynthesis.

The Control of C4 Photosynthesis

The Cra defines the control exerted by Rubisco over the flow of carbon through the entire C4 photosynthetic pathway (Stitt, 1995). The high Cra below 20°C determined here shows that Rubisco dominates control at suboptimal temperatures, whereas the intermediate value at the thermal optimum shows that the control of photosynthetic carbon flux is shared between Rubisco and other processes. If several enzymes are colimiting, then reducing any one of them by antisense should result in a control coefficient close to one for that enzyme. This cannot be excluded here, although the agreement between the in vitro and in vivo kcat values of Rubisco would support the strong control exerted by this enzyme at lower temperatures. Theoretical models of C4 photosynthesis at the leaf level indicate conditions under which other biochemical processes may dominate the control of A, such as at low light or low CO2 (von Caemmerer and Furbank, 1999). At low PPFD, Rubisco control is not indicated, because the net CO2 assimilation rate of anti-RbcS F. bidentis is the same as that of a null-transformant control (Furbank et al., 1996; Siebke et al., 1997). Using Amaranthus edulis mutants with reduced PEPCase, Dever et al. (1997) have shown that PEPCase has a high Cra for C4 photosynthesis at low CO2, but this control is reduced when CO2 is saturating (Dever et al., 1997). For PPDK and NADP malate dehydrogenase, the control coefficients are 0.3 and 0, respectively, at 25°C (Furbank et al., 1997). Model predictions indicate that at or above the thermal optimum in air, C4 photosynthesis is limited by the regeneration of PEP or ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (von Caemmerer and Furbank, 1999), but our results indicate that Rubisco continues to exert significant control at or above the thermal optimum in F. bidentis.

Consequences for C4 Photosynthesis in Cool Climates

A limitation by Rubisco capacity on C4 photosynthesis at low temperature represents a mechanism to explain the relative rarity of the C4 syndrome in cool climate habitats. The carboxylation efficiency of Rubisco improves at low temperatures, because both the relative availability of CO2 versus O2 and the specificity of Rubisco for CO2 increase as temperature declines (Badger and Collatz, 1977; Berry and Raison, 1981). This improved efficiency is more advantageous to C3 species, because they typically have three to four times as much Rubisco as C4 plants (Ku et al., 1979; Long, 1999). Furthermore, the high partial pressure of CO2 in the bundle sheath ensures that little oxygenation occurs in C4 plants, so the improved efficiency of Rubisco at low temperatures will not directly affect C4 photosynthesis.

The minimal amount of Rubisco theoretically required for C4 plants to match C3 photosynthetic rates increases at lower temperatures (Long, 1999). Consistent with this, Rubisco accounts for only 4% to 8% of soluble leaf protein in the summer-active Death Valley native Tidestromia sp. but about 20% in cool-coastal Atriplex sp. (Osmond et al., 1982). Conversely, high-elevation ecotypes of B. gracilis contain less Rubisco than plants from low-elevation populations (Pittermann and Sage, 2000). Whereas C3 species frequently acclimate to low temperatures by increasing the amount of Rubisco (Treharne and Eagles, 1970; Holaday et al., 1992; Hurry et al., 1995), in C4 plants, the responses are more variable. In A. lentiformis, the Rubisco activity of plants grown at 23°C/18°C (day/night) is 60% greater than that of plants grown at 43°C/30°C (Pearcy, 1977), whereas Rubisco activity is insensitive to growth temperatures between 19°C and 31°C in maize (Zea mays; Ward, 1987) and between 14°C and 26°C in Muhlenbergia glomerata, a C4 grass native to boreal Canada (Kubien, 2003).

The Rubisco content of C4 species may be limited by the compartmentalization of the enzyme, because it is restricted to a reduced fraction of the leaf volume relative to C3 species (Dengler and Nelson, 1999). Increasing the content of Rubisco would likely require changes in the proportion and arrangement of mesophyll and bundle sheath tissues within the leaves of C4 plants or in the positioning of chloroplasts within the bundle sheath tissue. As a response to low temperatures this seems unlikely, because the spatial arrangement of these compartments influences the intercellular communication required for the efficient operation of the CO2-concentrating mechanism (Dengler and Nelson, 1999). In addition, the Rubisco to chlorophyll ratio is the same in C3 and C4 species if the amount of the enzyme in the C4 species is expressed on the basis of chlorophyll extracted from isolated bundle sheath cells (Ku et al., 1979; O. Ghannoum, personal communication). If this ratio is fixed, then C4 species could not match the Rubisco content of C3 plants, and the potential to increase the enzyme may be limited. Even if the bundle sheath cells could accommodate additional Rubisco, increasing the amount of the enzyme would have a negative effect on the nitrogen economy of C4 species, thus mitigating one of the ecological advantages maintained over C3 vegetation (Long, 1999; Pittermann and Sage, 2000). If this constraint exists, a potential solution would be to increase the kcat of the enzyme. Both kcat and Km for CO2 are higher in Rubisco from C4 species than from C3 plants (Seemann et al., 1984; Sage and Seemann, 1993; Sage, 2002). This increased turnover has not enabled C4 species to become common in cool climates.

In summary, we propose that C4 plants cannot contain sufficient Rubisco to match the photosynthetic rates of ecologically similar C3 species at low temperatures. A reduction in the amount of Rubisco by C4 species is possible because of the high CO2 concentration in the bundle sheath and is one of the fundamental advantages C4 plants have over their C3 competitors (Osmond et al., 1982). High control of C4 photosynthesis by Rubisco is a disadvantage at low temperatures and may be an inherent feature of the C4 pathway that precludes such species from becoming common in cool climates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth

Wild-type and anti-RbcS transgenic Flaveria bidentis were germinated in sand in a naturally lit greenhouse. The transgenic plants were T2 progeny of the 141-1 (one insert) and 136-13 (four inserts) primary transformants (Furbank et al., 1996). Four (wild type) or 7 (transgenic) weeks after germination, the seedlings were transplanted to 12-L pots containing 69% (v/v) Promix (Plant Products, Brampton, Canada), 17% (v/v) sand, and 17% (v/v) plant-compost. Plants were subsequently moved to a controlled environment chamber (GC-20, Enconair, Winnipeg, Canada) and maintained under a 16-h photoperiod with a maximal PPFD of 750 μmol m–2 s–1. The day/night temperature and relative humidity were 28°/20°C and 50%/75%, respectively. Plants were watered daily and fertilized weekly with 0.5× Hoagland solution supplemented with 3 mm NH4NO3.

Gas-Exchange Measurements

The photosynthetic responses to temperature and CO2 were measured with an open type leaf gas-exchange system using an infrared gas analyzer (Li-6262, Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE) to detect both CO2 and water vapor. In this system, mass flow controllers (model 840, Sierra Instruments, Monterey, CA) were used to supply N2, O2, and CO2 at the desired levels. All temperature and CO2 responses were measured at 200 ± 5 mbar O2. The air stream was humidified by passing the mixture through a water-filled flask which was set to a specific temperature in a water bath. For measurements at lower temperatures, the flask was placed on ice and filled with either water or a 70% (w/v) Suc solution. After humidification, CO2 was injected, and the flow of air was measured by a mass-flow transducer (831, Edwards, Wilmington, MA) before being passed through the temperature-controlled leaf cuvette and an infrared gas analyzer. Leaf temperature was measured by placing three fine wire (36-gauge) thermocouples in contact with the abaxial surface of the leaf. Illumination was provided by a cool-light source (KL-2500, Schott, Mainz, Germany). All gas exchange measurements were made on the youngest fully expanded leaf and were calculated according to von Caemmerer and Farquhar (1981).

Photosynthetic temperature responses were measured either at a constant PPFD of 1,500 μmol m–2 s–1 or at a temperature-dependent PPFD that was sufficient to saturate photosynthesis. These points were determined by evaluating the photosynthetic responses to light at 12°C, 22°C, and 32°C, using a portable photosynthesis system (Li-6400, Li-Cor). The y intercept of light response curve was taken as an estimate of Rd at each temperature. This approach was used to mitigate the potential for photoinhibition, particularly at the lower temperatures. Light intensity in the cuvette was measured using a photodiode (G1738, Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ) calibrated against a quantum sensor (Li-190s, Li-Cor). The temperature responses were measured at an ambient CO2 of 370 ± 2 μbar. The leaf to air vapor pressure deficit was maintained at 12 ± 2 mbar at temperatures greater than 10°C; at cooler temperatures, vapor pressure deficit was reduced. All temperature response measurements were initiated at 30°C; leaf temperature was subsequently increased in 5°C intervals to 40°C and then decreased to the lower temperatures. At each temperature, the leaf was allowed to equilibrate for a minimum of 15 min before measurement. After the last measurement was completed, the leaf was warmed to about 15°C, and two leaf discs (1.55 cm2 each) were rapidly removed and frozen in liquid N2. Leaf samples were stored at –80°C until enzymes were assayed.

Chlorophyll a Fluorescence Measurements

Chlorophyll a fluorescence was determined simultaneously with gas exchange during the temperature response measurements of the wild-type and 141-1 lines. We used a PAM-101 (Walz, Effeltrich, Germany) equipped with an emitter-detector unit (ED-101BL, Walz) that provides excitation light at 470 nm and detection in the 660- to 710-nm waveband. This enabled us to isolate the fluorescence signal originating from PSII (Pfündel, 1998). Each leaf was allowed to dark-adapt at 30°C for 30 min before the ratio of variable to maximal fluorescence (Fv/Fm) was assessed. Reaction center closure was achieved by applying a 0.8-s pulse of saturating light (approximately 4,000 μmol m–2 s–1). Once a leaf had reached steady state at a given temperature, the quantum yield of PSII (ΦPSII) was measured (Genty et al., 1989). Saturating pulses were applied at 90-s intervals; at each temperature, the average of three measurements was taken. There was no reduction in Fm′ with successive pulses. Thirty seconds after the last ΦPSII estimate was obtained, Fo′ was assessed by rapidly darkening the leaf in the presence of far-red light. Leaf absorbance was determined from the chlorophyll concentration (Siebke et al., 1997). Fluorescence nomenclature and calculations follow van Kooten and Snel (1990).

Enzyme and Chlorophyll Assays

The in vitro activities of Rubisco and PEPCase were assayed from 0°C to 42°C using leaf discs harvested from the leaves used for gas exchange analysis. Leaf samples (3.1 cm2) were rapidly ground (<90 s) at 0°C using a ten-broek glass-in-glass homogenizer containing 7 mL of extraction buffer (100 mm HEPES, pH 7.6, 2 mm Na-EDTA, 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm dithiothreitol [DTT], 9 mg mL–1 polyvinyl polypyrrolidone, 2 mg mL–1 bovine serum albumin, 2 mg mL–1 polyethylene glycol, 2.8% (v/v) Tween-80, 2 mm NaH2PO4, 11 mm amino-n-caproic acid, and 2.2 mm benzamide). Chlorophyll content was determined spectrophotometrically in N,N-dimethylformamide, using two aliquots of the crude extract (Porra et al., 1989).

Rubisco was quantified in aliquots of the crude extract, using a [14C]carboxy-arabinitol bisphosphate (CABP)-binding assay and assuming 6.5 binding sites per Rubisco (Butz and Sharkey, 1989). The CABP assay buffer consisted of 100 mm Bicine, 20 mm MgCl2, and 10 mm NaHCO3 at pH 8.2. The leaf extract (40 μL) was incubated in 40 μm 14CABP (specific activity, 27 Bq nmol–1) at room temperature for 15 min, followed by a 2.5-h incubation at 37°C in the presence of rabbit anti-Rubisco serum. The Rubisco-14CABP complexes were filtered with 0.45-μm Supor filters (Gelman, Ann Arbor, MI) and thoroughly washed with a 10 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.6, containing 10 mm MgCl2 and 150 mm NaCl). The radioactivity bound to the filters was measured by liquid scintillation spectroscopy.

A 3.33-mL aliquot of the crude leaf extract was added to 370 μL of a Rubisco activating solution (100 mm Bicine, pH 8.2) containing 280 mm MgCl2 and 200 mm NaHCO3, giving final concentrations of 28 mm MgCl2 and 20 mm NaHCO3, respectively (Sage and Seemann, 1993). This mixture was incubated at room temperature for 20 to 25 min to fully carbamylate Rubisco. The carbamylated extract was then kept on ice until being assayed. The remaining crude extract was kept on ice for subsequent determination of PEPCase activity.

Rubisco activity was assayed in a buffer containing 100 mm Bicine (pH 8.2), 1 mm Na-EDTA, 20 mm MgCl2, 5 mm DTT, 1 unit mL–1 ribulose-5-P kinase, 1.7 unit mL–1 phospho-ribulo-isomerase, 2 mm ATP, 2 mm Rib-5-P, and 12 mm NaH14CO3 (specific activity, 27 Bq nmol–1, ICN Pharmaceuticals, Costa Mesa, CA; Pittermann and Sage, 2000). The assay buffer (400 μL) was allowed to equilibrate at a given temperature for 90 s, after which the assay commenced with the addition of 100 μL of the carbamylated extract. Assays ran for 30 to 60 s and were terminated by the addition of 500 μL of 2 n HCl. The radioactivity of acid-stable products was measured by liquid scintillation spectroscopy. Rubisco kcat (mol CO2 fixed [mol active sites]–1 s–1) was determined from the in vitro activity and the concentration of catalytic sites.

PEPCase activity was assayed in a buffer containing 50 mm Bicine (pH 8.2), 1 mm Na-EDTA, 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm DTT, 4.6 mm PEP, and 4.6 mM G-6-P, 0.2 mm NADH, 0.3 unit mL–1 MDH, and 5.4 mm NaH14CO3 (Pittermann and Sage, 2000). Assays were initiated by the addition of 20 μL of the crude extract to 480 μL of the assay buffer, and terminated by the addition of 500 μL of 2 n HCl. Acid stable radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectroscopy.

Cra

A flux control coefficient (Cra) was calculated to determine the extent to which Rubisco controls C4 photosynthesis across the range of measurement temperatures (Kacser and Burns, 1973; Stitt, 1995). The coefficient was defined as:

|

(1) |

where A* is the gross CO2 assimilation rate (A + Rd, where Rd is respiration) and [E] is the concentration of Rubisco catalytic sites. To obtain the relationship between photosynthesis and Rubisco content, we regressed gross CO2 assimilation against catalytic site concentration, using the data from the temperature response measurements. We made no underlying assumptions regarding the shape of this relationship and simply used the curve that gave the best fit at each temperature. The derivatives of each curve were then taken at each wild-type catalytic site concentration to determine δA*/δ[E] between 6°C and 40°C. A second-order polynomial was fit to the respiration rates, determined during the light response measurements, to provide an estimate of respiration at each temperature.

Acknowledgments

We thank George Espie (University of Toronto) for the use of the PAM-101. Katharina Siebke and Oula Ghannoum (Australian National University) and Prof. Steve Tonsor (University of Pittsburgh) provided helpful comments and interesting discussion.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.103.021246.

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (grant no. OGP0154273 to R.F.S.).

References

- Badger MR, Collatz GJ (1977) Studies on the kinetic mechanism of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase and oxygenase reactions, with particular reference to the effect of temperature on kinetic parameters. Carnegie Inst Wash Year Book 76: 355–361 [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, von Caemmerer S, Ruuska S, Nakano H (2000) Electron flow to oxygen in higher plants and algae: rates and control of direct photoreduction (Mehler reaction) and Rubisco oxygenase. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B 355: 1433–1446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JA, Raison JK (1981) Responses of macrophytes to temperature. In OL Lange, PS Nobel, CB Osmond, H Ziegler, eds, Physiological Plant Ecology, Vol 12A. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp 277–338 [Google Scholar]

- Björkman O, Pearcy RW (1971) Effect of growth temperature on the temperature dependence of photosynthesis in vivo and on the CO2 fixation by carboxydismutase in vitro in C3 and C4 species. Carnegie Inst Wash Year Book 70: 511–520 [Google Scholar]

- Butz ND, Sharkey TD (1989) Activity ratios of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase accurately reflect carbamylation ratios. Plant Physiol 89: 735–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitty JA, Furbank RT, Marshall JS, Chen Z, Taylor WC (1994) Genetic transformation of the C4 plant Flaveria bidentis. Plant J 6: 949–956 [Google Scholar]

- Dengler NC, Nelson T (1999) Leaf structure and development in C4 plants. In RF Sage, RK Monson, eds, C4 Plant Biology. Academic Press, Toronto, pp 133–172

- Dever LV, Bailey KJ, Leegood LC, Lea PJ (1997) Control of photosynthesis in Amaranthus edulis mutants with reduced amounts of PEP carboxylase. Aust J Plant Physiol 24: 469–476 [Google Scholar]

- Edwards GE, Nakamoto H, Burnell JN, Hatch MD (1985) Pyruvate, Pidikinase and NADP-malate dehydrogenase in C4 photosynthesis: properties and mechanism of light/dark regulation. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 36: 255–286 [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer JR (1978) Implications of quantum yield differences on the distributions of C3 and C4 grasses. Oecologia 31: 255–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer JR, Björkman O (1977) Quantum yields for CO2 uptake in C3 and C4 plants. Plant Physiol 59: 86–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD (1983) On the nature of carbon isotope discrimination in C4 species. Aust J Plant Physiol 10: 205–226 [Google Scholar]

- Furbank RT, Chitty JA, Jenkins CLD, Taylor WC, Trevanion SJ, von Caemmerer S, Ashton AR (1997) Genetic manipulation of key photosynthetic enzymes in the C4 plant Flaveria bidentis. Aust J Plant Physiol 24: 477–485 [Google Scholar]

- Furbank RT, Chitty JA, von Caemmerer S, Jenkins CLD (1996) Antisense RNA inhibition of RbcS gene expression reduces Rubisco level and photosynthesis in the C4 plant Flaveria bidentis. Plant Physiol 111: 725–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genty B, Briantais J-M, Baker NR (1989) The relationship between the quantum yield of photosynthetic electron transport and quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochim Biophys Acta 990: 87–92 [Google Scholar]

- Henderson SA, von Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD (1992) Short-term measurements of carbon isotope discrimination in several C4 species. Aust J Plant Physiol 19: 263–285 [Google Scholar]

- Holaday AS, Martindale W, Alred R, Brooks AL, Leegood RC (1992) Changes in activities of enzymes of carbon metabolism in leaves during exposure of plants to low temperature. Plant Physiol 98: 1105–1114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurry V, Keerberg O, Pärnik T, Gardeström P, Öquist G (1995) Cold-hardening results in increased activity of enzymes involved in carbon metabolism in leaves of winter rye (Secale cereale L.). Planta 195: 554–562 [Google Scholar]

- Kacser H, Burns JA (1973) The control of flux. Symp Soc Exp Biol 27: 65–104 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krall JP, Edwards GE (1991) Environmental effects on the relationship between the quantum yields of carbon assimilation and in vivo PSII electron transport in maize. Aust J Plant Physiol 18: 267–278 [Google Scholar]

- Krall JP, Edwards GE (1993) PEP carboxylases from two C4 species of Panicum with markedly different susceptibilities to cold inactivation. Plant Cell Physiol 34: 1–11 [Google Scholar]

- Ku MSB, Schmitt MR, Edwards GE (1979) Quantitative determination of RuBP carboxylase-oxygenase protein in leaves of several C3 and C4 plants. J Exp Bot 30: 89–98 [Google Scholar]

- Kubien DS (2003) On the performance of C4 photosynthesis at low temperatures and its relationship to the ecology of C4 plants in cool climates. PhD thesis. University of Toronto

- Leegood RC, Edwards GE (1996) Carbon metabolism and photorespiration: temperature dependence in relation to other environmental factors. In NR Baker, ed, Photosynthesis and the Environment. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 191–221

- Long SP (1983) C4 Photosynthesis at low temperatures. Plant Cell Environ 6: 345–363 [Google Scholar]

- Long SP (1999) Environmental responses. In RF Sage, RK Monson, eds, C4 Plant Biology. Academic Press, Toronto, pp 215–249

- Matsuba K, Imaizumi N, Kaneko S, Samejima M, Ohsugi R (1997) Photosynthetic responses to temperature of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase type C4 species differing in cold sensitivity. Plant Cell Environ 20: 268–274 [Google Scholar]

- Oberhuber W, Edwards GE (1993) Temperature dependence of the linkage of quantum yield of photosystem II to CO2 fixation C4 and C3 plants. Plant Physiol 101: 507–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmond CB, Winter K, Ziegler H (1982) Functional significance of different pathways of CO2 fixation in photosynthesis. In OL Lange, PS Nobel, CB Osmond, H Ziegler, eds, Physiological Plant Ecology II. Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology, Vol 12B. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp 480–547 [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy RW (1977) Acclimation of photosynthetic and respiratory carbon dioxide exchange to growth temperature in Atriplex lentiformis (Torr.) Wats. Plant Physiol 59: 795–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfündel E (1998) Estimating the contribution of photosystem I to total leaf chlorophyll fluorescence. Photosynth Res 56: 185–195 [Google Scholar]

- Pittermann J, Sage RF (2000) Photosynthetic performance at low temperature of Bouteloua gracilis Lag., a high-altitude C4 grass from the Rocky Mountains, USA. Plant Cell Environ 23: 811–823 [Google Scholar]

- Pittermann J, Sage RF (2001) The response of the high altitude C4 grass Muhlenbergia montana (Nutt.) A.S. Hitchc. to long- and short-term chilling. J Exp Bot 52: 829–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porra RJ, Thompson WA, Kriedemann PE (1989) Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents, verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta 975: 384–394 [Google Scholar]

- Rundel PW (1980) The ecological distribution of C4 and C3 grasses in the Hawaiian Islands. Oecologia 45: 354–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF (2002) Variation in the kcat of Rubisco in C3 and C4 plants and some implications for photosynthetic performance at high and low temperature. J Exp Bot 53: 609–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Seemann JR (1993) Regulation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase activity in response to reduced light intensity in C4 plants. Plant Physiol 102: 21–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Wedin DA, Li M (1999) The biogeography of C4 photosynthesis, patterns and controlling factors. In RF Sage, RK Monson, eds, C4 Plant Biology. Academic Press, Toronto, pp 313–373

- Seemann JR, Badger MR, Berry JA (1984) Variations in the specific activity of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase between species utilizing different photosynthetic pathways. Plant Physiol 74: 791–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebke K, von Caemmerer S, Badger M, Furbank RT (1997) Expressing an RbcS antisense gene in transgenic Flaveria bidentis leads to an increased quantum requirement for CO2 fixed in photosystems I and II. Plant Physiol 115: 1163–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M (1995) The use of transgenic plants to study the regulation of plant carbohydrate metabolism. Aust J Plant Physiol 22: 635–646 [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Schulze D (1994) Does Rubisco control the rate of photosynthesis and plant growth? an exercise in molecular ecophysiology. Plant Cell Environ 17: 465–487 [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T, Boku K (1976) Differing sensitivity of pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase to low temperature in maize cultivars. Plant Cell Physiol 17: 851–854 [Google Scholar]

- Teeri JA, Stowe LG (1976) Climatic patterns and the distribution of C4 grasses in North America. Oecologia 23: 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tieszen LL, Senyimba MM, Imbamba SK, Troughton JH (1979) The distribution of C3 and C4 grasses and carbon isotope discrimination along an altitudinal and moisture gradient in Kenya. Oecologia 37: 337–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treharne KJ, Eagles CF (1970) Effect of temperature on photosynthetic activity of climatic races of Dactylis glomerata L. Photosynthetica 4: 107–117 [Google Scholar]

- van Kooten O, Snel JFH (1990) The use of chlorophyll fluorescence nomenclature in plant stress physiology. Photosynth Res 25: 147–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD (1981) Some relationships between the biochemistry of photosynthesis and the gas-exchange of leaves. Planta 153: 376–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Furbank RT (1999) Modelling C4 photosynthesis. In RF Sage, RK Monson, eds, C4 Plant Biology. Academic Press, Toronto, pp 173–211

- von Caemmerer S, Millgate A, Farquhar GD, Furbank RT (1997) Reduction of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase by antisense RNA in the C4 plant Flaveria bidentis leads to reduced assimilation rates and increased carbon isotope discrimination. Plant Physiol 113: 469–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward DA (1987) The temperature acclimation of photosynthetic responses to CO2 in Zea mays and its relationship to the activities of photosynthetic enzymes and the CO2-concentrating mechanism of CO2 photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ 10: 407–411 [Google Scholar]