Abstract

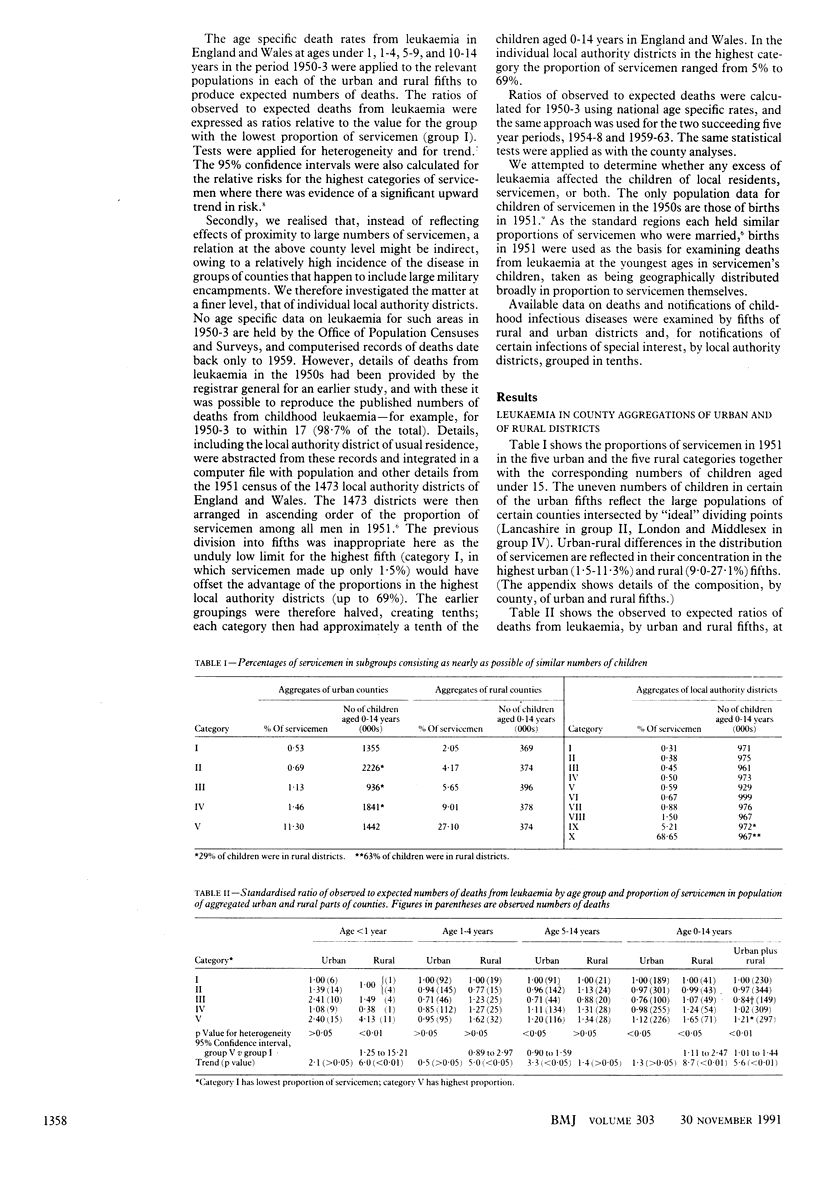

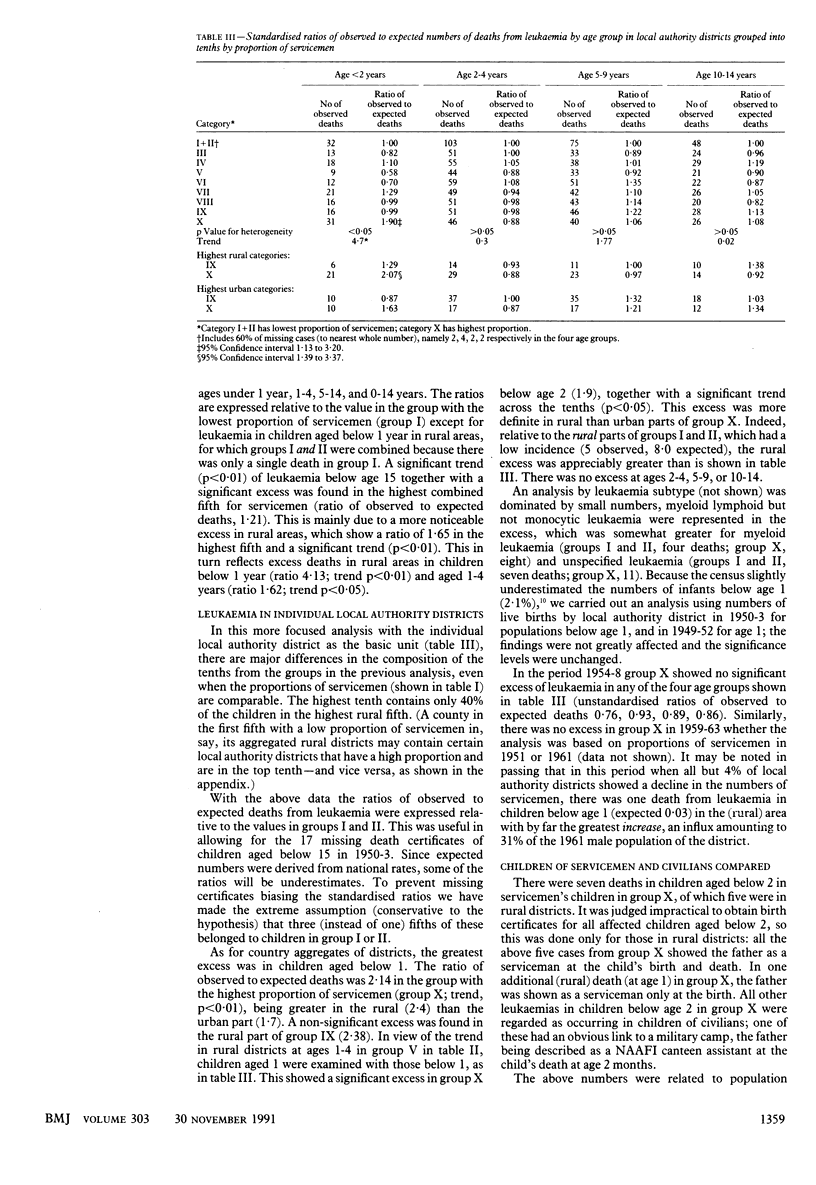

OBJECTIVE--To determine if any excess of childhood leukaemia was associated with the large and increasing numbers of national military servicemen in 1949 and 1950, particularly in rural districts. This would be a further test of the hypothesis that childhood leukaemia can originate in an infection, the transmission of which is facilitated by an increased number of unaccustomed contacts in the community. DESIGN--Rural and urban districts, aggregated by county, were ranked by proportion of servicemen, and five groups containing similar numbers of children were created. In addition, individual local authority districts were ranked and grouped in tenths. Mortality from childhood leukaemia 1950-3 was examined in these groups. Data on infectious diseases were also examined, as well as data on leukaemia in later periods. SETTING--England and Wales. SUBJECTS--Children aged under 15 years. RESULTS--In 1950-3 but not subsequently a significant excess of leukaemia in children under 15 was found in the fifth of county groupings with the highest proportions of servicemen. This was due mainly to a significant excess in children under 2 years (and especially in those under 1 year) in rural districts. It was confirmed among the tenth of local authority districts with the highest proportion of servicemen. These rural areas showed significantly more notifications of, and deaths from, poliomyelitis among children than the rural average. CONCLUSIONS--The findings support the infection hypothesis. That the excess of leukaemia was greatest in children under 1 year suggests transmission of infection among adults and thence to the fetus. The pattern of spread of poliomyelitis may also have been influenced by the presence of large numbers of servicemen.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson R. M., May R. M. Directly transmitted infections diseases: control by vaccination. Science. 1982 Feb 26;215(4536):1053–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.7063839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves M. F. Speculations on the cause of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 1988 Feb;2(2):120–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlen L. J., Clarke K., Hudson C. Evidence from population mixing in British New Towns 1946-85 of an infective basis for childhood leukaemia. Lancet. 1990 Sep 8;336(8715):577–582. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93389-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlen L. J., Hudson C. M., Stiller C. A. Contacts between adults as evidence for an infective origin of childhood leukaemia: an explanation for the excess near nuclear establishments in west Berkshire? Br J Cancer. 1991 Sep;64(3):549–554. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlen L. Evidence for an infective cause of childhood leukaemia: comparison of a Scottish new town with nuclear reprocessing sites in Britain. Lancet. 1988 Dec 10;2(8624):1323–1327. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90867-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robison L. L., Buckley J. D., Daigle A. E., Wells R., Benjamin D., Arthur D. C., Hammond G. D. Maternal drug use and risk of childhood nonlymphoblastic leukemia among offspring. An epidemiologic investigation implicating marijuana (a report from the Childrens Cancer Study Group). Cancer. 1989 May 15;63(10):1904–1911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]