Abstract

The potential of a dendritic cell (DC)-based vaccine against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection in humans was explored with SCID mice reconstituted with human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). HIV-1-negative normal human PBMC were transplanted directly into the spleens of SCID mice (hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice) together with autologous mature DCs pulsed with either inactivated HIV-1 (strain R5 or X4) or ovalbumin (OVA), followed by a booster injection 5 days later with autologous DCs pulsed with the same respective antigens. Five days later, these mice were challenged intraperitoneally with R5 HIV-1JR-CSF. Analysis of infection at 7 days postinfection showed that the DC-HIV-1-immunized hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice, irrespective of the HIV-1 isolate used for immunization, were protected against HIV-1 infection. In contrast, none of the DC-OVA-immunized mice were protected. Sera from the DC-HIV-1- but not the DC-OVA-immunized mice inhibited the in vitro infection of activated PBMC and macrophages with R5, but not X4, HIV-1. Upon restimulation with HIV-1 in vitro, the human CD4+ T cells derived from the DC-HIV-1-immunized mice produced a similar R5 HIV-1 suppressor factor. Neutralizing antibodies against human RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, alpha interferon (IFN-α), IFN-β, IFN-γ, interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-10, IL-13, IL-16, MCP-1, MCP-3, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), or TNF-β failed to reverse the HIV-1-suppressive activity. These results show that inactivated HIV-1-pulsed autologous DCs can stimulate splenic resident human CD4+ T cells in hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice to produce a yet-to-be-defined, novel soluble factor(s) with protective properties against R5 HIV-1 infection.

Mice with a genetically inherited severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID mice) develop a surrogate human immune system when injected with human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). These mice, termed hu-PBL-SCID mice, have served as a valuable model for the study of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) pathogenesis (18, 22). It has been shown that the human T cells transplanted into SCID mice are activated (26) and proliferate in response to nominal antigens presented by antigen-presenting cells (APC) of murine origin (34). Thus, experiments have been conducted to induce and study human immune responses in hu-PBL-SCID mice (1, 3, 7, 17). There are, however, two major limitations to the development of strong human immune responses in these hu-PBL-SCID mice. The first is the lack of appropriate human APC, including dendritic cells (DC), while the second is the lack of a suitable microenvironment, such as the presence of normal lymphoid organs and architecture (34). Each of these issues is known to facilitate primary interaction between T cells and APC. To overcome the lack of APC, Delhem et al. (4) have used autologous skin transplants containing tissue DC as a source of APC and have succeeded in demonstrating the induction of primary major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-restricted human T-cell responses against HIV-1 envelope in hu-PBL-SCID mice. Furthermore, Santini et al. (28) have recently reported that HIV-1-pulsed, monocyte-derived human mature DC can stimulate primary human anti-HIV-1 antibody production in the SCID mouse system.

It is reasoned that since hu-PBL-SCID mice are permissive for R5 HIV-1 (23), this animal model should provide us with valuable information for the evaluation of candidate vaccines against HIV-1. Despite the success that has been achieved in the induction of human T- and B-cell immune responses against HIV-1, such HIV-1-immunized hu-PBL-SCID mice have not to date been utilized for the evaluation of protective immunity against HIV-1. In the present study, we found that transfer of human PBMC, together with inactivated HIV-1-pulsed autologous DC, directly into the mouse spleen elicited a protective immune factor against R5 HIV-1 infection. The factor was synthesized predominantly by human CD4+ T cells in response to HIV-1 antigen and appears to be unrelated to the presently identified R5 HIV-1 suppressive cytokines and chemokines. The data presented here not only document the establishment of a novel model to study candidate DC-based vaccines against HIV-1 but also provide data to support the existence of a unique factor with R5 HIV-1-suppressive properties that can be potentially exploited as an adjunct to therapy against HIV-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

The SCID mice utilized (C.B-17-scid) were purchased from Crea Japan (Kanagawa, Japan). SCID mice lacking natural killer (NK) cells, i.e., NOD/Shi-scid γc−/− (8) and BALB/c-rag2−/− γc−/− mice (24), were also used in the present study. The mice were kept in the specific-pathogen-free and P3 animal facilities of the Laboratory Animal Center, University of the Ryukyus. The protocols for the care and use of hu-PBL-SCID mice were approved by the committee on animal research of the University of the Ryukyus prior to initiation of the study. The NK cell lineages in the C.B-17-scid mice were depleted by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 1 mg of rat anti-mouse interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor β (clone TMβ-1) (33) per animal.

Reagents.

The media used were RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml (hereafter called RPMI medium) and Iscove's medium (Lifetechnologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum with the same antibiotics (hereafter called Iscove's medium). Soluble recombinant human IL-4 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) were generated from COS cell cultures transfected with the appropriate genes in the expression plasmid DNAs pCMhIL4 and pCMhGM (RIKEN Gene Bank, Ibaraki, Japan), respectively, by the Fugene 6 method (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, Ind.). The concentrations of human IL-4 and GM-CSF were determined by using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (BioSource, Camarillo, Calif.). Human recombinant IL-2 and M-CSF were purchased from Shionogi (Osaka, Japan) and Pepro Tech EC Ltd. (London, United Kingdom), respectively.

The anti-human MIP-1α, anti-human MIP-1β, anti-human IL-4, anti-human IL-10, anti-human IL-12, anti-human IL-13, anti-human IL-16, anti-human MCP-1, and anti-human MCP-3 monoclonal antibodies (MAb) were all purchased from R&D Systems (Rockville, Md.). Goat anti-human alpha interferon (IFN-α) and IFN-β were purchased from Pepro Tech. To maintain their neutralizing activity, these antibodies in lyophilized form were reconstituted in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, and aliquots were kept at −80°C until use.

Virus.

HIV-1JR-CSF and HIV-1JR-FL (9) and HIV-1NL4-3 (2) viral stocks were each produced in the 293T cell line by transfection with the appropriate HIV-1 infectious plasmid DNA, utilizing the calcium phosphate method (31). HIV-1SF162 (30) was produced in phytohemagglutinin-stimulated PBMC. HIV-1IIIB was harvested from Molt-4/IIIB cell cultures. The 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) was determined by an end point infectious assay with phytohemagglutinin-activated PBMC. For immunization with HIV-1, the viral stocks were prepared in autologous PBMC cultures activated with immobilized anti-CD3 MAb. These HIV-1 preparations were inactivated with aldrithiol-2 (AT-2), as previously described by Rossio et al. (27). AT-2 was removed by three successive ultrafiltration in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), using 100-kDa-cutoff centrifugal filtration devices (Centriprep 100; Amicon, Beverly, Mass.).

Generation of monocyte-derived DC.

Fresh PBMC at 3 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI medium were dispensed into individual wells of 12-well plates (1 ml/well) which had been previously coated with autologous plasma for 30 min at 37°C. The PBMC cultures were allowed to incubate at 37°C for 1 h. After gentle washing with serum-free RPMI 1640 medium, the adherent cells were cultured in Iscove's modification of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (2 ml/well) containing human GM-CSF (500 ng/ml) and IL-4 (200 ng/ml) for 5 days. The resulting immature DC cultures were depleted of contaminating lymphocytes by using a monocyte negative isolation kit (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) and were further cultured with human IFN-β (1,000 U/ml; Toray, Tokyo, Japan) for 1 day to obtain mature DC, essentially as described by Santini et al. (28).

Transplantation, immunization, and infection.

Groups of SCID mice received mature DC (5 × 105 cells) which were pulsed for 2 h at 37°C with either AT-2-inactivated HIV-1 (40 ng of p24) or 100 μg of ovalbumin (OVA) in 100 μl of RPMI medium. These DC were mixed with autologous fresh PBMC (3 × 106 cells) in a final volume of 100 μl and then were directly injected into the spleens of SCID mice. Five days later, the same number of DC pulsed with antigen were inoculated into the spleen or peritoneal cavity. Five days later, some mice in each group were sacrificed, blood was collected by cardiocentesis, and human lymphocytes were recovered from the peritoneal cavity by lavage and from the spleen. The remaining mice in each group were challenged i.p. with 1,000 TCID50 of HIV-1JR-CSF (100 μl/animal). After 7 days, the mice were sacrificed, their blood was obtained, and human lymphocytes were collected from the peritoneal cavity by lavage and from the spleen. The peritoneal lavage fluids, sera, and lymphocyte culture supernatants were examined for levels of HIV-1 p24 with an ELISA kit (Zepto Metrix, Buffalo, N.Y.). Fresh lymphocytes were examined for proviral DNA by a quantitative PCR assay (10). Target cells used for in vitro infection assays consisted of normal PBMC activated with magnetic beads conjugated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 MAb (Dynal) at a cell-to-bead ratio of 1:1 in RPMI medium containing 20 U of human IL-2 per ml for 3 days. Some experiments utilized cultured macrophages derived from normal human PBMC, which were prepared by culturing adherent PBMC with 20 ng of human M-CSF per ml for 5 to 7 days. These activated PBMC or cultured macrophages (5 × 105 cells) were preincubated in 50 μl of medium, diluted serum, and culture supernatant samples at 37°C for 1 h in 96-well U-bottom microtiter plates (BD PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.). Subsequently, 50 μl of the HIV-1 stock containing 500 TCID50 of HIV-1 was added to each well. After incubation at 37°C for 3 h, the cells were washed three times and cultured in 200 μl of RPMI medium containing 20 U of IL-2 per ml for 3 to 5 days. HIV-1 replication was monitored by the quantitation of HIV-1 p24 produced in the culture supernatants. In order to determine whether the inhibitor of HIV-1 replication present in the immune sera or culture supernatant fluids consisted of known cytokines, a number of anti-human cytokine neutralizing antibodies at 10 μg/ml were preincubated with the sera or restimulated culture supernatants on ice for 30 min and then analyzed with the infection assay described above. Among the human cytokines tested with the present infection assay, while pretreatment of cultured human macrophages with IL-10, IL-16, IFN-α, IFN-β, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), or TNF-β at 50 ng/ml completely inhibited the infection with R5 HIV-1JR-CSF, IL-4, MCP-1, and MCP-3 showed marginal inhibitory effects. We confirmed the biological role of the appropriate inhibitory cytokines with the use of neutralizing antibodies against the respective cytokines, which were shown to completely reverse their HIV-1 inhibition activity at 10 μg/ml (data not shown).

in vitro restimulation.

For the measurement of antigen-specific human cellular immune responses, lymphoid cells (2 × 106 cells) collected from the spleens and peritoneal lavage of the immunized mice were cultured for 2 days at 37°C with 2 × 105 autologous APC (adherent PBMC) in the presence or absence of either 1 μg of OVA or AT-2-inactivated HIV-1 containing 40 ng of p24 in a volume of 1 ml in individual wells of a 24-well plate (BD PharMingen). The medium consisted of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 20 U of human IL-2 per ml. The concentration of human IFN-γ produced in the culture supernatants was determined with commercial ELISA kits (R&D Systems). Unfractionated or enriched populations of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells purified by the magnetic bead-positive selection method (Dynal) were cultured in 12-well plates (BD PharMingen) in the presence of APC and antigen, as outlined above, for preparation of the HIV-1 suppressive factor and for identification of the potential cell lineage that synthesized such a factor. The purity of the isolated CD4 and CD8 single-positive cells was always > 95% as determined by flow cytometric analysis. Contamination of human B cells within these T-cell fractions was not detected by staining with anti-CD20 MAb (data not shown).

Assay for human cytokines and antibodies.

Commercial kits for human TNF-α, IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IL-16, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, MCP-1, and MCP-3 (BioSource) TGF-β (R&D Systems), and IFN-β (Fuji Rebio Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were employed. All assays were performed in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, and cytokine levels were calculated from values obtained by using standard curves determined with recombinant cytokines. For select experiments depletion of human β-chemokines was achieved with heparin-Sepharose (Pharmacia, Tokyo, Japan). Bound materials were eluted from the column in PBS containing 2 M NaCl. For the measurement of OVA-specific human antibodies, serial dilutions of the serum samples to be tested were added to 96-well ELISA microtiter plates (Nunc, Rochester, N.Y.) which were precoated with 10 μg of OVA per ml at 37°C for 2 h. The bound human antibody was developed with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human immunoglobulin G (IgG) (American Qualex, San Clemente, Calif.), followed by incubation in a buffer containing tetramethyl benzidine (Sigma) and hydrogen peroxide (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Inc., Osaka, Japan). HIV-1 specific human antibodies were detected by Western blot assay with LAV Blot1 (Fuji Rebio Co.).

Flow cytometry.

Cell samples were incubated with 0.1 mg of normal human IgG per ml in fluorescence-activated cell sorter buffer (PBS containing 2% fetal calf serum and 0.1% sodium azide) on ice for 15 min and then were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate- or Cy5-labeled anti-CCR5 (T227) (32), phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CXCR4 (12G5; BD PharMingen), phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CD4 (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, Calif.), or Cy5-labeled OKT-4 on ice for 30 min. The cells were washed three times in fluorescence-activated cell sorter buffer and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Cells were analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer, using Cell Quest software (BD PharMingen). Isotype-matched MAb were utilized as controls to stain an aliquot of the cells to be analyzed for purposes of establishing gates and for determination of the frequency of positively stained cells.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed by Student's t test with the Stat View-J 4.02 statistics program (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, Calif.).

RESULTS

Induction of human immune responses in SCID mice.

For the preparation of hu-PBL-SCID mice, SCID mice previously have generally been engrafted with 2 ×107 fresh human PBMC by i.p. injection. In the studies presented here, we have attempted an intrasplenic (i.s.) transfer of human PBMC and found that this method was superior to the one previously used with regard to both a more efficient engraftment of the human T cells and reduction of mouse death caused by severe graft-versus-host disease (data not shown). By using this i.s. transfer method, the number of PBMC required for initial inoculation could be reduced by approximately 1 log unit for generation of more than 5 × 106 human CD3+ T cells within 2 weeks (data not shown). In addition, these mice (hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice) produced higher levels of human Ig than those generated by the i.p. transfer. These findings indicate that human T and B lymphocytes directly inoculated into the mouse spleen are more efficiently activated than those inoculated into the peritoneal cavity.

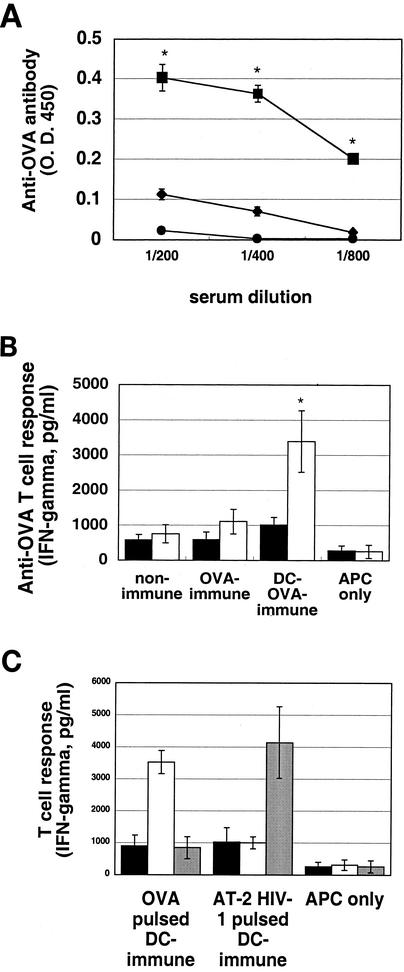

Preliminary studies were carried out to determine the requirements for the generation of antigen-specific human immune responses in these hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice. Subcutaneous immunization of these mice with OVA incorporated into Freund's adjuvant failed to induce detectable anti-OVA-specific human immune responses (data not shown). In the second series of studies, we attempted to immunize the mice with antigen-pulsed autologous mature DC generated from peripheral blood monocytes. Fresh PBMC (3 × 106 cells) from normal human donors were transferred into the SCID mouse spleen together with autologous mature DC (5 × 105 cells) pulsed with OVA (100 μg) or AT-2-inactivated HIV-1JR-CSF (containing 40 ng of p24). All of the HIV-1 stocks used were prepared in autologous PBMC cultures in order to avoid contamination with allogeneic antigens. On day 5, the mice received an i.s. booster injection with similarly prepared antigen-pulsed DC (5 × 105 cells/animal). After 5 days, the mice were examined for antigen-specific human immune responses (Fig. 1). Sera from the DC-OVA-immunized mice showed a significant human anti-OVA antibody titer (Fig. 1A), and the lymphoid cells from these mice responded to OVA by producing human IFN-γ upon stimulation with OVA-pulsed APC in vitro (Fig. 1B). Importantly, while the DC-HIV-1-immunized mice showed human anti-HIV-1 cellular immune responses (Fig. 1C), the sera from these mice showed very low or no detectable antibody against HIV-1 as determined by Western blot analysis (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Induction of antigen-specific human immune responses in hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice by immunization with antigen-pulsed DC. (A) PBMC (3 × 106 cells) alone (nonimmune) (•), with OVA (100 μg) (OVA immune) (⧫), or with DC (5 × 105 cells) pulsed with OVA (100 μg) (DC-OVA immune) (▪) were engrafted into the spleens of SCID mice. Five days later, the PBMC-OVA-immunized mice received a booster injection with OVA and the DC-OVA-immunized mice received a booster injection with DC-OVA. Five days later, serum samples were collected and human anti-OVA antibodies were measured by ELISA. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from six independent experiments. *, P < 0.05. (B) Lymphocytes (2 × 106 cells) recovered from hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice were cocultured with 2 × 105 autologous APC (adherent PBMC) in the presence (open bars) or absence (solid bars) of 1 μg of OVA per ml at37°C for 2 days in 1 ml of RPMI medium containing 20 U of human IL-2 per ml. APC cultured alone served as controls. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from six independent experiments. *, P < 0.05. (C) Lymphocytes (2 × 106 cells) recovered from hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice which were immunized with either DC-OVA or DC-AT-2-inactivated HIV-1JR-CSF were either not restimulated (solid bars) or restimulated as outlined for panel B in the presence of OVA (open bars) or AT-2-inactivated HIV-1 (containing 40 ng of p24) (shaded bars), respectively, for 2 days. Supernatant fluids from such cultures were harvested, and the levels of human IFN-γ were determined by ELISA. All results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from six independent experiments. *, P < 0.05.

Protection against HIV-1 challenge in vivo.

In order to examine whether the induced anti-HIV-1 immune responses are protective, these DC-OVA- and DC-HIV-1-immunized hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice were challenged i.p. with infectious R5 HIV-1JR-CSF. After 7 days postchallenge, these mice were examined for HIV-1 infection by assaying for provirus in the lymphocytes and levels of p24 in the serum or supernatant fluid of the lymphocyte cultures. As shown in Table 1, all of the mice immunized with DC-OVA were HIV-1 infected. Surprisingly, the mice immunized with DC-HIV-1JR-CSF were completely protected against HIV-1 infection. Furthermore, the mice immunized with the inactivated X4 isolate of HIV-1NL4-3 were also protected against the R5 HIV-1 infection. Similar results were obtained in three other experiments using hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice reconstituted with PBMC from two other donors (Table 1 and data not shown). Based on these results, we reasoned that the protection of the mice against the R5 HIV-1 infection might be mediated by the CCR5-binding human β-chemokines MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and/or RANTES. However, this possibility was found to be unlikely, since the human β-chemokine levels in the immune sera were lower than those required for suppression of the R5 HIV-1 infection in vitro, and the sera from the DC-OVA-immunized mice also contained similar levels of these β-chemokines (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Protection of hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice against HIV-1 infection by immunization with HIV-1-pulsed DCa

| Donor | Immunization of hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice | n | Provirus copy no.b (103) | Culture p24c (ng/ml) | Human chemokine (ng/ml)d

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIP-1α | MIP-1β | RANTES | |||||

| 1 | OVA | 8 | 10.9 ± 5.2 | 60.3 ± 23.9 | NDe | ND | ND |

| HIV-1JR-CSF | 4 | <1 | <0.2 | ND | ND | ND | |

| HIV-1NL4-3 | 4 | <1 | <0.2 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 2 | OVA | 4 | 7.8 ± 4.1 | 9.5 ± 7.6 | 1.65 ± 0.47 | 1.63 ± 0.05 | 0.19 ± 0.05 |

| HIV-1JR-CSF | 4 | <1 | <0.2 | 1.16 ± 0.08 | 1.71 ± 0.14 | 0.11 ± 0.05 | |

| HIV-1NL4-3 | 4 | <1 | <0.2 | 0.62 ± 0.10 | 0.79 ± 0.29 | 0.12 ± 0.09 | |

hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice immunized with either DC-OVA or DC-AT-2-inactivated HIV-1 particles were infected with HIV-1JR·CSF. After 7 days, sera and lymphocytes recovered from spleens and peritoneal cavities of hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice were examined for HIV-1 infection and serum chemokine levels. Results are expressed as the means ± standard deviations from six independent experiments.

HIV-1 provirus copy number in fresh samples per total recovered cells from individual mice.

HIV-1 p24 concentration in supernatants of lymphocytes (106 cells/ml) cultured for 5 days.

Human chemokine concentration in serum samples as determined by ELISA.

ND, not determined.

Serum contains a suppression factor.

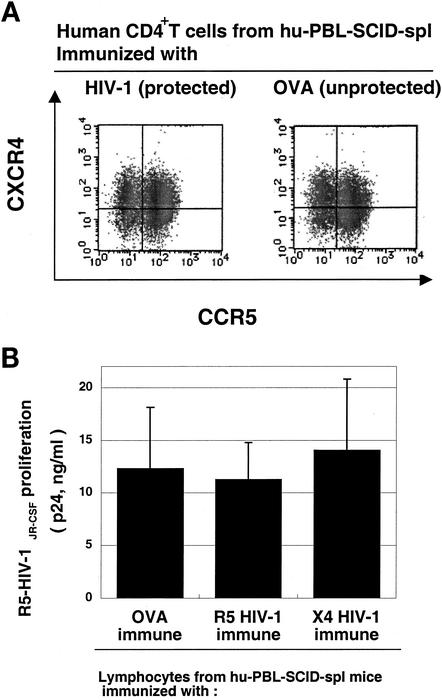

The levels of CCR5 and CXCR4 expression on the surface of human CD4+ T cells isolated from the DC-HIV-1-immunized mice (protected) were comparable to those from DC-OVA-immunized (unprotected) mice (Fig. 2A). This finding suggests that the CD4+ T cells from the protected groups were just as susceptible to R5 HIV-1 infection in vitro as those from the nonprotected mice (Fig. 2B). These data prompted us to speculate that one potential explanation for these findings could be that the HIV-1-activated human PBMC from the DC-based HIV-1 immunization induce an anti-R5 HIV-1 state in the animals without rendering the human CD4+ T cells intrinsically nonpermissive to R5 HIV-1 infection. Thus, we speculated that some soluble HIV-1 suppressive factors might be involved.

FIG. 2.

Human CD4+ T cells from HIV-1-protected hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice express CCR5 and are permissive for R5 HIV-1 infection in vitro. (A) Lymphocytes recovered from hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice immunized with DC-OVA or DC-HIV-1JR-CSF were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CCR5, and anti-CXCR4. The expression profiles of CCR5 and CXCR4 on the CD4+ T cells are shown. (B) Lymphocytes recovered from hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice immunized with DC-OVA, DC-HIV-1JR-CSF, or DC-HIV-1NL4-3 were washed and infected with 500 TCID50 of HIV-1JR-CSF at 37°C for 4 h in vitro. After washing, the cells were cultured for 5 days in RPMI medium containing 20 U of IL-2 per ml. Levels of HIV-1 p24 present in culture supernatants were quantitated by ELISA. All results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from six independent experiments.

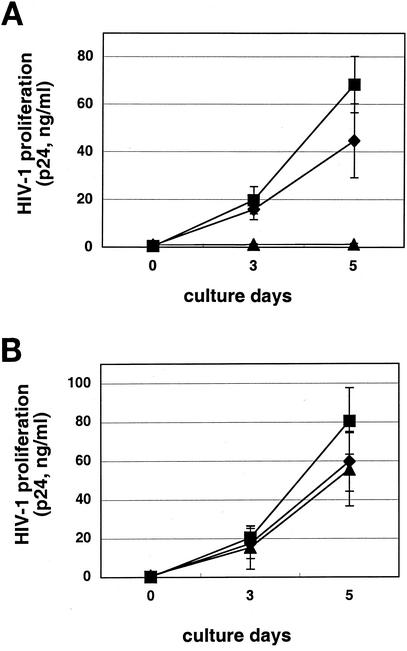

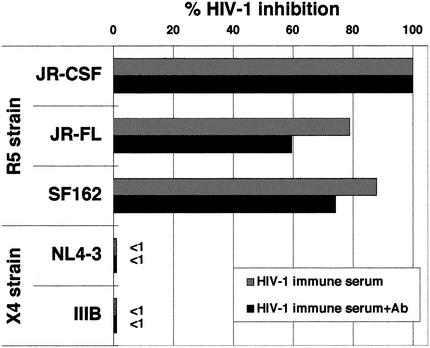

Pretreatment of R5 HIV-1 virus with serum samples from the DC-HIV-1-immunized mice did not inhibit HIV-1 infection (data not shown), suggesting that the factor is not directed against the virus itself. Therefore, target PBMC were pretreated with the immune serum samples and then infected with either R5 or X4 HIV-1, followed by washing and cultivation in IL-2-containing medium. Sera from either DC-R5 HIV-1- or DC-X4 HIV-1-immunized mice, but not those from DC-OVA-immunized mice, markedly inhibited productive infection of the PBMC with R5 HIV-1 (Fig. 3A), but not X4 HIV-1 (Fig. 3B), in vitro. As shown in Fig. 4, the DC-HIV-1-immune serum was also suppressive for infection of the PBMC with the other two R5 HIV-1 isolates but not for infection with the X4 HIV-1 isolates. It is important to note that the R5 HIV-1-suppressive activity was not reversed by the addition of a mixture of antibodies against the three β-chemokines (Fig. 4). The antibody mixture at the concentration utilized (10 μg/ml for each of the three antibodies) was shown to be capable of neutralizing the anti-R5 HIV-1 effect of the cocktail of the three corresponding β-chemokines at 100 ng/ml each (data not shown). In addition, the putative factor also suppressed infection of human macrophage cultures with the three R5 HIV-1 strains, as determined by the absence of proviral DNA (Fig. 5). The HIV-1-suppressive activity neither was associated with cell death nor was MHC restricted (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of R5 (A), but not X4 (B), HIV-1 infection by the HIV-1 immune serum. PBMC (5 × 105 cells/well) activated in vitro for 3 days were washed and then incubated in medium (▪) or final 20% serum samples obtained from either DC-OVA-immune (⧫) or DC-HIV-1JR-CSF-immune (▴) hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice at 37°C for 1 h, followed by the addition of 500 TCID50 of HIV-1JR-CSF or HIV-1NL4-3 and further incubation at 37°C for 4 h. After washing, cells were incubated in IL-2-containing medium for 5 days. The level of HIV-1 replication was monitored by quantitating HIV-1 p24 levels in the culture supernatants. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from six independent experiments.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of R5, but not X4, HIV-1 by the HIV-1 immune serum. In vitro-activated PBMC were treated at 37°C for 1 h with 10% pooled serum samples obtained from DC-HIV-1JR-CSF-immune hu-PBL-SCDI-spl mice, followed by the addition of 500 TCID50 of HIV-1 (R5 isolates JR-CSF, JR-FL, and SF162 and X4 isolates NL4-3 and IIIB) and further incubation at 37°C for 4 h. After washing, cells were incubated in IL-2-containing medium for 5 days, and levels of HIV-1 p24 in the culture supernatants were quantitated. The HIV-1-suppressive activities of the serum preincubated with the mixture of anti-β-chemokine antibodies (+Ab) were also determined. Percent inhibition was calculated by using values obtained with the medium controls, as follows: JR-CSF, 18.7 ng/ml; JR-FL, 7.6 ng/ml; SF162, 6.6 ng/ml; NL4-3, 18.3 ng/ml; and IIIB, 10.2 ng/ml.

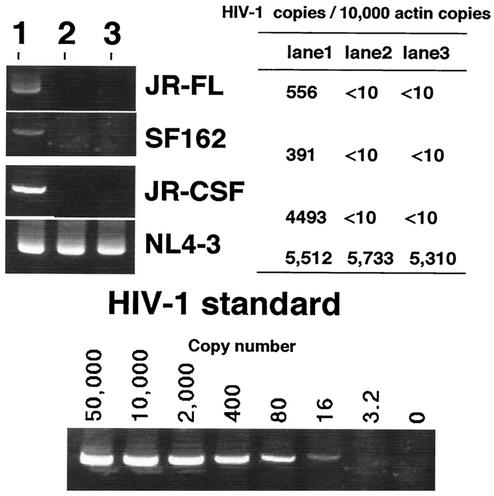

FIG. 5.

Blocking of R5 HIV-1 infection in human macrophage cultures. Cultured macrophages or activated PBMC were preincubated in medium alone (lane 1) or with pooled serum samples from DC-HIV-1JR-CSF-immune SCID mice in the absence (lane 2) or presence (lane 3) of a mixture of anti-β chemokines, and then the macrophages were infected with R5 HIV-1 strains (JR-FL, SF-162, and JR-CSF) and the PBMC were infected with X4 HIV-1NL4-3. After washing, the cells were cultured for 2 days and cellular DNA were extracted and analyzed for the number of HIV-1 provirus copies. The signal obtained for actin was utilized as a reference control. The estimated numbers of HIV-1 copies per 10,000 copies of actin are shown in the accompanying table. The data shown are representative of those from three independent experiments.

The R5 HIV-1-suppressive activity of the serum was eliminated by heating at 56°C for 30 min, suggesting the unlikelihood of the involvement of HIV-1-neutralizing antibody or IFN-α/β. Removal of serum IgG with protein G-Sepharose did not affect the suppressive activity of the serum (data not shown). The average levels of human cytokines in the sera from the DC-HIV-1-immunized mice were as follows: IFN-α, <10 pg/ml; IFN-β, 20 pg/ml; IL-4, <10 pg/ml; IL-12, <10 pg/ml; IL-13, <10 pg/ml; IL-16, <10 pg/ml; TNF-α, <10 pg/ml; and TGF-β, <10 pg/ml. These data indicate that the serum R5 HIV-1-suppressive activity is mediated by some unknown cytokine(s) of either human or mouse origin.

Human CD4+ T cells produce the suppression factor.

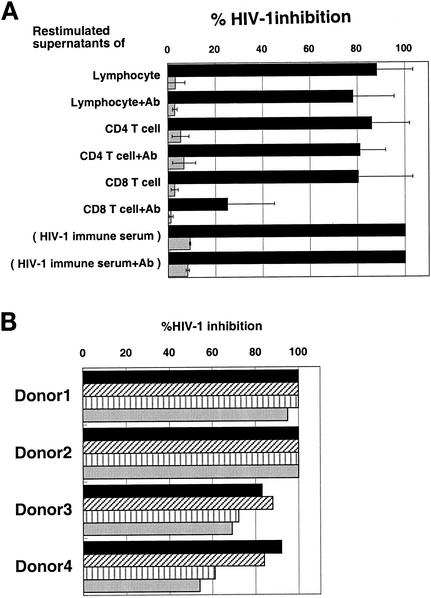

In order to define the cell lineage origin of the suppressor factor, human lymphocytes from DC-HIV-1- and DC-OVA-immunized mice were fractionated into human CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subpopulations by positive selection with antibody-bound magnetic beads. Such enriched populations of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and the unfractionated PBMC as a control were restimulated in vitro with inactivated HIV-1 and OVA, respectively, in the presence of autologous APC. As shown in Fig. 6A, the human CD4+ T cells from the DC-HIV-1-immunized mice produced a significant amount of the putative HIV-1 suppressor factor(s), which was not reversed by the addition of previously defined neutralizing anti-β-chemokine antibodies. The human CD8+ T cells, on the other hand, also produced R5 HIV-1 suppression factor, but in this case, the suppressive activity was significantly reversed by the addition of the anti-β-chemokine antibodies. Again, none of these samples were suppressive to X4 HIV-1 infection. The finding of suppressor factor synthesis by CD4+ T cells was highly reproducible, since DC-HIV-1-immune CD4+ T cells obtained from the other hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice transplanted with PBMC from four different donors also produced a similarly functioning HIV-1 suppressor factor (Fig. 6B). Since the culture supernatants of OVA-stimulated human CD4+ T cells from the DC-OVA-immunized mice had no or low R5 HIV-1-suppressive activity (data not shown), this suggested that the human CD4+ T cells reactive to HIV-1 antigen are the major producers of the suppressor factor.

FIG. 6.

Identification of the cell population producing the suppressive factor. (A) Lymphocytes from DC-HIV-1JR-CSF-immune hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice were positively selected into human CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subpopulations by using anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 MAb-conjugated immunobeads. Unfractionated (lymphocytes) or CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell populations (2 × 106 cells) were cocultured with autologous APC (2 × 105 cells) in the presence of AT-2-inactivated HIV-1 (containing 40 ng of p24) in 1 ml of IL-2-containing medium. After 2 days, culture supernatants were harvested to quantitate the levels of HIV-1 suppressor activity. Activated PBMC (target cells) were pretreated with these culture supernatants (50% final concentration) in the absence or presence (+Ab) of a mixture of anti-β-chemokine neutralizing antibodies and then infected with 500 TCID50 of either HIV-1JR-CSF (solid bars) or HIV-1NL4-3 (shaded bars). After washing, the PBMC were cultured for 5 days, and HIV-1 p24 produced in the culture supernatants was measured. DC-HIV-1-immune serum (20%) was used as a positive control. The percent inhibition was calculated by utilizing the values obtained for the medium controls, which were 19.4 ng/ml for JR-CSF and 25.9 ng/ml for NL4-3. All results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from six independent experiments. (B) Immune serum samples (20%) and culture supernatants (50%) of in vitro-restimulated CD4+ T cells, which were prepared as described above from the DC-HIV-1JR-CSF-immune hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice reconstituted with PBMC and DC from four different donors, were examined for suppressive activity against HIV-1JR-CSF infection of PBMC as described above. p24 values in the infected PBMC cultures were determined on day 5, and the percent HIV-1 inhibition was calculated by utilizing the p24 value obtained with the medium control, which was 23.4 ng/ml. Solid bars, immune serum; diagonally hatched bars, serum pretreated with a mixture of anti-β-chemokine antibodies; vertically hatched bars, restimulated culture supernatants; shaded bars, restimulated culture supernatants pretreated with a mixture of anti-β-chemokine antibodies.

Partial characterization of the suppression factor.

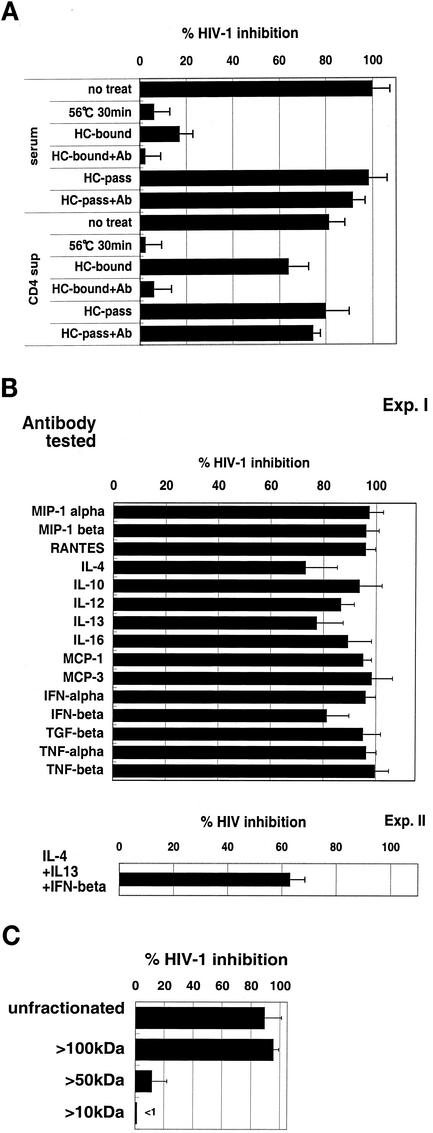

The HIV-1 suppressor factor produced by the DC-HIV-1-immune serum and the restimulated CD4+ T-cell culture supernatants were further characterized. As shown in Fig. 7A, the suppressive activity was eliminated by heating at 56°C for 30 min, was not absorbed by passage through a heparin-Sepharose column, and was not reversed by incubation with the anti-β-chemokine antibodies. It is important to note that the same CD4+ T-cell cultures also did produce heparin-binding R5 HIV-1-suppressive factors. However, these were neutralized by the addition of the β-chemokine antibodies. The antibody neutralization assay results shown in Fig. 7B show that the factor was not likely to be related to the CCR5-binding β-chemokines IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IL-16, MCP-1, MCP-3, IFN-α, IFN-β, TNF-α, and TNF-β. Thus, although the antibodies against IL-4, IL-13, and IFN-β showed marginal neutralizing activity, a mixture of these antibodies did not synergistically block the biological suppressor activity of the factor.

FIG. 7.

Partial characterization of the HIV-1 suppressor factor. (A) The HIV-1 immune serum and in vitro-restimulated culture supernatants from DC-HIV-1JR-CSF-immune hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice were heated at 56°C for 30 min or separated into heparin-binding andnonbinding fractions by passage of the serum or supernatant fluid through heparin-Sepharose columns (HC). The heparin-bound fraction was eluted with 2 M NaCl buffer. Thereafter, activated PBMC were pretreated with these samples (at final concentrations of 20% serum and 50% culture supernatants) in the absence or presence (+Ab) of a mixture of anti-β-chemokine antibodies and then infected with 500 TCID50 of HIV-1JR-CSF. After 5 days, the p24 level in each culture supernatant was calculated. The percent inhibition was calculated by using the p24 value obtained with the medium control, which was 22.3 ng/ml. (B) Pooled sera (10%) from the DC-HIV-1JR-CSF-immune hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice were preincubated with each anti-human cytokine antibody at 10 μg/ml and then examined for suppressor activity against HIV-1JR-CSF infection of PBMC. In experiment (Exp.) II, the immune serum was pretreated with a mixture of anti-IL-4, anti-IL-13, and anti-IFN-β for 1 h before its addition to activated PBMC, and the PBMC were then infected with HIV-1JR-CSF as described above. The p24 value for the medium control was 20.0 ng/ml. (C) Pooled sera from the DC-HIV-1JR-CSF-immune hu-PBL-SCID-spl mice were passed through the HC column, and then aliquots were filtered through 100-, 50-, and 10-kDa-cutoff Centricon filters. The filtrates obtained were examined for suppressive activity against HIV-1JR-CSF infection of PBMC at a 10% concentration. The data presented are representative of those from four independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

We next examined the molecular size of the factor. The pooled sera from the DC-HIV-1-immunized mice were depleted of β-chemokines by use of heparin-Sepharose and fractionated by serial centrifugation over different molecular sieving filters. Figure 7C shows that the anti-HIV-1 suppressor factor was present in the >100-kDa fraction. Similar results were obtained with the analysis of the in vitro-restimulated DC-HIV-1-immune CD4+ T-cell culture supernatants (data not shown).

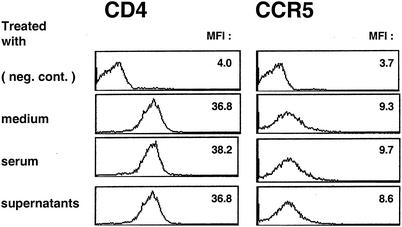

The fact that the putative suppressor factor did not down-regulate CCR5 expression on macrophages provides support for the notion that this newly identified HIV-1 suppressor factor does not belong to the CCR5-binding β-chemokine family (Fig. 8). In addition, as mentioned above, the factor did not affect CD4 expression (Fig. 8). These observations suggest that the factor suppresses R5 HIV-1 infection without affecting HIV-1 receptor expression.

FIG. 8.

The suppressor factor has no detectable effect on the levels of CCR5 and CD4 expression by macrophages. Macrophages cultured for 5 days with M-CSF were treated with either the immune serum (10%) or the in vitro-restimulated CD4+ T-cell culture supernatants (50%) generated from the DC-HIV-1JR-CSF-immune hu-PBL-SCID mice at 37°C for 1 h. The cells were FcR blocked and stained with anti-CD4 and -CCR5. The data shown are representative of those from four independent experiments. MFI, mean of fluorescence intensity.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we showed for the first time that immunization of hu-PBL-SCID mice with HIV-1-pulsed mature DC protected the mice against R5 HIV-1 infection and that the protection was at least partially mediated by a soluble factor(s) present in the serum produced predominantly by human immune CD4+ T cells in response to either R5 or X4 HIV-1 antigen.

It is possible that the DC-HIV-1-immune CD8+ T cells from these mice also produce R5 HIV-1 suppression factors in addition to the previously characterized anti-R5 HIV-1 β-chemokines and CD8 factors known as Cd8 antiviral factors (CAF). However, since the immune CD4+ T cells always produced relatively higher levels of the β-chemokine-independent R5 suppression factor than comparable numbers of immune CD8+ T cells in vitro, we assume that the major producer of the novel factor is the CD4+ T-cell population rather than the CD8+ T-cell population in our hu-PBL-SCID-spl system. While the present in vitro restimulation experiments showed that the DC-HIV-1-immune CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells were capable of producing the previously defined β-chemokines in response to HIV-1 antigen, the levels of these chemokines in the immune serum were lower than those required for suppression of R5 HIV-1 infection. In addition, two other facts make it unlikely that the factor described here contains β-chemokines. First, the CD4+ T cells recovered from the protected mice expressed high levels of CCR5, similar to those from the unprotected mice. Second, the immune serum incubated with the macrophages did not induce any detectable down-modulation of CCR5 expression by such macrophages. We submit that such findings support the view that the CCR5-binding β-chemokines are not the major R5 HIV-1-suppressive factor in vivo. However, it is clearly possible that these β-chemokines produced by the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subpopulations may work synergistically in vivo with the newly identified antiviral factor described here.

To elicit the anti-R5 HIV-1 status in the hu-PBL-SCID mice, it was necessary to immunize the mice at least twice with HIV-1-pulsed autologous mature DC by i.s. injection. The HIV-1 suppression was mediated by a noncytolytic mechanism. It appears that the production of the suppressor factor is HIV-1 antigen dependent but virus isolate independent and that close contact between naive CD4+ T cells and HIV-1 antigen presented by DC in the secondary lymphoid organs of mice facilitates the primary human anti-HIV-1 T-cell immune responses. The advantage of direct inoculation of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) antigen into the lymph nodes, where mature DC reside, to induce a protective immune response has been demonstrated in the simian model (13, 14). Since DC-HIV-1-immunized PBMC specimens from five different healthy individuals produced the HIV-1 suppressor factor, it appears that the factor production is not influenced by MHC background. These observations, together with the finding that the suppressor factor can be induced in a relatively short period (10 days from the initial immunization), indicates that the present DC-HIV-1 immunization protocol may be useful for the potential induction of an immediate protective immune response in HIV-1-infected humans.

The induction of primary HIV-1-specific human immune responses in vitro (37) and in hu-PBL-SCID mice in vivo (9, 10) by DC-based immunization has been achieved. In each case, the key issue is the use of experimentally matured DC. IFN-α/β and CD40L have been demonstrated to be DC maturation factors which induce expression and/or enhanced expression of antigen-presenting MHC class I and II molecules and costimulatory molecules. Unfortunately, it has not been reported so far whether the induced anti-HIV-1 T-cell immune responses in these studies were protective against HIV-1 infection in vivo. In the present study, we have also confirmed that the use of the HIV-1-pulsed mature DC is essential for induction of the anti-HIV-1 status in SCID mice. This view is supported by the finding that human CD4+ T cells in DC-OVA-immunized mice did not produce the suppressor factor in vitro. These findings also suggest that the priming of HIV-1-reactive, naive CD4+ T cells by sufficient numbers of HIV-1-pulsed DC is essential for the production of the putative suppressor factor in vivo.

The precise identity of this newly defined putative suppressor factor remains to be identified, as does the nature of the HIV-1 antigen which is responsible for the induction of the factor. The approximate equal immunogenicities of R5 and X4 HIV-1 virions in the induction of the HIV-1 suppressor factor suggest that the V3 region of the Env gp120 that defines the selective tropism of the virus for the X4 and R5 receptors and the viral nonstructural proteins are not likely to be involved. Coculture of the HIV-1-immune CD4+ T cells with truncated HIV-1 proteins an/or the use of synthetic overlapping HIV-1 peptides may help in the mapping of the HIV proteins and/or peptides that are potential inducers of this newly defined suppressor factor. From a therapeutic perspective, it will be of interest to determine whether the factor can be produced from CD4+ T cells from HIV-1-infected individuals upon HIV-1 antigen stimulation in vivo and in vitro.

The mechanism for HIV-1 suppression by the present factor appears to be at the level of inhibition of an early stage of virus infection. The preferential suppression of R5 HIV-1 in activated primary PBMC cultures and macrophages in vitro suggests that the factor may belong to the CCR5-binding β-chemokines. However, several findings discount this possibility. These include the findings that (i) the concentrations of MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES in the DC-HIV-1-immune serum samples were too low to suppress HIV-1 in vitro; (ii) neutralizing antibodies against the three human β-chemokines did not reverse the suppressive activity; and (iii) the suppressor factor was not absorbed by a heparin-Sepharose column. These findings strongly suggest that the factor is not related at least to these groups of β-chemokines. Furthermore, the fact that the levels of expression of CCR5 and CD4 on macrophages after treatment with the factor did not change appreciably diminishes the possible relationship between the factor and the CCR5-binding β-chemokines. The other cytokines known to suppress R5 HIV-1 proliferation in primary macrophages are the Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-10 (21) and the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α (11) and IFN-γ (5, 35). However, the involvement of these cytokines in the present studies of R5 HIV-1 suppression is less likely, since blocking antibodies against these cytokines did not interfere significantly with the suppressive activity under the present assay conditions. The involvement of human IFN-α/β, which have been implicated in anti-HIV-1 protective activity in SCID mice (12), is also unlikely, since X4 HIV-1 infection of PBMC was not suppressed by the factor under the same experimental conditions. Since neutralizing antibodies against IL-4, IL-10, and IFN-β alone or in combination showed a marginal blocking effect (20 to 35%) against the present factor, it remains to be resolved whether IL-4, IL-10, and IFN-β, which are known to suppress R5 HIV-1, work synergistically with the present HIV-1 suppressor factor or whether the factor shares epitopes with these molecules and is thus partially cross-reactive with these cytokines. Another possibility is that certain classes of anti-HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies and/or murine serum components may be involved. However, their contribution in vivo is likely to be minimal, since the suppressive activity of the HIV-1-immune serum was heat labile and not absorbed by protein G and since fresh sera from DC-OVA-immune mice had no suppressive activity.

The characteristics of the present HIV-1 suppressor factor are also different from those of other, as-yet-undefined, HIV-1 suppressor factors. First, the present factor is predominantly, but not exclusively, produced by DC-HIV-1-immune CD4+ T cells, while the so-called CAF is produced by CD8+ T cells from HIV-1-infected individuals, and CAF inhibits both R5 and X4 HIV-1 production at the level of viral transcription (15). It is important to note that hu-PBL-SCID mice reconstituted with human PBMC from HIV-1-exposed but uninfected individuals were resistant to both R5 and X4 HIV-1 infection by a CD8+ T-cell-dependent mechanism (36). However, it has not been reported whether the anti-HIV-1 effect in these studies was mediated by the CCR5-binding chemokines or CAF. Although it remains unclear whether the factor exists either as a monomer, as an aggregate, or bound to serum proteins, the high molecular size of the present factor argues against a relationship of this newly identified factor to the human defensins α1, α2, and α3, which have recently been demonstrated to be produced by human CD8+ T cells and to block both R5 and X4 HIV-1 infection of activated PBMC (36). Another CAF candidate is the modified form of bovine anti-thrombin III that is produced by CD8+ T cells from HIV-1-infected individuals (6). This molecule is heat stable, 40 kDa by gel filtration, and suppressive to both X4 and R5 HIV-1 infection of cell lines and is thus clearly different from the present factor. Similarly, differences in molecular size and HIV-1 selectivity in suppression suggest that the present factor is distinct from the secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor that is a potent anti-HIV-1 factor in saliva (19) and from soluble poly anions such as dextran sulfate, heparin, or heparan sulfate, which interfere with CD4- and coreceptor-independent HIV-1 attachment to the cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans (29). It has previously been shown that the induction of β-chemokine-independent intrinsic resistance of CD4+ T cells to R5 HIV-1 infection can be achieved in vitro by stimulation of CD4+ T cells with a combination of anti-CD3- and anti-CD28-conjugated immunobeads (25). Furthermore, it has been shown that naive, but not memory, CD4+ T cells from HIV-1-negative donors become resistant to R5 HIV-1 upon dual stimulation with anti-CD3 MAb and either anti-CD28 MAb or CD80 independently of CCR5-binding chemokines (20). Although these CD4+ T cells could suppress R5 HIV-1 replication in activated memory CD4+ T cells, it remains unclear whether these stimulated naive CD4+ T cells secrete HIV-1 suppressor factors identical to the present factor.

In conclusion, the present study has demonstrated for the first time that a DC-based HIV-1 vaccination can induce HIV-1-reactive human CD4+ T cells to produce an as-yet-undefined R5 HIV-1 suppressor factor in hu-PBL-SCID mice. These observations, together with the recent demonstration by Lu et al. (16) that DC pulsed with AT-2-inactivated SIV can stimulate protective anti-SIV-specific T-cell and antibody responses in rhesus monkeys, suggest a rational basis for DC-based immunization against HIV-1 infection in humans.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to S. R. Jennings of Louisiana State University and A. A. Ansari of Emory University for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan; by grants for Research on HIV/AIDS and Health Sciences focusing on Drug Innovation from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan; and by grants from the Japan Human Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aaberge, I. S., T. E. Steinsvik, E. C. Groeng, R. B. Leikvold, and M. Lovik. 1996. Human antibody response to a pneumococcal vaccine in SCID-PBL-hu mice and simultaneously vaccinated human cell donors. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 105:12-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adachi, A., H. E. Gendelman, S. Koenig, T. Folks, R. Willey, A. Rabson, and M. A. Martin. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 59:284-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bombil, F., J. P. Kints, J. M. Scheiff, H. Bazin, and D. Latinne. 1996. A promising model of primary human immunization in human-scid mouse. Immunobiology 195:360-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delhem, N., F. Hadida, G. Gorochov, F. Carpentier, J. P. de Cavel, J. F. Andreani, B. Autran, and J. Y. Cesbron. 1998. Primary Th1 cell immunization against HIVgp160 in SCID-hu mice coengrafted with peripheral blood lymphocytes and skin. J. Immunol. 161:2060-2069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhawan, S., L. M. Wahl, A. Heredia, Y. Zhang, J. S. Epstein, M. S. Meltzer, and I. K. Hewlett. 1995. Interferon-gamma inhibits HIV-induced invasiveness of monocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 58:713-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geiben-Lynn, R., M. Kursar, N. V. Brown, E. L. Kerr, A. D. Luster, and B. D. Walker. 2001. Noncytolytic inhibition of X4 virus by bulk CD8+ cells from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected persons and HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes is not mediated by beta-chemokines. J. Virol. 75:8306-8316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ifversen, P., C. Martensson, L. Danielsson, C. Ingvar, R. Carlsson, and C. A. Borrebaeck. 1995. Induction of primary antigen-specific immune responses in SCID-hu-PBL by coupled T-B epitopes. Immunology 84:111-116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito, M., H. Hiramatsu, K. Kobayashi, K. Suzue, M. Kawahata, K. Hioki, Y. Ueyama, Y. Koyanagi, K. Sugamura, K. Tsuji, T. Heike, and T. Nakahata. 2002. NOD/SCID/gamma mouse: an excellent recipient mouse model for engraftment of human cells. Blood 100:3175-3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koyanagi, Y., S. Miles, R. T. Mitsuyasu, J. E. Merrill, H. V. Vinters, and I. S. Chen. 1987. Dual infection of the central nervous system by AIDS viruses with distinct cellular tropisms. Science 236:819-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koyanagi, Y., Y. Tanaka, J. Kira, M. Ito, K. Hioki, N. Misawa, Y. Kawano, K. Yamasaki, R. Tanaka, Y. Suzuki, Y. Ueyama, E. Terada, T. Tanaka, M. Miyasaka, T. Kobayashi, Y. Kumazawa, and N. Yamamoto. 1997. Primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viremia and central nervous system invasion in a novel hu-PBL-immunodeficient mouse strain. J. Virol. 71:2417-2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lane, B. R., D. M. Markovitz, N. L. Woodford, R. Rochford, R. M. Strieter, and M. J. Coffey. 1999. TNF-alpha inhibits HIV-1 replication in peripheral blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages by inducing the production of RANTES and decreasing C-C chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) expression. J. Immunol. 163:3653-3661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lapenta, C., S. M. Santini, E. Proietti, P. Rizza, M. Logozzi, M. Spada, S. Parlato, S. Fais, P. M. Pitha, and F. Belardelli. 1999. Type I interferon is a powerful inhibitor of in vivo HIV-1 infection and preserves human CD4(+) T cells from virus-induced depletion in SCID mice transplanted with human cells. Virology 263:78-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehner, T., L. A. Bergmeier, L. Tao, C. Panagiotidi, L. S. Klavinskis, L. Hussain, R. G. Ward, N. Meyers, S. E. Adams, A. J. Gearing, et al. 1994. Targeted lymph node immunization with simian immunodeficiency virus p27 antigen to elicit genital, rectal, and urinary immune responses in nonhuman primates. J. Immunol. 153:1858-1868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehner, T., Y. Wang, M. Cranage, L. A. Bergmeier, E. Mitchell, L. Tao, G. Hall, M. Dennis, N. Cook, R. Brookes, L. Klavinskis, I. Jones, C. Doyle, and R. Ward. 1996. Protective mucosal immunity elicited by targeted iliac lymph node immunization with a subunit SIV envelope and core vaccine in macaques. Nat. Med. 2:767-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy, J. A., C. E. Mackewicz, and E. Barker. 1996. Controlling HIV pathogenesis: the role of the noncytotoxic anti-HIV response of CD8+ T cells. Immunol. Today 17:217-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu, W., X. Wu, Y. Lu, W. Guo, and J. M. Andrieu. 2003. Therapeutic dendritic-cell vaccine for simian AIDS. Nat. Med. 9:27-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazingue, C., F. Cottrez, C. Auriault, J. Y. Cesbron, and A. Capron. 1991. Obtention of a human primary humoral response against schistosome protective antigens in severe combined immunodeficiency mice after the transfer of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 21:1763-1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCune, J., H. Kaneshima, J. Krowka, R. Namikawa, H. Outzen, B. Peault, L. Rabin, C. C. Shih, E. Yee, M. Lieberman, et al. 1991. The SCID-hu mouse: a small animal model for HIV infection and pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 9:399-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNeely, T. B., D. C. Shugars, M. Rosendahl, C. Tucker, S. P. Eisenberg, and S. M. Wahl. 1997. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity by secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor occurs prior to viral reverse transcription. Blood 90:1141-1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mengozzi, M., M. Malipatlolla, S. C. De Rosa, L. A. Herzenberg, and M. Roederer. 2001. Naive CD4 T cells inhibit CD28-costimulated R5 HIV replication in memory CD4 T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:11644-11649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montaner, L. J., and S. Gordon. 1995. TH2 downregulation of macrophage HIV-1 replication. Science 267:538-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mosier, D. E. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of human cells transplanted to severe combined immunodeficient mice. Adv. Immunol. 63:79-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosier, D. E., R. J. Gulizia, S. M. Baird, D. B. Wilson, D. H. Spector, and S. A. Spector. 1991. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of human-PBL-SCID mice. Science 251:791-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohteki, T., T. Fukao, K. Suzue, C. Maki, M. Ito, M. Nakamura, and S. Koyasu. 1999. Interleukin 12-dependent interferon gamma production by CD8alpha+ lymphoid dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 189:1981-1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riley, J. L., R. G. Carroll, B. L. Levine, W. Bernstein, D. C. St Louis, O. S. Weislow, and C. H. June. 1997. Intrinsic resistance to T cell infection with HIV type 1 induced by CD28 costimulation. J. Immunol. 158:5545-5553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rizza, P., S. M. Santini, M. A. Logozzi, C. Lapenta, P. Sestili, G. Gherardi, R. Lande, M. Spada, S. Parlato, F. Belardelli, and S. Fais. 1996. T-cell dysfunctions in hu-PBL-SCID mice infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) shortly after reconstitution: in vivo effects of HIV on highly activated human immune cells. J. Virol. 70:7958-7964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossio, J. L., M. T. Esser, K. Suryanarayana, D. K. Schneider, J. W. Bess, Jr., G. M. Vasquez, T. A. Wiltrout, E. Chertova, M. K. Grimes, Q. Sattentau, L. O. Arthur, L. E. Henderson, and J. D. Lifson. 1998. Inactivation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity with preservation of conformational and functional integrity of virion surface proteins. J. Virol. 72:7992-8001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santini, S. M., C. Lapenta, M. Logozzi, S. Parlato, M. Spada, T. Di Pucchio, and F. Belardelli. 2000. Type I interferon as a powerful adjuvant for monocyte-derived dendritic cell development and activity in vitro and in Hu-PBL-SCID mice. J. Exp. Med. 191:1777-1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saphire, A. C., M. D. Bobardt, Z. Zhang, G. David, and P. A. Gallay. 2001. Syndecans serve as attachment receptors for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 on macrophages. J. Virol. 75:9187-9200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shioda, T., J. A. Levy, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 1991. Macrophage and T cell-line tropisms of HIV-1 are determined by specific regions of the envelope gp120 gene. Nature 349:167-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subramani, S., R. Mulligan, and P. Berg. 1981. Expression of the mouse dihydrofolate reductase complementary deoxyribonucleic acid in simian virus 40 vectors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1:854-864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki, Y., Y. Koyanagi, Y. Tanaka, T. Murakami, N. Misawa, N. Maeda, T. Kimura, H. Shida, J. A. Hoxie, W. A. O'Brien, and N. Yamamoto. 1999. Determinant in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 for efficient replication under cytokine-induced CD4+ T-helper 1 (Th1)- and Th2-type conditions. J. Virol. 73:316-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka, T., F. Kitamura, Y. Nagasaka, K. Kuida, H. Suwa, and M. Miyasaka. 1993. Selective long-term elimination of natural killer cells in vivo by an anti-interleukin 2 receptor beta chain monoclonal antibody in mice. J. Exp. Med. 178:1103-1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tary-Lehmann, M., A. Saxon, and P. V. Lehmann. 1995. The human immune system in hu-PBL-SCID mice. Immunol. Today 16:529-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaitseva, M., S. Lee, C. Lapham, R. Taffs, L. King, T. Romantseva, J. Manischewitz, and H. Golding. 2000. Interferon gamma and interleukin 6 modulate the susceptibility of macrophages to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Blood 96:3109-3117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang, L., W. Yu, T. He, J. Yu, R. E. Caffrey, E. A. Dalmasso, S. Fu, T. Pham, J. Mei, J. J. Ho, W. Zhang, P. Lopez, and D. D. Ho. 2002. Contribution of human {alpha}-defensin-1, -2 and -3 to the anti-HIV-1 activity of CD8 antiviral factor. Science 26:26.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao, X. Q., X. L. Huang, P. Gupta, L. Borowski, Z. Fan, S. C. Watkins, E. K. Thomas, and C. R. Rinaldo, Jr. 2002. Induction of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell reactivity by dendritic cells loaded with HIV-1 X4-infected apoptotic cells. J. Virol. 76:3007-3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]