Abstract

Mucosal surfaces are the entry sites for the vast majority of infectious pathogens and provide the first line of defense against infection. In addition to the epithelial barrier, the innate immune system plays a key role in recognizing and rapidly responding to invading pathogens via innate receptors, such as Toll-like receptors (TLR). Bacterial CpG DNA, a potent activator of innate immunity, is recognized by TLR9. Here, we confirm that local mucosal, but not systemic, delivery of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) to the genital tract protects mice from a subsequent lethal vaginal herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) challenge. Since these effects were so local in action, we examined the genital mucosa. Local delivery of CpG ODN induced rapid proliferation and thickening of the genital epithelium and caused significant recruitment of inflammatory cells to the submucosa. Local CpG ODN treatment also resulted in inhibition of HSV-2 replication but had no effect on HSV-2 entry into the genital mucosa. CpG ODN-induced protection against HSV-2 was not associated with early increases in gamma interferon (IFN-γ) secretion in the genital tract, and CpG ODN-treated IFN-γ−/− mice were protected from subsequent challenge with a lethal dose of HSV-2. Treatment of human HEK-293 cells transfected with murine TLR9 showed that the antiviral activity of CpG ODN was mediated through TLR9. These studies suggest that local induction of mucosal innate immunity can provide protection against sexually transmitted infections, such as HSV-2 or possibly human immunodeficiency virus, at the mucosal surfaces.

Innate immunity is a universal and evolutionarily ancient form of host defense that serves as our first line of defense against most infectious pathogens and plays a decisive role in shaping the adaptive immune response. Recognition by the innate immune system relies on a limited number of germ line-encoded receptors, including the Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which recognize conserved pathogen-associated molecular patterns shared by large groups of microorganisms for whose survival they are essential (16, 25). Recently, it was shown that TLR9 recognizes unmethylated CpG sequences (3, 6, 15), which are present at high frequency in bacterial, but not vertebrate, DNA. CpG-induced TLR9 signaling in turn activates the innate immune system, including dendritic cells, macrophages, and natural killer (NK) cells, which produce Th1 cytokines, chemokines, and costimulatory molecules that facilitate the generation of adaptive immune responses (2, 18).

Mucosal surfaces serve as the entry sites for the majority of infectious pathogens and provide the first line of defense against infection. Despite this, we do not have a good understanding of the immune mechanisms that protect mucosal surfaces against infection. This is especially true for sexually transmitted viruses, such as herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), that initiate infection at the genital mucosa. Previous studies (1, 4, 7, 12, 13, 26, 28) have shown that innate mechanisms, such as NK cells, neutrophils, macrophages, complement, and natural antibodies, are involved in innate defense against HSV infections. In addition, a mouse model employing intravaginal (IVAG) immunization with attenuated HSV-2 has been used to demonstrate the importance of T-cell-mediated adaptive immune responses, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and local antibodies in protection of immunized mice against vaginal HSV-2 infection (22, 23, 28, 30-32).

Although currently many efforts are devoted to better understanding adaptive immune responses at mucosal sites and to eliciting protection against infectious diseases by induction of adaptive immunity, activation of innate immune mechanisms to provide protection against mucosal infections has not yet been exploited. Since CpG is a potent activator of innate immunity, it has been examined for its ability to act alone to prevent or treat various infections. Early studies showed that delivery of CpG DNA as late as 20 days after lethal infection with Leishmania major induced resistance that was associated with interleukin-12 and IFN-γ production (34, 36, 37). Pretreatment of mice with CpG protected them against infection with Listeria monocytogenes (21), Francisella tularensis (8), malaria (10), and tuberculosis (17), which also appeared to be due to production of IFN-γ. Very recent studies (11, 33) have shown that mucosal delivery of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) protects mice against subsequent vaginal HSV-2 challenge.

To achieve a better understanding of the CpG ODN-induced innate protection against HSV-2, we first studied the effects of local delivery of CpG on the genital mucosa. Our results show that local delivery of CpG ODN dramatically alters the genital mucosa and inhibits HSV-2 replication in, but not entry into, the vaginal mucosa. To further clarify whether the antiviral effects of CpG ODN were mediated through TLR9 signaling, the permissivities of cell lines expressing or not expressing TLR9 to HSV-2 were examined following CpG ODN treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Six- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 female mice were purchased from Charles River Canada (St. Constant, Quebec, Canada). Six- to 8-week-old female IFN-γ−/− mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Transgenic mice containing the HSV immediate-early gene ICP4 promoter fused to the coding sequence of the β-galactosidase gene were generated as previously described (29, 35).

Viruses, cells, and reagents.

HSV-2 strain 333 was grown, and titers were determined, as previously described (24). HEK-293 cells transfected with murine TLR9 were previously described (3). Synthetic CpG phosphorothioate ODN (1826) and control ODN (1982) were provided by Coley Pharmaceutical Group (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada). Antibodies against murine NK-1.1, CD11b, CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD69 and human proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) were purchased from Pharmingen (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). X-Gal (5-bromo 4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) was purchased from MBI Fermentas (Burlington, Ontario, Canada), and reagents for reverse transcription-PCR and PCR were purchased from Invitrogen (Burlington, Ontario, Canada).

Construction of recombinant HSV-2 expressing GFP.

The HSV2 green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing recombinant was constructed using a 3.2-kb XhoI fragment of HSV-2 strain 333 containing the 3′ ends of both UL27 and UL26. At an AgeI site between the polyadenylation sites of the two genes, a cassette was inserted consisting of the GFP gene (EGFP; Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) under the control of the elongation factor 1-alpha promoter and the Escherichia coli guanosine-hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase gene under the control of the mouse phosphoglycerate kinase promoter. To construct the recombinant virus, 10 μg of plasmid was digested with XhoI, extracted with an equal volume of phenol-CHCl3, precipitated with 2.5 volumes of ethanol, and resuspended in 20 μl of Tris-EDTA. The DNA was transfected into Vero cells by electroporation, and the cells were infected with HSV-2 strain 333 at a multiplicity of infection of 3 to 5 1 day posttransfection. Three days postinfection, recombinant virus from these cultures was purified by two rounds of picking GFP-positive plaques and two rounds of limiting-dilution cloning of GFP-positive virus.

Genital herpes inoculation and vaginal virus titration.

Six- to 8-week-old mice were injected subcutaneously with 2 mg of progesterone/mouse (Depo-Provera; Upjohn, Don Mills, Ontario, Canada). Five days later, the mice were anesthetized using ketamine-xylazine, placed on their backs, and infected IVAG with lethal doses of HSV-2, which were different in each stain, in 10 μl of phosphate-buffered saline for at least 45 min while being maintained under anesthetic. Vaginal washes were collected daily after infection by twice pipetting 30 μl of phosphate-buffered saline into and out of the vagina six to eight times. Viral titers in vaginal washes were determined by plaque assay on Vero cell monolayers as described previously (24). To study the effects of vaginal delivery of CpG ODN, 4 days after mice were treated with progesterone (Depo-Provera), they were anesthetized and received 100 μg of CpG ODN or control ODN IVAG. Twenty-four hours later, the mice were IVAG infected with HSV-2 and were monitored daily for genital pathology and survival for up to 4 weeks and for vaginal virus titers.

Histomorphology of the genital tract and immunohistochemistry for PCNA.

To study the effects of CpG ODN on vaginal-tissue morphology, Depo-Provera-treated mice received 100 μg of CpG ODN or control ODN. After 24 h, vaginal tissue was removed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, paraffin embedded, and sectioned at 7 μm for hematoxylin-and-eosin staining. To detect proliferation of epithelial cells, vaginal-tissue sections were stained with anti-PCNA antibody using a standard immunohistochemistry method. Briefly, the sections were first deparaffinized and rehydrated and then treated for antigen retrieval with citrate buffer using a steaming jar for 20 min. The sections were then blocked with 5% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with anti-PCNA antibody (1:250 dilution). The sections were incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody (1:1,000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. A VECTASTAIN ABC-AP kit (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, Calif.) was used for color development according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sections were then counterstained with metal green.

β-Galactosidase assay.

To detect the entry of HSV-2 into vaginal epithelial cells, transgenic mice containing the HSV-2 immediate-early ICP4 promoter fused to the coding sequence of the β-galactosidase gene were treated with CpG ODN or control ODN and 24 h later were infected with wild-type or UV-inactivated HSV-2. Twenty-four hours postinfection, vaginal tissues were dissected and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound for cryostat sectioning. The X-Gal staining was performed on 8-μm-thick tissue sections as previously described (5). The stained sections were then counterstained by fast-red nuclear staining.

Staining and flow cytometry of cells isolated from vaginal tissue.

Depo-Provera-treated mice received 100 μg of CpG ODN or control ODN. After 24 h, cells from vaginal tissue were isolated as previously described (9). The cells were incubated with labeled antibody against NK1.1, CD3, CD11b, CD8, CD4, and CD69 (0.5 μg/106 cells in 100 μl of FACS buffer) at 4°C. After 1 h of incubation, the cells were washed three times with wash buffer, fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed on a Becton Dickinson FACScan.

ELISA.

To detect the presence of IFN-γ in vaginal washes from normal, treated, or infected mice, a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems; detection limit, 10 ng/ml) was used. Washes from infected mice were first incubated with disruption buffer (Organon Teknika, Durham, N.C.) for 30 min at 37°C. Samples from IFN-γ−/− mice were used as a negative control.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical differences of the viral titers were determined by analysis of variance followed by Tukey's test. The statistical significances of the survival rates were determined by the χ2 test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. An unpaired t test was used to find the significant differences in the numbers of infected cells in vaginal sections from different groups of the ICP4 transgenic mice. Student's t test was used to calculate the statistical significance of differences in cells present in the genital mucosa.

RESULTS

Vaginal, but not systemic, delivery of CpG ODN provides protection against genital HSV-2.

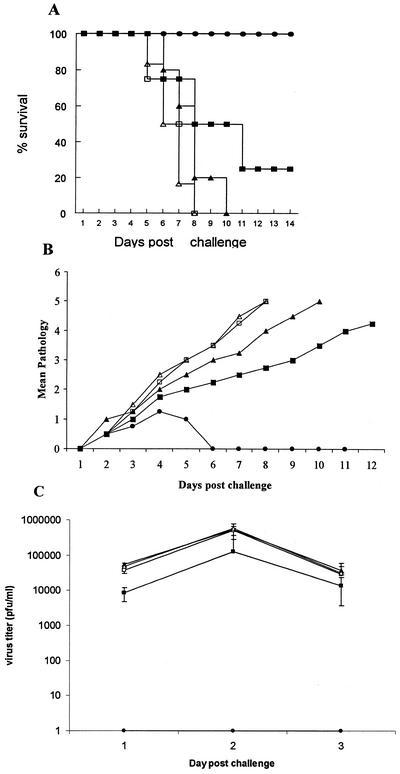

We first compared delivery of CpG ODN via local IVAG transmucosal versus intramuscular (i.m.) routes of delivery in defense against IVAG HSV-2 infection. Mice were treated IVAG or i.m. with CpG ODN or control non-CpG ODN 24 h prior to lethal IVAG HSV-2 infection. Local mucosal, but not systemic, CpG treatment resulted in complete protection against lethal HSV-2 challenge compared to non-CpG ODN-treated B6 mice (Fig. 1A). Mice treated IVAG with CpG ODN had very little or no genital pathology and virtually no HSV-2 shedding in the vaginal lumen (Fig. 1B and C). Mice treated with i.m. CpG ODN were not protected against IVAG HSV-2; they had lower HSV-2 titers in the vaginal washes only on day 1 postinfection but showed no significant differences on days 2 and 3 postinfection compared to non-CpG ODN-treated groups. These results confirm those of others (11, 33), who showed that local mucosal delivery of CpG ODN protects against genital HSV-2 infection.

FIG. 1.

Local mucosal delivery of CpG ODN protects against vaginal HSV-2 challenge. CpG ODN or control ODN was delivered vaginally or i.m. 24 h prior to lethal IVAG HSV-2 challenge (104 PFU). The challenged mice were monitored daily for genital pathology, survival, and vaginal virus titer. (A) All mice that received CpG ODN IVAG (•) were protected against lethal HSV-2 challenge compared to IVAG control ODN (▴), mice treated i.m. (with CPG [▪] or control [□] ODN), or naive (▵) mice. (B) Mice treated IVAG with CpG ODN had very low or no genital pathology compared to all other groups. Symbols are as for panel A. (C) Vaginal HSV-2 titers were examined on days 1 to 3 post-viral challenge (n = 5/group). Mice treated IVAG with CpG ODN had no detectable virus. Mice that received CpG ODN i.m. had significantly lower viral titers than did control ODN-treated or naive mice on day 1 postchallenge; there were no significant differences in the viral titers on days 2 and 3 postchallenge. Symbols are as for panel A. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

Local delivery of CpG ODN induces dramatic changes in the genital mucosa.

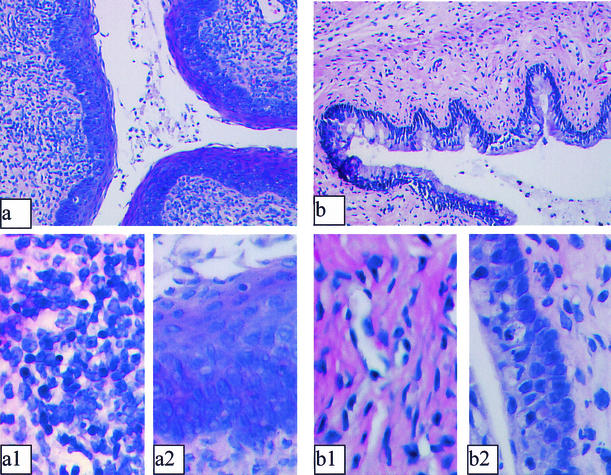

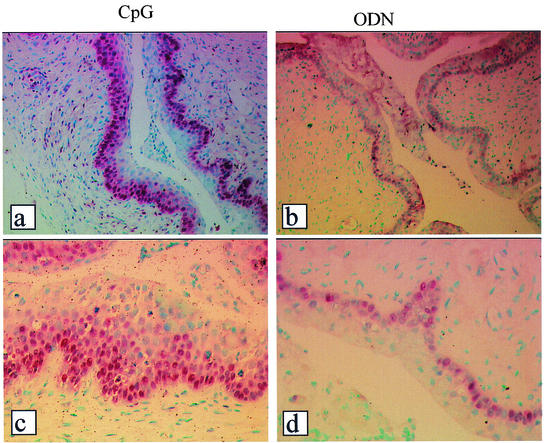

Since we observed strong innate protection against vaginal HSV-2 infection following vaginal, but not systemic, delivery of CpG ODN, we examined the histomorphology of the vaginal mucosa. Significant changes in the epithelium and submucosa of all CpG ODN-treated mice were observed compared to control non-CpG ODN-treated mice (Fig. 2). Rapid proliferation and thickening of epithelial cells were observed in all CpG-treated mice (Fig. 2a and a2). Indeed, 24 h after local delivery of CpG ODN, the vaginal epithelium thickened to an extent comparable to that seen in mice at estrus, except that the surface epithelium was not keratinized. Furthermore, significant inflammatory infiltrates were observed submucosally in CpG-treated but not control ODN-treated mice (Fig. 2a and a1 versus b and b1). Indeed, CpG-treated B6 mice demonstrated formation of lymphoid-like nodules in the genital mucosa compared to control ODN-treated mice. Induction of active proliferation of epithelial cells following CpG ODN treatment was confirmed by staining sections of vaginal tissues for PCNA (Fig. 3). Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis of inflammatory mononuclear cells from vaginal tissues of CpG-treated mice showed a significant increase in CD11b+ and NK1.1+ cells compared to control ODN-treated mice (Table 1).

FIG. 2.

CpG ODN induces rapid changes in the murine genital mucosa. Mice were treated with progesterone (Depo-Provera) and 4 days later received 100 μg of CpG ODN or control ODN IVAG. Twenty-four hours later, vaginal tissues were isolated and processed for histology. Photomicrographs representing cross-sections of vaginal tissues from CpG ODN-treated (a, a1, and a2) and control ODN-treated (b, b1, and b2) mice are shown. CpG-treated mice showed rapid proliferation and thickening of the vaginal epithelium (a and a2) compared to control ODN-treated tissues (b and b2). Significant recruitment of inflammatory cells was also observed in the submucosa of CpG-treated mice (a and a1) compared to control sections (b and b1). Magnification, ×25 (a and b) and ×500 (a1, b1, a2, and b2).

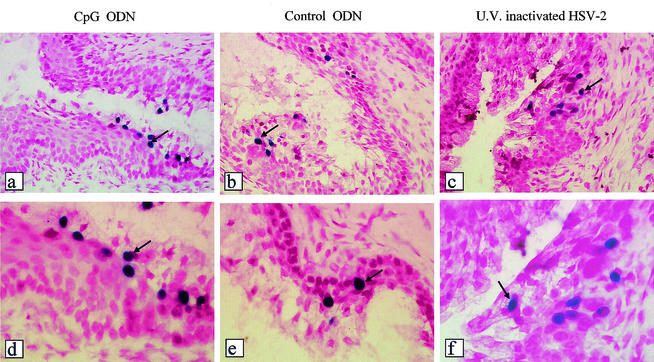

FIG. 3.

Local delivery of CpG ODN induces active proliferation of the genital epithelium. Staining for PCNA was performed to confirm the active proliferation of vaginal epithelial cells following local delivery of CpG ODN. Multiple layers of PCNA-positive cells were observed in all samples from CpG-treated mice (a and c) compared to samples from control ODN-treated mice (b and d). Magnification, ×50 (a and b) and ×250 (c and d).

TABLE 1.

FACS analysis of cells present in the vaginal mucosa following CpG ODN or control ODN treatment in B6 mice

| Antibody | % of cellsa

|

|

|---|---|---|

| CpG | ODN | |

| NK1.1 | 6.29 | 1.75 |

| CD3 | 3.70 | 5 |

| NK1.1/CD3 | 1.99 | 1.55 |

| CD8 | 3.42 | 1.55 |

| B22 | 1.41 | 3.11 |

| CD11b | 18.78 | 8 |

| CD69 | 5 | 1.53 |

Percentage of stained cells detected in an area gated for lymphocytes, granulocytes, and monocytes/macrophages. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

CpG ODN inhibits HSV-2 replication but not entry into the genital mucosa.

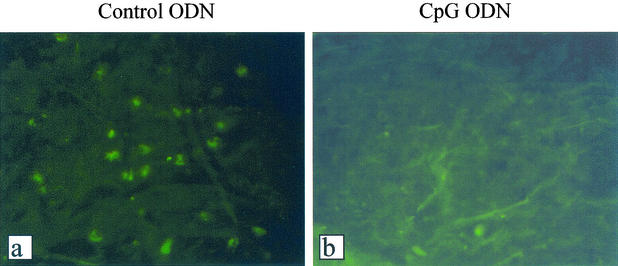

Vaginal delivery of CpG ODN resulted in very low or no viral shedding following vaginal HSV-2 challenge. To examine if HSV-2 replication was affected by CpG ODN, we first generated a recombinant HSV-2 expressing GFP. Very few or no GFP-positive cells were observed in the genital tissues of CpG ODN-treated mice compared to those of ODN-treated control mice, in which GFP-positive cells were abundant (Fig. 4). To identify whether the absence of GFP-positive cells in the CpG ODN-treated vaginal mucosa was due to inhibition of HSV-2 entry into the epithelial cells, transgenic mice containing the HSV ICP4 immediate-early gene promoter fused to the coding sequence of the β-galactosidase gene (29, 35) were challenged with HSV-2 following vaginal delivery of CpG ODN or control ODN. There were no significant differences in HSV-2 entry into the vaginal mucosa in CpG ODN-treated and control mice (Fig. 5a, b, d, and e). UV-inactivated HSV-2 was used to confirm that viral entry, but not replication, was responsible for ICP4-driven β-galactosidase expression (Fig. 5c and f).

FIG. 4.

Local delivery of CpG ODN inhibits HSV-2 replication in the genital mucosa. Depo-Provera-treated mice received 100 μg of CpG ODN or control ODN. After 24 h, the mice were vaginally infected with HSV-2 expressing GFP. Vaginal tissues were dissected 24 or 48 h postinfection and processed for histology. Virtually no GFP-positive cells were detected in the genital mucosa from CpG-treated mice (b) compared to control ODN-treated controls, which had numerous GFP-positive cells (a). The photomicrographs are representative of vaginal sections 48 h post-HSV-2 challenge. Magnification, ×250.

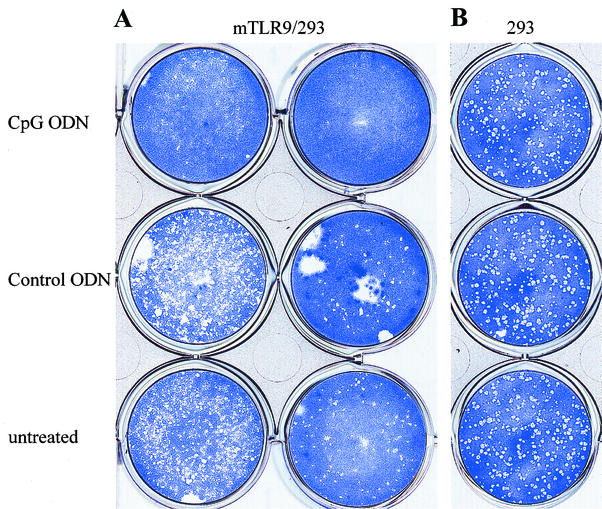

FIG. 5.

CpG ODN treatment of vaginal mucosa does not inhibit HSV-2 entry into vaginal epithelial cells. Transgenic mice containing the immediate-early HSV-2 ICP4 gene promoter fused to the bacterial β-galactosidase gene were treated IVAG with CpG or control ODN (n = 4). After 24 h, the mice were infected IVAG with HSV-2 (104 PFU). Vaginal tissues were removed 24 h postchallenge. From each vaginal tissue, 11 slides with five cross sections on each slide were prepared and processed for X-Gal staining. HSV-2 was able to enter the vaginal epithelial cells in both CpG-treated (a and d) and control ODN-treated (b and e) mice to comparable levels (with no significant differences in the mean numbers of blue cells from CpG ODN-treated and control ODN-treated mice). UV-inactivated HSV-2, proven to be replication deficient, was also able to enter the epithelial cells and activate the ICP4-driven β-galactosidase gene (c and f). The arrows indicate positive cells (ICP4 activated). Magnification, ×100 (a to c) and ×250 (d to e).

Effects of CpG ODN against genital HSV-2 occur in the absence of IFN-γ.

To determine whether CpG-induced protection against vaginal HSV-2 infection was due to induction of IFN-γ production in the genital mucosa, concentrations of IFN-γ in the vaginal washes from the knockout and B6 mice treated with CpG or control ODN were measured by ELISA. Surprisingly, there was no early induction of IFN-γ production following CpG treatment and IVAG HSV-2 challenge compared to that in control ODN-treated mice (Fig. 6A). These results were reinforced by the CpG ODN-induced protection against IVAG HSV-2 challenge in IFN-γ−/− mice (Fig. 6B and C).

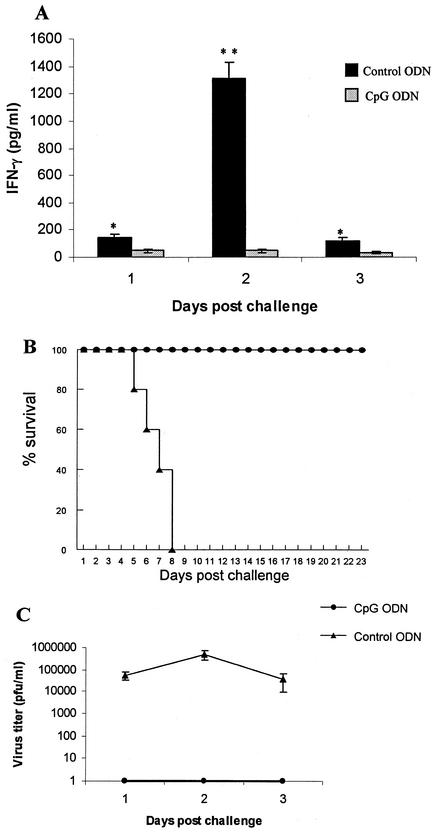

FIG. 6.

CpG ODN-induced innate protection against HSV-2 infection occurs in the absence of IFN-γ. B6 and IFN-γ−/− mice were treated IVAG with 100 μg of CpG ODN 24 h prior to HSV-2 infection. (A) No induction of early (days 1 to 3 postchallenge) IFN-γ was detected in the vaginal washes of CpG ODN-treated mice compared to control ODN-treated mice. The error bars indicate standard deviations. *P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001. (B) Local delivery of CpG ODN resulted in complete protection against subsequent challenge with a lethal dose of vaginal HSV-2 in IFN-γ−/− mice. (C) IFN-γ−/− mice treated with CpG ODN had no detectable virus in the vaginal washes compared to control ODN-treated mice.

Antiviral effects of CpG ODN are mediated through TLR9.

To study whether the antiviral effects of CpG ODN observed in the in vivo studies were due to TLR9/CpG ODN signaling, we performed in vitro studies with a cell line transformed to express murine TLR9 (mTLR9). Treatment of HEK-293 cells transfected with mTLR9 with CpG ODN resulted in significant protection (>10-fold) against HSV-2 infection in vitro (Fig. 7A and C). In contrast, HEK-293 cells that lacked murine TLR9 did not show the CpG-induced antiviral effect (Fig. 7B and C). In addition, HEK-293 cells expressing TLR9 did not inhibit HSV-2 replication when treated with control non-CpG ODN in vitro (Fig. 7A and C). No antiviral activity was detected in the supernatants of CpG ODN-treated cells against HSV-2 or vesicular stomatitis virus using a plaque assay (data not shown).

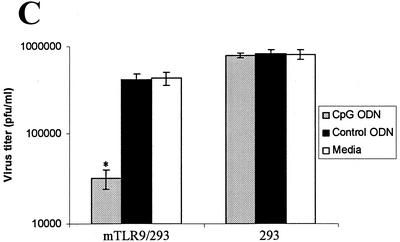

FIG. 7.

Antiviral effects of CpG are mediated through TLR9. Monolayers of HEK-293 cells transformed with murine TLR9 (A) or normal HEK-293 cells (B) were treated with CpG ODN or control ODN (25 μg/ml) or left untreated. After 24 h, the antiviral effect of CpG ODN was detected using a standard viral plaque assay with a known stock of HSV-2. (A) CpG-treated cells were significantly (>1 log unit) more resistant to HSV-2 infection in the presence of mTLR-9 than control ODN-treated or untreated cells. (B) Untransformed HEK-293 cells treated with CpG ODN showed no protection against HSV-2 infection compared to control ODN-treated or untreated cells. (C) Histogram showing significant reduction (P < 0.01) in HSV-2 titer in mTLR9-transformed HEK-293 cells following CpG ODN, but not control ODN, treatment. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

The vertebrate immune system recognizes unmethylated CpG motifs, which are prevalent in bacterial and many viral DNAs but are heavily suppressed and methylated in vertebrate genomes as “danger signals.” Synthetic ODNs containing CpG motifs mimic the immunostimulatory qualities of bacterial DNA and potently activate innate defense mechanisms, and they have been shown to provide protection against a number of infectious agents (18). Currently, the effects of CpG ODN on innate immunity are attributed to the activation of antigen-presenting cells, including dendritic cells, and subsequently activation of NK cells and production of IFN-γ (2, 19). Our results confirm very recent results of others (11, 33) showing that local delivery of CpG ODN prior to or shortly after IVAG HSV-2 infection induces a very potent innate resistance to infection. In this study, we first demonstrated that local, but not systemic, delivery of CpG ODN induced a strong innate protection against subsequent vaginal HSV-2 challenge. We then investigated the possible mechanism(s) by which CpG ODN induced this protection.

Since CpG effects were most pronounced following local mucosal delivery, we examined CpG-induced effects on genital mucosa. Vaginal epithelial cells rapidly proliferated following local delivery of CpG ODN, but not control ODN, to the vaginal mucosa. This thickening of the genital mucosa occurred extremely rapidly, within 24 h, and was comparable to the thickening observed during estrus, except that the epithelium was not keratinized. This thickening of vaginal epithelial cells might be partially responsible for the CpG-induced protection. Local delivery of CpG ODN to the vaginal mucosa also induced inflammatory infiltrates in the genital tract. Interestingly, IVAG CpG ODN treatment of normal B6 mice led to unprecedented induction of lymphoid-like nodules submucosally in the genital tract. Characterization of the infiltrating cells indicates a clear increase in cells expressing NK1.1, CD11b, or CD69 shortly after CpG treatment. Therefore, a large number of innate immune cells were rapidly mobilized to the genital tract following local delivery of CpG ODN.

Following local CpG ODN delivery, no or very low viral titers were detected in the vaginal washes, suggesting three possibilities: (i) HSV-2 enters the vaginal mucosa and replicates, but there is no shedding into the vaginal lumen; (ii) HSV-2 enters the vaginal mucosa but cannot replicate; or (iii) there is no or very little HSV-2 entry into the vaginal mucosa. Using a combination of HSV-2 expressing GFP and transgenic mice containing the immediate-early promoter of HSV ICP4 fused to the β-galactosidase gene, we showed that HSV-2 entered the vaginal mucosa of CpG ODN-treated mice comparably to that of control ODN-treated mice. However, after entry, HSV-2 did not replicate in the mucosa of the CpG ODN-treated mice. Together, these results demonstrate that CpG ODN treatment inhibited HSV-2 replication but not entry into the genital mucosa and suggest that local CpG treatment induces an antiviral state in genital epithelial and/or mucosal cells.

CpG sequences are well documented to induce Th1-type cytokines, particularly IFN-γ (20). It has been demonstrated that both an early (days 1 to 3) and late (days 5 to 7) peak of IFN-γ production occur following IVAG HSV-2 infection (27) and that they play an important role in defense against the virus (12, 14, 27, 32). In our study, CpG ODN-treated B6 mice had very low levels of IFN-γ in the vaginal washes compared to control ODN-treated or naive mice shortly after IVAG HSV-2 infection. Thus, the early peak of IFN-γ production was not observed in CpG ODN-treated mice. Additionally, CpG-induced protection against IVAG HSV-2 infection also occurred in IFN-γ−/− mice. These results suggest that CpG can act by an alternate innately induced mechanism to prevent HSV-2 infection. It is likely that local CpG treatment rapidly induces an antiviral state in the genital epithelial cells and/or cells of the mucosal tissues and that this prevents a productive infection in the genital mucosa and may explain the very low level of the early (days 1 to 3) IFN-γ in the vaginal washes.

It is well established that CpG sequences act through TLR9 to activate innate immunity (15). However, there was no previous evidence of induction of an antiviral state in cells positive for TLR9 by CpG ODN. With a cell line transfected with mTLR9, our results clearly showed that CpG/TLR9 signaling induces an antiviral state in vitro. The supernatants of the CpG ODN-treated cells had no IFN or antiviral activity (data not shown), suggesting that this activity is intracellular. Our unpublished data suggest that interleukin-15 may play an important role in this innate protection. However the exact factor(s) resulting in this antiviral state has yet to be found. It is very likely that the anti-HSV-2 effects of CpG ODN in the vaginal mucosa were also mediated through TLR9 signaling. Use of TLR9-deficient mice will provide an answer to whether the in vivo antiviral effects are dependent on or independent of TLR9 engagement.

In conclusion, the results presented in this paper confirm that local, but not systemic, delivery of CpG ODN to the genital mucosa provides significant protection against IVAG HSV-2 challenge. Further, our results show that local application of CpG ODN resulted in dramatic proliferation and thickening of the vaginal epithelium and recruitment of innate immune cells into the genital mucosa. CpG ODN treatment did not affect HSV-2 entry into genital epithelial cells but prevented replication. Our results also show that CpG ODN-induced protection can occur in the absence of IFN-γ. The CpG-induced antiviral state appeared to be dependent on TLR9 signaling, since cells that selectively express murine TLR9 were significantly protected against HSV-2 replication following CpG ODN treatment. Thus, it is likely that the CpG-induced protection against IVAG HSV-2 infection is also mediated through TLR9 signaling. Further study of the ability of CpG ODN to induce an innate antiviral state in mucosal epithelial cells may lead to the discovery of specific factors or the development of effective mucosal treatments to prevent sexually transmitted infections, such as HSV-2 or HIV disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Davis and M. McCluskie of Coley Pharmaceutical Group for provision of the CpG ODN, K. Mossman for her help in UV inactivation of HSV-2 and assessment of the replication deficiency of the UV-inactivated HSV-2, and B. Anne Croy (University of Guelph) for providing some of the IFN-γ−/− mice. We also thank J. Newton for technical support and C. Kaushic and D. DiLuca for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Institute of Infection and Immunity of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Canadian Network on Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics (CANVAC). Kenneth L. Rosenthal is the recipient of a Career Scientist Award from the Ontario HIV Treatment Network (OHTN).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler, H., J. L. Beland, N. C. Del-Pan, L. Kobzik, R. A. Sobel, and I. J. Rimm. 1999. In the absence of T cells, natural killer cells protect from mortality due to HSV-1 encephalitis. J. Neuroimmunol. 93:208-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashkar, A. A., and K. L. Rosenthal. 2002. Toll-like receptor 9, CpG DNA and innate immunity. Curr. Mol. Med. 2:545-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer, S., C. J. Kirschning, H. Hacker, V. Redecke, S. Hausmann, S. Akira, H. Wagner, and G. B. Lipford. 2001. Human TLR9 confers responsiveness to bacterial DNA via species-specific CpG motif recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:9237-9242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benencia, F., and M. C. Courreges. 1999. Nitric oxide and macrophage antiviral extrinsic activity. Immunology 98:363-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, M. A., J. W. Horner, B. R. Conklin, R. A. DePinho, D. Bok, and D. J. Zack. 2000. Tetracycline-inducible system for photoreceptor-specific gene expression. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41:4281-4287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chuang, T. H., J. Lee, L. Kline, J. C. Mathison, and R. J. Ulevitch. 2002. Toll-like receptor 9 mediates CpG-DNA signaling. J. Leukoc. Biol. 71:538-544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Da Costa, X. J., M. A. Brockman, E. Alicot, M. Ma, M. B. Fischer, X. Zhou, D. M. Knipe, and M. C. Carroll. 1999. Humoral response to herpes simplex virus is complement-dependent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12708-12712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elkins, K. L., T. R. Rhinehart-Jones, S. Stibitz, J. S. Conover, and D. M. Klinman. 1999. Bacterial DNA containing CpG motifs stimulates lymphocyte-dependent protection of mice against lethal infection with intracellular bacteria. J. Immunol. 162:2291-2298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallichan, W. S., R. N. Woolstencroft, T. Guarasci, M. J. McCluskie, H. L. Davis, and K. L. Rosenthal. 2001. Intranasal immunization with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides as an adjuvant dramatically increases IgA and protection against herpes simplex virus-2 in the genital tract. J. Immunol. 166:3451-3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gramzinski, R. A., D. L. Doolan, M. Sedegah, H. L. Davis, A. M. Krieg, and S. L. Hoffman. 2001. Interleukin-12- and gamma interferon-dependent protection against malaria conferred by CpG oligodeoxynucleotide in mice. Infect. Immun. 69:1643-1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harandi, A. M., K. Eriksson, and J. Holmgren. 2003. A protective role of locally administered immunostimulatory CpG oligodeoxynucleotide in a mouse model of genital herpes infection. J. Virol. 77:953-962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harandi, A. M., B. Svennerholm, J. Holmgren, and K. Eriksson. 2001. Differential roles of B cells and IFN-gamma-secreting CD4(+) T cells in innate and adaptive immune control of genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in mice. J. Gen. Virol. 82:845-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harandi, A. M., B. Svennerholm, J. Holmgren, and K. Eriksson. 2001. Interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-18 are important in innate defense against genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in mice but are not required for the development of acquired gamma interferon-mediated protective immunity. J. Virol. 75:6705-6709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harandi, A. M., B. Svennerholm, J. Holmgren, and K. Eriksson. 2001. Protective vaccination against genital herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection in mice is associated with a rapid induction of local IFN-gamma-dependent RANTES production following a vaginal viral challenge. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 46:420-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemmi, H., O. Takeuchi, T. Kawai, T. Kaisho, S. Sato, H. Sanjo, M. Matsumoto, K. Hoshino, H. Wagner, K. Takeda, and S. Akira. 2000. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature 408:740-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janeway, C. A., Jr., and R. Medzhitov. 2002. Innate immune recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20:197-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juffermans, N. P., J. C. Leemans, S. Florquin, A. Verbon, A. H. Kolk, P. Speelman, S. J. van Deventer, and T. van der Poll. 2002. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides enhance host defense during murine tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 70:147-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krieg, A. M. 2002. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA and their immune effects. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20:709-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krieg, A. M. 2001. Now I know my CpGs. Trends Microbiol. 9:249-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krieg, A. M. 2000. The role of CpG motifs in innate immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12:35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krieg, A. M., A. K. Yi, J. Schorr, and H. L. Davis. 1998. The role of CpG dinucleotides in DNA vaccines. Trends Microbiol. 6:23-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuklin, N. A., M. Daheshia, S. Chun, and B. T. Rouse. 1998. Role of mucosal immunity in herpes simplex virus infection. J. Immunol. 160:5998-6003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDermott, M. R., C. H. Goldsmith, K. L. Rosenthal, and L. J. Brais. 1989. T lymphocytes in genital lymph nodes protect mice from intravaginal infection with herpes simplex virus type 2. J. Infect. Dis. 159:460-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDermott, M. R., J. R. Smiley, P. Leslie, J. Brais, H. E. Rudzroga, and J. Bienenstock. 1984. Immunity in the female genital tract after intravaginal vaccination of mice with an attenuated strain of herpes simplex virus type 2. J. Virol. 51:747-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medzhitov, R., and C. A. Janeway, Jr. 2002. Decoding the patterns of self and nonself by the innate immune system. Science 296:298-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milligan, G. N. 1999. Neutrophils aid in protection of the vaginal mucosae of immune mice against challenge with herpes simplex virus type 2. J. Virol. 73:6380-6386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milligan, G. N., and D. I. Bernstein. 1997. Interferon-gamma enhances resolution of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection of the murine genital tract. Virology 229:259-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milligan, G. N., D. I. Bernstein, and N. Bourne. 1998. T lymphocytes are required for protection of the vaginal mucosae and sensory ganglia of immune mice against reinfection with herpes simplex virus type 2. J. Immunol. 160:6093-6100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell, W. J. 1995. Neurons differentially control expression of a herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early promoter in transgenic mice. J. Virol. 69:7942-7950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parr, E. L., and M. B. Parr. 1997. Immunoglobulin G is the main protective antibody in mouse vaginal secretions after vaginal immunization with attenuated herpes simplex virus type 2. J. Virol. 71:8109-8115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parr, M. B., and E. L. Parr. 1998. Mucosal immunity to herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in the mouse vagina is impaired by in vivo depletion of T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 72:2677-2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parr, M. B., and E. L. Parr. 1999. The role of gamma interferon in immune resistance to vaginal infection by herpes simplex virus type 2 in mice. Virology 258:282-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pyles, R. B., D. Higgins, C. Chalk, A. Zalar, J. Eiden, C. Brown, G. Van Nest, and L. R. Stanberry. 2002. Use of immunostimulatory sequence-containing oligonucleotides as topical therapy for genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. J. Virol. 76:11387-11396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stacey, K. J., and J. M. Blackwell. 1999. Immunostimulatory DNA as an adjuvant in vaccination against Leishmania major. Infect. Immun. 67:3719-3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taus, N. S., and W. J. Mitchell. 2001. The transgenic ICP4 promoter is activated in Schwann cells in trigeminal ganglia of mice latently infected with herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 75:10401-10408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker, P. S., T. Scharton-Kersten, A. M. Krieg, L. Love-Homan, E. D. Rowton, M. C. Udey, and J. C. Vogel. 1999. Immunostimulatory oligodeoxynucleotides promote protective immunity and provide systemic therapy for leishmaniasis via IL-12- and IFN-gamma-dependent mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:6970-6975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimmermann, S., O. Egeter, S. Hausmann, G. B. Lipford, M. Rocken, H. Wagner, and K. Heeg. 1998. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides trigger protective and curative Th1 responses in lethal murine leishmaniasis. J. Immunol. 160:3627-3630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]