Abstract

Viral entry may preferentially occur at the apical or the basolateral surfaces of polarized cells, and differences may impact pathogenesis, preventative strategies, and successful implementation of viral vectors for gene therapy. The objective of these studies was to examine the polarity of herpes simplex virus (HSV) entry using several different human epithelial cell lines. Human uterine (ECC-1), colonic (CaCo-2), and retinal pigment (ARPE-19) epithelial cells were grown on collagen-coated inserts, and the polarity was monitored by measuring the transepithelial cell resistance. Controls were CaSki cells, a human cervical cell line that does not polarize in vitro. The polarized cells, but not CaSki cells, were 16- to 50-fold more susceptible to HSV infection at the apical surface than at the basolateral surface. Disruption of the tight junctions by treatment with EGTA overcame the restriction on basolateral infection but had no impact on apical infection. No differences in binding at the two surfaces were observed. Confocal microscopy demonstrated that nectin-1, the major coreceptor for HSV entry, sorted preferentially to the apical surface, overlapping with adherens and tight junction proteins. Transfection with small interfering RNA specific for nectin-1 resulted in a significant reduction in susceptibility to HSV at the apical surface but had little impact on basolateral infection. Infection from the apical but not the basolateral surface triggered focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation and led to nuclear transport of viral capsids and viral gene expression. These studies indicate that access to nectin-1 contributes to preferential apical infection of these human epithelial cells by HSV.

Polarized epithelial cells differentially distribute proteins and lipids in the plasma membrane, creating two distinct surfaces: the apical domain, which faces the external environment, and the basolateral domain, which contacts the underlying cells and systemic vasculature (45). Both the entry and the release of viruses may be polarized, occurring selectively at either the apical or the basolateral site, and may have important implications in pathogenesis (2). Some viruses, such as simian virus 40 (7), enter polarized cells through the apical surface, while vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) and Semliki Forest virus (13, 14) preferentially enter through the basolateral domain. Most studies of viral entry have been conducted with nonpolarized cells and may not reflect in vivo conditions. For example, nonpolarized airway cells are readily susceptible to adenovirus. These findings contributed to clinical trials using adenoviral vectors for gene delivery in the treatment of cystic fibrosis. However, the clinical trials showed poor efficiency of adenoviral gene delivery. Subsequent in vitro studies with polarized airway epithelia demonstrated that the airway epithelia are highly resistant to adenoviral infection at the apical surface because of limited expression of receptors required for binding and internalization (47). Similarly, the receptors and coreceptors required for adeno-associated virus (10) entry localize preferentially to the basolateral membranes of epithelial cells (10, 48). However, the differences in binding of adeno-associated virus type 2 at the apical and basolateral membranes are insufficient to explain the variance observed in the polarity of infection. Studies suggest that polarized differences in endosomal processing and nuclear trafficking of internalized virus may also be important (11). Respiratory syncytial virus, in contrast, efficiently transduces airway epithelia via the apical surface (49). These experiences underscore the need to study microbial infection using polarized conditions that more closely model in vivo conditions.

Previous studies of HSV entry have focused predominantly on nonpolarized epithelial cell lines. These studies demonstrate that HSV entry is a complex process characterized by the following: (i) binding to heparan sulfate receptors; (ii) engagement of gD and possibly gH coreceptors; and (iii) fusion of the viral envelope with the cell membrane, leading to delivery of viral capsids to the cytoplasm (37). In some cells, endocytosis, rather than pH-independent fusion, predominates (28, 30). The penetration process requires the concerted action of the viral glycoproteins gB, gD, and gH-gL. Recent studies indicate that in human epithelial cells, such as CaSki (cervical) or CaCo-2 (intestinal), penetration is triggered by activation of signaling pathways leading to release of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ stores and phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and other cellular kinases (4, 6). The Ca2+ response facilitates penetration, whereas activation of the kinases promotes transport of viral capsids to the nuclear pore. The receptors, coreceptors, and/or signaling pathways may be preferentially sorted to the apical or basolateral membranes of polarized cells and contribute to differences in susceptibility to infection.

Several gD coreceptors have been identified, including a member of the nerve growth factor/tumor necrosis factor receptor family called HveA (herpesvirus entry mediator A), two members of the immunoglobulin superfamily, termed HveC (nectin-1δ and nectin-1α) and HveB (nectin-2α) (38), and a unique heparan sulfate sequence (36). Nectin-1 is highly expressed in human vaginal epithelium, and preincubation of HSV with recombinant nectin-1 blocks vaginal infection, suggesting that nectin may be the major coreceptor in the female genital tract (24). Previous studies suggest that nectin-1 localizes to adherens junctions in some cells, such as Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, and is not accessible for gD binding unless the junctions are disrupted (21, 38, 41). Notably, in mouse vaginal epithelium, confocal microscopy studies showed that nectin-1 localized to the apical region of the vaginal epithelial cells during diestrus, the stage of the menstrual cycle most permissive for HSV infection (24). Its localization in polarized human epithelial cells has not been extensively characterized.

Epithelial cells grown on porous supports show evidence of increased differentiation in comparison with cells grown on conventional solid surfaces (18, 31). Prior studies of HSV infection of polarized epithelia have focused primarily on HSV type 1 (HSV-1) infection of MDCK cells. HSV-1 entry has been observed from either cell surface (35, 44) or with a preference for the basolateral surface (19, 26, 34, 43). The experimental conditions for these studies varied, since some were conducted with cells grown on porous supports of various pore sizes, whereas others were conducted using cells grown on conventional plastic surfaces and differentiated apical and basolateral cells by examining infection of isolated cells or those in the periphery of islets (basolateral) compared with that of cells completely surrounded by others (apical) (34). Confluent MDCK cells, however, are relatively resistant to HSV infection, with an efficiency of infection ∼100- to 1,000-fold lower than that for other cell lines (35). Conflicting results have also been reported with respect to polarized infection of CaCo-2 cells. HSV-1 infected the apical surfaces of CaCo-2 cells with ∼10-fold-greater efficiency than the basolateral surfaces in one study (17), but the cells displayed various susceptibilities depending on the number of days in culture in another study (26). Differences between these studies may reflect, in part, differences in the species (canine versus human) and the experimental design. In addition, a critical experimental limitation in studies with cells grown on filters is the differential access to the basolateral surface due to the geometry of the system. To overcome this limitation, we modified the experimental approach and have compared susceptibilities to HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection for polarized epithelial cells infected at the apical and inverted basolateral surfaces. Using this experimental design, the contact between the virus and the cell membrane at the two surfaces is comparable. Our findings demonstrate that HSV preferentially infects the apical membrane of these human epithelial cells and that access to nectin contributes to this apical predilection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Human retinal epithelial cells (ARPE-19 and CRL-2302), human intestinal epithelial cells (CaCo-2 and HTB-37), and human cervical epithelial cells (CaSki and CRL-1550) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), and human uterine epithelial cells (ECC-1) were a gift from Charles Wira (Dartmouth Medical College, Lebanon, NH) (33). CaSki cells and CaCo-2 cells were maintained and propagated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California) supplemented with 10% or 20% fetal bovine serum, respectively, and penicillin-streptomycin. ARPE-19 and ECC-1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium-F12 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. All cells were plated on 0.4-μm-pore-size, 12-mm-diameter collagen-coated Transwell inserts (Costar, Corning, Corning, NY) at a density of 2.0 × 105 cells/insert, and the medium was changed every 2 to 3 days. Viral strains were HSV-2 (G), a well-characterized laboratory strain, and HSV-1 (K26GFP), which contains a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-VP26 fusion protein. K26GFP was a gift from P. Desai (The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) (8). Vesicular stomatitis virus-Indiana (provided by P. Palese, Mount Sinai School of Medicine) was grown on Vero cells.

Prior to infection, the transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) was measured using an epithelial Voltohmmeter (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). The net resistance was calculated by subtracting the background resistance and multiplying the resistance by the surface area of the filter. CaCo-2 cells attained a TER of ∼200 to 500 Ω · cm−2 by 10 days. ECC-1 attained a TER of ∼300 Ω · cm−2 in the same time frame, and ARPE attained ∼50 to 100 Ω · cm−2 in 20 days. CaSki cells did not form tight junctions when grown to confluence (TER values were ∼ background levels).

Plaque assays.

Cells were grown to confluence in a Transwell culture system and were exposed to serial dilutions of HSV-2 (G), HSV-1 (K26GFP), or VSV at the apical or inverted basolateral surface for 1 h at 37°C. The cells were then washed once with serum-free medium and overlaid with serum-free medium containing 0.5% methylcellulose. Plaques were counted 48 h postinfection (p.i.) by black plaque immunoassay with a gD-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) (AB1103; 1:250; Virusys) (20). VSV plaques were quantified by Giemsa staining.

Confocal microscopy.

Cells were grown to confluence in a Transwell culture system and were infected from either the apical or inverted basolateral surfaces with 100 μl of HSV-2 (G) or HSV-1 (K26GFP) at 37°C for 1 h. Unbound virus was removed by three washing three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), either the inserts were processed for confocal imaging immediately or fresh serum-free medium was added to both chambers (0.5 ml on the upper chamber and 1.5 ml in the lower chamber) and cells incubated for various times before processing. To label plasma membranes, cells were stained for 30 min with EZ-Link sulfosuccinimidobiotin reagent (1:1,000 dilution; Pierce), which reacts with primary amines on cell surface proteins prior to fixation; after fixation with 4% of paraformaldehyde, cells were permeabilized by incubation with 1% of Triton in PBS for 5 min at room temperature. Nonspecific antibody binding sites were blocked by overnight incubation at 4°C with PBS, 10% goat serum, and 1% bovine serum albumin. To label plasma membranes, cells were incubated with streptavidin conjugated by Alexa 647 (1:500 dilution in PBS; Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature. To detect nectin-1, the permeabilized cells were labeled with mouse ascites extract containing monoclonal antibodies CK41 and CK6, a gift from R. Eisenberg, G. Cohen, and C. Krummenacher (University of Pennsylvania), followed by the addition of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat antimouse secondary antibody (1:500 dilution; Invitrogen, Inc.). To detect tight junctions or adherens junctions, the cells were incubated with mouse anti-ZO-1 (zonula occludens protein 1) or mouse anti-desmoglein-1 (1:500; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Alexa Fluor 350 secondary antibody. To detect phosphorylated FAK following infection, the infected cells were incubated with monoclonal anti-pFAK (1:500; Upstate, Lake Placid, NY) and Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody. Nuclei were detected by staining with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole nucleic acid stain (DAPI) (Molecular Probes, Inc.). The Transwell membranes were excised from the culture inserts and mounted to glass slides using the ProLong Gold Antifade reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California). Slides were examined using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope fitted with a ×100 objective. Image analysis and subcellular colocalization were generated and analyzed using the LSM confocal software package. Quantification of pixel intensity was performed on axial images with NIH Image J densitometric software.

Binding assays.

Cells were grown on Transwells to confluence, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, and exposed to serial dilutions of purified HSV-2 (G) for 2 h at 37°C from either the apical or inverted basolateral surfaces. Unbound virus was removed by washing the cells three times and the cell-bound virus quantified by preparing cell lysates and subjecting the lysates to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting for gD as previously described (5). Blots were scanned and relative amounts of bound virus compared.

Nuclear transport of VP-16.

Cells were grown on Transwells to confluence and infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of ∼10 PFU/cell from either the apical or inverted basolateral surfaces for 1 h at 37°C. The cells were washed and treated with citrate buffer (pH 3.0) for 1 min to inactivate any bound but nonpenetrant virus and overlaid with fresh medium. Transport of VP16 to the nucleus was detected 1 h post-citrate treatment by preparing nuclear extracts for SDS-PAGE and Western blots (4). Blots were probed with mouse anti-VP16 (final concentration, 1:500; sc7545; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse immunoglobulin G (final concentration, 1:1,000; 401215; Calbiochem) for 1 h. Blots of cell lysates were also probed with anti β-actin MAb (A5441; Sigma-Aldrich) to control for protein loading.

Disruption of tight junctions.

Cells were grown to confluence, and TER was measured prior to and following treatment for 30 min with 8 mM EGTA in PBS or, as a control, PBS containing 0.5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM CaCl2. The cells were washed thrice with PBS and then exposed to HSV-2 (G) at either the apical or inverted basolateral surfaces and plaque formation or GFP expression monitored.

Transfection with siRNA.

Caco2 cells grown in Transwell were transfected with small interfering RNA (siRNA) designed to interfere with nectin-1 (GGAGGUCAAUAUCAGAA; D-001206; Dharmacon, Inc.) or nonspecific siRNA (D-002060120; Dharmacon Inc.) at a concentration of 300 pM per well. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cells were infected with HSV-2 (G) or K26GFP as detailed above.

Detection of FAK phosphorylation by immunoblotting.

Cells were grown on Transwells and preincubated with serum-free medium for 12 h before the apical or inverted basolateral membranes were infected. Cell lysates were prepared 10 or 30 min postinfection, and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to membranes for immunoblotting. Membranes were incubated with a 1:500 dilution of monoclonal anti-phospho-Tyr397 FAK antibody, which recognizes the tyrosine autophosphorylation site at position 397 of FAK (Pharmagen, San Diego, CA). The membranes were then stripped and reincubated with a 1:1,000 dilution of mouse anti-FAK MAb (Upstate, NY), which recognizes total FAK. Blots were scanned and analyzed using the GELDOC 2000 system.

Statistical analysis.

GraphPad Prism version 4 (San Diego, CA) was used for statistical analysis. Differences in plaque assay results were compared using one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's posttest to compare groups. Pixel intensities were compared using unpaired two-tailed t tests.

RESULTS

HSV preferentially infects apical surfaces of polarized epithelial cells.

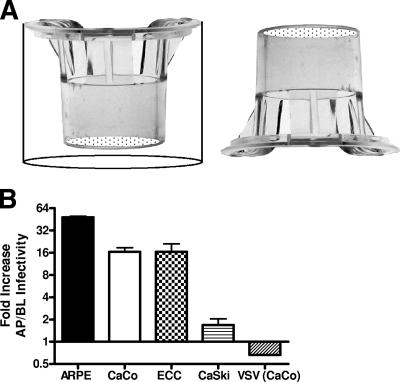

Cells were grown on Transwells and integrity of tight junctions monitored by measuring TER. Serial dilutions of virus (range, 0.001 to 100 PFU/cell) were applied directly to the apical or inverted basolateral surfaces of ARPE, CaCo-2, ECC-1, or CaSki cells (Fig. 1A). After incubation for 1 h at 37°C, the viral inoculum was removed by gently washing the inserts three times with PBS. The inverted inserts were turned upright, and both sets (apical and basolateral surface infected inserts) were overlaid with fresh medium and allowed to incubate for 48 h. HSV plaques were counted after immunoassay, and VSV plaques were counted after Geimsa staining. Only wells in which the number of PFU ranged between 25 and 200 were used to calculate the n-fold difference in susceptibility. Under these experimental conditions, there was little difference in susceptibility to HSV in the less-polarized CaSki cells (∼2-fold), but in the more polarized epithelia, the cells were 16- to 50-fold more susceptible to HSV-2 infection at the apical surfaces than at the basolateral surfaces (Fig. 1B). Similar results were obtained with several different strains of both HSV-1 and HSV-2 (data not shown). In contrast, VSV showed similar infection at the apical and basolateral membranes on polarized CaCo-2 cells.

FIG. 1.

HSV preferentially infects AP surface of polarized epithelial cells. (A) Diagram demonstrating that cells were infected either at the apical (left) or inverted basolateral (right) surface by exposing each surface to 100 μl of virus for 1 h. (B) To compare susceptibility to HSV infection, cells were exposed at either the apical (AP) or inverted basolateral (BL) membranes to serial dilutions of HSV-2 (G) or VSV as indicated. Plaques were counted 48 h p.i. and the viral titer determined. Results are presented as the n-fold difference in viral titer following apical versus basolateral exposure to virus and are means ± standard errors obtained from at least three independent experiments. Only wells in which the number of plaques ranged between 25 and 200 were used to calculate the n-fold difference in viral titer. Similar results were obtained with HSV-1 (KVP26-GFP) (not shown).

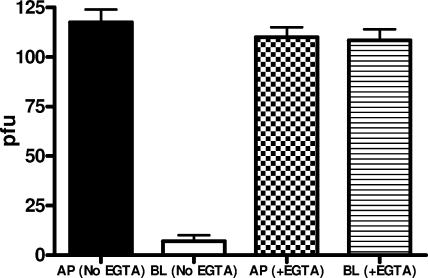

To determine whether disruption of the tight junctions alters the polarity of HSV entry, cells were grown on Transwells and treated with 8 mM EGTA for 30 min or PBS containing 0.5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM CaCl2; the TER fell to baseline after EGTA treatment but not in cells treated with control buffer. Cells were then exposed to HSV-1 or HSV-2 at the apical or inverted basolateral membranes in the presence of Ca2+-free medium, and infection was monitored by counting plaques 48 h p.i. Representative results with ECC-1 cells and HSV-2 demonstrate that disruption of the tight junctions had little effect on apical infection but restored susceptibility at the basolateral surface to levels similar to that observed at the apical membrane (Fig. 2) (P < 0.001). Similar results were obtained with the other polarized cells and with HSV-1. This observation suggests that disruption of the tight junctions exposes a previously inaccessible cellular component required for efficient entry at the basolateral surface.

FIG. 2.

Disruption of junctions overcomes restriction to HSV infection at the basolateral surface: polarized cells were treated with 8 mM EGTA for 30 min or control buffer (PBS containing 0.5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM CaCl2); the TER fell to baseline levels after EGTA treatment. Cells were then exposed to HSV-2 (G) at the apical (AP) or inverted basolateral (BL) membrane in the presence of Ca2+-free medium, and infection was monitored by counting plaques 48 h p.i. Representative results showing numbers of PFU/insert formed following treatment with EGTA or control buffer on ECC-1 cells are shown (means ± standard errors).

Differences in infectivity map to a step prior to nuclear transport.

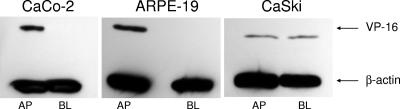

Presumably the differences in infectivity at the apical and basolateral surfaces must be determined by steps prior to delivery of the viral DNA to the nucleus. To confirm this, two additional approaches were adopted. First, we took advantage of the viral variant, K26GFP, an HSV-1 virus that expresses a GFP-VP26 fusion protein. Cells were grown on Transwells, infected at the apical or inverted basolateral surfaces, fixed and stained with EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-Biotin to detect cellular plasma membranes and DAPI to detect nuclei at different times p.i., and viewed by confocal microscopy. Viral GFP was detected in the cytoplasm of most of the cells infected from the apical but not the basolateral surfaces as early as 1 h p.i., consistent with a relative block in infection at the basolateral surface. In contrast, similar amounts of viral GFP were detected if the cells were first treated with EGTA to disrupt the tight junctions (data not shown). Second, the nuclear transport of VP16, a tegument protein, following apical or inverted basolateral exposure to HSV-2 was compared by preparing Western blots of nuclear extracts. Results indicate a basolateral restriction on VP16 transport in CaCo-2 and ARPE-19 but not CaSki cells, which is consistent with the plaque assay results (Fig. 3). Together these studies suggest that the reduced susceptibility to HSV invasion reflects a block at a step prior to nuclear transport of capsids and tegument proteins.

FIG. 3.

Nuclear transport of VP16 is readily detected following apical but not basolateral exposure to HSV-2 (G). CaCo-2, ARPE, or CaSki cells were exposed to HSV-2 (G), and 1 to h p.i., nuclear extracts were prepared and analyzed for the presence of the viral tegument protein VP16 by Western blotting or for β-actin to control for protein loading. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

The increased susceptibility to apical entry correlates with access to nectin coreceptors.

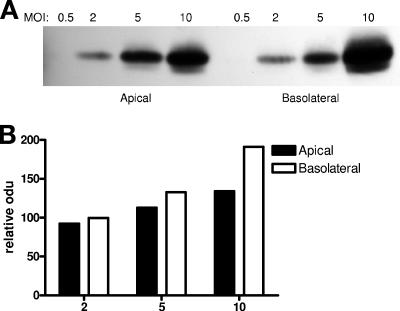

Enhanced susceptibility to HSV at the apical membrane might reflect increased receptor or coreceptor access or an increased ability to activate the signaling pathways required for fusion and/or nuclear transport (4, 6). To begin to explore these possibilities, the specific binding activity (particles bound/cell) following apical or basolateral exposure was compared. CaCo-2 cells were grown on Transwells, fixed, and exposed to serial dilutions of purified HSV-2 (G) for 1 h at 37°C from either the apical or inverted basolateral surfaces. After the cells were washed to remove unbound virus, the cell-bound virus was compared by preparing cell lysates, subjecting the lysates to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting for gD as previously described (Fig. 4A) (5). Gels were scanned and relative amounts of bound virus compared (Fig. 4B). The binding gels demonstrate no reduction in binding at the basolateral surface, and at a MOI of 10 PFU/cell, more virus bound to the basolateral surface. This could reflect the increased surface area at the basolateral membrane or could be explained by preferential sorting of heparan sulfate proteoglycans to the basolateral membrane of polarized epithelia as previously described (3).

FIG. 4.

There is no reduction in viral binding at the basolateral membrane. Cells were grown on Transwells, fixed, and exposed to serial dilutions of HSV-2 (G) for 1 h at 37°C from either the apical or inverted basolateral surface. Bound virus was detected by analyzing Western blots of cell lysates for gD. A representative blot showing results obtained with CaCo-2 cells is shown in panel A; the blots were scanned and relative amounts of bound virus compared by optical density (odu) (panel B).

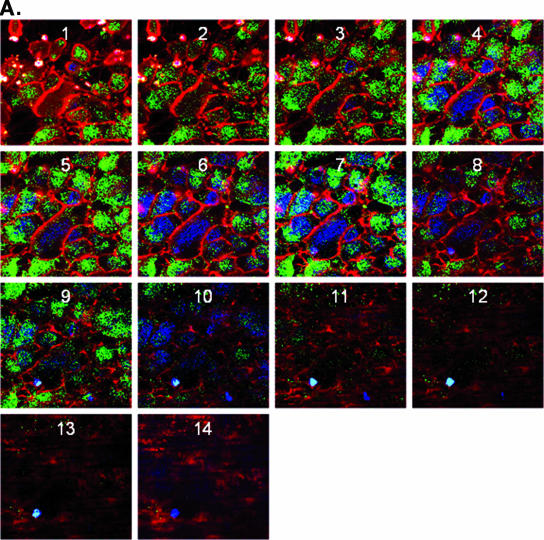

To determine if the preferential infection at the apical surface reflects differences in coreceptor expression, confocal microscopy studies were conducted using MAbs specific for nectin-1, the predominant coreceptor on human epithelial cells (21). Axial sections demonstrated almost exclusive bias toward expression of nectin at the apical cell surface (Fig. 5A) (39). To further localize nectin-1 in these human epithelial cells, additional confocal images were examined after staining also for either a representative tight junction protein, ZO-1, or an adherens junction protein, desmoglein-1. Both ZO-1 and desmoglein-1 showed preferential sorting towards the apical membrane and overlapped with nectin-1 expression (Fig. 5B and C) (16). Treatment of cells with EGTA, which disrupts junctions, led to redistribution of nectin-1 and desmoglein-1 such that there no longer appeared to be any bias towards apical expression (Fig. 5D). A similar redistribution of ZO-1 was also observed (data not shown). The observed redistribution is consistent with the loss of preferential apical infection following EGTA treatment (Fig. 2).

FIG. 5.

Localization of nectin-1 expression by confocal microscopy. (A) CaCo-2 cells were grown on Transwells and stained with EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-Biotin to detect cellular plasma membranes (red). After labeling of the plasma membranes, the cells were permeabilized and incubated overnight at 4°C with PBS-10% goat serum-1% bovine serum albumin to block nonspecific binding sites. In panel A, the nuclei were detected by staining with DAPI (blue), and nectin-1 was visualized by labeling with monoclonal antibodies CK41 and CK6 (green). Successive axial sections from the apical to the basal membrane are representative of at least five independent experiments. Panel B shows a representative Z-section image of polarized CaCo-2 cells stained for plasma membrane (red), nectin-1 (green), and a tight junction protein, ZO-1 (blue), and panel C shows a representative Z-section stained for plasma membrane (red), nectin-1 (green), and an adherens junction protein, desmoglein-1 (blue) (magnification, ×100). Results are representative of those obtained in three independent experiments. Panel D shows pixel intensity results obtained for successive axial sections from the apical to the basal membrane for nectin-1 and desmoglein-1 in the presence of control PBS buffer (left) or following disruption of junctions with EGTA (right).

Transfection with nectin-specific siRNA reduces susceptibility to apical but not basolateral infection.

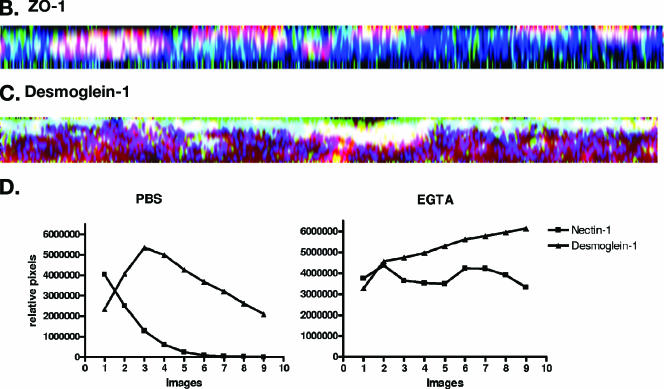

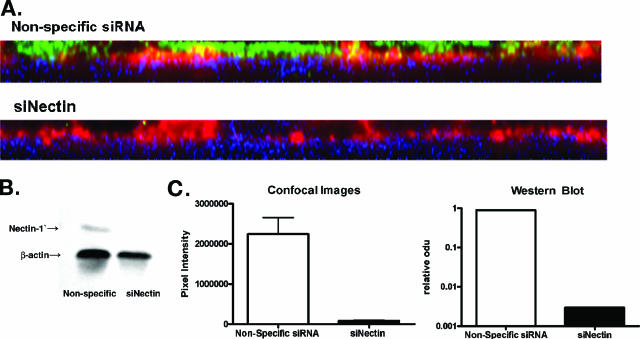

To explore whether the differences in nectin expression correlated with differences in susceptibility to HSV infection, cells were transfected with either siRNA specific for nectin or a nonspecific siRNA, and the impact on protein expression and susceptibility to HSV infection at the two surfaces was compared. Transfection with nectin sequence-specific siRNA but not nonspecific siRNA reduced nectin expression at the apical membrane by greater than 96% (P = 0.0275) (Fig. 6A and C). A similar reduction in nectin expression was observed by preparing a Western blot of cell lysates (Fig. 6B and C). Transfection with nectin siRNA significantly reduced HSV infection at both the apical and basolateral surfaces of the nonpolarized CaSki cells. In contrast, only apical infection was reduced following transfection with nectin siRNA on polarized ECC-1 or CaCo-2 cells (Fig. 7A). This observation suggests that nectin-1 may not be the predominant coreceptor for basolateral infection on these polarized epithelial cells. Notably, there was an unexplained increase in infection at the basolateral surfaces of CaCo-2, but not ECC-1, cells following transfection with nectin-specific siRNA. This could not be attributed to disruption of tight junctions, since transfection with nectin-specific siRNA reduced the TER by only ∼10% (data not shown). Possibly the coreceptors used by HSV for basolateral entry are redistributed or are more accessible following transfection with the nectin-specific siRNA. Consistent with this notion, a redistribution of ZO-1 was observed following transfection of cells with nectin-specific siRNA (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 6.

Transfection with nectin-specific siRNA (siNectin) reduces gene expression. CaCo-2 cells were transfected with nectin-specific or control siRNA and then 24 h later were examined by confocal microscopy for nectin expression as shown in panel A (nectin-1, green; plasma membrane, red; nuclei, blue) or by preparing Western blots (panel B). Panel C shows pixel intensity and the results of scanning blots for nectin expression following transfections.

FIG. 7.

Transfection with nectin-specific siRNA reduces infection at the apical but not the basolateral membrane and triggers a redistribution of ZO-1. To assess the impact of the transfections on susceptibility to HSV, ECC-1, CaCo-2, or CaSki cells were transfected and 24 h later were infected with HSV-2 (G). Plaques were counted after immunostaining 48 h p.i.; results are means ± standard errors obtained from three independent experiments and are presented as PFU formed following transfection with nectin-specific siRNA as a percentage of PFU formed following transfection with nonspecific siRNA. A similar reduction in apical infection was observed with HSV-1 (not shown). To examine whether there was a redistribution of cellular proteins following transfection, CaCo-2 cells were transfected with nectin-specific or control siRNA and then 24 h later examined by confocal microscopy for nectin expression and ZO-1. Panel B shows pixel intensity results obtained for successive axial sections from the apical to the basal membrane.

HSV induces FAK phosphorylation pathways following apical but not basolateral infection.

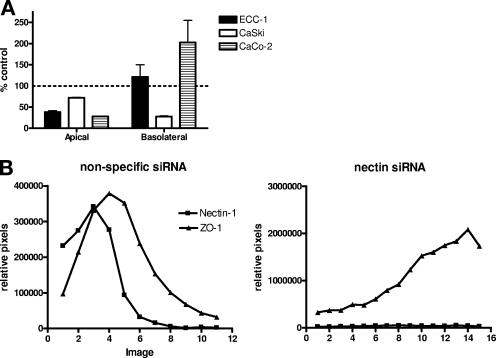

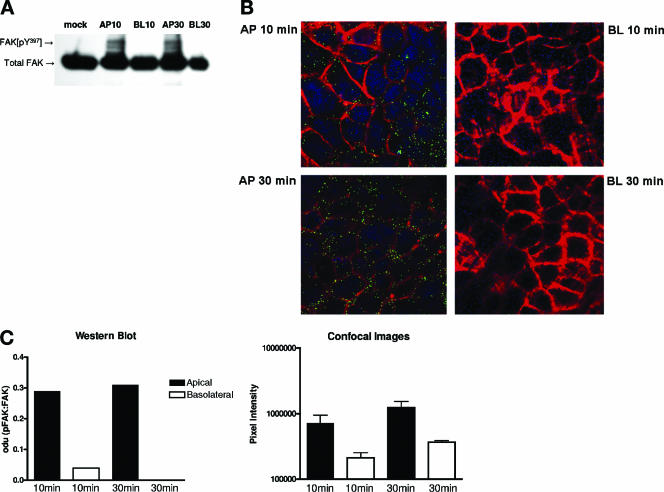

HSV entry into nonpolarized human epithelial cells is associated with activation of a cascade of cellular signaling events including the phosphorylation of FAK (4, 6). To examine the activation of signaling pathways following infection of polarized epithelial cells, CaCo-2 cells grown on Transwells were serum starved overnight and exposed to HSV-2 from the apical or inverted basolateral surfaces. At 10 or 30 min p.i., the cells were fixed and examined for the presence of phosphorylated FAK either by preparing Western blots (Fig. 8A) or by confocal microscopy (Fig. 8B). Images and gels were scanned (Fig. 8C). HSV-2 induces FAK phosphorylation in cells infected from the apical but not the basolateral surfaces. This may reflect the reduced susceptibility to HSV because of inaccessibility to nectin. However, the possibility that the signaling pathways themselves are polarized cannot be excluded and requires further study.

FIG. 8.

HSV induces phosphorylation of FAK following apical but not basolateral exposure. Cells were serum starved overnight and mock infected or infected with HSV-2 (G) (MOI, ∼1 PFU/cell) from the apical (AP) or inverted basolateral (BL) surfaces, and at 10 or 30 min postexposure, cells were fixed and stained for phosphorylated FAK by preparation of Western blots (panel A) or by confocal microscopy (panel B). The images are representative of results obtained from three independent experiments. Panel C shows mean optical density units (odu) from scanning a representative blot (left) or mean pixel intensity (right) results obtained from scanning multiple images (means ± standard errors).

DISCUSSION

HSV-1 and HSV-2 are primarily transmitted across mucosal surfaces and infrequently are a consequence of systemic infection. Consistent with this route of transmission, we found that both serotypes preferentially infect the apical surfaces of the human epithelial cells examined in these studies. Susceptibility to infection at the apical surface is linked to expression of the gD coreceptor, nectin-1 (or HveC). Confocal microscopy studies revealed that nectin-1 was distributed towards the apical surface of these human epithelial cells and its highest intensity overlapped with the adherens junction protein, desmoglein-1, and with the tight junction protein, ZO-1. However, little or no nectin could be identified at the basolateral membrane. These findings are consistent with those of recently published studies with both cell culture and murine models (12, 27, 41, 42). Linehan and colleagues found that at diestrus, when mice are most susceptible to HSV infection, nectin-1 was found primarily at the luminal layer of cells in the vaginal epithelium, localized mostly to junctions (24).

Notably, results of these studies differ markedly from those obtained with MDCK cells, the cell type used in most prior studies of the polarity of HSV infection. Differences may reflect the difference in species, relative nonsusceptibility of MDCK cells to HSV compared to human epithelial cells, and experimental design. In most MDCK studies, HSV was found to preferentially infect the basolateral surface. Disruption of the adherens junctions of MDCK cells was required to liberate nectin-1 (26, 46). We found that disruption of the tight junctions had little or no effect on apical infection but significantly enhanced basolateral infection. Confocal studies suggest that disruption of the tight junctions led to redistribution of nectin-1 (as well as desmoglein and ZO-1), which may contribute to the observed increase in susceptibility at the basolateral surface. If results obtained with these human cell lines in vitro reflect what happens in vivo, HSV might readily infect intact human epithelial cells, presuming the virus has access to nectin-1 at the apical surface. It should be noted that these studies did not examine terminally differentiated keratinocytes, which have previously been shown to express little nectin-1 in human tissue biopsy samples (24). Thus, disruption of the superficial layer of keratinocytes may be required for the virus to have access to the apical membrane of epithelial cells.

The observation that transfection of human epithelial cells with siRNA specific for nectin-1 led to a significant reduction in viral infection at the apical surface further supports the predominant role of nectin-1 as a coreceptor for infection of human epithelial cells. These observations complement those with the murine model, where pretreatment of virus with recombinant nectin-1 impeded infection (24). Whether the residual apical infection observed following transfection with nectin siRNA reflects incomplete silencing or use of alternative coreceptors by the virus requires further study. In ongoing studies, we are optimizing experimental conditions to maximize the extent and duration of gene silencing by nectin-specific siRNA.

Notably, transfection with nectin-specific siRNA resulted in no reduction in HSV infection at the basolateral surfaces of the polarized epithelial cells but did reduce basolateral infection in CaSki cells. Possibly, infection at the basolateral membrane of polarized epithelia occurs independently of nectin-1. The virus may use other coreceptors to infect at the basolateral surface. These alternative coreceptors either are not present in sufficient concentration, have a weaker affinity for gD, or are not capable of activating the requisite signaling pathways, such as the FAK pathway, as efficiently, thus contributing to the reduced susceptibility to HSV at the basolateral membrane. There was a modest increase in basolateral infection in the CaCo-2 cells following transfection with nectin-specific siRNA. This might reflect redistribution of cellular components leading to increased access to an alternative coreceptor. Consistent with this notion, we observed changes in the distribution of ZO-1 following transfection with nectin-specific siRNA. No substantial reduction in TER following transfection was observed (TER fell by ∼10%); thus, it seems unlikely that the increase in susceptibility to HSV at the basolateral membranes reflects a loss of tight junctions. However, TER measurements are not necessarily fully reflective of functional tight junctions, nor do they correlate with adherens junction formation. A recent study found a discrepancy between TER, barrier function, and adherens junction formation in ARPE cells (25). Of note, we found that the ARPE cells displayed the lowest TER among the polarized cells studied yet were the most polarized with respect to susceptibility to HSV infection (Fig. 1B).

In addition to nectin itself, cellular signaling pathways, such as Ca2+ signaling pathways, important for viral penetration, and FAK signaling pathways, important in nuclear transport, may be preferentially sorted to the apical membrane (4, 6). Activation of Ca2+ signaling pathways is influenced by cell polarity (1, 23). For example, the inositol-triphosphate (IP3)-mediated release of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ occurs at the apical poles of pancreatic acinar cells and hepatocytes. The Ca2+ release channels in the endoplasmic reticulum are clustered in the apical pole, and by immunochemistry, IP3 receptors are detected in the apical region in these cells (22, 23, 29). Studies are ongoing that examine the subcellular localization of the IP3 receptors, which also may contribute to the difference in susceptibility to HSV infection at the apical and basolateral membranes.

A recent study demonstrated a functional association between nectin-1 and FAK signaling. Nectin-1 colocalized with integrin α(v)β3 at cell-cell adhesion sites, and this interaction was necessary for activation of signaling pathways, including FAK phosphorylation (32). Although precisely how HSV triggers FAK phosphorylation is not yet fully understood, the observation that FAK phosphorylation could be detected only following apical exposure to virus in the polarized cells examined in these studies is consistent with an association between nectin and FAK and the possibility that FAK also polarizes apically.

Together, these findings suggest that nectin-1 or its ligand, gD, should be considered as potential targets for novel preventative strategies. In preliminary studies we found that intravaginal application of liposomal complexes of nectin-1 siRNA induced gene-specific silencing in a murine model (B. Galen, B. Ramratnam and B. Herold, unpublished data). Obstacles to the success of this strategy include effectively delivering siRNA to appropriate cells in vivo, maintaining an effective level of gene silencing over a long period, and preventing the selection for resistant viral variants. Most importantly, gene silencing must have no deleterious impact on the host. This may be easier to achieve if the siRNA is delivered topically rather than systemically. Limited genetic studies have mapped the cleft lip/palate-ectodermal dysplasia syndrome (Zlotogora-Ogur syndrome and Margarita Island ectodermal dysplasia) to the gene for nectin-1, PVRL1 (40). No other human diseases have been described in association with nectin-1 mutations, and the precise role of nectin-1 at mucosal surfaces is not known. Notably, although silencing of CCR5, one of the major coreceptors for HIV infection, has been extensively evaluated as a strategy to prevent HIV infection, a recent study found that CCR5Δ32, a defective CCR5 allele associated with protection against HIV infection, was associated with an increased risk for West Nile virus infection (9, 15). Thus, the impact of gene silencing strategies that target host proteins on susceptibility to disease must be carefully elucidated before such approaches are advanced.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prashant Desai, Johns Hopkins University, for the generous gift of the K26GFP virus and Robert F. Hennigan and Ramona Hug of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Microscopy Shared Research Facility for advice and assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, AI061679 and HD43733, to B.C.H.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 September 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashby, M. C., and A. V. Tepikin. 2002. Polarized calcium and calmodulin signaling in secretory epithelia. Physiol. Rev. 82:701-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blau, D. M., and R. W. Compans. 1995. Entry and release of measles virus are polarized in epithelial cells. Virology 210:91-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caplan, M. J., J. L. Stow, A. P. Newman, J. Madri, H. C. Anderson, M. G. Farquhar, G. E. Palade, and J. D. Jamieson. 1987. Dependence on pH of polarized sorting of secreted proteins. Nature 329:632-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheshenko, N., B. Del Rosario, C. Woda, D. Marcellino, L. M. Satlin, and B. C. Herold. 2003. Herpes simplex virus triggers activation of calcium-signaling pathways. J. Cell Biol. 163:283-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheshenko, N., and B. C. Herold. 2002. Glycoprotein B plays a predominant role in mediating herpes simplex virus type 2 attachment and is required for entry and cell-to-cell spread. J. Gen. Virol. 83:2247-2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheshenko, N., W. Liu, L. M. Satlin, and B. C. Herold. 2005. Focal adhesion kinase plays a pivotal role in herpes simplex virus entry. J. Biol. Chem. 280:31116-31125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clayson, E. T., and R. W. Compans. 1988. Entry of simian virus 40 is restricted to apical surfaces of polarized epithelial cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:3391-3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desai, P., and S. Person. 1998. Incorporation of the green fluorescent protein into the herpes simplex virus type 1 capsid. J. Virol. 72:7563-7568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diamond, M. S., and R. S. Klein. 2006. A genetic basis for human susceptibility to West Nile virus. Trends Microbiol. 14:287-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duan, D., Y. Yue, Z. Yan, P. B. McCray, Jr., and J. F. Engelhardt. 1998. Polarity influences the efficiency of recombinant adenoassociated virus infection in differentiated airway epithelia. Hum. Gene Ther. 9:2761-2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duan, D., Y. Yue, Z. Yan, J. Yang, and J. F. Engelhardt. 2000. Endosomal processing limits gene transfer to polarized airway epithelia by adeno-associated virus. J. Clin. Investig. 105:1573-1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuhara, A., K. Irie, A. Yamada, T. Katata, T. Honda, K. Shimizu, H. Nakanishi, and Y. Takai. 2002. Role of nectin in organization of tight junctions in epithelial cells. Genes Cells 7:1059-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuller, S., C. H. von Bonsdorff, and K. Simons. 1984. Vesicular stomatitis virus infects and matures only through the basolateral surface of the polarized epithelial cell line, MDCK. Cell 38:65-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuller, S. D., C. H. von Bonsdorff, and K. Simons. 1985. Cell surface influenza haemagglutinin can mediate infection by other animal viruses. EMBO J. 4:2475-2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glass, W. G., D. H. McDermott, J. K. Lim, S. Lekhong, S. F. Yu, W. A. Frank, J. Pape, R. C. Cheshier, and P. M. Murphy. 2006. CCR5 deficiency increases risk of symptomatic West Nile virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 203:35-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez-Mariscal, L., M. C. Namorado, D. Martin, J. Luna, L. Alarcon, S. Islas, L. Valencia, P. Muriel, L. Ponce, and J. L. Reyes. 2000. Tight junction proteins ZO-1, ZO-2, and occludin along isolated renal tubules. Kidney Int. 57:2386-2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffiths, A., S. Renfrey, and T. Minson. 1998. Glycoprotein C-deficient mutants of two strains of herpes simplex virus type 1 exhibit unaltered adsorption characteristics on polarized or non-polarized cells. J. Gen. Virol. 79:807-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Handler, J. S., A. S. Preston, and R. E. Steele. 1984. Factors affecting the differentiation of epithelial transport and responsiveness to hormones. Fed. Proc. 43:2221-2224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayashi, K. 1995. Role of tight junctions of polarized epithelial MDCK cells in the replication of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Med. Virol. 47:323-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herold, B. C., D. WuDunn, N. Soltys, and P. G. Spear. 1991. Glycoprotein C of herpes simplex virus type 1 plays a principal role in the adsorption of virus to cells and in infectivity. J. Virol. 65:1090-1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krummenacher, C., I. Baribaud, R. J. Eisenberg, and G. H. Cohen. 2003. Cellular localization of nectin-1 and glycoprotein D during herpes simplex virus infection. J. Virol. 77:8985-8999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, M. G., X. Xu, W. Zeng, J. Diaz, R. J. Wojcikiewicz, T. H. Kuo, F. Wuytack, L. Racymaekers, and S. Muallem. 1997. Polarized expression of Ca2+ channels in pancreatic and salivary gland cells. Correlation with initiation and propagation of [Ca2+]i waves. J. Biol. Chem. 272:15765-15770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leite, M. F., A. D. Burgstahler, and M. H. Nathanson. 2002. Ca2+ waves require sequential activation of inositol trisphosphate receptors and ryanodine receptors in pancreatic acini. Gastroenterology 122:415-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linehan, M. M., S. Richman, C. Krummenacher, R. J. Eisenberg, G. H. Cohen, and A. Iwasaki. 2004. In vivo role of nectin-1 in entry of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and HSV-2 through the vaginal mucosa. J. Virol. 78:2530-2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo, Y., Y. Zhuo, M. Fukuhara, and L. J. Rizzolo. 2006. Effects of culture conditions on heterogeneity and the apical junctional complex of the ARPE-19 cell line. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47:3644-3655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marozin, S., U. Prank, and B. Sodeik. 2004. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection of polarized epithelial cells requires microtubules and access to receptors present at cell-cell contact sites. J. Gen. Virol. 85:775-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsushima, H., A. Utani, H. Endo, H. Matsuura, M. Kakuta, Y. Nakamura, N. Matsuyoshi, C. Matsui, H. Nakanishi, Y. Takai, and H. Shinkai. 2003. The expression of nectin-1alpha in normal human skin and various skin tumours. Br. J. Dermatol. 148:755-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milne, R. S., A. V. Nicola, J. C. Whitbeck, R. J. Eisenberg, and G. H. Cohen. 2005. Glycoprotein D receptor-dependent, low-pH-independent endocytic entry of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 79:6655-6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nathanson, M. H., M. B. Fallon, P. J. Padfield, and A. R. Maranto. 1994. Localization of the type 3 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in the Ca2+ wave trigger zone of pancreatic acinar cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269:4693-4696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicola, A. V., and S. E. Straus. 2004. Cellular and viral requirements for rapid endocytic entry of herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 78:7508-7517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rousset, M. 1986. The human colon carcinoma cell lines HT-29 and Caco-2: two in vitro models for the study of intestinal differentiation. Biochimie 68:1035-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakamoto, Y., H. Ogita, T. Hirota, T. Kawakatsu, T. Fukuyama, M. Yasumi, N. Kanzaki, M. Ozaki, and Y. Takai. 2006. Interaction of integrin alpha(v)beta3 with nectin. Implication in cross-talk between cell-matrix and cell-cell junctions. J. Biol. Chem. 281:19631-19644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaefer, T. M., K. Desouza, J. V. Fahey, K. W. Beagley, and C. R. Wira. 2004. Toll-like receptor (TLR) expression and TLR-mediated cytokine/chemokine production by human uterine epithelial cells. Immunology 112:428-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schelhaas, M., M. Jansen, I. Haase, and D. Knebel-Morsdorf. 2003. Herpes simplex virus type 1 exhibits a tropism for basal entry in polarized epithelial cells. J. Gen. Virol. 84:2473-2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sears, A. E., B. S. McGwire, and B. Roizman. 1991. Infection of polarized MDCK cells with herpes simplex virus 1: two asymmetrically distributed cell receptors interact with different viral proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:5087-5091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shukla, D., J. Liu, P. Blaiklock, N. W. Shworak, X. Bai, J. D. Esko, G. H. Cohen, R. J. Eisenberg, R. D. Rosenberg, and P. G. Spear. 1999. A novel role for 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate in herpes simplex virus 1 entry. Cell 99:13-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spear, P. G. 2004. Herpes simplex virus: receptors and ligands for cell entry. Cell Microbiol. 6:401-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spear, P. G., and R. Longnecker. 2003. Herpesvirus entry: an update. J. Virol. 77:10179-10185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Subramanian, V. S., J. S. Marchant, and H. M. Said. 2006. Targeting and trafficking of the human thiamine transporter-2 in epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 281:5233-5245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki, K., D. Hu, T. Bustos, J. Zlotogora, A. Richieri-Costa, J. A. Helms, and R. A. Spritz. 2000. Mutations of PVRL1, encoding a cell-cell adhesion molecule/herpesvirus receptor, in cleft lip/palate-ectodermal dysplasia. Nat. Genet. 25:427-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi, K., H. Nakanishi, M. Miyahara, K. Mandai, K. Satoh, A. Satoh, H. Nishioka, J. Aoki, A. Nomoto, A. Mizoguchi, and Y. Takai. 1999. Nectin/PRR: an immunoglobulin-like cell adhesion molecule recruited to cadherin-based adherens junctions through interaction with Afadin, a PDZ domain-containing protein. J. Cell Biol. 145:539-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takai, Y., and H. Nakanishi. 2003. Nectin and afadin: novel organizers of intercellular junctions. J. Cell Sci. 116:17-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Topp, K. S., A. L. Rothman, and J. H. Lavail. 1997. Herpes virus infection of RPE and MDCK cells: polarity of infection. Exp. Eye Res. 64:343-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tran, L. C., J. M. Kissner, L. E. Westerman, and A. E. Sears. 2000. A herpes simplex virus 1 recombinant lacking the glycoprotein G coding sequences is defective in entry through apical surfaces of polarized epithelial cells in culture and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1818-1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Bonsdorff, C. H., S. D. Fuller, and K. Simons. 1985. Apical and basolateral endocytosis in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells grown on nitrocellulose filters. EMBO J. 4:2781-2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoon, M., and P. G. Spear. 2002. Disruption of adherens junctions liberates nectin-1 to serve as receptor for herpes simplex virus and pseudorabies virus entry. J. Virol. 76:7203-7208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zabner, J., P. Freimuth, A. Puga, A. Fabrega, and M. J. Welsh. 1997. Lack of high affinity fiber receptor activity explains the resistance of ciliated airway epithelia to adenovirus infection. J. Clin. Investig. 100:1144-1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zabner, J., M. Seiler, R. Walters, R. M. Kotin, W. Fulgeras, B. L. Davidson, and J. A. Chiorini. 2000. Adeno-associated virus type 5 (AAV5) but not AAV2 binds to the apical surfaces of airway epithelia and facilitates gene transfer. J. Virol. 74:3852-3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang, L., M. E. Peeples, R. C. Boucher, P. L. Collins, and R. J. Pickles. 2002. Respiratory syncytial virus infection of human airway epithelial cells is polarized, specific to ciliated cells, and without obvious cytopathology. J. Virol. 76:5654-5666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]