Abstract

This longitudinal study extended previous work of Wiesner and Capaldi (2003) by examining the validity of differing offending pathways and the prediction from the pathways to substance use and depressive symptoms for 204 young men. Findings from this study indicated good external validity of the offending trajectories. Further, substance use and depressive symptoms in young adulthood (i.e., ages 23-24 through 25-26 years) varied depending on different trajectories of offending from early adolescence to young adulthood (i.e., ages 12-13 through 23-24 years), even after controlling for antisocial propensity, parental criminality, demographic factors, and prior levels of each outcome. Specifically, chronic high-level offenders had higher levels of depressive symptoms and engaged more often in drug use compared with very rare, decreasing low-level, and decreasing high-level offenders. Chronic low-level offenders, in contrast, displayed fewer systematic differences compared with the two decreasing offender groups and the chronic high-level offenders. The findings supported the contention that varying courses of offending may have plausible causal effects on young adult outcomes beyond the effects of an underlying propensity for crime.

Keywords: Offending, trajectories, young adulthood, adjustment, longitudinal

Developmental Trajectories of Offending: Validation and Prediction to Young Adult Alcohol Use, Drug Use, and Depressive Symptoms

The importance of distinguishing various developmental pathways of behavior across the life span has been emphasized for years in developmental psychopathology (e.g., Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000), criminology (e.g., Thornberry, 1997), and life-span developmental psychology (e.g., Elder, 1998). Advancements in statistical methods, semiparametric group-based modeling (Nagin, 1999), and latent growth mixture modeling (LGMM; Muthén & Muthén, 2000; Muthén & Shedden, 1999) have opened new avenues for modeling heterogeneity in developmental trajectories. Several recent studies have focused on identifying subgroups of offenders from childhood through adolescence or young adulthood (e.g., Chung, Hill, Hawkins, Gilchrist, & Nagin, 2002; D'Unger, Land, McCall, & Nagin, 1998; Fergusson, Horwood, & Nagin, 2000; Nagin, Farrington, & Moffitt, 1995), and most have examined risk factors and precursors of differing offending trajectories. Two issues that have received less attention are, first, the external validity of subgroups that are based on self-reported delinquency and, second, patterns of key behaviors that may be outcomes of distinctive offending pathways and whether these can be explained parsimoniously by antisocial propensity or are more consistent with models positing developmental influences of offending behavior on subsequent adjustment. The purpose of the current study was to address these two issues, with arrest records and lifetime diagnoses of antisocial personality disorder in early adulthood examined as validating criteria and with alcohol and drug use and depressive symptoms assessed across a 3-year period in the mid-20s examined as outcomes.

The assumption of differential outcomes of diverse developmental pathways of offending is consistent with both developmental and propensity theories of crime. However, propensity theories (e.g., Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990) claim that individual differences in offending behavior (and trajectories of offending) are mainly of degree, and that they reflect stable individual differences in (lack of) self-control. They further argue that negative consequences and “analogous” problem behaviors, including failures in school and social relationships and drug and alcohol use, are caused by the same underlying propensity factor throughout the life course and, thus, that associations between crime and these behaviors are mainly spurious (see also Evans, Cullen, Burton, Dunaway, & Benson, 1997). In other words, offenders with a developmental pattern of early-onset and chronic offending would be expected to show poorer outcomes as adults (e.g., heavy substance use) because of their poorer self-control, compared to both nonoffenders and offenders with less adverse offending trajectories.

Developmental theories that have predominated in the past decade (e.g., Moffitt, 1993; Patterson & Yoerger, 1993) posit two offending pathways. Early propensity is considered predictive of the first path, namely early-onset and life-course persistent offending, rather than the second, namely late-onset or adolescence-limited offending, but developmental experiences can affect all trajectories. The theories each posit that early-onset offenders are characterized by stable individual characteristics, such as poor self-control, impulsivity, and inability to delay gratification (Moffitt, 1993). However, they differ in such aspects as the degree of emphasis placed on early family risk, parenting, peer influences (e.g., Patterson & Yoerger, 1993), and IQ and neurological impairment (Moffitt, 1993). Developmental theories posit that antisocial behavior that onsets early in childhood is likely to lead to a cascade of secondary problems, including academic failure, involvement with deviant peers, substance abuse, depressive symptoms, health risking sexual behavior, and work failure (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Capaldi, Stoolmiller, Clark, & Owen, 2002; Patterson & Stoolmiller, 1991; Patterson & Yoerger, 1993). For example, youth who show high levels of antisocial behavior in childhood tend to be rejected by normative peers because of their poor social skills and thus become involved with deviant peers at early ages. This, in turn, fosters early initiation of alcohol and drug use (e.g., Dishion, Capaldi, & Yoerger, 1999). Each secondary problem may cause new detrimental consequences or developmental failures in later periods of life (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999). These failures can act as “snares” (Moffitt, Caspi, Dickson, Silva, & Stanton, 1996) that diminish the chances for later success in more conventional arenas. Thus, life-course persistent offenders may become entrapped in a deviant life style. By comparison, late-onset or adolescence-limited offenders (Moffitt, 1993) are posited to initiate offending relatively later in life, show less severe offending (Patterson & Yoerger, 1993), and remain involved in offending for a relatively shorter time period. Hence, their offending and associated developmental failures are less severe, and they have less time to accumulate negative consequences. Within this framework, life-course persistent offenders would be expected to show poorer adjustment in areas such as alcohol and drug use during young adulthood, compared to adolescence-limited offenders.

The processes linking antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms have been further delineated by Capaldi (1991, 1992). According to the organizational model of development (Cicchetti & Schneider-Rosen, 1986), normal or successful development is a cumulative progression of interrelated social, emotional, and cognitive competencies. High levels of conduct problems in childhood interfere with the development of competencies, which, along with associated early-onset offending behavior, may cause a chain reaction of later failures that limit environmental options and make chronically antisocial youth vulnerable to depressive symptoms (Capaldi, 1992). Compared to early-onset offenders, late-onset offenders have a lower risk for developing depressive symptoms because they are less likely to experience failures in multiple domains of life due to their better-developed competencies and less severe and shorter offending careers.

Several variable-oriented longitudinal studies have shown that early conduct problems or juvenile delinquent behavior increase the risk for subsequent problems with alcohol consumption (e.g., Andersson, Mahoney, Wennberg, Kuehlhorn, & Magnusson, 1999; Harford & Muthén, 2000; White, Brick, & Hansell, 1993), drug use (e.g., Pedersen, Mastekaasa, & Wichstrom, 2001; Reebye, Moretti, & Lessard, 1995; Robins & McEvoy, 1990), and depressive symptoms (e.g., Block & Gjerde, 1990; Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Hops, Lewinsohn, Andrews, & Roberts, 1990) in later years. However, person-oriented approaches that focused on studying outcomes of diverse developmental pathways of offending rarely have been used. A long-term study of inner-city London boys revealed that convicted men, desisters, latecomers, and persisters were all significantly more likely than unconvicted men to be heavy drinkers at age 32 years (Farrington, 1989). In addition, convicted men, desisters, and persisters were all significantly more likely to have taken marijuana and other hard drugs than unconvicted men; persisters also were significantly more likely than latecomers to have taken marijuana and other hard drugs at follow-up. A later reanalysis with empirically defined trajectory groups revealed similar findings (Nagin et al., 1995).

Using a priori classification of offender groups, Moffitt et al. (1996) found that boys in the life-course persistent and adolescence-limited groups were more likely to show alcohol dependence and marijuana dependence at age 18 years than those in recovery, abstainer, and unclassified groups. Follow-up data for this cohort at age 26 years indicated that life-course persistent and adolescence-limited offenders were rated by informants as having more alcohol- and drug-related problems and higher levels of depression than unclassified young men. According to informant reports (but not self-reports), life-course persistent offenders showed poorer profiles with regard to alcohol problems and depression at age 26 years, compared to adolescence-limited offenders (Moffitt, Caspi, Harrington, & Milne, 2002).

Another study examined effects of diverse, empirically defined offending trajectories on substance use outcomes, controlling for earlier substance use levels, thus testing whether more severe trajectories were associated with sustained or increased use. Similar analyses were conducted for depression outcomes as well. Hill, Chung, Herrenkohl, and Hawkins (2000) found that low- and high-level chronic property offenders were more likely than nonoffenders to show drug dependency at age 21 years. Effects for alcohol dependency and depression were nonsignificant after controlling for an adolescent proxy of the respective outcome. Chronic violent offenders, on the other hand, were more likely to experience alcohol dependency at age 21 years than were nonoffenders. Effects for drug dependency were nonsignificant after controlling for adolescent drug use, and differences in terms of depressive episodes were not significant at all.

Empirical studies thus offer some support for a linkage between offending trajectories and differential adult outcomes. Differential outcomes in the areas of alcohol and drug use and depressive symptoms are likely to continue during the early adult years for at least two reasons (for more details, see Wiesner, Capaldi, & Patterson, 2003). First, processes of cumulative continuity, developmental failures, and restricted opportunities are hypothesized to continue to be at work for chronic offenders during early adulthood. Secondly, chronic offenders are presumed to be at heightened risk for continued engagement in high-risk contexts, including affiliation with delinquent friends and selection of antisocial intimate partners (Kim & Capaldi, 2004), which again provides positive reinforcement of various deviant behaviors (e.g., drug use) in adulthood. A major issue with developmental theories of offending that have predominated for the past decade is that they posited only two offending trajectories (in addition to rare or nonoffenders). Findings from trajectory modeling studies (e.g., Chung et al., 2002; D'Unger et al., 1998; Fergusson et al., 2000; Sampson & Laub, 2003; Wiesner & Capaldi, 2003) are indicating more than two developmental trajectories of offending and also show other differences from predictions, particularly in the failure to converge on a late-onset group. Thus, these models clearly need extension in addition to further testing of the hypotheses regarding predictors and outcomes of the pathways. Findings from studies using LGMM are converging on a group of high-level chronic offenders, who are similar to the early-onset or life-course persistent group; on a group of low-level chronic offenders, who are not anticipated in developmental theories; and on one or more groups with patterns of decreasing offending by late adolescence or early adulthood, who show some similarities to the late-onset or adolescence-limited group (although there is less evidence of the expected onset in the early to midadolescent period). In addition, sometimes groups with a pattern of late escalating offending have been found (e.g., D'Unger et al., 1998). Finally, there are indications that the chronic group is not life-course persistent in the sense of showing no improvement at all; it appears to desist markedly later in adulthood than other offending trajectories (Sampson & Laub, 2003). Typical of the LGMM studies, Wiesner and Capaldi (2003) found more than two trajectories of offending from early adolescence (ages 12-13 years) through young adulthood (ages 23-24 years). In addition to rare and nonoffenders and chronic high-level (HL) offenders, a group of chronic low-level (LL) offenders was found. Further, two groups of decreasing offenders were found, both of whom decreased to levels similar to the rare or nonoffenders by ages 23-24 years--a group who started at a high level at ages 12-13 years (decreasing high-level (HL) offenders) and a group that started at a level similar to the chronic LL offenders (decreasing low-level (LL) offenders). Thus, the developmental patterns found were more complex than predicted by developmental theories.

Another feature of this literature is that validation issues have often been neglected in studies that have compared empirically defined offender trajectory groups. It is well known that both self-report and official records measures of offending behavior have specific advantages and limitations (e.g., Farrington, Loeber, Stouthamer-Loeber, van Kammen, & Schmidt, 1996; Huizinga & Elliott, 1986; Lauritsen, 1998; Maxfield, Weiler, & Widom, 2000). Therefore, examining arrest records in the juvenile and early adult periods separately for each trajectory of self-reported offending behavior identified in the Wiesner and Capaldi (2003) study provides a valuable external validation criterion. A second possible criterion for this purpose is the diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder. Previous research has indicated that it can serve as an informative external criterion of offending pathways. For example, Moffitt et al. (2002) reported that, compared to unclassified offenders, both life-course persistent and adolescence-limited offenders had elevated rates of past-year antisocial personality disorder at age 26 years. Lifetime diagnoses assessed retrospectively at ages 25-26 years were available in the current study and provide some validation of severity, although not of the developmental patterns themselves. Such a comparison also provides some evidence of the validity of retrospective diagnoses of antisocial personality disorders. In sum, the available studies offer preliminary support for the assumption of differential outcomes of diverse developmental pathways of offending. However, the literature is quite sparse and more studies with independent samples are needed in order to better understand potential effects of sample diversity (e.g., general population versus at-risk sample) and different operationalization of constructs (e.g., offender pathways based on self-reports versus official records). Furthermore, the literature would benefit from more stringent tests of competing explanations of such findings. To the best of our knowledge, findings were rarely controlled for criminal propensity factors. Hence, it is difficult to evaluate whether developmental or propensity theories of crime offer the more adequate explanation of these empirical findings.

Hypotheses

The first purpose of the current study was to further characterize and validate the trajectories of self-reported offending identified in the Wiesner and Capaldi (2003) study. Specifically, we inspected the arrest profiles of the six groups to see how much they converged with self-reported offending profiles. It was predicted that chronic HL offenders would have the highest number of official arrests, including both juvenile and adult arrests. Decreasing LL, rare, and nonoffenders were expected to show indistinguishable and negligible levels of official arrests across the study period. Chronic LL and decreasing HL offenders were predicted to occupy middle ranks between the two extremes, with decreasing HL offenders showing lower levels of arrests during their young adult years than chronic LL offenders (especially after ages 23-24 years, when they had more or less desisted from offending, according to their self-reports). In addition, the distribution of lifetime diagnoses of antisocial personality disorder across the six trajectory groups was inspected. We predicted that young men with lifetime diagnoses of antisocial personality disorder would be overrepresented among chronic HL offenders and underrepresented among rare and nonoffenders.

The second purpose of the current study was to examine predictive effects of the different offending pathways (i.e., from ages 12-13 until ages 23-24 years) identified in the Wiesner and Capaldi (2003) study on young adult alcohol use, drug use, and depressive symptoms (i.e., from ages 23-24 until ages 25-26 years). Congruent with developmental theories, it was expected that the trajectory groups would show significant associations with young adult outcomes after controlling for early antisocial propensity. Two different regression models were performed for each outcome: First, chronic HL offenders were contrasted with each group. Drawing upon the discussed literature, chronic HL offenders were expected to show higher levels of problematic outcomes as young adults, compared to groups with less active and/or more short-lived offending careers (i.e., nonoffenders, rare, decreasing LL, decreasing HL, and chronic LL offenders). Second, chronic LL offenders were contrasted with each decreasing group as well as rare and nonoffenders. This was done in order to test if the second group of chronic offenders, which was not anticipated in the a priori taxonomies discussed above, also showed more problematic outcomes compared to decreasing groups as well as rare and nonoffenders. Importantly, the predictive effects of the different offending pathways were controlled for antisocial propensity, parental arrests, childhood and adolescent proxies of the outcomes, and demographic factors. Parental arrests were included in order to control for effects of offending behavior displayed in the immediate environment (i.e., family) of the young men during their childhood years and possible genetic influences. Antisocial propensity was included in order to help to disentangle effects of an underlying propensity factor from plausible causal effects of the developmental offending trajectories on each outcome.

Method

Sample

The analyses were conducted using data from the Oregon Youth Study (OYS), an ongoing multiagent and multimethod longitudinal study. A sample of boys was selected from schools in the higher crime areas of a medium-sized metropolitan region in the Pacific Northwest. Thus, the boys were considered to be at heightened risk for later delinquency when compared to others in the same region. Of the eligible families, 206 agreed to participate (a 74.4% participation rate). The OYS consists of two successive Grade 4 (ages 9-10 years) cohorts of 102 and 104 boys, recruited in 1983-1984 and 1984-1985 (for details see Capaldi & Patterson, 1987). Subjects were interviewed yearly, with very high retention rates (see Capaldi, Chamberlain, Fetrow, & Wilson, 1997). Subjects who moved were retained in the study, with interviewers traveling to assess them. The two cohorts had very similar demographic characteristics and were combined for the present analyses. The sample was predominantly Caucasian (90%), 75% lower or working class, and over 20% received some form of unemployment or welfare assistance in the first year of the study, a recession year for the local economy (Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992). Two young men who died during the study period were excluded from the analyses. Hence, the final sample size was 204.

Procedures

Assessment on the OYS was yearly, multimethod, and multiagent, including parent and son interviews at the Center (each lasting approximately 1 hour), questionnaires for both parents and the son, telephone interviews that provided multiple samples of recent behaviors (a total of six, 3 days apart), home observations (a total of three 45-minute observations), videotaped interaction tasks, school data (including teacher questionnaires and records data), and court records data. Family consent was mandatory. Participants were paid at each assessment wave.

Measures

Self-reported offending behavior

From ages 12-13 to 25-26 years (i.e., Waves 4 to 17), the young men annually filled out the Elliott Delinquency Scale (Elliot, Ageton, Huizinga, Knowles, & Canter, 1983), a self-report scale that was constructed as a parallel measure to the FBI's Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) arrest measure. Any specific act that involved more than 1% of the UCR-reported juvenile arrests was included in the scale. The offense set covered by the Elliott Delinquency Scale includes all but one UCR Part I offense (homicide was excluded), more than one half of the UCR Part II offenses, and a wide range of other offenses. The young men reported how many times during the past year they committed each of the 45 offenses included in the self-report scale, using an open-ended format. A total score of offending behavior in the past year was formed by summing up the open-ended estimates across 30 selected1 items for each wave separately. The selected items varied in terms of severity and represented various forms of delinquency, including theft, property damage, and violence (e.g., set fire to a building, attacked someone with the idea to seriously hurt him or her, purposely damaged property of others, stole a motor vehicle). Overall, the highest frequencies were reported for relatively less severe offenses by the study participants (e.g., hit someone else, damaged other property, stole something worth less than $5).2 Based on these total annual scores, distinctive offender trajectory groups were identified using the LGMM approach (see below). Prior to use in these analyses, log transformations (a constant was added because some cases had values less than one) were applied to normalize the distributions of the offense scores.

Identification of offender trajectory groups

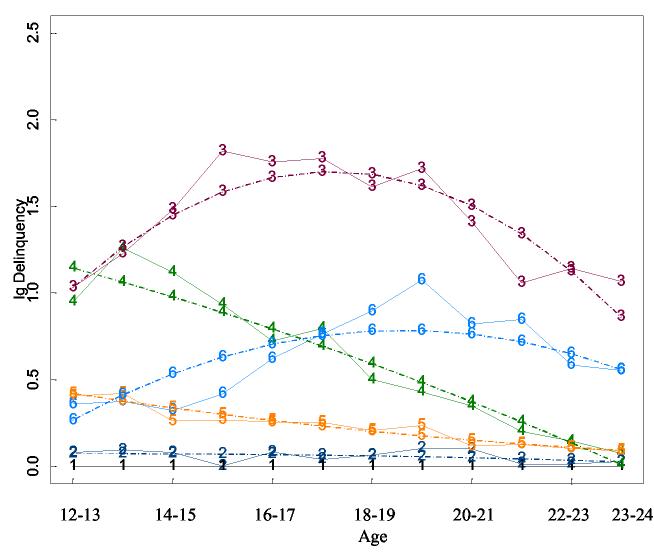

This study compared distinctive groups of male offenders that were already identified and described in an earlier report. Using LGMM (Muthén & Muthén, 2000; Muthén & Shedden, 1999), Wiesner and Capaldi (2003) identified homogeneous subgroups with distinctive developmental trajectories of self-reported offending behavior from ages 12-13 to 23-24 years for this sample (data from ages 24-25 to 25-26 years were not available when LGMM was performed). Analysis strategy, model selection criteria, and model fit statistics are described in detail in their report. Briefly, four model variants were tested reflecting a series of models with increasingly relaxed parameter constraints. Each model variant was tested in one-, two-, three-, four-, five-, and six-class models. Seven-class models were also tested, but failed to converge properly. Based on the Bayesian Information Criterion, LGMM indicated that a six-class model fit the data best. The posterior probability of it being the correct model was near one (.99), indicating that the model fit the data very well. The trajectory groups included 32 (15.7%) chronic high-level (HL) offenders, 38 (18.6%) chronic low-level (LL) offenders, 57 (27.9%) decreasing high-level (HL) offenders, 44 (21.6%) decreasing low-level (LL) offenders, 23 (11.3%) rare offenders, and 10 (4.9%) nonoffenders. The classification quality was reasonably good (see Nagin, 1999), as indicated by average posterior class probabilities of .92, .83, .85, .94, .99, and 1.00. The fitted and observed growth curves for the six offender trajectory groups are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Fitted (Dashed) versus Empirical (Solid) Growth Curves For Selected Latent Growth Mixture Model with Six Offender Trajectory Classes (n = 204). Note: Copyright © 2003 by Sage Publications. Reprinted with permission. Class 1 contains Nonoffenders (4.9%), Class 2 Rare Offenders (11.3%), Class 3 Chronic High-Level Offenders (15.7%), Class 4 Decreasing High-Level Offenders (27.9%), Class 5 Decreasing Low-Level Offenders (21.6%), and Class 6 Chronic Low-Level Offenders (18.6%).

Official arrests

Juvenile or adult court record searches were done locally for the study boys each year from ages 9-10 to 25-26 years (i.e., Waves 1 to 17). When families moved to other communities, the local authorities were contacted for permission to conduct record searches in their jurisdictions. The arrest records included the date and type of each offense. From these records, total scores were derived for three periods: Juvenile arrests (i.e., arrests before the age of 18 years), arrests from age 18 through 23-24 years (i.e., adult arrests until Wave 15), and arrests from age 24-25 through 25-26 years (i.e., additional adult arrests at Waves 16 and 17). Arrests for minor traffic violations or contempt of court were excluded from the total arrest counts.

Antisocial personality disorder

Lifetime diagnoses of DSM-IV antisocial personality disorder were derived from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS-IV; Washington University, 1998) that was administered at age 25-26 years. The DIS-IV was originally developed to assess the prevalence and incidence of specific psychiatric disorders in the general population. The fourth edition covers most of the DSM-IV disorders and can determine the developmental course of specific disorders over time. Participants answered the structured questions with regard to their previous life (i.e., estimation of lifetime prevalence rates).

Outcome measures

The three outcome measures, young adult alcohol use, drug use, and depressive symptoms, were obtained at ages 23-24 through 25-26 years (i.e., Waves 15-17). Answers were averaged across the three waves to gain more stable measures. All outcome and proxy measures were coded in the same direction, with higher scores indicating higher levels of problem behavior.

Alcohol use

The amount of alcohol consumption was assessed using a quantity-frequency index (QFI; see Dawson, 1998) measuring beer, wine, and hard liquor usage in the past year. The young men reported how many times they had consumed each beverage in the past year, and, if they did, how much they generally drank per drinking occasion (i.e., number of standard drinks, that is, cans/glasses/shots). The QFI, based on all three beverages, provided a measure of the average number of ounces of ethanol consumed per day across the past year. Prior to use in the analyses, the square-root transformation was applied to normalize the distribution of this indicator.

Drug use

The frequency of the young men's drug use in the past year was reported by the young men at each assessment time. Five items (i.e., consumption of marijuana, cocaine or crack, hallucinogens, opiates, other not-over-the-counter drugs) were rated on an eight-point scale from 0 (never) through 7 (once or more a day in the last year). The total score indicated the average annual frequency of marijuana and hard drug consumption.

Depressive symptoms

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) was used to assess depressive symptoms. The CES-D is a 20-item self-report scale that was designed to measure depressive symptomatology among adults in the general population, and it has been validated in several studies with adolescent samples (e.g., Garrison, Addy, Jackson, McKeown, & Waller, 1991). Respondents reported how they felt during the past week, with answers on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). The internal consistency for this scale was adequate (α = .90 for Wave 15, .93 for Wave 16, and .90 for Wave 17).

Proxy measures

For each outcome, we controlled for a proxy measure of the same behavior in childhood and in adolescence. Both proxy variables were averaged across multiple waves to gain more stable measures. For the childhood proxy measures, data from the Grades 4 and 6 (ages 9-10 and 11-12 years) assessments were aggregated (i.e., Waves 1 and 3). The childhood proxy measures were obtained before the assessment of the youths' delinquent behavior was initiated. For the adolescent proxy measures, data from Grades 8, 10, and 12 (ages 13-14, 15-16, and 17-18 years) were used (i.e., Waves 5, 7, and 9).3

For alcohol use, the proxies were based on self-reports, with the childhood proxy assessing the frequency of alcohol use in the past year and the adolescent proxy being measured as a quantity-frequency index similar to the young adult outcome variable. The childhood and adolescent proxies for drug use assessed the frequency of drug use (i.e., marijuana and hard drugs) in the last year, based on the study boys' self-reports. For depressive symptoms, the childhood proxy measure was the Child Depression Rating Scale from Birleson (1981) (18 items, internal consistency .71 and .76, respectively; three-point response scale from hardly ever to most of the time), and the adolescent proxy was the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale from Radloff (1977) (20 items, internal consistency .85, .86, and .86, respectively).

Control variables

The analyses were controlled for age of the young men, parents' socioeconomic status (SES: Hollingshead, 1975), antisocial propensity, and parents' arrests in Grade 4 (i.e., Wave 1). Antisocial propensity was measured with a composite variable of early antisocial behavior at age 9-10 years, derived from teacher (19 items, alpha .94) and parent (15 items, alpha .81 and .82) Childhood Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991) reports. Similar to earlier work with data from the OYS (e.g., Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999), the construct was created using items from the delinquent and aggressive behavior subscales, but excluding items from those scales that either overlapped with other constructs or were ambiguous (e.g., those pertaining to alcohol and drug use, and mood changes). The composite variable contained both overt and covert antisocial behaviors, including arguing a lot, being disobedient at school, getting into many fights, lying, and also cruelty, bullying, and meanness to others. The measure of parents' arrests was created from State of Oregon arrest records that were collected for all parents during the first assessment wave. It indicated the number of arrests ever experienced in state by both parents during their adult years (i.e., before participation in the OYS).

Results

Characterization and Validation of Trajectories of Offending

The offending pathways were further characterized and validated by comparing the six groups with regard to the number of official arrests and lifetime DSM-IV diagnoses of antisocial personality disorder. Key results are briefly summarized.

Official arrests

The arrest histories based on official records are presented in Table 1 for each trajectory group. As can be seen, tests for overall group differences were significant at each time period (i.e., juvenile arrests as well as the two adult arrest periods). Further, cumulative and average numbers of arrests decreased with increasing age in each trajectory group, as would be expected. Broadly speaking, the pattern of group differences was mostly consistent with our hypotheses. First, chronic HL offenders were characterized by the highest number of arrests, accounting for 2.75 times more than their share of the sample's total official arrests. Their ratio for self-reported offenses, which was computed for comparison purposes, was even higher (4.0; both ratios not shown). Further, all chronic HL offenders had at least one lifetime arrest, and 75% of them were arrested five times or more across the entire study period. However, the differences to the other groups with elevated offending behavior, especially the chronic LL and decreasing HL offenders, diminished over time and became nonsignificant by ages 24-26 years. Decreasing LL and rare and nonoffenders had the lowest numbers and shares of official arrests (ratios were 0.36, 0.36, and 0.08) and were indistinguishable from each other throughout the study period. Note that the nonoffenders' share of the total sample arrests was about five times less than that of the other two groups. Finally, decreasing HL and chronic LL offenders occupied the expected middle ranks between the two extremes (though several of the post-hoc group comparisons were not significant). Their ratios for official arrests were 0.99 and 0.91. Interestingly, the decrease in self-reported offenses over time was not paralleled by an analogous reduction in the number of official arrests for the decreasing HL offenders (e.g., their numbers of adult arrests were not below those of the chronic LL offenders). In conclusion, these findings demonstrated reasonably good face validity of the trajectories based on self-reported offending.

Table 1.

Official Arrests Derived from Court Records and DSM-IV Diagnosis of Antisocial Personality Disorder for Each Offender Trajectory Group

| Chronic HL Offenders (n = 32) | Chronic LL Offenders (n = 38) | Decreasing HL Offenders (n = 57) | Decreasing LL Offenders (n = 44) | Rare Offenders (n = 23) | Non-Offenders (n = 10) | Chi2 – Statistic (df = 5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Official Arrests | |||||||

| Juvenile Arrests (Before 18 Years of Age) | |||||||

| Total Number | 254 | 95 | 152 | 49 | 20 | 2 | NA |

| Average (SD) | 7.94 (7.87)C | 2.50 (4.84)A,B | 2.67 (4.09)B | 1.11 (2.69)A,B | .87 (1.32)A,B | .20 (.63)A | 10.951*** |

| Percent of Men With 1+ Arrests | 93.8% | 42.1% | 61.4% | 40.9% | 43.5% | 10.0% | 41.30*** |

| Percent of Men With 5+ Arrests | 62.5% | 21.1% | 19.3% | 6.8% | 4.3% | 0% | 42.61*** |

| Young Adulthood Arrests (Ages 18 to 23-24 Years) | |||||||

| Total Number | 74 | 36 | 60 | 10 | 12 | 1 | NA |

| Average (SD) | 2.31 (1.99)C | .95 (1.71)A,B | 1.05 (2.06)B,C | .23 (.60) A,B | .52 (1.31)A,B | .10 (.32)A | 7.161*** |

| Percent of Men With 1+ Arrests | 78.1% | 36.8% | 35.1% | 15.9% | 26.1% | 10.0% | 37.12*** |

| Percent of Men With 5+ Arrests | 18.8% | 5.3% | 7.0% | 0% | 4.3% | 0% | 12.99* |

| Arrests Ages 24-25 To 25-26 Years | |||||||

| Total Number | 9 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Average (SD) | .28 (.68) | .03 (.16) | .09 (.29) | .02 (.15) | .00 (0.0) | .00 (0.0) | 3.331** |

| Percent of Men With 1+ Arrests | 18.8% | 2.6% | 8.8% | 2.3% | 0% | 0% | 13.17* |

| Percent of Men With 5+ Arrests | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | NA |

| Total Official Arrests until Ages 25-26 Years | |||||||

| Percent of Men with 1+ Arrests Across Entire Study Period | 100.0% | 57.9% | 66.7% | 45.5% | 47.8% | 20.0% | 45.57*** |

| Percent of Men With 5+ Arrests Across Entire Study Period | 75.0% | 23.7% | 29.8% | 6.8% | 4.3% | 0% | 58.60*** |

| DSM-IV Antisocial Personality Disorder | |||||||

| Number of Men with Lifetime Diagnosis at Ages 25-26 Years (%) | 19 (59.4) | 5 (13.5) | 5 (8.9) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 61.74*** |

Note: The total number of official arrests until age 25-26 years can be computed for each offender trajectory group by adding up the numbers (i.e., arrests before age 18 yrs plus arrests ages 18 to 23-24 yrs plus arrests ages 24-25 to 25-26 yrs). Means with different subscripts differed significantly by Bonferroni post-hoc tests (Tamahane T2 post-hoc tests for variables with unequal variances) at p < .05. HL = High Level. LL = Low Level. NA = Not applicable.

Test-statistic was the overall F-statistic with df (5,198).

p < .001.

p < .01.

Lifetime DSM-IV diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder

As shown in Table 1, overall there were differences among the six self-report offending trajectory groups for diagnoses of antisocial personality disorder (APD). As expected, young men with lifetime diagnoses of APD were overrepresented in the chronic HL offender group. However, note that 40% of this group did not receive a diagnosis of APD. Rates of diagnoses were zero in the rare and nonoffender groups and negligible in the decreasing LL group. Only around one in ten of the men in the chronic LL and decreasing HL groups received a diagnosis of APD.

Descriptives for Young Adult Problem Behaviors and Corresponding Controls

Table 2 contains the means and standard deviations of the three young adult outcomes and their childhood and adolescent proxies for each offender trajectory group. Trajectory group means with different subscripts indicate a significant (p < .05) group difference (according to Bonferroni and Tamahane T2 post-hoc tests). Note that the rare and nonoffender groups were collapsed together into a very rare offender group, because both reported (almost) no offending behavior across the study period, contained relatively few individuals, and did not differ significantly in terms of the young adult outcomes and the corresponding control variables (on an alpha-level adjusted for number of comparisons). For space considerations, significant group differences are summarized only briefly. The groups did not differ significantly in terms of the childhood proxy measures. It is likely that marked group differences in these behaviors are not apparent until the adolescent years (i.e., when substantial numbers of youth initiate and actively engage in these behaviors). In contrast, group differences were significant for all adolescent proxies and the young adult outcomes. The overall pattern of group differences was fairly consistent and showed that chronic HL offenders usually had the highest scores (though pairwise group comparisons were not always significant). Decreasing HL and chronic LL offenders followed next, whereas decreasing LL offenders and especially very rare offenders had the lowest scores.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations of Control and Outcome Variables for Offender Trajectory Groups (SD in Parentheses)

| Chronic HL Offenders (n = 32) | Chronic LL Offenders (n = 38) | Decreasing HL Offenders (n = 57) | Decreasing LL Offenders (n = 44) | Very Rare Offenders (n = 33) | F – Statistic df(4, 199) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood Proxies | ||||||

| Alcohol Use | 0.09 (.93) | .04 (1.12) | .13 (1.11) | .01 (.95) | −.37 (.71) | 1.47 |

| Drug Use | .12 (1.15) | .02 (.85) | .19 (1.48) | −.19 (.36) | −.22 (.14) | 1.42 |

| Depressive Symptoms | .15 (1.22) | −.00 (.94) | .04 (.91) | .09 (.99) | −.33 (.98) | 1.16 |

| Adolescent Proxies | ||||||

| Alcohol Use | .97 (1.75)C | −.02 (.93) A,B,C | −.04 (.72) B | −.36 (.27) A | −.38 (.34) A | 12.54*** |

| Drug Use | 1.20 (1.56) C | −.22 (.51) A,B | .07 (.92) B | −.42 (.33) A | −.47 (.24) A | 22.61*** |

| Depressive Symptoms | .33 (1.00) B | −.13 (1.02) A,B | .14 (.99) A,B | −.00 (1.00) A,B | −.40 (.89) A | 2.73* |

| Young Adult Outcomes | ||||||

| Alcohol Use | .45 (1.29) C | .26 (1.09) B,C | .04 (1.03) A,B,C | −.31 (.76) A,B | −.38 (.42) A | 4.90*** |

| Drug Use | .87 (1.11) C | .10 (.95) B | −.13 (.96) A,B | −.21 (.90) A,B | −.46 (.59) A | 10.18*** |

| Depressive Symptoms | .61 (1.11) B | −.07 (.91) A | .01 (1.07) A,B | −.06 (.87) A | −.46 (.76) A | 5.20*** |

Note: For ease of comparison, all variables were standardized prior to analysis. Means with different subscripts differed significantly (p < .05) by Bonferroni post-hoc tests (Tamahane T2 post-hoc tests for variables with unequal variances). Very rare offenders = rare offenders plus nonoffenders together. HL = High Level. LL = Low Level.

p < .001.

p < .05.

Prediction of Young Adult Problem Behaviors

Hierarchical (or sequential) linear regression analyses (SPSS 11.0; see Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001) were conducted to test predictive effects of the offending trajectories on each young adult outcome, controlling for childhood and adolescent proxy measures of the outcome in question along with age, SES, parents' arrests, and antisocial propensity.4 Each outcome, namely, alcohol use, drug use, and depressive symptoms at ages 23-24 to 25-26 years, was predicted in three steps. In the first step, we entered age, SES, parents' arrests, antisocial propensity, and the childhood proxy measure of the predicted outcome. In the second step, we additionally entered four dummy variables, contrasting each offender trajectory group with a reference group (i.e., chronic HL and chronic LL offenders, respectively). Finally, in the third step, we added the adolescent proxy measure of the predicted outcome to examine whether this would eliminate the significance of distinct offender trajectories in predicting the young adult outcomes. It was expected that the adolescent proxy measures would be more powerful predictors of young adult outcomes compared to the childhood proxies, given their closer temporal proximity to young adulthood. Thus, the addition of the adolescent proxies permitted a more conservative test of the independent effects of differing offender trajectories on each young adult outcome. Table 3a shows the results for the models contrasting the chronic HL offenders with other trajectory groups, and Table 3b those for the models contrasting the chronic LL offenders with other trajectory groups.5

Table 3a.

Hierarchical Multiple Linear Regressions Predicting Young Adult Outcomes (Standardized Regression Coefficients)

| Alcohol Use |

Drug Use |

Depressive Symptoms |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Age | −.15* | −.13 | −.13 | −.04 | −.02 | −.02 | .05 | .06 | .06 |

| SES | .13 | .14 | .14 | .09 | .09 | .08 | .00 | .01 | .02 |

| Parents' Arrests | .04 | .04 | .04 | .00 | −.00 | .00 | −.12 | −.13 | −.13* |

| Antisocial Propensity | .15* | .07 | .06 | .16* | .03 | .02 | .18* | .09 | .05 |

| Childhood Control | .13 | .11 | .11 | −.09 | −.09 | −.13* | .08 | .06 | −.11 |

| Very Rare Offenders | --- | −.29** | −.29** | --- | −.50*** | −.33*** | --- | −.36*** | −.28*** |

| Decreasing LL Offenders | --- | −.31*** | −.31** | --- | −.46*** | −.27** | --- | −.23* | −.19* |

| Decreasing HL Offenders | --- | −.16 | −.16 | --- | −.44*** | −.30** | --- | −.25** | −.23** |

| Chronic LL Offenders | --- | −.09 | −.09 | --- | −.31*** | −.16 | --- | −.24** | −.18* |

| Adolescent Control | --- | --- | .01 | --- | --- | .29*** | --- | --- | .46*** |

| Incremental R2 | .07* | .07** | .00 | .03 | .16*** | .06*** | .06* | .07** | .17*** |

| R2 | .07* | .14*** | .14*** | .03 | .19*** | .24*** | .06* | .13*** | .30*** |

Note. Reference category was chronic HL offenders. The childhood proxy of the young adult outcome was assessed in Grades 4 and 6. The adolescent proxy of the young adult outcome was assessed in Grades 8, 10, and 12. Young adult outcomes were assessed at ages 23-24 through 25-26 years. HL = High Level. LL = Low Level.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 3b.

Hierarchical Multiple Linear Regressions Predicting Young Adult Outcomes (Standardized Regression Coefficients)

| Alcohol Use |

Drug Use |

Depressive Symptoms |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Age | −.15* | −.13 | −.13 | −.04 | −.02 | −.02 | .05 | .06 | .06 |

| SES | .13 | .14 | .14 | .09 | .09 | .08 | .00 | .01 | .02 |

| Parents' Arrests | .04 | .04 | .04 | .00 | −.00 | .00 | −.12 | −.13 | −.13* |

| Antisocial Propensity | .15* | .07 | .06 | .16* | .03 | .02 | .18* | .09 | .05 |

| Childhood Control | .13 | .11 | .11 | −.09 | −.09 | −.13* | .08 | .06 | −.11 |

| Very Rare Offenders | --- | −.20* | −.20* | --- | −.21* | −.19* | --- | −.13 | −.11 |

| Decreasing LL Offenders | --- | −.21* | −.21* | --- | −.13 | −.11 | --- | .02 | −.00 |

| Decreasing HL Offenders | --- | −.06 | −.06 | --- | −.08 | −.12 | --- | .03 | −.02 |

| Chronic HL Offenders | --- | .09 | .09 | --- | .29*** | .15 | --- | .22** | .17* |

| Adolescent Control | --- | --- | .01 | --- | --- | .29*** | --- | --- | .46*** |

| Incremental R2 | .07* | .07** | .00 | .03 | .16*** | .06*** | .06* | .07** | .17*** |

| R2 | .07* | .14*** | .14*** | .03 | .19*** | .24*** | .06* | .13*** | .30*** |

Note. Reference category was chronic LL offenders. The childhood proxy of the young adult outcome was assessed in Grades 4 and 6. The adolescent proxy of the young adult outcome was assessed in Grades 8, 10, and 12. Young adult outcomes were assessed at ages 23-24 through 25-26 years. HL = High Level. LL = Low Level.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

It can be seen in both tables that distinctive offender trajectories predicted all outcomes after controlling for age, SES, parents' arrests, antisocial propensity, and the childhood proxy of the given outcome. The increase in explained variance at the second step was significant in all cases. The addition of the adolescent proxy of the given outcome in the third step also significantly improved the amount of explained variance for drug use and depressive symptoms, but not for alcohol use. In most cases, the predictive effects of offender trajectories remained significant after controlling for the adolescent proxy, albeit they were somewhat reduced in strength.

Contrasting each group with chronic HL offenders

As shown in Table 3a, membership in both the very rare offending and the decreasing LL offending groups was consistently associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms and less frequent alcohol and drug consumption during early adulthood, relative to the chronic HL offender group. The effects remained significant after the adolescent proxy of each outcome was taken into account (see Step 3). This indicates that very rare offending and decreasing LL offending contributed independently to low levels of alcohol and drug use and depressive symptoms of the young men beyond the effects of adolescent levels of these behaviors. The predictive effects of decreasing HL offending paralleled those of very rare and decreasing LL offending, except that there was no significant predictive effect for young adult alcohol use. In other words, relative to chronic HL offending, decreasing HL offending was an independent contributor to lower levels of both drug (but not alcohol) use and depressive symptoms in early adulthood. In contrast to these three trajectory groups, chronic LL offending was less consistently related to the three outcomes. Interestingly, there was no effect for alcohol use, and the effect for drug use became nonsignificant after adolescent levels of drug use were taken into account. Hence, chronic LL offending was an independent contributor to just one of the three outcomes. Specifically, it was significantly linked to lower levels of young adult depressive symptoms compared to chronic HL offending.

Contrasting each group with chronic LL offenders

As can be seen in Table 3b, very rare offending was linked to lower levels of alcohol and drug consumption in early adulthood, relative to chronic LL offending, and these effects remained significant after each adolescent proxy was added to the regression equation. However, very rare offending was not an independent contributor to levels of young adult depressive symptoms. Compared to chronic LL offending, decreasing LL offending was associated with less alcohol consumption in young adulthood, even after controlling for adolescent levels of alcohol use. However, decreasing LL offending was not significantly linked with lower young adult drug use and depressive symptoms, compared with chronic LL offending. Finally, there were no significant predictive effects of decreasing HL offending (relative to chronic LL offending) on any of three young adult outcomes.

Discussion

Subgroups of offending trajectories spanning 12 years from early adolescence through young adulthood, based on annually assessed self-reported offending behavior gathered from an at-risk community sample of 204 young men, were identified in a previous study (Wiesner & Capaldi, 2003). The main goals of the current study were to investigate the external validity of these subgroups and to test the hypothesis that, congruent with propositions from developmental theories of crime, the trajectories would show predictive effects on three areas of adjustment in young adulthood, while controlling for antisocial propensity, parental arrests, demographic factors, and childhood and adolescent proxies of the outcomes. Tests of the external validity of the trajectories using official arrest records and diagnostic interviews generally indicated acceptable validity. Unique effects of the trajectories on the outcomes were found; in particular, persistent engagement in high levels of offending behavior was related to high levels of both depressive symptoms and drug use in early adulthood. These findings are consistent with the views that developmental failures associated with higher levels of antisocial behavior and crime are predictive of depressive symptoms in adulthood and that drug use may entrap young men in a criminal lifestyle.

Both juvenile and young adult arrest profiles showed significant convergence with the self-report based offending trajectories. As expected, the overall number of arrests was the highest in the chronic HL offender group, followed by decreasing HL offender, chronic LL offender, decreasing LL offender, and rare and nonoffender groups. In addition, it was found that lifetime diagnoses of APD were much more prevalent in the chronic HL offender group than in the other groups. These findings suggest that the external validity of the self-report offending trajectories is fairly good.

It is important to note that although the chronic HL offenders were much more likely to receive a diagnosis of APD, 40% of the group did not receive such a lifetime diagnosis. Considering their persistent elevated level of offending across the 12-year period and their high lifetime arrest rates (although the number of chronic HL offenders with severe arrest histories, as indexed by being arrested five or more times, was not as high, i.e., 75%), this may indicate that the DIS-IV is subject to a comparably high rate of false negatives for diagnosis of APD. It has been suggested that diagnostic interviews administered by lay administers (such as DIS) tend to underestimate prevalence rates (Eaton, Neufeld, Chen, & Cai, 2000; Murphy, Monson, Laird, Sobol, & Leighton, 2000). This could be either due to characteristics of the diagnostic system, to problems with retrospective recall over 10 or more years (in this case), or to qualitative differences in the assessed phenomena at hand. In any case, these findings provide a cautionary note and suggest that retrospective lifetime diagnoses of APD may not be the best means for identifying young men with a history of chronic (life-course persistent) high-level offending.

As predicted, findings indicated that very rare offenders (i.e., rare and nonoffenders collapsed together) and decreasing LL offenders fared better than did chronic HL offenders in all three areas of young adult adjustment; whereas decreasing HL offenders fared better in terms of drug use and depressive symptoms, and chronic LL offenders fared better only for depressive symptoms. By comparison, there were fewer differential outcomes when very rare offenders and the decreasing offender groups were contrasted with the chronic LL offenders. Very rare offenders fared better than did chronic LL offenders in two areas (alcohol and drug consumption), decreasing LL offenders in just one area (alcohol use), and decreasing HL offenders were virtually indistinguishable from chronic LL offenders in all three domains.

The higher level of drug use for the chronic HL offenders (further reflected by their heightened prevalence of illicit drug users: 56.3% of them reported using drugs once/twice or more per year in young adulthood), relative to other offender pathways, indicates that their young adult adjustment is particularly problematic, and it may be that illicit drug use contributes to their persistence in criminal behavior. Their higher level of depressive symptoms (further reflected by a heightened prevalence of men with serious depressive symptomatology: 37.5% had a total CES-D score of 16 or above at least once in young adulthood), compared with the other groups, was also of particular interest. Depressive symptoms were significantly predicted by chronic HL offending even after controlling for childhood and adolescent levels of depressive symptoms. This seems to indicate that such offending is associated with increases in depressive symptoms in young adulthood. These findings are consistent with the contention that problems and failures associated with antisocial behavior pose a risk for developing or worsening depressive symptoms in young adulthood. In prior work, Wiesner and Capaldi (2003) found that depressive symptoms and substance use in adolescence were significantly predictive of membership in the crime trajectory groups, controlling for other predictors. Therefore, developmentally there seems to be an intimate association between these factors, with reciprocal effects occurring over time. Although the processes that account for these associations are not yet well documented, the findings clearly suggest that the chronic HL offenders are in the greatest need for intervention and prevention efforts in order to avoid the societal costs of their serious adjustment problems in early adulthood.

The second group of chronic offenders, namely the chronic LL offenders, was not as clearly distinguishable from the two decreasing offender groups, as might have been expected on the basis of developmental theories of crime. Although they fared worse than the very rare offenders, thus partially confirming expectations, they did not fare significantly worse than decreasing LL offenders in two out of three young adult outcomes, and they did not differ at all from the decreasing HL offenders. At the same time, they also did not differ very systematically from the chronic HL offenders: Significant predictive effects of chronic LL offending were found for just depressive symptoms. This effect should be interpreted rather cautiously, given that it depended on the class assignment procedure that was utilized (see Footnote 5). The theoretical status of the chronic LL offenders consequently remains somewhat ambiguous. The lack of distinctiveness of this group seems to derive, in part, from the fact that the decreasing HL offenders did not make the overall relative improvements in adjustment in the three outcomes that might have been expected from their decreasing trajectory. However, the trajectory of the decreasing HL offenders remained the second highest through ages 17-18 years, and they had a high prevalence of juvenile and early adult arrests. Therefore, their quite active engagement in offending behavior may have had consequences that still considerably affected their adjustment by ages 23-26 years. Even though they decreased in offending, their criminal histories and likely associated problems, such as school failure, appear to have had longer-term consequences for this group. It will be important to examine more long-term adjustment profiles of each trajectory group (e.g., at ages 30+ years) before firm conclusions can be drawn about the degree to which decreasing HL and chronic LL offenders might be in heightened need for prevention and intervention efforts. Another interesting question is whether more systematic differences between the offending groups exist in other domains of life, including success in work careers and in the establishment of intimate relationships.

It appeared that the chronic HL offenders did not differ from other more active offender pathways (i.e., decreasing HL and chronic LL offenders) in terms of young adult alcohol use. This was somewhat surprising in light of the findings from other studies (e.g., Moffitt et al., 1996, 2002). Several explanations might account for this result. First, there could be cultural differences between alcohol use in young adulthood between New Zealand and the U.S. Second, the association between offending trajectories and alcohol use may possibly depend on the type or range of offending behaviors assessed in a given study. This argument is supported by the finding that violent offending trajectories, but not property offending trajectories, were predictive of young adult alcohol dependency in a study conducted by Hill et al. (2000). In a similar vein, the effects of offending pathways on young adult alcohol use may be a function of the outcome measure. Interestingly, the current study assessed the average daily amount of alcohol use, whereas other studies that found significant effects focused on more clinical indicators such as alcohol problems or DSM-IV alcohol dependence (e.g., Moffitt et al., 1996, 2002). Hence, it is possible that measures such as the one used in this study are not sensitive enough for detecting pervasive differences between the more active offending pathways. Still another explanation is offered by pseudomaturity theory (Newcomb, 1996). Accordingly, any behavior gains meaning in the context of the developmental period in which it occurs. Thus, linkages between offending pathways and specific outcomes may vary as a function of developmental periods. Specifically, consumption of alcohol may be maladaptive in early and middle adolescent years, but may not necessarily hold the same maladaptive value in young adulthood. In young adulthood, it is relatively normative to drink large amounts of alcohol.

These findings support the contention that different pathways of juvenile offending may bear differential risks for major aspects of young adult mental health, and thus support the view that developmental experiences, and not just antisocial propensity, are predictive of adult adjustment. Such effects would not have been detected readily by variable-centered approaches. The broad pattern of differences indicated that more adverse pathways of offending were linked to higher levels of subsequent young adult problems (see further qualifications to this statement as discussed below). In this sense, our findings were quite consistent with those of others. Farrington (1989) and Moffitt et al. (1996, 2002) reported a number of similar results for consumption of alcohol and drugs. Moffitt et al. (2002) also found differences for depression, but Hill et al. (2000) did not find significant differences for major depression. Such discrepancies might occur because effects may depend on the age of participants (e.g., age 21 years versus age 32 years), operationalization of outcomes (e.g., diagnoses of mental disorders versus continuous measures of problem behaviors), and informants (e.g., self-reports versus informant reports). More in-depth exploration of such issues is needed.

It should be emphasized that the demonstrated prospective effects of different trajectories of offending on the three young adult outcomes were controlled for important prior predictors, including childhood and adolescent proxies of the given outcome, parental criminality, and antisocial propensity. This was critical for disentangling spurious effects from plausible causal effects of different trajectories of offending on young adult problem behavior (i.e., for testing competing theoretical explanations of such effects) and provided a conservative test of our hypotheses. In the current study, the regression analyses showed a predictive effect of antisocial propensity on all three outcomes, which became nonsignificant when the offending trajectory variables were entered into the regression analyses, and significant increases were seen in the explained variance for all outcomes after the addition of the offending trajectory group variables. This leads us to conclude that, whereas some portion of the variance explained by trajectories of offending can be traced back to an underlying propensity factor, the other portion reflected plausible causal effects of variations in the course of offending over time on the three outcomes (as claimed by developmental theories of crime). This was particularly true for drug use.

These conclusions are dependent on the adequacy of the measure of an underlying propensity for antisocial behavior. The measurement of the propensity for crime has been a contentious issue in the literature. According to propensity theory (see Hirschi & Gottfredson, 1993), propensity for crime “is significantly comprised by early behavioral indicators of aggression and fighting” (Polakowski, 1994, p. 41) and is best measured in childhood. Our measure of antisocial propensity was assessed at ages 9-10 years and contained various indications of overt and covert antisocial behaviors, as observed by the boys' parents and teachers (not the boys themselves). Although this fits well with propensity theory, we note that data on additional features of the construct, such as childhood impulsivity, were not employed. However, confidence in the findings is strengthened by the additional controls, including that of parental criminality. Though correlational designs provide less definitive evidence of causality than do experimental manipulations, the findings point to a likelihood of causal effects.

It should be noted that some important issues remain to be addressed. First, the mechanisms through which juvenile offending trajectories are linked to adjustment levels in the young adult years should be examined. Possible mechanisms include limited environmental options such as academic failure and rejection by normative peers, as well as intentional or resulting affiliation with deviant peers and antisocial intimate partners who reinforce deviant behaviors. Second, the outcome measures used in this study did not involve clinical diagnoses, and it remains to be seen if findings would be similar in such a case. Third, the study was conducted with data from a mostly Caucasian sample of at-risk young men, and the effects of sample diversity need to be studied more closely.

Identification of the offending trajectory groups was based on right-censored data – which is necessarily the case when studying ongoing behaviors. Some young men who were assigned into one of the decreasing offender groups may restart criminal activities in later years (i.e., after ages 23-24 years). Inspection of official arrest profiles from ages 24-25 through 25-26 years (as well as of self-report profiles for the same period; findings were not reported) indeed indicated some engagement in offending for the two decreasing groups, although levels were relatively low and activities were confined to small subsets of young men within each group. Hence, the possibility that right-censoring introduced some (limited) bias to the findings cannot be ruled out. Future data collection with this sample will permit assessment of such effects.

Other factors possibly affecting the findings include the fact that the sample size was relatively small. However, Sampson, Laub, and Eggleston (2004) examined the effect of sample size on number of trajectory groups identified for criminal behavior, and they found that the number of groups identified stabilized at a sample size of about 200. It is possible that the use of self-reports for both trajectories and outcomes inflated the estimation of the relationships between trajectories of offending behavior and young adult problem behavior. Consequently, replicating the findings of this study with data collected from other informants is important.

In sum, the findings of the study supported the hypothesis that young men's histories of criminal involvement through adolescence and young adulthood are predictive of their levels of depressive symptoms and drug use in early adulthood. The developmental courses of offending behavior for these young men had significant consequences in adulthood, even with substantial controls for prior levels of the behaviors and for possible alternative predictors. Engagement in higher levels of offending, and particularly persistence in such behavior, was associated with higher levels of drug use and depressive symptoms in adolescence and adulthood. As 16% of the boys recruited from all 4Th-grade boys in at-risk schools belonged to the HL chronic delinquency group, this is clearly a problem of considerable magnitude. These serious problems may help to entrap these men in an antisocial life-style, at least for longer than is developmentally normative, and indicate that intervention should be targeted on these problems for highly delinquent adolescents.

Footnotes

Support for the Oregon Youth Study was provided by Grant No. R37 MH 37940 from the Prevention, Early Intervention, and Epidemiology Branch, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), U. S. Public Health Service (PHS). Support for the Couples Study was provided by Grant HD 46364 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), U.S. PHS. Support was also provided by Grant MH 46690 from the Prevention, Early Intervention, and Epidemiology Branch, NIMH, Office of Research on Minority Health, U. S. PHS. We thank Jane Wilson, Rhody Hinks, and the Oregon Youth Study team for high quality data collection, and Lee Owen for assistance with data preparation.

Seven items, mostly school-related, had to be excluded because they were not given after Wave 11. Public disorder offenses (5 items) and liquor law violations (1 item) were also excluded. As recommended by the scale author (see reprint in Flanagan & Maguire, 1990), two more items were excluded because of item overlap. This resulted in 30 items selected for the present analyses (20 nonindex and 10 index offenses). None of the remaining items included status offenses or traffic violations.

Occasionally, participants reported annual frequencies for a given offense that were far beyond the numbers reported by others. Because this occurred very rarely and usually applied to just one or two study boys, we decided to trim down those outlying values (values > 365 were collapsed into the value 365, which was the maximum value reported most often in this study). Comparisons of the average scores based on the original values relative to those based on the trimmed down values for each offender trajectory class indicated that this procedure did not bias the results in a clearly discernible way (for example, even though there were a few differences in terms of absolute values, there were no marked changes in the shapes of offending behavior).

Data from so-called minor waves were not used, because only a limited number of variables were assessed during minor waves (e.g., Waves 2, 4, and 6).

There were some missing values for 5 of the 14 study variables (less than 1% in all cases). Although the rate of missing values was quite small, listwise deletion would have resulted in loss of statistical power and somewhat biased parameter estimates (Graham & Hofer, 2000; Little & Rubin, 1987; Schafer & Olsen, 1998). Missing values therefore were estimated in this study with the EM-algorithm (see Graham & Hofer, 2000) using the software package NORM (Schafer, 1999). Even when the missing at random (MAR) assumption is not fully met, it can be assumed that this procedure produces less biased parameter estimates than listwise deletion or mean substitution methods (Graham & Hofer, 2000; Schafer & Olsen, 1998). Because the EM-algorithm is known to produce somewhat unreliable standard errors, the regression analyses were repeated using multiple imputation (i.e., three datasets imputed in NORM). However, the key results were the same. Hence, we reported the results based on the EM-algorithm.

Because individual assignment probabilities were high for most young men and borderline cases with similar or equal membership probabilities across groups were extremely rare, we employed the conventional approach of assigning each participant to the group that best conforms to his observed behavior over time, based on the maximum posterior probability of group membership. However, it may be argued that assignment uncertainty for even only a few borderline cases is influential in relatively small samples such as the OYS. Therefore, we repeated all regression analyses using a randomized class assignment procedure that accounts for class membership uncertainty (Bandeen-Roche, Huang, Munoz, & Rubin, 1999; Bandeen-Roche, Miglioretti, Zeger, & Rathouz, 1999): Randomized class assignment was performed three times, and a regression analysis was performed for each assignment solution. Results were then combined across the three solutions (using NORM; Schafer, 1999). Overall, the results of the regression analyses were very similar for both methods of class assignment (with the exception of the effects of chronic LL offending on depressive symptoms in Table 3a and those of decreasing LL offending on alcohol use in Table 3b, which were not significant for the randomized class assignment solution).

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist and 1991 profile. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson T, Mahoney JL, Wennberg P, Kuehlhorn E, Magnusson D. The cooccurrence of alcohol problems and criminality in the transition from adolescence to young adulthood: A prospective longitudinal study on young men. Studies on Crime and Crime Prevention. 1999;8:169–188. [Google Scholar]

- Bandeen-Roche K, Huang G-H, Munoz B, Rubin GS. Determination of risk factor associations with questionnaire outcomes: A methods case study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;150:1165–1178. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandeen-Roche K, Miglioretti DL, Zeger SL, Rathouz PJ. Latent variable regression for multiple discrete outcomes. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1997;92:1375–1386. [Google Scholar]

- Birleson P. The validity of depressive disorder in childhood and the development of a self-rating scale: A research report. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1981;22:73–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1981.tb00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block JH, Gjerde PF. Depressive symptoms in late adolescence: A longitudinal perspective on personality antecedents. In: Rolf J, Masten AS, Cicchetti D, Neuchterlein KH, Weintraub S, editors. Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1990. pp. 334–360. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: I. Familial factors and general adjustment at Grade 6. Development and Psychopathology. 1991;3:277–300. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: II. A 2-year follow-up at Grade 8. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:125–144. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Chamberlain P, Fetrow RA, Wilson J. Conducting ecologically valid prevention research: Recruiting and retaining a “whole village” in multimethod, multiagent studies. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1997;25:471–492. doi: 10.1023/a:1024607605690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Patterson GR. An approach to the problem of recruitment and retention rates for longitudinal research. Behavioral Assessment. 1987;9:169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Stoolmiller M. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: III. Prediction to young-adult adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:59–84. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Stoolmiller M, Clark S, Owen LD. Heterosexual risk behaviors in at-risk young men from early adolescence to young adulthood: Prevalence, prediction, and STD contraction. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:394–406. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung I-J, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Gilchrist LD, Nagin DS. Childhood predictors of offense trajectories. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2002;39:60–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. An historical perspective on the discipline of developmental psychopathology. In: Rolf J, Masten AS, Cicchetti D, Neuchterlein KH, Weintraub S, editors. Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1990. pp. 2–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Schneider-Rosen K. An organizational approach to childhood depression. In: Rutter M, Izard CE, Read PB, editors. Depression in young people: Developmental and clinical perspectives. Guilford; New York: 1986. pp. 71–134. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, Campbell SB. Developmental psychopathology and family process. Theory, research, and clinical implications. The Guilford Press; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA. Volume of ethanol consumption: Effects of different approaches to measurement. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:191–197. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Capaldi DM, Yoerger K. Middle childhood antecedents to progression in male adolescent substance use: An ecological analysis of risk and protection. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1999;14:175–206. [Google Scholar]

- D'Unger AV, Land KC, McCall PL, Nagin DS. How many latent classes of delinquent/criminal careers? Results from mixed poisson regression analyses. American Journal of Sociology. 1998;103:1593–1630. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Neufeld K, Chen L-S, Cai G. A comparison of self-report and clinical diagnostic interviews for depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:217–222. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH., Jr. The life course and human development. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development. 5th ed. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1998. pp. 939–991. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Ageton SS, Huizinga D, Knowles BA, Canter RJ. The prevalence and incidence of delinquent behavior: 1976 – 1980. Behavioral Research Institute; Boulder, CO: 1983. (National Youth Survey Report No. 26). [Google Scholar]

- Evans TD, Cullen FT, Burton VS, Dunaway RG, Benson ML. The social consequences of self-control: Testing the general theory of crime. Criminology. 1997;35:475–504. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP. Later adult life outcomes of offenders and nonoffenders. In: Brambring M, Loesel F, Skowronek H, editors. Children at risk: Assessment, longitudinal research, and intervention. Walter deGryter; Berlin: 1989. pp. 220–244. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, van Kammen WB, Schmidt L. Self-reported delinquency and a combined delinquency seriousness scale based on boys, mothers, and teachers: Concurrent and predictive validity for African-Americans and Caucasians. Criminology. 1996;34:501–525. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Nagin DS. Offending trajectories in a New Zealand birth cohort. Criminology. 2000;38:525–551. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan TJ, Maguire K, editors. Sourcebook of criminal justice statistics 1989. USGPO; Washington, DC: 1990. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison CZ, Addy C, Jackson KL, McKeown R, Waller JL. The CES-D as a screen for depression and other psychiatric disorders in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:636–641. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199107000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T. A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Hofer SM. Multiple imputation in multivariate research. In: Little TD, Schnabel KU, Baumert J, editors. Modeling longitudinal and multilevel data. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. pp. 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Muthén BO. Adolescent and young adult antisocial and adult alcohol use disorders: A fourteen-year prospective follow-up in a National Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:524–528. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KG, Chung I-J, Herrenkohl TI, Hawkins JD. Consequences of trajectories of violent and property offending; Paper presented at the 52nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Criminology; San Francisco, CA. Nov, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T, Gottfredson MR. Commentary: Testing the general theory of crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1993;30:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four-factor index of social status. Department of Sociology, Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1975. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Hops H, Lewinsohn P, Andrews JA, Roberts RE. Psychosocial correlates of depressive symptomatology among high school students. Journal of Clinical and Child Psychology. 1990;19:211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Elliott DS. Reassessing the reliability and validity of self-report delinquency measures. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 1986;2:293–327. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Capaldi DM. The association of antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms between partners and risk for aggression in romantic relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:82–96. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritsen JL. The age-crime debate: Assessing the limits of longitudinal self-report data. Social Forces. 1998;77:127–155. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]