Abstract

Deltex (DTX) and AIP4 are the human orthologues of the Drosophila deltex and Suppressor of deltex, which have been genetically described as being antagonistically involved in the Notch signalling pathway. Both genes encode E3 ubiquitin ligases of the RING (Really interesting new gene)-H2 and HECT (Homologous to E6AP carboxyl terminus) families, respectively. In an attempt to understand the molecular basis of their genetic interactions, we studied the relationship between DTX and AIP4 in the absence of activation of the Notch pathway. We show here that both molecules interact and partially colocalize to endocytic vesicles, and that AIP4 targets DTX for lysosomal degradation. Furthermore, AIP4-generated polyubiquitin chains are mainly conjugated through lysine 29 of ubiquitin in vivo, indicating a link between this type of chain and lysosomal degradation.

Keywords: SU(DX)–AIP4–Itch, Deltex, Notch, ubiquitination

Introduction

Notch signalling is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism allowing the correct specification of multiple cell types. Genetic analysis in Drosophila supports the idea that Deltex (DTX, the product of the Dx gene) is a positive regulator of Notch signalling (Diederich et al, 1994), acting upstream of an active intracytoplasmic form of Notch and downstream of full-length Notch in the signal-receiving cell. The Drosophila DTX protein contains: amino-terminal WWE domains (characterized by two conserved Trp residues and a Glu residue), which are important for its direct interaction with Notch (Matsuno et al, 1995; Zweifel et al, 2005); a proline-rich domain; and a carboxy-terminal, highly conserved, RING (Really interesting new gene)-H2 finger domain, which is also found in a number of other proteins that act as ubiquitin ligases (Jackson et al, 2000). DTX function seems to be conserved in mammals and so far three members of the family have been identified (Matsuno et al, 1998; Ordentlich et al, 1998; Kishi et al, 2001). Despite a rather abundant literature, the biochemical function of the DTX protein in the Notch pathway has remained elusive and controversial (Takeyama et al, 2003; Hori et al, 2004).

Suppressor of deltex (SU(DX)) is a negative regulator of the Notch pathway (Mazaleyrat et al, 2003), acting antagonistically to the positive regulator DX in Drosophila. Its human orthologue is AIP4 (atrophin-1-interacting protein 4), and its orthologue in the mouse is Itch (Fostier et al, 1998; Perry et al, 1998; Cornell et al, 1999). This HECT-type E3 ubiquitin ligase has been proposed to promote ubiquitination of Notch (Qiu et al, 2000) and also of other substrates (see Discussion). In Drosophila, SU(DX) regulates the post-endocytic sorting of Notch in the early endosome to an Hrs (HGF-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate)- and ubiquitin-enriched subdomain before transport to the late endosome (Sakata et al, 2004; Wilkin et al, 2004). As a first approach at deciphering the complex relationship that exists among DTX, AIP4 and Notch in mammals, we decided to focus on AIP4 and DTX. Given their role in regulating the steady-state level of various substrates, we asked whether AIP4 and DTX could interact and regulate each other's activity or level. We show here that, in agreement with their known epistatic interactions, AIP4 and DTX interact directly and that AIP4 ubiquitinates DTX and targets it for lysosomal degradation. Furthermore, this regulation involves the endocytic pathway and ubiquitination by unconventional ubiquitin chains.

Results

AIP4 interacts with DTX

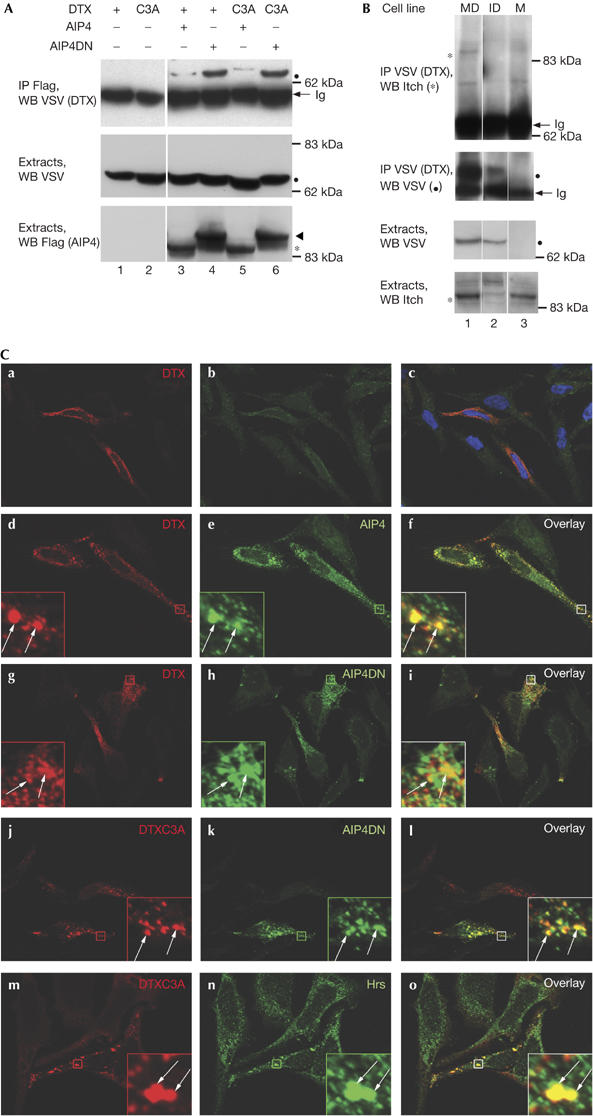

To characterize the relationship between AIP4 and DTX, we co-transfected HEK293T cells with either wild-type proteins (DTX1 and AIP4) or proteins in which the E3 activities have been abolished by point mutations (named DTXC3A and AIP4DN, respectively). By immunoprecipitating AIP4 proteins with Flag antibody, we could detect wild-type or C3A DTX (Fig 1A, upper panel, lanes 3–6), showing that these proteins interact and that their ubiquitin-ligase activity is not required for the interaction. The amount of co-immunoprecipitating DTX or DTXC3A was much higher with AIP4DN than with AIP4 (compare lanes 4,6 with 3,5), when compared with similar quantities of these proteins in the extracts (middle and bottom panels). The same phenomenon was previously observed in the case of the degradation of LMP2A (latent membrane protein 2A; an Epstein–Barr virus protein implicated in the maintenance of viral latency) by AIP4 (Winberg et al, 2000), indicating that AIP4 E3 ubiquitin-ligase activity could be involved in DTX degradation. To confirm the DTX1–AIP4 interaction under more physiological conditions, and as no DTX1 antibody is available, we established by retroviral infection pools of mouse embryonic fibroblasts, derived from either wild-type or Itch−/− embryos, and stably expressing a vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-tagged version of DTX1. These cells are hereafter named M and I for the parental wild-type and Itch−/− lines, and MD and ID, respectively, for the DTX-transduced wild-type and Itch−/− lines. Endogenous Itch could specifically be co-immunoprecipitated with VSV–DTX from the MD cells (Fig 1B). We next examined the distribution of DTX and AIP4 by using immunofluorescence microscopy of transfected HeLa cells (endogenous AIP4 cannot be detected by immunofluorescence with the available antibodies). As AIP4 has been shown to be strongly associated with endocytic vesicles (Marchese et al, 2003; Angers et al, 2004; Fang & Kerppola, 2004), we treated the transfected HeLa cells with saponin before fixation to permeabilize the cholesterol-containing membranes and eliminate most cytosolic proteins. With this procedure, signals for transfected DTX or DTXC3A were associated with intracellular vesicles (Fig 1C a,d,g,j,m), a subset of which was also positive for AIP4 (d–f), AIP4DN (g–l) or endogenous Hrs (m–o). The association of stably expressed DTX with endocytic vesicles was confirmed in MD and ID cells (see Fig 2C).

Figure 1.

Deltex and AIP4 interact and are associated with endocytic vesicles. (A) Analysis of Deltex (DTX)–AIP4 interaction. HEK293T cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-tagged DTX or DTXC3A, Flag-tagged AIP4 or AIP4DN, as indicated. Extracts or AIP4 immunoprecipitates (IP Flag) were analysed by immunoblotting with antibodies against VSV and Flag, as indicated on the left. Filled circles, arrowheads and asterisks indicate the position of DTX, AIP4DN and AIP4, respectively, in all the figures; white lines indicate that intervening lanes have been spliced out. (B) Interaction between stably transfected DTX and endogenous AIP4. VSV (DTX) immunoprecipitates or extracts from MD, ID or M cells were analysed by immunoblotting with antibodies against VSV or Itch. The ID pool of cells expresses an overall lower level of DTX than MD cells, owing to the variability in retroviral infection efficiency. (C) Colocalization of DTX or DTXC3A with AIP4 or AIP4DN. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with DTX (a–i), DTXC3A (j–o) together with AIP4 (d–f) or AIP4DN (g–l) expression vectors. Cells were permeabilized with saponin before fixation. DTX, AIP4 and endogenous Hrs were detected using antibodies against VSV, Flag or Hrs, respectively, and shown by CY3- (a–l), CY5- (m–o) or Alexa 488-coupled secondary antibodies. Right panels are merges of the two adjacent panels; Hoechst staining is also shown in (c). Insets represent enlarged views (eightfold) of the boxed regions. The arrows indicate colocalizations. ID, DTX-transduced Itch−/− lines; Ig, immunoglobulin heavy chain; M, parental wild-type lines; MD, DTX-transduced wild-type lines; WB, western blot.

Figure 2abc.

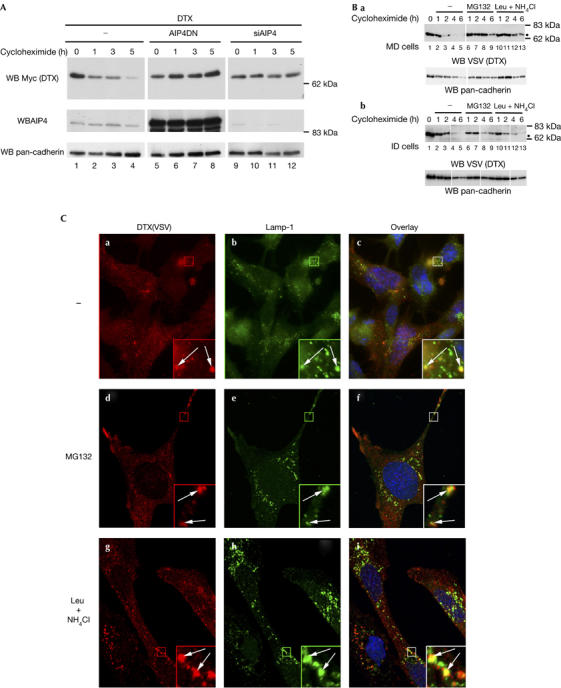

AIP4 targets Deltex for lysosomal degradation. (A) Effect of inactivating or downregulating AIP4 on the half-life of Deltex (DTX). HEK293T cells were transfected with DTX–Myc expression vector alone or together with either AIP4DN or the AIP4 short interfering RNA (siAIP4) vector. Cells were treated with cycloheximide 24 h after transfection and collected at different time points. Equal amounts of total protein cell lysates were subjected to western blot analysis using antibodies against Myc, AIP4 and pan-cadherin as loading controls. (B) Half-life measurement of DTX in MD (a) and ID (b) cells. Cycloheximide treatment was applied alone or together with MG132 (10 μM) or leupeptin and NH4Cl (Leu+NH4CI; 50 μM and 10 mM, respectively), then the experiment was carried out as in (A). DTX was detected with vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) antibody.

AIP4 induces DTX degradation

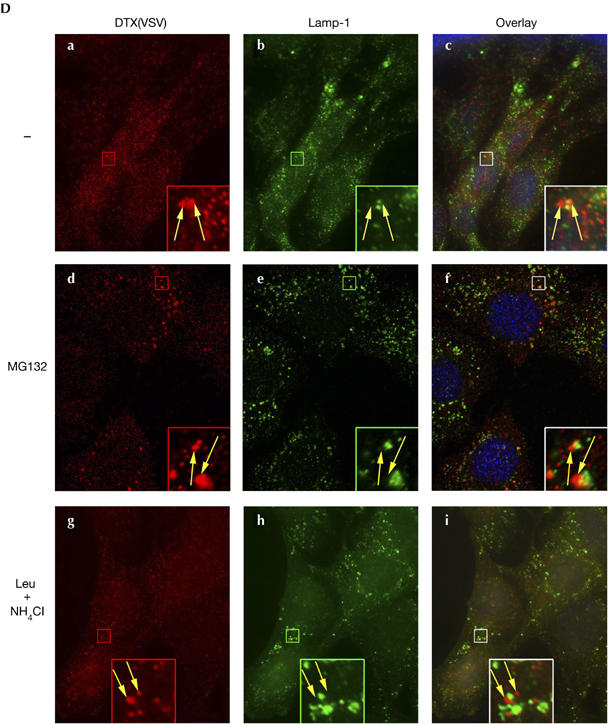

To further investigate the putative role of AIP4 in DTX regulation, we reduced the level of AIP4 by short interfering RNA silencing (see supplementary Fig S1 online) and monitored the half-life of DTX by using a cycloheximide experiment. Overexpressed DTX protein showed a half-life of about 2 h (Fig 2A, lanes 1–4), which was extended to more than 5 h when expressing AIP4DN (lanes 5–8) or silencing endogenous AIP4 (lanes 9–12). Overexpressing a dominant-negative form of another E3 ubiquitin ligase, cbl, did not affect DTX turnover (data not shown). We also monitored DTX degradation in MD and ID cells in the presence of lysosomal (leupeptin+NH4Cl) or proteasomal (MG132) inhibitors. DTX showed a half-life of 2 h (Fig 2B, lanes 1–5) and was stabilized by treatment with MG132 (lanes 6–9) in both cell lines. By contrast, DTX degradation was delayed in leupeptin and NH4Cl-treated MD cells (lanes 10–13) and not affected in ID cells. Thus, DTX is subject to a double regulation by proteasomal and lysosomal degradation, the latter resulting from AIP4 activity. To further confirm these data, we compared the localizations of DTX and LAMP-1, a marker of the late endosome/lysosome compartment. In MD cells, DTX signals overlapped partially LAMP-1-positive vesicles (Fig 2Ca–c). This colocalization was enhanced when cells were treated with leupeptin and NH4Cl (g–i). By contrast, in ID cells, DTX seemed to be predominantly adjacent to LAMP-1 vesicles, rather than coincident as in MD cells, irrespective of leupeptin and NH4Cl treatment (Fig 2D). In both cell lines, MG132 treatment increased the intensity of DTX staining without affecting its localization (Fig 2Dd–f), confirming that the proteasome partially accounts for DTX degradation. These data indicate that in the absence of AIP4, DTX remains associated with early endosomes, whereas in the presence of AIP4, at least some DTX molecules follow the endocytic pathway until their degradation in the lysosomes.

Figure 2d.

(C,D) Localization of DTX in MD (C) or ID (D) cells. Cells were treated with MG132 (d–f) or leupeptin and NH4Cl (g–i) for 2 h, then fixed and permeabilized. DTX and LAMP-1 were detected using CY3–VSV and monoclonal 1D4B with an Alexa 488-coupled secondary antibody. The right panels are merges of the two adjacent panels, showing nuclei staining with Hoechst. Insets represent enlarged views (fivefold) of the boxed regions. DTX colocalizes with LAMP-1 in MD cells (white arrows in C) and is adjacent to LAMP-1 puncta in ID cells (yellow arrows in (D)). ID, DTX-transduced Itch−/− lines; MD, DTX-transduced wild-type lines; WB, western blot.

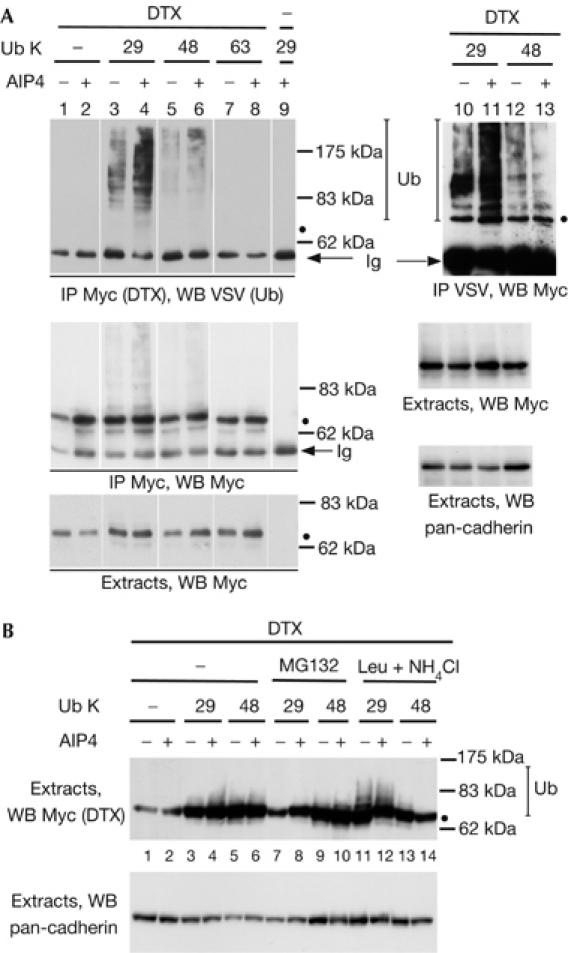

AIP4 catalyses the formation of K29-polyubiquitin chains

To identify the type of isopeptide linkage catalysed by AIP4, we generated expression vectors encoding VSV-tagged ubiquitins mutated in all but one of the critical lysine residues used to polymerize ubiquitin molecules (such as K29, K48 or K63), thus allowing the formation of a single type of polyubiquitin chain. We immunoprecipitated DTX in extracts derived from cells co-transfected with these ubiquitin vectors and displayed the ubiquitinated products by immunoblotting with anti-VSV (Fig 3A). Ubiquitination of DTX was predominantly detected when using ubiquitin (Ub) K29 (upper panel, lanes 3,4), as compared with Ub K48 or K63 (lanes 5–8). It was further enhanced when AIP4 was co-transfected, whereas the K48 or K63 ubiquitinations were less affected. The absence of signal when using extracts devoid of DTX in the presence of Ub K29 (lane 9), as well as the apparent molecular weight of the VSV-positive molecules (starting at the position of DTX, indicated by a black dot), suggested that these ubiquitinated products were derived from DTX and not from a nonspecific or DTX-associated protein. We also carried out the reverse experiment, in which the ubiquitinated molecules were first immunoprecipitated and the DTX forms detected by western blotting (lanes 10–13). A DTX-containing ladder was enriched in the presence of AIP4 and Ub K29 (lane 11), confirming that the K29-polyubiquitinated species were mainly derived from DTX. Using other ubiquitin expression vectors in which only one lysine was mutated to an arginine, thus preventing one type of chain to be polymerized, also showed the preferential ubiquitination of DTX through K29 chains (supplementary Fig S2 online). The same type of experiment was carried out using AIP4 as a ubiquitin acceptor, showing that under overexpression conditions, AIP4 targets its own degradation after autoubiquitination through K29-linked chains (supplementary Fig S3 online). These results indicate that formation of K29-linked polyubiquitin chains could constitute a characteristic of AIP4 activity.

Figure 3.

AIP4 polyubiquitinates itself, as well as Deltex, by K29-linked chains. (A) Ubiquitination of Deltex (DTX). HEK293T cells were transfected with Myc-tagged DTX, AIP4 and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-tagged ubiquitin (Ub) expression vectors. The number indicates the only lysine residue remaining in the ubiquitin molecule. DTX immunoprecipitates (IP Myc, lanes 1–9) or ubiquitin immunoprecipitates (IP VSV, lanes 10–13) and the corresponding extracts were analysed by successive immunoblotting with antibodies against VSV, Myc and pan-cadherin. (B) Stabilization of ubiquitinated DTX by lysosomal inhibitors. 293T cells were treated with MG132 or leupeptin and NH4Cl (Leu+NH4Cl) for 2 and 48 h after transfection. Extracts were analysed as described above. WB, western blot.

To establish a link between the type of chains formed and the fate of the ubiquitinated molecules, we treated the transfected cells with either MG132 or leupeptin and NH4Cl, and immunoblotted the extracts for DTX (Fig 3B). A ladder of ubiquitinated forms of DTX was specifically stabilized in the presence of both Ub K29 and lysosomal enzymes inhibitors (lanes 11,12), suggesting a connection between K29-linked polyubiquitin chains and lysosomal degradation.

Discussion

DTX localizes to the endocytic pathway

Two research groups have previously proposed that significant fractions of endogenous or exogenous DTX proteins were localized to the nucleus (Yamamoto et al, 2001; Hu et al, 2003). However, in our study and also in others (Ordentlich et al, 1998; Hori et al, 2004), transiently transfected or stably expressed DTX1 was never detected in the nucleus. AIP4 was shown to be closely associated with endocytic vesicles (Marchese et al, 2003; Angers et al, 2004; Fang & Kerppola, 2004). Our results show that DTX is associated with similar vesicles, even in cells devoid of AIP4. Thus, although the interaction with AIP4 could help to reach the late endocytic compartment, it might not be the only determinant of DTX localization. We did not detect any direct interaction between DTX and Hrs (data not shown), although they partially colocalize. Recent data in Drosophila indicate an interaction in endocytic vesicles between DTX and Krz, the non-visual β-arrestin homologue (Mukherjee et al, 2005). As this molecule contains AP2 and clathrin interaction domains, and has been shown to be associated with seven-transmembrane-spanning receptors, it might account for DTX localization. DTX does not contain any of the canonical PPXY motifs that Martin-Serrano et al (2005) suggest mediate interaction with AIP4. It has been recently shown that distinct WW domains (containing two conserved Trp residues separated by 20–22 amino acids) in the same protein can have distinct binding specificities, and that a given WW domain can recognize several motifs with variable affinities (Ingham et al, 2005). In particular, the WW domains of the Nedd4 family members preferentially recognize not only PPXY motifs but also PPLP or PR motifs. The latter exist in the proline-rich domain of DTX and could account for DTX interaction with AIP4.

AIP4 targets DTX degradation

Our results show that AIP4 is involved in the degradation of DTX, in the absence of activation of the Notch receptor. We observe degradation of DTX through both the proteasomal and lysosomal pathways, with AIP4 accounting for the lysosomal targeting. However, the half-life of DTX is not markedly shorter in wild-type than Itch−/− cells, although its transportation is affected in the latter, suggesting that a partial compensatory effect might exist in Itch−/− cells. In Drosophila, SU(DX) negatively regulates Notch signalling in different developmental contexts and has been proposed to act upstream of the regulation of Notch target genes (Mazaleyrat et al, 2003). DX has an opposite effect on Notch signalling and a reduction of SU(DX) E3 activity results in suppression of loss-of-function phenotypes of DX. Thus, their genetic interactions could be due to one molecule regulating the other. In Drosophila, Sakata et al (2004) have observed that the amount of DTX increased in the absence of Nedd4 or when a dominant-negative form of this E3 ligase was overexpressed. These data are in perfect accordance with our conclusions. By contrast, Wilkin et al (2004) have proposed that SU(DX) regulates the post-endocytic sorting of Notch in the early endosome to an Hrs- and ubiquitin-enriched subdomain. Wilkin et al rule out models by which SU(DX) downregulates Notch by modulating DTX, because dx-null mutants are suppressed by SU(DX) mutation and fail to prevent the induction of ectopic Notch signalling by SU(DX)ΔHECT. To resolve these apparent discrepancies, we propose that AIP4 could have a bifunctional role by inducing the degradation of both DTX and Notch in the absence of activation, as has been suggested for Nedd4 in Drosophila (Sakata et al, 2004).

K29 polyubiquitination—a signature of AIP4?

The isopeptide linkage of a polyubiquitin chain is a particularly important determinant of its cellular function; for example, K48-linked chains commonly target proteins for proteasomal degradation (Aguilar & Wendland, 2003). Our results show that AIP4 directs polymerization of ubiquitin, primarily through an unconventional linkage involving residue K29, both on itself and on an heterologous substrate, DTX. To our knowledge, this is one of the first examples of K29-linked chains described in vivo (see also Johnson et al, 1995). Among the HECT-E3 ubiquitin ligase family, KIAA10 has been described as catalysing the formation of K48- and K29-linked chains in vitro, whereas E6AP produced only K48-linked chains (Wang & Pickart, 2005). Bai et al (2004) have proposed that Itch promotes Smad2 polyubiquitination by the classical K48 linkage. Nevertheless, they compared only Ub K48 with Ub K63; so it is possible that Ub K29 would have been incorporated more efficiently in the polyubiquitin chains. Conversely, CXCR4 and Hrs have been proposed to be monoubiquitinated by AIP4 (Marchese & Benovic, 2001; Marchese et al, 2003). As AIP4 might be important in the lysosomal targeting of its substrates, such as CXCR4 (Marchese et al, 2003), Jun (Fang & Kerppola, 2004), endophilin A1 (Angers et al, 2004) or DTX (our study), it remains to be explained whether the topology of the chains assembled by AIP4 on its various substrates would define their fate.

Methods

Immunofluorescence. Cells were grown on glass coverslips and were transiently transfected using Fugene transfection reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) for 24 h. HeLa cells were permeabilized with PBS, containing 0.02 % saponin for 5 min, then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts were first fixed, then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton. Cell preparations were mounted in Mowiol (Calbiochem, Merck Biosciences, Darmstadt, Germany) and images acquired with 0.3 μm sections using a Axioplan 2 imaging with ApoTome system (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging Inc., Le Pecq, France).

Cell extracts, immunoprecipitations and immunoblots. 293T cells were collected 24 h after transfection, washed in PBS buffer and lysed in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 1% NP-40, 400 mM NaCl supplemented with 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 5 mM N-ethylmaleimide (Sigma, Lyon, France). Immunoprecipitations and immunoblots were carried out as described previously (Gupta-Rossi et al, 2004).

Measurement of DTX half-life. Cycloheximide (50 μg/ml; Sigma) and other drugs were applied to subconfluent MD, ID cells or 293T cells 24 h after transfection. Protein levels were determined after collecting and lysing cells at the indicated time points and analysing by immunoblotting.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Stenmark, S. Artavanis-Tsakonas, P. Charneau, M. Rossi and A. Atfi for generous gifts of materials. This project was supported in part by a grant from Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (#3485) to C.B., and by grants from the Ministry of Research (#032547) and from the European Community (#018683, NoE RUBICON) to A.I.

References

- Aguilar RC, Wendland B (2003) Ubiquitin: not just for proteasomes anymore. Curr Opin Cell Biol 15: 184–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angers A, Ramjaun AR, McPherson PS (2004) The HECT domain ligase Itch ubiquitinates endophilin and localizes to the trans-Golgi network and endosomal system. J Biol Chem 279: 11471–11479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Yang C, Hu K, Elly C, Liu Y-C (2004) Itch E3 ligase-mediated regulation of TGF-βsignaling by modulating Smad2 phosphorylation. Mol Cell 15: 825–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell M, Evans DAP, Mann R, Fostier M, Flasza M, Monthatong M, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Baron M (1999) The Drosophila melanogaster Suppressor of deltex gene, a regulator of the Notch receptor signaling pathway, is an E3 class ubiquitin ligase. Genetics 152: 567–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederich RJ, Matsuno K, Hing H, Artavanis-Tsakonas S (1994) Cytosolic interaction between deltex and Notch ankyrin repeats implicates deltex in the Notch signaling pathway. Development 120: 473–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang D, Kerppola TK (2004) Ubiquitin-mediated fluorescence complementation reveals that Jun ubiquitinated by Itch/AIP4 is localized to lysosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 14782–14787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fostier M, Evans DAP, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Baron M (1998) Genetic characterization of the Drosophila melanogaster Suppressor of deltex gene: a regulator of Notch signaling. Genetics 150: 1477–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta-Rossi N, Six E, LeBail O, Logeat F, Chastagner P, Olry A, Israel A, Brou C (2004) Monoubiquitination and endocytosis direct γ-secretase cleavage of activated Notch receptor. J Cell Biol 166: 73–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori K, Fostier M, Ito M, Fuwa TJ, Go MJ, Okano H, Baron M, Matsuno K (2004) Drosophila Deltex mediates Suppressor of Hairless-independent and late-endosomal activation of Notch signaling. Development 131: 5527–5537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu QD et al. (2003) F3/contactin acts as a functional ligand for Notch during oligodendrocyte maturation. Cell 115: 163–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham RJ et al. (2005) WW domains provide a platform for the assembly of multiprotein networks. Mol Cell Biol 25: 7092–7106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson PK, Eldridge AG, Freed E, Furstenthal L, Hsu JY, Kaiser BK, Reimann JDR (2000) The lore of the RINGs: substrate recognition and catalysis by ubiquitin ligases. Trends Cell Biol 10: 429–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ES, Ma PCM, Ota IM, Varshavsky A (1995) A proteolytic pathway that recognizes ubiquitin as a degradation signal. J Biol Chem 270: 17442–17456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi N et al. (2001) Murine homologs of deltex define a novel gene family involved in vertebrate Notch signaling and neurogenesis. Int J Dev Neurosci 19: 21–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchese A, Benovic JL (2001) Agonist-promoted ubiquitination of the G protein-coupled receptor CXCR4 mediates lysosomal sorting. J Biol Chem 276: 45509–45512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchese A, Raiborg C, Santini F, Keen JH, Stenmark H, Benovic JL (2003) The E3 ubiquitin ligase AIP4 mediates ubiquitination and orting of the G protein-coupled receptor CXCR4. Dev Cell 5: 709–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Serrano J, Eastman SW, Chung W, Bieniasz PD (2005) HECT ubiquitin ligases link viral and cellular PPXY motifs to the vacuolar protein-sorting pathway. J Cell Biol 168: 89–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuno K, Diederich RJ, Go MJ, Blaumuller CM, Artavanis-Tsakonas S (1995) Deltex acts as a positive regulator of Notch signaling through interactions with the Notch ankyrin repeats. Development 121: 2633–2644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuno K, Eastman D, Mitsiades T, Quinn AM, Carcanciu ML, Ordentlich P, Kadesch T, Artavanis-Tsakonas S (1998) Human deltex is a conserved regulator of Notch signalling. Nat Genet 19: 74–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazaleyrat SL, Fostier M, Wilkin MB, Aslam H, Evans DAP, Cornell M, Baron M (2003) Down-regulation of notch target gene expression by suppressor of deltex. Dev Biol 255: 363–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A, Veraksa A, Bauer A, Rosse C, Camonis J, Artavanis-Tsakonas S (2005) Regulation of Notch signalling by non-visual β-arrestin. Nat Cell Biol 7: 1191–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordentlich P, Lin A, Shen CP, Blaumueller C, Matsuno K, Artavanis Tsakonas S, Kadesch T (1998) Notch inhibition of E47 supports the existence of a novel signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol 18: 2230–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry WL, Hustad CM, Swing DA, O'Sullivan TN, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG (1998) The itchy locus encodes a novel ubiquitin protein ligase that is disrupted in a18H mice. Nat Genet 18: 143–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu L, Joazeiro C, Fang N, Wang HY, Elly C, Altman Y, Fang DY, Hunter T, Liu YC (2000) Recognition and ubiquitination of Notch by Itch, a Hect-type E3 ubiquitin ligase. J Biol Chem 275: 35734–35737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata T, Sakaguchi H, Tsuda L, Higashitani A, Aigaki T, Matsuno K, Hayashi S (2004) Drosophila Nedd4 regulates endocytosis of Notch and suppresses its ligand-independent activation. Curr Biol 14: 2228–2236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeyama K, Aguiar RCT, Gu L, He C, Freeman GJ, Kutok JL, Aster JC, Shipp MA (2003) The BAL-binding protein BBAP and related Deltex family members exhibit ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase activity. J Biol Chem 278: 21930–21937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Pickart CM (2005) Different HECT domain ubiquitin ligases employ distinct mechanisms of polyubiquitin chain synthesis. EMBO J 24: 4324–4333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin MB et al. (2004) Regulation of Notch endosomal sorting and signaling by Drosophila Nedd4 family proteins. Curr Biol 14: 2237–2244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winberg G, Matskova L, Chen F, Plant P, Rotin D, Gish G, Ingham R, Ernberg I, Pawson T (2000) Latent membrane protein 2A of Epstein–Barr virus binds WW domain E3 protein-ubiquitin ligases that ubiquitinate B-cell tyrosine kinases. Mol Cell Biol 20: 8526–8535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto N et al. (2001) Role of Deltex-1 as a transcriptional regulator downstream of the Notch receptor. J Biol Chem 276: 45031–45040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweifel ME, Leahy DJ, Barrick D (2005) Structure and Notch receptor binding of the Tandem WWE domain of Deltex. Structure 13: 1599–1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

supplementary Information