Introduction, Case History, and Diagnosis

Neuropathic osteoarthropathy, otherwise known as Charcot neuroarthropathy, is a chronic, degenerative arthropathy and is associated with decreased sensory innervation. Numerous causes of this arthropathy have been described. Herein, we report a case of neuropathic osteoarthropathy of the shoulder, also known as Charcot shoulder, secondary to syringomyelia. The pathophysiology, clinical findings, and diagnostic work-up options are discussed.

Case History

The patient is a 36-year-old, wheelchair-dependent man who presented with left shoulder pain and weakness. He had normal use of both upper extremities until 3 months prior, at which time he began having left shoulder dull pain. The patient also has been noticing progressive weakness and difficulty with range of motion in his left shoulder. This has impaired his ability to use his wheelchair. The patient denies any fevers, chills, weight loss, anorexia, or other constitutional symptoms. Past medical history is significant for multiple injuries from a motorcycle accident nearly 20 years previously, and having multiple operations on his lower extremities. He has no history of spinal surgery. He does not take medications nor does he smoke.

On physical examination, the patient is a healthy-appearing male in a wheelchair. He has full range of motion of his cervical spine. He has full range of motion, 5/5 strength, and intact sensation of his right upper extremity. Examination of the patient's left upper extremity reveals normal skin and no abnormal masses. There is no supraclavicular lymphadenopathy. Active abduction is limited to 80°. He has 4/5 biceps strength, 5/5 triceps strength, and 5/5 motor strength distally in the left upper extremity. He has a 2+ radial pulse, and his median, ulnar, and radial nerves are all intact at the level of the hand. With passive range of motion, there is motion through the humerus distal to where the shoulder joint would be expected.

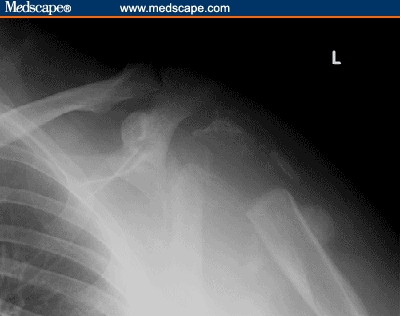

Radiographic evaluation shows complete destruction of the left humeral head with fragmentation (Figure 1). The scapula appears intact.

Figure 1.

Anterior-posterior radiograph of left shoulder. There is complete destruction of the left humeral head with fragmentation. The distal clavicle and scapula appear intact.

Diagnosis

Neuropathic osteoarthropathy of the shoulder.

Clinical Commentary

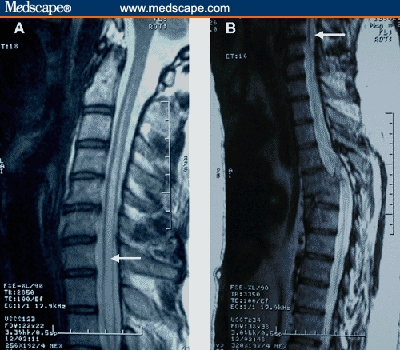

With a history of spinal injury and having not undergone a surgical stabilization, a syrinx was suspected. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study of the patient's cervical and thoracic spine was obtained which revealed a syrinx (Figure 2). The syrinx was decompressed by a neurosurgeon, and the patient is considering his shoulder reconstructive options.

Figure 2.

MRI of cervical and thoracic spine. (A) Sagittal T2 image of cervical and upper thoracic spine showing syrinx (arrow) in spinal cord. (B) Sagittal T2 images of lower cervical and thoracic spine, revealing distal extent of syrinx (arrow) and prior vertebral fracture.

Neuropathic osteoarthropathy, also known as Charcot neuroarthropathy, is a chronic, degenerative arthropathy and is associated with decreased sensory innervation. Mitchell, in 1831, initially identified a destructive arthropathy associated with diseases involving peripheral nerves. Subsequently in 1868, Charcot described neuropathic arthropathy in a patient with tabes dorsalis. Although Charcot initially described the sequelae of tertiary syphilis, his name is given to neuropathic arthropathy regardless of its etiology.

There are numerous causes of neuropathic osteoarthropathy, the 3 most common being diabetes, syphilis, and syringomyelia. Diabetic patients tend to have involvement of the joints of the foot and ankle, whereas larger joints such as the knee are commonly affected in patients with syphilis.[1] Patients with syringomyelia tend toward involvement of the shoulder and elbow.[2–7]

There are 2 theories describing the pathogenesis of neuropathic osteoarthropathy. These are the neurotraumatic and neurovascular theories. The neurotraumatic theory, first described by Johnson[8] in 1967, involves repetitive trauma sustained by an insensate joint. The neurovascular theory, proposed by Allman and colleagues,[9] describes active bone resorption by osteoclasts secondary to sympathetic dysfunction and a neurally mediated persistent hyperemia. If fractures and other forms of trauma are involved, this theory suggests that they occur secondarily.

Syringomyelia is a disorder involving a fluid-containing cavity (syrinx) within the spinal cord. These cavities commonly occur in the lower cervical and upper thoracic segments, and the distension may propagate proximally. Causes of syringomyelia include congenital, traumatic, infectious, degenerative, vascular, or tumor-related.[10–13] MRI is the most effective imaging modality for visualization of a syrinx.

The pathophysiology of syringomyelia involves the disruption of the adjacent gray and white matter. The initial fibers damaged are the pain and temperature sensory fibers as they cross the midline. Their loss in the upper extremity, with intact position sense and motor function, is often the first clinical sign. It is the loss of these sensory fibers that is thought to result in the etiology of neuropathic arthropathy of the shoulder. As the syrinx grows or propagates, the dorsal column fibers or anterior horn cells may be affected. Areflexia, muscle weakness, and atrophy results, commonly involving the hand intrinsics. Additionally, disruption of the sympathetic pathways may result in a Horner's syndrome or vasomotor and trophic changes, again most common in the hand.

Summary

Syringomyelia is a potential cause of neuropathic osteoarthropathy of the shoulder, or “Charcot shoulder.” The work-up of a patient with shoulder dysfunction should include a thorough history and physical and radiographic plain films. Once a neuropathic joint has been diagnosed, its etiology should be pursued with aseptic joint aspiration to look for infection or tumor, and an MRI to evaluate for syringomyelia if the etiology remains in doubt.

In this case, a syrinx resulted from cord compression from a previous trauma. The patient did not have a decompression and stabilization surgery in the past. The syrinx propagated proximally over time, resulting in Charcot shoulder and presentation to our orthopaedic oncology clinic with weakness and an unusual-appearing radiograph.

Contributor Information

Aaron B. Cullen, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of California, Davis Medical Center, Sacramento, California.

Onder Ofluoglu, Orthopaedics Department, Kartal Education and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

Rakesh Donthineni, Orthopaedic Oncology; Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of California, Davis Medical Center, Sacramento, California.

References

- 1.Shapiro G, Bostrom M. Heterotopic ossification and Charcot neuroarthropathy. In: Chapman MW, editor. Chapman's Orthopaedic Surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 3245–3262. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones J, Wolf S. Neuropathic shoulder arthropathy (Charcot joint) associated with syringomyelia. Neurology. 1998;50:825–827. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.3.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Browne RF, Murphy SM, Torreggiani WC, Munk PL. Musculoskeletal case 29. Neuropathic shoulder secondary to syringomyelia. Can J Surg. 2003;46:300, 309–310. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolawole T, Banna M, Hawass N, Khan F, Rahman N. Neuropathic arthropathy as a complication of post-traumatic syringomyelia. Br J Radiol. 1987;60:702–704. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-60-715-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drvaric DM, Rooks MD, Bishop A, Jacobs LH. Neuropathic arthropathy of the shoulder. A case report. Orthopedics. 1988;11:301–304. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19880201-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riente L, Frigelli S, Delle SA. Neuropathic shoulder arthropathy associated with syringomyelia and Arnold-Chiari malformation (type I) J Rheumatol. 2002;29:638–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nozawa S, Miyamoto K, Nishimoto H, Sakaguchi Y, Hosoe H, Shimizu K. Charcot joint in the elbow associated with syringomyelia. Orthopedics. 2003;26:731–732. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20030701-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson JT. Neuropathic fractures and joint injuries. Pathogenesis and rationale of prevention and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1967;49:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allman RM, Brower AC, Kotlyarov EB. Neuropathic bone and joint disease. Radiol Clin North Am. 1988;26:1373–1381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodbelt AR, Stoodley MA. Post-traumatic syringomyelia: a review. J Clin Neurosci. 2003;10:401–408. doi: 10.1016/s0967-5868(02)00326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klekamp J. The pathophysiology of syringomyelia – historical overview and current concept. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002;144:649–664. doi: 10.1007/s00701-002-0944-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biyani A, el Masry WS. Post-traumatic syringomyelia: a review of the literature. Paraplegia. 1994;32:723–731. doi: 10.1038/sc.1994.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams B. Syringomyelia. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1990;1:653–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]