Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

Constipation is a highly prevalent and bothersome disorder that negatively affects patients' social and professional lives and imposes a heavy economic burden on patients and society. Most patients with chronic constipation are evaluated and treated in the primary care setting. Primary care clinicians often underestimate how much they can accomplish in the evaluation of a patient with constipation before they make a referral. There are numerous steps that primary care clinicians can take to address these issues and maximize the benefits of the referral process, including understanding key elements of an effective diagnostic work-up, familiarizing themselves with the utility of various diagnostic tests of colonic and anorectal function, implementing strategies/instruments to optimally communicate what they are striving to achieve through the referral process (eg, via a referral form), and developing a network of long-term working relationships with local gastroenterologists.

Introduction

Constipation is a highly prevalent disorder that affects approximately 12% to 19% of North Americans – estimates vary widely depending on study design and methodology.[1–6] For many persons, constipation is a chronic problem, lasting from several months to several years.[2] The multiple symptoms of chronic constipation encompass much more than reduced stool frequency; many patients report straining, feelings of incomplete evacuation, abdominal pain/discomfort, bloating, hard and/or small stools, or a need for digital manipulation to enable defecation.[5,7–12] For research purposes (eg, enrolling patients into clinical trials), the Rome II diagnostic criteria for constipation are generally used (Table 1).[2,13]

Chronic constipation leads to decreased quality of life. The general well-being of patients with this disorder is lower than that of comparable normal populations,[14,15] and symptom severity has a negative correlation with perceived quality of life (ie, the more severe the symptoms, the lower the quality of life).[14]

The economic impact of constipation is substantial both for patients and society as a whole. Between 1979 and 1981, constipation resulted in 13.7 million days per year of restricted activity; in 1975, 3.43 million days per year of bed disability[16] occurred; and annually in the United States, over-the-counter (OTC) laxative sales total more than $800 million.[1] Although they account for only approximately one third of those with chronic constipation, adults with chronic constipation who seek medical care consume significant and costly healthcare resources. For instance, total healthcare costs for patients with constipation enrolled in the California Medicaid program (n = 105,130) for a 15-month period amounted to $18,891,007.[17]

Most patients with chronic constipation are evaluated and treated in the primary care setting. In 2000, constipation was 13th on the list of leading physician diagnoses for gastrointestinal (GI) disorders in outpatient clinic visits in the United States. Furthermore, constipation was ranked as the sixth leading GI symptom that prompts outpatient visits.[16] One study estimated ambulatory healthcare use related to constipation in the United States by assessing data from the 2001 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and the 2001 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Study findings showed that more than 5.7 million visits related to constipation were made in the outpatient setting in 2001. Of these, constipation was the primary reason for a visit or was the primary diagnosis in 44%, 51%, and 56% of visits to physician offices, hospital outpatient clinics, and emergency rooms, respectively.[18]

Primary care clinicians are often frustrated when faced with patients who do not respond to empiric treatment measures. When, how, and to whom to refer such patients is often unclear, and expectations of the referral process – to gain a better understanding of the underlying cause of the constipation and guidance on management strategies – are often not met (see Sidebar). Furthermore, primary care physicians often underestimate how much they can accomplish in the evaluation of a patient with constipation before they make a referral.

This article discusses common communication barriers between primary care clinicians and gastroenterologists in the care of patients with chronic constipation, and suggests strategies and tools that can be used to facilitate effective communication and optimize patient care. Suggestions for conducting a thorough prereferral work-up for patients with constipation are also presented, and the usefulness of various diagnostic tests that are commonly employed is discussed.[19]

Considerations Regarding the Referral Process

Referral for a Consultation vs Referral for a Procedure

Numerous factors may prompt a primary care clinician to refer a patient with constipation to a gastroenterologist for a diagnostic test or for further evaluation, including failure of the patient to respond to empiric treatment, descriptions of worsening symptoms despite continuing treatment, and/or development of warning signs (“red flags”) suggestive of organic disease (eg, presence of anemia, unintended weight loss, family history of colon cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, onset of symptoms before age 50).[20] Miscommunication regarding the needs of the referring physician and his or her expectations of the gastroenterologist may result in frustration, annoyance, and disappointment for the referring physician.

Terminology related to the referral process tends to be used inconsistently in the literature. For the purposes of this review, the phrases “referral for a procedure” vs “referral for a consultation” will be used. Generally, if a procedure is requested, the gastroenterologist allots only the amount of time needed to perform that procedure; no extra time is scheduled for taking an in-depth patient history or conducting a thorough and complete physical examination. In essence, no services beyond the technical aspect of the procedure are rendered. A procedure-specific billing code is used for this type of patient visit, and no consultation is included. In contrast, when a consultation is requested, the primary care clinician temporarily places the patient in the hands of the gastroenterologist. In this situation, the specialist schedules adequate time to take an in-depth patient history, conducts a thorough physical examination, prepares a list of possible causes of the patient's symptoms, recommends diagnostic tests to be performed (or conducts the tests and explains their rationale and the clinical relevance of the findings), and suggests a treatment approach and follow-up plan for the patient. A consultation-specific billing code is used for this type of patient visit.

Referral Form

The key to effective communication between a primary care clinician and a gastroenterologist at the time of initial referral is a clear explanation of what is being requested and what is expected. This communication will improve patient care by maximizing the likelihood of meaningful feedback.[19,21,22]

When a patient is referred to a gastroenterologist, the reason for referral must be stated as well as whether any procedures are requested to diagnose and treat the patient's problem. In addition, the referring physician should also include the suspected underlying cause of constipation, relevant findings of a recent physical and/or rectal examination, laboratory and diagnostic tests conducted to date and their results, and lifestyle measures and/or medications tried (including doses, duration, effectiveness, and adverse effects). These measures will help the specialist to understand clearly the needs of the patient, will ensure that the primary care clinician's expectations are met, and will prevent unnecessary duplication of diagnostic tests.[21]

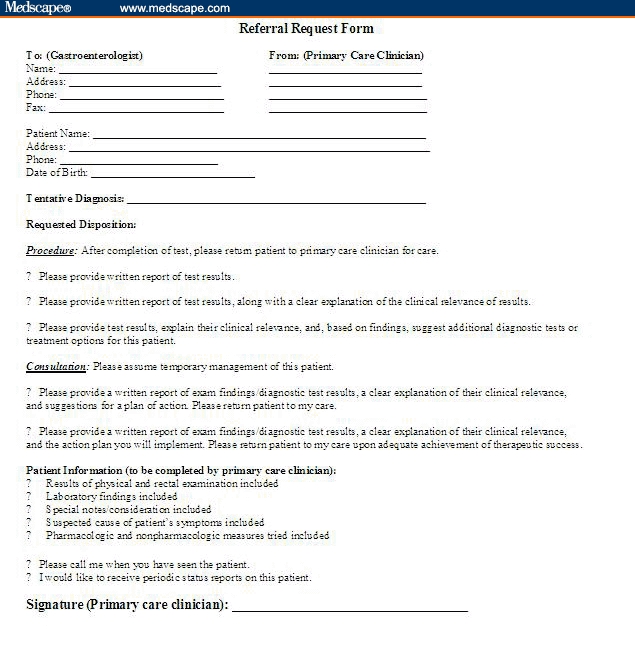

Use of a standardized referral form (such as the one depicted in Figure 1) can facilitate the compilation of important information and encourage 2-way communication. A basic referral form can be customized to meet the needs of the individual primary care clinician.[21] Some organizations have disease-specific referral forms on which an appropriate work-up before referral is outlined.[19]

Figure 1.

Sample referral form.

Establishing a Network of Gastroenterologic Specialists

Careful selection of a gastroenterologist for patient referral is a challenging but critical task that will increase both the likelihood of a successful working relationship and meaningful feedback. The first step is to determine which local physicians are specifically interested in consultative medicine, which are primarily interested in performing procedures, and which have an interest or specialty in a particular area, such as disorders related to the esophagus (eg, acid reflux disease, dysphagia, functional heartburn, odynophagia, rumination syndrome), small intestine (eg, duodenal ulcers, intestinal obstruction, bacterial overgrowth), large intestine (eg, fecal incontinence, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease) or liver. Strategic working relationships can then be developed with these practitioners. Although establishing this cadre of GI specialists may initially be labor-intensive, it is well worth the effort. Once such collaborative relationships are formed, they are usually ongoing.[21]

Suggested Approach to Evaluating Patients With Constipation in the Primary Care Setting

Primary care clinicians may underestimate the thoroughness with which they can conduct a prereferral work-up for a patient with constipation.[19] The following sections describe a stepwise approach that clinicians can follow in the primary care setting.

The Patient History

A detailed patient history is the first and most important step of the diagnostic evaluation. Asking the right questions helps the clinician to identify the extent to which constipation is affecting the patient's life and helps in distinguishing whether the patient's symptoms are the result of a secondary vs a primary cause (Table 2).[1,2,7,10,20,23–31] A great deal can be learned about the patient's experience of and attitudes toward constipation by asking questions such as those listed in Table 3. One need not be hesitant to ask patients about their use of physical maneuvers and positioning (eg, digital manipulation, squatting) to relieve symptoms.[1] Patients are often relieved to find that they are not alone in resorting to these measures.

Table 2.

Primary (Idiopathic) and Secondary Constipation

| Primary (Idiopathic) Constipation |

|---|

|

| Secondary Constipation[7,10,20,23,26,27,30,31] |

|

| Other conditions (eg, depression or anxiety, degenerative joint disease) |

Table 3.

|

The Physical Examination

The physical examination is directed toward identifying the underlying cause(s) of constipation. A neurologic examination excludes the possibility of systemic illness.[1,32] An assessment of the patient's nutritional status and changes in weight may indicate unintentional loss or gain.[7] Examination of the skin that reveals pallor and reduced body hair, skin dryness, and fixed edema is suggestive of hypothyroidism.[7]

Examination of the abdomen begins with a search for evidence of previous surgery that may have affected nerves critical to colonic and pelvic floor function, such as the pudendal nerves.[33] In addition, examining the abdomen for masses, distension, tenderness, the presence of stool throughout the colon, and high-pitched or absent bowel sounds is essential.[1,7]

The Rectal Examination

Optimally, a careful rectal examination should be performed in every patient with constipation.[2] While the patient is comfortably placed in the left lateral recumbent position, visual inspection of the perianal area may reveal the presence of fissures, hemorrhoids, masses, skin tags, or evidence of previous surgery.[1,2] Anal fissures or hemorrhoids may be found in patients who complain of painful defecation. Excoriation of the perianal skin (eg, red, flaky skin) is often indicative of fecal soiling, which is especially likely to occur in patients with fecal impaction and overflow incontinence.[1] Stroking of the perianal skin should elicit a reflex contraction of the external anal sphincter.[1] Absence of this contraction may indicate the presence of a neurologic defect, such as nerve injury secondary to previous surgery, spinal stenosis, or spinal cord tumor.

A thorough rectal examination also includes digital assessment for strictures, masses, a rectocele, and hemorrhoids.[1,2,7] Stool may be examined for color and consistency at this time.[7] The presence of hard stool in the rectal vault may indicate an obstruction or fecal impaction.[23]

Asking the patient to voluntarily contract his or her external anal sphincter helps in assessing its strength. The internal anal sphincter can be palpated and its tone assessed. The patient should bear down as if having a bowel movement.[1] The external and internal anal sphincters should relax during this maneuver. Elevated tone or incomplete relaxation of the anal sphincters is an indication of pelvic floor dysfunction. Additionally, during straining, the perineum should descend 1–3.5 cm; reduced descent may indicate an inability to relax the pelvic floor muscles.[2] Alternatively, excessive descent (> 3.5 cm) is indicative of a lax perineum, which can result in incomplete evacuation. Rectal prolapse can be identified during straining if a fold of tissue strikes the examining finger, or if the tissue is pushed out through the anus. Formation of a rectocele may be noted during attempted defecation. If the patient reports the need to apply pressure on the perineum or the posterior wall of the vagina for evacuation, a rectocele should be suspected.

The Symptom Diary

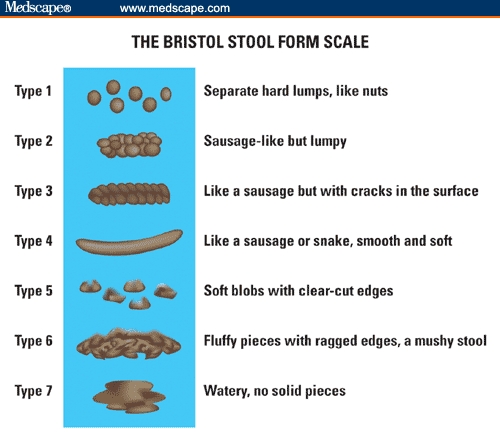

Primary care clinicians can ask patients to keep a diary in which they record their symptoms and describe their bowel habits for 2 or more weeks.[23,26] Patients should record details related to their bowel movements, such as frequency, quality (eg, painful, difficult), result (feelings of complete/incomplete evacuation), and time spent in the bathroom. They should also record the daily amount of dietary fiber they consume, as well as fiber supplements, OTC medications, and alternative remedies taken. Because patients are oftentimes embarrassed to discuss their stool patterns in detail, the Bristol Stool Scale (Figure 2), with its visuals and descriptive words, may be a clinically valuable tool that can be used in the primary care setting. The presence of hard or lumpy stools is usually indicative of slow intestinal transit time.[34,35]

Figure 2.

An essential element of the diary review process is careful assessment of the results. Patients often indicate that they use dietary fiber or fiber supplements, but upon further questioning, they may reveal that inadequate amounts were consumed, insufficient doses of medication were taken, or an inadequate treatment duration was attempted (eg, < 1 or 2 weeks). An open dialogue with the patient to discuss diary entries will help the clinician get a true sense of the degree to which attempted therapeutic measures were effective (or ineffective). Additionally, patients may be questioned about their goals with respect to number and quality of bowel movements and the length of time spent in the bathroom. Some patients may arbitrarily assume that their bowel frequency/quality patterns are abnormal. Although there is no official or universally accepted definition of “normal,” a range from 3 stools per day to 3 stools per week is often cited.[36,37] Given the subjective nature of “normal stool patterns,” the Bristol Stool Scale is a useful tool to enable the clinician to get a more objective picture of the patient's bowel transit time.

Laboratory Tests

On the basis of the results of the patient history and physical and rectal examinations, laboratory and diagnostic tests may be warranted, including thyroid function tests; measurements of calcium, glucose, creatinine, and electrolytes; complete blood count; fecal occult blood; urinalysis; and diagnostic procedures aimed at assessing anorectal function (discussed later).[1,2,7,23,26] However, duplication of tests that were recently performed, as long as they were performed after the onset of symptoms, is rarely of any benefit.

Diagnostic Tests for Chronic Constipation

Diagnostic procedures are appropriate for patients who exhibit warning signs of organic disease and for those who experience persistent constipation that fails to respond to conservative treatment; they are also appropriate in instances when the primary care clinician suspects that the patient has a particular disorder.[7,10] Although most primary care clinicians do not routinely perform these diagnostic tests in their offices, some procedures, such as the balloon expulsion test (discussed later), can be performed in the primary care setting. Primary care clinicians may choose to ask the opinion of a gastroenterologist about which tests should be conducted in a given patient and, depending on the test, may perform the procedure themselves or have the test conducted at a specialty center. Alternatively, if the primary care clinician is comfortable in determining which test(s) are necessary but does not wish to perform the procedures in his or her office, a referral to the gastroenterologist for a procedure can be used to request that a specialist perform the appropriate test(s).[28]

The following paragraphs briefly describe the most commonly performed tests of anorectal function for patients with chronic constipation; their clinical utility is discussed, and sample test results are provided.

Rectal Balloon Expulsion Test

Because it is a simple, office-based screening test, balloon expulsion is often one of the first procedures performed in patients who do not respond to treatment with fiber and laxatives, and in whom pelvic floor dysfunction is suspected.[2] During this procedure, a latex balloon is inserted into the rectum, 50 mL of water or air is instilled into the balloon, and the patient is asked to expel the balloon into the toilet.[2] Failure to expel the balloon within 60 seconds suggests but does not confirm the presence of pelvic floor dysfunction. Although most patients with normal pelvic floor function can expel this device within 1 minute,[1] up to 10% of persons are unable to do so within this time.[38] Inability to expel the balloon within 3 minutes is more strongly suggestive of pelvic floor dysfunction. A few laboratories perform a more complex version of this procedure, using weights and a rectal catheter, as well as a balloon. However, it is unclear whether this provides more useful information (no data available).[2] See Figure 3.

Sample Report: Balloon Expulsion Test

Normal Result: With the patient seated on a commode, he or she was able to expel a 50-mL rectal balloon within ____ seconds.

Abnormal Result: With the patient seated on a commode, he or she was unable to expel a 50-mL rectal balloon in less than 2 minutes.

Figure 3. Sample report: Rectal balloon expulsion test.

Anorectal Manometry

Although it is more complex than the balloon expulsion procedure, anorectal manometry is one of the first tests performed in patients with suspected pelvic floor dysfunction.[2] It is also the procedure of choice for patients whose symptoms suggest the presence of adult-onset or short-segment Hirschsprung's disease (congenital megacolon).[7] Anorectal manometry assesses neuromuscular activity in the rectum and anal sphincter region, as well as rectal sensation, rectoanal reflexes, and rectal compliance.[1]

During this test, a special pressure-sensitive catheter is inserted into the anus.[7] High anal pressure at rest, accompanied by rectal pain, suggests the presence of an anal fissure.[2] Lack of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex generally results from enlargement of the rectum due to retained stool; however, it may also indicate Hirschsprung's disease.[2] Rectal hyposensitivity is usually caused by increased rectal capacity that results from prolonged stool retention, although it sometimes occurs secondary to a neurologic disorder.[2] Inappropriate contraction of the anal sphincter while the patient is at rest and bearing down suggests the presence of pelvic floor dysfunction.[2] See Figure 4.

Sample Report: Anorectal Manometry

Normal Result: With the patient in the left lateral recumbent position, during station pull-through technique, the upper border of the anal canal was identified 5 cm from the anal verge and extended to 1 cm. Mean resting pressure of the anal canal was approximately 65 mmHg. During voluntary contraction of the external anal sphincter, the patient was able to achieve maximal voluntary contraction pressures of 165 mmHg above baseline The patient was able to maintain 10 seconds of sustained contraction. With the use of 50 mL of balloon inflation in the rectum, a rectoanal inhibitory reflex was demonstrated. First sensation for rectal filling was normal at 40 mL, constant sensation was normal at 100 mL, and maximal tolerable volume was normal at 220 mL.

Abnormal Result: Same report as above, except that maximal tolerable volume was abnormal at 340 mL (indicating the presence of rectal hyposensitivity).

Figure 4. Sample report: Anorectal manometry.

Defecography

Defecography may be performed in patients with suspected pelvic floor dysfunction who have had an equivocal result during balloon expulsion or anorectal manometry testing.[2] It is also useful for patients who are suspected of having a structural abnormality of the rectum that impedes defecation.[2] Defecography is usually performed by a radiologist because it requires specialized equipment.

In this procedure, thickened barium (with the consistency of soft stool) is instilled into the rectum.[2,7] As the patient sits on a radiolucent commode, radiographic films or videos are taken during fluoroscopy while the patient rests, contracts the anal sphincter to defer a bowel movement, and then strains to defecate.[2,7] Defecography can determine whether complete emptying of the rectum has been achieved, can measure the anorectal angle and perineal descent, and can detect structural abnormalities, such as a rectocele or internal mucosal prolapse.[2,33] See Figure 5

Sample Report: Defecography

Indication: Constipation

Normal Result: Barium was instilled into the rectum. At rest, the anorectal angle was 105°. During evacuation, the anorectal angle increased to 135° and barium was easily expelled. No evidence of prolapse, intussusception, or rectocele was noted. Postevacuation films showed near-complete evacuation of barium.

Impression: Normal video defecography.

Abnormal Result: Barium was instilled into the rectum. At rest, the anorectal angle was 105°. During evacuation, the anorectal angle decreased to 95°. A large anterior rectocele of approximately 5.5 cm was noted. No evidence of prolapse or intussusception was seen. The patient stated that she had difficulty evacuating the barium. Postevacuation films revealed a large amount of barium remaining in the rectocele. The patient was advised to use an enema at home.

Impression: A 5-cm anterior rectocele was identified. Abnormal relaxation or inappropriate contraction of the puborectalis muscle, leading to a reduction in the anorectal angle during attempted defecation, may be a predisposing factor.

Figure 5. Sample report: Defecography.

Defecography has important limitations, including that patients may find the procedure embarrassing, and results must be interpreted carefully; abnormalities have been identified in up to 50% of persons with normal bowel function.[1,29] Accordingly, this procedure should be considered only as an adjunct to clinical and manometric assessment of anorectal function and should not be used as the first or the only test to evaluate pelvic floor dysfunction.[1]

Colonic Transit Test

Colonic transit is often the first test performed when the goal is to distinguish slow-transit constipation from normal-transit constipation.[2] It may also be used as a follow-up procedure for patients whose pelvic floor dysfunction has been corrected.[2] Major advantages of this test include the fact that it is safe, simple, noninvasive, and cost-effective.[27]

In this procedure, abdominal radiography is performed a specific number of days (eg, 5 days) after the patient swallows a capsule filled with radiopaque markers.[2,7] In normal controls, most markers are evacuated by day 5.[1] In patients with slow colonic transit, however, more than 20% of markers remain in the colon, usually in an equally scattered pattern.[1,2,7] Retention of markers in a specific area (eg, the rectosigmoid region such as the lower left colon and rectum) with sufficient transit through the remainder of the colon may indicate mechanical obstruction.[1,2] The Sitz-Mark (Konsyl Pharmaceuticals; Forth Worth, Texas) test is the proprietary name of a commonly performed colonic transit test.[2] More elaborate colonic transit procedures, involving ingestion of radiomarkers for several days and multiple radiographs, are warranted when additional information about regional colonic transit is desired.[26] See Figure 6.

Sample Report: Colonic Transit Test

Normal Result: The patient ingested a Sitz-Marker capsule (with 24 markers) on October 24 (day 0). Twenty-four hours later (day 1), an abdominal flat plat found that all 24 markers were scattered throughout the colon, predominantly on the right side. An abdominal flat plate on day 3 found that 16 markers remained: 1 in the ascending colon, 3 in the transverse colon, 2 in the area of the splenic flexure, 5 in the descending colon, and 5 in the rectosigmoid area. An abdominal flat plate on day 5 showed no markers remaining.

Impression: Normal Sitz-Marker study.

Abnormal Result: The patient reported ingesting a Sitz-Marker capsule (with 24 markers) on October 17 (day 0). Twenty-four hours later (day 1), an abdominal flat plate revealed that all 24 markers were present, predominantly in the right colon. At 72 hours (day 3), an abdominal x-ray revealed that 24 of 24 markers were present: 12 were located in the ascending colon, 10 in the transverse colon, and 2 in the region of the splenic flexure. At 120 hours (day 5), 20 of 24 markers were still present, generally equally distributed throughout the colon: 6 markers were present in the ascending colon, 6 in the transverse colon, 6 in the descending colon, and 2 in the rectosigmoid area.

Impression: This pattern is consistent with colonic inertia.

Figure 6. Sample report: Colonic transit test.

Barium Enema

Barium enema is another radiographic method by which the lumen of the colon can be visualized.[20,33,39] This test involves placing barium into the rectum and colon through a small tube. The barium coats the inside of the bowel, allowing visualization of the bowel lining.[40] This is a single-contrast method. The accuracy of this test is significantly increased by insufflating the colon with air at the same time (double-contrast method).

Barium enema, followed by radiography, is especially useful in children or young adults with suspected Hirschsprung's disease or idiopathic megarectum.[26] Barium enema can reveal structural abnormalities, obstructions, or evidence of bowel dilatation suggestive of an aganglionic segment.[23,33] See Figure 7.

Sample Report: Barium Enema

Normal Result:

Indication: Screening for colon cancer

On the spot image (abdominal x-ray), the loops of bowel appeared normal in caliber. Barium was instilled via the rectum, followed by insufflation with air. All areas of the colon were well visualized. Contrast was infused into the terminal ileum, which appeared normal. The mucosa appeared grossly normal, without evidence of diverticulosis or polyps. The patient evacuated the barium readily. Postevacuation films revealed only a slight amount of barium remaining in the right colon.

Impression: Normal double-contrast barium enema.

Abnormal Result:

Indications: Possible mass in the colon.

On the spot image (abdominal x-ray), the loops of bowel appeared normal in caliber. Barium was instilled via the rectum, followed by insufflation with air. All areas of the colon were well visualized. Contrast was infused into the terminal ileum, which appeared normal. In the ascending colon was a 3-cm polypoid filling defect that did not obstruct the lumen. Scattered diverticuli were seen in the sigmoid colon. The patient evacuated the barium easily. Postevacuation films revealed a small amount of barium remaining in the diverticula.

Impression: Lesion in ascending colon, nonobstructing. Sigmoid diverticulosis.h valign=“bottom” Recommendations: Colonoscopy to directly visualize the lesion in the ascending colon.

Figure 7. Sample report: Barium enema.

Because a balloon is placed in the rectum during instillation of barium, a rectal mass can be easily missed. Therefore, flexible sigmoidoscopy must be performed to enable visualization of the rectum and anal canal if the barium enema is being used as a screening test for colorectal cancer.[33]

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

Flexible sigmoidoscopy is used to visualize the lower colon, including the sigmoid colon, rectum, and anal canal.[7] Evaluation of the distal colonic mucosa through flexible sigmoidoscopy may provide evidence of long-term laxative use or may reveal melanosis coli or other lesions, such as solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, ischemia, inflammation, diverticulosis, or malignancy.[1] Flexible sigmoidoscopy can identify colonic dilatation and strictures and (combined with a barium enema) is a reasonable screening tool for patients at low risk for colorectal cancer.[7] See Figure 8.

Sample Report: Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

Normal Result:

Indication: Change in bowel habits with new-onset constipation.

The patient was placed in the left lateral recumbent position. Rectal examination was normal. The sigmoidoscope was carefully advanced to the splenic flexure. On insertion and withdrawal, there was no evidence of bleeding, inflammation, polyp formation, or diverticulosis. The mucosa appeared grossly normal. Retroflexion in the rectum was normal. The colon was decompressed and the scope removed. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was informed of the results.

Impression: Normal flexible sigmoidoscopy.

Recommendation: Treatment as indicated.

Abnormal Result

Indication: Change in bowel habits with new-onset constipation. The patient was placed in the left lateral recumbent position. Rectal examination was normal. The sigmoidoscope was carefully advanced to the splenic flexure. On insertion and withdrawal, there was no evidence of bleeding or polyp formation. Scattered diverticuli were noted in the sigmoid colon. Retroflexion in the rectum was normal. The colon was decompressed and the scope removed. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was informed of the results.

Impression: Sigmoid diverticulosis.

Recommendation: In this patient, a trial of fiber would be useful to help minimize straining, as this may decrease the likelihood of further formation of diverticuli.

Figure 8. Sample report: Flexible sigmoidoscopy

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy is used to visualize the entire colonic mucosa (not just the lower colon, as is the case with flexible sigmoidoscopy), and to identify ulcers, ischemia, foreign bodies, diverticulosis, fissures, and so forth.[7] Because of its ability to detect polyps and other important but often incidental lesions, it is the examination of choice in patients older than age 50 and in those with warning signs for organic diseases, including iron-deficiency anemia, hemoccult-positive stools or a first-degree relative with colon cancer.[7,26] In the United States, colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of deaths related to cancer, behind lung cancer.[41] The American Cancer Society recommends that, in average-risk individuals (eg, those with no family history of cancer), screening for colon cancer begin at age 50 (in both men and women). If screening results are normal, colonoscopy is then recommended every 10 years. Individuals with particular risk factors (eg, personal or family history of colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps, personal history of chronic inflammatory bowel disease) should undergo screening at an earlier age and/or more often.[42] See Figure 9

Sample Report: Colonoscopy

Normal Result:

Indication: Constipation.

Patient History: No history of weight loss or anemia; no family history of colorectal cancer.

The patient was placed in the left lateral decubitus position, and a digital rectal exam was performed, which was normal. The colonoscope was inserted into the anus and under direct visualization was advanced to the cecum, identified by the appendiceal orifice and the ileocecal valve, both of which appeared grossly normal. The terminal ileum was intubated and appeared grossly normal. On insertion and withdrawal, there was no evidence of bleeding, inflammation, or polyp formation. Retroflexion in the rectum revealed small, nonbleeding internal hemorrhoids. No biopsy specimens were taken. The colon was then decompressed and the scope removed. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was informed of the results.

Impression: Small internal hemorrhoids.

Recommendation: Repeat colonoscopy in 10 years for screening purposes, unless new symptoms develop earlier.

Abnormal Result:

Indication: Guaiac-positive stool.

Patient History: No history of anemia or unintentional weight loss. No family history of colorectal cancer. No previous colonoscopy. The patient was placed in the left lateral decubitus position, and a digital rectal exam was performed. The colonoscope was inserted into the anus and under direct visualization was advanced to the cecum, identified by the appendiceal orifice and the ileocecal valve. Two sessile polyps with bleeding were found in the descending colon, one at 45 cm and one at 60 cm from the anal verge. The polyps each measured about 5 mm. The polyp at 45 cm was completely removed with cold snare technique (jar #2); the polyp at 60 cm was removed with hot snare technique (jar #1). Resection and retrieval were complete. A fungating, ulcerated, friable, nonobstructing mass was found in the rectum. The mass measured 3 cm in length and took up approximately half the circumference of the rectum. No bleeding was present. This was removed with a cold biopsy forceps and sent for biopsy testing for pathology (jar #3). Just proximal to the large rectal mass was a 7-mm polyp. This polyp was at 9 cm from the anal verge and was left in place. Digital rectal exam revealed a firm rectal mass, the distal edge palpated 6 cm from the anal verge. The mass was noncircumferential and was located predominantly on the posterior bowel wall. The patient tolerated the procedure well.

Impression: Two 5-mm polyps in the colon. Resected and retrieved. Mass in rectum that is likely malignant.

Recommendation: Staging CT with contrast (via the intravenous and oral routes). Consider endoscopic ultrasound to assess depth of invasion. Surgical consult.

Figure 9. Sample report: Colonoscopy.

Special Categories and Additional Discussion

Patients Who Fail to Respond to Available Medical Therapy

Although a full review of all treatment options for patients with constipation is beyond the scope of this article, one special category warrants mention – that of patients with significant colonic inertia who fail all available medical therapy. These patients are typically young women who may have a bowel movement every 7–28 days. Diagnostic evaluation has typically included a normal colonoscopy, a normal anorectal manometry with balloon expulsion test, a normal video defecography, and testing to ensure that there is no evidence of a motility disorder in the upper gastrointestinal tract (ie, normal gastric emptying scan and normal small bowel follow-through or normal antroduodenal manometry). A sitz marker study has confirmed delayed transit. If reasonable trials of all medications fail, then surgery may be indicated. Current recommendations are that if surgery is indicated, total colectomy (not partial) be performed with ileorectostomy (also called ileoproctostomy). Patients need to be aware that they will then likely have frequent daily bowel movements, up to 6–8 per day.

When to Refer a Patient for Biofeedback Therapy

Patients with pelvic floor dyssynergia are best treated with biofeedback therapy because medical therapy is not effective in these patients. It is important to find a physical therapist who is well versed in pelvic floor disorders and who has an interest in these patients in order to maximize a response. During biofeedback, a probe is inserted into the anorectal area and patients are taught to properly coordinate (relax and contract) the muscles in their pelvic floor. As the patient performs the appropriate maneuvers, he/she can monitor the progress on a television screen. Most programs have patients come in for weekly or every-other-week sessions until they have learned to properly coordinate their pelvic floor muscles.

What to Do With Abnormal Results

One question that is often raised by primary care physicians is when to refer after a test returns with abnormal results. Unfortunately, there is no set answer to this question. In most situations, if there are no warning signs by history or physical examination (ie, no history of gastrointestinal bleeding, anemia, unintentional weight loss, etc.), and mechanical obstruction of the colon has been ruled out (ie, normal colonoscopy or normal barium enema and flexible sigmoidoscopy), then the primary-care physician should feel comfortable treating the patient. For example, if a young patient has evidence of colonic inertia, then medical therapy with a polyethylene glycol solution or 5-HT4 agonist, such as tegaserod, may be appropriate. If there is evidence of pelvic floor dysfunction on anorectal manometry, then referral to a physical therapist should take place. Certainly, if the patient fails to respond to therapy, or if there are warning signs on history or examination, then referral to a gastroenterologist is warranted.

Conclusion

Effective communication between primary care clinicians and gastroenterologists is critical to the optimal care of patients with constipation. Primary care clinicians can take numerous steps to maximize the benefits of the referral process, including familiarizing themselves with the purposes of various diagnostic tests of colonic and anorectal function and determining which procedures can be performed routinely in their offices vs those that would best be handled through a referral for a procedure. They can also customize a referral form to optimally communicate the patient's medical background and describe what they are striving to achieve through the referral process. Finally, primary care clinicians can develop a network of long-term working relationships with local gastroenterologists who are interested in consulting and who specialize in the diagnosis and treatment of various chronic disorders, such as constipation.

Table 1.

Rome II Diagnostic Criteria for Constipation[13]

| Two or more of the following symptoms for at least 12 weeks (not necessarily consecutive) in the preceding 12 months: |

|

| Loose stools are not present, and criteria for irritable bowel syndrome are insufficient. |

Contributor Information

Brian E. Lacy, GI Motility Laboratory, Division of Gastroenterology, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire.

Stephen A. Brunton, Cabarrus Family Medicine Residency, Charlotte, North Carolina.

References

- 1.Rao SS. Constipation: evaluation and treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:659–683. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(03)00026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1360–1368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Clinical epidemiology of chronic constipation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:525–536. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198910000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., III Functional constipation and outlet delay: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:781–790. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90896-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandler RS, Drossman DA. Bowel habits in young adults not seeking health care. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:841–845. doi: 10.1007/BF01296706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talley NJ, Jones M, Nuyts G, Dubois D. Risk factors for chronic constipation based on a general practice sample. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1107–1111. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arce DA, Ermocilla CA, Costa H. Evaluation of constipation. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:2283–2290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talley N, O'Keefe E, Zinsmeister A, Melton LJ., III Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the elderly: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:895–901. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koch A, Voderholzer WA, Klauser AG, Muller-Lissner S. Symptoms in chronic constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:902–906. doi: 10.1007/BF02051196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiller LR. Review article: the therapy of constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:749–763. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Irvine EJ, Muller-Lissner SA. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. 1999;45(suppl II):II43–II47. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drossman DA, Whitehead WE, Camilleri M. Irritable bowel syndrome: a technical review for practice guideline development. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:2120–2137. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.agast972120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Talley NJ, et al. ROME II: a multinational consensus document on functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 1999;45(suppl II):II1–II81. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glia A, Lindberg G. Quality of life in patients with different types of functional constipation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:1083–1089. doi: 10.3109/00365529709002985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irvine EJ, Ferrazzi S, Pare P, Thompson WG, Rance L. Health-related quality of life in functional GI disorders: focus on constipation and resource utilization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1986–1993. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Epidemiology of constipation in the United States. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:1–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02554713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh G, Kahler K, Bharathi V, Mithal A, Omar M, Triadafilopoulos G. Adults with chronic constipation have significant healthcare resource utilization and costs of care. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:S227. [Abstract #701] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin BC, Barghout V. National estimates of office and emergency room constipation-related visits in the United States [abstract] Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(10 suppl):s244. Abstract 754. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray M. Reducing waits and delays in the referral process. Fam Pract Manag. 2002;9:39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Locke GR, III, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. AGA technical review on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1766–1778. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker BL. Strategies for managing referrals…without losing your patients. Fam Pract Manag. 1994;1:109–111. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shenkel RC. Building rapport with consultants: a matter of economics. Fam Pract Manag. 1996;3:36–38. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borum ML. Constipation: evaluation and management. Primary Care. 2001;28:577–590. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(05)70054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bharucha AE, Philips SF. Slow-transit constipation. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2001;4:309–315. doi: 10.1007/s11938-001-0056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knowles CH, Martin JE. Slow transit constipation: a model of human gut dysmotility. Review of possible aetiologies. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2000;12:181–196. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2000.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wald A. Constipation. Med Clin North Am. 2000;84:1231–1246. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camilleri M, Ford MJ. Review article: colonic sensorimotor physiology in health, and its alteration in constipation and diarrhoeal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:287–302. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Locke GR, III, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement: guidelines on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1761–1766. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wofford SA, Verne GN. Approach to patients with refractory constipation. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2000;2:389–394. doi: 10.1007/s11894-000-0038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curry CE, Butler DM. Constipation. In: Berardi RR, DeSimone EM, Newton GD, et al., editors. Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs: An Interactive Approach to Self-Care. 14th ed. Washington, DC: APhA Publications; 2004. pp. 367–403. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Passmore AP. Economic aspects of pharmacotherapy for chronic constipation. PharmacoEconomics. 1995;7:14–24. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199507010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gattuso JM, Kamm MA. Review article: the management of constipation in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1993;7:487–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1993.tb00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faigel DO. A clinical approach to constipation. Clin Cornerstone. 2002;4:11–21. doi: 10.1016/s1098-3597(02)90002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:920–924. doi: 10.3109/00365529709011203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heaton KW, O'Donnell LJ. An office guide to whole-gut transit time. Patients' recollection of their stool form. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;19:28–30. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199407000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tucker DM, Sandstead HH, Logan GM, Jr, et al. Dietary fiber and personality factors as determinants of stool output. Gastroenterology. 1981;81:879–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Connell AM, Hilton C, Irvine G, Lennard-Jones JE, Misiewicz JJ. Variation of bowel habit in two population samples. BMJ. 1965;5470:1095–1099. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5470.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prather CM. Subtypes of constipation: sorting out the confusion. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2004;4(suppl 2):S11–S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stanghellini V, Tosetti C, Barbara G, De Giorgi R, Salvioli B, Corinaldesi R. The continuing dilemma of dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14(suppl 3):23–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orkin BA. Milwaukee, Wis: International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders; 1993. Physiological Testing of the Colon, Rectum and Anus. Tests for Bowel Dysfunction; IFFGD Publication No. 111. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayo Clinic Staff. Colorectal cancer. Mayo Clinic Web site

- 42.ACS guidelines for colorectal cancer screening. American Cancer Society Web site