A 26-year-old female presented to Kijabe Mission Hospital with a diffuse rash and dyspnea.

The patient had been well until 5 days prior to admission when a pruritic rash began on her face, neck, and upper chest, accompanied by fever. The rash spread to involve her entire thorax, arms, and proximal thighs. One day prior to presentation, cough and dyspnea developed.

Past medical history: The husband provided the history because the patient was in extremis. He reported no known medical problems or previous hospitalizations. She had not been tested for HIV infection.

Medications: The patient was not using any regular medication but had applied calamine lotion to the rash.

Social history: The patient was married. She lived in Mai Maihu, a truck-stop town in the Great Rift Valley of Kenya. The town is known to have a high prevalence of HIV infection.

Physical examination: The vital signs were blood pressure 130/70 mm Hg, pulse 120/min, respiratory rate 44/min, temperature 36.0 degrees Celsius, and oxygen saturation 73% on room air. The patient was in respiratory distress, using accessory muscles and coughing. Oral thrush was present. Auscultation of the chest revealed a regular tachycardia and diffuse rales throughout both lung fields. Innumerable small papules and fluid-filled vesicles (approximately 2-5 mm in diameter) were present in the above described distribution. Most of the vesicles were closed, although some were open and excoriated.

Laboratory evaluation: A rapid test for HIV was positive.

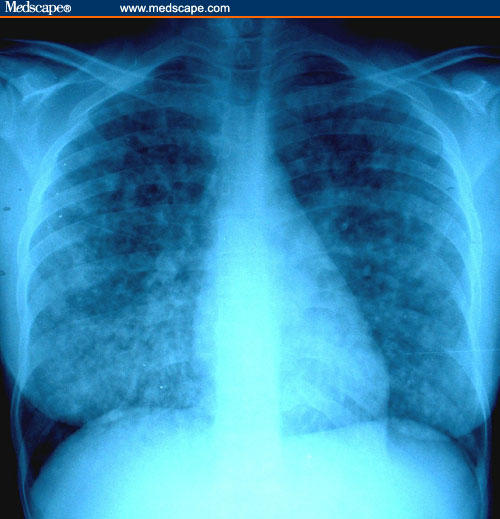

Chest x-ray: Diffuse, confluent bilateral nodular infiltrates

Hospital course: The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. Despite high-flow oxygen supplementation via a non-rebreather mask, the saturation did not rise above 80%. Treatment with anti-infective therapy was instituted, but her condition rapidly deteriorated. Hemoptysis developed. The patient was deemed too ill for the hospital's only ventilator. No other treatment options were available. The patient expired less than 24 hours after admission.

What is the unifying diagnosis?

The diffuse vesicular rash is characteristic of disseminated varicella infection, although a few agents (see below) may mimic this disease. The pulmonary manifestations are consistent with secondary involvement of the lung.

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is a frequent source of morbidity in HIV and other immunocompromised patients. Although pneumonia, encephalitis, and secondary bacterial infection may develop in immunocompetent adults and children, visceral involvement is much more likely in immunodeficient states.[1] In one African series, 91% of patients with a history of herpes zoster were HIV-positive.[2]

Primary infection with VZV usually manifests as chickenpox or may be asymptomatic. Reactivation disease presents as herpes zoster, a painful rash localized in a dermatomal distribution.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (seen in a different patient), or reactivation disease in the distribution of the first branch of the fifth cranial nerve, is a particularly dangerous subset of this entity, also more common in HIV-infected patients, and may result in vision loss through corneal damage or central retinal necrosis.

Extracutaneous and visceral involvement of either primary or reactivation VZV infection predominates in the central nervous system, liver, or lung. Neurologic manifestations include encephalitis and stroke. Hepatitis is rare but carries a significant risk of death.

Varicella pneumonitis is also commonly fatal. As in this case, pulmonary complaints occur within the first week, and hemoptysis has been described. The chest x-ray often shows bilateral, coalescing opacities; the nodules may become calcified over time. This patient displayed severe shunt physiology with little response to high-flow oxygen. The case-fatality rate is high (10% to 30%), even among immunocompetent patients.

The diagnosis can often be made clinically, based on characteristic skin lesions.[3] Primary varicella commences, as in this instance, around the face and neck and spreads centripetally, with lesions in different stages of development. Zoster begins and usually remains confined to a single dermatome or possibly two, although subsequent dissemination may occur. The differentiation between primary varicella and reactivation disseminated zoster can be difficult, especially if the latter did not start in a clearly defined dermatome prior to spread. If the diagnosis is in doubt, samples from ulcers may be sent for fluorescent antibody staining, a test that is not available at Kijabe Hospital. This procedure helps rule out disseminated herpes simplex infection. Smallpox also produces a vesicular rash, as can vaccinia following immunization (generalized vaccinia).

Only an HIV test was ordered because it was not believed that additional laboratory investigations would have significantly altered diagnosis or management. In our Kenyan setting, the costs and utility of interventions must always be weighed. The charges for an HIV spot test and a chest x-ray are 2.65 and 8.65 USD, respectively. For the average family surrounding the hospital, at least 1 week's earnings would be required to pay these costs alone.

Disseminated herpes simplex cannot be ruled out in this case. The clinician in the resource-poor setting relies upon clinical presentation and known epidemiology to make a diagnosis and proceed with therapy.

Standard treatment of varicella pneumonia involves intravenous acyclovir and supportive care, including intubation and mechanical ventilation if necessary. One report described improved outcomes in a small number of patients treated with steroids.[4]

As described in the case presentation, the patient was admitted to the ICU and administered high-flow oxygen. She was also given high-dose donated oral acyclovir; intravenous acyclovir is not available at our institution. Oral acyclovir does not produce adequate blood levels for treatment of disseminated infection. Therefore, because appropriate antiviral therapy could not be ensured, steroids were withheld.

The case also demonstrates the difficult resource utilization decisions that must be made in many African hospitals. The dismal prognosis, in light of the fact that the hospital had only 1 ventilator, prompted the decision not to intubate.

Figure 1.

Papular and vesicular facial rash.

Figure 2.

Abdominal rash. The patient had applied calamine lotion at home. Note that the rash is not confined to any one dermatome.

Figure 3.

Chest radiography revealed diffuse, confluent bilateral nodular opacities.

Figure 4.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus.

References

- 1.Albrecht MA. Clinical features of varicella-zoster virus infection: chickenpox. In: Rose BD, editor. UpToDate. Wellesley, Mass: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colebunders R, Mann JM, Francis H, et al. Herpes zoster in African patients: a clinical predictor of human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:314–318. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erlich KS, Safrin S. San Francisco: HIVInSite, University of California; Varicella-Zoster Virus and HIV. February 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mer M, Richards GA. Corticosteroids in life-threatening varicella pneumonia. Chest. 1998;114:426–431. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]