Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) may manifest typically with heartburn and regurgitation or atypically as laryngitis, asthma, cough, or noncardiac chest pain. The diagnosis of these atypical manifestations may be difficult for primary care physicians because most patients do not have heartburn or regurgitation. Diagnostic tests have low specificity and it is difficult to establish a cause-and-effect association between GERD and atypical symptoms. Response to aggressive acid suppression is often the most commonly employed initial tool to indicate GERD etiology in a patient with atypical symptoms.

Symptoms Associated With GERD

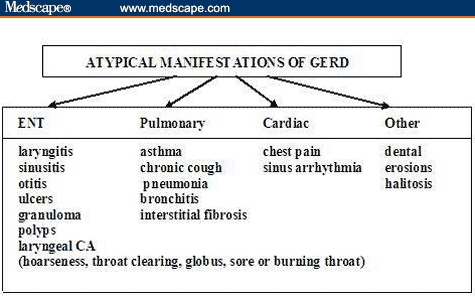

GERD commonly presents as heartburn and regurgitation, experienced daily by 7% and monthly by up to 40% of the US population.[1] In addition to heartburn and regurgitation, GERD may present with other less typical symptoms. Most common “atypical” manifestations may include ear, nose, and throat (ENT); pulmonary (chronic cough or asthma); or cardiac (noncardiac chest pain) symptoms (Figure 1).[2–5] Patients with atypical manifestations may not have concomitant complaints of heartburn. Classic reflux symptoms are absent in 40% to 60% of asthmatics, in 57% to 94% of patients with ENT complaints,[4,5] and in 43% to 75% of patients with chronic cough in whom reflux is suspected as the etiology. Due to the latter, many patients may not be appropriately diagnosed initially. Thus, GERD should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with atypical symptoms,[3,4] especially when alternative diagnoses are excluded.

Figure 1.

Atypical GERD. Key: ENT = ear, nose, throat; CA = cancer

Two mechanisms have been proposed to explain atypical symptoms of GERD: microaspiration of gastric contents and vagally mediated events.[3,4] A disturbance in any of the normal protective mechanisms may allow direct contact of noxious gastroduodenal contents with the larynx or the airway, resulting in laryngitis, chronic cough, or asthma. As to indirect mechanisms, embryologic studies show that the esophagus and bronchial tree share a common embryologic origin and neural innervation via the vagus nerve. Acidification of the distal esophagus can stimulate acid-sensitive receptors, resulting in noncardiac chest pain, cough, or bronchoconstriction and asthma.

Asthma

Many pulmonary conditions are associated with GERD (Figure 1); the strongest association appears to be with asthma.[6,7] Of the 15 million persons in the United States with asthma, 50% to 80% may also have GERD. Most patients with asthma complain of coexisting heartburn,[7] and up to 75% of patients have excess esophageal acid exposure by pH monitoring.[7] Although many patients with refractory asthma may improve on acid-suppressive therapy, the cause-and-effect relationship between asthma and GERD is difficult to establish; this is because either condition may induce the other. Asthma attacks can cause esophageal reflux of gastric contents by creating a negative intrathoracic pressure, overcoming the lower esophageal sphincter barrier.[7] Alternatively, gastroesophageal reflux – either by direct aspiration or indirectly by stimulating the distal esophageal sensory vagal nerve – may induce bronchospasm and asthma. Additionally, it is recognized that asthma medications may promote GERD. Theophylline, beta 2-agonists, and even prednisone may increase esophageal exposure to acid reflux by affecting protective mechanisms against GERD.[8]

The patient's medical history is the most important clue in diagnosing GERD as the potential etiologic factor in asthmatics. Indeed, certain “clues” can be helpful in identifying GERD-related asthma. Patients who should be suspected of having GERD include those with nocturnal cough and worsening asthma symptoms after eating big meals, drinking alcohol, or being in the supine position; those with asthma presenting initially in adulthood; and those who have poor control of asthma symptoms with their usual asthma medications. Additionally, symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation before the onset of asthma may suggest reflux as the causal factor.

Chronic Cough

Chronic cough (cough duration greater than 3 weeks) accounts for up to 38% of referrals to pulmonary physicians and is one of the most common clinical presentations in primary care practice. GERD, along with postnasal drip and asthma, is 1 of the 3 most common causes of chronic cough in all age groups.[9,10] More than 1 etiologic factor may be the cause of chronic cough in many patients. Similar to asthma, a cause-and-effect association is often difficult to establish because chronic cough can induce GERD[9,10] as well as be caused by it.

GERD-related cough occurs predominantly during the day and in the upright position. It is often nonproductive and long-standing in nature. Cough may be the sole manifestation of GERD in more than 50% of patients,[9] with many denying symptoms of heartburn or regurgitation. GERD should be suspected in patients with cough whose symptoms have been chronic, not smokers, not on any cough-inducing medications (such as ACE inhibitors), with normal chest x-ray, and in those in whom there is no evidence of asthma or postnasal drip.

Reflux Laryngitis

There is increasing evidence that GERD may be associated with chronic laryngeal signs and symptoms.[4,5] This is often referred to as “reflux laryngitis,” “ENT reflux,” or recently as “laryngopharyngeal reflux.” Laryngeal symptoms often associated with GERD may include hoarseness, throat clearing, cough, sore or burning throat, dysphagia, and globus. Hoarseness is caused by GERD in an estimated 10% of all cases. Chronic laryngitis and difficult-to-treat sore throat are associated with acid reflux in as many as 60% of patients.[4] GERD is the third leading cause of chronic cough (after sinus problems and asthma), accounting for 20% of cases.[9,10] Globus sensation (a feeling of choking or a lump in the throat more prominent between meals and generally disappearing at night) may be caused by GERD in 25% to 50% of cases. The most common mechanism for laryngeal irritation due to GERD is via direct contact with the gastroduodenal contents.[4] Recent studies show that pepsin and conjugated bile acids in acidic pH ranges result in laryngeal tissue inflammation, whereas nonacid exposure of any gastroduodenal agents does not cause injury.[11]

Clinically, patients are initially evaluated by primary care physicians and subsequently referred to ENT physicians for laryngoscopy. Laryngoscopic evaluation is usually the initial test in patients suspected of having GERD. Normal laryngeal tissue is often smooth and glistening in nature; however, GERD may be responsible for causing laryngeal pathology such as ulcerations, vocal cord nodules, granuloma, or even leukoplakia and cancer. Many laryngeal signs have been attributed to GERD, including erythema and edema of the posterior larynx, vocal cord polyps, and granuloma and subglottic stenosis. However, most signs are not specific for GERD and may also occur as a result of other laryngeal irritants, such as smoking, alcohol, postnasal drip, viral illness, voice overuse, or environmental allergens. This may explain why many patients with laryngeal signs do not respond to GERD therapy. Recent studies suggest that laryngeal abnormalities involving the vocal cords and medial arytenoid walls may be more specific for GERD, suggesting that the subjective laryngeal signs of erythema and edema currently in common use should be abandoned in an effort to increase confidence in GERD diagnosis.[4]

Chest Pain

Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with chest pain exhibit normal or insignificant cardiac catheterization findings and are classified as having “noncardiac” chest pain.[12,13] GERD may be the most common cause of noncardiac chest pain. However, spastic esophageal motility disorders such as nutcracker esophagus or diffuse esophageal spasm may also be important etiologies for patients' symptoms once GERD is excluded. Recent data suggest that GERD may account for symptoms in 25% to 55% of patients with noncardiac chest pain.[12] Direct contact of the esophageal mucosa with gastroduodenal agents such as acid and pepsin is the most likely cause of these symptoms.[12,13]

Initially, it may be difficult to distinguish GERD-related chest pain from angina. GERD-related chest pain can be squeezing or burning in nature, substernal in location, and may radiate to the back, neck, jaws, or arms. The pain may be worse after meals and wake the patient from sleep. Exercise may induce GERD, resulting in chest pain, which can be indistinguishable from chest pain due to coronary disease. Symptoms may last for minutes or hours and are often relieved by antacids or acid-suppressive agents. Similar to GERD-related asthma patients, many individuals may also report a history of heartburn and regurgitation; however, up to 20% of patients may have silent reflux.[12] Given the serious dilemma of distinguishing GERD-related chest pain from coronary disease, the clinician should always rule out the latter before considering the former.

Diagnostic Tests

Commonly employed diagnostic tests for the detection of GERD include barium swallow, endoscopy, and 24-hour pH monitoring. However, based on a patient's history, empiric therapy is usually initiated without the need for any testing.[14] Testing is usually indicated in patients with persistent symptoms despite therapy, those with warning signs (ie, dysphagia, weight loss, bleeding), prior to fundoplication, or in those patients with long-standing GERD in order to rule out Barrett's esophagus.

Patients with atypical GERD symptoms usually have a low prevalence of endoscopic esophagitis. Most studies report only mild esophagitis in 10% to 30% of patients with atypical GERD.[2,4] This is in contrast to cases of typical GERD, in which esophagitis may be present in up to 50% of patients. Once considered to be the gold standard for detecting esophageal acid exposure, 24-hour pH monitoring suffers from poor sensitivity (70%-80%). The false-negative rate for this test (the patient has the disease by either prior pH monitoring or endoscopy) may range from 20% to 50%.[15] Therefore, a negative test may not exclude the diagnosis of GERD in patients with atypical complaints. More important, a positive test does not confirm that GERD is the etiology for the atypical symptoms; the cause-and-effect relationship is usually best established with sustained response to acid-suppressive therapy.[4,12] (However, one has to be mindful of placebo response when response to therapy is judged to be the gold standard.) Therefore, diagnostic tests for atypical GERD should usually be reserved for those patients who are unresponsive to therapy or have other indications for testing. It is now believed that in the majority of patients who continue to have symptoms despite aggressive acid suppression, GERD may not be the cause of their symptoms or laryngeal findings. The role of nonacid reflux continues to be questioned in this group of unresponsive patients. Impedance/pH monitoring allows for detection of acid as well as nonacid liquid or gas reflux events and may increase the sensitivity of GERD diagnosis in this group of patients. However, the overdiagnosis of GERD in many patients with atypical symptoms may be the most important limitation of any of the currently available diagnostic tests.

Treatment

Patients with atypical GERD are often more difficult to treat, and as a group, they have an unpredictable response to acid-suppressive therapy. The latter is most likely due to overdiagnosis of the condition. Response of these patients to therapy may represent the true prevalence of GERD in this population; GERD may be only 1 of several etiologies causing these patients' symptoms and signs. Other such etiologies may include coexistence of asthma, GERD, cough, postnasal drip, and other aggressive factors, such as alcohol and smoking. Thus, given the poor specificity of diagnostic testing, response to empiric therapy is currently the “gold standard” for diagnosing GERD in this group of patients. There are currently no accepted protocols for the most cost-effective treatment strategy for patients with atypical GERD. At best, histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) usually produce only mild-to-moderate improvement in symptoms.[4,12] Although not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of atypical GERD, recent studies recommend using the more effective proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), often given twice daily.[16–18] Clinical response rates ranging from 60% to 98% have been reported with medical therapy.[4,12] This wide range in treatment response is most likely due to differences in subspecialty practices and differences in patient populations.

Previous studies using H2RAs have produced only mild-to-moderate improvements, at best.[5,19] As mentioned, recent studies have used the more effective acid-suppressive agents, the PPIs.[20–23] However, due to lack of consensus, most studies employed PPIs at varying doses and different durations of treatment. Because human studies suggest that nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux is more common in this group of patients,[24] the majority of studies used nocturnal dosing of PPIs, increased to twice-daily dosing in nonresponders. The PPIs are commonly given before meals in most studies. For example, Kamel and colleagues[19] and Wo and colleagues[21] used 40 mg of omeprazole at bedtime, and increased the dose to 40 mg twice daily in nonresponders after 2 months of treatment. However, each study reported a different rate of treatment response. (Kamel and colleagues found a 92% response rate, whereas Wo and colleagues reported a 67% response rate in their patients.) Our recent data confirm the response rate reported by the latter group, finding a 52% symptomatic response rate with twice-daily dosing of PPIs at 4 months.[25] On the basis of these studies, it is generally accepted that PPIs should be used at twice-daily dosing for empiric therapy of patients with ENT signs and symptoms.[2,4]

Meanwhile, recent placebo-controlled studies in this area[26–30] show that aggressive PPI therapy is equivalent to placebo in symptom relief for throat complaints. Such findings once again highlight the complexity of the association between GERD and extraesophageal symptoms and reflux. Because many individuals have GERD, the specific association between extraesophageal symptoms and GERD is often difficult to establish.

Surgical intervention is usually less effective in patients with atypical GERD than in patients with typical GERD symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation.[4,12] This again reflects the multifactorial nature of atypical GERD symptoms in many patients. Recent studies advise caution regarding the use of fundoplication in patients with atypical GERD who are unresponsive to PPI therapy.[31]

Studies show that response to surgical fundoplication is dependent on medical response to PPIs.[32–34] Recently, Swoger and colleagues[32] reported no benefit of fundoplication in patients with chronic laryngitis suspected to be GERD-related and who did not respond to twice-daily PPIs. Similarly, So and colleagues[33] studied 150 consecutive patients after fundoplication and found that only 56% had relief of atypical symptoms, whereas typical heartburn symptoms resolved in 93%. Furthermore, the only preoperative predictors of relief of atypical symptoms were prior clinical response to pharmacologic acid suppression and abnormal hypopharyngeal pH results. More specifically, a recent uncontrolled case series[34] evaluating the outcome of patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux reported 84% symptom improvement post fundoplication. However, this study again demonstrated a poor outcome in those patients previously unresponsive to PPI therapy.

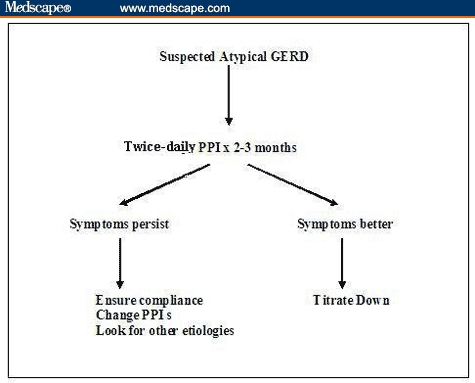

A potential treatment algorithm for atypical GERD is shown in Figure 2. Initial empiric therapy with twice-daily PPIs for 2–3 months is generally recommended.

Figure 2.

Treatment algorithm for atypical GERD.

For patients with laryngitis, longer treatment duration may be needed for resolution of all laryngeal inflammation. In patients with asthma, up to 3 months of treatment may be required to see improvement in bronchial symptoms.[4] However, many patients with atypical symptoms may report a partial response by 6–8 weeks of therapy. For those patients who have minimal or no improvement in their symptoms by 4 months of twice-daily PPI therapy, 24-hour pH/impedance monitoring on therapy may help identify that small subgroup that continues to have abnormal esophageal acid or nonacid exposure. However, in the majority of patients, lack of response is an indication that GERD is most likely not an etiologic factor in their atypical symptoms. In this subgroup of patients, other causes of symptoms should be investigated.

Concluding Remarks

GERD and extraesophageal symptoms have a complex relationship. In many patients who have extraesophageal symptoms, reflux of acid or nonacid gastroduodenal contents may be a causal factor. However, in many others, although GERD may be implicated, reflux disease may play a minimal role. The current diagnostic tests lack specificity to help unravel this complex association. Thus, empiric therapy is currently the most specific tool to determine whether reflux disease is playing a significant role in patients' extraesophageal symptoms. The current recommendation in such patients is therapy with PPIs for at least 2–3 months. In those who respond to therapy, tapering the degree of acid suppression is the next step, whereas in those unresponsive to PPI therapy, causes other than GERD should be sought.

Readers are encouraged to respond to George Lundberg, MD, Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eye only or for possible publication via email: glundberg@medscape.net

References

- 1.Locke GR, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population based study in Olmstead County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448–1456. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richter JE. Atypical presentation of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 1997;8:75–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaker R. Protective mechanisms against supraesophageal GERD. Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:S3–S8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaezi MF, Hicks DM, Abelson TI, Richter JE. Laryngeal signs and symptoms and GERD: a critical assessment of cause and effect association. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:333–344. doi: 10.1053/s1542-3565(03)00177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koufman JA. The otolaryngologic manifestation of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Laryngoscope. 1991;101(suppl 53):1–78. doi: 10.1002/lary.1991.101.s53.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sontag SJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and asthma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:S9–S30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harding SM. Recent clinical investigations examining the association of asthma and gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Med. 2003;115:S39–S44. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazenby JP, Guzzo MR, Harding SM, et al. Oral corticosteroids increase esophageal acid contact times in patients with stable asthma. Chest. 2002;121:625–634. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.2.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irwin RS, Richter JE. Gastroesophageal reflux and chronic cough. Am J Med. 2000;95:S9–S14. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(00)01073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irwin RS, Curley FJ, French CL. Chronic cough. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:640–647. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.3.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adhami T, Goldblum JR, Richter JE, Vaezi MF. The role of gastric and duodenal agents in laryngeal injury: an experimental canine model. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2098–2106. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richter JE. Chest pain and gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:S39–S41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ockene IS, Shay MT, Alpert JS, et al. Unexplained chest pain in patients with normal coronary arteriograms. A follow-up study of functional status. N Engl J Med. 1980;30:1249–1252. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198011273032201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devault KR, Castell DO. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1434–1442. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.1123_a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaezi MF, Schroeder PL, Richter JE. Reproducibility of proximal probe pH parameters in 24-hour ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:825–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw GY, Searl JP. Laryngeal manifestations of GER before and after treatment with omeprazole. South Med J. 1997;90:1115–1122. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199711000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wo JM, Grist WJ, Gussack G, et al. Empiric trial of high-dose omeprazole in patients with posterior laryngitis: A prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2160–2165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaezi MF, Hicks DM, Ours TM, Richter JE. ENT manifestation of GERD: A large prospective study assessing treatment outcome and predictors of response. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:A636. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamel PL, Hanson D, Kahrilas PJ. Omeprazole for the treatment of posterior laryngitis. Am J Med. 1994;96:321–326. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaw GY, Searl JP. Laryngeal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux before and after treatment with omeprazole. South Med J. 1997;90:1115–1122. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199711000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wo JM, Grist WJ, Gussack G, et al. Empiric trial of high-dose omeprazole in patients with posterior laryngitis: A prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2160–2165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metz DC, Childs ML, Ruiz C, Weinstein GS. Pilot study of the oral omeprazole test for reflux laryngitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;116:41–46. doi: 10.1016/s0194-5998(97)70350-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanson DG, Kamel PL, Kahrilas PJ. Outcomes of antireflux therapy for the treatment of chronic laryngitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1995;104:550–555. doi: 10.1177/000348949510400709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamel PL, Hanson D, Kahrilas PJ. Omeprazole for the treatment of posterior laryngitis. Am J Med. 1994;96:321–326. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park W, Hicks DM, Khandwala F, et al. Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR): Prospective cohort study evaluating optimal dose of PPI therapy and pre-therapy predictors of response. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1230–1238. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000163746.81766.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noordzij JP, Khidr A, Evans BA, et al. Evaluation of omeprazole in the treatment of reflux laryngitis: a prospective, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind study. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:2147–2151. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200112000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eherer AJ, Habermann W, Hammer HF, Kiesler K, Friedrich G, Krejs GJ. Effect of pantoprazole on the course of reflux associated laryngitis: a placebo-controlled double-blind crossover trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:462–467. doi: 10.1080/00365520310001860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steward DL, Wilson KM, Kelly DH, et al. Proton pump inhibitor therapy for chronic laryngo-pharyngitis: a randomized placebo-control trial. Arch Otolarynol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El Serag HB, Lee P, Buchner A, Inadomi JM, Gavin M, McCarthy DM. Lansoprazole treatment of patients with chronic idiopathic laryngitis: a placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:979–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Stasney CR, et al. Treatment of chronic posterior laryngitis with esomeprazole. Laryngoscope. 2005 doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000192173.00498.ba. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swoger J, Ponsky J, Hicks DM, et al. Surgical fundoplication in laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) unresponsive to aggressive acid suppression: a prospective concurrent controlled study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.01.011. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swoger J, Ponsky J, Hicks DM, et al. Surgical fundoplication in laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) unresponsive to aggressive acid suppression: a prospective concurrent controlled study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.01.011. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.So JBY, Zeitels SM, Rattner DW. Outcomes of atypical symptoms attributed to gastroesophageal reflux treated by laparoscopic fundoplication. Surgery. 1998;124:28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Westcott CJ, Hopkins MB, Bach K, Postma GN, Belafsky PC, Koufman JA. Fundoplication for laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]