Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the feasibility and safety of vaginal anterior and posterior myomectomy (A surgical technique is described.).

Design

Longitudinal prospective study.

Setting

A gynecology department of a university teaching hospital.

Population

Women with surgical indication for myomectomy for pelvic pain, menorrhagia, symptoms of pressure, or subfertility caused by uterine myomas.

Methods

From December 1998 to April 2005, all women with uterine myomas selected for surgical treatment were enrolled in a prospective study and underwent vaginal myomectomy.

Main Outcome Measures

Feasibility of vaginal myomectomy, surgical data and morbidity, and relief of symptoms.

Results

From 1998 to 2004, 54 patients underwent vaginal myomectomy. There were no cases of laparotomic conversion and hysterectomy. The average operation time was 80 minutes (range, 30 to 170 min). Average blood loss was 80 mL (range, 20 to 350 mL). No complications occurred. The average postoperative stay was 2 days (range, 1 to 3 days). Symptoms resolved in all 54 patients (100%) at 6 months follow-up, and 6 patients had a pregnancy.

Conclusion

Vaginal myomectomy, in well-selected cases, is feasible and well tolerated. Thanks to the “morcellation” technique, vaginal myomectomy can be useful even in case of large, numerous, and intramural fibroids and allows optimal uterine wall reconstruction with minimal tissue trauma. The procedure is also low time-consuming.

Readers are encouraged to respond to George Lundberg, MD, Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eye only or for possible publication via email:glundberg@medscape.net

Introduction

Up to 50% of uterine fibroids cause symptoms severe enough to warrant therapy. The surgical therapy, depending on the type of myoma, may consist of myomectomy and hysterectomy (by abdominal, laparoscopic, or vaginal route), myolysis, or hysteroscopic resection. In recent years, gynecologists have become increasingly interested in minimally invasive surgery, which has led to a shift toward the laparoscopic approach for surgical therapy.[1] Notwithstanding its advantages (eg, minimal scarring, minimal surgical trauma, minimal adhesions, and minimal postoperative pain and postoperative stay), the laparoscopic approach is less cost-effective than the laparotomic route because of the prolonged operative time and costly instruments.[2] Furthermore, in cases of enlarged, numerous, and intramural fibroids, laparoscopy does not allow easy removal of the myoma; nor does it allow optimal suturing of the uterine wall, unless it is performed by a skilled laparoscopic surgeon.[3,4]

Recently, minilaparotomy has been proposed as an alternative to the laparoscopic approach for minimally invasive surgical treatment of benign gynecologic disease.[5] Severe obesity (body mass index [BMI] > 35) and the desire for pregnancy, however, may be regarded as possible contraindications to minilaparotomy. In the first case, the laparotomic incision may have to be extended; and in the second case, tissue trauma to the reproductive organs may be greater than that caused by the laparoscopic approach.[5]

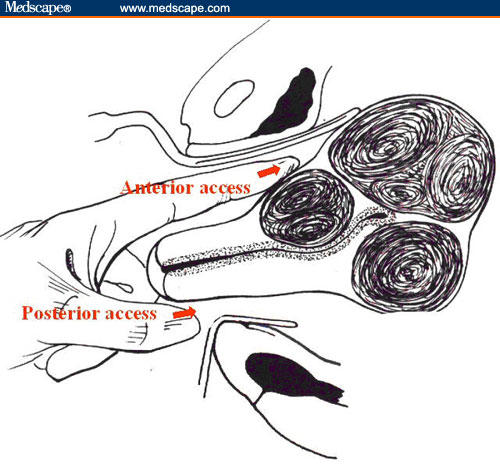

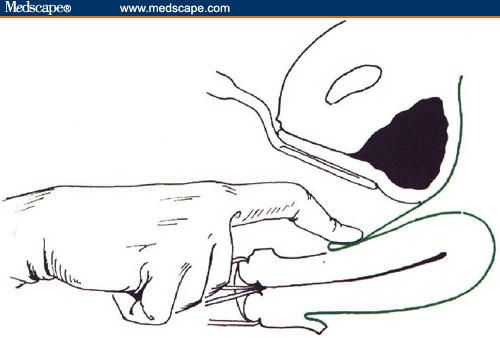

A third possible alternative route for the surgical treatment of benign uterine pathologies, is the vaginal approach (Figure 1). Davies and colleagues[6] first described the surgical technique of vaginal posterior myomectomy in a series of patients and reported no severe drawbacks. In 1998, Bessenay and colleagues[7] reported on 26 women who underwent vaginal myomectomy after culdotomy, which in some cases was laparoscopically assisted. In 1995, we had already described a cystectomy of dermoid ovarian cysts performed through a laparoscopic-assisted posterior culdotomy in a series of 18 patients, with no report of increased morbidity.[8] More recently, we performed a retrospective comparison of total laparoscopic (56 cases) and direct vaginal (30 cases) removal of ovarian dermoids, and we showed few but significant advantages of vaginal removal, particularly in relation to operating time and postoperative outcome.[9]

Figure 1.

The illustration shows the anterior and posterior access to the uterine wall.

Having achieved encouraging results in these studies, we designed a pilot study to evaluate the surgical safety and feasibility of vaginal myomectomy. In this study, we describe the surgical technique of vaginal myomectomy for posterior and anterior (Figures 1A and 1B) uterine fibroids, and we report on surgical data and morbidity in patients who underwent this treatment.

Methods

Since December 1998, as part of a prospective study at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the Civil Legnano Hospital, all patients with uterine myomatas who were selected for conservative surgical treatment (because of pain, infertility, bleeding) have undergone vaginal myomectomy.

Inclusion criteria are 1 myomas, diameter 9 cm according to ultrasound evaluation, and a well-mobilized uterus. Exclusion criteria are previous inflammatory disease, endometriosis, myomas > 9 cm, and previous pelvic operations. For anterior myomectomy, an additional exclusion criterion is bad vaginal compliance.

Transvaginal sonography to identify the number, size, and position of each myoma was essential to evaluate the feasibility of the vaginal surgical technique. An endometrial biopsy was routinely performed. Patients underwent appropriate bowel preparation. Ceftriaxone, 2 g intravenously, and methylergometrine, 0.2 mg intramuscularly, were administered to the patients at the induction of pre-anesthesia.

An important step in the procedure was the completion of a bimanual examination under anesthetic immediately before surgery. During surgery, it was useful to place the patient in a steep Trendelenburg position and to have retractor valves of varying lengths (5, 7, 10, 15, and 25 cm) and widths (2.2, 4 cm for each length < 9) in order to fit them according to vaginal size and compliance.

During the postoperative period, oral methylergometrine, 0.125-mg tablet, was administered (every 8 hours for 3 days) to all patients.

Criteria for hospital discharge included the following: absence of pain, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, fever, and pathologic vaginal bleeding; tolerance to oral feeding; spontaneous micturition; free passage of flatus; patient's desire for discharge; and absence of free fluid in the pelvis at ultrasound evaluation. All patients were evaluated 1 week after the operation.

The study was approved by the local institutional review board for clinical investigations and met all criteria put forth by the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent before participation in the study. A data safety and monitoring board provided data and safety oversight.

Posterior Myomectomy Surgical Technique

Figures 2 through 11 demonstrate the posterior myomectomy surgical technique.

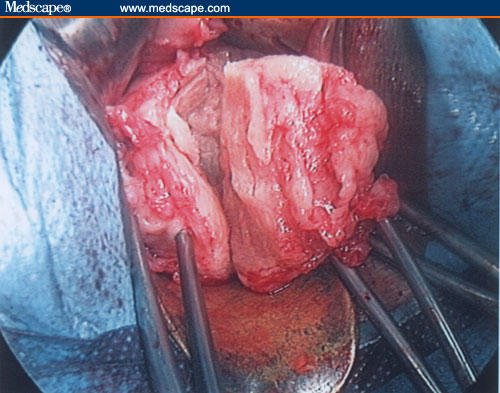

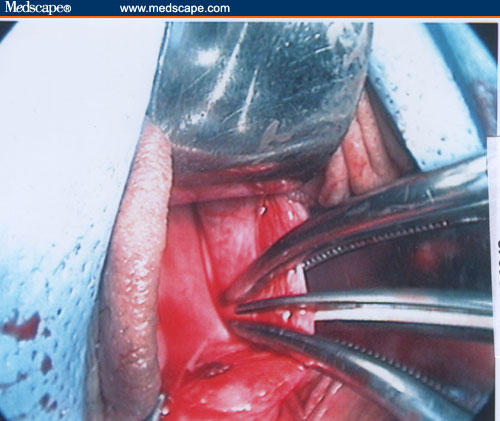

Figure 2.

Anterior (Fig. 2a), posterior (Fig. 2b), and lateral (Fig. 2c) retractors of adequate size for the patient are placed in the vagina.

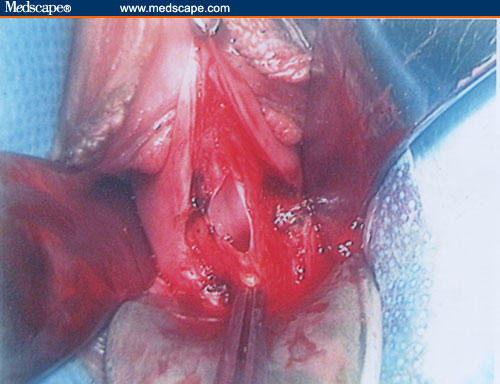

Figure 11.

Uterine wall reconstruction.

A digital intraoperative evaluation is performed to establish the position, number, and size of the fibroids and any adhesion.

If the myoma is in a lateral position, near the lateral uterine vessels, the surgeon must take care to perform the incision at a safe distance from them. The capsule of the myoma is dissected in order to obtain the enucleation of the myoma itself.

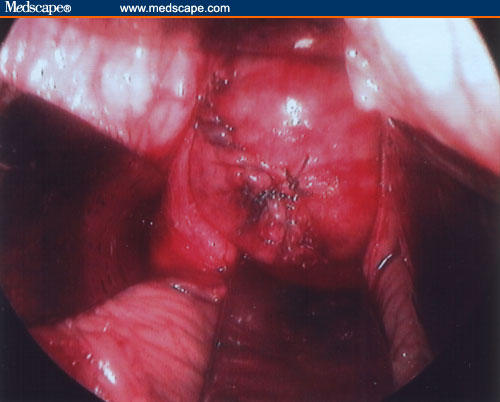

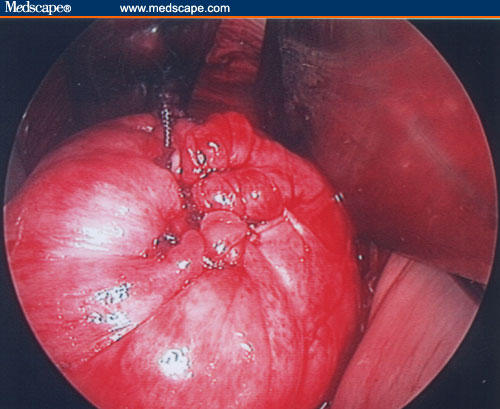

Both the uterine wall and serosa are reconstructed to avoid leaving dead space using a 00 or a 000 absorbable suture. In some cases, an antiadherent gel is applied to the uterine wall suture (Figures 9–11). The peritoneum is closed and, if necessary, a pelvic drain is used for 12 hours. The vaginal mucosa is sutured using a 0 rapidly absorbable continuing suture. A gauze with polyvinylpyrolidone is applied to the vagina for 12 hours.

Figure 9.

Uterine wall reconstruction.

Anterior Myomectomy Surgical Technique

The patient is catheterized and 100 mL of saline solution with methylene blue is introduced to identify any intraoperative bladder lesions.

Figures 12–21 demonstrate the anterior myomectomy surgical technique.

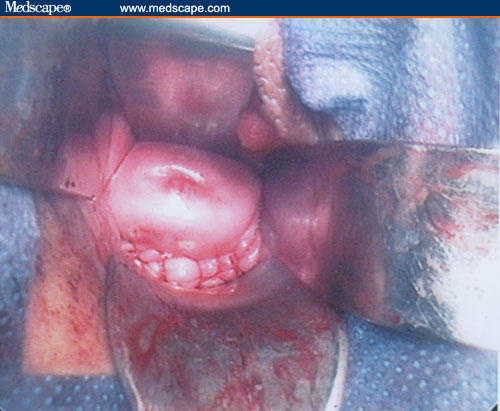

Figure 12.

A semicircular incision in the lateral right/anterior and lateral left fornix of about 4 to 5 cm is performed.

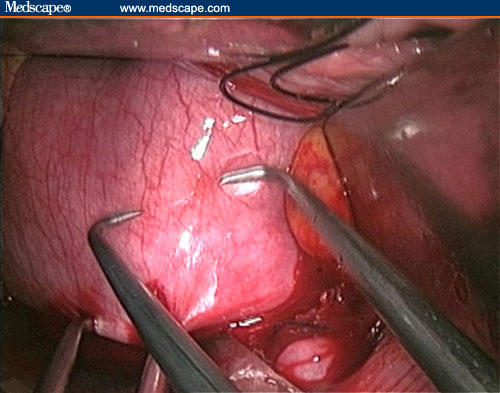

Figure 21.

Uterine wall reconstruction.

The procedure then continues in the same manner as for posterior myomectomy (Figures 19–22). After the peritoneum suture, the vesico-uterine ligaments are reconstructed using a 00 long absorbable suture. Colporrhaphy is performed using a 00 quick absorbable atraumatic suture, as previously described.

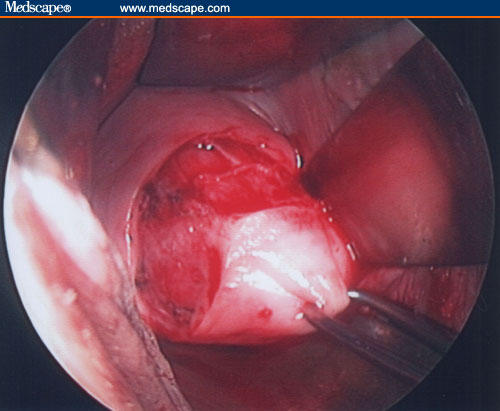

Figure 19.

Enucleation of the myoma.

Figure 22.

Uterine wall reconstruction.

Results

From December 1998 to April 2005, 54 patients were suitable candidates for vaginal myomectomy. For this group, the average age was 37 years (range, 29 to 46 years). The average BMI was 25 kg/m2 (range, 20 to 30 kg/m2).

The patients were treated as follows:

17 patients: anterior plus posterior multiple myomectomy

19 patients: posterior myomectomy

11 patients: anterior myomectomy

7 patients: multiple myomectomy (5 posterior; 2 anterior)

The mean operating time was 90 minutes. The average myoma size was 6 to 7 cm (range, 3.5 to 9.0 cm) in diameter, and the average blood loss was 80 mL (range, 20 to 350 mL). No case of laparotomic conversion occurred. Six hours after the intervention, only 20% of patients required mild analgesia (1 subcutaneous injection of morphine, 5 mg). No patients developed intraoperative or postoperative complications. The average postoperative stay was 2 days (range, 1 to 3 days). No cases of postoperative urinary tract sequelae were reported.

Discussion

In this study we demonstrate, for the first time, that the vaginal myomectomy is possible and feasible through anterior colpotomy. Milovanovic and colleagues [10] described the surgical technique for the vaginal posterior myomectomy in a series of patients, but in some cases these authors reported that they needed to remove anterior uterine fibroids.

The key points of the anterior vaginal myomectomy, in our opinion, are two. The first is the identification and the section of the anterior uterine bladder pillars after the anterior colpotomy in order to obtain more space for the operating field. The second is the use of specific retractor valves of various lengths and widths to fit them in accordance with vaginal size and compliance. For large fibroids, morcellation was a useful technique.

In this study, vaginal myomectomy was found to be a feasible and well-tolerated technique in well-selected patients. No case of laparotomic conversion was reported in our series. The average operative time (90 minutes), average blood loss (80 mL), and postoperative stay (average 2 days) and morbidity for the anterior approach myomectomy are comparable to those reported by other authors for similar types of operation (eg, a posterior wall approach). Bessenay and colleagues[7] reported an average operative time of 94 minutes, with a feasibility rate of 89%, with uncomplicated postoperative stay in most cases; in 3 cases, however, a laparotomic conversion was necessary. Davies and colleagues[6] reported an average operative time of 78 minutes, an average blood loss of 313 mL, and a feasibility rate of 91.4%. These authors also reported average postoperative stay of 3.9 days, 4 cases (11%) of postoperative pelvic hematoma, and a postoperative urinary tract infection rate of 11%. For their series of 31 women submitted to laparoscopically assisted vaginal myomectomy, Wang and colleagues[11] reported an average operative time of 79 minutes, average blood loss of 150 mL, average hospital stay of 3 days, and 2 cases (6.5%) of minor complications. In a prospective study of 359 patients who underwent laparoscopic myomectomy, Laudi and colleagues[12] reported an intraoperative complication rate of 3.3%, 2.7% transfusion rate, 3.3% pyrexia, and an average hospital stay of 2.8 ± 1.3 days. Finally, in a series of 128 patients submitted to laparotomic myomectomy, La Morte and colleagues[13] reported an average blood loss of 266 ± 45mL, 12% febrile morbidity, 1 case of conversion to hysterectomy, 1% deep venous thrombosis, and a wound infection rate of 1%.

One of the most common complications that occurs during myomectomy is excessive bleeding, and it is remarkable that we did not have cases that required blood transfusion. Davies and colleagues[6] reported an 11% transfusion rate (but 2 of 4 women transfused were anemic before surgery). We surmise that the intraoperative and postoperative administration of methylergometrine was useful to prevent this complication. Intramural injection of a vasoconstrictor is not useful during the operation, in our opinion, because it does not ensure that a complete hemostasis is realized with the reconstruction of the uterine wall.

Conclusion

This pilot study provides further evidence that, for myomectomy, the vaginal route is a useful alternative to the abdominal and laparoscopic approaches in well-selected patients. Vaginal myomectomy did not result in increased morbidity or postoperative stay in comparison to other laparoscopic and minilaparotomic approaches. Anterior and posterior myomectomy can be safely performed by the vaginal approach in well-selected patients, resulting in a good short-term success rate. Nevertheless, studies with larger numbers of patients are required to confirm our findings.

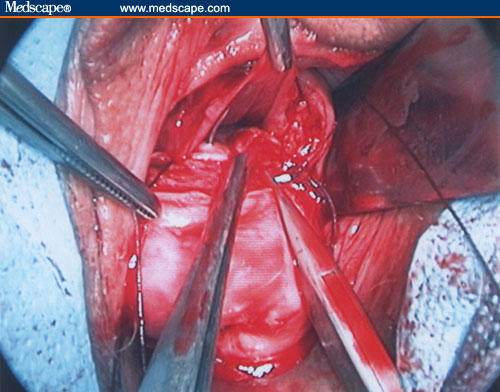

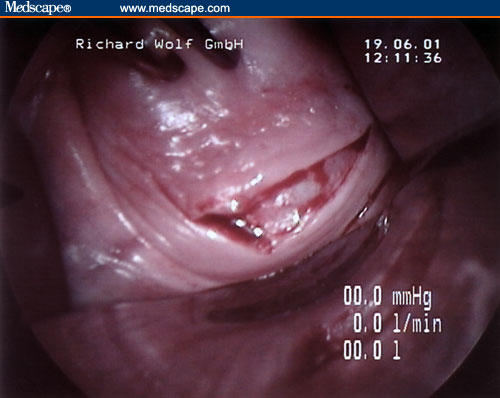

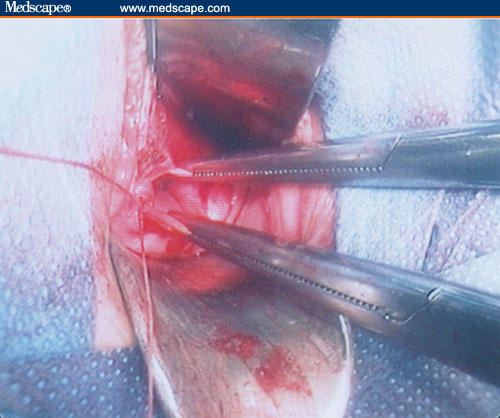

Figure 3.

The uterine cervix is clamped using Martin's forceps and rotated under the pubis bone to retroflex the uterus and to obtain the best exposure of the posterior fornix.

Figure 4.

A 4- to 5-cm incision in the posterior fornix is performed in the vaginal mucosa and fascia with a surgical scalpel to identify the peritoneum.

Figure 5.

The posterior peritoneum is opened up to increase the visibility of the surgical field, and a long narrow retractor at 45° inclination is placed in the Douglas pouch.

Figure 6.

A narrow anterior retractor is placed in the pelvis, on the posterior wall of the uterine cervix, in such a way as to ensure that the uterine cervix remains positioned under the pubis bone and to allow the best exposure of the posterior uterine wall.

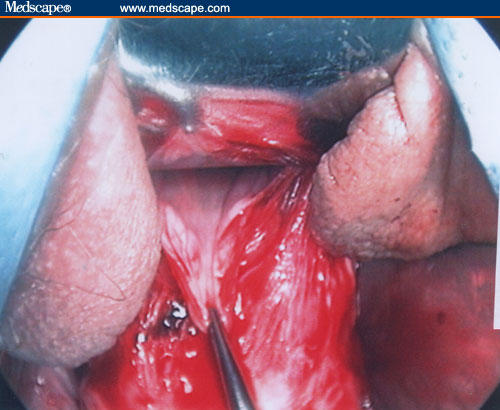

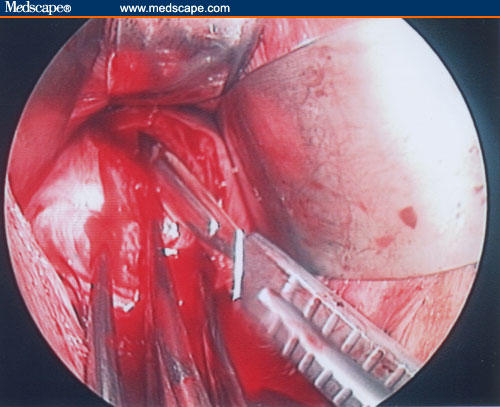

Figure 7.

The biggest of the myomas is grasped first using a Martin's clamp, and a longitudinal incision is performed on the uterine serosa until the myoma's capsule is observed.

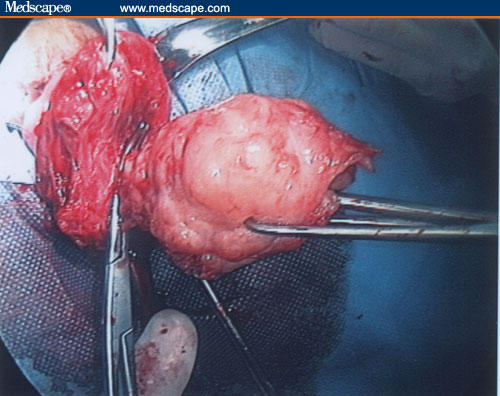

Figure 8.

In the case of large fibroid, it is possible to use the morcellation technique to reduce its volume progressively, extracting the tissue in cone shapes to avoid injury of the surrounding uterine vessels. Any remaining myomas are removed, successively.

Figure 10.

Uterine wall reconstruction.

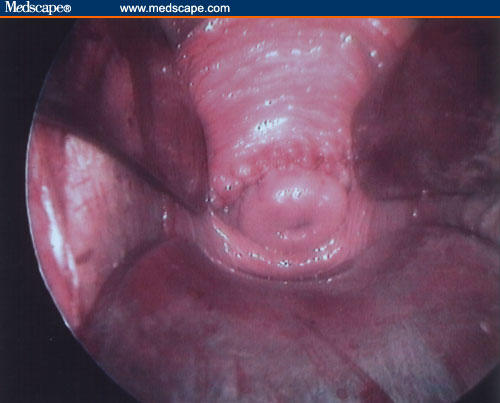

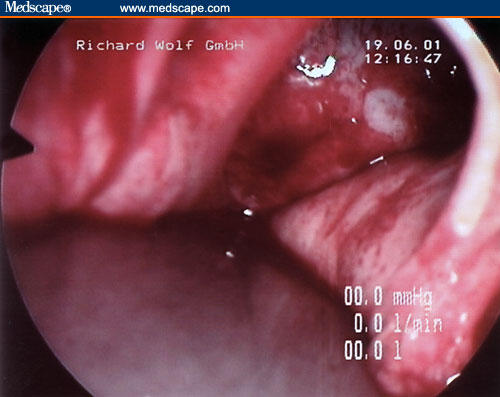

Figure 13.

Peritoneum identification.

Figure 14.

After peritoneum identification, the surgeon opens the anterior peritoneum using the scissors and introduces a retractor to push up the bladder, thus allowing exposure of the anterior bladder pillars. At this stage, a digital inspection is performed to check the uterine position.

Figure 15.

After placement of an anterior vaginal retractor to push up the bladder and a posterior retractor on the anterior wall of the cervix to push it down, it is possible to insert 2 retractors into the right and left fornix. At this point, the bladder pillars should be observed.

Figure 16.

After digitally identifying the ureters, the pillars are clamped and cut.

Figure 17.

A stitch is put in the stump of each ligament using a 0 long absorbable suture, so that they can be found and reconstructed easily at the end of the myomectomy.

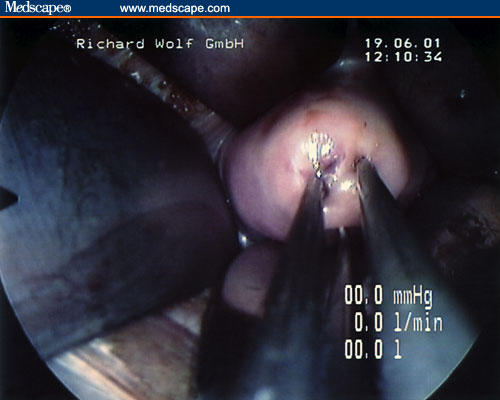

Figure 18.

The optimal dissection of the vesico-uterine space is required to correctly gain access to the anterior uterine wall.

Figure 20.

Uterine wall reconstruction.

Contributor Information

Roberto Carminati, Department of Obstetrics/Gynaecology, Legnano Civil Hospital, Legnano, Italy. Email: rcarm22@libero.it.

Antonio Ragusa, Department of Obstetrics/Gynaecology, Niguarda Civil Hospital, Milano, Italy.

Raffaella Giannice, Department of Obstetrics/Gynaecology, Legnano Civil Hospital, Legnano, Italy.

Francesco Pantano, Department of Obstetrics/Gynaecology, Legnano Civil Hospital, Legnano, Italy.

References

- 1.Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Operative laparoscopy (minimally invasive surgery): state of the art. J Gynecol Surg. 1992;8:111–141. doi: 10.1089/gyn.1992.8.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pittkin RM. Operative laparoscopy: surgical advance or technical gimmick? Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:441–442. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199203000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasson HM, Rotman C, Rana N, Sisos F, Dmowsky WP. Laparoscopie myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:884–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubuisson JB, Chapron C, Levy L. Difficulties and complications of laparoscopie myomectomy. J Gynecol Surg. 1996;12:159–165. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benedetti-Panici P, Maneschi F, Cutillo G, Scambia G, Congiu M, Mancuso S. Surgery by minilaparotomy in benign gynecologic disease. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:44–46. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00441-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies A, Hart R, Magos AL. The excision of uterine fibroids by vaginal myomectomy: a prospective study. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:961–964. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bessenay F, Cravello L, Roger V, Cohen D, Blanc B. Vaginal myomectomy. Contracept Fertil Sex. 1998;26:448–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pardi G, Carminati R, Ferrari MM, Ferrazzi E, Bulfoni G, Marcozzi S. Laparoscopically assisted vaginal removal of ovarian dermoid cysts. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:129–132. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00309-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrari MM, Mezzopane R, Bulfoni A, et al. Surgical treatment of ovarian dermoid cysts: a comparison between laparoscopie and vaginal removal. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003;109:88–91. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(02)00510-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milovanovic Z, Stanojevic D. Myomectomy via the vagina. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2004;132:18–21. doi: 10.2298/sarh0402018m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang CJ, Yen CF, Lee CL, Soong YK. Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal myomectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7:510–514. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laudi S, Zaccoletti R, Ferrari L, Minelli L. Laparoscopie myomectomy: technique, complications, and ultrasound scan evaluations. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8:231–240. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60583-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaMorte AI, Laiwani S, Diamond MP. Morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;6:897–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]