Abstract

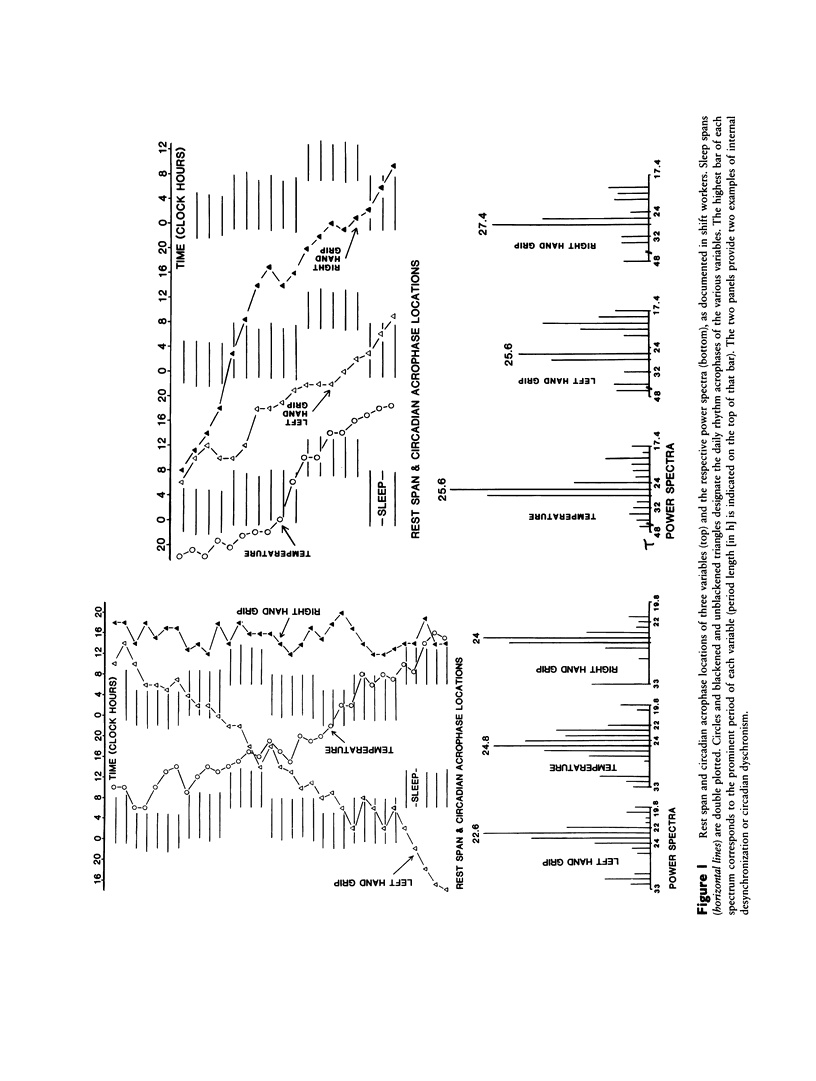

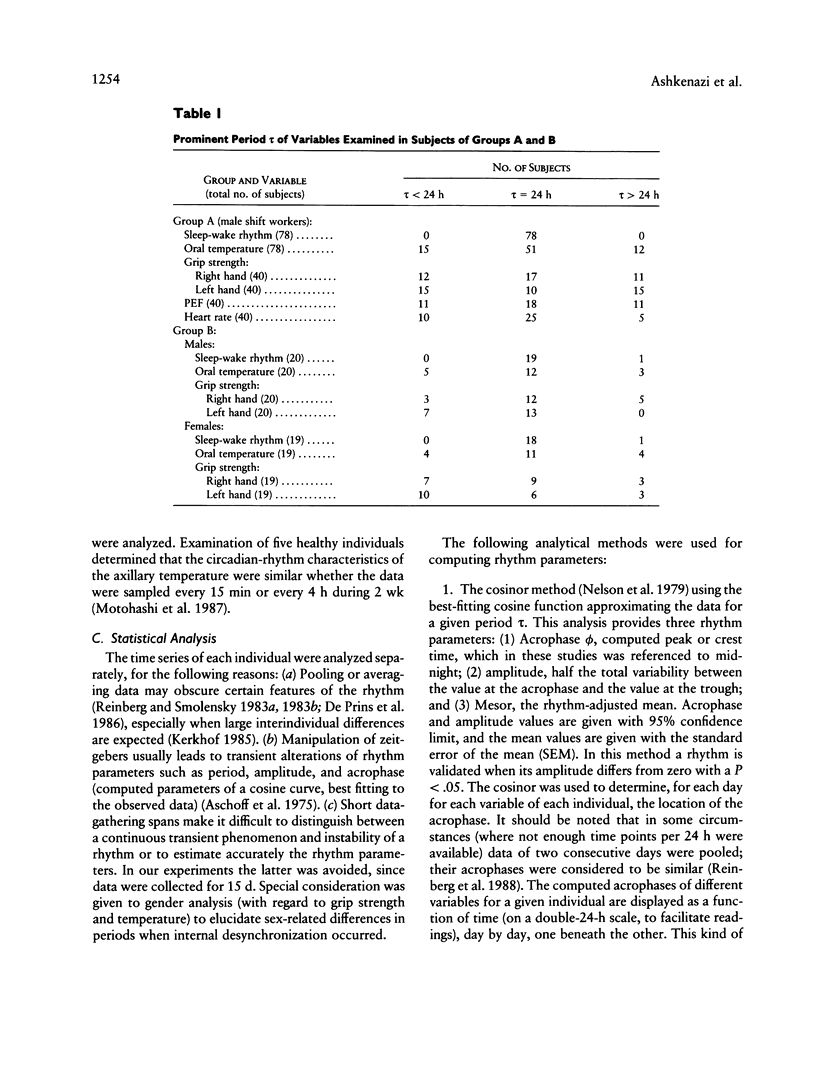

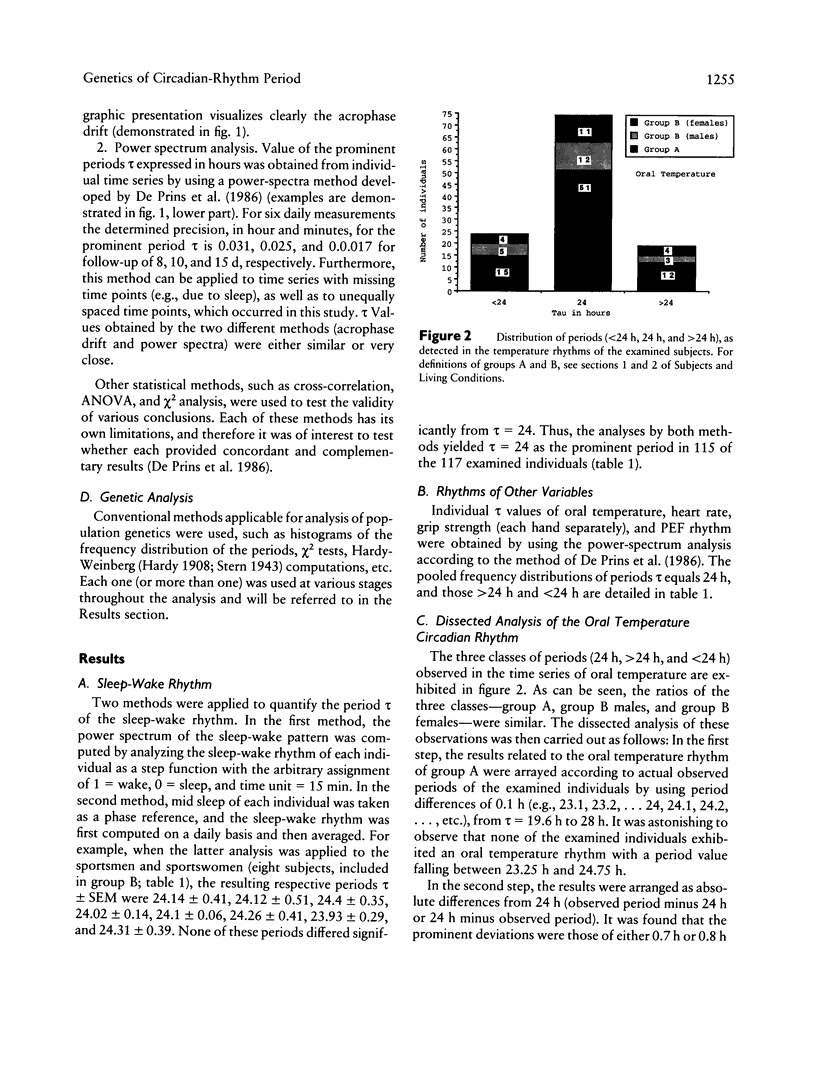

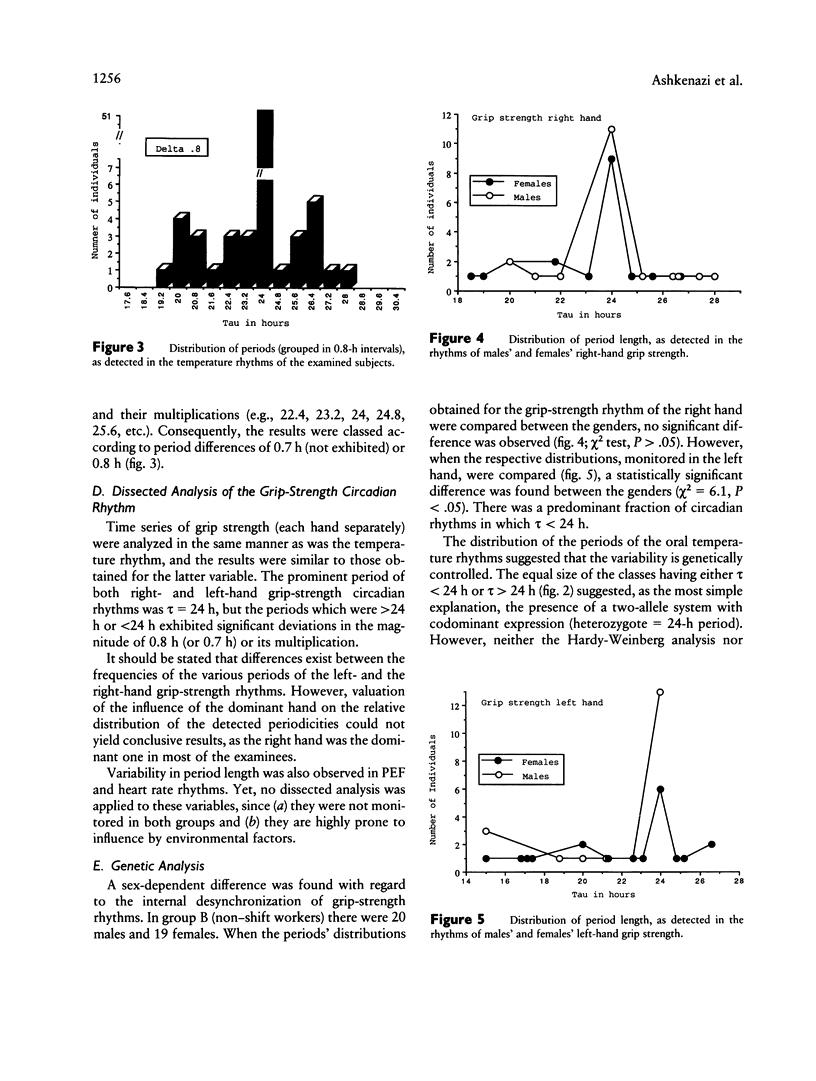

As a group phenomenon, human variables exhibit a rhythm with a period (tau) equal to 24 h. However, healthy human adults may differ from one another with regard to the persistence of the 24-h periods of a set of variables' rhythms within a given individual. Such an internal desynchronization (or individual circadian dyschronism) was documented during isolation experiments without time cues, both in the present study involving 78 male shift workers and in 20 males and 19 females living in a natural setting. Circadian rhythms of sleep-wake cycles, oral temperature, grip strength of both hands, and heart rate were recorded, and power-spectra analyses of individual time series of about 15 days were used to quantify the rhythm period of each variable. The period of the sleep-wake cycle seldom differed from 24 h, while rhythm periods of the other variables exhibited a trimodal distribution (tau = 24 h, tau > 24 h, tau < 24 h). Among the temperature rhythm periods which were either < 24 h or > 24 h, none was detected between 23.2 and 24 h or between 24 and 24.8 h. Furthermore, the deviations from the 24-h period were predominantly grouped in multiples of +/- 0.8 h. Similar results were obtained when the rhythm periods of hand grip strength were analyzed (for each hand separately). In addition, the distribution of grip strength rhythm periods of the left hand exhibited a gender-related difference. These results suggested the presence of genetically controlled variability. Consequently, the distribution pattern of the periods was analyzed to elucidate its compatibility with a genetic control consisting of either a two-allele system, a multiple-allele system, or a polygenic system. The analysis resulted in structuring a model which integrates the function of a constitutive (essential) gene which produces the exact 24-h period (the Dian domain) with a set of (inducible) polygenes, the alleles of which, contribute identical time entities to the period. The time entities which affected the rhythm periods of the variables examined were in the magnitude of +/- 0.8 h. Such an assembly of genes may create periods ranging from 20 to 28 h (the Circadian domain). The model was termed by us "The Dian-Circadian Model." This model can also be used to explain the beat phenomena in biological rhythms, the presence of 7-d and 30-d periods, and interindividual differences in sensitivity of rhythm characteristics (phase shifts, synchronization, etc.) to external (and environmental) factors.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Apfelbaum M., Reinberg A., Nillus P., Halberg F. Rythmes circadiens de l'alternance veille-sommeil pendant l'isolement souterrain de sept jeunes femmes. Presse Med. 1969 May 17;77(24):879–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschoff J., Fatranska M., Gerecke U., Giedke H. Twenty-four-hour rhythms of rectal temperature in humans: effects of sleep-interruptions and of test-sessions. Pflugers Arch. 1974;346(3):215–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00595708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschoff J., Hoffmann K., Pohl H., Wever R. Re-entrainment of circadian rhythms after phase-shifts of the Zeitgeber. Chronobiologia. 1975 Jan-Mar;2(1):23–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcal R., Sova J., Krizanovska M., Levy J., Matousek J. Genetic background of circadian rhythms. Nature. 1968 Dec 14;220(5172):1128–1131. doi: 10.1038/2201128a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargiello T. A., Young M. W. Molecular genetics of a biological clock in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Apr;81(7):2142–2146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberg F., Reinberg A. Rythmes circadiens et rythmes de basses fréquences en physiologie humaine. J Physiol (Paris) 1967;59(1 Suppl):117–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson B. R., Halberg F., Tuna N., Bouchard T. J., Jr, Lykken D. T., Cornelissen G., Heston L. L. Rhythmometry reveals heritability of circadian characteristics of heart rate of human twins reared apart. Cardiologia. 1984 May-Jun;29(5-6):267–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy G. H. MENDELIAN PROPORTIONS IN A MIXED POPULATION. Science. 1908 Jul 10;28(706):49–50. doi: 10.1126/science.28.706.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkhof G. A. Inter-individual differences in the human circadian system: a review. Biol Psychol. 1985 Mar;20(2):83–112. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(85)90019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopka R. J., Benzer S. Clock mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971 Sep;68(9):2112–2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.9.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motohashi Y., Reinberg A., Levi F., Nougier J., Benoit O., Foret J., Bourdeleau P. Axillary temperature: a circadian marker rhythm for shift workers. Ergonomics. 1987 Sep;30(9):1235–1247. doi: 10.1080/00140138708966019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson W., Tong Y. L., Lee J. K., Halberg F. Methods for cosinor-rhythmometry. Chronobiologia. 1979 Oct-Dec;6(4):305–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinberg A., Andlauer P., Bourdeleau P., Lévi F., Bicakova-Rocher A. Rythme circadien de la force des mains droites et gauches: désynchronisation chez certains travailleurs postés. C R Acad Sci III. 1984;299(15):633–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinberg A., Andlauer P., De Prins J., Malbecq W., Vieux N., Bourdeleau P. Desynchronization of the oral temperature circadian rhythm and intolerance to shift work. Nature. 1984 Mar 15;308(5956):272–274. doi: 10.1038/308272a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinberg A., Brossard T., Andre M. F., Joly D., Malaurie J., Lévi F., Nicolai A. Interindividual differences in a set of biological rhythms documented during the high arctic summer (79 degrees N) in three healthy subjects. Chronobiol Int. 1984;1(2):127–138. doi: 10.3109/07420528409059130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinberg A., Migraine C., Apfelbaum M., Brigant L., Ghata J., Vieux N., Laporte A., Nicolai Circadian and ultradian rhythms in the feeding behaviour and nutrient intakes of oil refinery operators with shift-work every 3--4 days. Diabete Metab. 1979 Mar;5(1):33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinberg A., Motohashi Y., Bourdeleau P., Andlauer P., Lévi F., Bicakova-Rocher A. Alteration of period and amplitude of circadian rhythms in shift workers. With special reference to temperature, right and left hand grip strength. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1988;57(1):15–25. doi: 10.1007/BF00691232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinberg A., Proux S., Bartal J. P., Lévi F., Bicakova-Rocher A. Circadian rhythms in competitive sabre fencers: internal desynchronization and performance. Chronobiol Int. 1985;2(3):195–201. doi: 10.1080/07420528509055559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinberg A., Touitou Y., Restoin A., Migraine C., Levi F., Montagner H. The genetic background of circadian and ultradian rhythm patterns of 17-hydroxycorticosteroids: a cross-twin study. J Endocrinol. 1985 May;105(2):247–253. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1050247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern C. THE HARDY-WEINBERG LAW. Science. 1943 Feb 5;97(2510):137–138. doi: 10.1126/science.97.2510.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]