Abstract

An unusual intramembranous cleavage of the β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) by γ-secretase is the final step in the generation of amyloid β-peptide (Aβ). Two conserved aspartates in transmembrane (TM) domains 6 and 7 of presenilin (PS) 1 are required for Aβ production by γ-secretase. Here we report that the APP C-terminal fragments, C83 and C99, which are the direct substrates of γ-secretase, can be coimmunoprecipitated with both PS1 and PS2. PS/C83 complexes were detected in cells expressing endogenous levels of PS. The complexes accumulate when γ-secretase is inactivated either pharmacologically or by mutating the PS aspartates. PS1/C83 and PS1/C99 complexes were detected in Golgi-rich and trans-Golgi network-rich vesicle fractions. In contrast, complexes of PS1 with APP holoprotein, which is not the immediate substrate of γ-secretase, occurred earlier in endoplasmic reticulum-rich vesicles. The major portion of intracellular Aβ at steady state was found in the same Golgi/trans-Golgi network-rich vesicles, and Aβ levels in these fractions were markedly reduced when either PS1 TM aspartate was mutated to alanine. Furthermore, de novo generation of Aβ in a cell-free microsomal reaction occurred specifically in these same vesicle fractions and was markedly inhibited by mutating either TM aspartate. Thus, PSs are complexed with the γ-secretase substrates C83 and C99 in the subcellular locations where Aβ is generated, indicating that PSs are directly involved in the pathogenically critical intramembranous proteolysis of APP.

Proteolytic cleavages of the integral membrane protein, β-amyloid precursor protein (APP), result in generation of the 40- and 42-residue amyloid β-peptides (Aβ) that accumulate to high levels in brain regions important for memory and cognition in Alzheimer's disease. APP is cleaved by β-secretase to generate a 99-residue C-terminal fragment (CTF) (C99) that then is cleaved by γ-secretase to generate Aβ40 and Aβ42. γ-Secretase has a critical role in determining the amount of Aβ produced by cells, but its identity is not definitively established.

Mutations in the presenilin (PS) 1 and 2 genes account for about 50% of early onset familial Alzheimer's disease cases. These mutations result in a selective increase in Aβ42 in the patients' brains, plasma, and skin fibroblast media, and in stable cell lines and transgenic mice overexpressing mutant PS1 or PS2 (reviewed in ref. 1). Conversely, deleting the PS1 gene in mice sharply inhibits both Aβ40 and Aβ42 production and elevates the APP substrates of γ-secretase, C83 and C99 (2–4). Moreover, mutation of either of two conserved aspartates within the sixth and seventh transmembrane (TM) domains of PS1 and PS2 abrogates the γ-secretase cleavage of C99 and C83, thereby decreasing Aβ40 and Aβ42 production (5–7).

PSs also are required for the apparent intramembranous cleavage of Notch receptors that releases their cytoplasmic signaling domains to the nucleus (8–11). The Notch and APP TM domains do not share extensive sequence similarity, but both cleavage events are equally inhibited by peptidomimetic inhibitors designed from the APP cleavage site, implicating related or identical γ-secretase-like proteases with little sequence specificity (8). Furthermore, the two TM aspartate residues in PS also are required for the intramembranous proteolysis of Notch (6, 12). As in the case of full-length (FL)-APP (13), Notch precursors form complexes with PS in the secretory pathway (14). However, neither FL-APP nor these Notch precursors are themselves the direct substrates of γ-secretase. γ-Secretase cleavage of Notch requires binding of extracellular ligand (e.g., Delta) and a cleavage within the proximal ectodomain before the γ-secretase-type cleavage can occur within the plasma membrane (15, 16). Recently we provided evidence that PS1 forms complexes in the plasma membrane of transfected cells with mNotch1ΔE (12), a Notch-derived fragment that undergoes γ-secretase processing at or near the cell surface (15). Thus, PS1 binds the Notch-derived γ-secretase substrate at or near its site of proteolytic processing. An essential prediction of the hypothesis that PSs participate directly in the γ-secretase cleavage of APP is that the γ-secretase substrates C83 and C99 should complex with the PSs in the subcellular compartments where this cleavage occurs.

Here, we directly address this critical unresolved issue. Using several PS antibodies, we show that C99 and C83 do coimmunoprecipitate with PS1 and PS2. Importantly, these complexes can be detected in cells expressing endogenous levels of PS. The biological significance of this interaction is supported by the localization of these complexes to those subcellular compartments [Golgi- and trans-Golgi network (TGN)-enriched vesicles] in which most Aβ is found at steady state. Moreover, we use a cell-free reaction to show that these same vesicles mediate de novo generation of Aβ, and that the two TM aspartates of PS1 are required both for normal steady-state levels of intracellular Aβ and for the new generation of Aβ. Taken together, our results demonstrate that PS1 and PS2 bind to the γ-secretase substrates, providing compelling evidence for a direct role for PSs in the final proteolytic cleavage of APP that generates Aβ.

Methods

Cell Lines and Tissue Culture.

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell lines overexpressing wild-type (WT) human APP together with either WT human PS1 (designated WT PS1 cells) (17), D257A PS1 (2–1 cells) (5), D385A PS1 (3–1 cells) (5), or D257A PS1 plus D366A PS2 (2A-2 cells) (7) were maintained in 200 μg/ml G418 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) plus 2.5 μg/ml puromycin (for line WT PS1), 250 μg/ml of Zeocin (Invitrogen) (for lines 2–1 and 3–1), or 250 μg/ml Zeocin plus 250 μg/ml Hygromycin B (for line 2A-2). We also examined an HEK293 cell line transfected with “Swedish” mutant K595N/M596L APP695 (cell line 293695SW) that was maintained in 200 μg/ml G418. For pharmacological inhibition of γ-secretase, 70% confluent WT PS1 cells were incubated with either 50 μM compound 11 (18) or DMSO vehicle alone for 8 hr before lysis.

Subcellular Fraction Preparation and in Vitro Aβ Generation.

The preparation of subcellular fractions from stably transfected CHO cells (five 15-cm dishes, ≈1 × 108 cells, except for WT PS1 or 293695SW cells, with 10 15-cm dishes, ≈2 × 108 cells) has been described (3). The fractionation uses discontinuous Iodixanol gradients, which are used because they effectively separate endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-rich from Golgi/TGN-rich vesicles in a way that preserves vesicle structure and function, allowing de novo Aβ generation upon incubation at 37°C. For determination of steady-state intracellular Aβ levels, each vesicle fraction was lysed in 1% NP-40 and subjected to Aβ ELISA. For determination of de novo Aβ generation in vitro, a stock solution of 1 M NaCitrate (pH 5.6) was added to each fraction to reach a final concentration of 50 mM. Individual gradient fractions then were divided into two aliquots. One aliquot was used for determination of basal Aβ levels by adding an equal volume of stop solution [2% NP-40, 2 mM EDTA, 2× protease inhibitor cocktail (3), and 1 M guanidine HCl] and storing at −80°C. The other aliquot was incubated at 37°C for 4 hr followed by addition of an equal volume of stop solution. Aβ levels then were determined in both aliquots by ELISA, and the newly generated Aβ levels were calculated by subtracting the Aβ level observed at −80°C from that obtained at 37°C.

Coimmunoprecipitation and Western Blotting.

Cells were lysed in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.5% BSA, 0.5% Triton X-100, and the protease inhibitor mixture. Cell lysates were precleared with protein A agarose for 4 hr, and supernatants were immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies plus protein A agarose that had been preincubated in the lysis buffer for 4 hr to reduce nonspecific absorption. Immunoprecipitation (IP) proceeded overnight, and the coimmunoprecipitates were washed and detected as described (13). Polyclonal antibody C7 (19) and mAb 13G8 (gift of P. Seubert and D. Schenk, Elan Pharmaceuticals) are directed against amino acids 732–751 at the C terminus of APP (APP751 numbering). Polyclonal antibodies X81, R22 (14), and 4627 were raised against residues 1–81, 270–404, and 457–467 of PS1, respectively (20). mAb 13A11 was raised against residues 294–309 of PS1 (gift of P. Seubert and D. Schenk) (20). Polyclonal antibody 2972 (gift of C. Haass, Ludwig-Maximilians University) and PS2L (gift of T. Iwatsubo, T. Saido, K. Maruyama, and T. Tomita, Tokyo University, Tokyo) were raised against residues 1–75 and 316–339 of PS2, respectively (21). Anticalnexin antibody was purchased from StressGen Biotechnologies, Victoria, Canada. Detection on Western blots used appropriate secondary antibodies and an enhanced chemiluminescence system.

Galactosyltransferase Activity Assay.

The β-1,4-galactosyltransferase assay as a marker for Golgi/TGN-type vesicles was performed on the Iodixanol fractions (above) according to the method of Bretz and Staubli (22), in which the addition of [3H]galactose onto the oligosaccharides of an acceptor protein, ovomucoid, is measured.

ELISA.

Aβ sandwich ELISAs were performed as described (23). The capture antibodies were 266 (to Aβ residues 13–28) for total Aβ and 2G3 (to Aβ residues 33–40) for AβX-40 species. The reporter antibodies were biotinylated 3D6 (to Aβ residues 1–5) for total Aβ and 266 for AβX-40 species. These antibodies were kindly provided by P. Seubert and D. Schenk.

Results

Detection of Complexes of PS1 with APP CTFs and the Accumulation of the Complexes After Inactivation of γ-Secretase.

We (13) and others (24, 25) have previously reported the formation of specific complexes of FL-APP and PS in several different cell types. We observed such complexes even at endogenous levels of both proteins without the need for overexpression (see figure 3E of ref. 13). In COS cells transiently transfected with cDNAs encoding PSs and an artificial APP CTF, C100, Pradier et al. (25) reported complexes of C100 with PS1 or PS2. Because overexpressed proteins tend to interact nonspecifically and form aggregates in transiently transfected cells, it is critical to examine the occurrence, localization, and physiological significance of complexes between PS1 and the natural CTFs derived from FL-APP without transient transfection of both PS1 and recombinant APP CTFs. Therefore, we searched extensively for the binding of PS to the natural APP CTFs C99 and C83 that are the direct substrates of γ-secretase, both in PS1-transfected stable cell lines and in cells expressing only endogenous PS1, by using a modified and sensitive coimmunoprecipitation method (see Methods).

We first characterized the expression levels of PS1 and PS2 in the stable CHO cell lines WT PS1, 3–1, and 2A-2. Both PS1 N-terminal antibody X81 and “loop” antibody R22 immunoprecipitated FL-PS1 (Fig. 1a). Using antibody R22, PS1 CTFs were readily precipitated from WT human PS1-expressing cells (WT PS1). Longer Western blot exposure of the X81-precipitated sample revealed only a trace amount of CTF brought down by the N-terminal antibody (data not shown). This latter result indicates that only a small portion of PS1 CTFs can be recovered as stable heterodimeric complexes with PS1 N-terminal fragments (NTFs) under the particular detergent conditions (1% NP-40 plus 0.5% Triton X-100) used here, which is consistent with two other studies that show a lack of NTF/CTF coimmunoprecipitation in the presence of 0.5% (26) or 1% (27) Triton X-100. The NTF/CTF complex has been observed only when 1% digitonin (26) or 2% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) (27) are used as detergents to solublize membranes. Our result thus demonstrates the relative stringency of the coimmunoprecipation conditions used here to detect protein–protein interactions. As reported previously (5), the PS1 D385A stable cell line 3–1 showed significantly reduced levels of the endogenous hamster PS1 CTF and none of the slightly larger human CTF (because PS1 D385A cannot undergo endoproteolysis) (Fig. 1a). Cell line 2–1 (PS1 D257A) showed a similar pattern, as expected (data not shown). Moreover, the double Asp-mutant stable line 2A-2 (PS1 D257A + PS2 D366A) had undetectable PS1 CTF levels (Fig. 1a), as reported (7). Neither human nor endogenous (hamster) PS2 fragments could be detected in line 2A-2, although a high level of FL mutant human PS2 was stably expressed, as detected by IP/Western blotting with PS2 antibody 2972 (Fig. 1b) (7).

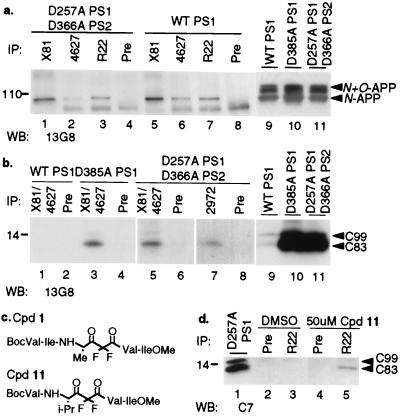

Figure 1.

Expression of PS1 and PS2 in WT and asp-mutant PS1/PS2 cells. (a) CHO cells stably expressing WT PS1, D385A PS1, or D257A PS1 plus D366A PS2 were lysed and immunoprecipitated (IP) with PS1 polyclonal antibodies X81 to the NTF, R22 to both NTF and CTF, or preimmune serum (pre) from rabbit X81. The precipitates were probed by Western blotting (WB) with PS1 mAb 13A11 to the CTF. (b) Lysates from untransfected cells or PS1/PS2 double asp-mutant cells were immunoprecipitated and Western blotted with PS2 antibody 2972.

We next sought to determine whether PS can complex with C99 and C83 derived naturally from FL-APP, and if so, whether there was any difference in complex formation between WT and asp-mutant isoforms of PS. Because all three cell lines (WT PS1, 3–1, and 2A-2) are derived from the same parental cell line that stably overexpress WT human APP, Western blotting of their cell lysates with the APP C-terminal antibody 13G8 showed closely similar levels of N- and N + O-glycosylated APP (Fig. 2a, lanes 9–11). As previously reported (5), C99 and C83 levels were markedly elevated in the asp-mutant cells (Fig. 2b, lanes 10 and 11 vs. lane 9).

Figure 2.

Accumulation of PS/APP-CTF complexes after inactivation of γ-secretase in stably transfected cells. (a) Lysates from PS WT (lanes 5–8) and asp-mutant (lanes 1–4) stable transfectants were coimmunoprecipitated (IP) with either PS1 antibodies (X81, 4627, or R22) or preimmune serum (pre), as indicated, followed by Western blotting (WB) with APP antibody 13G8. The APP species that coprecipitated with both WT and asp-mutant PS1 comigrated with the N-glycosylated form of APP detected on straight Western blots of the lysates (lanes 9–11). The lower band in lanes 2–4 and 6–8 is nonspecific. (b) Cell lysates were coimmunoprecipitated with PS1 antibodies (combined X81 and 4627, lanes 1, 3, and 5), PS2 antibody 2972 (lane 7), or preimmune serum (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). Precipitates were probed by Western blotting with APP antibody 13G8. The C83 and C99 that coprecipitate with PS1 and PS2 are only a small fraction of the C99 and C83 detected by straight Western blotting (WB) of 1/20th the amount of the respective cell lysates with 13G8 (lanes 9–11). (c) Structure of the difluoro ketone peptidomimetic γ-secretase inhibitors, compounds 1 and 11. (d) Lysates from WT PS1 cells treated with vehicle alone (DMSO) or the reported γ-secretase inhibitor Cpd 11 for 8 hr were coimmunoprecipitated with PS1 antibody R22 (lanes 3 and 5) or preimmune serum (lanes 2 and 4). Precipitates were probed by Western blotting (WB) with APP antibody C7 to detect C83. Small amounts of C99 (which is substantially less abundant than C83) also can be coprecipitated with PS1, but this is very difficult to visualize photographically. Lane 1 shows a straight C7 Western blot of a D257A PS1 cell lysate to indicate the gel positions of C83 and C99.

When cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with PS1 antibodies X81, 4627, or R22 followed by Western blotting with the APP C-terminal antibody 13G8, FL-APP was coimmunoprecipitated with both WT PS1 (Fig. 2a, lanes 5–7) and asp-mutant PS1 (Fig. 2a, lanes 1–3). Consistent with previous findings (13, 24), it was the N-glycosylated form of FL-APP that was principally coprecipitated with PS1 (Fig. 2a). A specific coimmunoprecipitation of C99 and C83 with PS1 was readily observed with our improved coimmunoprecitation protocol (see Methods) in cells expressing asp-mutant PS1 (Fig. 2b, lanes 3 and 5). The precipitated CTFs comigrated with the C99 and C83 in lysates from these same APP-expressing cells that were directly Western blotted with 13G8 (Fig. 2b, lanes 9–11). The complexes were specific, as no APP CTFs were precipitated when a preimmune serum was used (Fig. 2b, lanes 4 and 6). No C99 or C83 was detected in total lysates of WT PS1 cells coimmunoprecipitated by PS1 antibodies (Fig. 2b, lane 1). C83 also could be precipitated by PS2 antibody 2972 from the 2A-2 double asp-mutant cells (Fig. 2b, lane 7).

As an alternative to inactivating γ-secretase activity by mutating the TM aspartates of PS, we inhibited γ-secretase pharmacologically with a small difluoroketone transition-state analogue inhibitor, compound 11 (Fig. 2c) (28). This compound is expected to inhibit γ-secretase activity by binding to its active site. In contrast to the situation in cells treated with the DMSO vehicle alone (Fig. 2d, lane 3), C83 could be coimmunoprecipitated with WT PS1 in cells treated with 50 μM compound 11 (Fig. 2d, lane 5), a dose that markedly inhibits Aβ production without causing cytotoxicity (28). Similar results were observed with another peptidomimetic γ-secretase inhibitor, compound 1 (28) (data not shown), that is also modeled after the γ-secretase cleavage site (residues Aβ41–45) within APP (Fig. 2c). Thus PS1/C83 complexes were detected in whole-cell lysates when γ-secretase was inhibited, either by mutating the TM aspartates or by blocking the active site with a peptidomimetic inhibitor.

Enrichment of PS1/APP CTF Complexes in Golgi- and TGN-Type Vesicles.

To examine the subcellular localization of the PS/APP-CTF complexes, we coimmunoprecipitated C99 and C83 with PS1 from isolated vesicle fractions. Cells were homogenized, and membrane vesicles (microsomes) were subjected to discontinuous Iodixanol gradient fractionation (3). Consistent with the previous characterization of these gradients (3), we found that fractions 1–4 were enriched in calnexin-positive ER vesicles (Fig. 3a). The immature N-glycosylated form of APP was localized to these same fractions (data not shown), as reported (3). Fractions 4–8 were enriched in β-1,4-galactosyltransferase activity (Fig. 3b), which is indicative of Golgi- and TGN-enriched vesicles (22, 29). The mature, N + O-glycosylated APP also was specifically enriched in these fractions (not shown), as reported (3). Fraction 4 in these discontinuous gradients represents a mixed fraction positive for both ER- and Golgi/TGN-rich vesicles (3). To detect the presence of WT PS complexes with the APP CTFs in these isolated vesicles, large amounts of cells (≈2 × 108) overexpressing WT human PS1 were fractionated, and individual fractions were immunoprecipitated with the combined PS1 antibodies X81 + 4627 (Fig. 3c Right), or with preimmune serum (Fig. 3c Left). Consistent with our previous results (3), N-glycosylated FL-APP coimmunoprecipitated with PS1 (Fig. 3c Upper Right). Almost all such complexes of FL-APP and PS1 were found in the ER-rich vesicles (fractions 1–4). In contrast, complexes between C83 and PS1 were recovered from the Golgi- and TGN-rich vesicle fractions (Fig. 3c Lower Right, fractions 5–8); very little or no such complexes were detected in ER-enriched vesicles. A similar result was obtained when fractions were prepared from the asp-mutant PS1 cells (line 3–1) or the double asp-mutant PS1/PS2 cells (line 2A-2) and immunoprecipitated with PS1 or PS2 antibodies (Fig. 3d). Both C83 and C99 coprecipitated with PS1 or PS2 in fractions enriched in Golgi/TGN vesicles (Fig. 3d, fractions 4–8), whereas the majority of FL-APP coimmunoprecipitated with PS1 or PS2 in the ER-rich fractions (data not shown). More complexes were detected in the fractions derived from asp-mutant PS1 cells than in those from WT PS1 cells (Fig. 3 c vs. d).

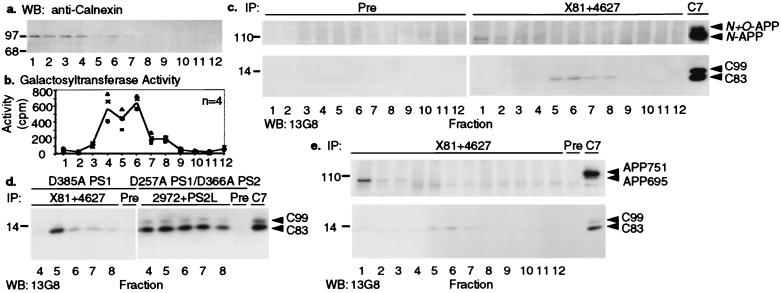

Figure 3.

Enrichment of PS/APP-CTF complexes in Golgi/TGN-rich subcellular fractions. (a) Distribution of the ER marker protein calnexin in discontinuous Iodixanol gradient fractions prepared from cells stably expressing WT PS1 was detected by Western blotting (WB) with anticalnexin antibody (densest fraction, lane 1; lightest fraction, lane 12). (b) Distribution of the Golgi/TGN marker β-1,4-galactosyltransferase activity was mainly in fractions 4–8 of WT PS1 cells. Curve represents the best fit for mean levels of four determinations (symbols). (c) Individual subcellular fractions (1–12) from cells expressing WT human PS1 were coimmunoprecipitated with PS1 antibodies X81 + 4627 (Right) or preimmune serum (Left), followed by Western blotting with APP antibody 13G8. FL N-APP that coimmunoprecipitated with PS1 is shown in the Upper Right (fractions 1–4); coprecipitating C83 is shown in the Lower Right (fractions 5–8). These coprecipitates comigrate, respectively, with the FL-APP and C83 species immunoprecipitated with APP antibody C7 (far right lane). (d) Individual subcellular fractions (only fractions 4–8 are shown) from the asp-mutant 3–1 cells (Left) or 2A-2 cells (Right) were coimmunoprecipitated with PS1 antibodies (X81 + 4627) or PS2 antibodies (2972 + PS2L), respectively. Fraction 6 was divided into two equal aliquots that were precipitated either with the indicated immune sera or with preimmune serum (Pre). APP antibody C7 was used to precipitate C83 and C99 as markers (far right lane). Precipitates were probed by Western blotting with APP antibody 13G8. (e) Individual subcellular fractions from human cells expressing endogenous levels of PS (cell line 293695SW) were coimmunoprecipitated with PS1 antibodies X81 + 4627 followed by Western blotting with 13G8. Fraction 6 was divided into two equal aliquots and precipitated with the immune sera or with a preimmune serum (Pre). FL human N-APP695 that coprecipitated with PS1 is shown (Upper) (fractions 1–3; the band below APP695 is nonspecific); the coprecipitating C83 is shown (Lower) (fractions 5–7).

To search for these complexes in another cell type, we examined a human 293 cell line stably expressing the “Swedish” (K595N/M596L) mutant APP695. Importantly, this cell line expresses only endogenous PSs. Consistent with the above results using human PS1-overexpressing cells, anti-PS1 but not preimmune serum brought down complexes of C83 with endogenous PS1 (Fig. 3e). Again, these complexes were principally detected in the Golgi/TGN-rich compartment (fractions 5–7), in contrast to FL-APP, which coimmunoprecipitated with endogenous PSs principally in the ER-rich compartment (fractions 1–3).

De Novo Aβ Generation in Golgi/TGN-Type Vesicles Containing PS/APP-CTF Complexes.

To examine whether PSs occur as complexes with C99 and C83 at the subcellular sites where Aβ actually is generated, we examined both steady-state Aβ levels and the capacity for new Aβ generation in subcellular fractions of WT and asp-mutant PS1 cells. Steady-state Aβ concentrations in each of the 12 Iodixanol gradient fractions prepared as before (Fig. 3) were measured by a sensitive and specific ELISA (Fig. 4a). In fractions from the WT PS1 cells, we detected Aβ peptides primarily in Golgi- and TGN-enriched vesicles (Fig. 4a, fractions 4–8, empty bars), consistent with our previous report (3). Vesicles isolated from cells expressing PS1 D257A (line 2–1) or PS1 D385A (line 3–1) showed markedly lower steady-state Aβ levels (Fig. 4a, filled bars). In the Golgi- and TGN-enriched fractions (fractions 4–8), intravesicular Aβ levels were decreased ≈60–70% from those in WT PS1 cells (P < 0.001 in both lines 2–1 and 3–1; n = 3–4). This result is in agreement with our previous finding that Aβ levels in the conditioned media of these same asp-mutant PS1 cells are about one-third those of WT PS1 cells (5). A similar result was obtained when a different ELISA with a capture antibody specific for the Aβ40 terminus (antibody 2G3) was used to measure AβX-40 levels (not shown). These results clearly demonstrate the effect of the TM aspartate mutations on the intracellular accumulation of Aβ and exclude the possibility that asp-mutant PS1 solely alters the secretion of Aβ into the medium.

Figure 4.

Steady-state Aβ levels and de novo Aβ generation in isolated subcellular fractions (a) WT and the indicated asp-mutant CHO cells were subjected to subcellular fractionation, and steady-state Aβ levels in each fraction were measured by sandwich ELISA (n = 3 or 4). (b) To measure de novo Aβ generation, each individual fraction was collected and incubated at either 37°C or −80°C (base line) for 4 hr. Levels of newly generated Aβ were established by subtracting the Aβ level at −80°C from that generated at 37°C (n = 8–10). Standard errors are indicated on each bar.

Next, new Aβ production was measured in these cell-free microsomes, in which the potential involvement of any protein trafficking effects of PS can be largely eliminated. We subjected the WT PS1, 2–1, or 3–1 cells to the same subcellular fractionation as before, yielding washed vesicles essentially devoid of cytosol. Individual fractions then were incubated at 37°C for 4 hr to allow de novo Aβ generation (or at −80°C to establish the basal Aβ levels). Substantial new production of Aβ was readily observed in fractions 4–8 from WT PS1 cells (Fig. 4b, empty bars). In contrast, vesicles prepared and incubated identically from asp-mutant cells showed only trace amounts of newly generated Aβ. The low levels of newly generated Aβ in fractions from the asp-mutant cells reflects residual γ-secretase activity, presumably mediated by residual endogenous PS1 and PS2 (5, 7) (see Discussion). Thus, in these cell lines stably expressing human APP and PS1, most Aβ is generated in the Golgi/TGN-rich compartments (Fig. 4b), precisely where C99 and C83 are found to physically interact with PS1 (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The discovery that the two TM aspartate residues in PS1 are required for γ-secretase activity, even in isolated microsomes (5), coupled with pharmacological evidence that γ-secretase is an aspartyl protease (28), suggested that PS1 itself might be the γ-secretase. A central prediction of this hypothesis is that PS physically contact these immediate substrates of γ-secretase in the subcellular compartments where they undergo proteolysis. The full subcellular localization of PS1 is not definitively determined. Although one study indicates that fragments of PS1 are not distributed beyond the cis-Golgi (30), other studies suggest that PS1 is located in the ER, ER-Golgi intermediate compartment, coated transport vesicles near Golgi stacks (31), and even at the cell surface, where PS1 has been shown to form complexes with all components of the adherens junctions (32). In addition, PSs have been shown to complex with Notch in the plasma membrane (12), where Notch becomes a substrate for γ-secretase after ligand-induced cleavage of the Notch ectodomain (33). Similar to these findings of a broad subcellular distribution of PS1, a series of studies indicates a variety of subcellular sites for Aβ generation. Some studies indicate a requirement for targeting APP to endosomes, where Aβ could be generated (34, 35). Intracellular Aβ also has been found in ER and Golgi compartments (3, 36–38). In the current study, we prepared subcellular fractions that are enriched in ER- or Golgi/TGN-type vesicles. These fractions also contain other vesicles. It was not our goal here to identify precisely which vesicle type contains PS1 and the subcellular locus for Aβ generation using the relatively crude density gradient method. Rather, we aimed to determine whether direct complexes between PS1 and APP CTF can be detected and whether these are localized to the same fractions where Aβ can be generated de novo. The majority of microsomes in the fractions containing both complexes and γ-secretase activity are Golgi/TGN-type vesicles, based on available markers (refs. 3 and 39 and this study).

Therefore, our results show that a subset of PS heterodimers, the population localized to Golgi- and TGN-type vesicles (39), is in the proper location and conformation to complex with C99/C83. We observed complex formation of WT PS1 with APP CTFs in the Golgi/TGN-rich compartments where new Aβ generation was detected. Asp-mutant PS1 enhanced the detection of complexes with C99/C83 but inhibited the γ-secretase activity in the same compartments. These observations demonstrate a close association of complex formation and Aβ generation, supporting a direct involvement of PS1 in the γ-secretase cleavage of APP.

Our results argue against the hypothesis that PS1 is involved in the γ-secretase mechanism indirectly by mediating the trafficking of APP and/or γ-secretase to certain subcellular compartments. In this study, membrane vesicles were fractionated and washed to ensure that cytosolic proteins were essentially removed and membrane trafficking would be minimal or absent between the fractionated vesicles. When we incubated each of the 12 gradient fractions individually at 37°C, we found that Aβ levels rose in Golgi/TGN-rich fractions from WT cells, not from asp-mutant cells. Under these strictly defined in vitro conditions, WT PS1 (but not asp-mutant PS1) must be directly involved in Aβ generation in the Golgi- and TGN-enriched fractions, independent of any membrane trafficking effects. The small amounts of newly generated Aβ detected in fractions 4–8 from the asp-mutant cells (Fig. 4b) most likely reflects the residual γ-secretase activity associated with residual endogenous PS1 and PS2 molecules. It recently has been shown that mutating either of the PS2 TM aspartates D263 or D366 also results in accumulation of C99/C83 and reduced Aβ generation (6, 7). Our coprecipitation of PS2 with C99 in transfected cells strongly suggests that PS1 and PS2 behave similarly in the process of Aβ generation and function directly in the γ-secretase cleavage of the APP CTFs by forming complexes with these substrates.

Our gradient fractionation results suggest that the initial binding between the APP and PS holoproteins occurs very early in the biosynthetic pathway, i.e., in the ER. Complex formation between PS and FL-APP is relatively stable and can be detected by coimmunoprecipitation because FL-APP is not itself a substrate for γ-secretase. Apparently only after the α- or β-secretase cleavages of FL-APP and the endoproteolysis of PS occur can the APP products C83 and C99 gain full and proper access to the active site of γ-secretase. Because the recently identified β-secretase shows highest activity in various compartments of the secretory pathway, including Golgi, TGN, and secretory vesicles (40), these α- or β-proteolytic processing events may occur whereas the FL-APP/PS complex traffics from ER through Golgi/TGN compartments. In the latter, complexes between C83/C99 and PS heterodimers [which are known to form in late ER and early Golgi (39)] would be expected to be transient because of rapid turnover of C83 and C99 to p3 and Aβ by γ-secretase, but blocking the function of the TM aspartates of PS1 by mutation appears to stabilize the complexes (Figs. 2b and 3d). If PS1 is the γ-secretase, C83/C99 may bind to PS1 at site(s) in addition to the active site (i.e., the TM aspartates). Thus, C83/C99 could, and apparently does, remain attached to PS1 when interactions between the active site and C83/C99 are disrupted by transition-state γ-secretase inhibitors (Fig. 2d). Importantly, the complexes could be detected in Golgi/TGN-rich compartments of cells expressing endogenous levels of PSs (Fig. 3e), demonstrating the physiological significance of such complexes in intravesicular Aβ production. In conclusion, our results provide clear evidence that PS1 is an integral part of the γ-secretase catalytic complex, with attendant implications for the intramembranous processing of several important substrates, including APP, Notch, and Ire1 (41). Additional study should help determine whether PS1 has intrinsic proteolytic activity or rather acts as an unprecedented and essential nonenzymatic diaspartyl cofactor in this unusual reaction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AG15379 and AG06173 to D.J.S.; AG17050 to A.M.G.), the Alzheimer's Association (W.X.), the American Health Assistance Foundation (A.M.G.), and the Richard Saltonstall Charitable Foundation (D.J.S.). W.J.R. is supported by a McDonnell Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Abbreviations

- Aβ

amyloid β-peptide

- PS

presenilin

- APP

β-amyloid precursor protein

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FL

full-length

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- NTF

N-terminal fragment

- CTF

C-terminal fragment

- TM

transmembrane

- WT

wild type

- TGN

trans-Golgi network

References

- 1.Selkoe D J. Nature (London) 1999;399:A23–A31. doi: 10.1038/399a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Strooper B, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Vanderstichele H, Gundula G, Annaert W, Von Figura K, Van Leuven F. Nature (London) 1998;391:387–390. doi: 10.1038/34910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xia W, Zhang J, Ostaszewski B, Kimberly W, Seubert P, Koo E, Selkoe D. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16465–16471. doi: 10.1021/bi9816195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naruse S, Thinakaran G, Luo J, Kusiak J W, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T, Qian X, Ginty D D, Price D L, Borchelt D R, et al. Neuron. 1998;21:1213–1221. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80637-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolfe M S, Xia W, Ostaszewski B L, Diehl T S, Kimberly W T, Selkoe D J. Nature (London) 1999;398:513–517. doi: 10.1038/19077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steiner H, Duff K, Capell A, Romig H, Grim M, Lincoln S, Hardy J, Yu X, Picciano M, Fechteler K, et al. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28669–28673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimberly W, Xia W, Rahmati T, Wolfe M, Selkoe D. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3173–3178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Strooper B, Annaert W, Cupers P, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Mumm J S, Schroeter E H, Schrijvers V, Wolfe M S, Ray W J, et al. Nature (London) 1999;398:518–522. doi: 10.1038/19083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Struhl G, Greenwald I. Nature (London) 1999;398:522–525. doi: 10.1038/19091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye Y, Lukinova N, Fortini M E. Nature (London) 1999;398:525–529. doi: 10.1038/19096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song W, Nadeau P, Yuan M, Yang X, Shen J, Yankner B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6959–6963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ray W J, Yao M, Mumm J, Schroeter E, Saftig P, Wolfe M, Selkoe D, Kopan R, Goate A M. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36801–36807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xia W, Zhang J, Perez R, Koo E H, Selkoe D J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8208–8213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ray W J, Yao M, Nowotny P, Mumm J, Zhang W, Wu J, Kopan R, Goate A M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3263–3268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kopan R, Schroeter E, Weintraub H, Nye J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1683–1688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroeter E H, Kisslinger J A, Kopan R. Nature (London) 1998;393:382–386. doi: 10.1038/30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia W, Zhang J, Kholodenko D, Citron M, Podlisny M B, Teplow D B, Haass C, Seubert P, Koo E H, Selkoe D J. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7977–7982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolfe M S, Citron M, Diehl T S, Xia W, Donkor I O, Selkoe D J. J Med Chem. 1998;41:6–9. doi: 10.1021/jm970621b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Podlisny M B, Tolan D, Selkoe D J. Am J Pathol. 1991;138:1423–1435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Podlisny M B, Citron M, Amarante P, Sherrington R, Xia W, Zhang J, Diehl T, Levesque G, Fraser P, Haass C, et al. Neurobiol Dis. 1997;3:325–337. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1997.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomita T, Maruyama K, Saido T C, Kume H, Shinozaki K, Tokuhiro S, Capell A, Walter J, Grunberg J, Haass C, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2025–2030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bretz R, Staubli W. Eur J Biochem. 1977;77:181–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson-Wood K, Lee M, Motter R, Hu K, Gordon G, Barbour R, Khan K, Gordon M, Tan H, Games D, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1550–1555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weidemann A, Paliga K, Durrwang U, Czech C, Evin G, Masters C L, Beyreuther K. Nat Med. 1997;3:328–332. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pradier L, Carpentier N, Delalonde L, Clavel N, Bock M, Buee L, Mercken L, Tocque B, Czech C. Neurobiol Dis. 1999;6:43–55. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu G, Chen F, Levesque G, Nishimura M, Zhang D M, Levesque L, Rogaeva E, Xu D, Liang Y, Duthie M, et al. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16470–16475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Capell A, Grunberg J, Pesold B, Diehlmann A, Citron M, Nixon R, Beyreuther K, Selkoe D J, Haass C. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3205–3211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfe M W, Xia W, Moore C, Leatherwood D, Ostaszewski B, Rahmati T, Donkor I, Selkoe D J. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4720–4727. doi: 10.1021/bi982562p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nilsson T, Pypaert M, Hoe M, Slusarewicz P, Berger E, Warren G. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:5–13. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Annaert W, Levesque L, Craessaerts K, Dierinck I, Snellings G, Westaway D, St. George-Hyslop P, Cordell B, Fraser P, De Strooper B. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:277–294. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lah J, Heilman C J, Nash N R, Rees H D, Yi H, Counts S E, Levey A I. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1971–1980. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-06-01971.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Georgakopoulos A, Marambaud P, Efthimiopoulos S, Shioi J, Cui W, Li H, Schutte M, Gordon R, Holstein G, Martinelli G, et al. Mol Cell. 1999;4:893–902. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80219-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mumm J, Schroeter E H, Saxena M, Griesemer A, Tian X, Pan D J, Ray W J, Kopan R. Mol Cell. 2000;5:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80416-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koo E, Squazzo S, Selkoe D J, Koo C H. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:991–998. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.5.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perez R, Soriano S, Hayes J, Ostaszewski B, Xia W, Selkoe D, Chen X, Stokin G, Koo E. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18851–18856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.18851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartmann T, Bieger S, Bruhl B, Tienari P, Ida N, Allsop D, Roberts G, Masters C, Dotti C, Unsicker K, Beyreuther K. Nat Med. 1997;3:1016–1020. doi: 10.1038/nm0997-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cook D, Forman M, Sung J, Leight S, Kolson D, Iwatsubo T, Lee V, Doms R. Nat Med. 1997;3:1021–1023. doi: 10.1038/nm0997-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilde-Bode C, Yamazaki T, Capell A, Leimer U, Steiner H, Ihara Y, Haass C. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16085–16088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J, Kang D E, Xia W, Okochi M, Mori H, Selkoe D J, Koo E H. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12436–12442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vassar R, Bennett B, Babu-Khan S, Kahn S, Mendiaz E, Denis P, Teplow D, Ross S, Amarante P, Loeloff R, et al. Science. 1999;286:735–741. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niwa M, Sidrauski C, Kaufman R, Walter P. Cell. 1999;99:691–702. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81667-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]