Abstract

Gene-for-gene disease resistance typically includes a programmed cell death response known as the hypersensitive response (HR). The Arabidopsis thaliana dnd1 mutant was previously isolated as a line that failed to produce the HR in response to avirulent Pseudomonas syringae pathogens; plants homozygous for the recessive dnd1-1 mutation still carry out effective gene-for-gene resistance. The dnd1-1 mutation also causes constitutive systemic resistance and elevated levels of salicylic acid. In the present study, a positional cloning approach was used to isolate DND1. DND1 encodes the same protein as AtCNGC2, a cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel of previously unknown organismal function that can allow passage of Ca2+, K+ and other cations [Leng, Q., Mercier, R. W., Yao, W. & Berkowitz, G. A. (1999) Plant Physiol. 121, 753–761]. By using a nahG transgene, we found that salicylic acid is required for the elevated resistance caused by the dnd1 mutation but that removal of salicylic acid did not completely eliminate the dwarf and loss-of-HR phenotypes of mutant dnd1 plants. A stop codon that would severely truncate the DND1 gene product was identified in the dnd1-1 allele. This demonstrates that broad-spectrum disease resistance and inhibition of the HR can be activated in plants by disruption of a cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel.

Gene-for-gene disease resistance in plants is characterized by specific recognition of certain pathogens and is controlled by plant resistance genes and pathogen avirulence genes with corresponding specificity (1, 2). The ensuing highly effective defense response typically includes the hypersensitive response (HR), a programmed cell death process in host cells immediately adjacent to the pathogen (3, 4). The HR apparently contributes to disease resistance by fostering release of antimicrobial enzymes and metabolites, by physically isolating the pathogen within defined lesions, and/or by enhancing local and systemic signaling to activate defenses in non-infected cells. However, cell death itself is not essential to limit pathogen growth. Many types of disease resistance do not involve HR cell death, and, even within gene-for-gene resistance, examples have emerged in which cell death is not essential (ref. 5 and references therein). For example, strong alleles of the Rx gene in potato condition resistance to Potato Virus X without activation of the HR (6, 7) whereas mutant ndr1 plants exhibit an HR-like response to some avirulent Pseudomonas syringae yet are disease-susceptible (8).

Systemic acquired resistance is a broad-spectrum form of disease resistance in which prior infection or immunizing treatment causes systemic activation of some defense responses and potentiation of subsequent responsiveness to pathogens (9–11). Systemic acquired resistance can confer varying levels of resistance against many different (but not all) viral, bacterial, and fungal plant pathogens. Salicylic acid and the NPR1 (NIM1) gene product are key mediators of systemic acquired resistance as well as gene-for-gene disease resistance. Additional defense activation pathways exist that are independent of salicylic acid (9, 10).

The dnd (defense, no death) class of mutants, including dnd1, dnd2, and Y15, were identified by their reduced ability to produce the HR in response to avirulent Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea (Psg) and were isolated in a screen designed to discover additional components of the avrRpt2-RPS2 disease resistance pathway in Arabidopsis (5, 12). The dnd1 mutant provides an example of gene-for-gene resistance without the HR. Despite the virtual absence of HR cell death, dnd1 mutants retain defense responses characteristic of gene-for-gene resistance such as strong induction of pathogenesis-related gene expression and the ability to severely limit pathogen growth (5). Interestingly, dnd1 plants also exhibit quantitative systemic acquired resistance-like resistance to a variety of virulent bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens, and are dwarfed in stature. This broad-spectrum resistance and dwarfing was likely to be attributable in part to the constitutive elevation of salicylic acid compounds observed in dnd1 plants, as similar phenomena have been observed in other Arabidopsis elevated-salicylate mutants (13). However, the loss-of-HR phenotype of dnd1 plants is unusual among characterized Arabidopsis mutants that display elevated salicylic acid levels (13, 14).

Some of the earliest detectable signaling events in plant defense responses include transmembrane ion fluxes (influx of Ca2+ and H+ and efflux of K+ and Cl−) and the production of reactive oxygen species such as superoxide and hydrogen peroxide (15–17). For example, physiological changes in membrane permeability are observed in parsley suspension cells between 2 and 5 min after treatment with a fungal elicitor (18). Resistant cowpea plants display an elevated level of cytosolic Ca2+ in infected epidermal cells whereas susceptible plants do not (19). Ca2+ channel blockers have been shown to inhibit HR in tobacco and soybean systems (20–23). Ca2+ channel blockers also disrupt other defense responses to fungal and bacterial elicitors (21, 24, 25). Ion fluxes are thought to be required for the activation of a mitogen-activated protein kinase, specific to defense responses, that may serve to activate gene expression after its translocation to the nucleus (26). Significantly, Ca2+ influx and the transient increase in cytosolic Ca2+ levels after elicitor treatment have been shown to be necessary and sufficient for the induction of the oxidative burst (27). Although these and numerous other studies have implicated ion fluxes in plant defense signaling (16, 28, 29), genetically based systems implicating ion channels in defense activation have not been available.

In the present study, we report the cloning and initial characterization of Arabidopsis DND1, which was found to encode a cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel. We also report evidence suggesting that salicylic acid is required for the elevated disease resistance but not the suppression of HR in dnd1 mutants.

Materials and Methods

High-Resolution Genetic Mapping.

Previously described restriction fragment length polymorphism markers (www.arabidopsis.org/) or bacterial artificial chromosome-derived cosmids (see below) were used to probe survey filters carrying restriction enzyme digests of Col-0 and No-0 genomic DNA. DNA of individuals from a Col-0 dnd1-1/dnd1-1 × No-0 F2 population that were known to carry recombination events between CHS1 and nga106 was digested, blotted, and probed to determine genotypes at these marker loci. The DND1 genotype of these individuals was determined by plant size and by HR testing, as described (5). Standard recombinant DNA methods (30) were used in these and all other experiments unless specifically noted.

BAC Identification and Alignment.

To identify BAC clones spanning the region of interest, a filter carrying the TAMU (Texas A&M University) Arabidopsis BAC library (Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center, Columbus, OH) was probed with markers pCIT1243 and nga106. pCIT1243 hybridized to TAMU BAC clone 21I05 and the Washington University BAC fingerprinting database indicated close similarity between 21I05 and IGF clone 1L1 (31). Similarly, nga106 identified IGF clone 5E1. These data oriented with respect to the genome a previously non-anchored contig from the IGF BAC contig database that contained 1L1 and 5E1 (32). The four BACs 8M21, 3H2, 22L1, and 23B17 were then selected from the IGF contig database as representatives of the relevant genomic region and were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center.

Creation and Mapping of Binary Cosmid Library.

To create a library competent for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation and spanning the putative DND1 locus, DNA of BACs 8M21, 3H2, 22L1, and 23B17 was isolated, was further purified by cesium chloride gradient, was partially digested with Sau3A to produce a predominance of 15- to 25-kb DNA fragments, was dephosphorylated with shrimp alkaline phosphatase, and then was ligated into the BamHI site of cesium chloride-purified binary/cosmid vector pCLD04541 (33). Ligation products were packaged as phage and were transfected into Escherichia coli XL1-Blue-MR by using the Gigapack III XL kit (Stratagene). Colonies were selected and purified on LB medium with tetracycline (10 μg/ml) and were stored at −60°C in 96-well microtiter plates. To determine overlap between cosmids and to allow for rough mapping with respect to the source BAC clones, cosmids were fingerprinted with restriction enzymes unique to the vector polylinker, and unique cosmids were double-digested with EcoRI and XbaI and blotted to nylon membrane along with single-enzyme digested BAC DNA. Blots were probed with select cosmids that were 32P-labeled. pBeLoBAC (BAC vector) DNA was used to probe cosmid blots to identify cosmid subclones that contained vector DNA.

Functional Complementation of the dnd1 Phenotype.

Cosmid clones spanning BACs 8M21, 3H2, 22L1, and 23B17 were moved into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101(MP90) (34) by electroporation or by tri-parental mating, and were used to transform Arabidopsis dnd1/dnd1mutants via the floral dip method (35). After selection for 7–10 days on kanamycin media, primary transformants were transplanted to soil and were grown for an additional ≈4 weeks, at which time the rosette sizes of individual transformants were compared with those of kanamycin-resistant Col-0 controls that were similarly selected on kanamycin plates and transplanted to soil. T2 seeds for subsequent analysis were collected after self-fertilization of these primary (T1) transformants.

Bacterial Growth and HR Experiments.

Growth of bacterial populations within leaves was determined by vacuum infiltration of 5 × 104 colony-forming units/ml P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (Pst DC3000) carrying either avrRpt2 (pV288) or no avr gene (pVSP61, vector only), leaf sampling, and plating on selective media, as described (5). Ability to produce the HR was tested as described (5) by hand inoculation of three leaves on each plant using an OD600 = 0.2 suspension (≈2 × 108 colony-forming units/ml) of P. syringae pv. glycinea Race 4 (Psg R4) carrying avrRpt2; an additional leaf was inoculated with Psg R4 (pVSP61) as a control. The severity of HR was rated on a 0–5 scale (0 = no visible tissue collapse; 5 = total collapse of infiltrated area).

Subcloning, Complementation, and Sequencing.

Complementing cosmids were restriction mapped by using sites unique to the pCDL04541 polylinker (ClaI, PstI, XhoI, and HindIII). Targeted fragments were subcloned into pBluescript II SK(+) (Stratagene) for DNA sequencing and/or into pCDL04541 for complementation analysis as described above. At least five putative Arabidopsis transformants of a dnd1/dnd1 line were obtained for most subclones. DNA sequencing was performed by using the BigDye Terminator Kit (PE Biosystems), M13 Forward and Reverse primers, and an ABI377 sequencing apparatus. Sequence data were analyzed by using Sequencher (Genes Code, Ann Arbor, MI) and publicly available blast programs (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). To sequence the dnd1-1 mutant allele, the primers 5′-TCTAGAGAAGTCCGTCCATCGAA-3′ and 5′-TCTAGAGCGATCTTTGAGGTTTGCTC-3′ were used along with Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene) to isolate a 5.3-kb PCR product from the Col-0 dnd1-1/dnd1-1 line. PCR products were directly sequenced by using additional primers internal to the DND1 gene. The single base difference between DND1 and dnd1-1 was confirmed by sequencing the relevant region of four independent PCR products.

Construction of dnd1 nahG+ Lines.

Arabidopsis Col-0 carrying the well characterized “B15” transgene insertion event of nahG+ under control of a 35S promoter was kindly provided by CIBA–Geigy/Novartis (Research Triangle Park, NC). A Ler-0 line carrying a similar construct with a different nahG gene was kindly provided by Xinnian Dong (Duke University, Durham, NC). Both lines were crossed to Col-0 dnd1-1/dnd1-1, and, for each cross, two separate experimental lines were derived by self-fertilization of F2 segregants homozygous for dnd1-1 and the nahG+ construct.

DNA Blot Analysis.

Total genomic DNA from a variety of plant species was restricted with HindIII and EcoRI (single-enzyme digests), was separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and was blotted and probed with a 32P-labeled version of the 5.3-kb DND1 PCR product described above or a full-length AtCNGC2 cDNA clone pAtCNGC2wt (kindly provided by of R. Mercier and G. Berkowitz, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT).

Results

Positional Cloning of DND1.

The dnd1 phenotypes are caused by a single locus recessive mutation in lines homozygous for the EMS-induced dnd1-1 mutant allele (5). Mapping with a population of 536 F2 individuals from a No-0 × Col dnd1-1/dnd1-1 cross had localized the dnd1 mutation to the genetic interval between markers CHS1 and nga106 on chromosome 5. The HR− and dwarf phenotypes were 100% linked (5). In the present study, we used a positional cloning approach to isolate and characterize the DND1 gene.

Initial efforts focused on identification of additional polymorphic markers in the CHS1-nga106 region. By using previously mapped markers, DND1 was placed between pCIT1243 (0.3 cM away) and CHS1 (1.3 cM away; see Fig. 1A).

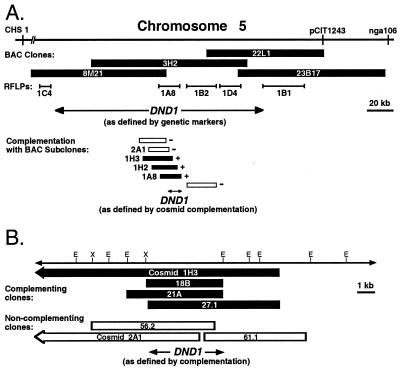

Figure 1.

Summary of positional cloning experiments leading to isolation of the DND1 gene. (A) CHS1, pCIT1243, and nga106 are previously mapped molecular genetic markers on Arabidopsis chromosome 5. pCIT1243 and nga106 were used to identify BAC clones carrying wild-type Col-0 genomic DNA inserts. Inserts from four BACs were subcloned to create a binary cosmid library; some of these cosmids were used as additional restriction fragment length polymorphism markers to refine the genetic interval containing DND1. Three cosmids that complement the dnd1 mutation were identified of 43 tested in a focused shotgun complementation project. (B) Higher-resolution complementation experiments using more precise subclones identified additional complementing and noncomplementing clones, including other clones not shown, that implicated an ≈5-kb region as the DND1 locus. This region encodes a previously identified cDNA named AtCNGC2. Cosmids 1H3 and 2A1 are shown in both A and B. E, EcoRI site; X, XbaI site.

Arabidopsis Col-0 genomic DNA BAC clones 8M21, 3H2, 22L1, and 23B17 were identified as optimally representing this region (Fig. 1A; see Materials and Methods). These BACs were then subcloned as 15- to 25-kb fragments in a transformation-competent binary vector. Restriction digest fingerprinting and hybridization to blots carrying restricted BAC DNA revealed that these subclone libraries were composed of at least 27, 29, 18, and 7 unique cosmid clones for 8M21, 3H2, 22L1, and 23B17, respectively, and that they provided substantial representation of the region of interest (data not shown).

The BAC-derived binary cosmid sublibrary facilitated further high-resolution mapping efforts. New restriction fragment length polymorphism markers were developed from five cosmids polymorphic between Col-0 and No-0. Cosmids 1C4 and 1B1 flanked informative recombination events from the mapping population whereas cosmids 1A8, 1B2, and 1D4 absolutely cosegregated with DND1 (Fig. 1A). Cosmids 1C4 and 1B1 defined a physical interval of roughly 150 kb spanning the DND1 locus.

A focused shotgun complementation strategy was pursued for identification of DND1 while the above mapping was in progress. Mutant dnd1 plants were transformed with individual cosmids from the BAC sublibraries, and primary transformants were then screened for reversion of the dwarf phenotype. As mapping proceeded, particular emphasis was placed on cosmids representing the region flanked by markers 1C4 and 1B1. For unknown reasons possibly related to the constitutive broad-spectrum resistance phenotype, dnd1 plants exhibited a low transformation rate relative to wild-type Col-0 (≈0.05% transformants per total number of seeds tested compared with ≈1% for Col-0). Although we generated transformants for only 43 cosmids across the contig, this was sufficient as T1 plants from cosmids 1A8 (BAC 3H2), 1H2 (BAC 3H2), and 1H3 (BAC 3H2) appeared to be complemented (n = 2 for each). These plants exhibited sizes similar to wild-type controls (Fig. 2; data not shown). These three cosmids all mapped physically to the same region of BAC 3H2 and displayed a high degree of overlap (Fig. 1A). T2 plants from each of the complemented lines segregated approximately 3:1 for size, reflecting the hemizygous nature of the T-DNA in the primary transformants (wild-type:dwarf segregation ratios = 23:6 for 1A8, 32:10 for 1H2, and 29:13 for 1H3). None of the transformants carrying the other 40 BAC-derived cosmids complemented the dnd1 mutation (Fig. 1A; data not shown). The region carrying the DND1 gene was delimited to approximately 10 kb by these positive and negative complementation results (Fig. 1A).

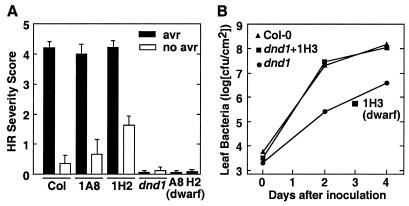

Figure 2.

Size-complementation of mutant dnd1 plants by addition of the cloned wild-type DND1 locus. Col-0 dnd1-1/dnd1-1 plants transformed with cosmids 1A8 or 1H2, or other complementing cosmids (not shown), corrected the dnd1 dwarf rosette phenotype.

Identification of the DND1 Gene.

Once complementing cosmids were identified, overlapping subclones from these cosmids were generated for precise gene identification by further complementation tests and DNA sequencing. By using a variety of restriction enzymes (see Materials and Methods), 0.6- to 9-kb fragments were subcloned in parallel into the binary vector pCLD04541 and into pBluescript II SK(+). Transformants of the dnd1 line were obtained for 14 subclones, and these transformants were examined for size complementation. Rosette size was quantified for these transformants, and significant differences from noncomplemented dnd1 controls were observed for some clones (Fig. 1B; data not shown). Identification of overlapping clones that complemented or failed to complement the dnd1 mutation suggested that DND1 resides partially or completely on a single 5.2-kb EcoRI/XbaI fragment (Fig. 1B).

After initially monitoring complementation of the dwarf phenotype, complementation of defense-related dnd1 phenotypes was confirmed in assays of HR tissue collapse and of resistance to virulent P. syringae. A strong HR was observed in response to P. syringae expressing avrRpt2 in T2 progeny of dnd1 lines that carried size-complementing transgene constructs whereas dwarf T2 segregants from the same hemizygous T1 parent retained the dnd1 HR− phenotype (Fig. 3A; data not shown). The constitutive resistance phenotype of mutant dnd1 plants was also eliminated (reverted to the wild-type phenotype) by complementation with the putative wild-type DND1 gene (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Complementation of the reduced-HR and constitutive resistance phenotypes of dnd1 plants by transformation with cloned wild-type DND1. (A) HR scores for leaves inoculated with P. syringae pv. glycinea Race 4 carrying cloned avrRpt2 (filled bars) or an empty plasmid vector (open bars). HR tissue collapse scored on a scale of 0–5 (0 = no visible collapse; 5 = confluent collapse of inoculated tissue; values are mean ± SE). Data are shown for T2 plants derived from hemizygous primary transformants; 1A8 (dwarf) and 1H2 (dwarf) represent control sets of T2 segregants that returned to the dnd1/dnd1 dwarf rosette size because of loss (via segregation) of the DND1 transgene. (B) Growth of virulent P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 in leaf tissue of inoculated plants. Col-0, wild type; 1H3, Col-0 dnd1/dnd1 line carrying wild-type DND1 because of transformation with cosmid 1H3; dnd1, Col-0 dnd1/dnd1; 1H3 (dwarf), dwarf-sized T2 plants from a Col-0 dnd1/dnd1 T1 transformant that was hemizygous for the introduced 1H3 construct.

Determination of the DNA sequence of the dnd1 complementing region and adjacent sequences from noncomplementing clones (GenBank accession number AF280939) revealed eight 83- to 675-bp stretches of sequence with 100% identity to the recently released nucleotide sequence of cDNA AtCNGC2 (GenBank accession nos. Y16328 and AF067798; refs. 36 and 37). These regions of identity, together with the intervening sequences that do not match AtCNGC2, reveal the intron/exon structure of a 3,327-bp DND1 gene composed of eight exons. The full-length AtCNGC2 cDNA, isolated independently by Köhler and Neuhaus (36) and Leng et al. (37), spans all but a 1.85-kb region at one end of the genomic segment defined by our complementing and noncomplementing subclones (Fig. 1B). No significant database matches or extensive open reading frames were observed in this non-AtCNGC2 region, and our clones 2A1 and 56.2 carried this genomic region but failed to complement the dnd1 mutation (Fig. 1B). These data indicate that DND1 encodes the AtCNGC2 cDNA. The derived DND1/AtCNGC2 amino acid sequence bears regions of similarity to animal cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels, and AtCNGC2 has been shown to encode a functional cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel (refs. 37 and 38; see Discussion).

The DNA sequence of the dnd1-1 mutant allele was determined to further test the above conclusions and to examine the nature of this defense-altering mutation. One base-change was detected in a region spanning the dnd1-1 gene as well as 1.4 kb of putative upstream controlling sequence and 400 bp of downstream sequence. The dnd1-1 allele contains a G to A point mutation that creates a stop codon in exon 3 at Trp290 (amino acid no. 290 of 720 total), presumably creating a severely truncated DND1 protein.

Depletion of Salicylic Acid.

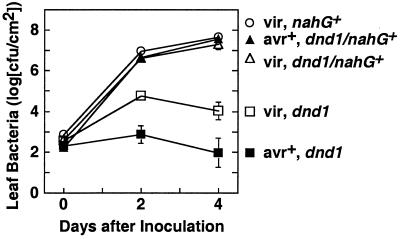

Previous work had determined that mutant dnd1 plants produce elevated levels of free- and glucoside-conjugated salicylic acid (5). To place the dnd1 mutation with respect to salicylate-mediated defense signaling pathways, we constructed plant lines homozygous for the dnd1-1 mutation and expressing nahG, a bacterial salicylate hydroxylase gene that causes depletion of salicylate levels (39). Expression of nahG disrupted both the elevated partial resistance against the normally virulent pathogen P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and the gene-for-gene resistance elicited in response to Pst DC3000 expressing avrRpt2 (Fig. 4). Similar loss of resistance was observed with other separately constructed dnd1/dnd1 nahG+ lines (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Loss of resistance in salicylate hydroxylase plants. Leaves were inoculated uniformly with virulent P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (open symbols) or Pst DC3000 avrRpt2+ (filled symbols). Squares, Col-0 dnd1/dnd1 line; circles, Col-0 nahG+ B15 line; triangles, Col-0 dnd1/dnd1, nahG+/nahG+ line. Leaf population data are shown as mean ± SE.

Despite the strong impact on disease resistance, other dnd1 phenotypes were not fully reverted to wild-type by removal of salicylic acid. The dnd1/dnd1 nahG+ lines reproducibly grew with a “semidwarf” leaf and rosette size that was intermediate between wild-type and the dwarfed dnd1/dnd1plants. The loss-of-HR phenotype of dnd1 mutants also remained in dnd1/dnd1 nahG+ plants. Depletion of SA by nahG has been previously reported to disrupt the HR (40). In wild-type plants carrying nahG+, we found that the HR was not entirely abolished but, rather, was delayed such that tissue collapse was evident 48 h rather than 24 h after high-titer inoculation with Psg R4 carrying avrRpt2 (Table 1). However, in dnd1/dnd1 nahG+ lines, we observed that no HR developed, even at 48 h after inoculation (Table 1).

Table 1.

HR in plant lines depleted of salicylic acid by expression of nahG

| Plant line* | 24 hr

|

48 hr

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| avrRpt2+ | no avr | avrRpt2+ | no avr | |

| Col-0 | H5† | H0 | H5 | H0.5 |

| dnd1 | H0 | H0 | H0 | H0 |

| nahG | H0.5 | H0 | H5 | H2 |

| dnd1 + nahG‡ | H0 | H0 | H0.1 | H0 |

Plant lines wild-type Col-0 or Col-0 homozygous for nahG+ transgene and/or dnd1-1 mutation.

† H, average HR severity, scored on 0–5 scale (H0 = no HR; H5 = confluent collapse), after inoculation with 108 colony-forming units/ml Psg R4 carrying pV288 or pVSP61.

‡ Data pooled for four independent lines.

DND1 in Other Plant Species.

To examine the occurrence of DND1 homologues in crop species, genomic DNA blots were probed with Arabidopsis DND1 gene probes. When a cDNA clone was used as probe and blots were washed at moderate stringency (5 × SSC/65°C or 1 × SSC/65°C), only bands corresponding to the known DND1 genomic locus were observed in Arabidopsis samples (data not shown). A single weakly hybridizing band was observed in Brassica napus and radish but not other species (listed below). Use of a cDNA clone was important because, in blots probed with labeled genomic DND1 (containing coding region, ≈1.4 kb of promoter and ≈0.4 kb of 3′ sequence) and washed at high stringency (0.1 × SSC, 65°C), discrete hybridizing bands were clearly present in DNA from soybean, potato, tomato, tobacco, alfalfa, radish, B. napus, rice, maize, and oats (data not shown).

Conditional Lesion Mimicry in dnd1 Plants.

In earlier work with non-inoculated dnd1 mutant plants grown in a variety of environments in the U.S. and U.K., no substantive leaf flecking, necrotic spotting, or other lesion-mimic phenotypes were observed upon inspection by naked eye or in microscopic studies using autofluorescence or trypan blue staining (5). However, in our new laboratory facilities at University of Wisconsin, we observed leaf lesions in some batches of non-inoculated dnd1 plants. These lesions were pinpoint in size (≈10–50 dead cells) and did not enlarge or coalesce after initial formation. Lesions did not form on control Col-0 plants grown in parallel. Lesion formation was associated with growth of young plants at light intensities of ≈250 μE/m2 at low relative humidity in a rapid-drying soil mix, but the vast majority of dnd1 plants (including plants grown under similar conditions) have not exhibited lesions. Some but not all colleagues working with dnd1 plants at other locations have also observed lesions. Arabidopsis dnd1-1/dnd1-1 apparently can be classified as a rare/conditional lesion-mimic line.

Discussion

In an effort to understand the resistance induction and HR-suppression phenotypes of mutant dnd1 plants, we sought to molecularly characterize the Arabidopsis DND1 gene. A positional cloning effort identified overlapping genomic DNA subclones from the DND1 locus that, when transformed into dnd1/dnd1 plants, cause reversion from dwarf to wild-type rosette size, recovery of the HR, and loss of the constitutive resistance to virulent P. syringae. DNA sequencing revealed that DND1 encodes a cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel identical to the product of AtCNGC2, a characterized cDNA of previously unknown organismal function (36, 37). The dnd1-1 mutant allele carries a single nucleotide change that causes a premature stop codon within the DND1/AtCNGC2 sequence.

Cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) ion channels are very well known from studies of animal systems, where they play central roles in visual and olfactory signal transduction (41, 42). Although CNG ion channels have many structural similarities to voltage-gated ion channels, they are gated primarily by binding of a cytoplasmic ligand (cAMP or cGMP) rather than by voltage. The channels are semiselective cation channels that allow permeation of Ca2+, K+, Na+, and other ions, but, in the more well studied examples, their primary physiological activity is to allow movement of Ca2+ into cells. CNG ion channels have a characteristic structure in which a cytoplasmic amino terminus is followed by six membrane-spanning domains and a cytoplasmic carboxyl terminus of substantial length (200+ amino acids) that carries the cyclic nucleotide binding domain. Upon multimer formation, a pore-forming domain is apparently formed by characteristic amino acid sequences between the fifth and sixth membrane-spanning domains. Some of these CNG ion channels also carry a calmodulin-binding domain within their amino terminus and can be regulated by intracellular Ca2+ levels (41–43).

AtCNGC2 was recently identified by two separate groups via searches of the Arabidopsis EST database (44) for entries with similarity to animal cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels; recovery of homologous full-length cDNA clones yielded AtCNGC2 (36, 37). Köhler et al. identified six apparent cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel genes from Arabidopsis (38) and more such genes are present in the Arabidopsis genome, but the DND1/AtCNGC2 derived amino acid sequence is only 42–43% similar to most of these other genes. Intriguingly, AtCNGC1, -2, -3, and -4 are unlike previously described CNG channels in that they carry a putative calmodulin-binding domain within their carboxyl terminus at a location that physically overlaps the putative cyclic nucleotide binding domain. Yeast two-hybrid experiments were used to document physical interaction between Arabidopsis calmodulins and a carboxyl-terminal AtCNGC2 construct (38). Complementation of a yeast K+-uptake mutant by AtCNGC2 was found to depend on supplementation with membrane-permeable cAMP or cGMP (37). Importantly, voltage clamp analysis using transfected Xenopus oocytes or human embryonic kidney cells demonstrated that AtCNGC2 fosters Ca2+ and K+ influx in a cyclic nucleotide-dependent fashion (37). This was the first functional demonstration of a CNG ion channel from plants.

Based on the above findings, we hypothesize that DND1 encodes a functional cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel. The defense-altering dnd1 mutation is recessive (5), and it creates a stop codon before the pore-forming domain between the fifth and sixth putative membrane-spanning domains of AtCNGC2. These findings make it less likely that dnd1 phenotypes are caused by a leaky or misfunctional channel and suggest instead that the dnd1 mutation causes a complete absence of functional AtCNGC2 ion channels.

The dnd1 mutation apparently acts upstream of salicylic acid, as transformation of dnd1 mutants with nahG+ (salicylate hydroxylase) substantially removed the constitutive-resistance of dnd1 mutants. However, the loss-of-HR and dwarf rosette phenotypes of dnd1 mutants were not entirely corrected by nahG+. Preliminary studies indicated that SA levels were reduced to the limits of detection in dnd1/dnd1 nahG+ lines (I-c.Y., K.A.F., S. Sharma, D. Klessig, and A.F.B., unpublished work), implying that the dwarfing and loss-of-HR caused by the dnd1 mutation are elicited at least in part via salicylate-independent pathways. The responsiveness of wild-type DND1/AtCNGC2 protein to cyclic nucleotides and calmodulin implies that some aspects of DND1 channel regulation lay downstream of phenomena that alter levels cyclic nucleotides and Ca2+.

A number of testable models can be proposed to explain how genetically recessive absence of an ion channel might activate constitutive broad-spectrum resistance or cause disruption of HR cell death. Ca2+ influx is a critical early step in defense activation processes (discussed in the introduction), and DND1 may encode channels that participate directly in pathogen-induced Ca2+ influx. However, a straightforward universal requirement of DND1 channels for defense activation is unlikely. Although HR cell death is blocked, defense processes proceed and in fact are potentiated in dnd1 plants.

It is challenging to build models that explain the simultaneous activation of defenses and loss of HR in mutant dnd1 plants. It may be that a number of defense responses are constitutively activated in dnd1 mutants and that among these responses is an elevation of HR-blocking cellular protection processes such as elevated levels of catalase, glutathione S-transferase, or ascorbate peroxidase. Defense activation may arise because absence of the DND1 channel alters normal levels of specific ions, mimicking defense-inducing physiological states. For example, if DND1 is an inward-rectifying K+ channel, it is possible that the reduced ability of dnd1 plants to take up K+ mimics the ionic environment observed during early stages of infection by pathogens (in which K+ efflux leads to lower than normal intracellular K+ concentrations; refs. 3 and 20), producing constitutive defense signaling and constitutive systemic resistance. Wild-type DND1 may function in homeostasis, reestablishing ionic balance after defense activation and/or other stimuli.

It is also possible that the defense-altering phenotypes of dnd1 plants are the product of unrelated processes precipitated by loss of DND1: i.e., that the wild-type DND1/AtCNGC2 ion channel normally functions in processes that have little or no direct relationship to plant defense responses. However, even an indirect relationship between DND1 and defense signaling does not alter the fact that defenses are significantly altered in the dnd1 mutant. Our work demonstrates that perturbation of a specific CNG ion channel can activate broad-spectrum disease resistance and can perturb HR cell death in higher plants.

The dnd1 plants are of interest as a starting point for further examination of cell death and defense activation events. For example, Heo et al. have recently demonstrated the participation of specific calmodulin isoforms in the activation of defense responses (45), and it would be of interest to examine calmodulin-related defense signaling with respect to DND1. Work from both plant and animal systems has focused attention on the relationships between cyclic nucleotides, calcium signaling, ion channel activation, generation of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species, and the activation of apoptotic cell death and disease resistance (46–50). Plants mutated at DND1 may be well suited for additional biochemical and genetic studies that address these topics.

A large volume of previous work has generated evidence for the participation of ion fluxes in defense activation or has suggested that these ion fluxes represent important stages in pathogen-induced host cell necrosis or in HR cell death (16, 17, 28). Much of the more precise defense signal transduction work involving ion fluxes has been performed by using isolated plant cells and/or pharmacological approaches. Work with a genetic component has typically exploited genotypes that alter disease resistance rather than genotypes that directly control ion fluxes. Study of dnd1 has provided a line of evidence for the involvement of ion channels in defense activation, providing a genetic system in which direct perturbation of an ion channel profoundly influences plant disease resistance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Novartis Corporation and Xinnian Dong for sharing nahG+ Arabidopsis lines and R. Mercier and G. Berkowitz for the gift of an AtCNGC2 cDNA clone. This work was supported in part by grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture/National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program (Plant Pathology) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (National Institutes of Health), and a departmental graduate fellowship to K.A.F. sponsored by Pioneer Hi-Bred International, Inc.

Abbreviations

- HR

hypersensitive response

- BAC

bacterial artificial chromosome

- CNG

cyclic nucleotide-gated

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. AF280939).

Article published online before print: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.150005697.

Article and publication date are at www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.150005697

References

- 1.Hammond-Kosack K E, Jones J D G. Annu Rev Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:575–607. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin G B. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1999;2:273–279. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(99)80049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman R N, Novacky A J. The Hypersensitive Reaction in Plants to Pathogens: A Resistance Phenomenon. St. Paul, MN: Am. Phytopathol. Soc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richberg M H, Aviv D H, Dangl J L. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1998;1:480–485. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(98)80039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu I-c, Parker J, Bent A F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7819–7824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohm B A, Goulden M G, Gilbert J E, Kavanagh T A, Baulcombe D C. Plant Cell. 1993;5:913–920. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.8.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bendahmane A, Kanyuka K, Baulcombe D C. Plant Cell. 1999;11:781–791. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.5.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Century K S, Holub E B, Staskawicz B J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6597–6601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Y, Shah J, Klessig D F. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1621–1639. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glazebrook J. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1999;2:280–286. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(99)80050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryals J L, Neuenschwander U H, Willits M C, Molina A, Steiner H-Y, Hunt M D. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1809–1819. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu I-c, Fengler K A, Clough S J, Bent A F. Mol Plant–Microbe Interact. 2000;13:277–286. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg J T. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:525–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rate D N, Cuenca J V, Bowman G R, Guttman D S, Greenberg J T. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1695–1708. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.9.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamb C, Dixon R A. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:251–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheel D. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1998;1:305–310. doi: 10.1016/1369-5266(88)80051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammond-Kosack K E, Jones J D G. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1773–1791. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahlbrock K, Scheel D, Logemenn E, Nurnberger T, Papniske M, Reinhold S, Sacks W R, Schmelzer E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4150–4157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu H, Heath M C. Plant Cell. 1998;9:249–259. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.4.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atkinson M M, Keppler L D, Orlandi E W, Baker C J, Mischke C F. Plant Physiol. 1990;92:215–221. doi: 10.1104/pp.92.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atkinson M M, Midland S L, Sims J J, Keen N T. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:297–302. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.1.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He S-Y, Huang H-C, Collmer A. Cell. 1993;73:1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90354-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine A, Pennell R I, Alvarez M E, Palmer R, Lamb C. Curr Biol. 1996;6:427–437. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00510-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nurnberger T, Nennstiel D, Jabs T, Sacks W R, Hahlbrock K, Scheel D. Cell. 1994;78:449–460. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romeis T, Piedras P, Zhang S, Klessig D F, Hirt H, Jones J D. Plant Cell. 1999;11:273–287. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.2.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ligternik W, Kroj T, zur Neiden U, Hirt H, Scheel D. Science. 1997;276:2054–2057. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jabs T, Tschöpe M, Colling C, Hahlbrock K, Scheel D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4800–4805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ebel J, Scheel D. The Mycota, Vol. V: Plant Relationships, Part A. Berlin: Springer; 1997. pp. 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gabriel D, Rolfe B. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1990;28:365–391. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current Protocols In Molecular Biology. New York: Wiley; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marra M, Kucaba T, Sekhon M, Hillier L, Martienssen R, Chinwalla A, Crockett J, Fedele J, Grover H, Gund C, et al. Nat Genet. 1999;22:265–270. doi: 10.1038/10327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mozo T, Fischer S, Meier-Ewert S, Lehrach H, Altmann T. Plant J. 1998;16:377–384. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bancroft I, Love K, Bent E, Sherson S, Lister C, Cobett C, Goodman H M, Dean C. Weeds World. 1997;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koncz C, Schell J. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;204:383–396. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clough S J, Bent A F. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Köhler C, Neuhaus G. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:1604. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leng Q, Mercier R W, Yao W, Berkowitz G A. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:753–761. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.3.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Köhler C, Merkle T, Neuhaus G. Plant J. 1999;18:97–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaffney T, Friedrich L, Vernooij B, Negrotto D, Nye G, Uknes S, Ward E, Kessmann H, Ward J. Science. 1993;261:754–756. doi: 10.1126/science.261.5122.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delaney T P, Uknes S, Vernooij B, Friedrich L, Weymann K, Negrotto D, Gaffney T, Gutrella M, Kessmann H, Ward E, et al. Science. 1994;266:1247–1250. doi: 10.1126/science.266.5188.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zagotta W N, Siegelbaum S A. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:235–263. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.001315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Broillet M C, Firestein S. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;868:730–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zielinski R E. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1998;49:697–725. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newman T, de Bruijn F J, Green P, Keegstra K, Kende H, McIntosh L, Ohlrogge J, Raikhel N, Somerville S, Thomashow M, et al. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1241–1255. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heo W D, Lee S H, Kim J C, Chung W S, Chun H J, Lee K J, Park H C, Park C Y, Choi J Y, Cho M J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:766–771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Delledonne M, Xia Y, Dixon R A, Lamb C. Nature (London) 1998;394:585–588. doi: 10.1038/29087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Durner J, Wendehenne D, Klessig D F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10328–10333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mason R P, Leeds P R, Jacob R F, Hough C J, Zhang K G, Mason P E, Chuang D M. J Neurochem. 1999;72:1448–1456. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.721448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmid-Antomarchi H, Schmid-Alliana A, Romey G, Ventura M A, Breittmayer V, Millet M A, Husson H, Moghrabi B, Lazdunski M, Rossi B. J Immunol. 1997;159:6209–6215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alvarez M E, Pennell R W, Meijer P-J, Ishikawa A, Dixon R A, Lamb C. Cell. 1998;92:773–784. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]