Abstract

The ribosomal protein S13 is found in the head region of the small subunit, where it interacts with the central protuberance of the large ribosomal subunit and with the P site-bound tRNA through its extended C terminus. The bridging interactions between the large and small subunits are dynamic, and are thought to be critical in orchestrating the molecular motions of the translation cycle. S13 provides a direct link between the tRNA-binding site and the movements in the head of the small subunit seen during translocation, thereby providing a possible pathway of signal transduction. We have created and characterized an rpsM(S13)-deficient strain of Escherichia coli and have found significant defects in subunit association, initiation and translocation through in vitro assays of S13-deficient ribosomes. Targeted mutagenesis of specific bridge and tRNA contact elements in S13 provides evidence that these two interaction domains play critical roles in maintaining the fidelity of translation. This ribosomal protein thus appears to play a non-essential, yet important role by modulating subunit interactions in multiple steps of the translation cycle.

Keywords: ribosome, translation, subunit interface, rpsM(S13), fidelity

Abbreviations used: cryEM, cryo-electron microscopy; EF, elongation factor; IF, initiation factor; TLC, thin-layer chromatography

Introduction

Translation of the genetic code is catalyzed by the RNA:protein machine known as the ribosome. The ribosome is composed of two distinct subunits and the process of translation relies on coordinated movements of these subunits with the mRNA and tRNA substrates of translation. Structural and biochemical data provide strong evidence that distinct regions of the ribosome comprising both rRNA and ribosomal proteins located on the subunit interface play a functional and dynamic role in all of the steps in translation.1–4 Further definition of the mechanics of translation will depend on a detailed understanding of the thermodynamics and kinetics of these specific molecular interactions and on the signals that coordinate their movement.

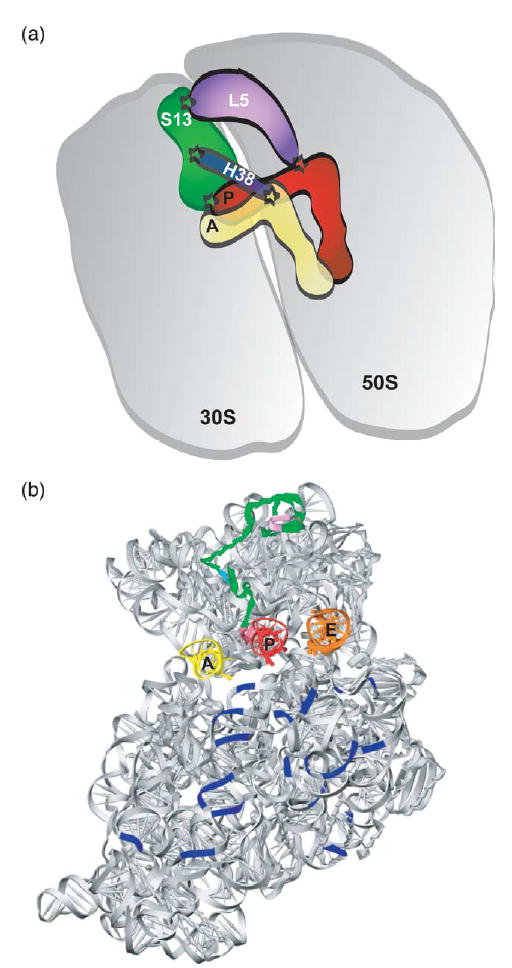

An interesting molecular candidate that likely plays a functional, as well as structural, role at the subunit interface is the small subunit ribosomal protein S13. X-ray crystallographic evidence places this protein on the subunit interface in the head of the small subunit.5 There, S13 contacts the large subunit of the ribosome in the central protuberance and forms two specific bridges, 1a and 1b, that were identified first by cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM)6–8 and subsequently by X-ray crystallography.1 These S13-mediated bridges are the only direct contacts between the head and central protuberance regions of the small and large subunits of the ribosome. Bridge 1a connects the middle of S13 (around residue 93) to helix 38 (H38) of the 23 S rRNA and bridge 1b connects the N terminus of S13 to the large subunit protein L5. These regions of the large subunit, helix 38 and protein L5, are of particular interest because they make direct contacts with the A-site and P-site tRNAs bound to the large subunit, respectively.1 Further, previous cryoEM studies have suggested that the head and the central protuberance regions of the small and large subunits, respectively, are mobile and “ratchet” during translocation.9 Additionally, the C terminus of S13 contacts the anticodon stem of the P-site tRNA around nucleotide 36 (within the small subunit), providing a potential direct link between tRNA movements deep within the small and large subunits and mobile external elements of the ribosome. While it is clear that S13 is poised to make important contributions to ribosome interactions fundamental to function, a next step is to define the magnitude and dynamics of these contributions during the specific steps of translation.

Translocation describes the coupled three nucleotide movement of the mRNA:tRNA complex through the densely packed interface of the ribosome and is a step where S13-mediated interactions are likely to play a significant role. Molecular insights into translocation have been obtained recently from cryoEM structures of the ribosome in initiation-like and elongation factor G (EF)-G·GTP-bound states. In comparing these two states, S13 “stood out among all the proteins of the 30 S small subunit by displaying the largest [−15 Å] movement” upon EF-G binding.10 Indeed, the ratcheting movement of the head of the ribosome appears to break bridge 1a and the residues comprising bridge 1b change as well. Previous studies using an in vitro reconstitution system showed that S13 contributes to the stability of the pre-translocation state.11 In these studies, exclusion of S13 and another small subunit protein S12 from a reconstituted small subunit particle led to substantial translocation activity even in the absence of EF-G. These data suggest that S13 may play a direct role in modulating the rate and efficiency of translocation.

The initiation of translation depends critically on the ordered assembly of a complex composed of a 70 S ribosome particle bound to an mRNA with an AUG codon bound by an initiator tRNA, and is another step where S13 may play a significant role. The initiation process is orchestrated by at least three distinct initiation factors (IF) in bacteria, IF1, IF2 and IF3, that somehow regulate the overall process and modulate the intrinsic association between the two subunits. IF3 disfavors subunit joining by binding directly to the small subunit interface in the platform region.12–14 IF3 is proposed to play a crucial role in promoting subunit dissociation and thus is fundamental to the process of ribosome recycling.15 IF1 binds in the A-site region of the small subunit, disfavoring subunit association and premature binding of tRNAs in the A site before the initiator tRNA has bound.16 While the role of IF2 has been controversial,17,18 IF2 appears to use the energy of GTP hydrolysis to facilitate the subunit joining step of initiation. The initiation process must be fast and efficient, and must ensure the accuracy and composition of the complex. It follows that the energy of association provided by the intersubunit bridges is a carefully balanced quantity; too much energy in the interaction might allow for promiscuous or premature association, while too little might hinder efficient initiation. The bridge contacts mediated by S13, 1a and 1b, are poised to play a critical role in maintaining this balance.

In order to define the specific contributions made by the various structural elements of S13 to subunit association and ribosome function, we have performed experiments using in vivo assembled ribosomes from Escherichia coli carrying a genetic deletion of the rpsM gene (S13). This genetic manipulation allowed us to characterize the in vivo and in vitro consequences of loss of the S13 protein. In a second set of experiments, targeted mutagenesis of the bridge and C-terminal extension regions of the S13 protein probed the role of these specific elements in ribosome function.

Results

Construction of an S13 deletion strain

To investigate the role that S13 plays in the ribosome, we constructed an E. coli strain with an rpsM (S13) genomic deletion. The details of the strain construction can be found in Materials and Methods. Briefly, we used the Datsenko & Wanner system19 to insert a selectable kanamycin marker at the S13 locus while complementing for the genomic deletion with a plasmid-encoded S13 gene under the control of the IPTG-inducible trp/lac (trc) promoter.20 The resulting strain displayed IPTG-dependent growth and the placement of the kanamycin cassette in the alpha (S13) operon was established by PCR analysis and direct sequencing of the region of interest (data not shown).

To create an rpsM deletion strain, the kanamycin marker was moved into an E. coli strain (MG1655) not carrying the plasmid-encoded rpsM by generalized P1 transduction. The placement of the kanamycin cassette in the genome at the S13 locus was again confirmed by PCR analysis and sequencing. The absence of rpsM was verified by Southern blot analysis and by PCR amplification schemes (data not shown).

The growth of the rpsM-deficient strain is impaired severely, with a doubling time of 130 minutes compared to the wild-type doubling time of 25 minutes (Table 1). Growth is rescued readily in the deletion strain by transformation of an S13-containing plasmid (doubling time of 35 minutes).

Table 1.

The growth rates of the parental strain (MG1655), the rpsM knockout, and the rpsM knockout carrying a plasmid encoded rpsM gene in rich LB medium

| Strain | Plasmid | Doubling time (minutes) |

|---|---|---|

| MG1655 | 25±3 | |

| MG 1655 ΔrpsM::kan (S13MG1) | 130±12 | |

| MG 1655 ΔrpsM::kan (S13MG1) | pTRC S13 | 35±3 |

S13 is not essential for growth of E. coli

Because of the general slow growth of the S13 knockout strain as well as its heterogeneous colony size on plating, we wondered if the S13 knockout strain that we had constructed contained extragenic suppressor mutations and if S13 was, in fact, an essential gene. In order to determine whether the S13 knockout strain depended upon extragenic suppressor mutations to live, we performed a simple cotransduction experiment. A strain was constructed with a tetR gene closely linked to the S13::kanR marker, and complemented with the S13 plasmid. A P1 lysate from this strain was used to infect either MG1655, a wild-type strain or, as a control, the same strain with a plasmid-encoded rpsM gene. The resulting transductants were selected on tetracycline plates. We then asked what fraction of the tetR clones was also kanR. If growth of the rpsM knockout strain depended on an extragenic suppressor, then the frequency of finding the kan marker in a tetR clone should depend on the frequency of the second site mutation arising spontaneously in the recipient strain, and this should be very low. However, if rpsM was a non-essential gene, the frequency of cotransduction should depend only on the distance between the two markers, and therefore should be the same, independent of whether strain MG1655 carried an rpsM plasmid. For the wild-type uncomplemented strain, a cotransduction frequency of 24% (16/66) was found, whereas in the complemented strain (carrying the S13 plasmid) a cotransduction frequency of 28% (18/66) was found. On the basis of map distances between the kanR marker and the tetR marker (59 minutes),21 we would expect a cotransduction frequency of approximately 34%. The similar cotransduction frequency between the plasmid-containing and non-plasmid-containing strains indicates that S13 is not essential for the growth of E. coli.

Ribosomes lacking S13 display a subunit association defect in vitro

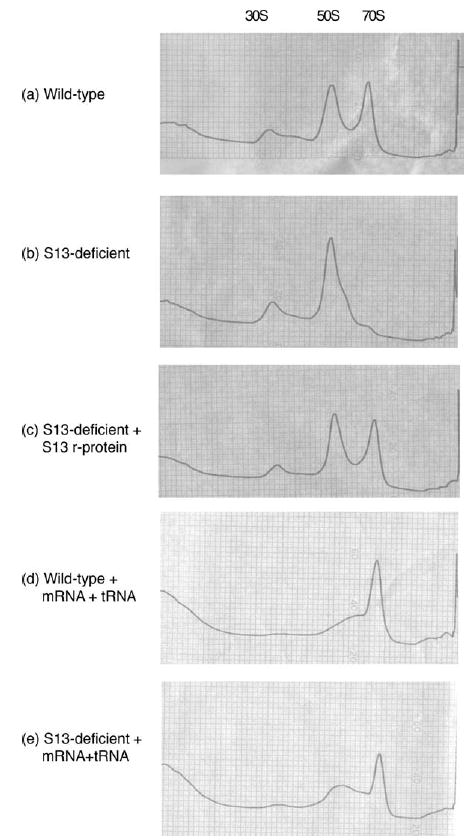

To investigate the role that S13 plays in subunit association, we analyzed the formation of 70 S ribosomal particles from individual subunits using sucrose gradient sedimentation analysis. The association between the large and small subunits is magnesium-dependent in vitro; in high concentrations of magnesium (>10 mM) most of the subunits are joined in 70 S complexes, while the subunits do not associate in low concentrations of magnesium (1 mM). We found that small subunits lacking S13 associated poorly with large subunits under all conditions; there was no clear 70 S complex peak in the gradient profiles when compared with those of wild-type ribosome particles (Figure 1(a) and (b)). In order to test whether the defect in subunit association was attributable directly to the absence of S13 protein, we added purified recombinant S1322 to the S13-deficient 30 S particles and examined subunit association by sucrose gradient analysis. The incubation with S13 restored subunit association to wild-type levels so that a clear 70 S peak is now evident (Figure 1(c)). These data demonstrate that the presence of S13 in the 30 S subunit is critical for robust 70 S complex formation. The simplest explanation for these data is that the S13-dependent bridges in the head of the ribosome (bridges 1a and 1b) provide significant stabilization to the 70 S ribosome structure.

Figure 1.

Subunit association of MRE600 50 S ribo-somes in associating conditions (15 mM MgCl2) with (a) wild-type MG1655 30 S, (b) rpsM-deficient MG1655 30 S and (c) rpsM-deficient MG1655 30 S pre-incubated with recombinant S13 protein. (a)–(c) These experiments were performed in the absence of mRNA and tRNA, and repeated in their presence for (d) MG1655 wild-type and (e) MG1655 S13-deficient subunits. In these experiments, 30 S and 50 S subunits were allowed to associate for one hour at 37 °C and then loaded onto a 10%–40% (w/v) sucrose gradient for ultracentrifugation.

The ability of cells lacking S13 to survive in vivo suggests that the gross subunit association defect observed in vitro is somehow compensated for in vivo. We reasoned that in the presence of other components such as mRNA, tRNA or IFs, subunit association might be sufficiently stable for the ribosome to perform its requisite tasks. In order to test this hypothesis, we bound a model mRNA, gene 32, and N-Ac-Phe-tRNAPhe to the ribosomes of interest to mimic a functional translation complex and then analyzed the complexes by sucrose gradient sedimentation. Indeed, the presence of tRNA and mRNA was sufficient to restore 70 S complex formation to S13-deficient ribosomes (Figure 1(d) and (e)). These data suggest that, although S13 plays an important role in facilitating intersubunit interaction, the stability of subunit association is determined by multiple components in the system.

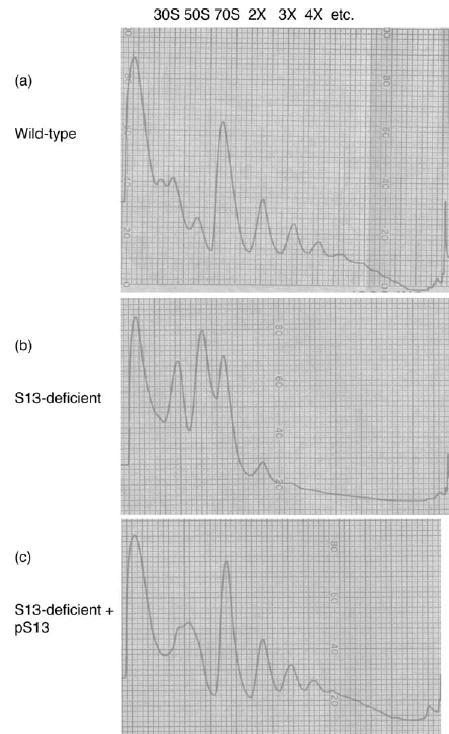

Polysome profiles of cells lacking S13 display gross subunit association defects in vivo

Due to the strong subunit association defect seen in vitro in particles that lack S13, we examined the polysome profiles of cells that lack S13 to determine the effect that S13 is having on the translation status of cells in vivo. Chloramphenicol was added to actively growing cells to stall protein synthesis and allow for the analysis of the distribution of ribosomes in the cell by sucrose gradient sedimentation (Figure 2(a) and (b)). Cells lacking S13 have similar quantities of 70 S ribosomes compared with wild-type cells but display a substantial deficit of polysomes (very few di-somes and no higher-order assemblies) and an abundance of free 30 S and 50 S subunits. Again, in order to establish that this defect is attributable directly to the lack of S13 protein, and not, for example, the result of polarity effects on the alpha operon, we repeated the experiment with the complemented strain carrying an S13 plasmid vector (Figure 2(c)). The introduction of S13 restores the overall properties of the polysome profile to those of a wild-type population, where polysome content is increased at the expense of free 30 S and 50 S subunits. These data indicate that the phenotypic defects observed in the polysome profile are directly attributable to the lack of S13.

Figure 2.

Polysome profiles of (a) wild-type MG1655 cells, (b) rpsM-deficient MG1655 cells (S13MG1), and (c) rpsM genomic knockout (S13MG1) with a plasmid-encoded rpsM gene (pTRCS13). Translation was stalled during logarithmic growth with the addition of chloram-phenicol (100 mg/l), cells were lysed and loaded onto a 10%–40% (w/v) sucrose gradient.

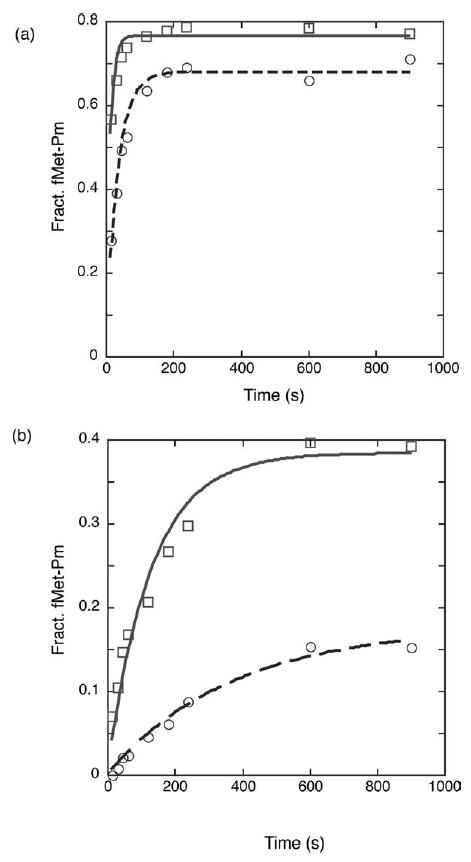

Initiation complex formation is defective in ribosomes lacking S13

To examine the role that S13 might play in the initiation step of translation, we set out to examine the relative rates at which wild-type and S13-deficient ribosomes form active initiation complexes. In particular, we were interested in the effects of S13 on the rate at which the 30 S initiation complex joins with the 50 S subunit to form a competent elongation complex. The subunit-joining step of this reaction is specifically promoted by IF2 using the energy of GTP hydrolysis, and it is this step that we reasoned might be compromised in an S13-deficient background.18 For this assay, we incubated 30 S subunits (wild-type and S13-deficient) with fMet-tRNAfMet, IF1, IF2·GTP, IF3 and gene 32 mRNA to form the pre-initiation complex. We then added 50 S subunits and the minimal A-site substrate puromycin and followed the formation of dipeptide (fMet-Pm) by electrophoretic thin-layer chromatography (TLC).23 Because interaction between the two subunits is known to be strongly magnesium-dependent, we chose to perform these experiments in high-stringency low-magnesium (3.5 mM) buffer,24 as well as in a lower stringency buffer where the concentration of magnesium was increased to 7 mM.25 Under stringent conditions, there are clear defects in the rate of formation of fMet-Pm by S13-deficient ribosomes either in the presence (Figure 3(a)) or (Figure 3(b)) in the absence of initiation factors. Similar results were obtained under the lower stringency conditions (data not shown). In independent experiments, we have shown that pre-formed 70 S ribosome complexes containing S13-deficient ribosomes exhibit no discernible deficits in peptidyl transferase activity (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Monitoring subunit association and initiation as measured by fMet-Puro formation in wild-type (□/continuous lines) and rpsM-deficient (○/broken lines) 30 S subunits. (a) The 30 S subunits, initiation factors 1, 2, and 3 (3 μM) and GTP (1 mM) in high-stringency24 buffer were pre-incubated and then mixed with 50 S subunits and puromycin (4 mM). Curve-fitting to a single exponential yields a rate constant of 0.08 s−1 for wild-type and 0.03 s−1 for rpsM-deficient. (b) The reaction was repeated in the same conditions in the absence of the three initiation factors and GTP. Curve-fitting to a single exponential yields a rate constant of 0.008 s−1 for wild-type and 0.003 s−1 for rpsM-deficient.

The observed defects in these initiation-related assays are consistent with the defects that we saw in subunit association both in the in vivo derived polysome profiles and in the in vitro sucrose gradient association experiments. The S13-deficient ribosomes have clear defects in subunit joining that are likely to result in substantial defects in initiation in vivo and may explain, in part, the extremely slow growth-rates of S13-deficient cells.

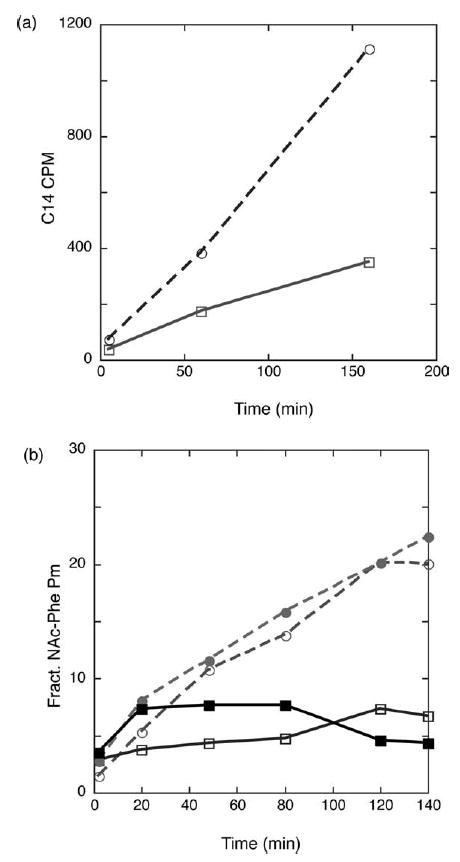

Ribosomes lacking S13 display increased rates of factor-independent translocation

Previous work has characterized the role that S13 plays in conjunction with S12 in maintenance of the pre-translocation state.11 Here, we used two assays to characterize the ability of these in vivo derived S13-deficient ribosomes to maintain a stable pre-translocation state. First, we used a simple polyuridine-based polyphenylalanine translation system to look at the rates of factor-independent (without EF-G or EF-Tu) translation by the wild-type and S13-deficient ribosomes.26 Second, we used a single-turnover translocation experiment to assess this specific step of elongation in these same ribosome populations.26

In the multiple turnover polyphenylalanine synthesis reaction, wild-type and S13-deficient ribosomes were incubated with Phe-tRNAPhe and a poly(U) mRNA, and the amount of (Phe)n peptide produced over time was assessed by precipitation in trichloroacetic acid (TCA). As seen in Figure 4(a), the S13-deficient ribosomes display two- to threefold increases in the rates of factor-independent translation. We next performed several single-turnover reactions designed to more specifically examine the stability of the pre-translocation state. In these experiments, a pre-translocation ribosome complex is assembled carrying a deacylated tRNA species in the P site and a peptidyl tRNA mimic in the A site. In this complex, the peptidyl moiety is unreactive with puromycin, even over extended periods of time.27 However, following translocation either by EF-G or by factor-independent movements, the peptidyl moiety becomes reactive and so dipeptide formation can be used to assess translocation indirectly.

Figure 4.

Analysis of spontaneous translocation in wild-type (▪/□/continuous lines) and S13-deficient ribosomes (•/○/broken lines). (a) Spontaneous translocation as measured in a multiple turnover poly-phenylalanine assay. Amount of TCA-precipitable poly-phenylalanine produced by either rpsM-deficient or wild-type ribosomes when incubated with poly(U) mRNA and charged Phe-tRNAPhe in the absence of EF-G, EF-Tu and GTP. (b) Spontaneous translocation as measured by the reactivity of the pre-translocation state with puromycin. The pre-translocation state was formed with deacylated tRNA in the P site (either tRNAPhe or tRNAf Met), N-Ac-Phe-tRNAPhe in the A site on either a poly(U) (•/▪) or a gene 32 mRNA (λ/ν).

Pre-translocation complexes were formed by incubating ribosomes with mRNA (either gene 32 or poly(U)) and excess deacylated tRNA (tRNAfMet or tRNAPhe, respectively) to fill the P site and then adding N-Ac-Phe-tRNAPhe to form the pre-translocation state. With both complexes (the gene 32 or poly(U) defined systems), ribosomes lacking S13 show a clear increase in puromycin reactivity over time in the absence of elongation factors compared to wild-type ribosomes (Figure 4(b)). The addition of the translocation-specific antibiotic thiostrepton reduces the puromycin reactivity, suggesting that the observed increase in reactivity is the result of authentic translocation (and not, for example, tRNA rebinding following a dissociation event).26 Both the single and multiple-turnover experiments described here are consistent with our earlier work indicating that S13 makes critical contributions to the maintenance of the pre-translocation state.11

We were interested in knowing whether the absence of S13 resulted in detectable consequences on EF-G-mediated translocation. In a first assay, we set up pre-translocation state ribosome complexes (as above) and added sub-stoichiometric amounts of EF-G and measured the rate of translocation indirectly by following peptidyl transferase activity. While actual translocation may not be rate-limiting in this system, we reasoned that a large defect in EF-G-catalyzed translocation in ribosomes lacking S13 might be observable under these conditions. However, we found that the rate of translocation in this system was the same, within error, for wild-type and S13-deficient ribosomes (data not shown). In a second approach, we used another single-turnover reaction that follows sparsomycin-catalyzed translocation.28 Because the rate of this EF-G-independent reaction is three to four orders of magnitude slower than EF-G-catalyzed translocation, the rate of the translocation event can be monitored directly in a toeprinting reaction. Again, however, the rates of sparsomycin-catalyzed translocation for wild-type and S13-deficient ribosomes were found to be indistinguishable, and averaged 0.01 s−1. From the results of these experiments, we would argue that while S13 is involved in the maintenance of the pre-translocation state, translocation itself proceeds without a significant contribution from S13.

Mutagenesis studies to identify critical regions of S13

There are several parts of S13 that are situated to play an important structural or regulatory role in the ribosome. As detailed earlier, the N terminus of S13 contacts the C terminus of L5 to form bridge 1b of the ribosome, the body of S13 contacts H38 of the 23 S rRNA to form bridge 1a and the C terminus contacts the P-site tRNA directly. To address the in vivo role of these particular regions of the protein, we constructed a series of point mutations and of C-terminal truncation mutations in S13. In order to simplify the construction of these variant strains, we chose to introduce the various mutant S13 constructs using a plasmid swap approach in the strain carrying a chromosomal deletion of S13 (described above). The starting strain was MG1655, which carries a recA deletion to reduce the likelihood of recombination between wild-type and mutant versions of the S13 gene. In the MG1655 recA− genetic background, S13 appeared to be essential for growth; without expressing an extra-chromosomal copy of S13, there was no colony formation even after prolonged incubation.

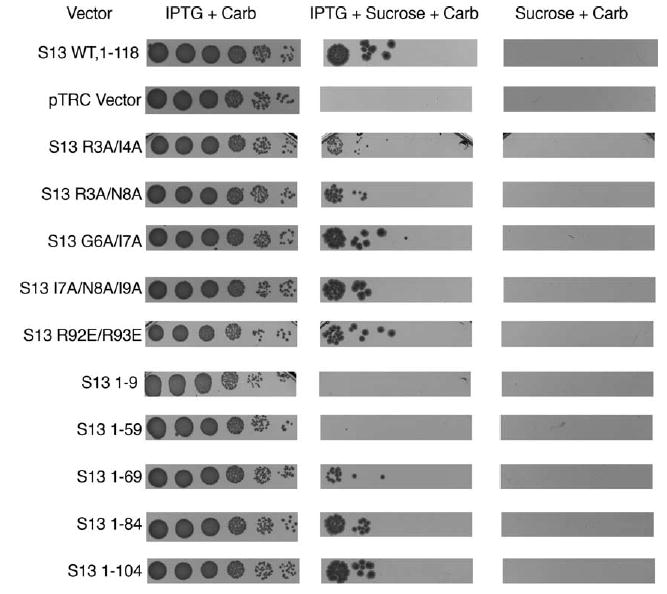

Plasmid swapping in E. coli is accomplished readily using the counter-selectable marker sacB, which renders cells carrying the gene sensitive to sucrose.29 MG1655 recA−cells carrying a plasmid with the wild-type rpsM gene (under its native promoter) and kanR and sacB markers were transformed with the rpsM mutant constructs under the control of an IPTG-inducible promoter and carrying a distinct antibiotic marker, ampR. None of the variant rpsM plasmids yielded a dominant phenotype that was manifested in the presence of the wild-type rpsM vector. Following transformation, the wild-type plasmid was selected against by replating cells on sucrose-containing medium; the absence of wild-type vector was confirmed by kanamycin-sensitivity and IPTG-dependence (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Allelic exchange of mutant plasmid encoded rpsM by selecting against a wild-type rpsM-plasmid with a sacB marker. MG 1655 ΔrpsM ΔrecA cultures containing both a counter-selectable, wild-type rpsM plasmid with a native (non-IPTG-dependent) promoter (S13KSacB) and a mutant rpsM plasmid (IPTG-dependent) conferring carbenicillin resistance were grown to saturation in the presence of carbenicillin. These cultures were diluted 10−1 to 10−6 and replica plated onto media containing: (a) IPTG and carbeni-cillin to look for dominant effects of the mutant plasmid; (b) sucrose, IPTG and carbenicillin to select against the wild-type plasmid and leave the mutant plasmid supporting growth of the cell; (c) sucrose and carbenicillin to demonstrate that growth is IPTG-dependent. Growth of (a) was overnight while (b) and (c) were incubated for two days.

Using this approach, numerous rpsM variant constructs including N-terminal mutations (bridge 1b), mid-protein mutations (bridge 1a) and a series of truncation mutants (P-site tRNA contacts) were obtained that display a range of growth-rate defects when expressed in the absence of wild-type rpsM (Figure 5, Table 2). Mutations that changed N-terminal residues 3 and 4 to alanine (S13:R3A/I4A) (bridge 1b) had a substantial growth defect, as evidenced by reduced colony size on plating as well as slow growth-rates in liquid media. By contrast, mutations incorporated in the region around bridge 1a (residues 92–94, S13 R92E/R93E) had little effect on growth. A series of C-terminal truncation mutations of the 118 amino acid residue protein indicated that the region of S13 that contacts the P-site tRNA directly (S13:1–104) could be removed, but that deletion of the C terminus through bridge 1a to residue 70 still yields viable growth (S13:1–69, S13:1–84, S13:1–104). These data suggest that the N terminus and globular region of the protein (including bridge 1b) play a critical functional or structural role in the ribosome and, conversely, that bridge 1a is less central to function.

Table 2.

The growth rates of the parental strain (MG 1655 ΔrecA), the rpsM knockout with a plasmid encoded rpsM gene, and the rpsM knockout with plasmid encoded rpsM variants in rich LB medium with 200 mM IPTG

| Strain | Plasmid | Doubling time (minutes) |

|---|---|---|

| MG1655 ΔrecA | 32 | |

| MG 1655 ΔrpsM::kan ΔrecA | pTRC S13 wt, 1–118 | 39 |

| MG 1655 ΔrpsM::kan ΔrecA | pTRC S13 R3A/I4A | 92 |

| MG 1655 ΔrpsM::kan ΔrecA | pTRC S13 R3A/N8A | 63 |

| MG 1655 ΔrpsM::kan ΔrecA | pTRC S13 I7A/N8A/I9A | 35 |

| MG 1655 ΔrpsM::kan ΔrecA | pTRC S13 R92E R93E | 40 |

| MG 1655 ΔrpsM::kan ΔrecA | pTRC S13 1–69 | 77 |

| MG 1655 ΔrpsM::kan ΔrecA | pTRC S13 1–84 | 45 |

| MG 1655 ΔrpsM::kan ΔrecA | pTRC S13 1–104 | 40 |

These rates were calculated from a representative single experiment.

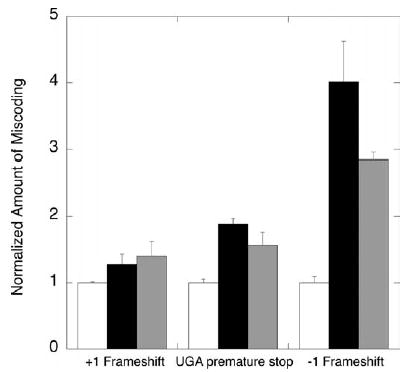

β-Galactosidase assays of S13 variants reveal increased frameshifting and miscoding frequencies

To further characterize S13 variant ribosomes in vivo, we examined the extent of nonsense codon read-through and frameshifting exhibited by S13 variants that displayed substantial growth defects. To perform these experiments, we recreated the genomic rpsM deletion in a ΔrecA ΔlacZ strain, MC150, and then transformed the slow-growing C-terminal truncation variant S13:1–69 and the S13 bridge 1b variant S13:R3A/I4A into this strain. We measured the β-galactosidase expression levels of these S13 variant strains transformed with plasmids encoding constitutively expressed β-galactosidase containing either N-terminal frameshifts or premature stop codons.30 The S13 truncation mutant (S13:1–69) and the bridge 1b variant (S13:R3A/I4A) ribosomes display substantial increases in −1 frameshifting (2.5–4-fold) and stop codon readthrough (1.5–2-fold) when compared to wild-type ribosomes (Figure 6). A more modest increase (1.3–1.4 fold) in +1 frameshifting is observed in the same variant ribosome backgrounds.

Figure 6.

Nonsense suppression and frameshifting in β-galactosidase expression by rpsM variants. Plasmid-encoded wild-type rpsM (white), rpsM R2A/I3A (black), and rpsM 1-69 (grey) were transformed into strain MC150 (ΔrpsM::kan ΔrecA ΔlacZ). The rpsM variants of this strain were then transformed with pSG plasmids encoding constitutively expressed β-galactosidase with N-terminal frameshift or nonsense codons. The β-galactosidase activity of these strains was measured during logarithmic growth.

Discussion

Ribosomal protein S13 is located in the head region of the small subunit, where it makes multiple contacts with the large subunit across the subunit interface and forms direct contacts with the P-site tRNA anticodon region (Figure 7).1 To probe the role of these specific interactions, we have constructed a genomic deletion in E. coli that completely eliminates the open reading frame of the rpsM gene encoding S13. Previous S13 variants generated by more classical genetic approaches and reported as rpsM nulls31 are generally thought to be undefined truncation mutants that display anomalous migration by 2-D gel analysis of the ribosomal proteins.32 Recent advances in gene-knockout technology in E. coli make it relatively straightforward to generate both S13-deletion constructs as well as variant S13 derivatives for defined in vivo and in vitro characterization.19,33 These constructs are of particular value, since the physical heterogeneity and biochemical deficiencies of in vitro reconstituted ribosomes22 have previously placed critical limitations on our ability to bio-chemically characterize ribosomal variants of interest.11

Figure 7.

Location of protein S13 in the ribosome. (a) Schematic describing the interactions that ribosomal protein S13 makes with both large subunit and tRNA elements. Those contacts that are supported by structural analysis are indicated with a star;1 C-terminal residues of S13 contact the P-site tRNA anticodon region, helix 38 of 23 S rRNA contacts S13 and the A-site tRNA elbow through bridge 1a and large ribosomal subunit protein L5 connects S13 to the P-site tRNA elbow region through bridge 1b. (b) Interface view of the 30 S subunit taken from the 70 S structure,1 showing the position of S13 (green) relative to tRNAs and bridges. Note the location of the N-terminal residues comprising bridge 1b (lavender), bridge 1a (cyan), and the C-terminal residues contacting the P-site tRNA (pink).

Interestingly, S13-deficient strains of E. coli were viable, albeit very slow growing, in certain genetic backgrounds. In a recA+ background, the rpsM-deficient cells exhibited a doubling time of 130 minutes relative to the wild-type time of 25 minutes. By contrast, in the less robust recA− genetic background, S13-deficient cells were not demonstrably viable even after extended periods of growth on plates at 37 °C. In this background, however, we were able to mutate key residues and to look at the ability of the mutant S13 to complement the strain as assessed by its growth-rate in the absence of wild-type S13. We found that mutations in the N terminus of S13 (the residues comprising bridge 1b) had profound effects on growth of the cell (doubling time of 92 minutes versus 39 minutes for the wild-type), while changes in bridge 1a had no discernible effect (doubling time of 40 minutes). Analysis of S13 truncation variants indicated that a loss of ten residues in the C terminus of S13, seen in X-ray structures to interact directly with the P-site tRNA,1 had little phenotypic consequence. Indeed, S13 could be C-terminally truncated in this genetic background to leave only 70 amino acid residues (abolishing the P-site tRNA contacts and bridge 1a) and still permit viability. These results are consistent with a recent study characterizing C-terminal truncations in S13.34 Overall, the in vivo data characterizing the growth of rpsM variant strains provide a qualitative feel for the relative importance of the specific interactions made by S13 with the surrounding ribosome, and suggest that its most critical role is in the specific contacts made with the large subunit via bridge 1b.

We also defined a number of biochemical parameters in vitro using exclusively the S13-deficient ribosomes. While the S13-variant ribosomes might have displayed interesting intermediate defects, the potential complications of unequal loss of variant S13 prior to or during the purification procedures (data not shown) convinced us to characterize only the biochemically homogeneous S13-deficient ribosomes in vitro. The overriding theme that emerges from these experiments is that S13-deficient 30 S subunit particles are severely compromised in their subunit association properties. First, polysome analysis of the in vivo ribosome distribution identifies a substantial defect both in the number of polysomes and in the extent of 70 S complex formation in an S13-deficient strain (Figure 2). Thus, while subunit association in this strain is apparently sufficient to confer slow growth, the defects are striking. Second, in vitro subunit association assays provide clear evidence for subunit association defects and we were further able to demonstrate that the defects can be compensated partially with the addition of the mRNA and tRNA substrates of translation that span and stabilize the subunit interface region (Figure 1). Finally, in an assay that is commonly used to measure the rate of assembly of initiation complex,18 we observe substantial defects associated with the S13-deficient ribosomes (Figure 3(a) and (b)).

Structural and biochemical studies have provided clear evidence that subunit association involves a number of discrete molecular interactions.1,3,4,8 Fine-tuning of these multiple interactions must ultimately determine the strength of subunit association and the rate at which subunit joining takes place in the in vivo milieu. In addition to the intrinsic ribosomal features, bound mRNA and tRNA substrates can affect the subunit association dramatically, as can a host of extraribosomal protein factors. For example, the presence of the initiation factor IF3 is sufficient to completely block subunit joining, whereas IF2 acts to promote this event.18 Protein Y (pY)35 binds to the 30 S subunit interface in vitro and has been proposed to play a role in modulating intersubunit interactions. Similarly, RimM and RbfA are proteins that are highly expressed during cold shock (when the ribosomal subunits are dissociated) and associate with the 30 S subunit interface, and their absence yields a polysome profile similar to that observed in our S13-deficient cells.36,37 Our data provide clear evidence that the interactions made by S13 with the large ribosomal subunit play an important role in defining the biologically critical subunit–subunit equilibrium in the ribosome.

To extend our previous work indicating that S12 and S13 play a critical role in stabilizing the pre-translocation state of the ribosome,11 we subjected the S13-deficient ribosomes to a series of translocation assays. Though the effects were relatively modest when, for example, compared with pCMB-modified ribosomal particles,26 the S13-deficient ribosomes displayed increased levels of factor-independent translation in polyphenylalanine synthesis as well as in single-turnover reactions (Figure 4(a) and (b)). Defects in ribosomal components that lead to weakened subunit interactions may generally result in loss of control over tRNA movement through the ribosome. Our efforts here to identify defects in EF-G-promoted translocation were unsuccessful, though pre-steady state kinetic approaches are more likely to reveal such specific defects.38,39

In vivo β-galactosidase reporter assays revealed significant increases in nonsense suppression and frameshifting by several S13-variant containing ribosomes. Both the bridge 1b and the C-terminal truncation mutants of S13 had modest effects on the rates of stop codon readthrough (1.5–2-fold) and substantially increased the rates of −1 frameshifting (2.5–4-fold). The rates of +1 frameshifting were less affected (1.4-fold) by these specific S13 variants, raising the possibility that different molecular mechanisms might need to be invoked to rationalize these distinct frameshifting events.

It should be noted that increases in nonsense suppression and frameshifting often are shared properties of ribosomal variants while missense suppression is less generally observed. Mutations in both 16 S and 23 S rRNA and in the CCA-end of tRNAVal have been isolated that result in substantial increases in the rates of both nonsense suppression and frameshifting (+1 and −1). Interestingly, the mutations in 23 S rRNA are located in domain V of 23 S rRNA in the region where the CCA-ends of the tRNAs bind and function, thus potentially unifying some of these seemingly disparate results.30,40–42 More recently, it has been shown that both chloramphenicol and linezolid antibiotics, which both are thought to bind in the peptidyl transferase center of the large subunit, increase the rates of nonsense suppression and frameshifting dramatically (by 10–20-fold).43 A convincing molecular explanation that unifies these diverse routes for stimulation of nonsense suppression and frame-shifting has not emerged. Though the rate of translation and ribosomal pausing may play a role in frameshifting,44 the consistency of effects originating from the large subunit active site on these events provides an important clue that signaling between the large and small subunits must play a critical role in maintaining the fidelity of translation.

In this study, we were particularly interested in the possibility that S13 might function to relay signals from tRNA bound in the small subunit P site to the interface with the large subunit and beyond. The translational fidelity defects that we observe are consistent with the idea that contacts made by S13 both within the small subunit and across the subunit interface (with protein L5 and helix 38 of the 23 S rRNA) are important for optimal performance in translation. Most exciting is the possibility that the effects of S13 modification result in defects in signal transmission into the core of the large subunit, where L5 and helix 38 of 23 S rRNA directly contact the P-site and A-site tRNAs, respectively (Figure 7).

In light of the substantial movement in S13 that has been documented by cryoEM studies,10 it will be of particular interest to understand the dynamic motions of S13 within the ribosome structure throughout the translation cycle. The system for mutational analysis of S13 and the biochemical defects defined here provide a starting point for future, more detailed dissection of the conformational motions of the ribosome and the role played by S13 in these events.

Materials and Methods

Media, chemicals and other reagents

LB medium was supplemented with 50 mg/l of kanamycin,100 mg/l of carbenicillin, 60 mg/l of spectinomycin, 15 mg/l of tetracycline, 200–500 μmol of IPTG and 10% (w/v) sucrose where appropriate.

Plasmids

The open reading frame (ORF) of the rpsM gene was cloned into the NcoI and BamHI sites of pTRC99b45 to yield pTRCS13. This same S13 product was cloned into a pTRC99b variant with a gene conferring spectinomycin resistance20 to yield pTRCS13-Spec. Mutagenesis of the pTRCS13 plasmid was performed using the QuickChange method (Stratagene). To incorporate a counter-selectable plasmid, S13 with its native promoter was PCR amplified from genomic DNA (MRE600) and cloned into pTRC99b using XbaI and KpnI restriction sites. The lacIq gene and trc promoter were removed from the plasmid by digestion with EcoRV and NcoI, and removal of the fragment; this plasmid was termed S13NPTRC. Finally, the β-lactamase gene was removed and the kan-sacB cassette from plasmid pBip329 was inserted into the vector to yield pS13KSacB. pS13NPTRC was mutagenized with the QuickChange method (Stratagene) to incorporate relevant changes for analysis of miscoding levels.

RpsM gene replacement

The rpsM gene of strain BW25141 containing pKD46 and pTRCS13-Spec plasmids was disrupted by insertion of a kanamycin cassette. This kanamycin cassette was produced by PCR of the pKD4 vector with the primers S13koP1 (5′-GAGTATCCTGAAAAC GGGCTTTTCAG CATG GAACGTACATATTAA ATAGTTGTGTAGGCT GGAGCTGCTTC-3′) and S13koP2 (5′-AGAGACTTGT TTTCTTACACGTTTACGTGCACGAATTGGTGCCTTT TGCCATATGAATATC CTCCTTA-3′) as described19 to yield the strain S13ko51B. In order to derive cells that contained neither genomic nor plasmid copies of the rpsM gene, a generalized P1 transduction experiment was performed using strain S13ko51B as the donor and the MG1655 wild-type strain as the recipient and selection on kanamycin containing plates as described46 to yield S13MG1. The resulting colonies were screened for placement and orientation of the kanamycin cassette using PCR and Southern blot analysis (data not shown).

Cotransduction experiments

Generalized P1 transduction of the tetracycline marker of CAG12075 (donor) strain47 into S13ko51B (recipient strain) and selection of colonies on LB plates containing tetracycline, kanamycin and IPTG was performed as described.46 The resulting P1 lysate of this tetracycline and kanamycin-resistant and IPTG-dependent strain was then used as donor for transduction into MG1655 wild-type cells either complemented or uncomplemented with pTRCS13. Selection was performed on LB plates containing tetracycline and IPTG and after two days growth (pTRCS13 MG1655 cells) or seven days growth (MG1655 wild-type cells), tetracycline-resistant cells were patched onto kanamycin-containing plates and the number of cotranductants was evaluated.

Subunit association

The 30 S subunits from either MG1655 wild-type or S13MG1 were incubated with a sixfold excess of recombinantly purified S13 or buffer and incubated at 42 °C for one hour in reconstitution buffer.22 These 30 S subunits were added to an equimolar quantity of 50 S subunits isolated from MRE600 cells in buffer A (50 mM Tris–HCl (7.5), 70 mM NH4Cl, 30 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2) to a final concentration of 0.25 μM for each subunit and incubated at 37 °C for one hour. This reaction mixture was loaded onto a 10%–40% (w/v) sucrose gradient prepared in SW41 ultracentrifuge tubes and centrifuged for 15 hours at 25,000 rpm in a SW41 rotor. To examine the role of tRNA and mRNA in subunit formation, a post-translocation complex was assembled as follows: 30 S subunits from either MG1655 WT or S13MG1 were combined with a stoichiometric quantity of 50 S subunits isolated from MRE600 cells, gene 32 mRNA, and deacylated fMet tRNA.26 Following incubation for ten minutes at 37 °C in buffer A, N-Ac-Phe-tRNAPhe was added to the complexes and incubated at 37 °C for one hour. As a control, the incubation was repeated in the absence of mRNA and tRNA. These reactions were analyzed by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation as described above.

Polysome profiles

Polysomes of MG1655WT, S13MG1 and S13MG1 transformed with pTRCS13-Spec were prepared as described.48

fMet-puromycin reaction

The following two complexes were assembled independently. Complex I: 1 μM 30 S subunits from MG1655WT or S13MG1 incubated with 3 μM IF1, IF2 and IF3, 0.8 μM f – [35S] – Met – tRNAf Met, 1 mM GTP and 5 μM gene 32 mRNA at 37 °C in buffer B (50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 70 mM NH4Cl, 30 mM KCl, 0.5 mM spermidine, 8 mM putrescine, 2 mM DTT) with either 3.5 mM or 7 mM MgCl2. Complex II: 1 μM 50 S subunits and 4 mM puromycin in buffer B. Complex I and complex II were incubated at 37 °C for ten minutes, mixed, and the reaction was quenched in 0.4 M KOH at various time-points (15 seconds to 15 minutes) and the rate of fMet-puromycin production was observed by TLC as described.23

Polyphenylalanine synthesis assay

Tight-couple 70 S ribosomes from MG1655WT and S13MG1 were prepared and used to perform the poly(U)-based polyphenylalanine synthesis assay as described.26

Single-turnover N-Ac-Phe-Pm formation assay

Tight-coupled 70 S ribosomes from MG1655WT and S13MG1 were used to perform the single turnover N-Ac-Phe-Pm translocation assay as described.26

EF-G-mediated-translocation

Complex I

Tight-coupled 70 S ribosomes purified from 1 μM MG1655WT or 1 μM S13MG1 were incubated with 3 μM IF1, IF2 and IF3, 0.8 μM f-[35S]Met tRNAf Met, 1 mM GTP and 5 μM gene 32 derivative mRNA specifying MFF in buffer A at 37 °C for 30 minutes.

Complex II

A mixture of 6 μM EF-Tu, 6 μM Phe-tRNAPhe, 0.06 μM limiting EF-G, 4 mM phosphoenolpyruvate and 0.4 μg/μl of pyruvate kinase were incubated in buffer A at 37 °C for five minutes. These two complexes were then mixed together and the reaction was quenched in 0.4 M KOH at various time-points (from 15 seconds to 15 minutes) and the rate of tripeptide production was followed by TLC as described.23

Sparsomycin-mediated translocation

Subunits of MG1655WT and S13MG1 were used to perform the sparsomycin assay as described.28

RpsM allelic exchange

A P1 lysate of strain S13ko51B was used to transduce the S13::kanamycin marker into MG1655 ΔrecA with a pSC101 temperature-sensitive recA-containing plasmid and pTRCS13-Spec plasmid. The recA-containing plasmid was selected against by plating at high temperature and the kanamycin marker was removed as described19 to yield an MG1655 ΔrecA ΔrpsM strain called S13MGΔRecA. The resulting strain was transformed with pS13KSacB and outgrown in kanamycin and no IPTG. Cells were screened for loss of the pTRCS13-Spec plasmid and this loss was confirmed by assessing sensitivity to spectinomycin. To perform allelic exchange, this S13MGΔRecA strain with pS13KSacB was transformed with various pS13NPTRC variants and selected on carbenicillin. The resulting cells were grown overnight in carbenicillin and serially diluted and then these dilutions were plated onto LB with carbenicillin, sucrose, and IPTG.

LacZ assays

MC150 is a ΔrecA ΔlacZ strain in which we constructed an MC150 ΔrecA ΔlacZ ΔrpsM pS13KsacB as described above with pS13NPTRC and various pS13NPTRC mutants. The resulting cells were then transformed with pSG lacZ mutants and selected on tetracycline medium. Plasmid pSG Lac7 was used for +1 frameshifting, pSG 3/4 construct was used for UGA premature stop and pSG 12 DP-1 was used for −1 frameshifting.30 β-Galactosidase expression assays were performed as described.30

Growth curves

Growth curves were performed by diluting saturated cultures 1:500 (v/v) into 100 ml of pre-warmed (37 °C) LB cultures and by measuring the absorbance at 600 nm every 40 minutes. The resulting data were fit to an exponential curve (y=A ebx), and a doubling time was calculated as ln(2)/b.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Kramer for advice in developing the knock-out technology targeting the ribosomal proteins, M. O’Connor for advice and sharing of the nonsense suppression and frameshifting β-galactosidase expression system, F. W. Outten and S. Quann for helpful discussions on bacterial genetics. We thank L. Cochella, J. Lorsch, C. Merryman and E. Youngman for careful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by funding from the NIH (R01GM059425-02). R.G. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Edited by J. Doudna

References

- 1.Yusupov MM, Yusupova GZ, Baucom A, Lieberman K, Earnest TN, Cate JH, Noller HF. Crystal structure of the ribosome at 5.5 Å resolution. Science. 2001;292:883–896. doi: 10.1126/science.1060089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moazed D, Noller HF. Intermediate states in the movement of transfer RNA in the ribosome. Nature. 1989;342:142–148. doi: 10.1038/342142a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merryman C, Moazed D, Daubresse G, Noller HF. Nucleotides in 23 S rRNA protected by the association of 30 S and 50 S ribosomal subunits. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:107–113. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merryman C, Moazed D, McWhirter J, Noller HF. Nucleotides in 16 S rRNA protected by the association of 30 S and 50 S ribosomal subunits. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:97–105. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wimberly BT, Brodersen DE, Clemons WM, Jr, Morgan-Warren RJ, Carter AP, Vonrhein C, et al. Structure of the 30 S ribosomal subunit. Nature. 2000;407:327–339. doi: 10.1038/35030006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frank J, Verschoor A, Li Y, Zhu J, Lata RK, Radermacher M, et al. A model of the translational apparatus based on a three-dimensional reconstruction of the Escherichia coli ribosome. Biochem Cell Biol. 1995;73:757–765. doi: 10.1139/o95-084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lata KR, Agrawal RK, Penczek P, Grassucci R, Zhu J, Frank J. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the Escherichia coli 30 S ribosomal subunit in ice. J Mol Biol. 1996;262:43–52. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabashvili IS, Agrawal RK, Spahn CM, Grassucci RA, Svergun DI, Frank J, Penczek P. Solution structure of the E. coli 70S ribosome at 11.5 Å resolution. Cell. 2000;100:537–549. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80690-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank J, Agrawal RK. A ratchet-like inter-subunit reorganization of the ribosome during translocation. Nature. 2000;406:318–322. doi: 10.1038/35018597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao H, Sengupta J, Valle M, Korostelev A, Eswar N, Stagg SM, et al. Study of the structural dynamics of the E. coli 70 S ribosome using real-space refinement. Cell. 2003;113:789–801. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00427-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cukras AR, Southworth DR, Brunelle JL, Culver GM, Green R. Ribosomal proteins S12 and S13 function as control elements for translocation of the mRNA:tRNA complex. Mol Cell. 2003;12:321–328. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dallas A, Noller HF. Interaction of translation initiation factor 3 with the 30 S ribosomal subunit. Mol Cell. 2001;8:855–864. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00356-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCutcheon JP, Agrawal RK, Philips SM, Grassucci RA, Gerchman SE, Clemons WM, Jr, et al. Location of translational initiation factor IF3 on the small ribosomal subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4301–4306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pioletti M, Schlunzen F, Harms J, Zarivach R, Gluhmann M, Avila H, et al. Crystal structures of complexes of the small ribosomal subunit with tetracycline, edeine and IF3. EMBO J. 2001;20:1829–1839. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karimi R, Pavlov MY, Buckingham RH, Ehrenberg M. Novel roles for classical factors at the interface between translation termination and initiation. Mol Cell. 1999;3:601–609. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80353-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter AP, Clemons WM, Jr, Brodersen DE, Morgan-Warren RJ, Hartsch T, Wimberly BT, Ramakrishnan V. Crystal structure of an initiation factor bound to the 30 S ribosomal subunit. Science. 2001;291:498–501. doi: 10.1126/science.1057766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomsic J, Vitali LA, Daviter T, Savelsbergh A, Spurio R, Striebeck P, et al. Late events of translation initiation in bacteria: a kinetic analysis. EMBO J. 2000;19:2127–2136. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.9.2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antoun A, Pavlov MY, Andersson K, Tenson T, Ehrenberg M. The roles of initiation factor 2 and guanosine triphosphate in initiation of protein synthesis. EMBO J. 2003;22:5593–5601. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kramer G, Rauch T, Rist W, Vorderwulbecke S, Patzelt H, Schulze-Specking A, et al. L23 protein functions as a chaperone docking site on the ribosome. Nature. 2002;419:171–174. doi: 10.1038/nature01047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nichols BP, Shafiq O, Meiners V. Sequence analysis of Tn10 insertion sites in a collection of Escherichia coli strains used for genetic mapping and strain construction. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6408–6411. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6408-6411.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Culver GM, Noller HF. Efficient reconstitution of functional Escherichia coli 30 S ribosomal subunits from a complete set of recombinant small subunit ribosomal proteins. RNA. 1999;5:832–843. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Youngman EM, Brunelle JL, Kochaniak AB, Green R. The active site of the ribosome is composed of two layers of conserved nucleotides with distinct roles in peptide bond formation and peptide release. Cell. 2004;117:589–599. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00411-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gromadski KB, Rodnina MV. Kinetic determinants of high-fidelity tRNA discrimination on the ribosome. Mol Cell. 2004;13:191–200. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katunin VI, Muth GW, Strobel SA, Wintermeyer W, Rodnina MV. Important contribution to catalysis of peptide bond formation by a single ionizing group within the ribosome. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Southworth DR, Brunelle JL, Green R. EFG-independent translocation of the mRNA:tRNA complex is promoted by modification of the ribosome with thiol-specific reagents. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:611–623. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma D, Southworth DR, Green R. EF-G-independent reactivity of a pre-translocation state ribosome complex with the aminoacyl tRNA substrate puromycin supports an intermediate (hybrid) state of tRNA binding. RNA. 2004;10:102–113. doi: 10.1261/rna.5148704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fredrick K, Noller HF. Catalysis of ribosomal translocation by sparsomycin. Science. 2003;300:1159–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.1084571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slater S, Maurer R. Simple phagemid-based system for generating allele replacements in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4260–4262. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.4260-4262.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Connor M, Thomas CL, Zimmermann RA, Dahlberg AE. Decoding fidelity at the ribosomal A and P sites: influence of mutations in three different regions of the decoding domain in 16 S rRNA. Nucl Acids Res. 1997;25:1185–1193. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dabbs ER. Mutational alterations in 50 proteins of the Escherichia coli ribosome. Mol Gen Genet. 1978;165:73–78. doi: 10.1007/BF00270378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faxen M, Walles-Granberg A, Isaksson LA. Antisuppression by a mutation in rpsM(S13) giving a shortened ribosomal protein S13. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1218:27–34. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Court DL, Sawitzke JA, Thomason LC. Genetic engineering using homologous recombination. Annu Rev Genet. 2002;36:361–388. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.061102.093104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoang L, Fredrick K, Noller HF. Creating ribosomes with an all-RNA 30 S subunit P site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12439–12443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405227101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agafonov DE, Kolb VA, Nazimov IV, Spirin AS. A protein residing at the subunit interface of the bacterial ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12345–12349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dammel CS, Noller HF. Suppression of a cold-sensitive mutation in 16 S rRNA by over-expression of a novel ribosome-binding factor, RbfA. Genes Dev. 1995;9:626–637. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.5.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lovgren JM, Wikstrom PM. Hybrid protein between ribosomal protein S16 and RimM of Escherichia coli retains the ribosome maturation function of both proteins. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5352–5357. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.18.5352-5357.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Studer SM, Feinberg JS, Joseph S. Rapid kinetic analysis of EF-G-dependent mRNA translocation in the ribosome. J Mol Biol. 2003;327:369–381. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodnina MV, Savelsbergh A, Katunin VI, Wintermeyer W. Hydrolysis of GTP by elongation factor G drives tRNA movement on the ribosome. Nature. 1997;385:37–41. doi: 10.1038/385037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Connor M, Dahlberg AE. Mutations at U2555, a tRNA-protected base in 23 S rRNA, affect translational fidelity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9214–9218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Connor M, Dahlberg AE. The involvement of two distinct regions of 23 S ribosomal RNA in tRNA selection. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:838–847. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Connor M, Willis NM, Bossi L, Gesteland RF, Atkins JF. Functional tRNAs with altered 3′ ends. EMBO J. 1993;12:2559–2566. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05911.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson J, O’Connor M, Mills JA, Dahlberg AE. The protein synthesis inhibitors, oxazo-lidinones and chloramphenicol, cause extensive translational inaccuracy in vivo. J Mol Biol. 2002;322:273–279. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00784-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sipley J, Goldman E. Increased ribosomal accuracy increases a programmed translational frameshift in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2315–2319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amann E, Ochs B, Abel KJ. Tightly regulated tac promoter vectors useful for the expression of unfused and fused proteins in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1988;69:301–315. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90440-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller JH. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1972. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singer M, Baker TA, Schnitzler G, Deischel SM, Goel M, Dove W, et al. A collection of strains containing genetically linked alternating antibiotic resistance elements for genetic mapping of Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:1–24. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.1-24.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Powers T, Noller HF. Dominant lethal mutations in a conserved loop in 16 S rRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1042–1046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.3.1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]