Abstract

The sulfonylurea receptor (SUR), an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) protein, assembles with a potassium channel subunit (Kir6) to form the ATP-sensitive potassium channel (KATP) complex. Although SUR is an important regulator of Kir6, the specific SUR domain that associates with Kir6 is still unknown. All functional ABC proteins contain two transmembrane domains but some, including SUR and MRP1 (multidrug resistance protein 1), contain an extra N-terminal transmembrane domain called TMD0. The functions of any TMD0s are largely unclear. Using Xenopus oocytes to coexpress truncated SUR constructs with Kir6, we demonstrated by immunoprecipitation, single-oocyte chemiluminescence and electrophysiological measurements that the TMD0 of SUR1 strongly associated with Kir6.2 and modulated its trafficking and gating. Two TMD0 mutations, A116P and V187D, previously correlated with persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy, were found to disrupt the association between TMD0 and Kir6.2. These results underscore the importance of TMD0 in KATP channel function, explaining how specific mutations within this domain result in disease, and suggest how an ABC protein has evolved to regulate a potassium channel.

Keywords: ABC transporter/ATP-sensitive K channel/PHHI/sulfonylurea receptor/trafficking

Introduction

The sulfonylurea receptors (SUR1 and SUR2) belong to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) protein superfamily (Ames et al., 1992; Higgins, 1992; Dean and Allikmets, 2001). Mutations in SUR1 lead to persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy (PHHI) (Kane et al., 1996). Normally, high levels of blood glucose cause insulin release by the pancreatic β cells. However, β cells in individuals with PHHI secrete insulin despite low blood glucose levels (Aguilar-Bryan and Bryan, 1999; Miki et al., 1999).

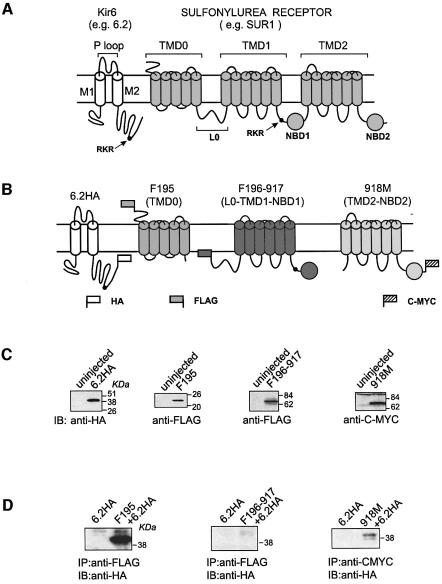

All functional ABC proteins or protein complexes have a similar domain organization, consisting of two transmembrane domains (TMD1 and TMD2) and two nucleotide-binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2) (Figure 1A). A model of how these protein machineries operate has emerged (Ames et al., 1992; Chang and Roth, 2001; Locher et al., 2002). The NBDs catalyze the hydrolysis of ATP, and the resulting free energy is used to drive the transport of substrates across a specific pathway formed by TMD1 and TMD2 (Ames et al., 1992; Chang and Roth, 2001; Locher et al., 2002) or to regulate the gating of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR), the only ABC protein that functions as an ion channel (Gadsby and Nairn, 1999).

Fig. 1. The TMD0 and TMD2–NBD2 segment of SUR1 can physically associate with Kir6.2. (A) Domain organization of the two KATP channel subunits (see Introduction for description). Each subunit has an ER retention sequence motif (RKR), which is represented by a solid circle in the cartoon. (B) Epitope tagging of Kir6 and truncated SUR1 segments. SUR1 is severed into three epitope-tagged segments: F195, F196-917 and 918M. Segment F195 contains TMD0, which comprises amino acids 2–195, tagged at its N-terminus with a FLAG epitope. The last transmembrane segment of TMD0 has been shown to lie before amino acid 195 (Raab-Graham et al., 1999) (Supplementary figure 1). F196-917 contains L0, TMD1 and NBD1, which comprises amino acids 196–917, and is tagged at its N-terminus with FLAG. Amino acid 917 is homologous with the last amino acid of the NBD1 in CFTR defined using a severed approach (Chan et al., 2000) (Supplementary figure 1). 918M contains TMD2 and NBD2, which comprises amino acids 918–1582, and is tagged at its C-terminus with C-MYC. Kir6.2 is tagged with an HA epitope at its C-terminus (6.2HA). (C) Western blots showing the independent expression of 6.2HA, F195, F196-917 and 918M. Membrane extracts from uninjected oocytes were used as the control in each case. (D) Assay of association between Kir6.2 and truncated SUR1 segments by immunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitations were performed, using either anti-FLAG or anti-CMYC antibodies, on digitonin-solubilized membrane extracts of oocytes expressing F195+6.2HA, F196-917+6.2HA and 918M+6.2HA. Anti-HA antibody was used for subsequent western blotting in all cases. Membrane extract from oocytes injected with 6.2HA alone was used as control.

SURs associate with the inwardly rectifying potassium (Kir) channel subunits (Kir6.1 or Kir 6.2) to form the functional KATP channels (Figure 1A) (Clement et al., 1997; Lorenz et al., 1998; Lorenz and Terzic, 1999) and are prevalent in neurons, muscle and pancreatic β cells (Inagaki et al., 1995; Aguilar-Bryan et al., 1998; Seino, 1999). KATP channels are inhibited by intracellular ATP but stimulated by MgADP (Noma, 1983; Dunne and Petersen, 1986; Ashcroft and Gribble, 1998). Therefore, they couple the metabolic state of a cell to its membrane excitability and serve important functions such as insulin secretion, control of vascular tone and protection against ischemia and seizures (Quayle et al., 1997; Miki et al., 1999, 2002; Cohen et al., 2000; Yamada et al., 2001). Kir channels show a characteristic topology of two transmembrane segments (M1 and M2) flanking a pore-forming loop (Doupnik et al., 1995). The N-terminus and M1 of Kir6 are important in the interactions with SURs (Schwappach et al., 2000). The corresponding regions in SURs that interact with Kir6 have yet to be determined.

An endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retention sequence, the RKR motif, is present in each of the Kir6 and SUR subunits of the KATP channel complex (Zerangue et al., 1999). Each subunit expressed alone is retained in the ER. When both subunits are coexpressed, their respective RKR motifs are masked, allowing trafficking of the SUR/Kir6 complex to the cell surface. The RKR motif of Kir6.2 is localized within the last 26 amino acids, deletion of which results in a truncation mutant (6.2Δ26) that, unlike Kir6.2, shows functional expression (Tucker et al., 1997; Zerangue et al., 1999). The last 13 amino acids of SUR1 also contain an anterograde signal which enhances the KATP channel complex to exit the ER (Sharma et al., 1999).

Some ABC proteins, such as MRP1–3, MRP6–7 and SUR, have an additional N-terminal transmembrane domain (TMD0) that is connected to TMD1 by a cytoplasmic loop (L0) (Figure 1A) (Cole and Deeley, 1998; Dean and Allikmets, 2001). Distinct TMD0s from different ABC proteins show different amino acid sequences (Gao et al., 1998) and their functions are largely unclear. The TMD0 in MRP1 seems to be dispensable since its deletion affects neither the transport function nor the cellular targeting of MRP1 (Bakos et al., 1998). The TMD0 of MRP2 is required for correct cellular targeting but is not necessary for transport function (Fernandez et al., 2002). The N-terminal region containing the TMD0 and L0 (TMD0–L0) regions of SUR has been implicated in controlling the gating of the KATP channel (Babenko et al., 1999b).

Here we show that the TMD0 of SUR1 (or simply called TMD0, unless otherwise specified) strongly associates with Kir6.2 and plays an important role in its trafficking and gating. Two TMD0 mutations that are correlated with PHHI were shown to abrogate its association with Kir6.2, underscoring the importance of TMD0 in KATP channel function.

Results

Strong physical association between TMD0 and Kir6.2

We used a deletion approach to identify the molecular determinants in SUR1 responsible for interactions with Kir6.2. Three truncated SUR1 constructs were made: F195, F196-917 and 918M (Figure 1B; see description of these constructs in the legend to Figure 1). We will refer to the extracellular N-terminus and the first five transmembrane segments of SUR1 as its TMD0. An HA tag was added to the C-terminus of Kir6.2 (referred to as 6.2HA). To assay for expression of these channel constructs, cRNA for each construct was injected into Xenopus oocytes and western blotting was performed using antibodies against their tags. As shown in Figure 1C, all four constructs could be detected by their respective antibodies. The predicted molecular weights for 6.2HA, F195, F196-917 and 918M are 44.9, 23.4, 81.9 and 75.6 kDa, respectively. These results indicate that each of these channel constructs can be expressed independently of the others. To determine which of the three SUR1 segments can associate with 6.2, each segment was coexpressed with 6.2HA and immunoprecipitations were performed using the antibodies that recognize the SUR1 segments. A strong band corresponding to 6.2HA could be detected in the precipitate when 6.2HA was coexpressed with F195 (Figure 1D). In contrast, 6.2HA could not be coprecipitated by the FLAG-tagged TMD0 from MRP1 (data not shown). A much weaker 6.2HA protein band was also detected when 6.2HA was coexpressed with 918M. However, 6.2HA could not be coprecipitated by F196-917. These data indicate that there is strong physical interaction between the TMD0 of SUR1 and 6.2. The coprecipitation of a small amount of 6.2HA with 918M suggests the presence of weak interaction between them.

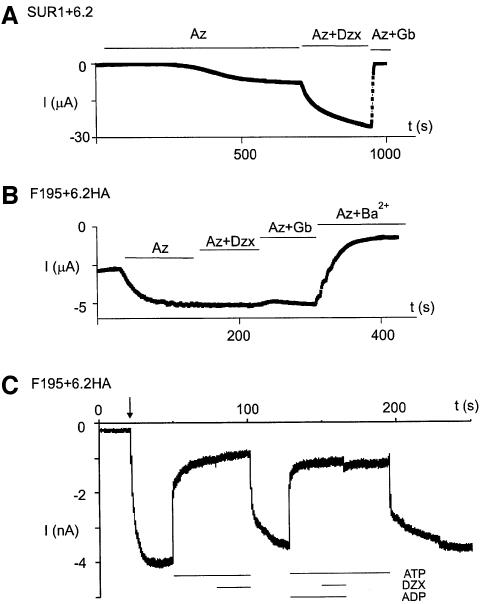

Functional expression of TMD0/6.2HA channels in Xenopus oocytes

If F195 and 918M can associate with 6.2HA, can the resulting complexes form functional channels on the cell surface? To address this question, whole-cell currents from oocytes expressing the SUR1 segment complexes with 6.2HA were measured using two-electrode voltage–clamp (TEVC). Oocytes expressing SUR1+6.2 showed no basal currents (Figure 2A). Sodium azide, a metabolic inhibitor, activated the inwardly rectifying SUR1/6.2 currents reversibly. Washout of sodium azide led to a transient increase in the current, which is caused by the removal of a direct inhibitory effect of sodium azide on the SUR1/6.2 channels (Gribble et al., 1997a; Trapp and Ashcroft, 2000). For uninjected oocytes, no current was activated by sodium azide (Figure 2C). Oocytes expressing F195+6.2HA, unlike the SUR1+6.2 controls, exhibited large basal currents which could be further activated by sodium azide in a reversible manner (Figure 2B). Complete activation and deactivation were about five times faster than those from oocytes expressing SUR1+6.2 (50 s versus 280 s). Both the basal and the azide-stimulated currents from the F195/6.2HA channels showed weak inward rectification (Figure 2B) and the basal current could be blocked by 3 mM BaCl2, a typical Kir-channel blocker. The currents from the 6.2HA channels were not significantly different from those of uninjected oocytes (Figure 2C). The difference in the currents between F195/6.2HA and 6.2HA was not due to an increase in the protein expression level of 6.2HA in the presence of F195 (Figure 2D). Basal and azide-stimulated currents from oocytes injected with F196-917+6.2HA, or 918M+6.2HA or even F196-917+ 918M+6.2HA were similar to those from uninjected oocytes (Figure 2C). Oocytes that were injected with F195+F196-917+918M+6.2HA gave both basal and azide-stimulated currents with activation and deactivation rates similar to those of F195/6.2HA (data not shown). The magnitude of the currents was slightly smaller than that of F195+6.2HA, which may be due to a saturation of the oocyte translational machinery caused by the excessive amount of RNA injected. Nevertheless, it is clear that even coexpressing F196-917 and 918M could not convert F195/6.2HA to an SUR1/6.2 channel. We conclude that F195/6.2HA, but not 918M/6.2HA, forms functional channels with characteristics different from SUR1/6.2 when expressed in oocytes.

Fig. 2. Functional expression of F195/6.2HA channels. (A and B) F195/6.2HA channels display currents that are distinct from those shown by SUR1/6.2 channels. The left panel shows a representative time course of current measured from an oocyte expressing (A) SUR1+6.2 or (B) F195+6.2HA. Current was measured at –80 mV by TEVC. The bath solution contains 96 mM K+, and 3 mM sodium azide or 3 mM BaCl2 was included, as indicated, to cause metabolic inhibition or channel blockade, respectively. The right panels show the I–V relationships obtained at time points t1–t3 as indicated on the time courses shown on the left panels. (C) Histogram of basal and azide-induced currents measured at –80 mV using TEVC. Only the basal currents from oocytes expressing F195+6.2HA or F195+F196-917+918M+6.2HA are shown. The basal currents from other groups of ooyctes are similar to that of uninjected oocytes. Each bar is an average of at least five measurements (n ≥ 5). (All current histograms in subsequent figures represent currents measured at –80 mV.) (D) Western blotting showing that the expression level of 6.2HA protein is not changed by the presence of F195.

Functional disruption of the RKR motif in Kir6 allows functional expression of TMD0/Kir6 complex

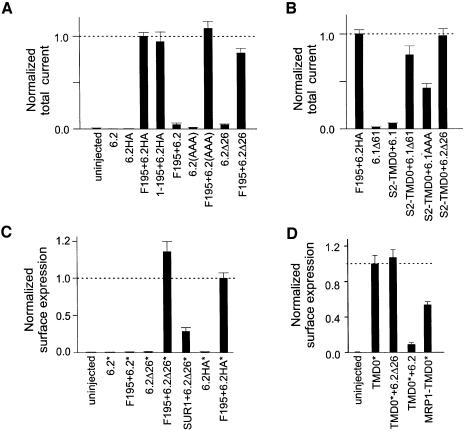

The successful functional expression of F195/6.2HA channels requires the masking of the RKR motif in 6.2. We tested for a possible effect of the C-terminal HA tag on the RKR motif by measuring currents from oocytes expressing F195+6.2 and comparing them with the F195/6.2HA currents (Figure 3A). Total current (basal plus azide-stimulated) from F195+6.2 was greatly reduced compared with that of F195+6.2HA. Removing the FLAG epitope from F195 had no effect on the current expression of F195+6.2HA. Functional disruption of the RKR motif in the F195/6.2 complexes, either by mutating the RKR to AAA (i.e. 6.2AAA) or by deletion (i.e. 6.2Δ26), also led to large current expression. These data suggest that the RKR motif in 6.2 reduces the surface expression of the F195/6.2 complex and the HA tag added to the C-terminus of 6.2 can disrupt the function of its RKR motif. Also, it is clear that TMD0 of SUR1 can enhance the functional expression of all of the 6.2 constructs listed in Figure 3A, particularly those where the function of the RKR motif is disrupted (i.e. 6.2Δ26, 6.2AAA, 6.2HA).

Fig. 3. TMD0 can traffic to the cell surface and enhance the surface expression of RKR-disrupted Kir6. (A) TMD0 of SUR1 can enhance functional expression of RKR-disrupted 6.2. Histogram of total currents (basal + azide-stimulated currents) measured from oocytes expressing different channels normalized to that from oocytes expressing F195+6.2HA (n ≥ 10). (B) TMD0 of SUR2 (S2-TMD0) can enhance functional expression of 6.1Δ61, 6.1AAA and 6.2Δ26 (n ≥ 6). (C) F195 can enhance the surface expression of RKR-disrupted 6.2. An HA tag was added to the first extracellular loop of 6.2, 6.2Δ26 and 6.2HA, and is indicated by an asterisk. Note that 6.2HA* also has a second HA tag at its C-terminus. Surface expression of different 6.2* constructs was assayed by single-oocyte chemiluminescence (n ≥ 10). (D) High surface expression of both SUR1 and MRP1 TMD0. An extracellular HA tag (asterisk) was added to the N-terminus of the TMD0 from SUR1 or MRP1. Surface expression of TMD0* constructs was assayed by single-oocyte chemiluminescence (n ≥ 10) The high surface expression of TMD0* is not affected by the presence of 6.2Δ26 but is decreased by the presence of 6.2.

Since different tissue-specific KATP channels are formed by the combination of specific SUR and Kir6 subunits, we proceeded to test whether an equivalent TMD0–6.2 interaction exists between a different TMD0 and Kir6 subunits. We expressed wild-type Kir6.1 (6.1), RKR disrupted 6.1 (6.1Δ61 and 6.1AAA) and 6.2Δ26 with the TMD0 from SUR2 (S2-TMD0) (Figure 3B). Large total currents were obtained from oocytes expressing S2-TMD0+6.1Δ61, S2-TMD0+6.1AAA and S2-TMD0+ 6.2Δ26. Oocytes expressing 6.1Δ61 alone gave currents similar to those of uninjected oocytes. Therefore, TMD0 from SUR2 can functionally interact with 6.1Δ61, 6.1AAA and 6.2Δ26, and can enhance their current expressions. S2-TMD0+6.1 gave rise to total currents similar to those of uninjected oocytes, presumably due to retention of the S2-TMD0/6.1 complex in the ER.

TMD0 can traffic to the cell surface and enhances the surface expression of 6.2Δ26

How does TMD0 enhance the functional expression of RKR-disrupted Kir6 (e.g. 6.2Δ26)? F195 could cause this effect by increasing the number of 6.2Δ26 channels on the cell surface and/or by increasing the open probability of the 6.2Δ26 channels. To explore the first possibility, an HA epitope was engineered to the first extracellular loop of 6.2, 6.2Δ26 and 6.2HA (Figure 3C). This extracellular HA epitope (denoted by an asterisk in Figure 3C) allows quantitation of Kir6 channels expressed on the cell surface of a single oocyte using chemiluminescence (Zerangue et al., 1999). When 6.2, 6.2Δ26 and 6.2HA were expressed alone, surface signals were low and were only slightly higher than that of the control (uninjected oocyte). Coexpression with F195 resulted in a slight increase in the surface signals for 6.2, but a striking increase in the surface signals for 6.2Δ26 and 6.2HA. The results from the surface detection assay correspond well to the current measurements (Figure 3A), suggesting that TMD0 increases the functional expression of RKR-disrupted Kir6 by mainly increasing the number of channels expressed on the cell membrane. SUR1 could also increase the surface expression of 6.2Δ26, although the surface signal obtained for 6.2Δ26 was ∼30% of that when 6.2Δ26 was coexpressed with F195.

Can TMD0 traffic to the cell surface in the absence of the other parts of the SUR molecule and 6.2Δ26? To investigate this, an HA tag (denoted by an asterisk in Figure 3D) was engineered to the N-terminus of TMD0 and its surface expression was measured. TMD0 could indeed traffic to the plasma membrane, as shown by the large surface signal obtained from oocytes expressing TMD0 (Figure 3D). Coexpressing 6.2, but not 6.2Δ26, caused a large reduction in the surface expression of TMD0, consistent with the trapping of TMD0/6.2 complexes in the ER caused by the RKR motif in 6.2. The surface expression of the TMD0 from another ABC protein, MRP1, was similarly high, indicating that MRP1-TMD0 can also traffic to the cell surface independently of the rest of the MRP1 molecule.

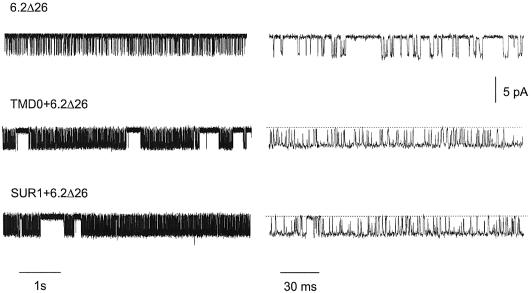

Single channels of SUR1-TMD0/6.2Δ26 and SUR1/6.2Δ26 are indistinguishable in the absence of nucleotides and drug modulators

In order to investigate whether TMD0 affects the gating of 6.2, single channels were recorded from oocyte membrane patches expressing 6.2Δ26, TMD0 + 6.2Δ26 and SUR1 + 6.2Δ26 (Figure 4). Single channels of TMD0/6.2Δ26 and SUR1/6.2Δ26 were very similar and were clearly different from those of 6.2Δ26 in that they displayed longer bursts of activity (Figure 4, left panels). Single-channel current amplitudes were similar in all three cases. The open and closed times, the burst duration and the open probability Po were analysed and their values are listed in Table I. All these parameters were very similar for the TMD0/6.2Δ26 and SUR1/6.2Δ26 channels. Their τo were about twice those of the 6.2Δ26 channels, while the burst durations were ∼25 times those of the 6.2Δ26 channels. The values of τc1 and τc2 were similar for all three channels. The values of Po for the TMD0/6.2Δ26 and SUR1/6.2Δ26 channels were ∼0.6, and were ∼4 times those of 6.2Δ26, which can be explained by the lower frequency of openings and smaller τo for the 6.2Δ26 channels. These data indicate that TMD0 and full-length SUR1 exert equivalent effects on the single-channel behavior of 6.2Δ26 in the absence of nucleotides and drug modulators.

Fig. 4. TMD0/6.2Δ26 and SUR1/6.2Δ26 channels have very similar single-channel properties under nucleotide-free conditions. Single-channel recordings of 6.2Δ26, TMD0/6.2Δ26 and SUR1/6.2Δ26 channels. Two different time scales are shown. Single channels were recorded at –80 mV from inside-out patches with 96 mM K+ on both sides.

Table I. Single-channel parameters for 6.2Δ26, TMD0+6.2Δ26 and SUR1+6.2Δ26.

| Channel |

τo (ms) |

τc1 (ms) |

τc2 (ms) |

Burst duration (ms) |

Po |

| 6.2Δ26 | 0.76 ± 0.04 | 0.44 ± 0.031 | 6.7 ± 1.1 | 2.33 ± 1.2 | 0.15 ± 0.095 |

| TMD0+6.2Δ26 | 1.81 ± 0.03 | 0.48 ± 0.026 | 9.8 ± 3.4 | 52 ± 15 | 0.63 ± 0.086 |

| SUR1+6.2Δ26 | 1.83 ± 0.09 | 0.48 ± 0.021 | 6.3 ± 2.5 | 69 ± 7 | 0.65 ± 0.083 |

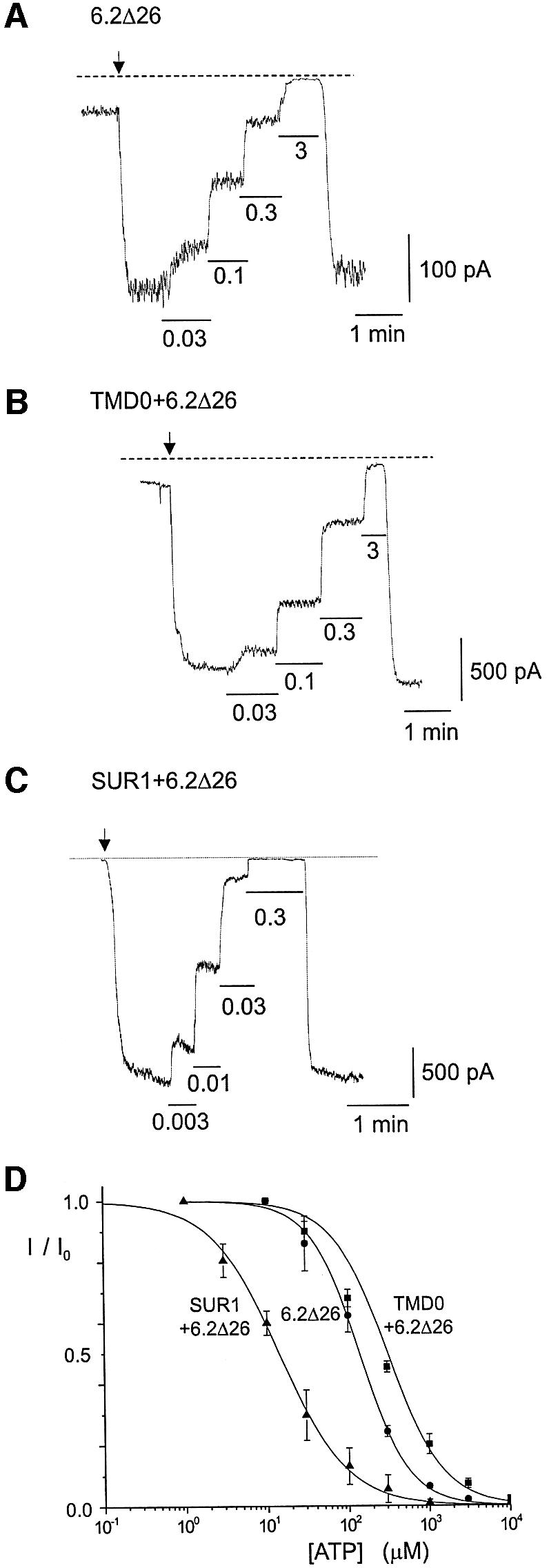

TMD0/6.2Δ26 channels are less sensitive to ATP inhibition and are insensitive to MgADP, glibenclamide and diazoxide

In order to measure the ATP sensitivity of the 6.2Δ26, TMD0/6.2Δ26 and SUR1/6.2Δ26 channels, macropatches were excised from ooyctes expressing each channel type and currents were measured at different concentrations of ATP in the bath (Figure 5A, B and C). Figure 5D compares the dose–response curves for the three channels. The ATP concentration required to cause 50% inhibition (Ki) for TMD0/6.2Δ26 channels was about twice that of 6.2Δ26 and ∼20 times higher than that of SUR1/6.2Δ26. TMD0, unlike full-length SUR1, did not increase the ATP sensitivity of 6.2Δ26.

Fig. 5. ATP sensitivity of SUR1-TMD0/6.2Δ26 channels is similar to that of 6.2Δ26 channels. (A–C) Representative macropatch recordings from oocytes expressing 6.2Δ26, TMD0+6.2Δ26 and SUR1+6.2Δ26. Patch excisions are indicated by arrows. Different concentrations of ATP (in mM) were applied to the inside of the patches as indicated. Both the pipette and bath solutions contain 140 mM K+. The holding potential was –80 mV. (D) Dose–response curves for ATP inhibition. The Ki values (μM)for the 6.2Δ26, TMD0+6.2Δ26 and SUR1+6.2Δ26 channels are 138.4 ± 57.48 (n = 3), 308.92 ± 13.83 (n = 9) and 14.19 ± 1.07 (n = 2), respectively. Their Hill coefficients are 1.45 ± 0.10, 1.27 ± 0.03 and 1.05 ± 0.08, respectively.

The sensitivity of F195/6.2HA channels to diazoxide and glibenclamide was tested (Figure 6A and B). Unlike the SUR1/6.2 channels, F195/6.2HA channels were neither activated by diazoxide nor inhibited by glibenclamide. Currents recorded from inside-out macropatches also showed that F195/6.2HA channels, which have been inhibited by ATP, could not be activated by MgADP (Figure 6C). The lack of sensitivity of the F195/6.2HA channels to diazoxide, glibenclamide and MgADP is expected because of the deletion of critical regions of SUR1 (e.g. NBDs and TMD2), which have been shown to be important for the actions of these channel modulators (Nichols et al., 1996; Gribble et al., 1997b; Shyng et al., 1997; Schwanstecher et al., 1998; Babenko et al., 2000; Moreau et al., 2000; Zingman et al., 2001, 2002).

Fig. 6. SUR1-TMD0/6.2HA channels are insensitive to MgADP, diazoxide and glibenclamide. (A) SUR1/6.2 channels are activated by diazoxide but inhibited by glibenclamide. Representative time course of currents measured from an oocyte expressing SUR1+6.2. Currents were measured at –80 mV by TEVC. Additions of 3 mM azide (Az), 340 μM diazoxide (DZX) and 10 μM glibenclamide were made to the bath solution as indicated. (B) SUR1-TMD0/6.2HA channels are insensitive to diazoxide and glibenclamide. Conditions as in (A) except that the oocyte was expressing F195+6.2HA. (C) SUR1-TMD0/6.2HA channels are insensitive to MgADP. Macropatch recording from oocyte expressing F195+6.2HA. The arrow indicates the time of patch excision (inside-out patch). Applications of 1 mM ATP, 340 μM diazoxide and 1 mM ADP were made to the inside of the patch as indicated.

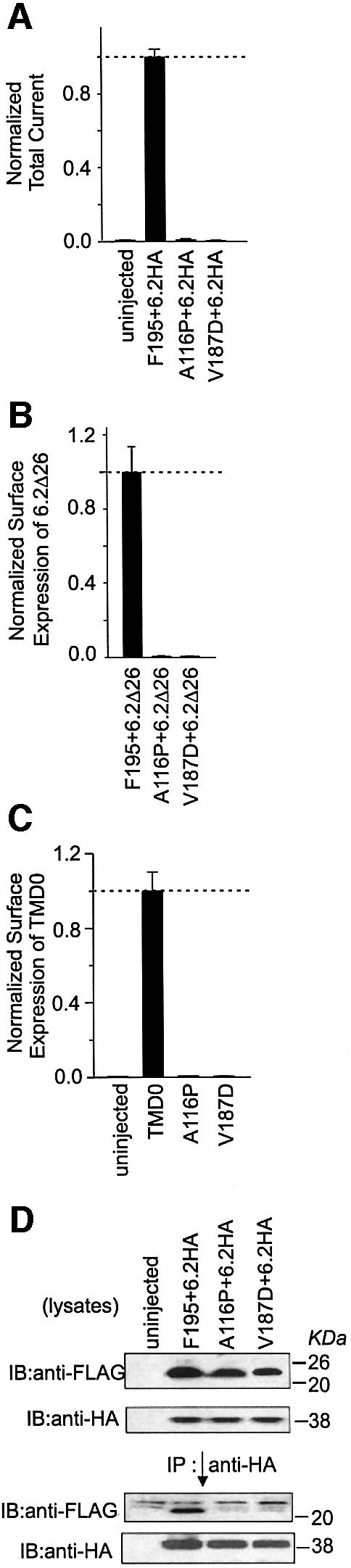

Two PHHI mutations located in TMD0 abolish its association with 6.2

Two TMD0 mutations, A116P and V187D, have been reported to cause PHHI (Aguilar-Bryan and Bryan, 1999; Otonkoski et al., 1999). The effects of these two mutations on the function of TMD0 were assessed. The current exhibited from the F195/6.2HA channels, the ability of F195 to enhance the surface expression of 6.2Δ26 and the ability of F195 to traffic to the cell surface were all abolished by both mutations (Figure 7A, B and C). Although these two mutations do not appear to have a gross effect on the protein expression of F195, immunoprecipitation showed that either mutation completely abolished the association between TMD0 and 6.2HA (Figure 7D).

Fig. 7. Two PHHI mutations located in TMD0, A116P and V187D disrupt the association between TMD0 and 6.2. (A) A116P and V187D mutations completely abolish the total current expressed from TMD0+6.2HA. Total currents were measured from Xenopus oocytes using TEVC and values from the mutated F195+6.2HA channels are normalized to that of the wild-type F195+6.2HA channels. (B) A116P and V187D mutations completely abolish the ability of TMD0 to enhance the surface expression of 6.2Δ26. Surface expression of 6.2Δ26* was measured and values obtained from the mutated F195+6.2Δ26* were normalized to that of the wild-type F195+6.2Δ26*. (C) A116P and V187D mutations completely abolish the ability of TMD0 to traffic to the cell surface. Surface expression of the mutated TMD0* is normalized to that of the wild type. (D) A116P and V187D mutations disrupt the association between TMD0 and 6.2. Total oocyte membranes (lysates) were assayed for expression of 6.2HA and wild-type or mutated-F195 proteins (upper two panels). Anti-HA antibody was used for immunoprecipitations and the precipitated proteins were assayed for the presence of F195 and 6.2HA (lower two panels).

Discussion

The TMD0 of an ABC protein can couple to a potassium channel

Using a deletion approach, we set out to find the structural determinants in SUR1 that are important in its interactions with Kir6.2. Three truncated SUR1 proteins were used for this purpose. The results from F196-917 and 918M need to be interpreted with caution. It is possible that these two proteins are not inserted in the membrane correctly, which would explain why they show weak or no physical association with 6.2HA (Figure 1D). We found that the 918M segment is likely to insert into the membrane with the correct topology (Supplementary figure 2, available at The EMBO Journal Online). Another possibility is that the F196-917 and 918M proteins are misfolded. We have also deleted TMD0 from SUR1. The resulting construct did not show an effect on current expression and was not detected on the cell surface when coexpressed with the other channel segments, highlighting the deleterious effect of truncating TMD0 from SUR1 (Supplementary figure 3). Nevertheless, the inescapable conclusion from our results is that TMD0 interacts with Kir6.2Δ26 and affects its gating and trafficking through strong direct physical association.

TMD0 is only found in certain members of the C subfamily of ABC proteins, including MRP1–3, MRP6–7 and SUR. There is no sequence homology among different TMD0s (Gao et al., 1998). The function of TMD0 in any of these ABC proteins is not clear. Our finding demonstrates unambiguously a direct functional role for the TMD0 of an ABC protein, and raises the interesting possibility that, during evolution, some ABC proteins might have acquired TMD0 as an extra domain to serve a specialized purpose, such as regulating the function of a potassium channel. It is possible that TMD0s of other ABC proteins also associate with membrane proteins and modulate their function.

Two distinct functions of SUR in enhancing the trafficking of Kir6.2 to the cell membrane

The RKR motif present in each of the SUR and Kir6 subunits restricts their individual surface expression. Each RKR motif is masked when the two subunits associate in the correct stoichiometry. This leads to successful trafficking of the KATP channel complex to the cell surface. However, disrupting the RKR motif in Kir6.2 increases its surface expression to a level much lower than that achieved when TMD0 or SUR is present (Figure 3C). Immunostaining of Kir6.2Δ36 in transfected COS7 cells also indicated that the majority of Kir6.2Δ36 proteins were localized in the ER (Ma et al., 2001). Therefore, the RKR-mediated ER retention mechanism is not the only factor determining the trafficking of Kir6.2 to the plasma membrane.

Compared with previous reports (Tucker et al., 1997; Zerangue et al., 1999), we detected relatively smaller whole-cell currents from Kir6.2Δ26 (Figure 3A; Supple mentary figure 4). However, conspicuous currents could clearly be detected from macropatches expressing Kir6.2Δ26 under ATP-free conditions (Figure 5A). One possible explanation is that whole-cell currents are dependent on the metabolic states of the oocytes, which can vary among different laboratories.

TMD0 plays an important role in the trafficking of Kir6.2 since it greatly enhances the surface expression of Kir6.2 following masking or disruption of the RKR motif in Kir6.2. The RKR motif of Kir6.2 must be masked by SUR1 domains other than TMD0, because TMD0 alone cannot override its function. Therefore, SUR1 has two distinct roles in ensuring the high surface expression of Kir6.2: (i) to mask the RKR motif of Kir6.2; (ii) to greatly increase the surface expression of Kir6.2 by a mechanism involving association with TMD0. Because TMD0 can be localized to the plasma membrane efficiently (Figure 3D), we hypothesize that it contains a forward signal that is responsible for its high surface expression and its ability to enhance the surface localization of an associated protein, such as Kir6.2Δ26.

Both the functional and surface expression data indicate that the HA epitope added to the C-terminus of Kir6.2 can disrupt the function of its RKR motif (Figure 3A and C). Fusing a FLAG epitope or green fluorescent protein (GFP) to the C-terminus has a similar effect, whereas a FLAG epitope engineered to the N-terminus does not affect the function of the RKR motif (data not shown). It has been shown that Kir6.2 could be expressed on the cell membrane independent of SUR (John et al., 1998; Makhina and Nichols, 1998). In some of these studies, Kir6.2 was tagged at one of its termini. In light of our findings, epitopes introduced to Kir6.2 at its C-terminus might enhance its surface expression in the absence of SUR.

Effect of TMD0 on the channel properties of Kir6.2Δ26

Besides affecting the trafficking of Kir6.2Δ26, TMD0 also modulates its gating. SUR affects the gating of Kir6.2Δ26 by increasing its burst duration and Po (Babenko et al., 1999a). Our data demonstrated that TMD0/Kir6.2Δ26 and SUR1/Kir6.2Δ26 showed indistinguishable single-channel kinetics (Figure 4), indicating that TMD0 alone is sufficient to confer the characteristic long bursts of activity on Kir6.2Δ26. Using a chimeric approach (Babenko et al., 1999b), the TMD0-L0 region of SUR was implicated as being responsible for this gating effect on Kir6.2. Our data unambiguously assign this gating effect of SUR1 on Kir6.2 to a direct interaction between TMD0 and Kir6.2.

Since TMD0/Kir6.2Δ26 and SUR1/Kir6.2Δ26 show indistinguishable single-channel kinetics, this must also mean that, under nucleotide-free conditions, the other SUR1 domains do not functionally couple to Kir6.2Δ26. However, the other SUR1 domains are required for coupling the effects of MgADP, sulfonylureas and potassium channel openers to the Kir6.2Δ26 subunit because TMD0/6.2Δ26 channels are not sensitive to these pharmacological agents (Figure 6). Whether these SUR1 domains functionally couple to Kir6.2Δ26 directly or indirectly (e.g. through TMD0) remains to be determined.

Since SUR increases the ATP sensitivity of Kir6.2, does TMD0 confer this characteristic on Kir6.2Δ26? Our data indicate that TMD0 does not, because the ATP sensitivity of TMD0/Kir6.2Δ26 is slightly less than that of the Kir6.2Δ26 channels, which can be explained by their higher Po compared with the Kir6.2Δ26 channels (Enkvetchakul et al., 2000). Taken together, these data suggest that TMD0 increases the current expression of Kir6.2Δ26 by decreasing its ATP sensitivity and increasing its surface expression and Po.

PHHI mutations affect KATP channels by disrupting the function of TMD0

Two mutations, A116P and V187D, have been reported to correlate with PHHI (Aguilar-Bryan and Bryan, 1999; Otonkoski et al., 1999). Both are located in the transmembrane segments of TMD0. While detailed analysis of A116P has not been reported, V187D has been shown to abolish the function of the pancreatic KATP channels both in native β cells and when expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Otonkoski et al., 1999). We found that both mutations can greatly impair the function of TMD0 by disrupting its association with Kir6.2. How do these two mutations affect the association between TMD0 and Kir6.2? Because these two mutations abolish the ability of TMD0 to traffic to the cell membrane, it is possible that they cause misfolding in TMD0, resulting in ER retention. Mutations causing cystic fibrosis have been found in the transmembrane segments of CFTR that lead to misfolding of the CFTR protein (Denning et al., 1992; French et al., 1996). These two PHHI-correlated mutations found in TMD0 further underscore the importance of TMD0 in the physiological function of the KATP channel.

Materials and methods

Molecular biology

Constructs were made by either standard PCR or quick-change site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene). FLAG (MDYKDDDDK), C-MYC (EKLISEEDL) and HA (YPYDVPDYA) epitopes were introduced by incorporating their coding sequences into PCR primers. F195, F196-917, 918M and 6.2HA are described in Figure 1. S2-TMD0 contains the first 193 amino acids of SUR2A. MRP1-TMD0 contains the first 195 amino acids of MRP1. The extracellular HA tag was introduced between amino acids P102 and G103 of Kir6.2, and the peptide DLYAYMEKGIT was also inserted between G98 and D99, as described (Zerangue et al., 1999). All constructs were subcloned into pGEMHE (Liman et al., 1992).

Oocyte preparation, western blotting and immunoprecipitation

Oocytes were surgically removed from female Xenopus laevis and were treated with collagenase as described (Chan et al., 2000). All constructs in pGEMHE were linearized by NheI and cRNAs were synthesized using the mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion). Four nanograms of SUR1, 1 ng of TMD0 [including F195, F195(A116P), F195(V187D), TMD0*, 1–195, S2-TMD0 and MRP1-TMD0*], 3 ng of F196-917, 3 ng of 918M and 2 ng of Kir6 (including various 6.2 and 6.1 constructs) RNAs were used in independent or coexpression experiments for TEVC, macropatch recording, western blotting and immunoprecipitation. For single-channel recording, the ratio of TMD0 or SUR1 RNA to 6.2Δ26 RNA was 10:1 and the amount of RNA injected was reduced to ∼0.05–0.1 ng of 6.2Δ26 RNA.

Total oocyte membranes were prepared from 20–40 oocytes. All steps were carried out on ice or at 4°C. Oocytes were homogenized, using a 261/2 gauge needle connected to a 1 ml syringe, in a lysis buffer containing 5 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA and 1× protease inhibitor (Sigma). Homogenate was spun at 3000 g for 10 min and the resulting supernatant was further spun at 200 000 g for 30 min. The pellet containing the membrane fraction was resuspended in the lysis buffer (1 µl/oocyte).

Twenty microliters of membrane proteins were resuspended in 750 µl of an Ip buffer containing 1% digitonin (Calbiochem), 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl and 1× protease inhibitor. This membrane protein suspension was rocked at 4°C for 1 h. Insoluble matter was removed by spinning at 200 000 g for 30 min. The supernatant was used for immunoprecipitation according to the standard protocol (Sambrook et al., 2001). Either the M2-agarose (Sigma) or the anti-HA antibody (Roche) and protein G–Sepharose (Amersham) was used. The precipitants were washed once with Ip buffer and three times with the Ip buffer without digitonin, and eluted with SDS–PAGE sample buffer at 90°C. Membrane proteins or immunoprecipitants were resolved by 12% SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Standard western blotting, using Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and 1% non-fat milk powder, was performed (Sambrook et al., 2001). Anti-M5 (Sigma; 1:500 dilution), anti-HA (Roche; 1:500 dilution) or anti-CMYC (Roche; 1:400 dilution) antibody was used. All washing steps were performed using 0.2% Tween containing TBS. Enhanced ECL reagents (Amersham) were used for detection.

Electrophysiology

TEVC recording was used to measured whole-cell currents from oocytes expressing various channel constructs. ND96 solution (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, 1.8 mM CaCl2 pH 7.5) was used for the bath. Stock solutions of 3 M sodium azide (1000×) and 1 M BaCl2 (333×) were dissolved in water, and 340 mM diazoxide (Sigma; 1000×) and 20 mM glibenclamide (Sigma; 2000×) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Oocyte membrane was held at –80 mV and a ramp from –100 to +100 mV was applied in 1 s. Currents at –80 mV from the ramp were used to plot the time course of the current and for comparing current expression among different channel constructs.

Inside-out macropatch recording was used to measure the response of the current to ATP inhibition. The currents were filtered at 0.2 kHz, sampled at 0.5 kHz and recorded using an EPC9 amplifier (HEKA). The pipette solution was 120 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM HEPES. The bath solution was 120 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA and 10 mM HEPES. Pipette resistance was 0.3–0.7 MΩ. ATP stock solution was dissolved in water and pH was adjusted to 7.2. Because there was little rundown during the experiments, the steady current at a particular ATP concentration was measured and the averages of these were used to plot the ATP dose–response curve. The data were used to fit the Hill equation: I/Ic = 100 × {Kin/(Kin + [ATP]n)}, where I and Ic are the currents measured at the test ATP concentration and no ATP-containing solution, respectively, [ATP] is the ATP concentration used, Ki is the inhibition constant and is equal to the ATP concentration when current inhibition is 50% and n is the Hill coefficient.

Single-channel recording was similar to the inside-out macropatch recording except that the pipette used was much smaller (resistance 5–10 MΩ) and the amount and ratio of RNAs injected were adjusted (see description of oocyte preparation). The bath solution was the same as for the macropatch. Single-channel currents were filtered at 5 kHz and sampled at 10 kHz. The digitized data were analyzed using a combination of TAC (HEKA) and pCLAMP 8 (Axon), helped with in-house software. The open probability of the channel was calculated by dividing the overall open probability in the patch by the number of channels seen opening in the patch. The channel open time can be well fitted with a single-exponential function. Burst duration was analyzed with a burst delimiter determined using pStat and Origin. At least three closed states can be seen in the single-channel data analysis. The shortest one represents the closed state within a burst and the medium one represents the closed state between burst openings; a very long closed state can also be seen between burst openings, which varies significantly from patch to patch. Therefore, we did not include this state in the analysis.

Single-oocyte surface expression assay

Surface expression assay was performed using the single-oocyte chemiluminescence protocol as described (Schwappach et al., 2000). We used 0.35 µg/ml rat monoclonal anti-HA antibody and a 1000× dilution of the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Roche). Individual oocytes were put into 50 µl Power Signal Elisa (Pierce) and incubated for 1 min. Chemiluminescence was quantitated using a Turner 20e luminometer.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at The EMBO Journal Online.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr P.Gros for the HA-tagged human MRP1, Dr J.Bryan for the hamster SUR1 cDNA and Dr S.Seino for the rat SUR2A, mouse Kir6.2 and rat Kir6.1 cDNAs. We are grateful to Dr X.Yan, H.Walsh and B.Liu for preparing the oocytes. We thank M.Szenk for some technical help. We thank Dr B.Schwappach for sharing her protocol and additional advice on the single-oocyte chemiluminescence assay. We are grateful to Dr M. Vivaudou and Dr A.Terzic for critical comments on the manuscript. Furthermore, we thank many of the Logothetis laborarory members for insightful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grant DK60104 to K.W.C. and NIH grant HL59949 to D.E.L.

References

- Aguilar-Bryan L. and Bryan,J. (1999) Molecular biology of adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels. Endocr. Rev., 20, 101–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Bryan L., Clement,J.P., Gonzalez,G., Kunjilwar,K., Babenko,A. and Bryan,J. (1998) Toward understanding the assembly and structure of KATP channels. Physiol. Rev., 78, 227–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames G.F., Mimura,C.S., Holbrook,S.R. and Shyamala,V. (1992) Traffic ATPases: a superfamily of transport proteins operating from Escherichia coli to humans. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol., 65, 1–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft F.M. and Gribble,F.M. (1998) Correlating structure and function in ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Trends. Neurosci., 21, 288–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babenko A.P., Gonzalez,G., Aguilar-Bryan,L. and Bryan,J. (1999a) Sulfonylurea receptors set the maximal open probability, ATP sensitivity and plasma membrane density of KATP channels. FEBS Lett., 445, 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babenko A.P., Gonzalez,G. and Bryan,J. (1999b) Two regions of sulfonylurea receptor specify the spontaneous bursting and ATP inhibition of KATP channel isoforms. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 11587–11592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babenko A.P., Gonzalez,G. and Bryan,J. (2000) Pharmaco-topology of sulfonylurea receptors. Separate domains of the regulatory subunits of KATP channel isoforms are required for selective interaction with K+ channel openers. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 717–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakos E. et al. (1998) Functional multidrug resistance protein (MRP1) lacking the N-terminal transmembrane domain. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 32167–32175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K.W., Csanady,L., Seto-Young,D., Nairn,A.C. and Gadsby,D.C. (2000) Severed molecules functionally define the boundaries of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator’s NH2-terminal nucleotide binding domain. J. Gen. Physiol., 116, 163–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang G. and Roth,C.B. (2001) Structure of MsbA from E.coli: a homolog of the multidrug resistance ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters. Science, 293, 1793–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement J.P., Kunjilwar,K., Gonzalez,G., Schwanstecher,M., Panten,U., Aguilar-Bryan,L. and Bryan,J. (1997) Association and stoichiometry of KATP channel subunits. Neuron, 18, 827–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M.V., Baines,C.P. and Downey,J.M. (2000) Ischemic preconditioning: from adenosine receptor of KATP channel. Annu. Rev. Physiol., 62, 79–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S.P. and Deeley,R.G. (1998) Multidrug resistance mediated by the ATP-binding cassette transporter protein MRP. BioEssays, 20, 931–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M. and Allikmets,R. (2001) Complete characterization of the human ABC gene family. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr., 33, 475–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denning G.M., Anderson,M.P., Amara,J.F., Marshall,J., Smith,A.E. and Welsh,M.J. (1992) Processing of mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is temperature-sensitive. Nature, 358, 761–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doupnik C.A., Davidson,N. and Lester,H.A. (1995) The inward rectifier potassium channel family. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol., 5, 268–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne M.J. and Petersen,O.H. (1986) Intracellular ADP activates K+ channels that are inhibited by ATP in an insulin-secreting cell line. FEBS Lett., 208, 59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enkvetchakul D., Loussouarn,G., Makhina,E., Shyng,S.L. and Nichols,C.G. (2000) The kinetic and physical basis of KATP channel gating: toward a unified molecular understanding. Biophys. J., 78, 2334–2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez S.B., Hollo,Z., Kern,A., Bakos,E., Fischer,P.A., Borst,P. and Evers,R. (2002) Role of the N-terminal transmembrane region of the multidrug resistance protein MRP2 in routing to the apical membrane in MDCKII cells. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 31048–31055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French P.J., van Doorninck,J.H., Peters,R.H., Verbeek,E., Ameen,N.A., Marino,C.R., de Jonge,H.R., Bijman,J. and Scholte,B.J. (1996) A delta F508 mutation in mouse cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator results in a temperature-sensitive processing defect in vivo. J. Clin. Invest., 98, 1304–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby D.C. and Nairn,A.C. (1999) Control of CFTR channel gating by phosphorylation and nucleotide hydrolysis. Physiol Rev., 79, S77–S107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M., Yamazaki,M., Loe,D.W., Westlake,C.J., Grant,C.E., Cole,S.P. and Deeley,R.G. (1998) Multidrug resistance protein. Identification of regions required for active transport of leukotriene C4. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 10733–10740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble F.M., Ashfield,R., Ammala,C. and Ashcroft,F.M. (1997a) Properties of cloned ATP-sensitive K+ currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol., 498, 87–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble F.M., Tucker,S.J. and Ashcroft,F.M. (1997b) The essential role of the Walker A motifs of SUR1 in KATP channel activation by Mg-ADP and diazoxide. EMBO J., 16, 1145–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins C.F. (1992) ABC transporters: from microorganisms to man. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol., 8, 67–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N., Gonoi,T., Clement,J.P., Namba,N., Inazawa,J., Gonzalez,G., Aguilar-Bryan,L., Seino,S. and Bryan,J. (1995) Reconstitution of IKATP: an inward rectifier subunit plus the sulfonylurea receptor. Science, 270, 1166–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John S.A., Monck,J.R., Weiss,J.N. and Ribalet,B. (1998) The sulphonylurea receptor SUR1 regulates ATP-sensitive mouse Kir6.2 K+ channels linked to the green fluorescent protein in human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293). J. Physiol., 510, 333–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane C., Shepherd,R.M., Squires,P.E., Johnson,P.R., James,R.F., Milla,P.J., Aynsley-Green,A., Lindley,K.J. and Dunne,M.J. (1996) Loss of functional KATP channels in pancreatic β-cells causes persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy. Nat. Med., 2, 1344–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liman E.R., Tytgat,J. and Hess,P. (1992) Subunit stoichiometry of a mammalian K+ channel determined by construction of multimeric cDNAs. Neuron, 9, 861–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locher K.P., Lee,A.T. and Rees,D.C. (2002) The E.coli BtuCD structure: a framework for ABC transporter architecture and mechanism. Science, 296, 1091–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz E. and Terzic,A. (1999) Physical association between recombinant cardiac ATP-sensitive K+ channel subunits Kir6.2 and SUR2A. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol., 31, 425–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz E., Alekseev,A.E., Krapivinsky,G.B., Carrasco,A.J., Clapham,D.E. and Terzic,A. (1998) Evidence for direct physical association between a K+ channel (Kir6.2) and an ATP-binding cassette protein (SUR1) which affects cellular distribution and kinetic behavior of an ATP-sensitive K+ channel. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 1652–1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D., Zerangue,N., Lin,Y.F., Collins,A., Yu,M., Jan,Y.N. and Jan,L.Y. (2001) Role of ER export signals in controlling surface potassium channel numbers. Science, 291, 316–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makhina E.N. and Nichols,C.G. (1998) Independent trafficking of KATP channel subunits to the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 3369–3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T., Nagashima,K. and Seino,S. (1999) The structure and function of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel in insulin-secreting pancreatic β-cells. J. Mol. Endocrinol., 22, 113–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T. et al. (2002) Mouse model of Prinzmetal angina by disruption of the inward rectifier Kir6.1. Nat. Med., 8, 466–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau C., Jacquet,H., Prost,A.L., D’hahan,N. and Vivaudou,M. (2000) The molecular basis of the specificity of action of KATP channel openers. EMBO J., 19, 6644–6651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols C.G., Shyng,S.L., Nestorowicz,A., Glaser,B., Clement,J.P., Gonzalez,G., Aguilar-Bryan,L., Permutt,M.A. and Bryan,J. (1996) Adenosine diphosphate as an intracellular regulator of insulin secretion. Science, 272, 1785–1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noma A. (1983) ATP-regulated K+ channels in cardiac muscle. Nature, 305, 147–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otonkoski T. et al. (1999) A point mutation inactivating the sulfonylurea receptor causes the severe form of persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy in Finland. Diabetes, 48, 408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quayle J.M., Nelson,M.T. and Standen,N.B. (1997) ATP-sensitive and inwardly rectifying potassium channels in smooth muscle. Physiol. Rev., 77, 1165–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raab-Graham K.F., Cirilo LJ, Boettcher AA, Radeke CM, Vandenberg CA. (1999) Membrane topology of the amino-terminal region of the sulfonylurea receptor. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 29122–29129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J. and Russell,D.W. (2001) Molecular Cloning. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Schwanstecher M., Sieverding,C., Dorschner,H., Gross,I., Aguilar-Bryan,L., Schwanstecher,C. and Bryan,J. (1998) Potassium channel openers require ATP to bind to and act through sulfonylurea receptors. EMBO J., 17, 5529–5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwappach B., Zerangue,N., Jan,Y.N. and Jan,L.Y. (2000) Molecular basis for KATP assembly: transmembrane interactions mediate association of a K+ channel with an ABC transporter. Neuron, 26, 155–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seino S. (1999) ATP-sensitive potassium channels: a model of heteromultimeric potassium channel/receptor assemblies. Annu. Rev. Physiol., 61, 337–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N., Crane,A., Clement,J.P., Gonzalez,G., Babenko,A.P., Bryan,J. and Aguilar-Bryan,L. (1999) The C terminus of SUR1 is required for trafficking of KATP channels. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 20628–20632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyng S., Ferrigni,T. and Nichols,C.G. (1997) Regulation of KATP channel activity by diazoxide and MgADP. Distinct functions of the two nucleotide binding folds of the sulfonylurea receptor. J. Gen. Physiol., 110, 643–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp S. and Ashcroft,F.M. (2000) Direct interaction of Na-azide with the KATP channel. Br. J. Pharmacol., 131, 1105–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker S.J., Gribble,F.M., Zhao,C., Trapp,S. and Ashcroft,F.M. (1997) Truncation of Kir6.2 produces ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the absence of the sulphonylurea receptor. Nature, 387, 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K., Ji,J.J., Yuan,H., Miki,T., Sato,S., Horimoto,N., Shimizu,T., Seino,S. and Inagaki,N. (2001) Protective role of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in hypoxia-induced generalized seizure. Science, 292, 1543–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerangue N., Schwappach,B., Jan,Y.N. and Jan,L.Y. (1999) A new ER trafficking signal regulates the subunit stoichiometry of plasma membrane KATP channels. Neuron, 22, 537–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingman L.V., Alekseev,A.E., Bienengraeber,M., Hodgson,D., Karger,A.B., Dzeja,P.P. and Terzic,A. (2001) Signaling in channel/enzyme multimers: ATPase transitions in SUR module gate ATP-sensitive K+ conductance. Neuron, 31, 233–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingman L.V., Hodgson,D.M., Bienengraeber,M., Karger,A.B., Kathmann,E.C., Alekseev,A.E. and Terzic,A. (2002) Tandem function of nucleotide binding domains confers competence to sulfonylurea receptor in gating ATP-sensitive K+ channels. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 14206–14210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]