Abstract

The Vip3A protein, secreted by Bacillus spp. during the vegetative stage of growth, represents a new family of insecticidal proteins. In our investigation of the mode of action of Vip3A, the 88-kDa Vip3A full-length toxin (Vip3A-F) was proteolytically activated to an approximately 62-kDa core toxin either by trypsin (Vip3A-T) or lepidopteran gut juice extracts (Vip3A-G). Biotinylated Vip3A-G demonstrated competitive binding to lepidopteran midgut brush border membrane vesicles (BBMV). Furthermore, in ligand blotting experiments with BBMV from the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta (Linnaeus), activated Cry1Ab bound to 120-kDa aminopeptidase N (APN)-like and 250-kDa cadherin-like molecules, whereas Vip3A-G bound to 80-kDa and 100-kDa molecules which are distinct from the known Cry1Ab receptors. In addition, separate blotting experiments with Vip3A-G did not show binding to isolated Cry1A receptors, such as M. sexta APN protein, or a cadherin Cry1Ab ecto-binding domain. In voltage clamping assays with dissected midgut from the susceptible insect, M. sexta, Vip3A-G clearly formed pores, whereas Vip3A-F was incapable of pore formation. In the same assay, Vip3A-G was incapable of forming pores with larvae of the nonsusceptible insect, monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus (Linnaeus). In planar lipid bilayers, both Vip3A-G and Vip3A-T formed stable ion channels in the absence of any receptors, supporting pore formation as an inherent property of Vip3A. Both Cry1Ab and Vip3A channels were voltage independent and highly cation selective; however, they differed considerably in their principal conductance state and cation specificity. The mode of action of Vip3A supports its use as a novel insecticidal agent.

In recent years, a number of insecticidal proteins expressed during the vegetative growth phase of Bacillus thuringiensis have been identified (10, 11, 40, 46, 48). These secreted vegetative insecticidal proteins (Vips) contrast with the widely investigated B. thuringiensis δ-endotoxins, or insecticidal crystal proteins, which form parasporal inclusions primarily during the sporulation phase (38). The Vips have shown a broad insecticidal spectrum, including activity toward a wide variety of lepidopteran and also coleopteran pests (10, 11, 46, 48). The Vip3A toxin, an 88-kDa protein, is secreted into the culture medium by B. thuringiensis and displays high toxicity against a range of lepidopteran insects (10).

B. thuringiensis δ-endotoxins have been successfully used to control many crop pests by either traditional spray application or transgenic plant approaches. However, a number of cases of insect resistance to the B. thuringiensis δ-endotoxins have been reported as a result of laboratory and, more rarely, field selections (13). Therefore, searching for a new family of insecticidal toxins, with a mode of action different from δ-endotoxins, is one facet of current strategies designed to delay resistance development. The mode of action of δ-endotoxin is comprised of multiple steps (15, 38). Crystal proteins are solubilized in the alkaline and often reducing lepidopteran gut environment, and then they are rapidly processed into the active form by midgut proteases. The activated toxin fragment then binds to specific receptors located on the brush border membrane of midgut epithelial cells. These membrane-bound toxins form ion channels and/or pores, leading to disruption of the midgut transmembrane potential and eventual insect death.

One of the interesting features of the Vip3A protein is that it shares no sequence homology with the known δ-endotoxins (10). The action of Vip3A has been examined and shown to be at the level of insect midgut epithelium, where binding to midgut cells is followed by progressive degeneration of the epithelial layer (48). These molecular events are manifested behaviorally as well, as increasing amounts of Vip3A in an artificial diet correlate with interruption of feeding and gut clearance for susceptible insects (48). In order to further understand the mode of action of Vip3A, we have examined selected steps critical to the mode of action of δ-endotoxins, using the well-known Cry1Ab protein for comparison. Proteolytic activation, binding to isolated insect midgut brush border proteins, and an ability to form pores in two different in vitro assays have been investigated. Our findings indicate that while Vip3A shares some steps in the mode of action with Cry1Ab δ-endotoxin, it utilizes a different molecular target and forms distinct ion channels compared to Cry1Ab.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bioassays.

First-instar larvae of Manduca sexta obtained from the North Carolina State University insectary (Raleigh, N.C.), Ostrinia nubilalis obtained from Syngenta Research Station (Bloomington, Ill.), Agrotis ipsilon, Helicoverpa zea, and Spodoptera frugiperda obtained from French Agricultural Research Services (Lamberton, Minn.), and Danaus plexippus obtained from the University of Kansas insectary (Lawrence, Kans.) were used for bioassays. Activity of Vip3A toxin was determined by surface treatment assays. The toxin was serially diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer, pH 7.4, and 100 μl of each dilution was applied over the surface of an artificial black cutworm diet (Southland Products, Inc., Lake Village, Ark.) that was poured into footed petri dishes (Gelman Filtration Products, Ann Arbor, Mich.). Typically, 10 larvae were added to each dish, and mortality was measured after 5 days and compared to controls. For H. zea, larvae were placed in individual wells of a 24-well cell culture cluster plate (Corning Costar, Corning, N.Y.) similarly filled with diet and surface treated. Three replicates were used to support 50% lethal concentration (LC50) determinations calculated by probit analysis (14) with the EPA probit analysis program (version 1.5; Washington, D.C.).

Toxin preparation and proteolysis.

Cry1Ab toxin was expressed in Escherichia coli, purified, and trypsin activated as described previously (23). Vip3A was overexpressed in E. coli as described by Yu et al. (48) and then purified with 18% ammonium sulfate precipitation followed by phenyl hydrophobic interaction column chromatography and DEAE ion-exchange chromatography. In order to obtain the truncated Vip3A toxin (ca. 62 kDa), the 88-kDa full-length toxin (Vip3A-F) was incubated with 1% trypsin (wt/wt) in PBS buffer, pH 7.4, at 37°C degree for 1 h; this toxin form was henceforth named Vip3A-T. Alternatively, lepidopteran gut juice was used to obtain a truncated Vip3A toxin (Vip3A-G; ca. 62 kDa). Gut juice was collected from M. sexta or O. nubilalis larvae by gently inducing regurgitation, and the gut juice was then centrifuged at 13,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C before use. Gut juice extracts (supernatants) were diluted 50-fold with PBS, added to the Vip3A-F toxin, and incubated for 1 h at 29°C. Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (1 μl, resuspended per the manufacturer's instructions; Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) was added to stop the reaction. Toxin stability (all forms) was assessed on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-8 to 12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gradient. Mark12 molecular weight markers (Novex) were used.

Biotinylation of toxins.

Vip3A-F, Vip3A-G, and activated Cry1Ab toxin (each at 1 mg/ml) were dialyzed against 0.1 M borate buffer, pH 8.0, and then biotinylated using a biotin labeling kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) per the manufacturer's instructions. Nonreacted biotin-7-NHS reagent was removed by gel filtration on a prepared Sephadex G-25 column per the manual instructions (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

BBMV-binding assays.

Brush border membrane vesicles (BBMV) were prepared from last-instar M. sexta and O. nubilalis larval midguts by the differential magnesium precipitation method as described by Wolfersberger et al. (47). The final pellet was resuspended in the binding buffer, consisting of 8 mM NaHPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, and 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.4), and the protein concentration was measured using the Coomassie protein assay reagent (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, Ill.). For qualitative estimation of competitive binding, 5 nM biotinylated Cry1Ab or Vip3A-G toxin was incubated with 10 μg of BBMV in the presence or absence of 250-fold excess unlabeled Cry1Ab or Vip3A-G, respectively. After 1 h of incubation at room temperature (RT), reaction mixtures were centrifuged at 13,500 × g for 10 min. The pellets were washed three times with binding buffer containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Final pellets were resuspended in the binding buffer without BSA and mixed with Laemmli sample buffer (21) prior to SDS-PAGE (8 to 16% gradient; Tris-glycine Novex gels; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). For visualization, proteins were transferred to Novex polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Invitrogen) and probed with streptavidin-conjugated peroxidase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) and the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence kit (Pierce).

Identification of Vip3A and Cry1Ab toxin-binding proteins by BBMV ligand blotting.

BBMV proteins (20 μg) from M. sexta were separated via SDS-PAGE (4 to 12% gradient) and transferred to PVDF membrane. Biotinylated Cry1Ab and Vip3A-G toxins were incubated with the membrane for 4 h at RT. The toxin-binding proteins were visualized with streptavidin-conjugated peroxidase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) and the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence kit (Pierce). SeeBlue Plus2 (Novex) prestained standards were used.

Purification of M. sexta APN receptor.

M. sexta BBMV proteins were resuspended at 1 mg/ml in 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 3.4 mM EDTA, with Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). BBMV proteins were solubilized with 0.5% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), pH 8.5, overnight at 4°C, and insoluble materials were removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min. Supernatants were concentrated by Amicon YM-30 filtration (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) and applied to a MonoQ HR 10/30 ion-exchange column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 3.4 mM EDTA, 0.4 mg of CHAPS/ml. Proteins were eluted at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min using a step gradient of 1 M NaCl in the same buffer. Fractions were then analyzed for aminopeptidase activity by a leucine-p-nitroanilide assay described previously (43). Aminopeptidase N (APN)-active fractions were probed with anti-APN polyclonal serum using ligand blotting overlays. Appropriate fractions were reconcentrated and repurified by Superdex 200 in HEPES, pH 7.4 buffer. A single peak corresponding to a 120-kDa protein was collected.

Cloning and expression of a cadherin ectodomain.

Total RNA was prepared from a last-instar M. sexta larva using the SV total RNA isolation system (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.), and cDNA was synthesized using the SMART cDNA library construction kit (Clontech, BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, Calif.). The δ-endotoxin-binding region from the cadherin ectodomain of BT-R1 described by Dorsch et al. (7) was PCR amplified from the M. sexta cDNA with a 5′ ectodomain oligonucleotide (5′GGATCCGATGGGCCTCGATCCTGTTCGCAACAGGTT3′) and a 3′ ectodomain oligonucleotide (5′GGCTCGAGCTAGAACACGAAGTAGACGCGGTTCTGC3′). The PCR product was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) for sequencing. Then, the ectodomain insert was cut with BamHI-XhoI and cloned into the pTriEx-2 vector (Novagen, Inc., Madison, Wis.) and transformed into either Origami(DE3)pLacI or Tuner(DE3)pLacI E. coli cells (Novagen, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cultures were induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 3 h at 37°C, and the cells were disrupted with BugBuster protein extraction reagent (Novagen, Inc.). This toxin-binding region (TBR) from the cadherin ectodomain was then purified from the soluble fraction using a His·Bind resin (Novagen, Inc.).

Binding of toxins to the purified M. sexta APN and cadherin ectodomain TBR.

Purified APN protein (2.5 μg) was blotted onto PVDF membrane (Invitrogen) following SDS-PAGE. The membrane was blocked with 3% BSA for 1 h and incubated with 10 nM biotinylated Vip3A-G or Cry1Ab toxin for 2 h at RT. After washing with TTBS buffer (20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl [pH 7.5], 0.05% Tween 20, and 0.01% Triton X-100), the bound toxins were probed with streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) and the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence kit (Pierce). Similarly, cadherin ectodomain TBR protein (6 μg) was blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane following SDS-PAGE. After blocking, the membrane was incubated with 10 nM biotinylated Cry1Ab or biotinylated Vip3A-G protein for 2 h at RT. After washing the membrane, bound toxins were probed with streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase and an ECL chemiluminescence kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Voltage clamping assays.

Voltage clamping assays were performed as described previously (3). Late-fourth-instar M. sexta or D. plexippus larvae were dissected, and midguts were mounted on a disk 3.9 mm in diameter. (Note: M. sexta and D. plexippus were chosen as the susceptible and nonsusceptible insects for these assays due to the size limitations of the other lepidopteran larvae available.) A standard chamber buffer (32 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 240 mM sucrose in 5 mM Tris, pH 8.3) was used to bathe the isolated midgut. After 20 to 30 min, allowing for stabilization of the midgut conditions, 15 nM Vip3A-F, Vip3A-G, or Cry1Ab toxin was added to the lumen side of the chamber and the change in short circuit current (Isc) over time (in minutes) was recorded. During the experiment, the chamber solution was bubbled continuously with oxygen. The Isc was tracked with a Kipp and Zonen chart recorder (Bohemia, N.Y.), and data were collected with the MacLab data acquisition system (ADInstruments, Grand Junction, Colo.) on a Macintosh computer.

Planar lipid bilayers.

Planar lipid bilayers were formed in aqueous solution by painting a 1:1 molar solution (35 mg/ml in decane) of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phospatidylcholine:1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phospatidylethanolamine (Avanti Polar Lipids, Pelham, Ala.) across a 0.20- to 0.25-mm aperture in a Delrin plastic bilayer chamber (cups and chambers purchased from Warner Instruments, Hamden, Conn.). Bilayer thinning was monitored visually with a 30× zoom stereo microscope (GZ40; Leica Microsystems, Inc., Bannockburn, Ill.) and through membrane capacitance measurements (3910 bilayer expander module; Dagan Corp., Minneapolis, Minn.). The bilayer buffer typically consisted of 300 mM KCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.5. Cry1Ab and Vip3A toxins were typically added from 50 mM Tris, pH 8.5, solutions to the cis side of the bilayer to a concentration of 75 to 150 ng/μl. All additions were accompanied by 30 s to 1 min of stirring. Bilayer membranes were voltage clamped in the outside-out submode using a Dagan 3900A integrating patch-clamp amplifier (Dagan Corp.) with Ag/AgCl electrodes connected to cis or trans sides via agar bridges. The trans side served as the ground with a positive membrane potential affording a positive current from trans to cis. (Note: the Dagan 3900A achieves this by applying the inverted command to the bath, or cis, electrode.) Currents were typically low-pass Bessel filtered at 500 Hz (Dagan 3900A) and then sampled at 2.5 kHz using Axoscope 8 data acquisition software (Axon Instruments, Union City, Calif.). Following observation of single-channel-type currents, current-voltage relationships were formed from mean current amplitudes of the predominant single channel type present over stepped voltages typically between ±80 mV.

Determination of Vip3A and Cry1Ab channel ionic selectivity.

For examination of cation selectivity of subsequently added channels, the planar lipid bilayer membrane was first formed in the presence of symmetrical buffer with only 100 mM KCl, and then 4 M KCl was added to the cis side only to bring its net concentration up to 300 mM KCl. For examination of cation specificity, the membrane was first formed in the presence of symmetrical 5 mM CaCl2, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.5, and then 4 M KCl and 4 M NaCl were added to the cis and trans sides, respectively, to achieve the asymmetrical 300 mM KCl:300 mM NaCl condition. Current-voltage relations were plotted, and reversal potentials (Erev) were thereby determined under the various ionic conditions. These data were then applied to modified forms of the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz voltage equation (1) or (2) (18, 22) to determine cation selectivity (PK/PCl) or cation specificity (PK/PNa), respectively.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

Thermodynamic activities (a) were calculated using the corresponding molar activity coefficients (45) for the applied potential (v) and ground sides (o) of the membrane in equation 1 or for outside (cis) and inside (trans) sides in equation 2. F, R, and T are Faraday's constant, the Gas constant, and temperature in degrees Kelvin. All experiments were carried out at RT (≈23°C).

RESULTS

Biological activity of Vip3A.

Among a selected group of lepidopteran pests, Vip3A was most toxic to A. ipsilon and S. frugiperda but without detectable activity toward O. nubilalis and D. plexippus (Table 1). The inactivity against O. nubilalis has been suggested previously (10, 48), whereas to our knowledge, our data afford the first report documenting Vip3A inactivity toward D. plexippus (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Insecticidal activity of Vip3A-F toward several lepidopteran species in the artificial diet bioassay

| Insect | LC50 (95% CL)a |

|---|---|

| A. ipsilon | 17.1 (7.7-30.4) |

| S. frugiperda | 55.9 (33.7-88.9) |

| H. zea | 112.5 (65.9-179.4)b |

| M. sexta | 176.3 (142.3-218.3)b |

| O. nubilalis | NDc |

| D. plexippus | ND |

LC50 expressed in nanograms per square centimeter, with 95% upper and lower confidence limit (CL) in parentheses.

In addition, 100% mortality was attainable when Vip 3A-F was presented to either H. zea or M. sexta in single high-dose bioassays (e.g., 1,000 ng/cm2).

ND, nondetectable mortality even after a high dose of 1,000 ng/cm2.

Proteolysis of Vip3A toxin by lepidopteran gut proteases.

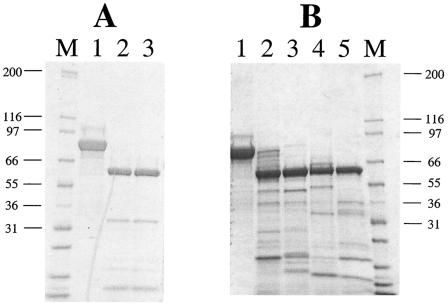

Proteolytic activation of the 88-kDa Vip3A-F to an approximately 62-kDa form occurred via the action of either trypsin (Fig. 1A) or gut juice extracts from the susceptible M. sexta, or nonsusceptible, O. nubilalis, insects (Fig. 1B). Other digestion assays employing gut juice extracts from the susceptible insect H. zea exhibited very similar protein patterns, whereas the patterns produced after digestion with the susceptible A. ipsilon or S. frugiperda gut juice extracts showed less stable Vip3A-G protein with more degradation products evident on the gel (data not shown). These data indicate that the proteolytic activation process alone is not a key factor in insect toxicity and specificity. Also, after in vivo feeding of biotinylated Vip3A-F to M. sexta, Vip3A-F was converted to the 62-kDa truncated form, confirming this activation step (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Proteolytic activation of Vip3A-F toxin by trypsin (A) or lepidopteran gut juice extracts (B). (A) A 2.5-μg aliquot of Vip3A-F toxin (lane 1) was incubated with 1% trypsin for 1 h (lane 2) or overnight (lane 3) at 37°C. M = MW markers (10−3) as indicated. (B) A 2.5-μg aliquot of Vip3A-F toxin (lane 1) was treated with O. nubilalis (lanes 2 and 4) or M. sexta (lanes 3 and 5) gut juice extracts for 1 h (lanes 2 and 3) or overnight (lanes 4 and 5). After digestion, reactions were stopped by adding Complete protease inhibitor (Roche Molecular Biochemicals), and samples were separated on SDS-8 to 12% PAGE.

BBMV-binding assays.

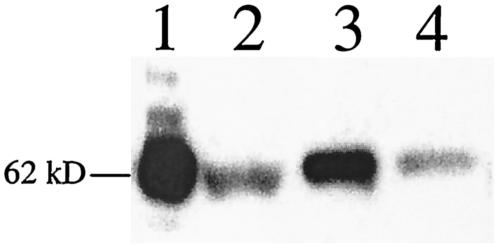

Vip3A toxin-binding properties have been assessed by competition binding assays using biotinylated Vip3A-G. The biotinylated Vip3A-G bound to M. sexta BBMV in a competitive fashion, as a 250-fold molar excess of unlabeled Vip3A-G significantly reduced the remaining signal (Fig. 2). Biotinylated Vip3A-G also bound to O. nubilalis BBMV; however, the total amount of bound Vip3A-G was significantly reduced for this nonsusceptible insect compared to M. sexta (Fig. 2). Vip3A-G binding to O. nubilalis BBMV was also shown to be competitive (Fig. 2). In addition, BBMV-binding assays with another susceptible insect, H. zea, also showed competitive binding (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Binding of biotinylated Vip3A-G to M. sexta (lanes 1 and 2) and O. nubilalis BBMV (lanes 3 and 4). Biotinylated Vip3A-G toxin (5 nM) was incubated with 10 μg of BBMV in the absence (lanes 1 and 3) or presence (lanes 2 and 4) of a 250-fold excess of unlabeled Vip3A-G toxin. BBMV-bound toxins were visualized as described in Materials and Methods.

In vitro binding assays to known Cry1A receptors.

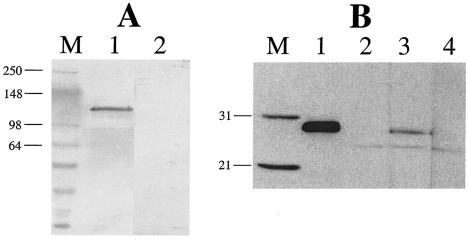

In order to evaluate binding properties of Vip3A-G to known Cry1Ab receptors, additional in vitro toxin-receptor binding assays were conducted. A 120-kDa APN, a known Cry1A receptor, was purified from M. sexta BBMV as confirmed by a single band on SDS-PAGE (data not shown). APN blotting experiments following SDS-PAGE demonstrated that biotinylated Cry1Ab bound strongly to APN as expected, while biotinylated Vip3A-G showed no binding (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, no binding was observed with Vip3A-G to APN where the protein was directly blotted onto PVDF membrane under nondenaturing conditions (data not shown). In addition, in vitro binding to the ectodomain (EC) of the 210-kDa cadherin-like protein was examined. Previously EC11, located near the membrane-proximal extracellular domain of cadherin, was identified as a Cry1Ab TBR (7, 29). In the present study, a 172-amino acid (aa) TBR peptide was expressed in the pTriEX-2 vector, which carries an additional 62 aa from a His tag and S-tag at the N-terminal end. A resulting ca. 25-kDa protein was then purified and blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane. Biotinylated Cry1Ab showed strong binding to this ectodomain TBR, whereas Vip3A-G did not show any binding (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Binding of biotinylated Cry1Ab but not Vip3A-G toxin to isolated Cry1A receptor proteins. (A) M. sexta APN (5 μg) was separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. The blot was blocked with 3% BSA for 1 h and incubated with 10 nM biotinylated Cry1Ab (lane 1) or Vip3A-G (lane 2). Bound toxins were visualized as described in Materials and Methods. (B) The recombinant-expressed TBR of the cadherin ectodomain (6 μg) was separated on SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and then probed before (lanes 1 and 2) or after (lanes 3 and 4) incubation with toxin as described in Materials and Methods. M = MW markers (10−3) as indicated. Lanes 1 and 2, TBR alone; lanes 3 and 4, TBR plus biotinylated Cry1Ab or biotinylated Vip3A-G, respectively. Protein was detected by virtue of an S-tag (lanes M and 1) or with the streptavidin conjugate (lanes 2 to 4) as described in Materials and Methods.

BBMV ligand blotting.

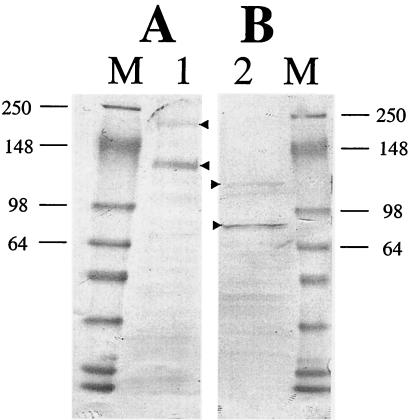

To identify Vip3A-binding proteins present in M. sexta, BBMV ligand blotting was performed. Whereas biotinylated Cry1Ab showed binding to 120-kDa APN-like and 210-kDa cadherin-like molecules, Vip3A-G did not (Fig. 4A). Biotinylated Vip3A-G toxin primarily showed binding to two proteins of ca. 80 and 110 kDa (Fig. 4B). The latter protein was clearly different in migration than the 120-kDa APN-like protein which bound Cry1Ab (from the same blot). A control BBMV blot without biotinylated toxin showed no interaction with the streptavidin-conjugated peroxidase (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

M. sexta BBMV ligand blotting with biotinylated Cry1Ab and Vip3A-G toxins. Twenty micrograms of M. sexta BBMV was separated on an SDS-8 to 12% PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 3% BSA and probed with 10 nM biotinylated Cry1Ab (lane 1) or Vip3A-G (lane 2) for 5 h. Toxin-binding proteins were visualized as described in Materials and Methods. M = MW markers (10−3) as indicated.

Voltage clamping analysis.

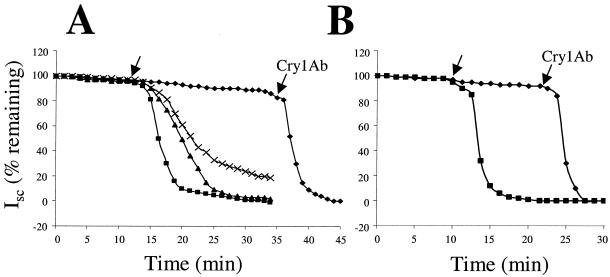

Voltage clamping experiments were performed with both M. sexta and D. plexippus larval midguts (Fig. 5A and B, respectively). The slope of the inhibition of Isc over time in response to lumen-side toxin addition was calculated for both insects. In these experiments, Isc is proportional to the ion flux from the hemolymph side of the midgut membrane to the lumen side. With M. sexta midgut and 15 nM Cry1Ab, the Isc inhibition had a slope of −8.1 μA/min. Cry1Ab serves as a positive control in these assays due to its known pore-forming activity toward M. sexta (33, 34). Vip3A-F did not show any pore-forming activity even at 150 nM; however, subsequent addition of Cry1Ab toxin to the Vip3A-F-treated midgut demonstrated responsiveness (Fig. 5A) with an Isc inhibition slope of −7.6 μA/min. Vip3A-G differed from Vip3A-F in that it clearly possessed pore-forming activity at 15 nM with an Isc inhibition slope of −1.1 μA/min. With a 10-fold molar increase, Vip3A-G showed only a slightly steeper response, with an Isc inhibition slope of −1.8 μA/min (Fig. 5A). To further examine the relationship between Vip3A biological activity and these in vitro assays, the voltage-clamp response of a nonsusceptible insect larval midgut, D. plexippus, was tested. While Cry1Ab (which can exhibit toxicity to D. plexippus larvae) showed a pore-forming response with an Isc inhibition slope of −8.8 μA/min (Fig. 5B), Vip3A-G (nontoxic to D. plexippus) failed to show any pore formation. Again, a subsequent addition of Cry1Ab toxin to this intact midgut demonstrated the typical Cry1Ab Isc inhibition response (slope = −8.3 μA/min) (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of Isc across M. sexta (A) and D. plexippus (B) as measured by voltage clamping of dissected midguts. To M. sexta, a total of 15 nM Cry1Ab toxin (▪) or Vip3A-G (×) or 150 nM Vip3A-F (⧫) or Vip3A-G (▴) was injected (first arrow) into the lumen side of the chamber, and the drop in Isc was measured over time. For Vip3A-F (⧫), 15 nM Cry1Ab was also added at 35 min to verify membrane viability (second arrow). To D. plexippus, a total of 15 nM Cry1Ab toxin (▪) or 150 nM Vip3A-G toxin (⧫) was injected. After 22.5 min with no response from the Vip3A-G injection, 15 nM Cry1Ab toxin (second arrow) was added. The Isc measured before the addition of the toxin was considered 100%.

Ion channels formed by activated Vip3A and activated Cry1Ab.

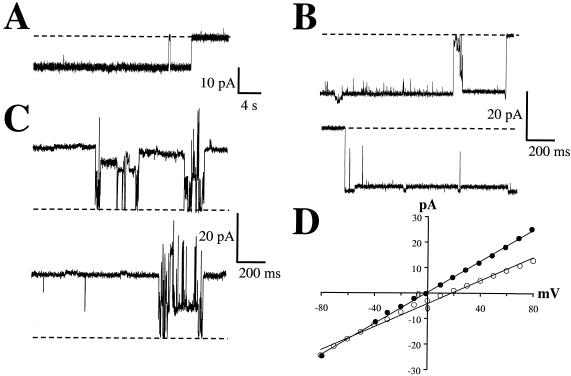

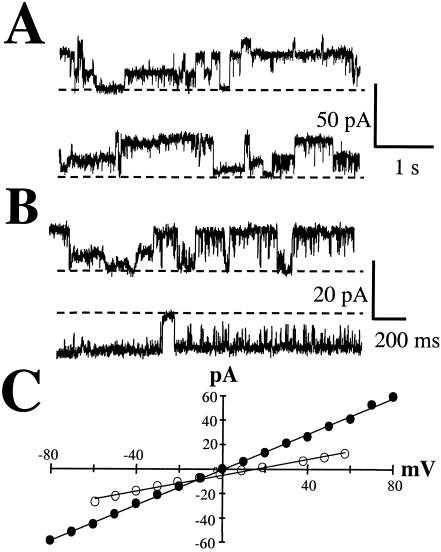

Vip3A toxin which was activated in vitro by either incubation with lepidopteran gut fluid (Fig. 6A) or trypsin (Fig. 6B and C) demonstrated the ability to form stable ion channels in the planar lipid bilayer system. This is in contrast to full-length Vip3A, which to date has not shown ion channel activity in this same assay system. The channels formed by activated Vip3A were characterized by long open times (Fig. 6) and a predominant open state of 312 ± 5 pS (n = 3) under conditions of symmetrical 300 mM KCl. As the channels formed under these two activation methods did not appear to differ, the majority of experiments were conducted with the trypsinized version of Vip3A. Gating to other discrete open states was present on occasion (Fig. 6 C), suggesting that the main open state of activated Vip3A is represented by a complex structure that is capable of some degree of ion conduction prior to the fully formed main open state of the channel. Under symmetrical conditions, the channels were voltage independent over the range of voltages tested (Fig. 6B to D). Activated Cry1Ab formed ion channels with an apparent variety of open states (Fig. 7); however, a main conductance state of approximately 730 pS was observed under conditions of symmetrical 300 mM KCl. As has been reported for other Cry1-type channels (17, 31, 41), Cry1Ab channels gave no indication of a strong voltage dependence over the voltage range of ±80 mV (Fig. 7B and C).

FIG. 6.

In vitro-activated Vip3A ion channels formed in planar lipid bilayers. (A) Channels seen after activation with M. sexta gut fluid. Channels open down; holding voltage (Vh) = −40 mV. (B and C) Channels seen after activation with trypsin. Panel B contains two consecutive traces (channels open down) with Vh = −80 mV, whereas panel C contains two consecutive traces (channels open up) with Vh = +80 mV. Dashed lines indicate closed current level. (D) Current-voltage relations for the principal conducting state of trypsin-activated Vip3A under symmetrical (•) or asymmetrical (○) KCl conditions as described in Materials and Methods. Linear regression equations were y = 0.306x + 0.244, r2 = 0.998 (•); or y = 0.227x − 4.22, r2 = 0.992 (○), respectively.

FIG. 7.

Cry1Ab channels formed in planar lipid bilayers. (A) Variation observed in the conductance levels of Cry1Ab channels. Vh = +40 mV in the two consecutive traces (channels open up). (B) In a separate experiment, Cry1Ab channels are displayed at +20 mV (upper trace, channels open up) or at −20 mV (lower trace, channels open down). Dashed lines indicate closed current level. (C) Current-voltage relations for the principal conducting state of trypsin-activated Cry1Ab under symmetrical (•) or asymmetrical (○) KCl conditions as described in Materials and Methods. Linear regression equations were y = 0.730x − 0.806, r2 = 0.999 (•); or y = 0.330x − 5.48, r2 = 0.991 (○), respectively.

Ion selectivity of Vip3A and Cry1Ab channels.

Both Vip3A and Cry1Ab form channels which are highly cation selective. When examined in the presence of a threefold KCl gradient (see Materials and Methods), the reversal potential of both channel types shifted in a direction indicative of cation selectivity (Fig. 6D and 7C; Table 2), which translated to PK/PCl ratios of 10.7 ± 4.6 and 7.0 ± 2.6 for Vip3A and Cry1Ab, respectively (Table 2). Neither channel was ideally cation selective, however, as was confirmed by comparison with gramicidin D in the same recording system (Table 2). Vip3A channels indicated very little specificity for potassium over sodium, with PK/PNa equal to 1.3 ± 0.2 (Table 2), whereas Cry1Ab channels exhibited more preference for conducting potassium, with PK/PNa equal to 1.9 ± 0.3 (Table 2). The specificity shown by gramicidin D channels (PK/PNa = 3.3) (Table 2) is close to that reported by Hille (18).

TABLE 2.

Reversal potentials (Erev) and permeability ratios (PK/PX) in the presence of indicated salt gradientsa

| Channel | 1:1 KCl | 3:1 KCl

|

1:1 KCl:NaCl

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erev (mV) | Erev (mV) | PK/PCl | Erev (mV) | PK/PNa | |

| Cry1Ab | 1.1 | 17.8 ± 2.1 (3)b | 7.0 ± 2.6 | 15.3 ± 3.8 (3) | 1.9 ± 0.3 |

| Vip3A-T | 0.2 ± 1.6 (3) | 19.9 ± 1.7 (3) | 10.7 ± 4.6 | 4.8 ± 4.5 (3) | 1.3 ± 0.2 |

| Gramicidin D | 0.3 | 22.8 | 23.4 | 30.0 | 3.3 |

Salt gradients were established cis:trans as described in Materials and Methods.

All values followed by n in parentheses are mean ± standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the mode of action of Vip3A, a member of a new family of B. thuringiensis toxins, has been investigated. As with δ-endotoxins, the mode of action of Vip3A appears to be complex, involving a number of discrete steps. As might be expected with a secreted bacterial protein, Vip3A is soluble across a broad range of pH values from at least 5.0 to 10.0 (data not shown); this is important, as the toxin works following ingestion. Next, Vip3A is processed in the lepidopteran gut. Yu et al. (48) previously demonstrated that Vip3A is processed by lepidopteran gut juice extract (at pH 10.0) to four dominant bands of approximately 62, 45, 33, and 22 kDa while retaining activity toward susceptible insects. Recently, Selvapandiyan et al. (40) analyzed the insecticidal activity of Vip3A and several deletion mutants in a recombinant E. coli expression system. The authors concluded that a minimal toxic fragment exists which contains intact Vip3A residues 40 to 637 but that the toxin fragment may mediate activity toward different pests by different mechanisms. They did not, however, examine the resultant form of these toxins after exposure to lepidopteran gut fluid.

We have found that a dominant, stable, ca. 62-kDa protein (N terminus at aa 199) is formed by the action of susceptible or nonsusceptible lepidopteran gut juice extract as well as by trypsin under pH 7.5 conditions (Fig. 1). In addition, after in vivo feeding assays with M. sexta, the 88-kDa Vip3A-F toxin is also processed into the stable 62-kDa form, as determined from SDS-PAGE analysis of dissected midguts (data not shown). Therefore, the proteolytic step should be included in a description of the fate of ingested toxin. Previously, Yu et al. (48) observed that Vip3A-F processed by the action of gut juice from a nonsusceptible insect, O. nubilalis, could be rendered toxic to susceptible insects. Taken together, these data suggest that while proteolysis of Vip3A occurs, it alone is not a determining factor for insect specificity. We propose, however, that this processing is minimally required for the toxin bioactivity and can be considered as an activation step, as the full-length, unprocessed Vip3A-F is incapable of forming pores in vitro (see below), which we propose to be critical in the Vip3A mode of action.

While no direct information is available regarding the next step, that of crossing the peritrophic membrane, histological data suggest that this does not afford a significant barrier for the toxin with susceptible insects (48). Interaction with midgut epithelium is the next likely step in the Vip3A mode of action. Previous in vivo immunolocalization studies showed that Vip3A binding is restricted to the midgut tissue of a susceptible but not a nonsusceptible insect (A. ipsilon versus O. nubilalis, respectively), indicating that midgut epithelial cells of susceptible insects are the primary target (48). To further elucidate this, we performed in vitro BBMV-binding experiments with Vip3A toward several insects. Biotinylated Vip3A-G binds to BBMV of the susceptible insect, M. sexta, in a competitive fashion, as binding is greatly inhibited by an excess amount of unlabeled Vip3A-G (Fig. 2). In contrast to a previous report (48), binding of Vip3A-G to the nonsusceptible insect, O. nubilalis, was also observed; however, the amount of this binding was greatly reduced compared to that for M. sexta (Fig. 2). Perhaps this apparent discrepancy can be attributed to differing sensitivities of the detection methods used in the two studies. With B. thuringiensis δ-endotoxin, the absence or reduction of BBMV binding is often observed where nonsusceptible or resistant insects are concerned; however, this general correlation does not always hold true (13, 38).

Since the APN family and cadherin-like glycoprotein have been identified as putative Cry1A toxin receptors in many different insects (5, 20, 29, 37, 42, 43), we also examined whether Vip3A-G could specifically recognize these proteins. First, Vip3A-G does not show binding to a 120-kDa M. sexta APN, whereas Cry1Ab toxin shows strong binding (Fig. 3A). In addition, Vip3A-G does not show binding to a recombinant-expressed cadherin ecto-binding domain similar to that which was reported to interact strongly with Cry1A toxins (7, 29). Again, we found that Cry1Ab toxin shows strong binding to this receptor (Fig. 3B). Other reported cadherin ecto-binding domain regions (16) were not examined in our study. Following these results, in order to identify putative Vip3A-binding proteins, BBMV ligand blotting experiments with M. sexta were performed. Biotinylated Vip3A-G toxin predominantly binds to low-abundance ca. 80- and 110-kDa bands, generating a pattern that clearly differs from that of Cry1Ab (Fig. 4A). Marginal binding is also observed (evident on the original blot) toward a >200-kDa molecule which does not comigrate with a cadherin-like protein. Therefore, our binding data strongly suggest that Cry1Ab and Vip3A do not share the same binding sites. Recently, a high-molecular-mass glycoconjugate (≈270 kDa) was also reported as a Cry1A receptor in the gypsy moth (44); while we have not specifically examined its potential for interaction with Vip3A, no binding interaction with a protein of this size is indicated for M. sexta (Fig. 4B).

The toxic events that follow binding of Vip3A to insect midgut epithelia could potentially be diverse. The action of Cry toxins as well as several other midgut-active insecticidal agents (2, 28, 32) commonly involve an osmotically induced cell lysis, although these agents are completely unrelated. For δ-endotoxin, catalysis of and modulation of toxin-derived ion channels following receptor binding are established (31, 37, 39); however, additional mechanisms could account for other aspects of toxicity which are observed, such as larval behavioral changes, cessation of feeding, regurgitation, and gut paralysis (1, 9, 12). Based on two separate voltage clamping techniques, our data support the existence of a pore-forming step in the mode of action of Vip3A following the binding to midgut epithelial receptors.

The voltage clamping of isolated insect midgut has been used previously to examine Cry1A δ-endotoxins where direct correlations have been observed between biological activity and pore-forming activity (3, 33, 34). Upon investigation of Vip3A-F and Vip3A-G toxins with isolated M. sexta midgut, we discovered that Vip3A-G is able to form pores while Vip3A-F toxin is not, even after prolonged incubation or increased concentration (Fig. 5A). As Vip3A-G pores are capable of destroying the transmembrane potential, this suggests that pore formation may play a vital role in bioactivity. We found that the kinetics of Vip3A-G pore formation was at least eightfold slower than equimolar Cry1Ab toxin input and did not change markedly even after a 10-fold increase in the concentration of Vip3A toxin present (Fig. 5A). A lower saturation of functional Vip3A-binding sites could be involved, as well as the possibility that assembly of and/or flux through the Vip3A-G pores differs from that with Cry1Ab. This eightfold difference in in vitro kinetics might relate to the more moderate toxicity of Vip3A toward M. sexta (LC50 = 176.3 ng/cm2) (Table 1) compared to that of Cry1Ab (we have determined a lower LC50 value exists with Cry1Ab, 9 ng/cm2, with a 95% confidence interval of 6.5 to 12.2 [data not shown]). Voltage clamping data have again shown that this assay can discriminate between inactive and active toxins, as the Vip3A-G toxin is incapable of pore formation with the nonsusceptible D. plexippus, whereas the response to Cry1Ab is imminent (Fig. 5B).

Planar lipid bilayer experiments validate and extend the conclusions from our isolated midgut voltage clamp data in that processed Vip3A demonstrates the ability to form distinct ion channels in the absence of any receptors. The Vip3A channels are quite stable over time, capable of long open times (>1 s) and of a large conductance status (>300 pS). Therefore, the cumulative effects of Vip3A channel formation provide the simplest explanation for the previously observed pore-forming response. Furthermore, the channels observed in vitro could reasonably be expected to account for the documented histological changes in susceptible insect midgut tissue (48) and the associated toxicity. As the biophysical properties of these channels also differ somewhat from those of Cry1Ab, we can conclude that these channels are structurally and functionally distinct from those of Cry1Ab and, by extension, perhaps from other homologous Cry-type toxins.

A recent review of channel-forming proteins and peptides described 36 known families of pore-forming toxins (36). Excellent structural information exists for a few of these families with transmembrane segments formed by either a barrel of amphipathic β-sheets (e.g., alpha-hemolysin, aerolysin) or a bundle of amphipathic α-helices (e.g., colicin, diphtheria toxin, B. thuringiensis δ-endotoxin). On the basis of detailed mutational analyses (4, 38) and three-dimensional crystal structure information (17, 24), a three-domain structure is supported for δ-endotoxins, with the channel-forming structure localized within domain 1 and likely modulated by domain 3 interactions. While direct structural information is lacking for Vip3A, primary sequence divergence and an examination of predicted secondary structure give no indication of a similar domain organization or a putative α-helical bundle region within the polypeptide sequence, as exists for the Cry-type channels (data not shown). Coupling these observations with the unique binding interactions present for Vip3A toward insect brush border leads one to conclude that Vip3A channels cannot be equated with those of the Cry proteins. Future molecular, biochemical, and biophysical analyses of Vip3A should help elucidate which elements comprise its ion channel structure and binding regions.

Previously, it was proposed that Vip3A might induce an apoptotic pathway after binding to its respective midgut receptors in susceptible insects (11). This proposed mechanism of toxicity is not mutually exclusive from pore formation, as others have shown that pore formation by the bacterial toxins aerolysin or Staphylococcus alpha-toxin, leading to a loss of transmembrane potential, can induce an apoptotic-type cellular response (19, 30). Similarly, toxic agents derived from sporulated B. thuringiensis cultures could induce apoptosis in cultured midgut cells from Heliothis virescens (25, 26). While we hypothesize that the Vip3A pore-forming properties described herein might alone account for observed toxicity, this does not preclude that unique binding events and/or pore formation will be found to mediate other aspects of Vip3A bioactivity.

Several important strategies have been put in place to address concerns of resistance to B. thuringiensis δ-endotoxins, particularly with their presentation in the form of transgenic crops (35). Our data suggest that the unique midgut interactions involved with Vip3A and its receptor(s) render it potentially useful as a second-generation B. thuringiensis toxin for resistance management. Interestingly, in a laboratory culture of Spodoptera exigua, Moar et al. (27) found that the presence of HD1 B. thuringiensis var. kurstaki spores reduced the development of resistance to Cry1C. As this source strain is a potential source of the Vip3A gene (6, 8), it is quite possible that expression of Vip3A may have contributed to these observations. Donovan et al. (6) recently demonstrated that Vip3A production was able to account for a significant component of toxicity via the “spore effect” in an HD1 strain toward A. ipsilon or S. exigua. While the development of resistance to B. thuringiensis δ-endotoxin outside of the laboratory environment has only been documented in isolated cases (13), it remains a concern for the future to better preserve and extend the usefulness of these important insect control agents. In that regard, one strategy involves the presentation of several toxins together, especially if a differing mode of action involving different receptors is available. We have shown that the mode of action of Vip3A differs in several steps compared to Cry1Ab; therefore, incorporation of Vip3A into insect control programs may serve to address δ-endotoxin resistance concerns in addition to its own value as a control agent.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Campbell, F. Carter Gordon, and Renee Westich for assistance in maintaining insect larvae and collection of larval gut fluid. In addition, we are grateful to Donald Dean (Ohio State University) for use of the voltage clamp apparatus for the isolated midgut studies. Also, technical assistance from April Curtiss, Oscar Alzate, and Mohd Amir Abdullah (Ohio State University) was appreciated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aronson, A. I., and Y. Shai. 2001. Why Bacillus thuringiensis toxins are so effective: unique features of their mode of action. FEBS Microbiol. Lett. 195:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackburn, M., E. Golubeva, D. Bowen, and R. H. Ffrench-Constant. 1998. A novel insecticidal toxin from Photorhabdus luminescens, toxin complex a (Tca), and its histopathological effects on the midgut of Manduca sexta. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3036-3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, X. J., M. K. Lee, and D. H. Dean. 1993. Site-directed mutations in a highly conserved region of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin affect inhibition of short circuit current across Bombyx mori midguts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:9041-9045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dean, D. H., F. Rajamohan, M. K. Lee, S.-J. Wu, X. J. Chen, and E. Alcantara. 1996. Probing the mechanism of action of Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal proteins by site-directed mutagenesis—a minireview. Gene 179:111-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denolf, P., K. Hendrickx, J. Van Damme, S. Jansens, M. Peferoen, D. Degheele, and J. Van Rie. 1997. Cloning and characterization of Manduca sexta and Plutella xylostella midgut aminopeptidase N enzymes related to Bacillus thuringiensis toxin-binding proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 248:748-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donovan, W. P., J. C. Donovan, and J. T. Engleman. 2001. Gene knockout demonstrates that vip3A contributes to the pathogenesis of Bacillus thuringiensis toward Agrotis ipsilon and Spodoptera frugiperda. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 78:45-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorsch, J. A., M. Candas, N. B. Griko, W. S. A. Maaty, E. G. Midboe, R. K. Vadlamudi, and L. A. Bulla, Jr. 2002. Cry1A toxins of Bacillus thuringiensis bind specifically to a region adjacent to the membrane-proximal extracellular domain of BT-R1 in Manduca sexta: involvement of a cadherin in the entomopathogenicity of Bacillus thuringiensis. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 32:1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doss, V. A., K. A. Kumar, R. Jayakumar, and V. Sekar. 2002. Cloning and expression of the vegetative insecticidal protein (vip3V) gene of Bacillus thuringiensis in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 26:82-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.English, L., H. Loidl Robbins, M. A. Von Tersch, C. A. Kulesza, D. Ave, D. Coyle, C. S. Jany, and S. L. Slatin. 1994. Mode of action of CryIIA: a Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 24:1025-1035. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Estruch, J. J., G. W. Warren, M. A. Mullins, G. J. Nye, J. A. Craig, and M. G. Koziel. 1996. Vip3A, a novel Bacillus thuringiensis vegetative insecticidal protein with a wide spectrum of activities against lepidopteran insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:5389-5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Estruch, J. J., and C.-G. Yu. September 2001. Plant pest control. U.S. patent 6,291,156 B1.

- 12.Fast, P. G. 1981. The crystal toxin of Bacillus thuringiensis, p. 223-248. In H. D. Burges (ed.), Microbial control of pest and plant diseases. Academic Press, London, England.

- 13.Ferre, J., and J. Van Rie. 2002. Biochemistry and genetics of insect resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 47:501-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finney, D. J. 1971. Probit analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England.

- 15.Gill, S. S., E. A. Cowles, and P. V. Pietrantonio. 1992. The mode of action of Bacillus thuringiensis endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 37:615-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomez, I., J. Miranda-Rios, E. Rudino-Pinera, D. I. Oltean, S. S. Gill, A. Bravo, and M. Soberon. 2002. Hydropathic complementarity determines interaction of epitope 869HITDTNNK876 in Manduca sexta Bt-R1 receptor with loop 2 of domain II of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1A toxins. J. Biol. Chem. 277:30137-30143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grochulski, P., L. Masson, S. Borisova, M. Pusztai-Carey, J.-L. Schwartz, R. Brousseau, and M. Cygler. 1995. Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1A(a) insecticidal toxin: crystal structure and channel formation. J. Mol. Biol. 254:447-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hille, B. 1992. Ionic channels of excitable membranes, 2nd ed. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, Mass.

- 19.Jonas, D., I. Walev, T. Berger, M. Liebetrau, M. Palmer, and S. Bhakdi. 1994. Novel path to apoptosis: small transmembrane pores created by staphylococcal alpha-toxin in T lymphocytes evoke internucleosomal DNA degradations. Infect. Immun. 62:1304-1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knight, P. J. K., B. H. Knowles, and D. J. Ellar. 1995. Molecular cloning of an insect aminopeptidase N that serves as a receptor for Bacillus thuringiensis CryIA(c) toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 270:17765-17770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lear, J. D., J. P. Schneider, P. K. Kienker, and W. F. DeGrado. 1997. Electrostatic effects on ion selectivity and rectification in designed ion channel peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119:3212-3217. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, M. K., R. E. Milne, A. Z. Ge, and D. H. Dean. 1992. Location of a Bombyx mori receptor binding region on a Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 267:3115-3121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, J., J. Caroll, and D. J. Ellar. 1991. Crystal structure of insecticidal δ-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis at 2.5 Å resolution. Nature 353:815-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loeb, M. J., R. S. Hakim, P. Martin, N. Narang, S. Goto, and M. Takeda. 2000. Apoptosis in cultured midgut cells from Heliothis virescens larvae exposed to various conditions. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 45:12-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loeb, M. J., P. A. W. Martin, N. Narang, R. S. Hakim, S. Goto, and M. Takeda. 2001. Control of life, death, and differentiation in cultured midgut cells of the lepidopteran, Heliothis virescens. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Animal 37:348-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moar, W. J., M. Pusztai-Carey, H. van Faassen, D. Bosch, R. Frutos, C. Rang, K. Luo, and M. J. Adang. 1995. Development of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1C resistance by Spodoptera exigua (Hubner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2086-2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moellenbeck, D. J., M. L. Peters, J. W. Bing, J. R. Rouse, L. S. Higgins, L. Sims, T. Nevshemal, L. Marshall, R. T. Ellis, P. G. Bystrak, B. A. Lang, J. L. Stewart, K. Kouba, V. Sondag, V. Gustafson, K. Nour, D. Xu, J. Swenson, J. Zhang, T. Czapla, G. Schwab, S. Jayne, B. A. Stockhoff, K. Narva, H. E. Schnepf, S. J. Stelman, C. Poutre, M. Koziel, and N. Duck. 2001. Insecticidal proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis protect corn from corn rootworms. Nat. Biotechnol. 19:668-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagamatsu, Y., T. Koike, K. Sasaki, A. Yoshimoto, and Y. Furukawa. 1999. The cadherin-like protein is essential to specificity determination and cytotoxic action of the Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal Cry1Aa toxin. FEBS Lett. 460:385-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson, K. L., R. A. Brodsky, and J. T. Buckley. 1999. Channels formed by subnanomolar concentrations of the toxin aerolysin trigger apoptosis of T lymphomas. Cell Microbiol. 1:69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peyronnet, O., V. Vachon, J.-L. Schwartz, and R. Laprade. 2001. Ion channels induced in planar lipid bilayers by the Bacillus thuringiensis toxin Cry1Aa in the presence of gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar) brush border membrane. J. Membr. Biol. 184:45-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Purcell, J. P., J. T. Greenplate, M. G. Jennings, J. S. Ryerse, J. C. Pershing, S. R. Sims, M. J. Prinsen, D. R. Corbin, M. Tran, and R. J. Stonard. 1993. Cholesterol oxidase: a potent insecticidal protein active against boll weevil larvae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 196:1406-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rajamohan, F., O. Alzate, J. A. Cotrill, A. Curtiss, and D. H. Dean. 1996. Protein engineering of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin: mutations at domain II of Cry1Ab enhance receptor affinity and toxicity towards gypsy moth larvae. Proc. Acad. Natl. Sci. USA 93:14338-14343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajamohan, F., J. A. Cotrill, F. Gould, and D. H. Dean. 1996. Role of domain II, loop 2 residues of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ab δ-endotoxin in reversible and irreversible binding to Manduca sexta and Heliothis virescens. J. Biol. Chem. 271:2390-2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roush, R. T. 1997. Bt-transgenic crops: just another pretty insecticide or a chance for a new start in resistance management? Pest. Sci. 51:328-334. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saier, M. H., Jr. 2000. Families of proteins forming transmembrane channels. J. Membr. Biol. 175:165-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sangadala, S., F. S. Walters, L. H. English, and M. J. Adang. 1994. A mixture of Manduca sexta aminopeptidase and phosphatase enhances Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal Cry1A(c) toxin binding and 86Rb+-K+ efflux in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 269:10088-10092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schnepf, E., N. Crickmore, J. Van Rie, D. Lereclus, J. Baum, J. Feitelson, D. R. Ziegler, and D. H. Dean. 1998. Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:775-806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz, J.-L., Y.-J. Lu, P. Söhnlein, R. Brousseau, R. Laprade, L. Masson, and M. Adang. 1997. Ion channels formed in planar lipid bilayers by Bacillus thuringiensis toxins in the presence of Manduca sexta midgut receptors. FEBS Lett. 412:270-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Selvapandiyan, A., N. Arora, R. Rajagopal, S. K. Jalali, T. Venkatesan, S. P. Singh, and R. K. Bhatnagar. 2001. Toxicity analysis of N- and C-terminus-deleted vegetative insecticidal protein from Bacillus thuringiensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5855-5858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slatin, S. L., C. K. Abrams, and L. English. 1990. Delta-endotoxins form cation-selective channels in planar lipid bilayers. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 169:765-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vadlamidi, R. K., E. Weber, I. Ji, T. H. Ji, and L. A. Bullar, Jr. 1995. Cloning and expression of a receptor for an insecticidal toxin of Bacillus thuringiensis. J. Biol. Chem. 270:5490-5494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valaitis, A. P., M. K. Lee, F. Rajamohan, and D. H. Dean. 1995. Brush border membrane aminopeptidase-N in the midgut of the gypsy moth serves as the receptor for the Cry1Ac δ-endotoxin of Bacillus thuringiensis. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 25:1143-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valaitis, A. P., J. L. Jenkins, M. K. Lee, D. H. Dean, and K. J. Garner. 2001. Isolation and partial characterization of gypsy moth BTR-270, an anionic brush border membrane glycoconjugate that binds Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1A toxins with high affinity. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 46:186-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vanýsek, P. 1997. Activity coefficients of acids, bases, and salts, p. 5-95-5-96. In D. R. Lide (ed.), CRC handbook of chemistry and physics, 78th ed. CRC Press, New York, N.Y.

- 46.Warren, G. W. 1997. Vegetative insecticidal proteins: novel proteins for control of corn pests, p. 109-121. In N. Carozzi and M. Koziel (ed.), Advances in insect control. Taylor & Francis, Bristol, Pa.

- 47.Wolfersberger, M., P. Luthy, A. Maurer, P. Parenti, P. V. Sacchi, and B. Giordana. 1987. Preparation of brush border membrane vesicles (BBMV) from larval lepidopteran midgut. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 86A:301-308. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu, C.-G., M. A. Mullins, G. W. Warren, M. G. Koziel, and J. J. Estruch. 1997. The Bacillus thuringiensis vegetative insecticidal protein Vip3A lyses midgut epithelium cells of susceptible insects. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:532-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]