Abstract

The Tinto River (Huelva, southwestern Spain) is an extreme environment with a rather constant acidic pH along the entire river and a high concentration of heavy metals. The extreme conditions of the Tinto ecosystem are generated by the metabolic activity of chemolithotrophic microorganisms thriving in the rich complex sulfides of the Iberian Pyrite Belt. Molecular ecology techniques were used to analyze the diversity of this microbial community. The community's composition was studied by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) using 16S rRNA and by 16S rRNA gene amplification. A good correlation between the two approaches was found. Comparative sequence analysis of DGGE bands showed the presence of organisms related to Leptospirillum spp., Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, Acidiphilium spp., “Ferrimicrobium acidiphilum,” Ferroplasma acidiphilum, and Thermoplasma acidophilum. The different phylogenetic groups were quantified by fluorescent in situ hybridization with a set of rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes. More than 80% of the cells were affiliated with the domain Bacteria, with only a minor fraction corresponding to Archaea. Members of Leptospirillum ferrooxidans, Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, and Acidiphilium spp., all related to the iron cycle, accounted for most of the prokaryotic microorganisms detected. Different isolates of these microorganisms were obtained from the Tinto ecosystem, and their physiological properties were determined. Given the physicochemical characteristics of the habitat and the physiological properties and relative concentrations of the different prokaryotes found in the river, a model for the Tinto ecosystem based on the iron cycle is suggested.

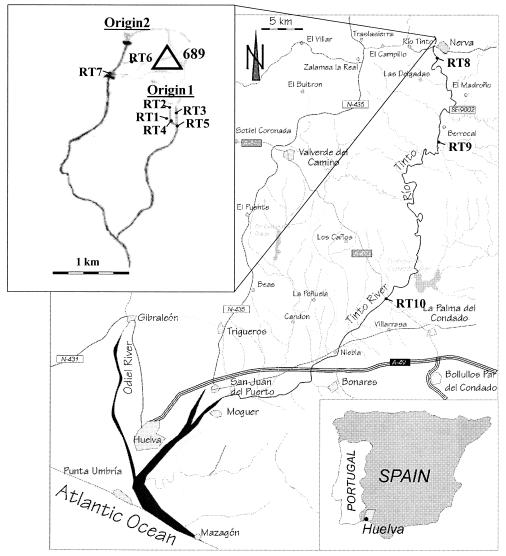

Microorganisms that are able to develop under extreme conditions have recently attracted considerable attention because of their peculiar physiology and ecology. These extremophiles also have important biotechnological applications (41, 44, 49, 51). Acidic environments are especially interesting because, in general, the low pH of the habitat is the consequence of microbial metabolism (24) and not a condition imposed by the system as is the case in many other extreme environments (temperature, ionic strength, high pH, radiation, pressure, etc.). The Tinto River, a 100-km-long river in southwestern Spain, is an example of such an extreme acidic ecosystem; it has a low pH (between 1.5 and 3.1) and high concentrations of heavy metals in solution (iron at 0.4 to 20.2 g/liter, copper at 0.02 to 0.70 g/liter, and zinc at 0.02 to 0.56 g/liter) (34). The river rises at Peña de Hierro, in the core of the Iberian Pyritic Belt, and flows into the Atlantic Ocean at Huelva (Fig. 1). It gives its name to an important mining region, which has been in operation for more than 5,000 years (20, 34).

FIG. 1.

Tinto River location, showing the sampling sites used in this work.

The Iberian Pyritic Belt is a 250-km-long geological entity that is embedded in the South Portuguese geotectonic zone of the Iberian Peninsula. Massive bodies of iron and copper sulfides constitute the main mineral ores (7). The basin of the Tinto River covers an area of around 1,700 km2, and its gentle slope facilitates the presence of a dense microbial community on the riverbed. The river is subject to a Mediterranean type water regime, and its flow is variable depending on the season. The highest flow values are reached during the winter, and the lowest are present during the summer (34). The pH remains low and constant regardless of the river flow. This is the result of the buffer effect produced by high concentrations of ferric iron along the river (24).

The extreme conditions of the Tinto River are the product of the metabolic activity of chemolithotrophic microorganisms thriving in its water and not, as formerly believed, the result of the intensive mining activity carried out in the area (15, 19, 33, 56). Analysis of massive laminated iron bioformations corresponding to old terraces of the river has shown that they predate the oldest mining activity reported in the area and are similar to the laminar structures that are being formed currently in the river (20, 24).

The extremely low pH of the river and the high concentrations of sulfates, ferric iron, and other heavy metals make it equivalent to a natural acidic mine drainage system (AMD) (26, 27, 29). Thus, the results of conventional microbiological studies showing that both sulfur- and iron-oxidizing bacteria—such as Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (formerly Thiobacillus ferrooxidans) and Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans—were present in rather high numbers along the river were not surprising (34). Moreover, an unexpected level of eukaryotic diversity has been described in the Tinto River in spite of the extreme conditions found in its waters (3, 34).

Classical microbial ecology analysis is limited by the unavoidable need for isolation of the microorganisms prior to their characterization (2). Furthermore, acidophilic chemolithotrophs are not easy to grow, especially in solid media (26, 28). Since its isolation in the late 1940s, Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans has been considered principally responsible for the extreme conditions of AMD systems (11). However, recent molecular ecology studies have shown that other iron-oxidizing microorganisms, e.g., Leptospirillum spp. and Ferroplasma spp., might be more important than Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans in the generation of acidic environments (16, 23, 48, 52, 54).

The introduction of molecular biology techniques, such as fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE), and cloning, has produced significant advances in the field of microbial ecology (1, 2). In this report we present an in-depth characterization of the microbial diversity and composition of the Tinto River ecosystem. The combination of classical isolation and molecular ecology methods provides sufficient information about the microbiology of the Tinto River to advance a geomicrobiological model for this unique ecosystem.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Physicochemical parameters.

Conductivity, pH, redox potential, and oxygen concentration were measured in situ by using specific electrodes. Redox potential and pH were measured with a Crison 506 pH/Eh meter, and conductivity was measured with an Orion-122 conductivity-meter. Oxygen concentration and water temperature were determined with an Orion-810 oxymeter. Heavy metal concentrations were determined using X-ray fluorescence reflection (TXRF) and inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS; Universidad Autónoma de Madrid [UAM] Scientific Service). Sulfate concentrations were determined by a turbidimetric method (31).

Microorganisms.

The prokaryotic strains used to evaluate the specificities of the newly designed hybridization probes were Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans DSM9465, Leptospirillum ferrooxidans DSM2391 and DSM2705, Acidiphilium cryptum DSM2389, Acidimicrobium ferrooxidans DSM10331, Caulobacter fusiformis DSM4728, Sphingomonas trueperi DSM7225, Acidomonas methanolica DSM5432, Thermoplasma acidophilum DSM1728, and Ferroplasma acidiphilum DSM12658.

Sample collection.

Samples were collected from various sampling stations along the Tinto River (Fig. 1) in June 1999, October 1999, and May 2000. Samples for DNA extraction were collected in 1-liter bottles and kept on ice until they were filtered through a Millex-GS Millipore filter (pore size, 0.22 μm; diameter, 50 mm). The filters were stored at −20°C until processing. Samples for FISH were immediately fixed with minimal Mackintosh medium [0.132 g of (NH4)2SO4, 0.027 g of KH2PO4, 0.053 g of MgCl2 · 6H2O, 0.147 g of CaCl2 · 2H2O, pH 1.8] with 4% formaldehyde and were kept on ice for 2 to 4 h (37). The fixed samples were filtered through GTTP 025 Millipore filters (pore size, 0.22 μm). Samples were washed with 10 ml of minimal Mackintosh medium (pH 1.5) to eliminate excess formaldehyde and heavy metals, followed by a 10-ml wash with phosphate-buffered saline (130 mM NaCl-10 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.2]). Filters were stored at −20°C prior to hybridization.

Total DNA and RNA extraction.

Each Millex-GS Millipore filter was cut and treated with 2 ml of SET buffer (25% saccharose-50 mM Tris [pH 8]-2 mM EDTA) overnight at −20°C in a 15-ml Falcon tube. After the sample was thawed, 120 μl of sodium dodecyl sulfate (25%) and 2.8 U of pronase (Boehringer Mannheim) were added, and the mixture was incubated at 4°C for 30 min. Protein precipitation with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and 0.5 ml of sodium acetate (2 M; pH 5.2) was repeated until protein was completely eliminated from the interface. Nucleic acids were precipitated overnight by addition of 2.5 volumes of ice-cold ethanol (96%) at −20°C. Nucleic acids were pelleted by centrifugation, washed with 70% ethanol, vacuum dried, and resuspended in Milli-Q water.

PCR amplification, DGGE, and sequencing.

PCR amplification of 16S rRNA gene fragments between Escherichia coli positions 344 and 915 for the domain Archaea (47, 55) and between E. coli positions 341 and 907 for the domain Bacteria (42), reverse transcription of 16S rRNA and amplification of the 16S rRNA gene, DGGE, excision of bands, and reamplification were performed as previously described (42). All primers used in this work are listed in Table 1. The Taq Dideoxy Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) was used to sequence the 16S rRNA gene fragments. Sequencing reactions were run on an Applied Biosystems 373S DNA sequencer.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for PCR amplification

| Primera | Target siteb | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Specificity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 341F-GCc | 341-357 | CCT ACG GGA GGC AGC AG | Most Bacteria | 42 |

| 907RM | 907-926 | CCG TCA ATT CMT TTG AGT TT | Most known organisms | 42 |

| ARC344F-GC | 344-363 | ACG GGG YGC AGC AGG CGC GA | Most Archaea | 47 |

| ARC915R | 915-934 | GTG CTC CCC CGC CAA TTC CT | Most Archaea | 55 |

| CYA359F-GC | 359-378 | GGG GAA TYT TCC GCA ATG GG | Cyanobacteria and chloroplasts | 46 |

| CYA781R(a)d | 781-805 | GAC TAC TGG GGT ATC TAA TCC CATT | Cyanobacteria and chloroplasts | 46 |

| CYA781R(b)d | 781-805 | GAC TAC AGG GGT ATC TAA TCC CTTT | Cyanobacteria and chloroplasts | 46 |

F (foward) and R (reverse) indicate the orientations of the primers in relation to the rRNA.

Positions are given according to the E. coli numbering of Brosius et al. (10).

GC is a 40-nucleotide GC-rich sequence attached to the 5′ end of the primer. The GC sequence is 5′-CGC CCG CCG CGC CCC GCG CCC GTC CCG CCG CCC CCG CCC-3′.

Reverse primer CYA781R is an equimolar mixture of CYA781R(a) and CYA781R(b).

New partial sequences were added to an alignment of about 15,000 homologous 16S rRNA primary structures (38) by using the aligning tool of the ARB package (http://www.mikro.biologie.tu-muenchen.de). Aligned sequences were inserted within a stable tree by using the ARB parsimony tool, which enables reliable positioning of new sequences without alignment (36).

Phylogenetic analysis.

Sequences of DGGE bands and 16S rRNA gene clones were initially compared with reference sequences contained in the EMBL nucleotide sequence database by using the BLAST program and were subsequently aligned with 16S rRNA reference sequences in the ARB package (http://www.mikro.biologie.tu-muenchen.de). DGGE partial-sequence dendrograms were obtained by using the DNAPARS parsimony tool included in the ARB software.

Cell counts, FISH, and oligonucleotide probe design.

Hybridization and microscopy counting of hybridized and 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-stained cells were performed as described previously (2). Means were calculated by using 10 to 20 randomly chosen fields for each filter section, which corresponded to 800 to 1,000 DAPI-stained cells. Counting results were corrected by subtracting signals observed with the control probe NON338. Probes used in this work are listed in Table 2. Oligonucleotide probes ACT465a, ACT465b, ACT465c, ACT465d, ACM1160, ACD638, LEP154, LEP432, LEP439, LEP488, LEP636, and TMP654 were designed by using the PROBE_FUNCTION tool of the ARB package. Cy3-labeled probes were synthesized by Interactiva (Ulm, Germany) and Qiagen (Barcelona, Spain). The specificities of newly designed probes were evaluated with the PROBE_MATCH tool of the ARB package and by hybridization with pure cultures. Hybridization conditions were optimized by using different formamide concentrations (2).

TABLE 2.

Fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes used for in situ hybridization experiments

| Probe | Target | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | % FMa | Specificity | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUB338 | 16S | GCT GCC TCC CGT AGG AGT | 35 | Bacteria domain | 1 |

| ALF968 | 16S | GGT AAG GTT CTG CGC GTT | 20 | α-Proteobacteria | 43 |

| ACD638 | 16S | CTC AAG ACA ACA CGT CTC | 20 | Acidiphilium spp. | This work |

| BET42a | 23S | GCC TTC CCA CTT CGT TT | 35 | β-Proteobacteria | 39 |

| GAM42a | 23S | GCC TTC CCA CAT CGT TT | 35 | γ-Proteobacteria | 39 |

| THIO1 | 16S | GCG CTT TCT GGG GTC TGC | 35 | Group a Acidithiobacillus spp. | M. Stoffels, unpublished data |

| ACT465a | 16S | GTC AAC AGC AGC TCG TAT | 20 | Group b Acidithiobacillus spp. | This work |

| ACT465b | 16S | GTC AAC AGC AGA TCG TAT | 10 | Group c Acidithiobacillus spp. | This work |

| ACT465c | 16S | GTC AAC AGC AGA TTG TAT | 10 | Group d Acidithiobacillus spp. | This work |

| ACT465d | 16S | GTC AAT AGC AGA TTG TAT | 10 | Acidithiobacillus spp. | This work |

| NTR712b | 16S | CGC CTT CGC CAC CGG CCT TCC | 35 | Nitrospira group | 14 |

| LEP154 | 16S | TTG CCC CCC CTT TCG GAG | 35 | Leptospirillum ferriphilum | This work |

| LEP634 | 16S | AGT CTC CCA GTC TCC TTG | 40 | Group a Leptospirillum spp. | This work |

| LEP636 | 16S | CCA GCC TGC CAG TCT CTT | 35 | Group c Leptospirillum ferrooxidans | This work |

| LEP439 | 16S | CCT TTT TCG TCC CGT GCA | 35 | Group c1 Leptospirillum ferrooxidans | This work |

| LEP432 | 16S | CGT CCC GAG TAA AAG TGG | 20 | Group c2 Leptospirillum ferrooxidans | This work |

| SRB385 | 16S | CGG CGT CGC TGC GTC AGG | 35 | δ-Proteobacteria | 1 |

| DSS658 | 16S | TCC ACT TCC CTC TCC CAT | 60 | Desulfosarcina, Desulfococcus, Desulfofrigus | 40 |

| DSV698 | 16S | GTT CCT CCA GAT ATC TAC GG | 35 | Desulfovibrio spp. | 40 |

| ACM1160 | 16S | CCT CCG AAT TAA CTC CGG | 35 | Acidimicrobium spp. | This work |

| ARCH915 | 16S | GTG CTC CCC CGC CAA TTC CT | 20 | Archaea domain | 55 |

| FER656 | 16S | CGT TTA ACC TCA CCC GAT C | 35 | Ferroplasma spp. | 16 |

| TMP654 | 16S | TTC AAC CTC ATT TGG TCC | 35 | Thermoplasma spp., Picrophilus spp. | This work |

| NON338 | ACT CCT ACG GGA GGC AGC | 35 | Negative control | 1 |

Percent (vol/vol) formamide in the hybridization buffer.

The name of this probe in the work of Daims et al. (14) is S-*-tspa-0712-a-A-21.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AJ517306 to AJ517313, AJ517353 to AJ517364, and AJ517430 to AJ517447.

RESULTS

Physicochemical parameters.

Mean pHs and redox potentials obtained at the different sampling sites over the 2 years of this study are shown in Table 3. The pH was rather constant along the river (mean, 2.4) with the exception of station RT3, where the pH was always higher (mean, 4.7), probably due to the lack of iron in solution to buffer the system. The redox potential was high and relatively constant along the river, between +420 and +608 mV, except for station RT3, where it was always lower. The total concentrations of metals reaching higher concentrations in the Tinto ecosystem, Fe, Cu, and Zn, are shown in Table 3. Means were 4.9 g/liter for Fe, 25.7 ppm for Cu, and 86.6 ppm for Zn. A mean concentration of 9.2 g/liter was found for sulfate. In general, the concentrations of Fe and sulfate were higher in the upper part of the river. However, the Cu and Zn concentrations were highest at sampling station RT9, at 100 and 340 ppm, respectively. Dissolved-oxygen levels were different at different sampling stations depending on the hydrological regime of the river (20, 34). Anoxic conditions were found at the bottoms of several sampling stations (RT7, RT9, and RT10), precluding the existence of an oxygen gradient in the water column at these sites. For complementary information concerning physicochemical parameters measured in the Tinto ecosystem, see the work of López-Archilla et al. (34).

TABLE 3.

Physicochemical characterization of sampling sites

| Sampling site | pH (mean ± SD) | Mean Eh ± SD (mV) | Mean metal concn ± SD (ppm)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO42− | Fe | Cu | Zn | |||

| RT1 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 563 ± 63 | 27,191 ± 157 | 20,231 ± 23 | 22 ± 2 | 25 ± 1 |

| RT2 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 421 ± 54 | 12,061 ± 66 | 632 ± 3 | NDa | 22 ± 0.4 |

| RT3 | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 246 ± 30 | 1,853 ± 9 | 334 ± 1 | ND | 24 ± 0.3 |

| RT4 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 513 ± 33 | 15,636 ± 82 | 9,680 ± 10 | 10 ± 0.5 | 27 ± 1 |

| RT5 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 490 ± 30 | 5,412 ± 38 | 2,298 ± 4 | 2 ± 0.1 | 25 ± 0.3 |

| RT6 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 460 ± 42 | —b | — | — | — |

| RT7 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 538 ± 55 | 3,756 ± 31 | 1,837 ± 4 | 27 ± 0.4 | 97 ± 1 |

| RT8 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 420 ± 1 | — | — | — | — |

| RT9 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 494 ± 43 | 4,836 ± 39 | 3,018 ± 5 | 100 ± 1 | 340 ± 1 |

| RT10 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 608 ± 37 | 2,665 ± 28 | 853 ± 3 | 45 ± 0.5 | 139 ± 1 |

ND, not detected.

—, not measured.

DGGE fingerprint analyses.

To evaluate the level of microbial diversity, DGGE analyses were performed with samples obtained from different sampling stations along the river (Fig. 1). In this study both RNA and DNA were used to obtain DGGE fingerprints in order to facilitate their comparison with the results obtained by other techniques.

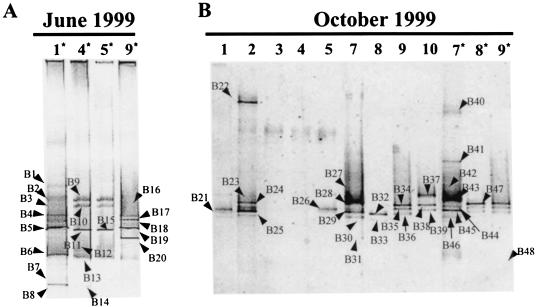

By using primer sets for Bacteria, Archaea, and oxygenic phototrophs, partial 16S rRNA genes were amplified from different locations along the river. Amplification of the 16S rRNA gene with bacterial primers was successful in all samples. In the case of oxygenic phototrophs, amplification was obtained only for samples RT1, RT4, RT5, and RT9 from June 1999. With archaeal primers, PCR products were obtained from all the samples from June 1999 but only from four samples from October 1999 (RT7, RT8, RT9, and RT10).

The amplifications resulted in reproducible DGGE fingerprints with a relatively small number of bands (Fig. 2). In general, the number of amplified bands obtained with bacterial primers was higher in samples from stations with less extreme conditions than in those from the river's origin. By amplification with primers specific for oxygenic phototrophs, a very clear band was detected in each sample (data not shown). However, four bands were found for the RT1 sample. In the case of Archaea, two bands were obtained in most of the samples, except for that from station RT5, where three bands were detected, two of which had electrophoretic mobilities different from that of the rest of the samples. In the October 1999 samples, only one band was detected, always with the same electrophoretic mobility. Generally, the number of bands was greater in the June 1999 samples than in the October 1999 samples (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

DGGE fingerprints of 16S rRNA and reverse-transcribed 16S rRNA (marked by asterisks) obtained by using universal primers for members of the domain Bacteria. (A) Samples from June 1999; (B) samples from October 1999. Lane numbers correspond to sampling sites. Arrows label different bands.

Phylogenetic affiliation of sequences retrieved from DGGE bands.

Most bands (around 80) were excised from the DGGE fingerprints, reamplified, purified, and sequenced. A total of 57 bands yielded sequences that were identified by using the BLAST program and the ARB package. The rest of the bands either did not yield a reamplification product or yielded a product whose sequence had too many ambiguous positions to be identified.

Table 4 lists the bands together with the closest identified microorganisms (sequence similarity, ≥98%). All of these microorganisms had been detected in previous studies of the Tinto River (34) and in different AMD systems. Furthermore, all of them were also detected by hybridization (FISH) in this work (see below). Most of the bacteria identified corresponded to three different genera: Acidithiobacillus, Leptospirillum, and Acidiphilium. Only two bands (B8 and B14) were assigned to a different genus: “Ferrimicrobium acidiphilum.” This gram-positive bacterium has also been identified in AMD systems (4, 6, 9, 26).

TABLE 4.

DGGE bands and the closest relative microorganisms with an rRNA gene or rRNA sequence identity of ≥98%a

| Phylogenetic group | Band | DNA or RNAb | Related sequence | % Similarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ-Proteobacteria | B4 | RNA | Acidithiobacillus sp. strain NO-37 | 98 |

| B5 | RNA | Acidithiobacillus sp. strain NO-37 | 99 | |

| B11 | RNA | Acidithiobacillus sp. strain NO-37 | 98 | |

| B16 | RNA | Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans D2 | 98 | |

| B17 | RNA | Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans D2 | 99 | |

| B18 | RNA | Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans D2 | 98 | |

| B20 | RNA | Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans D2 | 98 | |

| B34 | DNA | Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans D2 | 99 | |

| B35 | DNA | Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans D2 | 99 | |

| B36 | DNA | Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans K2 | 99 | |

| Nitrospira | B6 | RNA | Leptospirillum ferrooxidans DSM2705 | 99 |

| B27 | DNA | Uncultured bacterium TRA1-10 | 99 | |

| B28 | DNA | Uncultured bacterium TRA1-10 | 98 | |

| B42 | RNA | Uncultured bacterium TRA1-10 | 99 | |

| B43 | RNA | Uncultured bacterium TRA1-10 | 99 | |

| B37 | DNA | Uncultured bacterium TRA1-10 | 99 | |

| α-Proteobacteria | B23 | DNA | Acidiphilium sp. strain MBIC4287 | 99 |

| B24 | DNA | Acidiphilium sp. strain MBIC4287 | 98 | |

| B25 | DNA | Acidiphilium sp. strain MBIC4287 | 98 | |

| B29 | DNA | Acidiphilium sp. strain MBIC4287 | 98 | |

| B31 | DNA | Uncultured bacterium TRB3 | 99 | |

| B32 | DNA | Acidiphilium sp. strain MBIC4287 | 99 | |

| B38 | DNA | Acidiphilium sp. strain MBIC4287 | 99 | |

| B45 | RNA | Acidiphilium sp. strain MBIC4287 | 99 | |

| B47 | RNA | Acidiphilium sp. strain MBIC4287 | 99 | |

| B48 | RNA | Acidiphilium sp. strain MBIC4287 | 99 | |

| Actinobacteria | B8 | RNA | “Ferrimicrobium acidiphilum” | 99 |

| B14 | RNA | “Ferrimicrobium acidiphilum” | 99 | |

| Thermoplasmata | A7 | RNA | Ferroplasma acidiphilum | 99 |

| A9 | DNA | Ferroplasma acidiphilum | 99 |

Species level similarity.

RNA or DNA sample.

The primers for oxygenic phototrophs were designed to detect both cyanobacteria and algal chloroplasts (46). In this study, three sequences were assigned clearly to cyanobacteria (data not shown). The closest relatives for these sequences were Stanieria cyanosphaera (93% similarity) and Cyanobacterium sp. (91% similarity) (25). Until now no cyanobacteria had been found in acidic environments. Furthermore, the general consensus had been that cyanobacteria could not grow at an acidic pH. We were unable to detect cyanobacteria by epifluorescence microscopy or to isolate them in specific media, but the sequence retrieved from these bands suggests the possible existence of cyanobacteria in the Tinto ecosystem.

The bands corresponding to Archaea were assigned to the Thermoplasmata class, namely, Thermoplasma acidophilum (A8, with a homology of 89%) and Ferroplasma acidiphilum (A1, A3, and A7, with homologies of 96, 97, and 99%, respectively). In the October 1999 samples, only one band was detected, and it was classified as Ferroplasma (A9, with 99% homology). This result agrees with the FISH results (see below) and previous studies on AMD systems (16, 17).

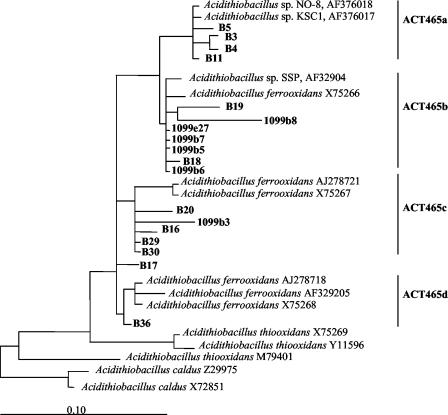

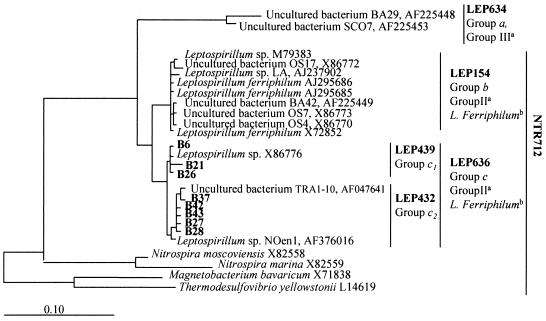

The phylogenetic affiliations within the genus Acidithiobacillus and the Nitrospira phylum are shown in Fig. 3 and 4. In the case of Acidithiobacillus, all the amplified sequences were related to Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. They clustered into four groups: a, b, c, and d (Fig. 3). With respect to the Nitrospira phylum, all the sequences retrieved clustered with Leptospirillum sp. strains. Figure 4 shows a dendrogram with the relative positions of the Leptospirillum sequences. Three different clusters can be observed: groups a, b, and c. All DGGE sequences retrieved from the Tinto River fell into group c and were distributed into two subgroups, namely, c1 and c2. Probes specific for groups a, b, c, c1, and c2 were designed (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic affiliations of DGGE sequences with strong similarities to Acidithiobacillus spp. The tree is based in a parsimony analysis that includes only complete or almost-complete sequences of representative bacteria (38). The topology of the tree resulted from insertion of the partial DGGE sequences without modifying its topology during sequence positioning (ARB software [http://www.mikro.biologie.tu-muenchen.de]). Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans sequences grouped into four clusters: a, b, c, and d. Sequences retrieved from DGGE bands are designated by the letter B followed by the number of the band. The specificities of the four probes designed to identify each group are shown.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic affiliations of DGGE sequences with strong similarities to Leptospirillum spp. The tree was constructed as described in the legend to Fig. 3. Leptospirillum spp. grouped into three clusters: a, b (L. ferriphilum), and c (L. ferrooxidans). Sequences from group c are distributed into two subgroups named c1 and c2. All the DGGE sequences from the Tinto River fall into group c. The specificities of the probes (LEP634, LEP154, LEP636, LEP439, and LEP432) designed to identify members of the different groups are shown. The specificity of probe NTR712 (specific for members of the Nitrospira phylum with the exception of group a of leptospirilli) is also shown. a, Groups defined by Bond et al. (6); b, species defined by Coram and Rawlings (12).

FISH and total cell counts.

Total cell counts were determined by DAPI staining. The number of cells found was 105 to 107 per ml, regardless of the station and season. Only sample RT7 from June 1999 and sample RT9 throughout the period studied showed higher cell numbers (Table 5). Most of the DAPI-stained cells (range, 43% [RT10, June 1999] to 92% [RT1, October 1999]; mean, 78% of total cell counts) hybridized with the bacterial probe EUB338. Recently, it was shown that the bacterial probe EUB338 does not detect all members of the domain Bacteria (13). Some bacterial phyla, most notably the Planctomycetales and Verrucomicrobia, do not hybridize with this probe. Consequently, total bacterial numbers monitored in this study could have been underestimated. Very few Archaea were found in the river; e.g., in the May 2000 sampling, only 3% of the total cell count could be assigned to this domain.

TABLE 5.

DAPI and FISH counts with bacterial-, group-, and species-specific probes

| Sampling site and date (mo yr) | Total cell counts (105 ml−1) | Fraction (%) of cells detected with probea:

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUB338 | ALF968 | ACD638 | BET42a | GAM42a | THIO1 | ACT465a | ACT465b | ACT465c | ACT465d | NTR712 | LEP634 | LEP154 | LEP636 | LEP439 | LEP432 | ACM1160 | TMP654 | FER656 | ||

| RT1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Oct. 99 | 14 ± 5 | 92 ± 2 | 2 ± 0.3 | BDLb | BDL | 52 ± 1 | 51 ± 2 | 45 ± 2 | BDL | BDL | BDL | 40 ± 1 | 3 ± 0.3 | 6 ± 1 | 32 ± 1 | 28 ± 1 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| May 00 | 5 ± 1 | 81 ± 1 | BDL | BDL | BDL | 21 ± 1 | 21 ± 5 | 33 ± 1 | BDL | BDL | BDL | 55 ± 1 | 2 ± 0.3 | 5 ± 0.4 | 37 ± 0.3 | 38 ± 1 | BDL | BDL | BDL | 2 ± 1 |

| RT2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Oct. 99 | 4 ± 2 | 81 ± 4 | 55 ± 2 | 42 ± 2 | BDL | <1 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | 2 ± 0.2 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| May 00 | 3 ± 1 | 74 ± 1 | 3 ± 0.1 | BDL | 35 ± 0.4 | 1 ± 0.1 | 2 ± 0.1 | 1 ± 0.1 | BDL | 1 ± 0.2 | BDL | 3 ± 0.1 | 1 ± 0.1 | BDL | 9 ± 0.5 | 1 ± 0.1 | 3 ± 0.2 | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| RT3 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Oct. 99 | 16 ± 6 | 84 ± 2 | 2 ± 0.2 | BDL | 81 ± 2 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | 1 ± 0.3 | BDL | BDL |

| May 00 | 4 ± 1 | 83 ± 1 | BDL | BDL | 64 ± 1 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | 1 ± 0.3 | BDL | BDL |

| RT4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Oct. 99 | 7 ± 3 | 89 ± 2 | 16 ± 1 | 11 ± 1 | 8 ± 0.5 | 39 ± 2 | 25 ± 1 | 21 ± 1 | 2 ± 0.2 | BDL | BDL | 30 ± 1 | BDL | 1 ± 0.2 | 35 ± 1 | 35 ± 1 | BDL | 4 ± 1 | BDL | BDL |

| May 00 | 14 ± 3 | 78 ± 3 | BDL | BDL | 2 ± 0.1 | 3 ± 0.3 | BDL | 1 ± 0.3 | BDL | BDL | BDL | 42 ± 2 | 2 ± 0.1 | BDL | 34 ± 1 | 5 ± 0.5 | 33 ± 0.2 | BDL | <1 | <1 |

| RT5 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Oct. 99 | 3 ± 1 | 85 ± 2 | 17 ± 1 | 18 ± 1 | BDL | 35 ± 2 | 20 ± 1 | 19 ± 1 | 2 ± 0.3 | BDL | BDL | 22 ± 1 | BDL | 1 ± 0.3 | 33 ± 1 | 20 ± 1 | BDL | 5 ± 1 | BDL | BDL |

| May 00 | 14 ± 3 | 81 ± 1 | BDL | BDL | 4 ± 0.2 | 3 ± 0.1 | BDL | 3 ± 0.3 | BDL | 1 ± 0.1 | BDL | 51 ± 1 | BDL | 1 ± 0.1 | 59 ± 1 | 8 ± 0.5 | 43 ± 1 | BDL | <1 | <1 |

| RT6 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Oct. 99 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| May 00 | 13 ± 4 | 83 ± 1 | 1 ± 0.1 | BDL | BDL | 48 ± 1 | 50 ± 1 | 46 ± 3 | 12 ± 1 | 29 ± 1 | <1 | 21 ± 0.5 | <1 | 1 ± 0.1 | 9 ± 0.3 | 7 ± 0.3 | <1 | 1 ± 0.3 | BDL | 2 ± 0.2 |

| RT7 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Oct. 99 | 65 ± 10 | 77 ± 1 | 27 ± 1 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | 50 ± 1 | 2 ± 0.1 | BDL | 47 ± 1 | 3 ± 0.2 | 52 ± 1 | 3 ± 0.3 | BDL | BDL |

| May 00 | 82 ± 12 | 85 ± 1 | <1 | <1 | 1 ± 0.1 | 69 ± 0.1 | 70 ± 2 | 1 ± 0.1 | 46 ± 1 | 29 ± 0.4 | 2 ± 0.3 | 7 ± 0.4 | <1 | BDL | 8 ± 0.5 | 2 ± 0.1 | 5 ± 0.3 | <1 | <1 | BDL |

| RT8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Oct. 99 | 45 ± 10 | 80 ± 1 | 20 ± 0.4 | 19 ± 1 | 5 ± 1 | 35 ± 1 | 35 ± 1 | 3 ± 0.2 | 10 ± 0.3 | 6 ± 0.3 | BDL | 7 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | BDL | 3 ± 0.2 | BDL | 0.4 ± 0.1 | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| May 00 | 5 ± 1 | 77 ± 1 | 15 ± 0.3 | 14 ± 0.4 | 3 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 | 15 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 8 ± 0.4 | 6 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 0.8 | 4 ± 0.2 | 1 ± 0.1 | <1 | 5 ± 0.2 | 3 ± 0.2 | 1 ± 0.1 | BDL | <1 | 3 ± 0.1 |

| RT9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Oct. 99 | 150 ± 17 | 85 ± 1 | 16 ± 1 | 2 ± 0.2 | BDL | 59 ± 1 | 73 ± 2 | <1 | 26 ± 0.5 | 14 ± 1 | <1 | 1 ± 0.1 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| May 00 | 140 ± 19 | 85 ± 1 | BDL | BDL | BDL | 64 ± 1 | 70 ± 1 | 12 ± 1 | 56 ± 1 | 10 ± 0.3 | <1 | 19 ± 0.4 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| RT10 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Oct. 99 | 16 ± 5 | 86 ± 1 | 28 ± 0.6 | 13 ± 1 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | 1 ± 0.1 | BDL | BDL | 65 ± 1 | BDL | BDL | 69 ± 1 | BDL | 64 ± 1 | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| May 00 | 9 ± 2 | 83 ± 1 | 8 ± 0.2 | 13 ± 0.5 | 72 ± 1 | <1 | <1 | BDL | BDL | <1 | BDL | <1 | BDL | <1 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL |

Percent detection compared to detection of all DAPI-stained cells. ND, not done.

BDL, below detected limit (<0.1).

FISH counts using group- and species-specific probes.

By using four group-specific probes, around 68% of the cells detected with EUB338 could be assigned (Table 5). The most abundant phylogenetic groups in the Tinto River corresponded to the γ-Proteobacteria and the Nitrospira phylum (Table 5).

The percentage of DAPI-stained cells that hybridized with GAM42a (a 23S rRNA-targeted probe), complementary to a signature sequence present in most members of the γ-Proteobacteria, ranged from 0 to 69% depending on the sampling site (Table 5). The cells identified with this probe showed two different morphologies: a group of long rods in short chains and a group of single rods. Previous studies showed Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans and Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans to be the most common γ-proteobacteria in this system (34); thus, a THIO1 probe, specific for the Acidithiobacillus genus, was used in the last two samplings (October 1999 and May 2000). The yields for THIO1 and GAM42a were very similar in each sample. All the γ-proteobacteria detected by DGGE showed high homology to Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, so four complementary probes designed for this species were used for further analysis (Fig. 5). The four probes showed positive results for the different samples (Table 5). Group a of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans was most abundant, up to 45% of DAPI-stained cells, at the Origin 1 section of the river (Fig. 1). At Origin 2, as well as in the middle course of the river, all four groups were present. Levels for group d were low at all the stations. In most cases, the total number of cells detected with the four Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans-specific probes was similar to those detected with the GAM42a and THIO1 probes.

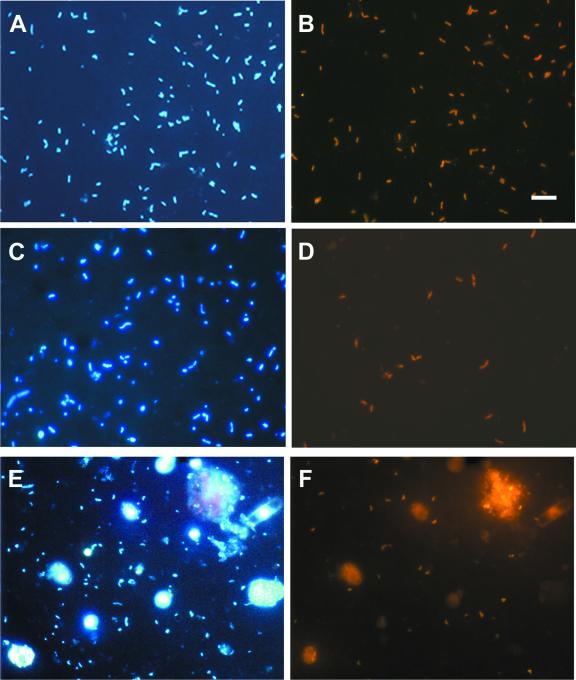

FIG. 5.

Epifluorescence micrographs of bacteria from the Tinto River. (A, C, and E) DAPI-stained cells in RT9, RT1, and RT10 samples, respectively; (B, D, and F) same fields as A, C, and E, respectively, showing cells hybridized with different specific probes. Samples were hybridized with probe ACT465c (Cy3 labeled), specific for group c of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (B), probe ACD638 (Cy3 labeled), specific for Acidiphilium spp. (D), or probe LEP636 (Cy3 labeled), specific for group c of leptospirilli (F). Bars, 5 μm.

The percentage of DAPI-stained cells hybridizing with the NTR712 probe, targeted to members of the Nitrospira phylum, reached 65%. Vibrioid morphologies and occasional spirals were the shapes identified with this probe. The Nitrospira phylum encompasses three major genera: Nitrospira, Magnetobacterium, and Leptospirillum. Morphological, physiologic, and metabolic studies of these genera and former studies on the Tinto system suggested that Leptospirillum is the genus most likely to be present in the Tinto River samples (18, 22, 34). Five probes designed for the different phylogenetic groups defined for Leptospirillum spp. were used in the hybridization experiments (Fig. 5), and all of them gave positive hybridization results (Table 5). The lowest counts were obtained with probes LEP634 and LEP154 (specific for Leptospirillum ferriphilum). The most representative group all along the river was c, detected with probe LEP636 (specific for L. ferrooxidans). At Origin 1, group c1 (probe LEP439) was well represented, while at Origin 2, group c2 dominated (probe LEP432). Overall, the total cell count detected with Leptospirillum-specific probes was lower than that detected with the NTR712 probe (Nitrospira phylum-specific probe), and the total cell counts detected with probes LEP439 (group c1) and LEP432 (group c2) were equivalent to the percentage observed with probe LEP636 (group c).

The third most abundant group in the Tinto ecosystem corresponded to α-Proteobacteria. The ALF968 probe was used to detect this group of bacteria. The percentage of DAPI-stained cells hybridizing with this probe reached 51%. Previous studies identified the genus Acidiphilium as the most probable α-proteobacterial candidate for this type of environment (34). Probe ACD638, designed to identify members of the species Acidiphilium organovorum, Acidiphilium multivorum, and Acidiphilium cryptum, was used to quantify this population (Table 5). The percentage of positive hybridizations obtained with this probe was similar in most samples to that obtained with the ALF968 probe, except for RT7 and RT9, where the Acidiphilium count was lower than that with the ALF968 probe.

Members of the β-Proteobacteria were detected with probe BET42a (a 23S rRNA-targeted probe). This group of bacteria represented a minority in all samples from all stations except for RT3, where it was determined to constitute 73% (mean) of the total cell count. For detection of two other genera that are characteristic in AMD systems, “Ferrimicrobium” and the related Acidimicrobium, probe ACM1160 was designed. These actinobacteria were found at rather low percentages in all samples, up to 5% (Table 5).

Three probes specific for sulfate-reducing bacteria were used: SRB385, DSS658, and DSV698. This type of bacterium had not been reported before in the Tinto ecosystem. When these probes were used, positive hybridization signals were detected at the RT8 station for the October 1999 and May 2000 samplings (data not shown).

Probes FER656 (16), specific for the genus Ferroplasma, and TMP654, specific for the genus Thermoplasma, were used for the detection of members of the Archaea domain in this ecosystem. Members of the archaeal genera Ferroplasma (strict iron-oxidizing chemolithotrophs) and Thermoplasma (facultatively aerobic heterotrophs, with anaerobic growth enhanced by elemental sulfur) within the Thermoplasmata class (23) are common in some AMD systems (6, 16). Ferroplasma and Thermoplasma cells were detected at low counts (means, 2% of DAPI-stained cells for Ferroplasma and <1% for Thermoplasma) only in the May 2000 sampling.

DISCUSSION

Many conventional microbial ecology studies have been performed on AMD systems, since the acidophilic microbes growing in these systems have important biotechnological applications (26, 27, 34, 45, 52). However, few studies to date have used molecular approaches to examine the microbial diversity of these habitats (5, 6, 21, 54, 57). Furthermore, few molecular ecology studies have been performed in rivers (32), probably due to their complexity. One of the aims of this work was to compare the results obtained by using conventional and molecular ecology techniques for the microbial characterization of an extreme acidic river.

The use of molecular ecological techniques for the study of a complex system such as the Tinto River should allow a better quantification of the different microbial populations. In order to account for intrinsic methodological limitations, and to increase the significance of the results, two complementary methods were used in this study: DGGE and FISH. The results obtained proved that both methodologies are appropriate for a system such as the Tinto River and both provide an accurate description of its prokaryotic diversity.

Total cell counts measured along the Tinto River ranged from 105 to 107 cells/ml. The biodiversity detected was rather low, as would be expected for an extreme environment. Most of the cells stained with DAPI were members of the bacterial domain. Only 3% gave positive hybridization signals with archaeal probes. The most representative bacterial species in this system were Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (mean, 23%) and L. ferrooxidans (mean, 22%). The third most abundant bacterial group corresponded to members of the genus Acidiphilium. Other prokaryotes present at much lower numbers were the bacterium “Ferrimicrobium acidiphilum” and the closely related archaeon Ferroplasma acidiphilum. Taking into consideration the distribution of L. ferrooxidans and Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans along the river, we can conclude that these two organisms are mainly responsible for iron oxidation in the Tinto ecosystem.

The 16S rRNA gene sequences of Acidithiobacillus spp. present in the databases and those identified in this study fall into four different groups: a, b, c, and d (Fig. 3). Each group was detected in different proportions in different locations. Group a was dominant in the Origin 1 section of the river, while groups a, b, and c were detected at the Origin 2 site. In the middle course of the river, all groups were present, although numbers of representatives of group d remained low in all sampling stations. The variable population of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans found along the river strongly suggests that diverse groups have adapted to different conditions existing along the river (pH, iron concentration, redox potential, heavy metals, oxygen concentration, etc.).

Leptospirilli seemed to be more abundant than Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans in the headwaters (Origins 1 and 2). This could be due to the more extreme pH found at these locations. The capacity of L. ferrooxidans to grow at a lower pH than Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans has been shown in different studies (50). Interestingly, at Origin 1, the so-called group c1 seemed to be predominant, while at Origin 2, group c2 dominated. These variable populations of L. ferrooxidans that are able to distinguish between sampling sites in close proximity are an interesting example of specific adaptation, which should be further investigated at the physiological level.

Most of the leptospirilli from the Tinto River that were identified by using DGGE, FISH, and 16S rRNA gene sequences from native isolates (data not shown) belong to group c. Groups a and b were found in very low numbers (Table 5), a result that differs from those reported by Bond et al. (6). Although the phylogenetic clustering was similar (three clearly distinct groups), these authors found by comparing the sequences retrieved from Iron Mountain mine, California, that they clustered with group III (equivalent to group a in this work) and group II (equivalent to group b in this work). Independently, Coram and Rawlings (12), after analyzing 16S rRNA sequences of different Leptospirillum isolates from mines and industrial bioleaching processes, reported that they clustered with group I (equivalent to group c in this work) and group II (equivalent to group b in this work). They proposed the status of a new Leptospirillum species, L. ferriphilum, for the last group, reserving the nomenclature of L. ferrooxidans for the members of group I (group c in this work). No culturable isolates have been reported until now for group III (group a in this work). It is obvious from these results that further characterization of different Leptospirillum isolates is badly needed, especially when their key role in the oxidation of sulfidic minerals is taken into account.

The third genus dominating the microbial community of the Tinto River was Acidiphilium. This member of the α-Proteobacteria seems to be associated with Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans and L. ferrooxidans. This result is similar to those of the geomicrobiological studies on AMD, in which Acidiphilium spp. were found along with iron- and sulfur-oxidizing chemolithoautotrophs (27). It is believed that Acidiphilium spp. remove organic toxic compounds for Leptospirillum and Acidithiobacillus (27, 28). Species such as A. cryptum, A. organovorum, and A multivorum were detected in the Tinto ecosystem by DGGE and by use of probe ACD638. These species were probably the dominant α-proteobacteria, but there were additional α-proteobacteria that were not detected with this probe and that may correspond to other species of Acidiphilium or to other members of α-Proteobacteria. Species such as A. cryptum, A. organovorum, and A. multivorum were present in areas with more extreme conditions, probably in association with L. ferrooxidans, while in the rest of the river other Acidiphilium spp. or α-proteobacteria would be associated mainly with Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (Table 5).

The rest of the prokaryotes identified by DGGE, “Ferrimicrobium acidiphilum” and Ferroplasma acidiphilum, all related to bioleaching, were found in rather low numbers, so we believe that their role in the ecology of the Tinto ecosystem is minimal.

It is noteworthy that the two different molecular ecology techniques, DGGE and FISH, gave similar and complementary results, which accounted for nearly 80% of the prokaryotic diversity of the Tinto River, a rather complex and variable system. Furthermore, the agreement of the molecular ecology results with those generated by the conventional microbiological technique of isolation from enrichment cultures (34) (an uncommon situation in microbial ecology studies) underlines the consistency of these results.

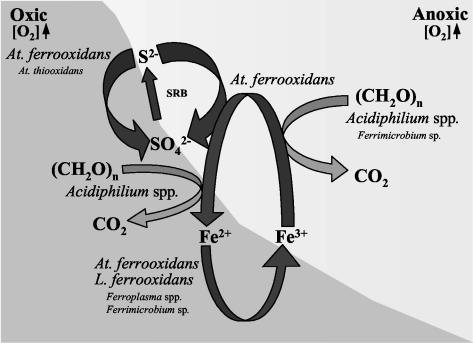

Microbial ecology model of the Tinto ecosystem.

The molecular biological identification and quantification of the main prokaryotic microorganisms thriving in the Tinto River, complemented by the physiological characterization of the corresponding isolates, allows the postulation of a model for the microbial ecology of the Tinto ecosystem based on the properties of pyrite, the main chemolithotrophic substrate available in the Iberian Pyrite Belt, and on the metabolic peculiarities of the major species present in the system.

The Tinto ecosystem seems to be under the control of iron. Reduced iron, from mineral ores and solution, is the energy source for both L. ferrooxidans and Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, resulting in the production of ferric iron. Oxidized iron is responsible for the maintenance of a constant acidic pH along the river (24). On the other hand, Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans can grow under anaerobic conditions by using reduced sulfur compounds, such as the elemental sulfur generated by the polysulfide oxidation mechanism of metal sulfides (53), as electron donors and ferric iron as an electron acceptor. Acidiphilium spp. have the capacity to respire reduced carbon compounds by using ferric iron as an electron acceptor in the absence or even in the presence of 60% oxygen (30). Therefore, these members of the α-Proteobacteria may, together with Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, be important for the reduction of ferric iron under the anaerobic or microaerobic conditions found at several locations along the river (RT7, RT9, and RT10). The iron cycle would be completed with these three species, and the constant acidic pH would also be explained. Interestingly enough, preliminary results have shown that several L. ferrooxidans isolates from the Tinto ecosystem are able to anaerobically oxidize (respire) iron by using reduced metals as electron acceptors, which suggests that a complete anaerobic iron cycle is also operative in the Tinto ecosystem (García-Moyano et al., personal communication).

Concerning the sulfur cycle, only Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, which is able to oxidize sulfur aerobically and anaerobically, has been detected in substantial numbers in the Tinto River by both conventional and molecular ecology techniques. Although isolation of Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans from the Tinto River has been reported previously (34), none of the molecular techniques used in this work were able to detect it. Given the close phylogenetic relationship between Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans and Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (Fig. 3), further investigation is needed before a final conclusion concerning the presence of the former species in the river can be reached. However, considering the specificity of the different probes used for FISH identification and the results shown in Table 5, it can be concluded that if Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans exists in the Tinto River, it must be present in rather low numbers. Sulfur reduction has been detected by FISH in several sampling sites of the Tinto ecosystem, although isolation and physiological characterization will be required to confirm the existence of this interesting microbial activity in the acidic waters of the Tinto River. Several reports have described sulfate-reducing activity in other acidic environments (29); thus, it is reasonable to assume that this activity is also occurring in the Tinto ecosystem, although at a rather low level, probably as a consequence of the high concentration of ferric iron present in the system (35).

Other microorganisms detected in the Tinto River may be also involved in this system, although their presence in low numbers precludes a critical role for them in the ecosystem. This would be the case for “Ferrimicrobium acidiphilum” and Acidimicrobium ferrooxidans, which can oxidize iron under aerobic conditions or reduce it under anaerobic conditions (8), and for Ferroplasma acidiphilum, whose metabolism is very similar to that of L. ferrooxidans and which could participate in the oxidation of iron. A basic geomicrobiological scheme for the Tinto River that takes into account the physiological properties of the microorganisms identified and their populations is given in Fig. 6.

FIG. 6.

Geomicrobiological model of the Tinto River showing the roles of the different microorganisms identified in the ecosystem. Microorganisms are shown associated with their roles in the iron and sulfur cycles. The type size of the organism designation is proportional to the respective cell density.

In conclusion, the use of complementary microbial ecology techniques allowed the prokaryotic diversity and the relative percentages of the different microorganisms along the Tinto River to be observed. In spite of the high level of eukaryotic diversity found in this peculiar habitat (3, 34), only three prokaryotic species, L. ferrooxidans, Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, and Acidiphilium spp., seem to play an important role in the generation and maintenance of the extreme conditions of the ecosystem. All of these species are conspicuous members of the iron cycle. Also, a coupled sulfur cycle seems to be operative in the Tinto ecosystem. Taking into account the characteristics of the habitat and what is known about the geomicrobiology of iron, which is fully operative in the system, we postulate that the Tinto River is under the control of iron, a model of interest in environmental microbiology.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. L. Ehrlich and the three anonymous referees for critical comments.

This work was supported by grants BIO99-0184 and BX2000-1385 from the Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, grant 07 M/0023/199 from the Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid, an institutional grant from the Fundación Areces to the CBM, and the Max Planck Society.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann, R. I., B. J. Binder, R. J. Olson, S. W. Chisholm, R. Devereux, and D. A. Stahl. 1990. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1919-1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann, R. I., W. Ludwig, and K. H. Schleifer. 1995. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol. Rev. 59:143-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amaral-Zettler, L. A., F. Gómez, E. Zettler, B. G. Keenan, R. Amils, and M. L. Sogin. 2002. Eukaryotic diversity in Spain's River of Fire. Nature 417:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bacelar-Nicolau, P., and D. B. Johnson. 1999. Leaching of pyrite by acidophilic heterotrophic iron-oxidizing bacteria in pure and mixed culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:585-590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bond, P. L., G. K. Druschel, and J. F. Banfield. 2000. Comparison of acid mine drainage microbial communities in physically and geochemically distinct ecosystems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4962-4978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bond, P. L., S. P. Smriga, and J. F. Banfield. 2000. Phylogeny of microorganisms populating a thick, subaerial, predominantly lithotrophic biofilm at an extreme acid mine drainage site. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3842-3849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boulter, A. 1996. Did both extensional tectonics and magmas act as major driver of convection cells during the formation of the Iberian Pyrite Belt massive sulfide deposits? J. Geol. Soc. London 153:181-184. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bridge, T. A. N., and D. B. Johnson. 1998. Reduction of soluble iron and reductive dissolution of ferric iron-containing minerals by moderately thermophilic iron-oxidizing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2181-2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brofft, J. E., J. V. McArthur, and L. J. Shimkets. 2002. Recovery of novel bacterial diversity from a forested wetland impacted by reject coal. Environ. Microbiol. 4:764-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brosius, J., T. J. Dull, D. D. Sleeter, and H. F. Noller. 1981. Gene organization and primary structure of a ribosomal RNA operon from Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 148:107-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colmer, A. R., K. L. Temple, and H. E. Hinkle. 1950. An iron-oxidizing bacterium from the acid drainage of some bituminous coal mines. J. Bacteriol. 59:317-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coram, N. J., and D. E. Rawlings. 2002. Molecular relationships between two groups of the genus Leptospirillum and the finding that Leptospirillum ferriphilum sp. nov. dominates South African commercial biooxidation tanks that operate at 40°C. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:838-845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daims, H., A. Bruhl, R. Amann, K. H. Schleifer, and M. Wagner. 1999. The domain-specific probe EUB338 is insufficient for the detection of all Bacteria: development and evaluation of a more comprehensive probe set. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 22:434-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daims, H., P. Nielsen, J. L. Nielsen, S. Juretschko, and M. Wagner. 2001. Novel Nitrospira-like bacteria as dominant nitrite-oxidizers in biofilms from wastewater treatment plants: diversity and in situ physiology. Water Sci. Technol. 43:416-523. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis, R. A., A. T. Welty, J. Borrego, J. A. Morales, J. G. Pendon, and J. G. Ryan. 2000. Rio Tinto estuary (Spain): 5000 years of pollution. Environ. Geol. 39:1107-1116. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards, K. J., P. L. Bond, T. M. Gihring, and J. F. Banfield. 2000. An archaeal iron-oxidizing extreme acidophile important in acidic mine drainage. Science 287:1796-1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards, K. J., T. M. Gihring, and J. F. Banfield. 1999. Seasonal variations in microbial populations and environmental conditions in an extreme acid mine drainage environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3627-3632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehrich, S., D. Behrens, E. Lebedeva, W. Ludwig, and E. Bock. 1995. A new obligately chemolithoautotrophic, nitrite-oxidizing bacterium, Nitrospira moscoviensis sp. nov., and its phylogenetic relationship. Arch. Microbiol. 164:16-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elbaz-Poulitchet, F., and C. Dupuy. 1999. Behaviour of rare earth elements at the fresh water-seawater interface of two acid mine rivers: the Tinto and the Odiel (Andalucía, Spain). Appl. Geochem. 14:1063-1072. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernández-Remolar, D. C., N. Rodríguez, F. Gómez, and R. Amils. The geological record of an acidic environment driven by iron hydrochemistry: the Tinto River system. J. Geophys. Res., in press.

- 21.Goebel, B. M., and E. Stackebrandt. 1994. Cultural and phylogenetic analysis of mixed microbial populations found in natural and commercial bioleaching environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1614-1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golovacheva, R. S., O. V. Golyshina, G. I. Karavaiko, A. G. Dorofeev, T. A. Pivovarova, and N. A. Chernykh. 1992. A new iron-oxidizing bacterium, Leptospirillum thermoferrooxidans sp. nov. Mikrobiologiya 61:744-750. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Golyshina, O. V., T. A. Pivovarova, G. I. Karavaiko, T. F. Kondrateva, E. R. Moore, W. R. Abraham, H. Lunsdorf, K. N. Timmis, M. M. Yakimov, and P. N. Golyshin. 2000. Ferroplasma acidiphilum gen. nov., sp. nov., an acidophilic, autotrophic, ferrous-iron-oxidizing, cell-wall-lacking, mesophilic member of the Ferroplasmaceae fam. nov. comprising a distinct lineage of the Archaea. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 50:997-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.González-Toril, E., F. Gómez, N. Rodríguez, D. Fernández, J. Zuluaga, I. Marín, and R. Amils. 2001. Geomicrobiology of the Tinto river, a model of interest for biohydrometallurgy. Part B, 639-650. In V. S. T. Cuminielly and O. García (ed.), Biohydrometallurgy: fundamentals, technology and sustainable development. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 25.González-Toril, E. 2002. Ecología molecular de la comunidad microbiana de un ambiente extremo: el río Tinto. Tesis doctoral. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain.

- 26.Hallberg, K. B., and D. B. Johnson. 2001. Biodiversity of acidophilic prokaryotes. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 49:37-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrison, J. A. P. 1985. The acidophilic thiobacilli and other acidophilic bacteria that share their habitat. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 38:265-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson, D. B. 1995. Selective solid media for isolating and enumerating acidophilic bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 23:205-218. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson, D. B. 1999. Importance of microbial ecology in the development of new mineral technologies. Part A, p. 645-656. In R. Amils and A. Ballester (ed.), Biohydrometallurgy and the environment: toward the mining of the 21st century. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 30.Johnson, D. B., and T. A. M. Bridge. 2002. Reduction of ferric iron by acidophilic heterotrophic bacteria: evidence for constitutive and inducible enzyme systems in Acidiphilium spp. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92:315-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keith, L. H. (ed.). 1996. Compilation of EPA's sampling and analysis methods, 2nd ed., p. 1036. CRC, Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 32.Kenzaka, T., N. Yamaguchi, K. Tani, and M. Nasu. 1998. rRNA-targeted fluorescent in situ hybridization analysis of bacterial community structure in river water. Microbiology 144:2085-2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leblanc, M., J. A. Morales, J. Borrego, and F. Elbaz-Poulichet. 2000. 4,500-year-old mining pollution in southwestern Spain: long-term implications for modern mining pollution. Econ. Geol. 95:655-662. [Google Scholar]

- 34.López-Archilla, A. I., I. Marín, and R. Amils. 2001. Microbial community composition and ecology of an acidic aquatic environment: the Tinto River, Spain. Microb. Ecol. 41:20-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lovley, D. R. 2000. Fe(III) and Mn(IV) reduction, p. 3-30. In D. R. Lovley (ed.), Environmental microbe-metal interactions. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 36.Ludwig, W., O. Strunk, S. Klugbauer, N. Klugbauer, M. Weizenegger, J. Neumaier, M. Bachleitner, and K. H. Schleifer. 1998. Bacterial phylogeny based on comparative sequence analysis. Electrophoresis 19:554-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mackintosh, M. E. 1978. Nitrogen fixation by Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 105:215-218. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maidak, B. L., J. R. Cole, T. G. Lilburn, C. T. Parker, P. R. Saxman, J. M. Stredwick, G. M. Garrity, B. Li, G. J. Olsen, S. Pramanik, T. M. Schmidt, and J. M. Tiedje. 2000. The RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) continues. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:173-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manz, W., R. Amann, W. Ludwig, M. Wagner, and K.-H. Schleifer. 1992. Phylogenetic oligodeoxynucleotide probes for the major subclasses of Proteobacteria: problems and solutions. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 15:593-600. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manz, W., M. Eisenbrecher, T. R. Neu, and U. Szewzyk. 1998. Abundance and spatial organization of Gram-negative sulfate-reducing bacteria in activated sludge investigated by in situ probing with specific 16S rRNA targeted oligonucleotides. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 25:43-61. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Margesin, R., and F. Schinner. 2001. Potential of halotolerant and halophilic microorganisms for biotechnology. Extremophiles 5:73-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muyzer, G., S. Hottenträger, A. Teske, and C. Wawer. 1996. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of PCR-amplified 16S rDNA—a new molecular approach to analyse the genetic diversity of mixed microbial communities, p. 3.4.4.1-3.4.4.22. In A. D. L. Akkermans, J. D. van Elsas, and F. J. de Bruijn (ed.), Molecular microbial ecology manual, 2nd ed. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 43.Neef, A. 1997. Anwendung der in situ-Einzelzell-Identifizierung von Bakterien zur Populations analyse in komplexen mikrobiellen Biozönosen. Ph.D. thesis. Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany.

- 44.Niehaus, F., C. Bertoldo, M. Kähler, and G. Antranikian. 1999. Extremophiles as a source of novel enzymes for industrial application. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 51:711-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Norris, P. R. 1990. Acidophilic bacteria and their activity in mineral sulfide oxidation, p. 3-27. In H. L. Ehrlich and C. Brierley (ed.), Microbial mineral recovery. McGraw-Hill, New York, N.Y.

- 46.Nübel, U., F. Garcia-Pichel, and G. Muyzer. 1997. PCR primers to amplify 16S rRNA genes from cyanobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3327-3332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raskin, L., J. M. Stromley, B. E. Rittmann, and D. A. Stahl. 1994. Group-specific 16S rRNA hybridization probes to describe natural communities of methanogens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1232-1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rawlings, D. E. 1997. Restriction enzyme analysis of 16S rRNA genes for a rapid identification of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans, Thiobacillus thiooxidans and Leptospirillum ferrooxidans strains in leaching environments, p. 9-18. In T. Vargas, C. A. Jerez, J. V. Wiertz, and H. Toledo (ed.), Biohydrometallurgical processing, vol. II. University of Chile, Santiago.

- 49.Rawlings, D. E. 2002. Heavy metal mining using microbes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56:65-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rawlings, D. E., H. Tributsch, and G. S. Hansford. 1999. Reasons why “Leptospirillum”-like species rather than Thiobacillus ferrooxidans are the dominant iron-oxidizing bacteria in many commercial processes for the biooxidation of pyrite and related ores. Microbiology 145:5-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Russell, N. J. 2000. Toward a molecular understanding of cold activity of enzymes from psychrophiles. Extremophiles 4:83-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sand, W., K. Rhode, B. Sobotke, and C. Zenneck. 1992. Evaluation of Leptospirillum ferrooxidans for leaching. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:85-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schippers, A., and W. Sand. 1999. Bacterial leaching of metal sulfides proceeds by indirect mechanisms via thiosulfate or polysulfides and sulfur. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:319-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schrenk, M. O., K. J. Edwards, R. M. Goodman, R. J. Hamers, and J. F. Banfield. 1998. Distribution of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans and Leptospirillum ferrooxidans: implications for generation of acidic mine drainage. Science 279:1519-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stahl, D. A., and R. Amann. 1991. Development and application of nucleic acid probes, p. 205-248. In E. Stackebrandt and M. Goodfellow (ed.), Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 56.van Geen, A., J. F. Adkins, E. A. Boyle, C. H. Nelson, and A. Palenques. 1997. A 120-year record of widespread contamination from mining of the Iberian Pyrite Belt. Geology 25:291-294. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wulf-Durand, P., L. J. Bryant, and L. I. Sly. 1997. PCR-mediated detection of acidophilic, bioleaching-associated bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2944-2948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]