Abstract

Genome-wide expression analysis of an industrial strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae during the initial stages of an industrial lager fermentation identified a strong response from genes involved in the biosynthesis of ergosterol and oxidative stress protection. The induction of the ERG genes was confirmed by Northern analysis and was found to be complemented by a rapid accumulation of ergosterol over the initial 6-h fermentation period. From a test of the metabolic activity of deletion mutants in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway, it was found that ergosterol is an important factor in restoring the fermentative capacity of the cell after storage. Additionally, similar ERG10 and TRR1 gene expression patterns over the initial 24-h fermentation period highlighted a possible interaction between ergosterol biosynthesis and the oxidative stress response. Further analysis showed that erg mutants producing altered sterols were highly sensitive to oxidative stress-generating compounds. Here we show that genome-wide expression analysis can be used in the commercial environment and was successful in identifying environmental conditions that are important in industrial yeast fermentation.

Yeast are subjected to many types of stress and metabolic challenges throughout industrial fermentation processes. These range from the physical (pressure and shearing) to the chemical, such as osmotic shock, oxidative stress, and secondary metabolite toxicity (3). Yeast fermentation is an ancient process, and years of exposure to these conditions have resulted in industrial yeast strains that have evolved mechanisms to adapt to them. However, with the advent of new processes that increase yields or are more cost-effective, different and increased demands have been placed on the yeast. This can lead to conditions that overwhelm yeast defenses, causing defective fermentations with poor sugar utilization, reduced ethanol production, and the synthesis of poor flavor qualities (21, 38, 55). Increased stress has also been found to have an impact on the activity and longevity properties of the yeast and therefore affect their performance in subsequent fermentations (30, 47, 53).

To better understand the determinants of defective brews, research is often carried out by changing single parameters in model systems that can be reliably reproduced. This process has been very successful in determining the molecular mechanisms involved in protection against individual stresses. However, industrial fermentations are dynamic in nature, with multiple stresses or biological changes interacting simultaneously to cause the physiological traits of the yeast or fermentation parameters. Thus, studying the effect of individual stresses on yeast does not give the full picture of the important environmental parameters in fermentation.

Yeast can rapidly adjust its genomic expression program to ultimately produce proteins that can detect and respond to biological challenges (29). In the majority of cases, gene expression levels reflect protein production and activity that have been elicited to cope with changing environmental conditions. Gene expression changes of heat shock protein and osmotic stress-response genes have been used to monitor microvinification processes for stress conditions (2, 46). The sequencing of the yeast genome and analytical techniques enabling the quantification of expression levels of a large number of individual genes have facilitated a major step forward in the ability to identify genes that have altered gene expression patterns in response to changing environmental conditions (8, 23). This genome-wide expression technology was applied to the study of the response of an industrial yeast strain during an industrial fermentation process. Genes were identified as induced in the initial stages of a lager fermentation that gave insights into the conditions that were affecting the yeast and therefore important to the fermentation process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

The polyploid industrial yeast strain used was Lager 1, provided by Carlton & United Breweries, Abbotsford, Victoria, Australia (17). The ergosterol mutant strains (constructed by an international consortium of yeast laboratories) (65) were in the BY4743 (MATa/MATα his3Δ1/his3Δ1 leu2Δ0/leu2Δ0 met15Δ0/MET15 LYS2/lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0/ura3Δ0) background. The mutant strains are referred to in the text by the deleted gene name (Δerg3, Δerg4, Δerg5, or Δerg6 mutant). The industrial pilot-plant fermentation was carried out with a fermentation vessel with a capacity for 20 liters of brewer's wort. The wort (12% sugar content) and acid-washed Lager 1 strain were produced in a brewery plant (Carlton & United Breweries). Multiple aliquots of cells and supernatant were harvested at 0, 1, 6, 15, and 23 h; frozen with liquid nitrogen; and stored at −80°C. Total RNA was isolated from aliquots the next day for genome-wide expression and Northern analysis. The kinetic gene expression analysis was carried out on Lager 1 yeast strain cells harvested from a full-scale 500,000-liter industrial lager fermentation at Carlton and United Breweries, Ltd., Kent Brewery, Sydney, Australia. Cells were isolated at the start of the filling stage (0 min), 1 h, and every 3 h until 24 h.

BY4743 and deletion mutants were grown on YPD-based medium (0.5% yeast extract, 1% peptone, 2% glucose) for 3 days and then harvested and stored at 4°C for 2 days. The extended incubation period was carried out to mimic the industrial fermentation conditions and to deplete cells of ergosterol (54). The cultured cells were washed for 2 h at 4°C in sterile deionized distilled water acidified to pH 2.2 with 3 M phosphoric acid (14). These cells were pitched into 1 liter of wort (12% sugar concentration) in 2-liter Schott bottles at a concentration of 0.3 g (wet weight) per 100 ml. Gas production was monitored by placing 2-ml aliquots into the Multi Fermentation Screening System as previously described (6, 20). The gas production was defined as pressure sensor voltage values. The results shown are average values from triplicate assays of duplicate experiments with standard errors of <15%.

Total RNA preparation and synthesis of cDNA.

Total RNA for Northern hybridization and cDNA synthesis was isolated from yeast cells by using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Life Technologies). [33P]dCTP-labeled cDNA was synthesized by combining 3 μg of total RNA and 2 μg of oligo(dT) (10- to 20-mer mixture; Research Genetics) in a final volume of 10 μl, heated for 10 min at 70°C, and chilled on ice. The elongation reaction mixture consisted of first-strand buffer (Life Technologies); dithiothreitol (3.3 mM); dATP, dGTP, and dTTP (1 mM each); Superscript II reverse transcriptase (300 U; Life Technologies); and [33P]dCTP (100 μCi, 3,000 Ci/mmol; ICN Radiochemicals). The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 90 min before purification through a Bio-Spin 6 chromatography column (Bio-Rad).

GeneFilters hybridization.

GeneFilters (Research Genetics) were prehybridized for 4 h in 5 ml of MicroHyb hybridization solution [5 μg of poly(dA); Research Genetics] at 42°C in a Hybaid roller oven. The purified cDNA probe was denatured for 5 min in a boiling water bath, added to prehybridization mixture, and hybridized at 42°C for 16 h. The filters were washed according to the manufacturer's recommendations, and to ensure they remained moist to facilitate stripping between hybridizations, they were placed on 3M filter paper, soaked with sterile distilled water, and wrapped in plastic cling wrap. A digital image was obtained after 48 h of exposure on a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Before the next hybridization, the filters were submerged in 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate previously heated to 100°C and left at room temperature for 1 h with gentle agitation. Stripping efficiency was determined to reduce original signals by more than 95%.

Data analysis.

Preliminary quantification of spot intensities was carried out by using the grid system and volume integration in the ImageQuaNT v4.2a software package, since conversion of digital images to TIFF and analysis using the Pathways software has been reported to greatly underestimate actual differences (48). Gene expression changes were confirmed with a repeat set of filters, and in cases in which expression values were unreliably small or changes were only evident in one set of filters, the changes were discarded. To determine the degree of induction of gene expression, spot intensities were normalized against ACT1 for each filter, and the relative mRNA level at 1 h into fermentation was divided by values after 23 h. The averages of the fold changes are listed in Table 1 for the genes whose mRNA level at 1 h was induced at least threefold in both sets of filters. The original image files were inspected individually for false positives arising due to nonspecific radiation binding or the spreading of radioactive probe into neighboring gene spots from highly expressed genes.

TABLE 1.

Genes induced in the first hour of an industrial fermentation compared to those induced by the 23rd h

| Open reading frame | Gene name | Fold induction | Gene description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid, fatty acid, and sterol metabolism | |||

| YGL055w | OLE1 | 48 | Stearoyl-CoA desaturase, synthesis of unsaturated fatty acids |

| YPL028w | ERG10 | 26 | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase (acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase) |

| YPR065w | ROX1 | 20 | Represses transcription of ERG11, OLE1, HEM13, and COX5b |

| YHR179w | OYE2 | 19 | NADPH dehydrogenase (old yellow enzyme), isoform 2 |

| YHR007c | ERG11 | 17 | Cytochrome P450 (lanosterol 14α-demethylase) |

| YPL117c | IDI1 | 13 | Isopentenyl-diphosphate δ-isomerase (IPP isomerase) |

| YDR497c | ITR1 | 10 | Myoinositol permease (major) |

| YGL001c | ERG26 | 10 | C-3 sterol dehydrogenase, C-4 decarboxylase |

| YMR015c | ERG5 | 9.6 | Cytochrome P450, δ-22(23) sterol desaturase |

| YDR232w | HEM1 | 7.5 | 5-Aminolevulinate synthase, first step in heme biosynthesis pathway |

| YML126c | ERG13 | 6.7 | 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA synthase |

| YPL057c | SUR1 | 5.7 | Involved in maintenance of phospholipid levels |

| YGR175c | ERG1 | 5.5 | Squalene monooxygenase (squalene epoxidase) |

| YGR060w | ERG25 | 5.1 | C-4 sterol methyl oxidase |

| YGL013c | PDR1 | 4.0 | Regulates genes involved in multiple drug resistance |

| YNL231c | PDR16 | 3.2 | Phosphatidylinositol transfer protein involved in lipid biosynthesis |

| YLR056w | ERG3 | 3.1 | C-5 sterol desaturase, an iron, non-heme, oxygen-requiring enzyme |

| Cell stress | |||

| YDR353w | TRR1 | 53 | Thioredoxin reductase |

| YDR077w | SED1 | 41 | Cell surface glycoprotein, contributes to stress resistance |

| YKR071c | DRE2 | 23 | Promoter has at least one putative Yap1p-binding site |

| YGL163c | RAD54 | 11 | ATPase, required for mitotic recombination and DNA repair |

| YGR086c | 10 | Gene expression is induced by high salt and low pH | |

| YML130c | ERO1 | 9.8 | Required for protein disulfide bond formation in the endoplasmic reticulum |

| YGR088w | CTT1 | 9.6 | Catalase T (cytosolic), detoxification of superoxide radicals and H2O2 |

| YCR102c | 9.4 | Gene expression is induced by hydrogen peroxide | |

| YBR114w | RAD16 | 9.1 | Component of the nucleotide excision repair factor 4 |

| YLR109w | AHP1 | 8.9 | Antioxidant function is dependent upon the thioredoxin system |

| YNL190w | 8.9 | Gene expression is induced under hyperosmotic conditions | |

| YNL134c | 8.6 | Gene expression is induced by hydrogen peroxide | |

| YBR244w | GPX2 | 7.1 | GSH peroxidase, protection against hydroperoxides |

| YDR453c | TSA2 | 6.6 | Cytoplasmic thiol peroxidase |

| YJL101c | GSH1 | 6.0 | GSH biosynthesis |

| YJR127c | ZMS1 | 5.8 | May be required for adaptation of cells to changes to acidic pH |

| YKR042w | UTH1 | 5.5 | Gene expression is induced by hydrogen peroxide |

| YDR513w | TTR1 | 4.7 | Glutaredoxin (thioltransferase, GSH reductase) |

| YKR075c | 4.7 | Two putative STRE's are present in the promoter | |

| YML053c | 4.0 | Induced expression under cell damaging conditions | |

| YGR209c | TRX2 | 3.4 | Thioredoxin II |

| YJR140c | HIR3 | 3.2 | Transcription regulator that controls expression of histone genes |

| Amino acid involvement | |||

| YDR502c | SAM2 | 29 | S-Adenosylmethionine synthetase 2 |

| YAL012w | CYS3 | 14 | Cystathionine γ-lyase, generates cysteine from cystathionine |

| YMR038c | LYS7 | 13 | Involved in lysine biosynthesis, oxidative stress protection |

| YOR302w | 12 | Arginine attenuator peptide | |

| YGR055w | MUP1 | 11 | High-affinity cysteine and methionine permease |

| YDL131w | LYS21 | 9.2 | Homocitrate synthase isoenzyme, involved in lysine metabolism |

| YDR481c | PHO8 | 8.5 | Vacuolar alkaline phosphatase (ALP) |

| YBR106w | PHO88 | 7.2 | Membrane protein involved in inorganic phosphate transport |

| YDR037w | KRS1 | 6.7 | Lysyl-tRNA synthetase, cytoplasmic |

| YDL182w | LYS20 | 5.5 | Homocitrate synthase isoenzyme, involved in lysine biosynthesis |

| YDL106c | PHO2 | 5.3 | Homeodomain protein required for expression of phosphate pathway |

| YGR155w | CYS4 | 5.1 | Cystathionine β-synthase |

| YDR173c | ARG82 | 4.4 | Inositol polyphosphate multikinase |

| YBR112c | SSN6 | 3.4 | General repressor of Pol II transcription |

| Cell wall | |||

| YER150w | SPI1 | 15 | Protein induced in stationary phase, has similarity to Sed1p |

| YNL161w | CBK1 | 5.7 | Serine/threonine kinase |

| YBL101c | ECM21 | 8.3 | Protein possibly involved in cell wall structure or biosynthesis |

| YOR009w | TIR4 | 6.8 | Member of the seripauperin (PAU) cell wall mannoproteins |

| YIL130w | GIN1 | 4.2 | Putative transcription factor, may have a role in cell wall integrity |

| YGR023w | MTL1 | 3.6 | Protein that acts with Mid2p in signal transduction of cell wall stress |

| Cell cycle | |||

| YCR093w | CDC39 | 6.4 | Member of the CCR4-Not complex |

| YGR049w | SCM4 | 4.5 | Suppresses temperature-sensitive allele of CDC4 |

| YOR113w | AZF1 | 4.4 | Involved in glucose-dependent induction of CLN3 transcription |

| YMR273c | ZDS1 | 3.8 | Regulation of SWE1 and CLN2 transcription, Sir3p phosphorylation/PICK> |

| Open reading frame | Gene name | Fold induction | Gene description |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | |||

| YPL061w | ALD6 | 95 | Cytosolic acetaldehyde dehydrogenase |

| YMR011w | HXT2 | 50 | High-affinity hexose transporter |

| YML048w | GSF2 | 12 | Involved in glucose repression and possibly cell wall biosynthesis |

| YER062c | HOR2 | 11 | dl-Glycerol phosphate phosphatase (sn-glycerol-3-phosphatase) |

| YIL053w | RHR2 | 10 | dl-Glycerol phosphate phosphatase (sn-glycerol-3-phosphatase) |

| YML054c | CYB2 | 6.0 | Cytochrome b2, catalyzes the conversion of l-lactate to pyruvate |

| YNR052c | POP2 | 5.3 | Component of the CCR4 complex required for glucose derepression |

| Energy generation | |||

| YER141w | COX15 | 29 | Involved in heme A biosynthesis and cytochrome oxidase assembly |

| YAL039c | CYC3 | 7.1 | Cytochrome c heme lyase, linkage of heme to apocytochrome c |

| YKL032c | IXR1 | 5.7 | Transcription factor that confers O2 regulation on COX5B |

| YKR046c | 3.5 | Hyperexpressed upon heat shock, and glucose deficiency | |

| YBL080c | PET112 | 3.4 | Protein that may have a general role in mitochondrial translation |

| RNA processing/modification | |||

| YPL212c | PUS1 | 27 | Pseudouridine synthase |

| YDR432w | NPL3 | 7.7 | Protein involved in 18S and 25S rRNA processing |

| YLL013c | PUF3 | 6.7 | Protein involved in metabolism of COX17 mRNA |

| YDR228c | PCF11 | 6.6 | Component of pre-mRNA cleavage and polyadenylation factor I |

| YGL122c | NAB2 | 6.5 | Nuclear poly(A)-binding protein |

| YHL024w | RIM4 | 3.5 | Protein required for sporulation and formation of meiotic spindle |

| YPL190C | NAB3 | 3.1 | May be required for packaging pre-mRNAs into ribonucleoprotein |

| Protein modification and synthesis | |||

| YLR249w | YEF3 | 44 | Translation elongation factor EF-3A |

| YBR105c | VID24 | 28 | Protein required for vacuolar import and degradation of Fbp1p |

| YKL054c | VID31 | 11 | Protein involved in vacuolar import and degradation |

| YPL106c | SSE1 | 10 | Heat shock protein of the HSP70 family |

| YDL229w | SSB1 | 5.3 | Heat shock protein of HSP70 family |

| YBR118w | TEF2 | 4.9 | Translation elongation factor EF-1α, identical to Tef1p |

| YDR385w | EFT2 | 4.8 | Translation elongation factor EF-2 |

| YAL005c | SSA1 | 4.5 | Heat shock protein of the HSP70 family |

| YEL036c | ANP1 | 3.9 | Protein of the cis-Golgi |

| YBR034c | HMT1 | 3.9 | Protein arginine methyltransferase |

| Signal transduction | |||

| YGR040w | KSS1 | 10 | Serine/threonine protein kinase |

| YDL035c | GPR1 | 10 | G protein-coupled receptor coupled to Gpa2p |

| YPL093w | NOG1 | 6.2 | Putative essential nucleolar GTP-binding protein |

| YDR099w | BMH2 | 3.4 | Homolog of mammalian 14-3-3 protein |

| YOR360c | PDE2 | 3.3 | Low-Km (high affinity) cyclic AMP (cAMP) phosphodiesterase |

| Pol II transcription | |||

| YDL005c | MED2 | 7.6 | Component of RNA polymerase II holoenzyme |

| YMR016c | SOK2 | 6.9 | Involved in regulation of cAMP-dependent kinase growth |

| YMR043w | MCM1 | 6.7 | MADS box family |

| YBR289w | SNF5 | 5.9 | Component of SWI-SNF global transcription activator complex |

| YPL089c | RLM1 | 5.0 | Transcription factor of the MADS box family |

| YNL027w | CRZ1 | 4.6 | Calcineurin-dependent transcription |

| YIR023w | DAL81 | 4.4 | Transcriptional activator for allantoin, 4-aminobutyric acid (GABA) |

| Other | |||

| YJL116c | NCA3 | 84 | May participate in regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis |

| YGR123c | PPT1 | 26 | Protein serine/threonine phosphatase of unknown function |

| YJL079c | PRY1 | 13 | May have a role in mating efficiency |

| YDL039c | PRM7 | 11 | Transcription is induced by α-factor |

| YDR505c | PSP1 | 9.9 | High-copy suppressor of temperature-sensitive mutations in Cdc17p |

| YLR206w | ENT2 | 6.7 | Epsin homolog required for endocytosis |

| YDL161w | ENT1 | 6.6 | Epsin homolog required for endocytosis |

| YBL033c | RIB1 | 5.8 | GTP cyclohydrolase II, riboflavin biosynthesis pathway |

| YBR130c | SHE3 | 4.9 | Protein involved in localization of ASH1 mRNA |

| YDR289c | RTT103 | 4.9 | Regulator of Ty1 transposition, has similarity to Spt8p |

| YJL073w | JEM1 | 4.4 | DnaJ-like protein of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane |

| YGL056c | SDS23 | 4.0 | Spindle pole body protein, has similarity to Schizosaccharomyces pombe sds23/moc1 |

| YGL215w | CLG1 | 3.5 | Cyclin-like protein, associates with Pho85p cyclin-dependent kinase |

| YKL187c | 12 | Protein with similarity to 4-mycarosyl isovaleryl-CoA transferase | |

| YLL055w | 7.8 | Member of the allantoate permease family | |

| YGR052w | 6.7 | Serine/threonine protein kinase of unknown function | |

| YIL105c | 3.7 | Protein with similarity to Ask10p and Yn1047p | |

| YDR233c | 3.7 | Protein that associates with the endoplasmic reticulum | |

| YBL081w | 3.6 | mRNA abundance increases during glucose upshift | |

| YBL094c | 9.6 | Unknown | |

| YGR161c | 9.5 | Unknown | |

| YBR016w | 9.1 | Unknown | |

| YDL038c | 9.0 | Unknown | |

| YMR002w | 8.7 | Unknown | |

| YOR062c | 8.1 | Unknown | |

| YMR010w | 7.9 | Unknown | |

| YBR113w | 7.5 | Unknown | |

| YDL228c | 7.4 | Unknown | |

| YLR064w | 7.3 | Unknown | |

| YKR060w | 6.9 | Unknown | |

| YPR022c | 6.3 | Unknown | |

| YJL048c | 6.1 | Unknown | |

| YEL070w | 5.9 | Unknown | |

| YGR079w | 5.8 | Unknown | |

| YDR492w | 4.8 | Unknown | |

| YMR124w | 4.5 | Unknown |

The web-based cluster interpreter FunSpec (49) was used for the statistical evaluation of the induced set of genes with respect to existing annotated databases containing information on the functional roles and biochemical properties of gene products. The data set in Table 1 was queried against the Munich Information Center for Protein Sequences (MIPS) (36) and Gene Ontology (GO) (23a) compiled knowledge databases (last downloaded June 2002) online at http://funspec.med.utoronto.ca. The Bonferroni correction was applied to compensate for multiple testing over many categories of the databases (49). A P value cutoff of 0.01 was used to determine clusters that were enriched using the “guilt-by-association” predictive methodologies.

Northern hybridization.

Aliquots (10 μg) of total RNA were separated by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel, transferred to Hybond-N nylon membrane (Amersham Life Science), and hybridized with 32P-labeled DNA-specific probes. DNA fragments were generated by PCR from yeast chromosomal DNA of genes ERG3 (ERG3F, 5′-TCGTTGGCAGCTAATATTCC; and ERG3B, 5′-GATGGATTGCAAAAACCCGT), TRR1 (TRR1F, 5′-TATTTGGCCAGGGCAGAAAT; and TRR1B, 5′-TTTACCATCCCCCTTAGCTT), ERG10 (ERG10F, 5′-TTGGTTCATTCCAGGGTTCT; and ERG10B, 5′-TTGGAAAACAGTCCTTGCAG), and ACT1 (ACT1F and ACT1B, both 5′-). Probes were labeled with the Megaprime DNA labeling system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Images of probe bands were obtained on a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) and analyzed with ImageQuaNT v4.2a software.

Ergosterol assays.

Ergosterol was extracted, fractionated, and quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as outlined by Böcking et al. (7). Total lipids from yeast cells (2.0 to 2.5 g wet weight) were extracted with chloroform-methanol as described by Parks et al. (44) and redissolved in chloroform. Dry weight was calculated by measuring weight before and after heating of cells (4.5 to 5.0 g wet weight) to 80°C overnight. The extracted total lipids were applied to a Sep-Pak Plus silica cartridge (Waters) and conditioned with hexane-ethyl acetate, and the fraction containing the ergosterol was eluted with acetone. Ergosterol was identified and quantified by comparison to an internal standard (ergosterol; Sigma) during reversed-phase HPLC with a Hewlett-Packard series 1100 HPLC system. Quantification of ergosterol by peak area was carried out at a UV absorption of 282 nm. Values are means ± standard deviations (SD) for three injections of duplicate samples for each time point.

RESULTS

Genome-wide expression analysis.

To determine whether data generated from genome-wide expression analysis during industrial processes could identify meaningful transcription profiles, acid-washed industrial yeast were pitched into commercially prepared wort, and total RNA samples were isolated from cells harvested at 1 h and 23 h into the fermentation. Research Genetics Yeast GeneFilters were hybridized with radiolabeled cDNA probes produced from the total RNA. Each hybridization was carried out in duplicate, and the [α-33P]dCTP signal intensities ranged from background (5 to 400 dpm) to levels of approximately 30,000 dpm.

The mRNA level of over 100 genes was at least threefold higher in the first hour of fermentation compared to that of the 23rd h when fermentation was under way. They were grouped into functional categories (Table 1) according to the biological roles assigned by the Yeast Protein Database (26). The genes were involved in many cellular processes, ranging from lipid, fatty acid, and sterol metabolism to amino acid metabolism, cell stress, RNA, and protein modification (Table 1). A statistical evaluation of this set of genes with respect to their functional roles was carried out by using the FunSpec web-based clustering tool (49). The up-regulated genes were submitted to the MIPS and GO yeast databases on the FunSpec web site. The categories that were statistically most unlikely to occur by chance were those involved with sterol biosynthesis and metabolism and redox homeostasis from the GO yeast databases and the category “cell rescue, defense, and virulence” from the MIPS databases (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Functional categories that are overrepresented in the induced genesa

| Category | P valueb | Induced genes in 1st h of fermentation |

|---|---|---|

| GO biological process | ||

| Sterol biosynthesis | 5.80 × 10−10 | ERG26 ERG25 ERG1 ERG11 ERG3 ERG13 ERG5 PDR16 ERG10 IDI1 |

| Sterol metabolism | 1.76 × 10−9 | ERG26 ERG25 ERG1 ERG11 ERG3 ERG13 ERG5 PDR16 ERG10 IDI1 |

| Ergosterol biosynthesis | 2.81 × 10−9 | ERG26 ERG25 ERG1 ERG11 ERG3 ERG13 ERG5 ERG10 IDI1 |

| Ergosterol metabolism | 2.82 × 10−9 | ERG26 ERG25 ERG1 ERG11 ERG3 ERG13 ERG5 ERG10 IDI1 |

| Steroid biosynthesis | 6.39 × 10−9 | ERG26 ERG25 ERG1 ERG11 ERG3 ERG13 ERG5 PDR16 ERG10 IDI1 |

| Steroid metabolism | 1.96 × 10−8 | ERG26 ERG25 ERG1 ERG11 ERG3 ERG13 ERG5 PDR16 ERG10 IDI1 |

| Redox homeostasis | 1.63 × 10−6 | TRR1 TSA2 TTR1 TRX2 AHP1 |

| Regulation of redox homeostasis | 1.63 × 10−6 | TRR1 TSA2 TTR1 TRX2 AHP1 |

| MIPS functional classification | ||

| Cell rescue, defense, and virulence | 5.19 × 10−7 | TSA2 TTR1 TRX2 AHP1 GSH1 GPX2 SED1 UTH1 SSA1 TIP1 HOR2 PDR1 CTT1 GRR1 LYS7 MCM1 ZDS1 CRZ1 TIR4 SSE1 ERG5 ERG11 |

Gene functions were identified by addressing the GO and MIPS databases with the FunSpec statistical evaluation program.

Probability of the functional set occurring as a chance event.

Ergosterol biosynthesis induction during the initial stages of fermentation.

Ergosterol is an essential lipid component of yeast membranes, and its biosynthesis involves over 20 reactions (16). IDI1 and eight ERG genes were included in the overrepresented sterol categories (Table 2). ERG10 and ERG13 catalyze the initial steps of sterol biosynthesis converting two acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) molecules to hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA (31, 52). Subsequently, isopentenyl pyrophosphate isomerase (IDI1, Table 1) produces the dimethylallyl pyrophosphate needed for the formation of farnesyl pyrophosphate, the ultimate fate of the mevalonate pathway (1). The conversion of farnesyl pyrophosphate to the end product, ergosterol, is unique to yeast, and six of the genes required for this pathway (ERG1, ERG11, ERG25, ERG26, ERG3, and ERG5) are represented in these results (Tables 1 and 2).

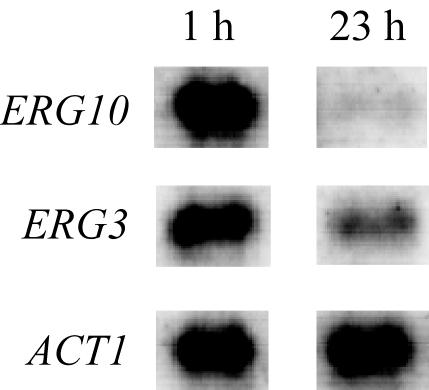

To validate the GeneFilters expression data, ERG gene expression was measured by Northern blotting with the total RNA that was analyzed in the genome-wide expression analysis. The ERG10 gene was used as an example of high induction (26-fold), and for lower induction, the ERG3 gene (threefold) expression was measured. The transcript levels of each gene were of similar intensities in the first hour and were induced compared to their expression in the 23rd h (Fig. 1). The differences in fold changes in induction appear to be the result of the very low expression of ERG10 in the 23rd h (Fig. 1). These expression patterns correlate with the genome-wide expression profile validating the results for these genes.

FIG. 1.

Northern blot verification of genome-wide expression analysis. The figure is representative of expression levels of ERG10 and ERG3 measured by using the duplicate total RNA samples isolated from the Lager 1 strain 1 h and 23 h into a pilot-plant fermentation.

To confirm that induced ERG gene expression in the initial hour of fermentation corresponded with an increase in ergosterol levels, the sterol content of cells harvested during the first 23 h of the pilot-plant fermentation was measured by sterol extraction and reversed-phase HPLC. Figure 2 shows that the cells initially pitched into the fermentation were depleted of ergosterol (time zero). Consistent with induced gene expression, the ergosterol levels increased significantly over the first hour of fermentation and began to plateau around the sixth hour (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

ERG gene induction in the Lager 1 strain leads to ergosterol accumulation during the initial stages of the pilot-plant fermentation. Quantification of ergosterol in yeast cells was carried out by reversed-phase HPLC.

Ergosterol is an essential requirement for optimal metabolic activity.

To examine the importance of ergosterol for yeast metabolic activity, we monitored the gas production of strains deleted for the genes ERG6, ERG3, ERG5, and ERG4, which encode the enzymes catalyzing four of the last five steps of ergosterol synthesis. It was evident that all deletion strains producing altered sterols were delayed in gas production compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 3). In the mutants, gas production was delayed to the greatest extent in the strain containing the Δerg6 mutation (the earliest in the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway). The delay was between 6 to 9 h, and the gas production rate was lower than that of the wild-type strain. Gas production was also delayed in the Δerg3 mutant, and although not as pronounced as in the Δerg6 mutant, its gas production was delayed between 3 and 6 h.

FIG. 3.

Effect of ERG mutations on the metabolic activity of BY4743 yeast cells. Cells were stored for 2 days, acid washed, and pitched into industrial-grade wort. Metabolic activity was monitored as the amount of gas produced. Shown are results for wild-type strain, BY4743 (⋄), and the Δerg6 (□), Δerg3 (▵), Δerg5 (○), and Δerg4 (X) mutants.

Deletion of the last two steps in the biosynthesis of ergosterol appeared to be less deleterious to gas production. The Δerg4 and Δerg5 mutants showed a delay in gas production of around 1 to 2 h; however, the rate of gas production was the same as that of the wild type (Fig. 3).

Oxidative stress response during the initial stages of fermentation.

The remaining categories found to be functionally enriched in the initial stages of the fermentation were (i) redox homeostasis and (ii) cell rescue, defense, and virulence. Both of these categories contain genes that are involved in mechanisms that protect the cell against oxidative stress (Table 2). The TRX2 gene encodes the cytosolic form of thioredoxin that is involved in reducing protein disulfides (37). Thioredoxin can also be used as the hydrogen donor for organic peroxide reduction by the thiol peroxidases encoded by the TSA2 and AHP1 genes (42). Subsequently, the TRR1 gene product, thioredoxin reductase, reduces the oxidized thioredoxin produced from these reactions (10).

The glutaredoxin gene (TTR1) encodes an oxidoreductase that has considerable functional overlap with thioredoxin. It has been shown to reactivate a number of oxidized proteins as a result of thiol oxidation (58). However, unlike thioredoxin, glutaredoxin is recycled to its reduced form by the oxidation of glutathione (GSH) to its oxidized form, GSSG (27). This correlates with gene expression results indicating an increase in GSH production. Cysteine is a vital component of GSH synthesis, and the genes involved in its high-affinity transport (MUP1) (32) and synthesis from homocysteine (CYS3 and CYS4) (40, 41) were up-regulated in the first hour (Table 1). The next step in GSH production involves the GSH1 gene (sixfold induction; Table 1), whose product catalyzes the first and rate-limiting step in the biosynthesis of GSH (39).

Kinetic response in gene expression during the initial fermentation period.

To analyze the gene expression kinetics of the ergosterol and oxidative stress responses, the transcript levels of ERG10 and TRR1 were measured over the initial 24 h of a full-scale factory lager fermentation (500,000 liters). Northern blot analyses showed that the ERG10 and TRR1 genes were induced in the first hour of the fermentation, as found in the genome-wide expression analysis (Fig. 4). The level of induction for both genes peaked around 1 h and gradually decreased until no induction was evident around 6 h (Fig. 4). These results highlight the similarity in the gene expression responses of ergosterol biosynthesis and oxidative stress response genes.

FIG. 4.

Northern blot analysis of ERG10 (▵) and TRR1 (▪) gene expression in the Lager 1 strain during the initial 24 h of a 500,000-liter industrial lager fermentation. The graphical representation of gene expression is relative to that of ACT1.

Altered sterol production renders yeast cells hypersensitive to oxidative stress.

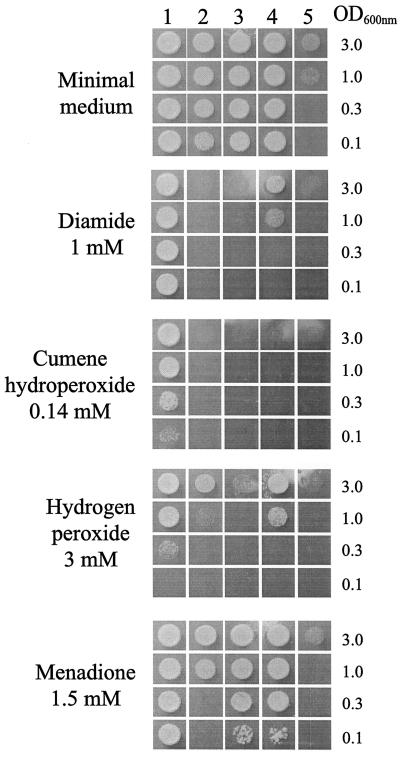

The contribution of ergosterol to protecting cells from oxidative stress was determined by measuring the sensitivity of ergosterol biosynthesis mutants (Δerg3, Δerg4, Δerg5, and Δerg6) to constant exposure to oxidative stress. When challenged with a range of oxidants, the ability of the cells producing altered sterols to grow was severely reduced (Fig. 5). The sensitivity of the mutants was relatively high to the organic hydroperoxide (cumene hydroperoxide) and the thiol oxidant diamide (Fig. 5). The strains were sensitive to hydrogen peroxide and superoxides but to a lesser extent than to the other oxidants (Fig. 5). The ability of the Δerg6 mutant to grow on YPD was lower than those of the wild type and other mutant strains (Fig. 5). This slow growth is consistent with the long delay in producing gas when inoculated into wort (Fig. 3). The ability of this strain to grow was impeded even further when oxidants were present (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Effect of ERG mutations on the ability of BY4743 yeast cells to respond to oxidative stress. Cells were grown to the stationary phase, diluted to the indicated optical density at 600 nm (OD600), and applied as spots to YPD plates containing the indicated oxidants. Plates were photographed after 2 days of growth at 30°C. Shown are results for the wild-type strain, BY4743 (column 1), and the Δerg3 (column 2), Δerg4 (column 3), Δerg5 (column 4), and Δerg6 (column 5) mutants.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this genome-wide expression analysis was to determine the feasibility of using GeneFilters in the identification and classification of genes that are responsive in industrial lager fermentations. This approach gave an overview of genes that were responsive in the first hour of fermentation compared to the 23rd h. The 33P signal intensity distribution pattern for gene expression was similar to that of Yale and Bohnert (67); however, overall levels of expression were slightly lower, resulting in a higher number of genes with background intensities. Previous results have shown that signal intensities produced using total RNA isolated from laboratory strains grown under laboratory conditions are higher than those for industrial strains (25). This probably reflects the different nature of total RNA isolated from industrial strains experiencing harsh industrial conditions. Similar experiences have been reported when RNA is isolated from yeast under starvation conditions (22, 64). While this may have led to changes in expression of some genes not being identified, over 100 genes were clearly induced in the first hour of the fermentation (Table 1). Independent verification of the data by Northern analysis and the statistically significant presence of the ergosterol biosynthesis and redox maintenance gene clusters confirmed the validity of the results.

Apart from the nine genes encoding proteins directly involved in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway, genes implicated indirectly in its biosynthesis were also induced. The ROX1 gene encodes a transcriptional regulator that represses the expression of a number of hypoxic genes, including ERG11 and OLE1 (69). These genes were highly induced in the initial stages of the fermentation, and the reason for induction of ROX1 could be to modulate their high level of expression. Another gene that has been linked to sterol metabolism is the NADPH dehydrogenase encoded by OYE2 (57). Although many of the steps of ergosterol biosynthesis require NADPH dehydrogenase activity, the specific manner in which Oye2p is involved in sterol metabolism is unknown. The sterol pathway also produces farnesyl pyrophosphate, an intermediate that is the starting point for synthesis of several essential metabolites, including heme (62). The first step of this pathway is catalyzed by a 5-aminolevulinate synthase encoded by the HEM1 gene (61), which was induced under these conditions. Deletion of this gene results in a mutant that is unable to produce ergosterol and requires its addition, as well as a source of unsaturated fatty acid and cysteine to support growth (24, 35). This is not surprising, since heme is required for the enzymatic activities of Erg3p, Erg5p, Erg11p, and Ole1p (43, 59), highlighting the possible importance of heme biosynthesis in the initial fermentation period.

The induction of the ergosterol genes resulted in increased cellular ergosterol levels from the initial depleted levels (Fig. 2). This correlated with previous results showing that cells entering industrial fermentations are depleted for ergosterol (9) and that, in the presence of oxygen, ergosterol starvation induces expression of the early ERG genes (19, 52). Ergosterol has been shown to have vital functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells affecting membrane fluidity and permeability and providing the “sparking function” that is thought to be involved in the progression into the G1 phase of the cell cycle (5, 15, 33). It has been proposed that the steps catalyzed by Erg3p and Erg6p are essential for the sparking function (15, 34, 50). Here, the Δerg3 and Δerg6 mutants showed slower rates of metabolic activity than the other erg mutants tested (Fig. 3), similar to the decreased growth rates found by Palermo et al. (45) and Welihinda et al. (63).

The up-regulation of genes in the first hour of fermentation involved in the thioredoxin and GSH cell functions was a strong indication that the cells were experiencing an oxidative stress response. The similarity in kinetics of induction of the ergosterol and oxidative stress response genes pointed to a possible interaction between these two cell functions (Fig. 4). This interaction was confirmed with results showing that yeast mutants unable to produce ergosterol were hypersensitive to oxidative stress (Fig. 5). This is consistent with observations by Bammert and Fostel (4) that perturbation of ergosterol biosynthesis heightened an oxidative stress response in S. cerevisiae. Additionally Schmidt et al. (51) suggested that proper ergosterol biosynthesis may be involved in cellular protection against oxidative stress, since Δerg3 mutants are sensitive to paraquat and H2O2. This relationship may also explain why the Δerg4 and Δerg5 mutants had a lag in the onset of metabolic activities but no change in the final rate of gas production compared to the wild type (Fig. 3). This indicates that the altered sterols [ergosta-5,7,22,24 (28)-trienol and ergosta-5,7,24 (28)-trienol] produced as a result of the ERG4 and ERG5 deletions can efficiently replace the ergosterol requirement for metabolic activity. Palermo et al. (45) also showed that these erg mutants had a lag in growth but a growth rate similar to that of the wild type. The lag for these erg mutants may reflect the decreased ability to adapt efficiently to the oxidative stress encountered when cells are placed into industrial wort.

These observations concerning changes in expression of ergosterol genes and its production are very relevant in the industrial context. For example, there is a difference in growth rate between erg mutants and the wild type, which was greater when the sugar concentration of the medium was increased from 2% to 5% (45). This apparent osmotic stress effect implies the involvement of ergosterol in osmotolerance, and it may therefore be a factor in the success of high-gravity brewing techniques. This is further highlighted by genetic analyses showing that high osmolarity represses the expression of genes involved in the production of sterols (ERG3, -6, -11, and -25) and unsaturated fatty acids (OLE1) (48). The addition of sterols and unsaturated fatty acids has also been shown to provide cells with protection against the stresses caused by acid washing and pitching into high-gravity fermentations (11, 13). Sterol management and osmotolerance may also be implicated in the observed reduction in yeast longevity. When yeast cells are repitched from very-high-gravity fermentations, it has been shown that there is a decrease in viability over the first 12 h of fermentation with elevated wort gravity (12, 14). Oxygenation of wort at pitching is important for sterol and lipid metabolism, yeast performance, and beer flavor (28). The vital importance of oxygenation for ergosterol and unsaturated fatty acid synthesis is highlighted by the observation that the requirement for oxygen disappears when these compounds are added to wort (11, 13).

The presence of oxygen can also cause the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within yeast, causing damage to cellular components (56, 66). These results emphasize the importance for tight control of aeration in industrial fermentations. High levels of oxygen caused by overaeration can decrease the expression of ERG11 (ergosterol biosynthesis) and OLE1 (unsaturated fatty acid synthesis) to very low levels (68), further escalating the effects of oxidative stress. Using electron spin resonance methods, Uchido and Ono (60) found that the oxidative capacity of the final beer product was highest following fermentation regimes using lower oxygen levels during the initial stages of the fermentation. Apart from oxygenation regulation, high-gravity brewing techniques have the additional problem of decreased ergosterol biosynthesis due to high osmolarity. Perhaps this problem could be reduced by a modification of the procedure described by Devuyst et al. (18). Preincubation of cropped yeast in low-oxygenated wort with a low concentration of sugar before pitching would provide a yeast higher in sterol and unsaturated fatty acid levels and subsequently better able to endure the rigors of high-gravity wort brewing.

Here we have shown that yeast gene expression measured by genome-wide expression analysis during industrial fermentation processes can provide an effective way to identify and monitor conditions that have a relevant effect on yeast performance and hence fermentation efficiency.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an Australian Research Council Research Linkage grant and by Carlton & United Breweries.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, M. S., M. Muehlbacher, I. P. Street, J. Proffitt, and C. D. Poulter. 1989. Isopentenyl diphosphate:dimethylallyl diphosphate isomerase. An improved purification of the enzyme and isolation of the gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 264:19169-19175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aranda, A., A. Querol, and M. L. del Olmo. 2002. Correlation between acetaldehyde and ethanol resistance and expression of HSP genes in yeast strains isolated during the biological aging of sherry wines. Arch. Microbiol. 177:304-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attfield, P. V. 1997. Stress tolerance: the key to effective strains of industrial baker's yeast. Nat. Biotechnol. 15:1351-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bammert, G. F., and J. M. Fostel. 2000. Genome-wide expression patterns in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: comparison of drug treatments and genetic alterations affecting biosynthesis of ergosterol. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1255-1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bard, M., N. D. Lees, L. S. Burrows, and F. W. Kleinhans. 1978. Differences in crystal violet uptake and cation-induced death among yeast sterol mutants. J. Bacteriol. 135:1146-1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell, P. J. L., V. J. Higgins, and P. V. Attfield. 2001. Comparison of fermentative capacities of industrial baking and wild-type yeasts of the species Saccharomyces cerevisiae in different sugar media. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 32:224-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Böcking, T., K. D. Barrow, A. G. Netting, T. C. Chilcott, H. G. Coster, and M. Hofer. 2000. Effects of singlet oxygen on membrane sterols in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:1607-1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, P. O., and D. Botstein. 1999. Exploring the new world of the genome with DNA microarrays. Nat. Genet. 21:33-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callaerts, G., D. Iserentant, and H. Verachtert. 1993. Relationship between trehalose and sterol accumulation during oxygenation of cropped yeast. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 51:75-77. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmel-Harel, O., R. Stearman, A. P. Gasch, D Botstein, P. O. Brown, and G. Storz. 2001. Role of thioredoxin reductase in the Yap1p-dependent response to oxidative stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 39:595-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casey, G. P., C. A. Magnus, and W. M. Ingledew. 1983. High-gravity brewing: nutrient enhanced production of high concentrations of ethanol by brewing yeast. Biotechnol. Lett. 5:429-434. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casey, G. P., and W. M. Ingledew. 1983. High-gravity brewing: influence of pitching rate and wort gravity on early yeast viability. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 41:148-152. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casey, G. P., C. A. Magnus, and W. M. Ingledew. 1984. High-gravity brewing: effects of nutrition on yeast composition, fermentative ability, and alcohol production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48:639-646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cunningham, S., and G. G. Stewart. 1998. Effects of high-gravity brewing and acid washing on brewer's yeast. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 56:12-18. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahl, C., H. P. Biemann, and J. Dahl. 1987. A protein kinase antigenically related to pp60 src possibly involved in yeast cell cycle control: positive in vivo regulation of sterol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:4012-4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daum, G., N. D. Lees, M. Bard, and R. Dickson. 1998. Biochemistry, cell biology and molecular biology of lipids of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:1471-1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Day, R. E., P. J. Rogers, I. W. Dawes, and V. J. Higgins. 2002. Molecular analysis of maltotriose transport and utilization by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5326-5335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devuyst, R., D. Dyon, C. Ramos-Jeunehomme, and C. A. Masschelein. 1991. Oxygen transfer efficiency with a view to the improvement of lager yeast performance and beer quality, p. 377-384. In Proceedings of the 23rd European Brewing Congress, Lisbon, Portugal.

- 19.Dimster-Denk, D., and J. Rine. 1996. Transcriptional regulation of a sterol-biosynthetic enzyme by sterol levels in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:3981-3989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunas, F. 1988. Multi Fermentation Screening System (MFSS): computerised simultaneous evaluation of carbon dioxide production in twenty yeasted broths or doughs. J. Microbiol. Methods 8:303-314. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emandes, J. R., J. W. Williams, I. Russell, and G. G. Stewart. 1993. Respiratory deficiency in brewing yeast strains—effects on fermentation, flocculation and beer flavour components. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 51:16-20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuge, E. K., E. L. Braun, and M. Werner-Washburne. 1994. Protein synthesis in long-term stationary-phase cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 176:5802-5813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gasch, A. P., P. T. Spellman, C. M. Kao, O. Carmel-Harel, M. B. Eisen, G. Storz, D. Botstein, and P. O. Brown. 2000. Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:4241-4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Gene Ontology Consortium. 2001. Creating the gene ontology resource: design and implementation. Genome Res. 11:1425-1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gollub, E. G., K. P. Liu, J. Dayan, M. Adlersberg, and D. B. Sprinson. 1977. Yeast mutants deficient in heme biosynthesis and a heme mutant additionally blocked in cyclization of 2,3-oxidosqualene. J. Biol. Chem. 252:2846-2854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins, V. J., A. D. Oliver, R. E. Day, I. W. Dawes, and P. J. Rogers. 2001. Application of genome-wide transcriptional analysis to identify genetic markers useful in industrial fermentations, p. 1-10. In Proceedings of the 28th European Brewing Congress, Budapest, Hungary.

- 26.Hodges, P. E., A. H. Z. McKee, B. P. Davis, W. E. Payne, and J. I. Garrels. 1999. Yeast Protein Database (YPD): a model for the organization and presentation of genome-wide functional data. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:69-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmgren, A. 1979. Glutathione dependent synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides. J. Biol. Chem. 254:3664-3671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jahnke, L., and H. P. Klein. 1983. Oxygen requirement for formation and activity of the squalene epoxidase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 155:488-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jamieson, D. J. 1998. Oxidative stress responses of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:1511-1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jazwinski, S. M. 1990. Aging and senescence of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 4:337-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kornblatt, J. A., and H. Rudney. 1971. Two forms of acetoacetyl coenzyme A thiolase in yeast. I. Separation and properties. J. Biol. Chem. 246:4417-4423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kosugi, A., Y. Koizumi, F. Yanagida, and S. Udaka. 2001. MUP1, high affinity methionine permease, is involved in cysteine uptake by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 65:728-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lees, N. D., M. Bard, M. D. Kemple, R. A. Haak, and F. W. Kleinhans. 1979. ESR determination of membrane order parameter in yeast sterol mutants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 553:469-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lorenz, R. T., W. M. Casey, and L. W. Parks. 1989. Structural discrimination in the sparking function of sterols in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 171:6169-6173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maclean, K. N., M. Janosik, J. Oliveriusova, V. Kery, and J. P. Kraus. 2000. Transsulfuration in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is not dependent on heme: purification and characterization of recombinant yeast cystathionine beta-synthase. J. Inorg. Biochem. 81:161-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mewes, H. W., et al. 2000. MIPS: a database for genomes and protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:37-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moradas-Ferreira, P., V. Costa, P. Piper, and W. Mager. 1996. The molecular defences against reactive oxygen species in yeast. Mol. Microbiol. 19:651-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morrison, K. B., and A. Suggett. 1983. Yeast handling, petite mutants and lager flavour. J. Inst. Brew. 89:141-142. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohtake, Y., and S. Yabuchi. 1991. Molecular cloning of the gamma-glutamylcysteine synthase gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 7:953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ono, B.-I., Y.-I. Shirahige, A. Nanjoh, N. Andou, H. Ohue, and Y. Ishino-Arao. 1988. Cysteine biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: mutation that confers cystathionine β-synthase deficiency. J. Bacteriol. 170:5883-5889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ono, B.-I., K. Tanaka, K. Naito, C. Heike, S. Shinoda, S. Yamamoto, S. Ohmori, T. Oshima, and A. Toh-E. 1992. Cloning and characterization of the CYS3 (CYI1) gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 174:3339-3347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park, S. G., M. K. Cha, W. Jeong, and I. H. Kim. 2000. Distinct physiological functions of thiol peroxidase isoenzymes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 275:5723-5732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parks, L. W. 1978. Metabolism of sterols in yeast. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 6:301-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parks, L. W., C. D. K. Bottema, R. J. Rodriguez, and T. A. Lewis. 1985. Yeast sterols: yeast mutants as tools for the study of sterol metabolism. Methods Enzymol. 111:333-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palermo, L. M., F. W. Leak, S. Tove, and L. W. Parks. 1997. Assessment of the essentiality of ERG genes late in ergosterol biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 32:93-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perez-Torrado, R., P. Carrasco, A. Aranda, J. Gimeno-Alcaniz, J. E. Perez-Ortin, E. Matallana, and M. L. del Olmo. 2002. Study of the first hours of microvinification by the use of osmotic stress-response genes as probes. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 25:153-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Powell, C. D., S. M. Van Zandycke, D. E. Quain, and K. A. Smart. 2000. Replicative ageing and senescence in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the impact on brewing fermentations. Microbiology 146:1023-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rep, M., M. Krantz, J. M. Thevelein, and S. Hohmann. 2000. The transcriptional response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to osmotic shock. Hot1p and Msn2p/Msn4p are required for the induction of subsets of high osmolarity glycerol pathway-dependent genes. J. Biol. Chem. 275:8290-8300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robinson, M. D., J. Grigull, N. Mohammad, and T. R. Hughes. 20May2003, posting date. FunSpec: a web-based cluster interpreter for yeast. BMC Bioinformatics 3:35-40. [Online.] http://funspec.med.utoronto.ca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Rodriguez, R. J., and L. W. Parks. 1983. Structural and physiological features of sterols necessary to satisfy bulk membrane and sparking requirements in yeast sterol auxotrophs. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 225:861-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmidt, C. L., M. Grey, M. Schmidt, M. Brendel, and J. A. Henriques. 1999. Allelism of Saccharomyces cerevisiae genes PSO6, involved in survival after 3-CPs+UVA induced damage, and ERG3, encoding the enzyme sterol C-5 desaturase. Yeast 15:1503-1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Servouse, M., and F. Karst. 1986. Regulation of early enzymes of ergosterol biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. J. 240:541-547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sinclair, D., K. Mills, and L. Guarente. 1998. Aging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:533-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soustre, I., P. H. Dupuy, S. Silve, F. Karst, and G. Loison. 2000. Sterol metabolism and ERG2 gene regulation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 470:102-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spencer, J. F. T., D. M. Spencer, and R. Miller. 1983. Inability of petite mutants of industrial yeasts to utilize various sugars and a comparison with the ability of the parent strains to ferment the same sugars microaerophilically. J. Biosci. 38:405-407. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Storz, G., M. F. Christman, H. Sies, and B. N. Ames. 1987. Spontaneous mutagenesis and oxidative damage to DNA in Salmonella typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:8917-8921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stott, K., K. Saito, D. J. Thiele, and V. Massey. 1993. Old yellow enzyme. The discovery of multiple isozymes and a family of related proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 268:6097-6106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Terada, T. 1994. Thioltransferase can utilize cysteamine as same as glutathione as a reductant during the restoration of cystamine-treated glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 34:723-727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Turi, T. G., and J. C. Loper. 1992. Multiple regulatory elements control expression of the gene encoding the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cytochrome P450, lanosterol 14 alpha-demethylase (ERG11). J. Biol. Chem. 267:2046-2056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Uchido, M., and M. Ono. 2000. Technological approach to improve beer flavor stability: adjustment of the wort aeration in modern fermentation systems using the electron spin resonance method. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 58:30-37. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Urban-Grimal, D., and R. Labbe-Bois. 1981. Genetic and biochemical characterization of mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae blocked in six different steps of heme biosynthesis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 183:85-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weinstein, J. D., R. Branchaud, S. I. Beale, W. J. Bement, and P. R. Sinclair. 1986. Biosynthesis of the farnesyl moiety of heme a from exogenous mevalonic acid by cultured chick liver cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 245:44-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Welihinda, A. A., A. D. Beavis, and R. J. Trumbly. 1994. Mutations in LIS1 (ERG6) gene confer increased sodium and lithium uptake in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1193:107-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Werner-Washburne, M., E. L. Braun, M. E. Crawford, and V. M. Peck. 1996. Stationary phase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 19:1159-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Winzeler, E. A., et al. 1999. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science 285:901-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wolff, S. P., A. Garner, and R. T. Dean. 1986. Free radicals, lipids and protein degradation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 11:27-31. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yale, J., and H. J. Bohnert. 2001. Transcript expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae at high salinity. J. Biol. Chem. 276:15996-16007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zitomer, R. S., and C. V. Lowry. 1992. Regulation of gene expression by oxygen in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 56:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zitomer, R. S., P. Carrico, and J. Deckert. 1997. Regulation of hypoxic gene expression in yeast. Kidney Int. 51:507-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]