Abstract

The ability to chemically modify the surfaces of viruses and virus-like particles makes it possible to confer properties that make them potentially useful in biotechnology, nanotechnology and molecular electronics applications. RNA phages (e.g. MS2) have characteristics that make them suitable scaffolds to which a variety of substances could be chemically attached in definite geometric patterns. To provide for specific chemical modification of MS2's outer surface, cysteine residues were substituted for several amino acids present on the surface of the wild-type virus particle. Some substitutions resulted in coat protein folding or stability defects, but one allowed the production of an otherwise normal virus-like particle with an accessible sulfhydryl on its surface.

Background

The ability of viruses to self-assemble into nanoscale particles of discrete size and definite geometry gives them potential utility in a variety of nano- and biotechnology applications. Efforts to adapt icosahedral virus particles for use as templates for materials synthesis, as platforms for the multivalent presentation of ligands, and even as possible molecular electronic components have been described recently [1-7]. Work reported to date has made use of Cowpea Chlorotic Mottle Virus [1-4] and Cowpea Mosaic Virus [5-7]. Experiments that explore the utility of the RNA bacteriophage MS2 for similar purposes are presented here.

RNA bacteriophages represent attractive systems for engineering new properties into viruses and virus-like particles. Each RNA phage particle is comprised of 180 copies of a single coat protein polypeptide about 130 amino acids in length, one copy of the maturase protein, and one molecule of viral genome RNA. The coat protein itself possesses all the information needed for assembly into an icosahedron with a diameter of about 25 nm. This means that virus capsids can be produced by expression of the coat gene from a plasmid in E. coli without the need for other viral components. The coat protein dimer, the structural unit from which capsids are assembled, possesses a high-affinity binding site for a specific RNA hairpin. Since this hairpin can function as a packaging signal, it is straight-forward to engineer the encapsidation of an arbitrarily chosen RNA by fusing it to this so-called pac site and expressing it in an E. coli strain that also produces coat protein [8].

RNA phage coat proteins are amenable to facile genetic manipulation. It is, of course, a simple matter to introduce any desired amino acid substitution by site-directed mutagenesis of the coat protein cDNA clone, but systems also exist that facilitate random mutagenesis and selection of coat mutants having altered RNA binding [9] and particle assembly [10] properties. A simple assay for correct particle assembly [11] makes it easy to screen out those mutants that acquire undesired defects in protein folding or assembly. Moreover, because coat proteins produced from a plasmid in E. coli are fully competent for particle assembly, changes in coat protein structure that are incompatible with the normal virus life cycle can be easily introduced and propagated. This is an advantage not readily available in some other systems. Moreover, cDNA clones of viral RNA are infectious, making it easy to produce viable recombinant viruses that incorporate any mutation that does not interfere with virus viability. Both virus and virus-like particles are readily produced in large quantities and high purity.

High resolution x-ray structures are available for a number of RNA phages, including MS2 [12-18], so that desirable sites for modification can be identified easily. Here I describe the production of a bacteriophage MS2 coat protein mutant that displays a reactive thiol on the surface of the virus-like particle. Thiols are among the most useful functional groups found in proteins. It can bind a variety of metals and reacts with a large collection of organic reagents, thus making cysteines obvious targets for protein modification reactions. Wild-type MS2 coat protein contains two cysteines, but they are sequestered in the interior of the protein where they should be relatively unreactive. The introduction of an accessible cysteine on the surface of the MS2 capsid therefore should create the opportunity for multivalent display of a large number of different potential ligands on its surface.

Results

Introduction of surface cysteines and their effects on coat protein structure

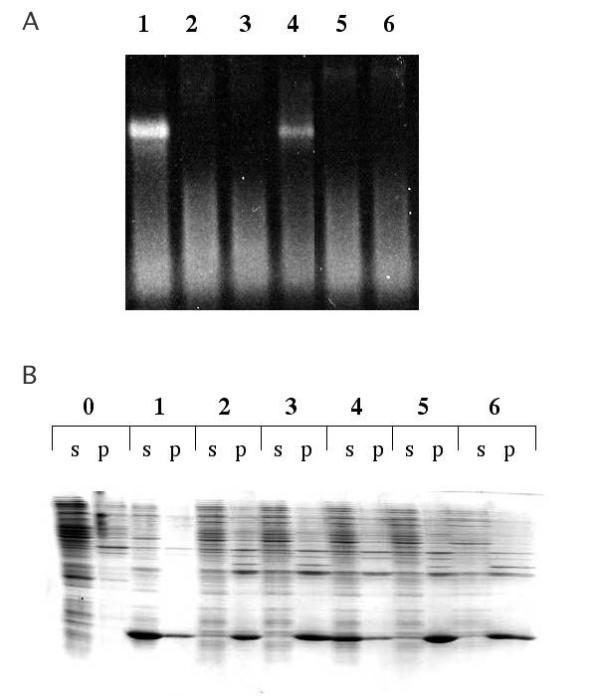

Based on their accessibility on the surface of the viral capsid, five different amino acids of MS2 coat protein were selected initially for cysteine substitution (Figure 1). Three of the five (glycine13, glycine14, and threonine15) are located in the so-called AB-loop, a short β-turn that connects the A and B β-strands of coat protein. The other two (aspartic acid114 and glycine115) reside in a loop connecting the two coat protein α-helices. Each of these five amino acids was converted to cysteine by site-directed mutagenesis and the mutant genes were cloned in the plasmid called pET3d [19] and introduced into E. coli strain BL21(DE3/pLysS for over-expression. Each mutant was screened by SDS gel electrophoresis for the ability to produce more or less normal amounts of coat protein in the soluble fraction of cell lysates, and by agarose gel electrophoresis under native conditions for correct assembly of a virus-like particle. These criteria allow us to determine whether the mutants produce properly folded coat proteins. Four of the five mutants, G13C, G14C, D114C and G115C, failed these tests (Figure 2). In these cases no virus-like particles were detected and the coat proteins were found predominantly in the insoluble fraction of cell lysates.

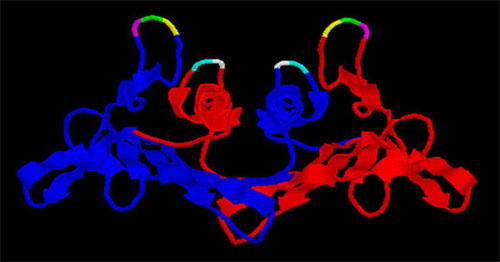

Figure 1.

A view of the MS2 coat protein dimer with its two polypeptide chains shown as blue and red ribbons. The positions of amino acids altered in this study by site-directed mutagenesis are shown as yellow (glycine13), green (glycine14), magenta (threonine15), cyan (glycine113) and white (aspartic acid114). For details of the structure of MS2 coat protein see refs. 12 and 13.

Figure 2.

A. Agarose gel electrophoresis of the soluble fractions of lysates of E. coli cells producing the wild-type (WT) and each of the mutant coat proteins (lanes 1–6). Since the particles contain host cell-derived RNA, they can be stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV illumination. Cellular nucleic acids are also visible as a faster-running smear. Lane 1 – wild-type, lane 2 – G13C, lane 3 – G14C; lane 4 – T15C, lane 5 – G113C, lane 6 – D114C. B. SDS gel electrophoresis of protein extracted from the same cells. Here are shown the contents of both the soluble (s) and pellet (p) fractions of crude cell lysates. Samples are labeled as in A, except for the addition of lane 0, which is a control that produces no coat protein.

In past work it has frequently been possible to suppress the effects of mutations on MS2 coat protein folding/stability by incorporating them into so-called single-chain dimers. Because of the proximity of the N-terminus of one subunit of the coat protein dimer to the C-terminus of the other subunit, it is possible to genetically fuse them into a single polypeptide chain. Covalently linking the two monomers in this manner makes the dimer relatively resistant to the destabilizing effects of many amino acid substitutions and even of peptide insertions [20-23]. In an effort to revert their effects on coat protein structure, the G13C, G14C, D114C and G115C mutations were incorporated into single-chain dimer constructs. However, in none of these cases was the ability to produce active coat protein restored (results not shown).

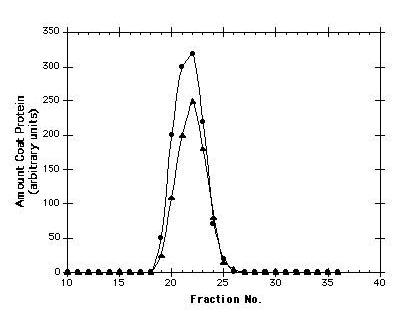

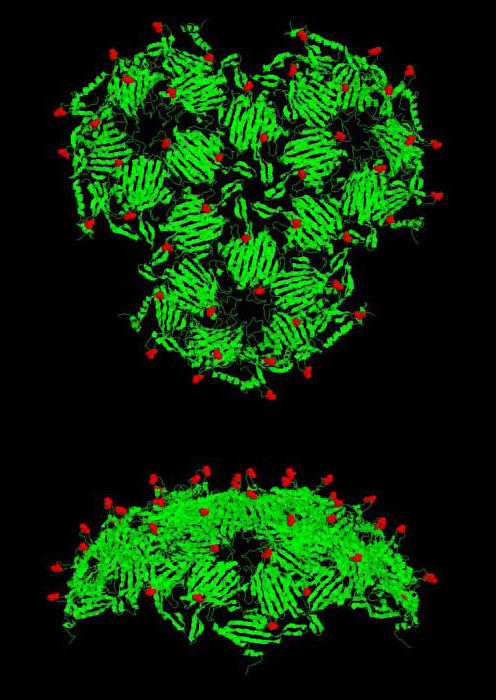

In contrast to the destabilizing substitutions, the T15C mutant (where threonine15 is replaced by cysteine) produced significant quantities of soluble coat protein that assembled into particles with the same electrophoretic mobility as wild-type virus. Assembly into a virus-sized particle was verified by the behavior of the T15C mutant upon chromatography in Sepharose CL-4B. As seen in Figure 3, wild-type MS2 and the T15C mutant particles both eluted in a discrete, symmetric peak at the same position. Figure 4 shows the structure of a portion of the viral capsid with the location of residue 15 indicated in red. It illustrates how the existence of the T15C mutant should make it possible to attach chemically a variety of substances in a defined geometric array on outside of the particle. Introduction of cysteine at other sites would allow variations in this pattern, each of them adhering to the constraints of icosahedral geometry, but allowing different relative spacings of the functional group.

Figure 3.

Elution profiles of wild-type and T15C virus-like particles from a Sepharose CL-4B column. The presence of coat protein in individual fractions was determined by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by staining with coomassie blue and densitometry. Void volume is at fraction 11. A protein roughly the size of the coat protein monomer (lysozyme, MW about 14,000) elutes at position 33.

Figure 4.

Two views of a portion of the surface of the viral particle showing the exposure of threonine15 and the pattern of its display. Polypeptide chains are shown as ribbons. The position of threonine15 is indicated in red space-fill. Note that the structure shown here (downloadable as 1GAV.pdb from http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/, the protein data bank website) is actually that of GA, a close MS2 relative with a highly similar structure [18]

Accessibility and reactivity of the new cysteine

T15C virus-like particles were purified from E. coli, using methods that included gel filtration chromatography on Sepharose CL-4B and that were described previously for the wild-type virus-like particle [9]. Note that although the reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT) was present in the cell lysis solution, it was absent from the chromatography buffer. Therefore, when column-purified capsids were concentrated by ultracentrifugation, it was under conditions that allow the formation of disulfide bonds. Upon attempting to redissolve the pelleted T15C particles it was immediately apparent that their behavior was different from wild-type. Whereas wild-type particles dissolve readily in water, the mutant capsids were insoluble. Agarose gel electrophoresis also indicated the formation of large aggregates, because mutant particles failed to enter the gel (Figure 5). Treatment with 10 mM DTT led to the immediate dissolution (within a few minutes) of the aggregate and to the restoration of wild-type electrophoretic behavior. Thus, concentration of the capsids under non-reducing conditions allowed efficient inter-particle disulfide cross-linking. At intermediate DTT concentrations, gel electrophoresis produced a ladder of species representing intermediately aggregated states, i.e. capsid dimers, trimers, tetramers and so forth. When the aggregates were subjected to SDS gel electrophoresis in the absence of reducing agent (with NEM included to prevent thiol-disulfide interchange during sample preparation) about 3% of the coat protein was present in the form of a disulfide linked dimer, consistent with the idea that each capsid in the aggregate is cross-linked on average to about 5 others (data not shown).

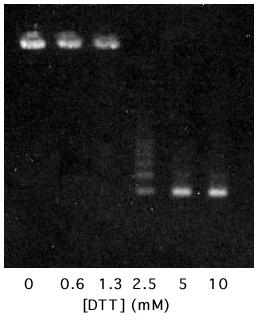

Figure 5.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of MS2-T15C virus-like particles treated with DTT at the indicated concentrations. The material on the left is extensively aggregated and does not enter the gel. Material on the right is fully reduced and possesses the electrophoretic behavior characteristic of MS2 itself (see Figures 2 and 6).

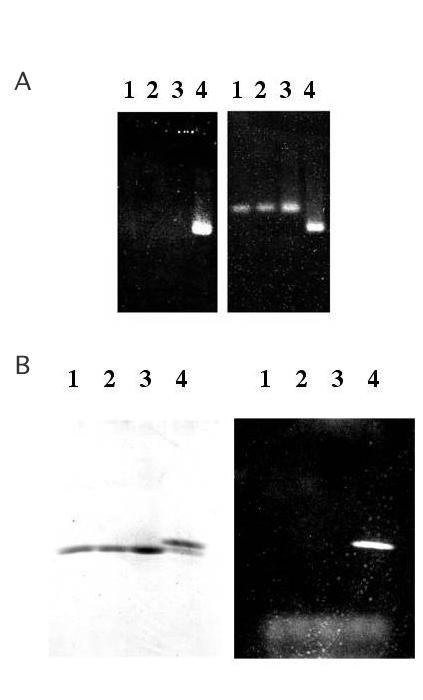

The accessibility of the new cysteine is further illustrated by its reaction with thiol-specific chemical reagents. For simplicity only the results obtained when capsids are reacted with fluorescein-5-maleimide are shown here, but similar results were obtained from reaction with 5,5'-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) to form the 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoyl derivative [24], by reaction with Na2SO3 in the presence of DTNB [25] to produce the thiosulfonate derivative, and when reacted with iodoacetic acid to form the carboxymethyl derivative. Wild-type and T15C capsids were reacted with fluoroscein-5-maleimide under conditions described in Materials and Methods and the products were subjected to electrophoresis in agarose gels and photographed under UV illumination both before and after staining with ethidium bromide, which gives an orange fluorescence to all the capsids because of the RNA each contains. Reaction with fluorescein-5-maleimide imparts green fluorescence to the mutant particle (Figure 6A). In addition, its electrophoretic mobility increases, consistent with the addition of negative charges to the capsid (fluorescein has a carboxyl group). The modification is specific for the T15C mutant – wild-type MS2 remains unmodified – and is abolished when the reagent is inactivated by prior addition of DTT to the reaction. When subjected to electrophoresis in SDS-polyacrylamide gels a single fluorescent product is observed for the T15C mutant (Figure 6B). Staining of the gel with coomassie blue shows that attachment of fluorescein alters the mobility of coat protein, allowing an estimation of the extent of its modification. Clearly, the great majority (about 80–90%) of the T15C coat protein undergoes reaction under these conditions. Longer reaction times (up to 1.5 hours) at a higher temperature (37°C) did not alter this pattern. Failure to modify the wild-type coat protein indicates that the other cysteines (residues 46 and 101) are not detectably accessible for reaction under these conditions.

Figure 6.

A. Agarose gel electrophoresis of capsids unstained (on the left) and stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under UV illumination. Lane 1 is unreacted MS2, lane 2 is MS2 modified by reaction with fluorescein-5-maleimide, lane 3 is unreacted T15C, lane 4 is T15C reacted with fluorescein-5-maleimide. B. SDS gel electrophoresis of the same samples shown in A. On the left is the gel stained with coomassie brilliant blue and at right it is illuminated in the UV.

Discussion

Single amino acid substitutions frequently have global effects on protein folding and stability. Considering their locations in the coat protein structure it is not surprising that some substitutions of AB loop residues disrupted folding. The loop makes a tight turn and the glycines present at positions 13 and 14 are probably needed to prevent the crowding that results when amino acids with bulkier side chains are introduced here. Moreover, the defects caused by the G13C and G14C substitutions must be fairly severe, since they are not reverted by their incorporation into single-chain coat protein dimers. Genetic fusion of the subunits of the dimer was shown previously to revert the destabilizing effects of variety of mutations, including a wide range of amino acid substitutions at different locations on the β-sheet [21,22], temperature-sensitive mutations occurring at numerous sites through-out the structure (unpublished observations), and even insertions into the AB-loop sequence itself [23]. The T15C mutation, on the other hand is tolerated structurally. Cysteine is a slightly smaller amino acid than the threonine it replaces and so would not be expected to introduce stereochemical difficulties of the sort that likely explain the G13C and G14C defects.

It is less obvious why the substitutions at residues aspartic acid114 and glycine115 lead to folding-defects, but these residues also are involved in a turn of the polypeptide, this one connecting the two coat protein alpha-helices. The severity of the defects conferred by the cysteines introduced here is also indicated by the failure to revert them in single-chain dimers.

As these results illustrate, amino acid substitutions can disrupt protein folding and stability with an annoyingly high frequency. It should be noted, though, that at least two different strategies are available for efforts to render the substitutions tolerable. The first is to create single-chain dimers of the mutant proteins [20-23]. Although this was ineffective in the cases of the four defective mutants described here, it has in the past proven an efficient and simple means of reverting coat protein folding defects and will likely be useful for many of the other defects one might encounter. Moreover, since single-chain dimers allow independent control of the amino acid sequences in the two halves of the "dimer", it provides a means to alter by one-half the number of thiols on the virus surface, giving an added level of control over the density of modifiable sites. A second strategy for reversion of folding/stability defects is to isolate mutations at second sites that suppress those defects. A gel diffusion method that allows one to distinguish bacterial colonies that produce soluble, properly assembled coat protein from those that do not has been described elsewhere [10].

The sites modified in this study were chosen because they are highly exposed on the virus surface, but a number of other sites in coat protein are also located in potentially suitable positions, and some of them are likely to be more tolerant of substitution than those tested so far. The capacity to introduce cysteines at alternative positions would allow one to alter the relative geometric arrangement of reactive sites, an additional parameter that should influence the properties of specific modified virus-like particles. The procedure outlined here serves as a guide to the identification of residues whose substitution is tolerated.

Wild-type MS2 coat protein has two cysteines, one at position 46 and the other at 101. Under the conditions used in this study, no evidence that these cysteines were modified by fluoroscein-5-maleimide was observed. This selectivity is a little surprising in view of the previous demonstrations that cysteine46 is somewhat susceptible to reaction with sulfhydryl-specific reagents [26,27] even though, like cysteine101, it is relatively buried within the coat protein tertiary structure. However, those prior studies were conducted using isolated coat protein dimers. Here intact virus-like particles were used. They apparently afford greater protection to cysteine46. Alternatively, because it is bulkier than the reagents used in the previous studies (e.g. N-ethylmaleimide), the fluoroscein-5-maleimide reagent might not as easily gain access to cysteine46.

Conclusions

The ability to chemically modify specific sites on virus particle surfaces is a potentially powerful approach to the production of new materials for biotechnology, nanotechnology and molecular electronics. It makes possible the use of the virus-like particle as a scaffold for the attachment of a large variety of substances including metals, organics, peptides, and nucleic acids in a regular geometric array. Thus, one can think of these virus-like particles as self-assembling and highly regular nanospheres, potentially susceptible to a wide range of chemical modifications at specific surface locations. They may be suitable for use in applications currently employing small spheres constructed by other, less controlled means. The ability to specifically encapsidate and protect arbitrarily chosen RNAs within such particles suggests additional applications. Experiments are currently underway to explore some of the possibilities.

Methods

Mutations were introduced into the MS2 coat sequence using mismatched oligonucleotide primers (from Integrated DNA Technologies) in a PCR-based overlap extension method [28,29]. The mutations were constructed using the following codon changes. G13C (GGC to UGC), G14C (GGA to UGU), T15C AGU to UGU), D114C (GAU to UGU) and G115C (GGA to UGU). The resulting PCR products were cloned as XbaI-BamHI fragments in the T7 expression vector called pET3d [19] thus creating a series of derivatives of the plasmid called pETCT [10]. The nucleotide sequences of each of the mutant coat genes were determined at the UNM Center for Genetics in Medicine. Coat proteins were produced by over-expression in strain BL21(DE3)/pLysS [10,19]. The presence of virus-like particles in crude cell lysates was determined by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels in 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0 as described previously [11]. Coat proteins were purified by methods described in detail elsewhere [9]. These methods include chromatography in Sepharose CL-4B followed by pelleting of the virus from peak fractions by centrifugation at 25,000 rpm in the SW28 rotor overnight. Electrophoresis of purified virus-like particles was conducted in 1% agarose and 40 mM Tris-acetate, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0. Production of crude cell lysates, their separation into soluble and insoluble fractions, and their analysis by SDS gel electrophoresis have been also detailed in previous reports [10,11].

Fluorescein labeling was conducted by reaction for 30 min. at room temperature in 20ul of 50 mM potassium phosphate pH7.0, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM fluorescein-5-maleimide (from Helix, Inc.). Proteins were present at concentrations in the 0.5 to 2 mg/ml range. Reactions were terminated by the addition of DTT to a concentration of 50 mM. Unreacted controls were performed by adding DTT to the reaction before the protein. The products were subjected to electrophoresis in agarose gels under native conditions in 40 mM Tris-acetate, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, and in SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Fluoresceinated products were detected by photography under UV illumination.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Air Force Research Laboratory.

References

- Douglas T, Young M. Virus Particles as Templates for Materials Synthesis. Adv Mater. 1999;11:679–681. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4095(199906)11:8<679::AID-ADMA679>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas T, Strable E, Willits D, Aitouchen A, Libera M, Young M. Protein Engineering of a Viral Cage for Constrained Nanomaterials Synthesis. Adv Mater. 2002;14:415–418. doi: 10.1002/1521-4095(20020318)14:6<415::AID-ADMA415>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillitzer E, Willits D, Young M, Douglas T. Chemical modification of a viral cage for multivalent presentation. Chem Comm. 2002:2390–2391. doi: 10.1039/b207853h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas T, Young MJ. Host-guest encapsulation of materials by assembled virus protein cages. Nature. 1998;393:152–155. doi: 10.1038/30211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Kaltgrad E, Lin T, Johnson JE, Finn MG. Natural Supramolecular Building Blocks: Wild-Type Cowpea Mosaic Virus. Chemistry and Biology. 2002;9:805–811. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(02)00165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Lin T, Johnson JE, Finn MG. Natural Supramolecular Building Blocks: Cysteine-Added Mutants of Cowpea Mosaic Virus. Chemistry and Biology. 2002;9:813–819. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(02)00166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Lin T, Tang L, Johnson JE, Finn MG. Icosahedral Virus particles as Addressable Nanoscale Building Blocks. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:459–462. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020201)41:3<459::AID-ANIE459>3.3.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett G, Peabody DS. Encapsidation of Heterologous RNAs by Bacteriophage MS2 Coat Protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4621–4626. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.19.4621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody DS. Translational Repression by Bacteriophage MS2 Coat Protein Expressed From a Plasmid: A System for Genetic Analysis of a Protein-RNA Interaction. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:5684–5689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody DS, Al-Bitar L. Isolation of Viral Coat Protein Mutants With Altered Assembly and Aggregation Properties. Nucleic Acids Research. 2001;29:e113. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody DS. The RNA-binding site of bacteriophage MS2 coat protein. EMBO J. 1993;12:595–600. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valegard K, Liljas L, Fridborg K, Unge T. The three-dimensional structure of the bacterial virus MS2. Nature. 1990;345:36–41. doi: 10.1038/345036a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golmohammadi R, Valegard K, Fridborg K, Liljas L. The refined structure of bacteriophage MS2 at 2.8A resolution. J Mol Bio. 1993;234:620–639. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golmohammadi R, Fridgorg K, Bundule M, Valegard K, Liljas L. The crystal structure of bacteriophage Qβ at 3.5A resolution. Structure. 1996;4:543–554. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tars K, Fridborg K, Bundule M, Liljas L. The Three-Dimensional Structure of Bacteriophage PP7 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa at 3.7A Resolution. Virology. 2000;272:331–337. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljas L, Fridborg K, Valegard K, Bundule M, Pumpens P. Crystal structure of bacteriophage fr capsids at 3.5A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1994;244:279–290. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni C-Z, White CA, Mitchell RS, Wickersham J, Ramadurgam K, Peabody DS, Ely KR. Protein Science. 1996;5:2485–2493. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tars K, Bundule M, Fridborg K, Liljas L. The Crystal Structure of Bacteriophage GA and a Comparison of Bacteriophages Belonging to the Major Groups of Escherichia coli Leviviruses. J Mol Biol. 1997;271:759–773. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studier FW, Rosenberg AH, Dunn JJ, Dubendorff JW. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody DS, Lim F. Complementation of RNA binding site mutations in MS2 coat protein heterodimers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2352–2359. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.12.2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody DS, Chakerian A. Asymmetric Contribution to RNA Binding by the Thr45 Residues of the MS2 Coat Protein Dimer. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25403–25410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell AJ, Peabody DS. Asymmetric interactions in the adenosine-binding pockets of MS2 coat protein. BMC Molecular Biology. 2001;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody DS. Subunit Fusion Confers Tolerance to Peptide Insertions in a Virus Coat Protein. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;347:85–92. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellman GL. Tissue Sulfhydryl Groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody DS, Ely KR, Edmundson AB. Obligatory hybridization of heterologous immunoglobulin light chains into covalently linked dimers. Biochemistry. 1980;19:2827–2834. doi: 10.1021/bi00554a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berzin VM, Tsimanis AY, Gren EY, Aagorski W, Szafranski P. Effect of Chemical Modification of Cysteine Residues in the Phage MS2 Coat Protein on the Repressor Complex Formation With MS2 RNA. Bioorg Khim. 1981;7:894–899. [Google Scholar]

- Romaniuk P, Uhlenbeck OC. Nucleoside and Nucleotide Inactivation of R17 Coat Protein: Evidence for a Transient Covalent RNA-Protein bond. Biochemistry. 1985;24:4239–4244. doi: 10.1021/bi00336a064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi R, Krummel B, Saiki RK. A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:7357–7367. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.15.7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]