Abstract

Hemangiopericytoma is a rare and characteristically hypervascular tumour. We report a case of hepatic metastases of hemangiopericytoma for which there was correlative imaging by ultrasonography, ultrasonography with second-generation contrast agent (BR1), computed tomography, gadolinium-enhanced, Gd-BOPTA-enhanced and ferumoxides-enhanced magnetic resonance, and angiography. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case in which all these modalities were used in the diagnostic evaluation.

Keywords: Hemangiopericytoma, hepatic metastases, contrast-enhanced MRI, contrast-enhanced ultrasonography, angiography

Introduction

Hemangiopericytoma is an unusual highly vascular soft tissue sarcoma of pericytic origin that commonly affects adults in the fifth or sixth decade of life . Complete surgical removal is the treatment of choice for primary tumour, local recurrence and solitary metastasis . Computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and angiography are classically considered the diagnostic modalities of choice for preoperative evaluation and surgical planning . Recently, contrast-enhanced MRI has emerged as a valuable non-invasive technique which provides a rich analysis of the regional vascular properties of a tumour . Ultrasonography (US) with the use of second-generation contrast agent has the potential to increase the detection of hypervascular tumours . We describe the CT, contrast-enhanced MRI, US with second-generation contrast agent, and angiography findings in a patient with hepatic metastases of hemangiopericytoma.

Case report

A 57-year-old man presented with a 1 month history of slowly progressive mild right upper abdominal pain and weakness. The patient had been treated with radical surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy for a retroperitoneal hemangiopericytoma 3 years earlier. Six months before his current physician visit, a pelvic disease recurrence with one liver metastasis occurred. The radical excision of these two tumour lesions was performed without evidence of disease in the follow-up. The findings at physical examination were normal. Laboratory studies were not significant.

The patient underwent multiphase helical CT with a bolus of 120 mL of low-osmolar iodinated contrast medium (Iomeron 400 [iomeprol], Bracco, Milan, Italy) revealing a single mass in the left lobe (Fig. 1(a)).

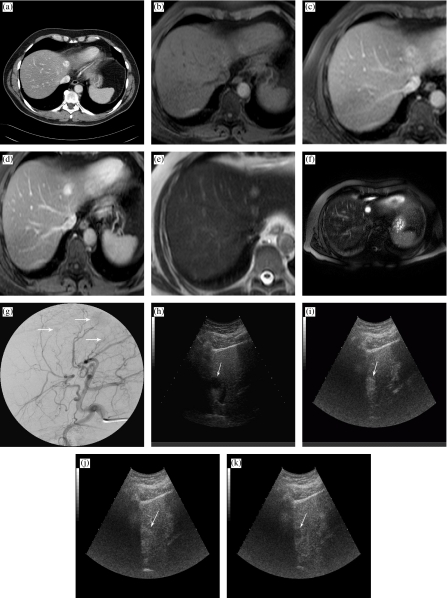

Figure 1.

A 57-year-old man with hepatic metastases of retroperitoneal hemangiopericytoma. (a) Contrast-enhanced CT reveals a mass in the left lobe. (b) T1-weighted MR image at baseline shows a mass in the left lobe. (c) Gd-BOPTA-enhanced axial T1-weighted MR image in the dynamic phase shows homogeneous enhancement of the left lobe liver lesion with multiple signal flow voids representing large tumour vessels. (d) The corresponding image of Gd-BOPTA in the delayed phase shows the wash-out of contrast agent from the metastasis with delineation. (e) T2-weighted MR image before ferumoxides. (f) Ferumoxides-enhanced axial spin-echo T2-weighted MR image reveals lesion to have homogeneously increased signal. Prominent signal voids correspond to enlarged vessels. (g) Angiography shows three tumour lesions (arrows) and demonstrates increase in the size and number of feeding arteries and a profusion of draining veins. (h) Unenhanced US scan of the liver with detection of multiple hypoechoic lesions (arrow indicates the one highlighted in this image). (i) Following BR1 administration, in the same scan of (h), the metastasis is clearly depicted and appears hyperechoic in the arterial phase (arrow). (j) In the portal venous phase, the lesion shows a central hypoechoic area with peripheral hyperechoic ring (arrow). (k) In the delayed phase, the lesion appears hypoechoic (arrow).

MRI was initially performed at baseline (Fig. 1(b)). Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI was performed using gadobenate dimeglumine (Gd-BOPTA) (MultiHance, Bracco, Milan, Italy) . All images were obtained from 1.5 Tesla MRI system (Achieva 1.5T, Philips Medical Systems, Eindhoven, Netherlands). Dynamic Gd-BOPTA-enhanced MRI revealed three well defined lesions after i.v. administration of Gd-BOPTA: one in the left lobe (Fig. 1(c)), and two in the right hepatic lobe. The three lesions were optimally visualized during delayed phase Gd-BOPTA-enhanced T1-weighted MRI (Fig. 1(d)—the left lobe lesion). MRI was also performed with ferumoxides (Endorem, Guerbet, Aulnay-sous-Bois, France) . All metastases were hyperintense on the T2-weighted MRI images obtained before and after ferumoxides administration (Fig. 1(e) and (f)—the left lobe lesion).

Hepatic angiography revealed an increase in the number and calibre of feeding arteries and draining veins in the three hepatic metastases, which were readily identified on angiograms obtained after intra-aortic injection of contrast material. Distinct tumours were apparent also during the capillary phase of the angiogram (Fig. 1(g)).

US was performed with BR1 (Sonovue, Bracco, Milan, Italy) . Unenhanced US scan of the liver showed multiple hypoechoic lesions (Fig. 1(h)). After BR1 administration, tumour lesions became markedly hyperechoic during the arterial phase (Fig. 1(i)), and appeared progressively hypoechoic with regards to the surrounding parenchyma during the portal (Fig. 1(j)) and late phase (Fig. 1(k)). US fine-needle aspiration biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of a round-cell sarcoma compatible with hemangiopericytoma.

Discussion

Among sarcomas, the most distinctive and consistent feature of hemangiopericytoma is its hypervascularity . The consensus of the literature is to treat all resectable tumour lesions, including local recurrences and a solitary metastasis, with wide excision . Imaging plays an extremely important role in the appropriate treatment planning by demonstrating the vascular nature of the tumour, revealing the exact source of its blood supply, and, finally, demonstrating its size . Increased sensitivity of new diagnostic imaging modalities in the detection and characterization of liver metastases has created a need for detailed understanding of the pathological-radiological relationship of each type of tumour. This endeavour is made difficult by the rarity of some of these tumours.

MRI and angiography are often used for evaluating hemangiopericytomas . In the reported case, angiography added further information about the number and calibre of arteries feeding and veins draining the liver metastases. US with BR1 showed detection results similar to those of Gd-BOPTA and ferumoxides-enhanced MRI and angiography. To the best of our knowledge, MRI with Gd-BOPTA and ferumoxides, and US with BR1 findings of hepatic metastases of hemangiopericytoma have not previously been reported.

Hemangiopericytomas occur most frequently in the extremities, and the retroperitoneum is the second most common site. Patients with hemangiopericytoma can experience either early or late local recurrences and distal haematogenous metastases. The most frequent sites of metastases are lung, liver and bone. The prognosis for these patients is very variable, and less than 50% are disease-free at 5 years. Recurrences can develop following an extended disease-free interval with nearly 50% of recurrences occurring at 3 or more years after diagnosis and reported cases relapsing after 20 years . Radical surgery remains the mainstay of therapy. Therefore, the early detection of locoregional and distant recurrence can play an effective role in the prognosis of these patients. A careful long-term follow-up is mandatory for these patients.

Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) is the modality of choice for follow-up imaging, in particular with regard to lung metastases, the lung being a frequent site of metastases of hemangiopericytoma . Contrast-enhanced MRI with Gd-BOPTA or ferumoxides and US with BR1 can be used for supplementary liver imaging. US with BR1 is an upcoming way to illustrate liver lesions in various vascular phases, and has some advantages over other modalities for imaging of liver metastases, such as convenience, the probability of fewer side-effects, no exposure to radiation, and no risk of missing the optimal time for observation .

References

- 1.Spitz FR, Bouvet M, Pisters PW, Pollock RE, Feig BW. Hemangiopericytoma: a 20-year single-institution experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 1998;5:350–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02303499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stout AP, Murray MR. Hemangiopericytoma: a vascular tumor featuring Zimmermann’s pericytes. Ann Surg. 1942;116:26–33. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194207000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enzinger FM, Smith BH. Hemangiopericytoma: an analysis of 106 cases. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:61–82. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(76)80006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMaster MJ, Soule EH, Ivins JC. Hemangiopericytoma: a clinicopathologic study and long-term follow-up of 60 patients. Cancer. 1975;36:2232–44. doi: 10.1002/cncr.2820360942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craven JP, Quigley TM, Bolen JW, Raker EJ. Current management and clinical outcome of hemangiopericytomas. Am J Surg. 1992;163:490–3. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(92)90394-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ravenel JG, Goodman PC. Late pulmonary metastases from hemangiopericytoma: unusual findings on CT and MR imaging. AJR. 2001;177:244–5. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.1.1770244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choyke PL, Dwyer AJ, Knopp MV. Functional tumor imaging with dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;17:509–20. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yilmaz E, Akkoclu A, Kargi A, Sevinc C, Komus N, Catalyurek H, Acikel U. Radiography, Doppler sonography, and MR angiography of malignant pulmonary hemangiopericytoma. AJR. 2003;181:1079–81. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.4.1811079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solbiati L, Tonolini M, Cova L, Nahum Goldberg S. The role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the detection of focal liver lesions. Eur Radiol. 2001;11(3):15–26. doi: 10.1007/pl00014125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersein J, Spinazzi A, Giovagnoni A, Soyer P, Terrier F, Lencioni R, et al. Focal liver lesions: evaluation of the efficacy of gadobenate dimeglumine in MR imaging: a multicenter phase III clinical study. Radiology. 2000;215:727–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.3.r00jn14727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.del Frate C, Bazzocchi M, Mortele KJ, Zuiani C, Londero V, Como G, et al. Detection of liver metastases: comparison of gadobenate dimeglumine-enhanced and ferumoxides-enhanced MR imaging examinations. Radiology. 2002;225:766–72. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2253011854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldman SM, Davidson AJ, Neal J. Retroperitoneal and pelvic hemangiopericytomas: clinical, radiological, and pathological correlation. Radiology. 1988;168:13–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.168.1.3289086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nappi O, Ritter JH, Pettinato G, Wick MR. Hemangiopericytoma: histopathological pattern or clinico-pathologic entity? Semin Diagn Pathol. 1995;12:221–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miles KA. Functional CT imaging in oncology. Eur Radiol. 2003;13(5):134–8. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-2108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]