Abstract

Previous studies have found that atmospheric brown clouds partially offset the warming effects of greenhouse gases. This finding suggests a tradeoff between the impacts of reducing emissions of aerosols and greenhouse gases. Results from a statistical model of historical rice harvests in India, coupled with regional climate scenarios from a parallel climate model, indicate that joint reductions in brown clouds and greenhouse gases would in fact have complementary, positive impacts on harvests. The results also imply that adverse climate changes due to brown clouds and greenhouse gases contributed to the slowdown in harvest growth that occurred during the past two decades.

Keywords: agricultural impact, air pollution, carbon dioxide warming, climate change, South Asia

Air pollution emissions from the burning of fossil fuels and biomass have created extensive atmospheric brown clouds (ABCs) of black carbon and other aerosols in many parts of the world (1, 2). These clouds absorb solar radiation in the lower atmosphere and scatter it back to space, thus reducing radiation at the earth's surface and partially offsetting surface warming caused by greenhouse gases (GHGs) (2–4). One of the most widespread ABCs on the planet cloaks the Indian subcontinent and the northern Indian Ocean (5). (Among the dozens of other papers on this subject, see ref. 6.) Recent research indicates that this cloud has negatively affected not only surface radiation and temperature in India but also rainfall (4, 7). ABCs reduce rainfall through a combination of mechanisms: the decrease in surface radiation reduces evaporation from the sea, the absorption of radiation in the lower atmosphere heats and stabilizes the lower atmosphere, and the higher concentration of aerosols above the Indian Ocean north of the equator than south of it weakens the latitudinal sea surface temperature gradient.

During 1930–2000, the observed cumulative increase in annual mean surface temperature in India was 0.44°C, less than in regions without ABCs, and it was smaller during the day, when the cooling effect of ABCs is strongest (4). During 1960–1998, monsoon rainfall was ≈5% lower than the 1930–1960 mean, while surface radiation decreased by ≈0.42 Wm−2 per year (4). Climate models reproduce these trends only if they include ABCs in addition to GHGs (4).

The combination of the multiple climatic effects of ABCs with the particular climatic sensitivity of the rice plant creates the possibility that reductions in ABCs and GHGs could have complementary, positive impacts on rice harvest instead of offsetting impacts. Rice harvests in India and other parts of Asia are positively correlated with rainfall (8, 9) and, late in the season, with solar radiation (10–13). On the other hand, they are negatively correlated with minimum (nighttime) temperature (10–12). Harvests might thus receive a dual boost if both the drying and dimming effects of ABCs and the warming effects of GHGs were reduced.

Only a few studies have examined the impacts of ABCs on agriculture (14, 15). They have focused on the impact of solar radiation on yield: quantity harvested divided by area harvested. They estimate that the dimming effect of ABCs has reduced rice yield by 6–17%. They have been criticized, however, for using process-based crop-response simulation models, which might not accurately reflect crop growth under actual field conditions (13). A particular problem is an assumption that farmers apply agricultural inputs at agronomically optimal levels, which artificially makes radiation the limiting factor on yield and thus exaggerates the predicted impact of dimming. On the other hand, by focusing on yield, the studies have ignored the potential impacts of climate changes on area harvested (9), which could cause them to understate the full impact of ABCs on harvest. No previous study has examined the multiple impacts of ABCs on agriculture or their interaction with the impacts of GHGs, in India or any other country.

In view of the criticisms of studies based on crop-response simulation models, we used multivariate regression methods and historical data from nine major rice-growing states of India to construct a statistical agro-economic model of rice harvest, which we then coupled to a parallel climate model (PCM) to simulate the historical impacts of ABCs and GHGs. The agro-economic model consisted of two interrelated equations, a production function and an area demand function. We predicted the impacts of reductions in ABCs and GHGs on historical rice production by running three alternative climate scenarios through the agroeconomic model. We focused on harvest during the wet season (kharif), which accounts for ≈90% of total annual harvest.

Results

Regression Coefficients in the Agro-Economic Model.

Table 1 shows the estimated regression coefficients on the climate variables in the two equations of the agro-economic model. See supporting information (SI) for full regression results, including coefficient estimates on the nonclimate variables. We found that just two climate variables were statistically significant (P < 0.05) in either equation: June–September rainfall (both equations) and October–November minimum temperature (production function only). The signs of the coefficients were as expected: positive on rainfall (harvest is larger if there is more rain) and negative on minimum temperature (harvest is smaller if minimum temperature is higher). Given that ABCs have both drying and cooling effects, the opposing signs indicate that the net impact of ABCs on rice harvest is ambiguous. Because of the logarithmic specification of the model, the coefficients are interpretable as elasticities: a 1% increase in climate variable j affects quantity harvested or area harvested by γ̂j%, where γ̂j is the coefficient on the variable. The absolute values of the coefficients on June–September rainfall and October–November minimum temperature are less than one, so these variables had less-than-proportionate impacts on harvest.

Table 1.

Regression coefficients on climate variables in agro-economic model

| Variable | Production function | Area demand function |

|---|---|---|

| Rainfall: March–May | −0.027 | 0.011* |

| Rainfall: June–September | 0.317*** | 0.074*** |

| Rainfall: October–November | 0.013 | −0.000 |

| Minimum temperature: June–September | 0.662 | 0.135 |

| Minimum temperature: October–November | −0.865** | −0.059 |

| Solar radiation: October–November | −0.048 | 0.005 |

| Solar radiation: December | −0.085 | 0.151 |

Production function shows the natural logarithm of quantity of rice harvested in thousand metric tons; area demand function shows the natural logarithm of area harvested in thousand hectares. Climate variables are also in natural logarithms. P values (two-tailed t tests):

***, P < 0.01;

**, P < 0.05,

*, P < 0.1. Coefficients significantly different from zero at P < 0.05 are in bold. See SI for results for nonclimate variables.

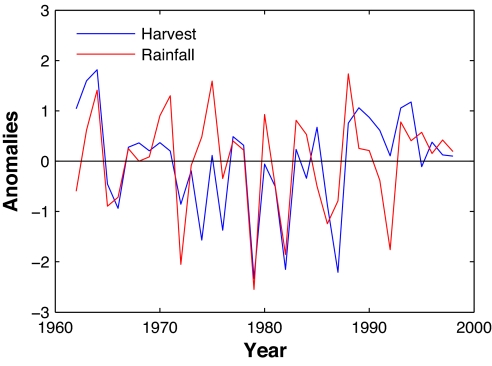

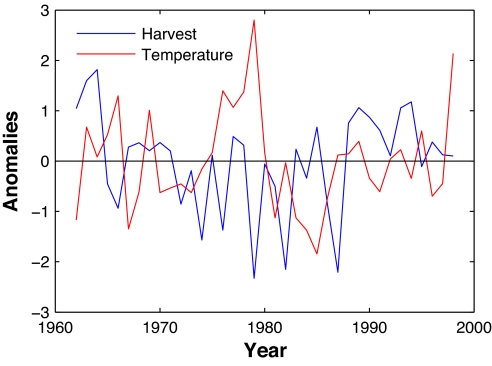

The positive impact of June–September rainfall on harvest and, to a lesser extent, the negative impact of October–November minimum temperature are evident even in the aggregate, raw data. Fig. 1 shows the annual anomalies in harvests and June–September rainfall. We constructed the harvest anomalies by aggregating wet-season harvests across the nine states and then detrending and normalizing the resulting aggregate variable, so that it had a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. For June–September rainfall, we constructed the aggregate variable by weighting rainfall in each state by the state's share of aggregate rice harvest, and then we detrended and normalized that variable. As can be seen in Fig. 1, the peaks and troughs of the two series largely coincide. The Pearson correlation coefficient for the two series is +0.61 (P < 0.01). Fig. 2 shows the anomalies in harvests and October–November minimum temperature, constructed using the same procedures. The peaks in one series now tend to coincide with troughs in the other, and the Pearson correlation coefficient is −0.26 (P = 0.12). October–November minimum temperature has a statistically significant (P < 0.05) impact on harvest only if we control for June–September rainfall and other explanatory variables, as in the regression results in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Anomalies in June–September rainfall (red) and wet-season rice harvest (blue) in India. Data were aggregated across the nine predominantly rain-fed rice-growing states in the country and then detrended and normalized. Anomalies are expressed in terms of numbers of standard deviations. The pattern indicates a strong positive correlation between the two series.

Fig. 2.

Anomalies in October–November minimum temperature (red) and wet-season rice harvest (blue) in India. See Fig. 1 for explanation. In contrast to Fig. 1, the pattern here suggests a weak negative correlation between the series.

In view of these results, we included only the coefficients on June–September rainfall and October–November minimum temperature from the production function, and June–September rainfall from the area demand function, when we predicted the impacts of hypothetical reductions in ABCs and GHGs on historical rice production. We note that the insignificance of the solar radiation variables could be a statistical artifact. The December radiation variable became significant in the area demand function, and nearly so in the production function, if we excluded yearly fixed effects from the regressions (see SI). The variable's insignificance when we included the yearly fixed effects might thus be due to its limited variation over time, not to the lack of an actual impact on harvest. If so, then our predictions understate the agricultural benefits of reducing ABCs.

Impacts of ABCs and GHGs on Historical Rice Harvests.

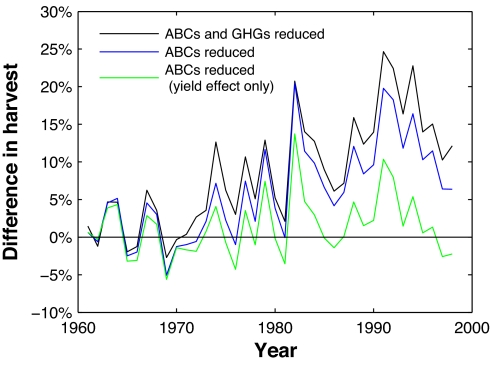

Fig. 3 shows the year-by-year percentage impacts of hypothetical reductions of ABCs and GHGs on historical rice harvests. When only ABCs are reduced and only the yield effect is included, the differences are mostly positive during the latter part of the period. This result indicates that historical rice harvests would have been larger in the absence of ABCs. Although the coefficient on October–November minimum temperature in the production function exceeds the coefficient on June–September rainfall (Table 1), the parallel climate model (PCM) predicts that the elimination of ABCs would increase rainfall much more than minimum temperature (see SI), and so the net impact on yield tends to be positive.

Fig. 3.

Predicted impact of reductions in ABCs and GHGs on wet-season rice harvest in a representative rainfed rice-growing region in India. Three hypothetical changes are shown: both ABCs and GHGs reduced, with impacts on both yield and area harvested (black); only ABCs reduced, with impacts on both yield and area harvested (blue); and only ABCs reduced, with impact on only yield (green).

The differences are much larger when only ABCs are reduced but the area effect is added to the yield effect. This finding indicates that ABCs affected historical rice output mainly through the effect of rainfall on area: in the absence of ABCs, wetter conditions would have led to an expansion of rice area. Although the coefficient on June–September rainfall in the area demand function is small (Table 1), the area effect accumulates because the area demand function includes lagged area harvested, and this causes the predicted increase in harvest to rise over time.

The differences are greatest when ABCs and GHGs are simultaneously reduced and both the yield and area effects are included. This finding indicates that historical rice harvest would have been even larger if the reduction of ABCs had been accompanied by a reduction in GHGs. The extra boost to the harvest is due to the reduction in October–November minimum temperature.

Table 2 compares the mean impacts during the first and second parts of the period. It starts with 1966, which marks the beginning of the era of modern rice cultivation in India, the “Green Revolution.” Mean impacts differed significantly between the two parts only when the area effect was included. The simultaneous reduction of ABCs and GHGs would have increased mean annual rice harvest by 6.18% during 1966–1984 and 14.4% during 1985–1998, with the difference being highly significant (P < 0.01).

Table 2.

Mean predicted increases in wet-season rice harvest in response to reductions in ABCs and GHGs

| Hypothetical change | Time period | Means, % | H0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Both ABCs and GHGs reduced, with impacts on both yield and area | 1966–1984 | 6.18 | Reject (P < 0.01) |

| 1985–1998 | 14.4 | ||

| Only ABCs reduced, with impacts on both yield and area | 1966–1984 | 3.94 | Reject (P < 0.01) |

| 1985–1998 | 10.6 | ||

| Only ABCs reduced, with impact on only yield | 1966–1984 | 0.97 | Fail to reject (P = 0.45) |

| 1985–1998 | 2.09 |

Predictions refer to a representative rainfed rice-growing region in India and are drawn from Fig. 3. Means tests were conducted using two-tailed t tests with unequal variances for the two time periods. For H0, means are equal for the two periods.

Discussion

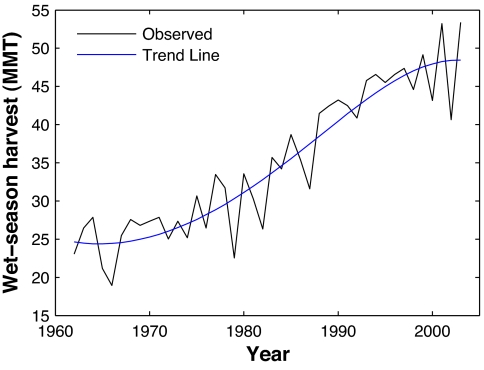

The evidence of a greater impact by ABCs and GHGs during the more recent period is interesting in view of historical trends in Indian rice harvests (Fig. 4). Thanks to the Green Revolution, rice harvests grew dramatically after the mid-1960s. They have grown more slowly since the 1980s; however, the annual growth rate peaked at nearly 3% in 1984–1985 and leveled off by the early 2000s. This deceleration has raised concerns that food shortages could recur (16, 17). Many explanations for the deceleration have been offered, including falling rice prices, deteriorating irrigation infrastructure, soil degradation, stagnant technology on rain-fed farms, and the technological frontier being reached on irrigated farms (16). Our explanation, adverse regional climate change caused by the combined effects of ABCs and GHGs, augments these explanations. Previous statistical studies on the climate sensitivity of Indian agriculture did not detect it for two reasons: they ignored ABCs, and their sample periods ended in the 1980s, before the deceleration occurred (18, 19).

Fig. 4.

Historical trend in wet-season rice harvest in India. MMT, million metric tons. Observed values (black) are summed across the nine predominantly rain-fed rice-growing states in the country. The trend line (blue), a cubic polynomial relating ln(harvest) to year, was fitted using ordinary least squares regression. The annual growth rate along the trend line peaked at 2.70% in 1984–1985.

Our estimates of the impact of just ABCs on rice harvest, 3.94% during 1966–84 and 10.6% during 1985–1998 (Table 2), are within the range of the previous estimates cited earlier. They differ, however, in several important ways: they are derived from a statistical model based on historical data instead of a crop-response simulation model, they account for both area and yield effects instead of just the latter, and they reflect the impacts of drying and cooling instead of dimming. As already mentioned, the omission of the impact of dimming perhaps causes our estimates to understate the amount by which rice harvest would have increased if ABCs had been reduced. Our estimates are conservative for two additional reasons: they ignore the possibility that farmers might have achieved even greater rice harvests by adjusting other inputs besides area harvested (20), and they ignore direct damage to rice caused by air pollution (21). Some direct damage from aerosols might be reflected in the June–September rainfall variable: heavy rains reduce the concentrations of aerosols to which rice plants are exposed, and this could contribute to the positive impact of the rainfall variable in the regression equations. Because the estimates in Table 2 ignore the fact that any incremental rice area would have displaced other crops, they should not be taken as indications of the net impact of ABCs on the overall Indian agricultural sector.

The combustion processes that generate aerosols also generate GHGs. Our finding that simultaneous reductions in ABCs and GHGs would provide benefits to rice farmers is thus reassuring. For rice farming at least, we do not find evidence of a tradeoff between the impacts of reducing ABCs and GHGs. Reductions in ABCs would increase surface warming, but the impact would be mainly on daytime temperatures, not on the night-time temperatures that negatively effect rice, and it would in any event be outweighed by a beneficial increase in rainfall. To reduce night-time temperatures, reductions in GHGs are needed. We cannot say, of course, whether this complementarity of impacts would also occur for other crops in other countries. Understanding of the regional climate impacts of ABCs remains limited, and the climate sensitivity of crops varies, but at least we can say that a tradeoff is not inevitable.

Methods

Agro-Economic Model.

To construct the model, we compiled time-series data on agricultural and meteorological variables for nine Indian states that receive monsoon rainfall during June–September and have predominantly rain-fed farms: Assam, Bihar, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Orissa, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal. These states account for about two-thirds of India's wet-season harvest.

The production function related annual rice harvest in each state to area harvested, other agricultural inputs (labor, fertilizer, high-yielding seeds, irrigation), and climate (rainfall, radiation, temperature). Consideration of crop calendars and previous studies (8–13) led us to test the significance of the seven climate variables listed in Table 1. To analyze the impacts of climate on area harvested, we also estimated an area demand function. This function related area harvested in the current year to area harvested during the previous year, prices of agricultural outputs and inputs, and the same climate variables as in the production function. We estimated the area demand function first, and used fitted values from it in place of the observed values of the area harvested variable when we estimated the production function. This two-stage procedure avoids statistical biases that could result from the simultaneous determination of quantity harvested and area harvested (22).

We allowed the intercepts in both equations to vary across both states and years, to control for unobserved fixed factors that could cause mean harvest to differ along those dimensions. The yearly fixed effects implicitly detrend the variables, with year-to-year changes not constrained to be equal, as would be the case if we included simple time trends. In line with previous studies (22), we expressed all variables in logarithmic form. The sample period for estimating both equations was 1972–1998, determined by data availability. Additional details on the statistical model are presented in SI.

Climate Scenarios.

We used output from the PCM developed by the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research to define the climate scenarios (23, 24). The output had been generated for the study by Ramanathan et al. (4). We focused on 1961–1998, which is the period when there is evidence of climate impacts due to ABCs (4). In view of the greater reliability of the PCM at larger scales, we averaged the output across grid cells corresponding to the nine states. Our predictions thus refer to the entire rain-fed region of India, not individual states.

We defined three scenarios. In scenario 1, we set the values of climate variables equal to PCM output from ABC_1998: Run 1, which includes the climate effects of both ABCs and GHGs (and sulfates). This run best reproduces observed climate trends in India. In scenario 2, we set the variables equal to the average of PCM output across the eight ensemble GHGs+SO4_1998 runs, which include the climate impacts of GHGs (and sulfates) but not ABCs. Scenario 3 was the same as scenario 2 except we replaced the PCM output for minimum temperature with the mean of observed minimum temperature during 1930–1960. The difference in rice harvest between scenarios 1 and 2 provides a prediction of the historical impact of reducing only ABCs, whereas the difference between scenarios 1 and 3 predicts the impact of simultaneously reducing ABCs and GHGs.

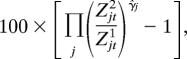

Given the two-equation structure of the agro-economic model, we were able to decompose the impact into a yield effect and an area effect. The yield effect refers to the change in harvest when area harvested is held at its historical level, whereas the area effect refers to the change in area harvested that occurs in response to differences in climate variables between the scenarios. We expressed both effects as percentage differences in rice harvests between the scenarios. The yield effect for the comparison of scenarios 1 and 2 was given by

|

where Zjt1 and Zjt2 are the values of climate variable j in year t under scenarios 1 and 2, respectively, and γ̂j is the corresponding coefficient from the production function. We derived this expression from the production function, setting all variables besides the climate variables equal to their observed historical levels. The expression for the area effect was broadly similar but involved lagged terms and coefficients from both the production and area demand functions. The expressions for the comparison of scenarios 1 and 3 were the same as those for the comparison of scenarios 1 and 2 except that variables for scenario 3 were used in place of variables for scenario 2.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Bee, R. Carson, and D. Dawe for helpful discussions; E. Chung, F. Li, and D. Kim for data assistance; and P. S. Dasgupta, J. Meehl, C. P. Timmer, and T. N. Krishnamurty for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the Giannini Foundation, National Science Foundation Grant ATM 0201946, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Grant NA17RJ1231, and the University of California Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation.

Abbreviations

- ABC

atmospheric brown cloud

- GHG

greenhouse gas

- PCM

parallel climate model.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See Commentary on page 19609.

This article contains supporting information (SI) online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0609584104/DC1.

References

- 1.Kaufman YJ, Tanré D, Boucher O. Nature. 2002;419:215–223. doi: 10.1038/nature01091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramanathan V, Crutzen PJ, Kiehl JT, Rosenfeld D. Science. 2001;294:2119–2124. doi: 10.1126/science.1064034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wild M, Gilgen H, Roesch A, Ohmura A, Long CN, Dutton EG, Forgan B, Kallis A, Russak V, Tsvetkov A. Science. 2005;308:847–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1103215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramanathan V, Chung C, Kim D, Bettge T, Buja L, Kiehl JT, Washington WM, Fu Q, Sikka DR, Wild M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5326–5333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500656102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramanathan V, Crutzen PJ, Lelieveld J, Mitra AP, Althausen D, Anderson J, Andreae MO, Cantrell W, Cass GR, Chung CE, et al. J Geophys Res. 2001;106:28371–28398. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leon J-F, Chazette P, Dulac F, Pelon J, Flamant C, Bonazzola M, Foret G, Alfaro SC, Cachier H, Cautenet S, et al. J Geophys Res. 2001;106:28427–28440. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung CE, Ramanathan V. J Climate. 2006;19:2036–2045. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webster PJ, Magana VO, Palmer TN, Shukla J, Thomas RA, Yanai M, Yasunari T. J Geophys Res. 1998;103:14451–14510. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar KK, Kumar KR, Ashrit RG, Deshpande NR, Hansen JW. Int J Climatol. 2004;24:1375–1393. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hossain M. In: Applications of Systems Approaches at the Farm and Regional Levels. Teng PS, Kropff MJ, ten Berge HFM, Dent JB, Lansigan FP, van Laar HH, editors. Vol 1. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 1997. pp. 263–279. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pathak H, Ladha JK, Aggarwal PK, Peng S, Das S, Singh Y, Singh B, Kamra SK, Mishra B, Sastri ASRAS, et al. Field Crops Res. 2003;80:223–234. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng S, Huang J, Sheehy JE, Laza RC, Visperas RM, Zhong X, Centeno GS, Khush GS, Cassman KG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9971–9975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403720101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanhill G, Cohen S. Agric Forest Meteorol. 2001;107:255–278. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chameides WL, Yu H, Liu SC, Bergin M, Zhou X, Mearns L, Wang G, Kiang CS, Saylor RD, Luo C, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13626–13633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United Nations Environment Programme and Center for Clouds, Chemistry and Climate. The Asian Brown Cloud: Climate and Other Environmental Impacts. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pingali PL, Hossain M, Gerpacio RV. Asian Rice Bowls: The Returning Crisis? Wallingford, UK: CAB International; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barker R, Dawe D. In: Developments in the Asian Rice Economy. Sombilla M, Hossain M, Hardy B, editors. Manila, The Philippines: International Rice Research Institute; 2002. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dinar A, Mendelsohn R, Evenson R, Parikh J, Sanghi A, Kumar K, McKinsey J, Lonergan S. Measuring the Impact of Climate Change on Indian Agriculture. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 1998. Technical Paper 402. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendelsohn R, Dinar A, Basist A, Kurukulasuriya P, Ajwad MI, Kogan F, Williams C. Cross-Sectional Analyses of Climate Change Impacts. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2004. Policy Research Working Paper 3350. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McConnell KE, Bockstael NE. Mäler K-G, Vincent JR. Handbook of Environmental Economics. Vol 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 621–669. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chameides WL, Kasibhatla PS, Yienger J, Levy H., Jr Science. 1994;264:74–77. doi: 10.1126/science.264.5155.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mundlak Y. In: Handbook of Agricultural Economics. Gardner B, Rausser G, editors. Vol 1. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2001. pp. 3–85. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Washington WM, Weatherly JW, Meehl GA, Semtner AJ, Jr, Bettge TW, Craig AP, Strand WG, Jr, Arblaster JM, Wayland VB, James R, et al. Climate Dyn. 2000;16:755–774. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai A, Wigley TML, Boville BA, Kiehl JT, Buja LE. J Climate. 2001;14:485–519. [Google Scholar]