Abstract

This article provides an introduction to the special issue on intervention development and cultural adaptation research with diverse families. The need for research on intervention development and on cultural adaptation of interventions is presented, followed by a discussion of frameworks on treatment development. Seven articles included in this special issue serve as examples of the stages of treatment and intervention development, and of the procedures employed in the cultural adaptation with diverse families. An overview of the seven articles is provided to illustrate the treatment development process and the use of pluralistic research methods. We conclude with a call to the field for creative and innovative intervention development research with diverse families to contribute to the body of evidence-based practice with these populations.

Keywords: Treatment, Intervention, Research, Culture, Families, Diversity

Developing new family treatments and adapting interventions to the particular needs of families is a challenge for the field. Family therapy was probably one of the first interventions “developed” by creative and innovative clinicians struggling with the limits of individual psychotherapy in the changing context of a post-World War II society. In fact, family therapy was perhaps one of the first major cultural adaptations made of individual and group psychotherapy, in part as a response to the changing social and cultural context in industrialized societies. Indeed, the consideration of context is the hallmark of the family systems approach; therefore, by logic, culture should be a key aspect of all family approaches. Relatively early in the family therapy movement, proposals were made for the consideration of culture (Kluckhohn, 1958; Kluckhohn & Strodbeck, 1961; Spiegel, 1971). Yet, it was not until 1982, with the publication of the now seminal work on ethnicity and family therapy, that models with specific recommendations and guidelines for the inclusion of ethnicity and cultural processes in clinical practice were proposed (McGoldrick, Pearce, & Giordano, 1982). The thesis advanced in this approach is that therapy is more effective when it is congruent with the culture and context of the patient or client population.

During the last two decades, a rich clinical literature on ethnicity and culture has evolved that serves to inform clinical practice in family therapy (Boyd-Franklin, 1989; Chao & Kaslow, 2002; Comas-Díaz & Griffith, 1988; Falicov, 1983, 1998; Imber-Black, 1988; Jalali, 1988; Lee, 1996; McDaniel, Lusterman, & Philpot, 2001; McGoldrick, Giordano, & Pearce, 1996; Montalvo, Gutierrez, & Falicov, 1988). Another literature on ethnicity and minorities also called attention to the problems of treating ethnic and language minorities with conventional psychological approaches, suggesting the need to adapt treatments (Aponte, Younng Rivers, & Wohl, 1995; Bernal, Bonilla, & Bellido, 1995; Bernal & Sáez-Santiago, 2005, 2006; Betancourt & López, 1993; Casas, 1995; Comas-Díaz & Griffith, 1988; Domenech-Rodríguez & Wieling, 2004; López et al., 1989; Mays & Albee, 1992; Nagayama Hall, 2001; Pendersen, 2003; Ponterotto, Casas, Suzuki, & Alexander, 1995; Sue & Zane, 1987). Recently, practice guidelines have been published for working with multicultural (American Psychological Association, 2002) and ethnic minority populations (Council of National Psychological Associations for the Advancement of Ethnic Minority Interests, 2003), and a new literature has emerged around the issue of multiculturalism and cultural competence (Sue, Arendondo, & McDavis, 1992; Sue & Torino, 2005). However, too few studies have incorporated culture and ethnicity as part of the intervention or even tested the effectiveness of these interventions.

Treatment and intervention research lags behind in developing, adapting, and testing novel approaches with diverse populations (Bernal & Scharrón-del-Río, 2001; Mays & Albee, 1992), and clinical trials are certainly not characterized by the diversity in their samples (Miranda, Nakamura, & Bernal, 2003). A challenge for our field is the articulation and documentation of how ethnicity and culture play a role in the treatment process and how interventions may need to be adapted or tailored to meet the needs of diverse families. With this special issue, we hope to help bridge the gap between clinical practice and research. We focus on both cultural adaptations of treatments and intervention development research.

TREATMENT AND INTERVENTION DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH

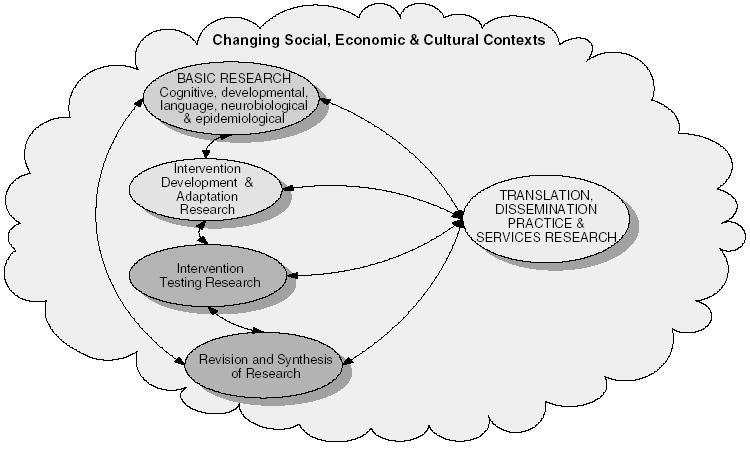

Treatment and intervention development is an essential element in the scientific process. In a report by the National Institute of Mental Health, “Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment” (National Advisory Mental Health Council, 2001), a conceptual framework for effective deployment and translation of science into practice was proposed. Figure 1 is a modification (in italics) of the framework that includes (1) basic research (neurobiological, cognitive, developmental, and epidemiologic research); (2) intervention development, refinement, and adaptation; (3) testing of the efficacy of interventions; (4) deployment, dissemination, and practice research; (5) review and integration of findings to identify effective interventions; and (6) the evolving social, economic, and cultural context.

Figure 1.

A Model for Effective Deployment and Translation of Science Into Practice

This conceptual framework provides an overview of the complex process involved in the development, testing, and dissemination of treatments. Findings in these five areas of research, or “processes” in research, are recursive and serve to inform the basis for conceptualizing, developing, and testing the intervention. At the top of Figure 1, basic research and theory in fields such as learning, cognition, development, and neuroscience informs treatment development. Once an intervention has been developed, refined, adapted, and evaluated, it is ready for more rigorous research on intervention testing. Efficacy tests are well-controlled trials with families. Intervention testing may also entail studies of mediator and moderator variables in relation to outcome. Analyses of mediators examine the theoretical change mechanisms by which the intervention purportedly has its effects. Analysis of moderators evaluates which patient characteristics are best suited by the intervention. Another aspect of the framework is the systematic review of research, in which methods such as meta-analysis are employed to identify a corpus of information on status of evidence-based treatments. The fifth aspect of the framework entails the deployment of interventions. This includes technology transfer and translation of evidence-based interventions to the field in such a way that the degree to which these interventions can be adopted, applied, and remain effective in front-line health settings can be assessed. Large effectiveness trials are often aimed at moving interventions from the highly controlled environments to actual clinical settings (e.g., effectiveness studies in front-line clinical settings, large multisite trials, translations and transportation of treatments to health settings, and cost-effectiveness studies; National Advisory Mental Health Council, 2001).

Additionally, the interconnectivity between the elements of the model is depicted with bidirectional arrows to reflect reciprocal influence among the elements. For example, basic research may both influence and be influenced by intervention development research. The reciprocal interconnections among the elements of the framework are a reflection of the nonlinear relationship between science and practice (National Advisory Mental Health Council, 2001). Finally, these elements of the research enterprise aimed at developing, evaluating, and testing interventions are not only interconnected but are also embedded in ever-changing social, cultural, and economic contexts of mental health care. The changing context is depicted by the cloud in which the elements of the framework are embedded.

Intervention development draws from the model established by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval process for pharmacological treatments. The four-phase medical model for pharmacological therapies includes phase 1 (evaluation of side effects, dosing, and early evidence of effectiveness), phase 2 (open and controlled clinical trials that evaluate short-term side effects, risks, and tolerability), phase 3 (randomized controlled trials after preliminary evidence suggests effectiveness and evaluates benefit-risk relationship), and phase 4 (postmarketing studies, evaluation of effectiveness, safety, and cost-benefit, and optimal use in clinical practice; National Library of Medicine, 2006).

A psychological stage model of behavioral therapies was originally proposed by Onken, Blaine, and Battjes (1997) and later revised by Rounsaville, Carroll, and Onken (2001) as an alternative to the FDA approach. This stage model of research was developed because of the increased complexity and methodological advances in conducting clinical trials of psychosocial treatments. This stage model of behavioral therapies establishes three basic categories in the research process: clinical innovation (creative observation and documentation), efficacy (internal validity), and effectiveness (external validity). The treatment development approach requires expositing a theory of change; developing a theory-based intervention; writing protocols or a manual for the intervention; training for the intervention providers; carrying out pilot, efficacy, and effectiveness studies; and translating. Thus, a first stage (1a) includes an exposition of the change mechanisms by which the new treatment is purported to operate, development of protocols or a treatment manual, and exploratory work with a small number of patients (n = +/− 10). A second part of this stage (1b) entails the training of intervention providers or therapists in delivering the intervention and carrying out a small randomized pilot study (n = +/− 40). The main goal of the pilot study is to provide a test of efficacy prior to a full-scale clinical trial. With positive outcomes at stage 1, the investigator then proceeds to testing the intervention, by means of a randomized clinical trial (stage 2), to either control or treatment-as-usual conditions. This stage also includes analyses of the mediators and moderators associated to outcomes. Stage 3 studies move the intervention from highly controlled clinical environments, such as university settings, to community and hospital-based settings to test effectiveness.

Both the model for effective deployment and translation of science into practice (National Advisory Mental Health Council, 2001) and the stage model of behavioral therapies research (Rounsaville et al., 2001) complement each other and serve as frameworks within which to view the intervention and treatment development process as part of a larger research agenda. All the articles for this special issue discuss treatment or intervention development, refinement, and adaptation research, as shown in the second oval in Figure 1. Similarly, all the articles exemplify key elements of stage 1a or 1b of the three-stage model in preparation for a rigorous testing of the intervention.

INTRODUCTION TO THE SPECIAL ISSUE

The special issue aims to (1) highlight different approaches to intervention development research and adaptation of treatments for work with families of diverse populations; (2) present illustrative studies of empirical research in intervention and treatment development that use novel qualitative and quantitative approaches; and (3) provide examples of successful innovative approaches in the different phases of adaptation and intervention development that relate to culturally responsive approaches to diverse populations.

The changing demographics in the United States point to an increasingly ethnically and racially diverse population. By the year 2050, it is expected that racial and ethnic minority groups will constitute half of the total U.S. population (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2001). However, few treatments and interventions have been tested with culturally diverse groups. The articles focus on both the adaptation and development of empirically grounded interventions with diverse families such as African Americans, Latinos, inner-city homeless, and White families. Although these seven articles are not representative of the rich multicultural diversity of our times, they serve as examples of early treatment development efforts with different settings, disorders, ethnicities, cultural processes, and methodological approaches. The articles are presented according to the particular stage of treatment development being addressed. Thus, we begin with more conceptual and theoretical articles (Breland-Noble, Bell, & Nicolas, 2006; Weisman, Duarte, Koneru, & Wasserman, 2006) and move to stage 1a studies on feasibility and manual development (Boyd, Diamond, & Bourjolly, 2006; Matos, Torres, Santiago, Jurado, & Rodríguez, 2006), and then to an example of a stage 1b study that evaluates feasibility, acceptability, and a preliminary test of effectiveness (Uebelacker, Hecht, & Miller, 2006). Next is an article that describes the various steps in treatment development process (Fraenkel, 2006) and a seventh article that reviews an established program of treatment research currently focused on dissemination and transportability (Santisteban, Suarez-Morales, Robins, & Szapocznik, 2006).

Breland-Noble, Bell, and Nicolas (2006) present their work on developing an evidence-based intervention that targets the use of psychiatric clinical care by African American families. Cultural concepts are identified—such as John Henryism, the faith community, and stigma—on which to build an intervention to reduce barriers to clinical care. The authors present the conceptual basis of their model, consider the change mechanism for engagement, and propose a motivational interviewing intervention to improve familial engagement into mental health care. This is an early stage 1a (Rounsaville et al., 2001) treatment development study in preparation for a pilot study to create a manual and test feasibility.

A second article by Weisman et al. (2006) discusses the development of a culturally informed family treatment for schizophrenia that was developed in English and Spanish in South Florida and intended to target Hispanic families. This 15-session treatment is grounded in literature on expressed emotion, attribution theory, spirituality, and family cohesion. The early work on the development of the culturally informed therapy for schizophrenia (CIT-S) is presented. The CIT-S incorporates modules on family spiritual coping, communication, and training and problem solving, and is currently undergoing pilot testing. Weisman and colleagues discuss the complexities of including a diversity of ethnic, cultural, and language groups into the protocol, which is a challenge to the field.

A preventive intervention for depressed, low-income, and ethnically diverse urban families is the focus of a third article (Boyd et al., 2006). Here, an intervention for children of parents with depression is the focus of intervention development work. Focus groups were conducted at community mental health centers with parents and mental health providers. The themes from the focus groups with parents (social support, depression and its symptoms, parenting concerns, helpful activities, life stress, child and family issues, intervention design) and mental health professionals (parenting difficulties, social support, community issues, mental health practices, and intervention design) served to inform the development of the manual. This article serves to illustrate an approach to manual development using the qualitative data from focus groups.

The article by Matos and colleagues (2006) examines how parent-child interaction therapy (PCIT) was adapted for Puerto Rican parents of preschool children with hyperactivity and other behavior problems. The authors begin with an established intervention and view it through the cultural lens. This process is based on a conceptual framework for adaptation, and the authors employed both quantitative and qualitative methods in their approach. The four steps described are (1) translation and preliminary cultural adaptation of PCIT; (2) the application of PCIT to 9 families; (3) treatment revision and refinement; and (4) in-depth interviews with parents and professionals. This exploratory pilot study served as a basis on which to adapt manuals, make the appropriate changes in the treatment protocol, and test procedures in preparation for a preliminary trial of efficacy. This is another illustration of a stage 1a treatment development and adaptation study.

The article by Uebelacker et al. (2006) is an open clinical trial of a two-session family intervention that consists of assessment, feedback, discussion, and goal setting. The Family Check-Up is based on the McMaster model of family functioning and uses motivational interviewing strategies to help families identify problems and increase motivation. The sample was predominantly White, and 73% have at least a high school education. This stage 1b treatment development study demonstrates that the intervention is both feasible and acceptable to families. The positive outcomes on functioning suggest that a randomized clinical trial is a logical next step.

The collaborative family program development (CFPD) model is presented by Fraenkel (2006) for working with homeless families in New York City. CFPD is conceptually based on systems thinking and is firmly rooted in a collaborative community approach in which professionals assume a position of learning from families, and families are invited as coinvestigators with the professional researchers. The story of the CFPD intervention is told in 10 steps: the initiation of the project and forming collaborative professional relationships, engaging cultural consultants, intensive interviews of family members, professionals in the community, qualitative codes, designing the program in terms of content and drafting a manual, pilot testing, manual revision, evaluation of effectiveness, and dissemination and adaptation of the program to other settings. This article illustrates in 10 steps the intervention development, refinement, testing, and dissemination process of the models of treatment development presented above.

The seventh article, by Santisteban, Suarez-Morales, Robbins, and Szapocznik (2006), presents a review of a 30-year program of research on brief strategic family therapy (BSFT). This program of family therapy research began with early treatment development and adaptation of BSFT to the stressors faced by Hispanic families and the consideration of key aspects of the Latino culture in the treatment process itself. It illustrates nearly all the stages of treatment development with BSFT that span theory construction, early development of the treatment in terms of feasibility and acceptability, consideration of cultural values as part of the treatment, modifications of the protocol to attend to issues of engagement into treatment, and randomized clinical trials that document the empirical support for this model. The ongoing efforts of this impressive program of research are centered on the transportability and dissemination of BSFT through the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s Clinical Trials Network.

As a whole, these seven articles exemplify the range of treatment development and cultural adaptation research with diverse populations at different points in the research development process. Theory building and construction is critical because a basic question is not only if a treatment works but also how it works. So, constructing a study that can eventually examine causal processes is central. All the articles developed or adapted treatments to meet the specific needs of their patient population, and all made modifications in the protocol to ensure the ecological validity of the interventions (Bernal et al., 1995). The articles illustrate how treatment development begins with qualitative work either through case studies, careful documentation of processes, or interviewing of participants. Several of the articles used both qualitative and quantitative approaches in the effort to develop or adapt manuals and conduct a preliminary evaluation of the treatment or intervention.

Indeed, because treatment and intervention development research is by its very nature preliminary and “developmental,” the methods used are often exploratory, qualitative, or a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches. Generally, the results are not clear cut in terms of the outcomes beyond setting the stage for a more rigorous test of the intervention. Thus, investigators often face barriers to publishing their work because journals generally apply the criteria of randomized clinical trials to studies that evaluate outcomes. In fact, few venues exist for innovative intervention and treatment research; this is particularly the case of developmental research on family interventions. With this special issue, we take a firm position that Family Process is a venue for creative and innovative developmental family intervention treatment research. We expect that the articles presented here serve to stimulate other colleagues in the field to publish their exploratory work on intervention development and adaptations, and as such, contribute to the growing body of research on evidenced-based family interventions for diverse and multicultural populations.

Footnotes

Support for this manuscript was provided in part by the National Institute on Mental Health, Division of Services and Intervention Research, Psychosocial Treatment Research Program–Child & Adolescent Treatment & Preventive Intervention Branch, Grant No. 1 R01 MH67893.

References

- American Psychological Association. Guidelines on multicultural education, training, research, practice, and organizational change for psychologists. American Psychologist. 2002;58:377–402. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.5.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aponte JF, Younng Rivers R, Wohl J. Psychological interventions and cultural diversity. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Bonilla J, Bellido C. Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: Issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1995;23:67–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01447045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Sáez-Santiago E. Toward culturally centered and evidenced based treatments for depressed adolescents. In: Pinsof WM, Lebow J, editors. Family psychology: The art of the science. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 471–489. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Sáez-Santiago E. Culturally centered psychosocial interventions. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34:121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Scharrón-del-Río MR. Are empirically supported treatments valid for ethnic minorities? Toward an alternative approach for treatment research. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2001;7:328–342. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt H, López SR. The study of culture, ethnicity, and race in American psychology. American Psychologist. 1993;48:629–637. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd RC, Diamond GS, Bourjolly JN. Developing a family-based depression prevention program in urban community mental health clinics: A qualitative investigation. Family Process. 2006;45:187–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Franklin N. Black families in therapy: A multisystems approach. New York: Guilford Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Breland-Noble AM, Bell C, Nicolas G. Family first: The development of an evidence-based family intervention for increasing participation in psychiatric clinical care and research in depressed African American adolescents. Family Process. 2006;45:153–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas M. Counseling and psychotherapy with racial/ethnic minority groups in theory and practice. In: Bongar V, Buetler LE, editors. Comprehensive textbook of psychotherapy: Theory and practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 311–335. [Google Scholar]

- Chao CM, Kaslow FW. Comprehensive handbook of psychotherapy: Interpersonal/humanistic/existential. Vol. 3. New York: Wiley; 2002. The central role of culture: Working with Asian children and families; pp. 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Díaz L, Griffith EEH, editors. Clinical guidelines in cross-cultural mental health. New York: Wiley; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Council of National Psychological Associations for the Advancement of Ethnic Minority Interests. Psychological treatments of ethnic minority populations. Washington, DC: Association of Black Psychologists; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Domenech-Rodríguez M, Wieling E. Developing culturally appropriate evidence based treatments for interventions with ethnic minority populations. In: Rastogi M, Wieling E, editors. Voices of color: First person accounts of ethnic minority therapists. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. pp. 313–333. [Google Scholar]

- Falicov CJ. Cultural perspectives in family therapy. Rockville, MD: Aspen Systems; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Falicov CJ. Latino families in therapy: A guide to multicultural practice. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fraenkel P. Engaging families as experts: Collaborative family program development. Family Process. 2006;45:237–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imber-Black E. Families and larger systems: A family therapist’s guide through the labyrinth. New York: Guilford Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Jalali B. Ethnicity, cultural adjustment, and behavior: Implications for family therapy. In: Comas-Díaz L, Griffith EEH, editors. Clinical guidelines in cross-cultural mental health. Oxford, England: Wiley; 1988. pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kluckhohn F. Variations in the basic values of family systems. Social Casework. 1958;39:63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kluckhohn F, Strodbeck FL. Variations in value orientations. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. Chinese families. In: McGoldrick M, Giordano J, Pearce J, editors. Ethnicity and family therapy. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. pp. 249–267. [Google Scholar]

- López SR, Grover KP, Holland D, Johnson MJ, Kain CD, Kanel K, et al. Development of culturally sensitive psychotherapists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1989;20:369–376. [Google Scholar]

- Matos M, Torres R, Santiago R, Jurado M, Rodríguez I. Adaptation of parent-child interaction therapy for Puerto Rican families: A preliminary study. Family Process. 2006;45:205–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Albee GW. Psychotherapy and ethnic minorities. In: Freedheim DK, Freudenberger HJ, editors. History of psychotherapy: A century of change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1992. pp. 552–570. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel SH, Lusterman D-D, Philpot CL. Casebook for integrating family therapy: An ecosystemic approach. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McGoldrick M, Giordano J, Pearce JK. Ethnicity and family therapy. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- McGoldrick M, Pearce JK, Giordano J. Ethnicity and family therapy. New York: Guilford Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Nakamura R, Bernal G. Including ethnic minorities in mental health intervention research: A practical approach to a long-standing problem. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 2003;27:467–486. doi: 10.1023/b:medi.0000005484.26741.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalvo B, Gutierrez M, Falicov CJ. In Family transitions: Continuity and change over the life cycle. New York: Guilford Press; 1988. The emphasis on cultural identity: A developmental-ecological constraint; pp. 181–209. [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama Hall G. Psychotherapy research with ethnic minorities: Empirical, ethical, and conceptual issues. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:502–510. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Advisory Mental Health Council. Blueprint for change: Research on child and adolescent mental health. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Mental Health; 2001. (Report of the National Advisory Mental Health Council’s Work-group on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment) [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine. Glossary of clinical trial terms. 2006 Retrieved January 10, 2006, from http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct/info/glossary.

- Onken LS, Blaine JD, Battjes R. Behavioral therapy research: A conceptualization of a process. In: Henngler SW, Amentos R, editors. Innovative approaches from difficult to treat populations. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. pp. 477–485. [Google Scholar]

- Pendersen PD. Cross-cultural counseling: Developing culture-centered interactions. In: Bernal G, Trimble JE, Burlew AK, Leong FTL, editors. Handbook of racial and ethnic minority psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 487–503. [Google Scholar]

- Ponterotto JG, Casas JM, Suzuki LA, Alexander CM. Handbook of multicultural counseling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, Onken LS. A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;8:133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Suarez-Morales L, Robbins MS, Szapocznik J. Brief strategic family therapy: Lessons learned in efficacy research and challenges to blending research and practice. Family Process. 2006;45:259–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00094.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel J. Transactions: The interplay between individual, family, and society. New York: Science House; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Arendondo P, McDavis RJ. Multicultural counseling competencies and standards: A call to the profession. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1992;70:477–486. [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Torino GC. Racial-cultural competence: Awareness, knowledge, and skills. In: Carter RT, editor. Handbook of racial-cultural psychology and counseling: Training and practice. Vol. 2. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2005. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Zane N. The role of culture and cultural techniques in psychotherapy: A critique and reformulation. American Psychologist. 1987;42:37–45. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.42.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. Projections of the total resident population by 5-year age groups, race, and Hispanic origin with special age categories. Middle series, 2050 to 2070. 2001 Retrieved January 29, 2006, from http://www.census.gov/population/projections/nation/summary/np-t4-g.txt.

- Uebelacker LA, Hecht J, Miller IW. The Family Check-Up: A pilot study of a brief intervention to improve family functioning in adults. Family Process. 2006;45:223–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman A, Duarte E, Koneru V, Wasserman S. The development of a culturally informed, family-focused treatment for schizophrenia. Family Process. 2006;45:171–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]