Abstract

About 1 to 2% of Clostridium perfringens isolates carry the enterotoxin gene (cpe) necessary for causing C. perfringens type A food poisoning. While the cpe gene can be either chromosomal or plasmid borne, food poisoning isolates usually carry a chromosomal cpe gene. Previous studies have linked this association between chromosomal cpe isolates (i.e., C-cpe isolates) and food poisoning, at least in part, to both the spores and vegetative cells of C-cpe isolates being particularly resistant to high and low temperatures. The current study now reveals that the resistance phenotype of C-cpe isolates extends beyond temperature resistance to also include, for both vegetative cells and spores, enhanced resistance to osmotic stress (from NaCl) and nitrites. However, by omitting one outlier isolate, no significant differences in pH sensitivity were detected between the spores or vegetative cells of C-cpe isolates versus isolates carrying a plasmid-borne cpe gene. These results indicate that both vegetative cells and spores of C-cpe isolates are unusually resistant to several food preservation approaches in addition to temperature extremes. The broad-spectrum nature of the C-cpe resistance phenotype suggests these bacteria may employ multiple mechanisms to persist and grow in foods prior to their transmission to humans.

Clostridium perfringens type A food poisoning currently ranks as the third most common food-borne illness in the United States (11). The gastrointestinal symptoms of this food-borne illness are caused by type A isolates that produce C. perfringens enterotoxin (CPE) (12, 16). While the gene (cpe) encoding the enterotoxin can be either chromosomal or plasmid borne, food poisoning typically is caused by type A isolates carrying a chromosomal cpe gene (4, 5, 13, 14, 20). The strong involvement of chromosomal cpe isolates (i.e., C-cpe isolates) in food poisoning is not due to those isolates producing larger amounts of CPE or a more potent CPE (3, 18). In fact, type A plasmid cpe isolates (i.e., P-cpe isolates) are competent human enteropathogens, as they can cause such non-food-borne human gastrointestinal illnesses as antibiotic-associated diarrhea.

Recent studies have suggested that the association between C-cpe isolates and food poisoning may result from non-toxin-related characteristics that make C-cpe isolates particularly well suited for survival and growth in the food poisoning environment. For example, a recent year-long survey (19) of numerous, independent Pittsburgh area food stores reported that 13 of 13 cpe-positive isolates recovered from retail meats, poultry, and fish carry a chromosomal cpe gene rather than a plasmid cpe gene. This finding indicates that C-cpe isolates are the predominant cause of C. perfringens type A food poisoning, at least in part because they are the most abundant cpe-positive isolates present in the food vehicles causing this food poisoning.

Since the foods sampled in the Pittsburgh area retail food survey (19) were predominantly raw meats, poultry, and fish stored under refrigeration, another recent study (10) compared the growth and survival of C-cpe isolates versus P-cpe isolates under refrigeration or commercial freezer temperatures. Those studies (10) revealed that at 4°C or −20°C the vegetative cells of C-cpe isolates exhibit, respectively, ∼8-fold- or 3-fold-higher decimal reduction values (D values, i.e., the time a culture must be held at a given temperature to obtain a 90% reduction in viable cell number) compared to the vegetative cells of P-cpe isolates. Additionally, upon 6 months of incubation at 4°C or −20°C, spores of C-cpe isolates exhibited, respectively, an ∼4-fold- or ∼3-fold-lower reduction in viability compared to spores of P-cpe isolates. Those observations suggested that the more common presence of C-cpe isolates versus P-cpe isolates in refrigerated meat, poultry, and fish is attributable, at least in part, to the vegetative cells and spores of C-cpe isolates having better low-temperature resistance than the cells or spores of P-cpe isolates, i.e., even when P-cpe isolates contaminate foods, those bacteria may not survive if the food is stored at 4°C or −20°C. Besides exhibiting better low-temperature survival, C-cpe isolates were also found to grow at lower minimum temperatures than P-cpe isolates, which could help them multiply to pathogenic levels in foods stored in malfunctioning or improperly set refrigerators, for example.

However, greater survival and growth abilities at low temperatures are not the only food poisoning-relevant phenotypic differences between type A C-cpe isolates versus type A P-cpe isolates. At least two labs (1, 17) have now demonstrated that the vegetative cells and spores of C-cpe isolates are typically more heat resistant than the cells or spores of P-cpe isolates. For example, vegetative cells of C-cpe isolates were found to exhibit, on average, a twofold higher D value at 55°C compared to the vegetative cells of P-cpe isolates (17). Even greater heat resistance differences were noted (17) between the spores of C-cpe versus P-cpe isolates, with spores of C-cpe isolates exhibiting, on average, nearly 60-fold-higher D values at 100°C compared to the spores of P-cpe isolates. C-cpe isolates can also grow at higher maximum temperatures than P-cpe isolates (10). The greater heat tolerance, for both survival and growth, of cells and spores of C-cpe isolates may further explain the association of these isolates with food poisoning, since better survival and growth at elevated temperatures should favor the ability of C-cpe isolates to cause food poisoning via incompletely cooked or improperly warmed foods.

While important, application of high or low temperature is not the only approach used to control the growth of food-borne pathogens in foods. Manipulations of osmolarity and pH, as well as addition of chemical preservatives such as nitrites, are also important food safety approaches (6). Therefore, the current study evaluated differences that exist between the sensitivities of vegetative cells and spores of C-cpe isolates versus P-cpe isolates to osmotic, nitrite-induced, and pH-induced stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

This study used the same eight C-cpe type A isolates, seven P-cpe type A isolates, and four cpe-negative C. perfringens type A isolates that we have previously characterized for their heat resistance, cold resistance, and growth properties (10, 17). The origin of these 19 C. perfringens isolates has been described previously (17). All isolates were routinely maintained as cooked meat medium (Oxoid) stock cultures, which were stored at −20°C.

Comparison of C. perfringens vegetative cell growth in the presence of osmotic, nitrite-induced, or pH-induced stress.

A starter culture of each surveyed C. perfringens type A isolate was prepared by inoculating 0.1 ml of a cooked meat medium stock culture into 6 ml of fluid thioglycolate broth (FTG; Difco). After overnight growth of the starter culture at 37°C, a 0.2-ml culture aliquot was inoculated into 6 ml of fresh FTG medium, which was then grown for 2 h at 37°C. After mixing, a 0.1-ml aliquot of each 2-h FTG culture was serially diluted (at dilutions from 10−2 to 10−7) with sterile water. The diluted samples were then plated onto brain heart infusion agar (BHIA; BD Biosciences), and those plates were incubated overnight in a GasPak anaerobe jar to determine the total number of vegetative cells present in each FTG culture prior to the introduction of osmotic, nitrite, or pH stress. To evaluate the effects of those stresses on vegetative cell growth, aliquots of the same diluted samples were plated onto BHIA supplemented with one of the following: (i) for osmotic stress experiments, BHIA (which itself contains ∼0.5% NaCl) was supplemented with an additional 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4% NaCl; (ii) for nitrite stress experiments, BHIA was supplemented with 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, or 0.4% NaNO2 (which was dissolved separately and filter sterilized with a 0.45-μm Millipore filter); (iii) for the pH stress experiments, the pH of BHIA (normally 7.6) was adjusted (using either sterile 1 M HCl or 1 M NaOH) to pH 4.8, 5.0, 5.2, 5.4, 8.0, 8.5, 9.0, 9.5, or 10.0 after autoclaving. The addition of NaCl or NaNO2 did not affect the pH of BHIA.

After overnight incubation, CFU values were determined for the above plates, and those results were graphed to determine the effects of each stress condition on growth.

Comparison of C. perfringens vegetative cell survival in the presence of osmotic, nitrite-induced, or pH-induced stress.

To compare vegetative cell survival for C-cpe isolates versus P-cpe isolates under potentially stressful osmotic, nitrite, or pH incubation conditions, a 2-h FTG culture of each surveyed C. perfringens isolate was prepared from an FTG starter culture and the total number of vegetative bacteria present at day zero was determined, as described above. The remainder of each 2-h culture was then mixed and divided into 1-ml aliquots. Those aliquots were centrifuged, and the pellets were washed with one of the following solutions: standard FTG (pH 7.6), FTG supplemented with an additional 2.5% NaCl, FTG supplemented with 0.2% NaNO2, FTG adjusted to pH 5.5, or FTG adjusted to pH 9.5. Each washed pellet was then resuspended in the same modified FTG used for washing (these conditions were chosen on the basis of growth experiment results [see Fig. 1, below] to provide substantial bacterial killing within 4 days). Those samples were incubated at room temperature for up to 4 days. At defined time intervals, a 0.1-ml aliquot was removed from one tube of each sample, diluted (dilution range from 10−2 to 10−7) with sterile water, and then immediately plated onto standard BHIA. After an overnight anaerobic incubation, colonies on each BHIA plate were counted and the CFU values obtained were then graphed to determine the effects on survival of each type of stress.

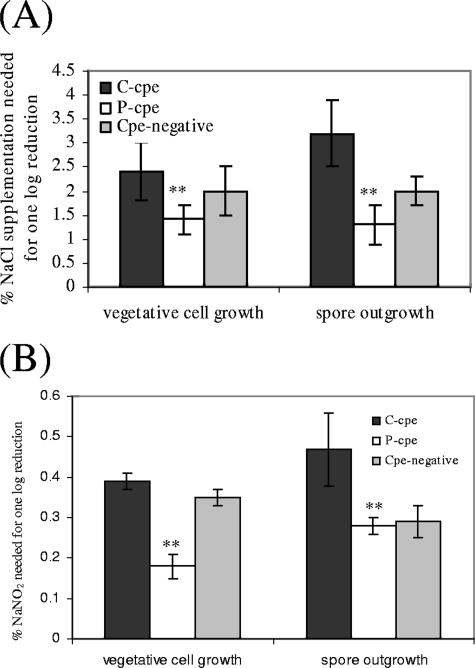

FIG. 1.

Effects of supplemental NaCl or NaNO2 on vegetative cell growth or spore outgrowth for C. perfringens type A isolates carrying chromosomal or plasmid-borne cpe genes. The average concentration of supplemental NaCl (A) or NaNO2 (B) needed to cause a 1-log reduction in vegetative growth (left) or spore outgrowth (right) is shown for eight type A C-cpe isolates, seven type A P-cpe isolates, and four cpe-negative isolates. For each treatment, the concentration of supplemental NaCl or NaNO2 needed to reduce vegetative growth or spore outgrowth by 1 log was determined in two independent experiments for each isolate, as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars indicate standard deviations, while double asterisks indicate differences that were statistically significant at P values of <0.01.

Determination of the effects of osmotic, NaNO2-induced, or pH-induced stress on C. perfringens spore survival or outgrowth.

A 0.2-ml aliquot of a starter FTG culture (prepared as described above) was inoculated into 10 ml of Duncan-Strong (DS) sporulation medium (7). After overnight incubation at 37°C, the presence of sporulating cells in each DS culture was confirmed by phase-contrast microscopy. Following mixing, each sporulating DS culture was heat shocked at 75°C for 20 min to kill any remaining vegetative cells and to promote subsequent spore germination and outgrowth. A 0.1-ml aliquot of each heat-shocked DS culture was then serially diluted (dilution range from 10−2 to 10−7) with sterile water. Those diluted samples were plated onto BHIA plates, which were then incubated anaerobically overnight at 37°C to determine the total number of spores in each DS culture that were capable of outgrowth in the absence of osmotic, NaNO2-induced, or pH-induced stress.

To determine the sensitivity of spore outgrowth to potentially stressful NaNO2 or osmotic conditions, we used BHIA plates containing supplemental NaCl or NaNO2, as described above for experiments evaluating C. perfringens vegetative cell growth in the presence of these two stresses. Similarly, the pH sensitivity of outgrowing spores was evaluated using BHIA plates with an adjusted pH, as also described above for vegetative growth experiments. After overnight anaerobic incubation, CFU values for each plate were graphed to determine the effects of pH or supplemental NaCl or NaNO2 on spore outgrowth for each surveyed C. perfringens isolate.

To evaluate spore survival under osmotic, nitrite, or pH stress, a DS culture was divided into several small tubes, which were washed with one of the following: standard FTG; FTG supplemented with 5% NaCl, pH 7.6; FTG supplemented with 0.5% NaNO2, pH 7.6; FTG adjusted to a pH of 4; FTG adjusted to pH 10. After washing, the bacteria were resuspended in the same modified FTG used for washing and the resuspended bacteria were then aliquoted into 1-ml tubes, which were incubated at room temperature. To assess the effects of osmotic stress on spore survival, 0.1-ml aliquots were removed at 2-month intervals (for up to 6 months) from the tubes containing bacteria suspended in FTG supplemented with 5% NaCl, pH 7.6. To assess the effects of spore incubation in FTG containing 0.5% NaNO2, FTG adjusted to pH 4, or FTG adjusted to pH 10 on spore survival, 0.1-ml aliquots were removed from the appropriate tubes every month, for up to 3 months. After an aliquot was withdrawn, the tube was sterilized and discarded. Removed aliquots were heat shocked at 75°C for 20 min and then diluted (from 10−2 to 10−7) with sterile water. Each dilution was immediately plated onto standard BHIA plates, which were anaerobically incubated overnight at 37°C. Colonies on each BHIA plate were counted the next morning to determine the number of viable spores that had been present per milliliter of culture at each measured time point for each stress treatment. Those values were then graphed to determine the log reduction in viable spores over 3 or 6 months for each C. perfringens isolate.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Student t test.

RESULTS

Effects of supplemental NaCl or NaNO2 on vegetative cell growth of C-cpe versus P-cpe isolates.

In studies assessing the effects of NaCl on C. perfringens vegetative growth, supplementation of BHIA with <1.5% of additional NaCl was found to cause, on average, a 1-log reduction in growth of seven P-cpe isolates (Fig. 1A). In contrast, BHIA had to be supplemented with nearly 2.5% of additional NaCl to cause an average 1-log drop in growth of eight C-cpe isolates. These osmotic sensitivity differences were statistically significant at P < 0.01. Similarly, the addition of <0.2% NaNO2 to BHIA was sufficient to cause, on average, a 1-log reduction in growth of the surveyed C. perfringens plasmid cpe isolates (Fig. 1B). However, nearly 0.4% NaNO2 had to be added to BHIA to reduce the average growth of eight C-cpe isolates by 1 log. These differences were also statistically significant at P < 0.01. There was no overlap in sensitivity to either NaCl supplementation or NaNO2 between vegetative cell growth of C-cpe isolates versus P-cpe isolates. That is, vegetative cells of the most sensitive C-cpe isolates still grew at higher concentrations of supplemental NaCl or NaNO2 than did vegetative cells of the most resistant P-cpe isolates.

For comparison, four cpe-negative isolates showed, relative to the 15 surveyed type C-cpe or P-cpe isolates, intermediate growth sensitivity to supplemental NaCl or NaNO2 (Fig. 1A and B).

Effects of supplemental NaCl or NaNO2 on vegetative cell survival for type A C-cpe isolates versus P-cpe isolates.

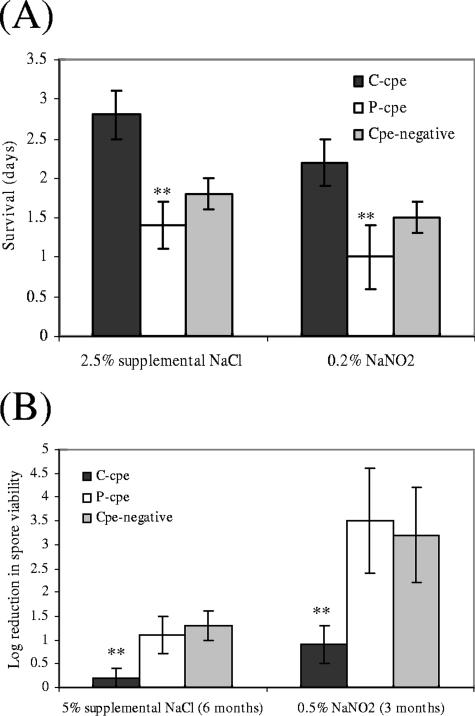

In experiments evaluating C. perfringens vegetative cell survival in FTG supplemented with 2.5% additional NaCl, a 1.5-day incubation was sufficient to cause an average 1-log reduction in vegetative cell viability for the seven surveyed P-cpe isolates (Fig. 2A). However, the eight surveyed C-cpe isolates had to be incubated in this medium for nearly twofold longer to obtain a similar 1-log reduction in vegetative cell viability. These differences in osmotic stress survival were statistically significant at P < 0.01. Similarly, prior to reaching a 1-log reduction in their vegetative cell viability, these eight C-cpe isolates survived, on average, nearly twofold longer in FTG containing 0.2% NaNO2 compared to the seven surveyed P-cpe isolates (Fig. 2B). These differences were also statistically significant at P < 0.01. In the presence of supplemental NaCl or NaNO2, no overlap was noted between vegetative cell survival of C-cpe isolates versus P-cpe isolates. That is, vegetative cells of the least resistant C-cpe isolates survived longer than vegetative cells of the most resistant P-cpe isolates before reaching a 1-log reduction in viability.

FIG. 2.

Effects of supplemental NaCl or NaNO2 on vegetative cell (A) or spore (B) survival for C. perfringens type A isolates carrying chromosomal or plasmid-borne cpe genes. (A) Average number of days of incubation in FTG supplemented with either 2.5% additional NaCl (left panel) or FTG containing 0.2% NaNO2 (right panel) needed to a cause a 1-log reduction in viability of vegetative cell cultures for eight type A C-cpe isolates, seven type A P-cpe isolates, or four cpe-negative isolates. (B) Average log reduction in viable spores upon incubation for 6 months in FTG containing 5% supplemental NaCl (left panel) or for 3 months in FTG containing 0.5% NaNO2 (right panel) for eight type A C-cpe isolates, seven type A P-cpe isolates, and four type A cpe-negative isolates. For both panels, results shown are from two independent experiments for each isolate, as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars indicate standard deviations, while double asterisks indicate differences that were statistically significant at P values of <0.01.

For comparison, survival times in the presence of 2% supplemental NaCl or 0.2% NaNO2 for four cpe-negative isolates were found to be intermediate between the results obtained for the C-cpe isolates and P-cpe isolates (Fig. 2A and B).

Effects of supplemental NaCl or NaNO2 on spore outgrowth for C-cpe versus P-cpe isolates.

Experiments studying the effects of NaCl on C. perfringens spore outgrowth revealed that supplementation of BHIA with ∼1.5% of additional NaCl caused, on average, a 1-log reduction in spore outgrowth for seven P-cpe isolates (Fig. 1A). In contrast, nearly twice as much supplemental NaCl had to be added to BHIA to produce an average 1-log drop in spore germination and outgrowth for eight C-cpe isolates. These differences in spore outgrowth sensitivity to osmotic stress were statistically significant at P < 0.01. Similarly, Fig. 1B results indicate that the addition of <0.2% NaNO2 to BHIA caused, on average, a 1-log reduction in spore outgrowth for the surveyed P-cpe isolates. However, approximately twice as much NaNO2 had to be added to BHIA to produce an average 1-log reduction in spore outgrowth for the eight C-cpe isolates. These differences were also statistically significant at P < 0.01. In these experiments, no overlap in the sensitivity of spore outgrowth to NaCl supplementation or NaNO2 was noted between the surveyed C-cpe isolates versus P-cpe isolates. That is, spore outgrowth of the most sensitive C-cpe isolates occurred at higher concentrations of supplemental NaCl or NaNO2 than did spore outgrowth of the most resistant P-cpe isolates.

For comparison, relative to the 15 surveyed type A C-cpe isolates and P-cpe isolates, 4 cpe-negative isolates exhibited (Fig. 1A and B) intermediate spore outgrowth sensitivity to supplemental NaCl or NaNO2 (data not shown).

Effects of supplemental NaCl or NaNO2 on spore survival for C-cpe versus P-cpe isolates.

All surveyed C. perfringens spores were resistant to osmotic stress; even after 6 months, the spores of many isolates incubated in FTG supplemented with 5% additional NaCl had not yet reached a 1-log reduction in their viability. Therefore, formal D values could not be calculated for these experiments. Nevertheless, 6-month incubation in FTG supplemented with 5% additional NaCl caused (on average) nearly a fivefold-higher log reduction in viability of spores produced by P-cpe isolates compared to spores of C-cpe isolates (Fig. 2B). Similarly, spores of P-cpe isolates showed, on average, nearly a fourfold-higher log reduction in viability compared to spores from C-cpe isolates when incubated for 3 months in FTG containing 0.5% NaNO2 (Fig. 2B). These spore survival differences for C-cpe isolates versus P-cpe isolates in the presence of supplemental NaCl or NaNO2 were statistically significant (P < 0.01).

Notably, whether incubated in supplemental NaCl or NaNO2, no overlap in spore survival results was observed between the surveyed C-cpe versus P-cpe isolates. That is, spores from the most sensitive C-cpe isolates were still more resistant to osmotic or nitrite-induced stress than were spores of the most resistant P-cpe isolates. For comparison, spores of the four cpe-negative isolates were shown to exhibit a similar reduction in viability in the presence of supplemental NaCl or NaNO2 as did spores of the surveyed P-cpe isolates (Fig. 2B).

Effects of pH on vegetative cell growth and survival or spore outgrowth and survival for C-cpe isolates versus P-cpe isolates.

The lowest pH supporting vegetative growth of C-cpe or P-cpe isolates was 5.1 ± 0.1 or 5.2 ± 0.1, respectively; those slight pH sensitivity differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.1). The highest pH supporting vegetative cell growth was 9.7 ± 0.3 for C-cpe isolates or 9.3 ± 0.4 for P-cpe isolates, but those basic pH sensitivity differences were also not statistically significant (P > 0.05). In terms of vegetative cell survival at low or high pH, C-cpe vegetative cells survived for 1.9 ± 0.4 or 3.4 ± 0.7 days in FTG adjusted to pH 5.5 or pH 9.5, respectively, before exhibiting an average 1-log reduction in viability. Similarly, vegetative cells of P-cpe isolates survived, on average, for 1.4 ± 0.5 or 3.1 ± 0.9 days in FTG adjusted to pH 5.5 or pH 9.5 prior to exhibiting an average 1-log reduction in viability. Neither of those differences in pH survival between vegetative cells of C-cpe isolates versus P-cpe isolates were statistically significant (P > 0.05 for pH 5.5 results and P > 0.6 for pH 9.5 results).

In studies performed to assess the effects of pH on spore outgrowth, spores of C-cpe isolates exhibited outgrowth down to a pH of 5.1 ± 0.1 or up to a pH of 9.9 ± 0.2. Similarly, P-cpe isolates exhibited outgrowth down to a pH of 5.2 ± 0.1 and up to a pH of 9.8 ± 0.4. These slight differences in spore outgrowth sensitivity to pH were not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

When evaluating pH effects on spore survival, spores of both C-cpe and P-cpe isolates exhibited only a 0.2-log reduction in viability after 3 months of incubation in FTG, pH 7. However, spores of C-cpe or P-cpe isolates survived less well at pH 4 or 10 than at pH 7. At pH 10, a 0.8 ± 0.2 or 1.0 ± 0.4 log reduction in survival of spores of C-cpe or P-cpe isolates, respectively, was observed after 3 months of incubation. Those slight spore survival differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.1). Spores of C-cpe or P-cpe isolates exhibited, respectively, a 1.2 ± 0.3 versus 2.2 ± 0.8 log decrease in viability after 3 months of incubation at pH 4; these low pH survival differences had borderline statistical significance (P ∼ 0.05) if an outlier P-cpe isolate was included whose spores were exceptionally sensitive to low pH, showing a 3.6-log viability decrease after 3 months of incubation at pH 4. If that outlier isolate is disregarded, the low-pH spore survival differences between C-cpe and P-cpe isolates were not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Temperature abuse of foods is considered the major contributing factor to C. perfringens type A food poisoning outbreaks. Previous studies (1, 10, 17) have shown that, in terms of both growth and survival, C-cpe isolates are particularly tolerant of heating, refrigeration, and freezing. However, other factors, such as water activity, pH, and the presence of preservatives (such as nitrites) probably also play a role in suppressing C. perfringens growth in foods (6, 8). Supporting this view, for example, is the very low incidence of C. perfringens type A food poisoning outbreaks that involve cured meats (8). For example, from 1978 to 1992, only two recognized C. perfringens type A food poisoning outbreaks were caused by contaminated ham (8). Similarly, recent CDC statistics (2) fail to implicate contaminated ham as the food vehicle responsible for a single C. perfringens type A food poisoning outbreak in the United States during the period 2002 to 2004. Suppression of C. perfringens in foods by curing is also consistent with results from a recent survey (19) of Pittsburgh retail foods, which detected the presence of C. perfringens in a variety of raw, noncured meat, poultry, and seafood items, but not in ham. Therefore, our current results demonstrating that, relative to plasmid cpe isolates, the spores and vegetative cells of C-cpe isolates are particularly resistant to osmotic and nitrite-induced stress offer further explanations for the association of C-cpe isolates with food poisoning.

With respect to osmotic tolerance, our current study found that vegetative cells of C-cpe isolates grow and survive at significantly higher NaCl concentrations than do the vegetative cells of P-cpe isolates. Our finding that the growth and survival of cpe-negative C. perfringens isolates show intermediate NaCl sensitivity lying between those of C-cpe isolates and P-cpe isolates further supports the C-cpe isolates as being particularly tolerant of osmotic stress, although the physiologic mechanism of this resistance remains to be defined. NaCl, which exerts its antimicrobial activity primarily by lowering the water activity of the external medium to subject bacterial cells to osmotic shock and loss of water through plasmolysis (6, 8), was chosen for these osmotic stress studies because it is probably the oldest food preservative and is still important for preservation of cured meats and some other foods. However, future studies should assess whether C-cpe isolates are also more tolerant than P-cpe isolates to osmotic stress from other food preservative agents (e.g., sucrose).

Interestingly, spores of C-cpe isolates also exhibited significantly better NaCl tolerance for survival and outgrowth compared to the spores of P-cpe isolates or cpe-negative isolates, i.e., spores of C-cpe isolates also appear to be particularly resistant to osmotic stress for survival and outgrowth, although it is unclear if this involves the same (yet-unidentified) osmotic resistance mechanism used by vegetative cells. While the osmotic tolerance of spores produced by P-cpe isolates has not been previously assessed, the 1-log reduction in spore outgrowth determined for our surveyed C-cpe isolates at ∼3 to 4% NaCl is similar to previous reports (21) examining outgrowth of three C-cpe isolates in ham supplemented with NaCl. Given that spores are essentially free of internal water, it is not surprising that NaCl had only modest effects on spore viability for all our surveyed C. perfringens isolates. Nevertheless, it is potentially important for food safety that spores of C-cpe isolates survive hypertonic conditions better than other C. perfringens spores.

Nitrites are an important class of food preservatives, particularly for cured meats (6, 8). The principle antimicrobial use of nitrites is to inhibit outgrowth of clostridial spores, although high concentrations can also kill spores (6, 8). Our current results confirm the ability of nitrite to inhibit outgrowth and survival of C. perfringens spores. More importantly for food safety, relative to both P-cpe and cpe-negative isolates, we found that the spores of C-cpe isolates are particularly tolerant of nitrite. Although the nitrite sensitivity of P-cpe isolates had not (to our knowledge) been examined previously, the concentrations of nitrite found in the current study to inhibit spore outgrowth for C-cpe isolates at pH 7 resemble observations reported previously for two C-cpe isolates (9). We also found that vegetative cells of C-cpe isolates are particularly nitrite resistant for both their growth and survival. Previous studies (6) have shown that nitrites can inhibit a number of clostridial enzymes and factors, such as ferredoxin, so it is possible that some of these nitrite targets have been modified in C-cpe isolates, allowing better tolerance and survival in the face of nitrite-induced stress.

In contrast to their consistently superior tolerance of osmotic and nitrite-induced stress, the spores and vegetative cells of C-cpe isolates showed only modestly better pH tolerance compared to P-cpe isolates or cpe-negative isolates, with none of those pH tolerance differences reaching statistical significance (if an outlier P-cpe isolate was omitted). To our knowledge, there have not been previous studies of pH effects on C. perfringens spore survival or of the mechanisms behind pH-induced killing of C. perfringens spores. However, the pH sensitivity determined in our study for vegetative growth of the surveyed C. perfringens isolates generally resembles previous reports in the literature (8), although the cpe genotypes of isolates used in those previous studies were generally not reported.

The significantly greater resistance of vegetative cells and spores of C-cpe isolates to osmotic and nitrite-induced stress, as identified in this study, could be important for survival and growth of C-cpe isolates in foods prior to transmission to humans. In particular, these observations contribute to the emerging view indicating that the C-cpe isolates responsible for most food poisoning outbreaks are not merely passive bacterial toxin delivery platforms but are themselves highly adapted for their role as a food-borne pathogen. Further studies of the resistance phenotype of C-cpe isolates are clearly needed. For example, since food preservation factors can act synergistically (8, 15), additional studies in which multiple preservation conditions (e.g., temperature, pH, and nitrites) are varied should be performed to fully characterize the resistance phenotype of the spores and vegetative cells of C-cpe isolates. In addition, the specific mechanisms used by vegetative cells and spores of C-cpe isolates to resist temperature-induced, osmotic, and nitrite-induced stress need to be identified, perhaps by proteomics. In this regard, our observation that both the vegetative cells and spores of C-cpe isolates exhibit a broad resistance phenotype to many food-associated stresses could indicate the resistance properties of C-cpe isolates are complicated and multifactorial. Finally, the broad-spectrum resistance phenotype of C-cpe isolates highlights the need to use these specific isolates for food microbiology studies of C. perfringens and for establishing food safety control parameters.

Acknowledgments

This research was generously supported by National Research Initiative competitive grant 2005-53201-15387 from the USDA Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 October 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen, K. G., T. B. Hansen, and S. Knochel. 2004. Growth of heat-treated enterotoxin-positive Clostridium perfringens and the implications for safe cooling rates. J. Food Prot. 67:83-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2006. Annual listing of foodborne disease outbreaks, United States, 1990-2004. [Online.] http://www.cdc.gov/foodborneoutbreaks/outbreak_data.htm.

- 3.Collie, R. E., J. F. Kokai-Kun, and B. A. McClane. 1998. Phenotypic characterization of enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens isolates from non-foodborne human gastrointestinal diseases. Anaerobe 4:69-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collie, R. E., and B. A. McClane. 1998. Evidence that the enterotoxin gene can be episomal in Clostridium perfringens isolates associated with non-food-borne human gastrointestinal diseases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:30-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornillot, E., B. Saint-Joanis, G. Daube, S. Katayama, P. E. Granum, B. Carnard, and S. T. Cole. 1995. The enterotoxin gene (cpe) of Clostridium perfringens can be chromosomal or plasmid-borne. Mol. Microbiol. 15:639-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle, M. P., L. R. Beuchat, and T. J. Montville. 2001. Food microbiology: fundamentals and frontiers. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 7.Kokai-Kun, J. F., J. G. Songer, J. R. Czeczulin, F. Chen, and B. A. McClane. 1994. Comparison of Western immunoblots and gene detection assays for identification of potentially enterotoxigenic isolates of Clostridium perfringens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2533-2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Labbe, R. G. 1989. Clostridium perfringens, p. 192-234. In M. P. Doyle (ed.), Foodborne bacterial pathogens. Marcel Dekker, New York, N.Y.

- 9.Labbe, R. G., and C. L. Duncan. 1970. Growth from spores of Clostridium perfringens in the presence of sodium nitrite. Appl. Microbiol. 19:353-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li, J., and B. A. McClane. 2006. Further comparison of temperature effects on growth and survival of Clostridium perfringens type A isolates carrying a chromosomal or plasmid-borne enterotoxin gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:4561-4568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McClane, B. A. 2001. Clostridium perfringens, p. 351-372. In M. P. Doyle, L. R. Beuchat, and T. J. Montville (ed.), Food microbiology: fundamentals and frontiers, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 12.McClane, B. A. 2000. Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin and intestinal tight junctions. Trends Microbiol. 8:145-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyamoto, K., G. Chakrabarti, Y. Morino, and B. A. McClane. 2002. Organization of the plasmid cpe locus of Clostridium perfringens type A isolates. Infect. Immun. 70:4261-4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyamoto, K., Q. Wen, and B. A. McClane. 2004. Multiplex PCR genotyping assay that distinguishes between isolates of Clostridium perfringens type A carrying a chromosomal enterotoxin gene (cpe) locus, a plasmid cpe locus with an IS1470-like sequence, or a plasmid cpe locus with an IS1151 sequence. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1552-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novak, J. S., and J. T. C. Yuan. 2003. Viability of Clostridium perfringens, Escherichia coli, and Listeria monocytogenes surviving mild heat or aqueous ozone treatment on beef followed by heat, alkali, or salt stress. J. Food Prot. 66:382-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarker, M. R., R. J. Carman, and B. A. McClane. 1999. Inactivation of the gene (cpe) encoding Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin eliminates the ability of two cpe-positive C. perfringens type A human gastrointestinal disease isolates to affect rabbit ileal loops. Mol. Microbiol. 33:946-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarker, M. R., R. P. Shivers, S. G. Sparks, V. K. Juneja, and B. A. McClane. 2000. Comparative experiments to examine the effects of heating on vegetative cells and spores of Clostridium perfringens isolates carrying plasmid versus chromosomal enterotoxin genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3234-3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 18.Sparks, S. G., R. J. Carman, M. R. Sarker, and B. A. McClane. 2001. Genotyping of enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens isolates associated with gastrointestinal disease in North America. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:883-888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen, Q., and B. A. McClane. 2004. Detection of enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens type A isolates in American retail foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2685-2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen, Q., K. Miyamoto, and B. A. McClane. 2003. Development of a duplex PCR genotyping assay for distinguishing Clostridium perfringens type A isolates carrying chromosomal enterotoxin (cpe) genes from those carrying plasmid-borne enterotoxin (cpe) genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1494-1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaika, L. L. 2003. Influence of NaCl content and cooling rate on outgrowth of Clostridium perfringens spores in cooked ham and beef. J. Food Prot. 66:1599-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]