Abstract

The aim of this investigation was to exploit the vast comparative data generated by comparative genome hybridization (CGH) studies of Campylobacter jejuni in developing a genotyping method. We examined genes in C. jejuni that exhibit binary status (present or absent between strains) within known plasticity regions, in order to identify a minimal subset of gene targets that provide high-resolution genetic fingerprints. Using CGH data from three studies as input, binary gene sets were identified with “Minimum SNPs” software. “Minimum SNPs” selects for the minimum number of targets required to obtain a predefined resolution, based on Simpson's index of diversity (D). After implementation of stringent criteria for gene presence/absence, eight binary genes were found that provided 100% resolution (D = 1) of 20 C. jejuni strains. A real-time PCR assay was developed and tested on 181 C. jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates, a subset of which have previously been characterized by multilocus sequence typing, flaA short variable region sequencing, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. In addition to the binary gene real-time PCR assay, we refined the seven-member single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) real-time PCR assay previously described for C. jejuni and C. coli. By normalizing the SNP assay with the respective C. jejuni and C. coli ubiquitous genes, mapA and ceuE, the polymorphisms at each SNP could be determined without separate reactions for every polymorphism. We have developed and refined a rapid, highly discriminatory genotyping method for C. jejuni and C. coli that uses generic technology and is amenable to high-throughput analyses.

Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli continue to persist as the most common etiological agents of human bacterial gastroenteritis worldwide. The sporadic nature of campylobacteriosis in humans, the ubiquitous distribution of Campylobacter spp. in the environment and in certain foodstuffs, and the lack of a well-understood relationship between genotype and pathogenicity render the utility of routine Campylobacter typing a matter of ongoing contention (33). However, typing has demonstrable value in monitoring small-scale Campylobacter outbreaks and for examining the genetic diversity and population biology of the species (5, 7, 14, 16, 19, 45).

While several phenotypic and molecular methods have been developed for characterizing Campylobacter spp., pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) is considered the “gold standard” methodology due to the high degree of resolution obtained with this technique. Despite this, PFGE is limited to specialized applications as it is time-consuming and technically demanding and requires extensive normalization of protocols and genetic profiles to facilitate interlaboratory comparisons (6, 52). In recent years, multilocus sequence typing (MLST) has emerged as a practical approach for examining bacterial epidemiology and population genetics. MLST studies of C. jejuni and C. coli indicate a weakly clonal population structure generated as a result of high-frequency intraspecific recombination (7, 8, 9, 10, 29, 34). The lack of genetic linkage across the Campylobacter genome renders interrogation of multiple loci an effective means of gaining typing resolution, as demonstrated by the addition of the flagellin A short variable region (flaA SVR) locus to MLST (9, 12, 30). Consistent with this observation, MLST-flaA SVR yields resolution comparable to that of PFGE during examination of Campylobacter outbreaks (5, 31, 45).

We have previously pursued a distinctive approach to the development of DNA-based bacterial typing methods, which utilizes computerized analyses of known genetic diversity to identify highly informative sets of polymorphic targets. To date, the software package “Minimum SNPs” has been used to derive minimal sets of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from MLST databases (22, 23, 43, 44, 47). “Minimum SNPs” uses Simpson's index of diversity (D) (21) to measure the resolving power of SNP sets, termed “high-D SNPs,” with reference to the entire MLST database of a bacterium. It has been found that seven high-D SNPs can provide D values of between 0.95 and 0.99, depending on the bacterial species. Bacterial genotyping using real-time PCR has gained substantial popularity in recent years (2, 22, 23, 40, 46, 47), as it provides a flexible, inexpensive, single-step, and rapid means for characterizing an array of polymorphic targets on a single platform. We have previously developed allele-specific (AS) real-time PCR-based methods for interrogating the high-D SNPs of Neisseria meningitidis, Staphylococcus aureus, and C. jejuni (43, 44, 47). AS real-time PCR (also known as kinetic PCR) was chosen because this method places minimal constraints on assay design and does not require labeled primers or probes.

The impetus for the current study was the recognition that “Minimum SNPs” could be used to derive informative sets of targets from databases other than DNA sequence alignments. The ability to compare multiple C. jejuni strains on a whole-genome level using comparative genome hybridization (CGH) DNA microarrays has facilitated identification of gene divergence and conservation patterns throughout the C. jejuni genome (3, 11, 25, 26, 41, 42, 51). Additionally, the determination of entire genome sequences for two C. jejuni strains (15, 39), coupled with similar undertakings for additional Campylobacter species (15), has substantially increased our understanding of these organisms. Genome sequencing and CGH of C. jejuni have revealed a largely colinear genome arrangement with few mobile elements or repeat sequences. Scattered within this stable genome “backbone” are regions consisting of multigene insertions and deletions, termed plasticity regions (PRs). The PRs contain genes involved in lipooligosaccharide, flagellin, and capsular biosynthesis; restriction-modification systems; and a large number of open reading frames with hypothetical or unknown functions (41, 51).

To date, whole-genome DNA arrays have been used to compare gene-to-gene differences between 226 C. jejuni strains. However, for routine genotyping of C. jejuni, genome sequencing and CGH approaches are not feasible. Therefore, the major aim of the current study was to use “Minimum SNPs” to derive from CGH data a minimal set of binary targets (i.e., genes present in some strains but not others, such as those within PRs) from CGH studies that are useful for genotyping.

The second aim of this investigation was to further refine a previously described SNP assay for C. jejuni/C. coli (43). Interrogation of seven highly discriminatory SNPs (identified using D) on the real-time PCR platform with SYBR green I detection, while a cost-effective technology, traditionally requires separate reactions targeting each polymorphism, unlike multiplex-amenable chemistries such as TaqMan (27), LUX (28, 36), or molecular beacons (32). Therefore, we examined a method for reducing the number of reactions required for kinetic PCR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Campylobacter isolates.

The OzFoodNet collection of 152 C. jejuni and two C. coli MLST- and flaA SVR-characterized isolates was used in this study (37, 43). A subset of these isolates (n = 84) have also been subjected to PFGE (37). A further 29 clinical Campylobacter isolates were obtained from the Princess Alexandra Hospital (PAH), Brisbane, Australia, collected between 1992 and 2004. All isolates were obtained from fecal samples of patients presenting with gastroenteric symptoms. Additionally, two well-characterized type culture strains, NCTC 11168 and NCTC 11351, were obtained from the Australian Collection of Microorganisms (Brisbane, Australia). Strains were grown and genomic DNA (gDNA) extracted as previously described (43).

Binary gene selection.

Data generated from three CGH array studies of C. jejuni were used in the analysis (41, 42, 51). Eighteen C. jejuni strains were examined in the study by Pearson et al. (41). In addition, the recently genome-sequenced RM1221 strain (15) and CGH data from ATCC 43431 (42) were included in analyses. The presence or absence of CGH genes in RM1221 was tested in silico using the CampyDB BLAST server at xBASE (http://xbase.bham.ac.uk/ [4]). Binary genes for ATCC 43431 were assigned as “absent” when the array and PCR data were in complete agreement; otherwise, the genes were converted to “present” by default to minimize the effects of moderately divergent genes on the array signal (42).

The “Minimum SNPs” v2.042 software, described elsewhere (43, 44), was used to identify the minimal number of gene targets required for maximal resolution of the 20 C. jejuni isolates. As “Minimum SNPs” was designed to accept data in nucleotide format, the CGH data required conversion into concatenated nucleotide format. To achieve this, “A” was used to designate the absence of a gene within a strain, whereas “T” represented the presence of a gene. Once the data were converted to nucleotide format, the D function of “Minimum SNPs” (44) was used to find minimal gene sets.

Binary gene detection.

Specific primers for each of the binary genes were identified using the C. jejuni NCTC 11168 genome and, where possible, the RM1221 genome. Gene-specific primers were designed using the Primer Express 2.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and NetPrimer (http://www.premierbiosoft.com/netprimer/index.html/) facilities. All primers have a calculated melting temperature (Tm) of approximately 59.0°C and are listed in Table 1. The binary gene assay was tested on both the RotorGene 3000 (Corbett Robotics, Brisbane, Australia) and the ABI 7300 (Applied Biosystems) real-time PCR platforms. The RotorGene 3000 PCR setup was as previously described (43), except that the total number of cycles was reduced from 40 to 30 cycles. For the ABI 7300 apparatus, amplifications were carried out in 96-well plates containing 5 pmol each primer (Sigma-Proligo, Lismore, Australia), 1 μl gDNA, 1× SYBR green I MasterMix (Applied Biosystems), and distilled water to a total volume of 20 μl. Cycling conditions were 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 10 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and combined annealing and extension at 59°C for 30 s. No-template controls were included in each real-time run for each primer set. For both real-time PCR platforms, dissociation curves spanning 61°C to 95°C were generated following amplification to detect primer dimer interference in no-template controls (seen as a distinct peak at or below 75°C) and to confirm melting profiles of amplicons.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for detection of binary genes, mapA, and ceuE in C. jejuni and C. colia

| Gene | Primer name | Primer sequence (5′→3′) | Primer length (bp) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cj0629 | Cj0629-For | CAAAACAATTCGGCAACTTGG | 21 | 51 |

| Cj0629-Rev | ACTACCATTTTCGAGTTTTATACCAGC | 27 | ||

| Cj0265c | Cj0265c-For | AAGCGAAAATAACAGGGTTTTGC | 23 | 175 |

| Cj0265c-Rev | GCTTACCTTATCCCATTTGCCA | 22 | ||

| Cj0178 | Cj0178-For | GAGTGGTTTTGGGCGTGTTAATA | 23 | 102 |

| Cj0178-Rev | GTTCCCGTTTGTGAATGAAATCTAG | 25 | ||

| Cj0299 | Cj0299-For | GAAAAACTTGGGCGAGTAACGA | 22 | 51 |

| Cj0299-Rev | GAGAGAAAGTCTCCATAGCCCTTG | 24 | ||

| Cj1319 | Cj1319-For | CACTTTAAATATGCTCGAAGCAGCT | 25 | 80 |

| Cj1319-Rev | TGCCATAAACTTCGCTTGTTGAG | 23 | ||

| Cj1723c | Cj1723c-For | AAACCTCTGCAGTTGCGCC | 19 | 56 |

| Cj1723c-Rev | ATATTGCGGATATACAGGATACGAAGT | 27 | ||

| Cj0008 | Cj0008-For | TGGAAAGTAAAAGATGAAAGCAAGACA | 27 | 122 |

| Cj0008-Rev | GCATAAAAATCTTTATGGTTTGAGGTG | 27 | ||

| Cj0486 | Cj0486-For | ATTACTAAACAAGAAGAGGGTGCGA | 25 | 56 |

| Cj0486-Rev | GCTACCAATGCAGCCTGGAT | 20 | ||

| mapA | mapA-For | GCTAGAGGAATAGTTGTGCTTGACAA | 26 | 67 |

| mapA-Rev | TTACTCACATAAGGTGAATTTTGATCG | 27 | ||

| ceuE | ceuE-For | CAAGTACTGCAATAAAAACTAGCACTACG | 29 | 72 |

| ceuE-Rev | AGCTATCACCCTCATCACTCATACTAATAG | 30 |

All primers were designed with a Tm of 59.0°C ± 1.0°C.

mapA and ceuE.

To determine the status of each binary gene (present, absent, or intermediate) in the 154 OzFoodNet and 29 PAH isolates and to reduce well usage of a previously described seven-member SNP assay (43), a strategy to normalize the reactions to a standard gene was devised. Membrane-associated protein A (encoded by the 645-bp gene mapA) and a periplasmic enterochelin-binding protein (encoded by the 990-bp gene ceuE) have previously been described as genetic markers for differentiating C. jejuni and C. coli from other campylobacters (20, 49). Alignments of mapA and ceuE sequences from C. jejuni, Campylobacter lari, C. coli, and Campylobacter upsaliensis allowed species-specific primer design for C. jejuni and C. coli. Gene-specific primers for mapA and ceuE were designed with a Tm of 59.0°C. The mapA and ceuE primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Nucleotide sequencing.

Sequencing was performed on a subset of the OzFoodNet isolates to define cutoff values for present, absent, and intermediate genotypes of all eight binary genes (GenBank accession no. DQ983332 to DQ983360). Gene-specific sequencing primers (Table 2) were used for amplification and sequencing reactions and were designed to encompass the real-time PCR primer binding sites. MLST and flaA SVR sequencing were carried out as previously described (8, 30, 35), and alleles were assigned based on previous database submissions (http://pubmlst.org/campylobacter; http://hercules.medawar.ox.ac.uk/flaA/). Each sequencing mix contained 30 to 60 ng purified PCR product (QIAGEN) and 3.2 pmol of either forward or reverse primer, brought to a total volume of 12 μl with double-distilled water. Sequencing reaction mixtures were labeled using ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator 3.1 chemistry. Products were submitted to the Australian Genome Research Facility (University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia) for processing.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for amplification and sequencing of binary genesa

| Gene | Primer name | Primer sequence (5′→3′) | Primer length (bp) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cj0629 | Cj0629gene-For | AAGGTGCAGGAGTAAATATATCTCAAGG | 28 | 440 |

| Cj0629gene-Rev | AGCATTAGAACGGATAGATCCTGTG | 25 | ||

| Cj0265c | Cj0265gene-For | TCTTTTGTTGTCCTAGCGACATGT | 24 | 471 |

| Cj0265gene-Rev | CATAGAACGGAAAATTGCAGGC | 22 | ||

| Cj0178 | Cj0178gene-For | GCAACAAGCACAAGAGAGGGTATAG | 25 | 487 |

| Cj0178gene-Rev | CCACATATCCATTATTTTCAAGTTCAGT | 28 | ||

| Cj0299 | Cj0299gene-For | AATTGGTTTAAAGAGTATAATACAAGCGG | 29 | 481 |

| Cj0299gene-Rev | TCATTTCCTTAACACTATTCATTGCTTC | 28 | ||

| Cj1319 | Cj1319gene-For | TCGCTATCCCCTACTCCTACACA | 23 | 489 |

| Cj1319gene-Rev | TGGAGTATTCCACTCCTGAGCCT | 23 | ||

| Cj1723c | Cj1723gene-For | AAATTTATCCCTGTCATTTTAGCATGT | 27 | 201 |

| Cj1723gene-Rev | TGGATAGAGATTTTGAATTTGACTGG | 26 | ||

| Cj0008 | Cj0008gene-For | TGGCAGGATTTCAATCACCAA | 21 | 549 |

| Cj0008gene-Rev | AATACTGACACTTAAACCATTTTTGCTG | 28 | ||

| Cj0486 | Cj0486gene-For | AATGCGAGTTTTAGAATCAATGCTG | 25 | 482 |

| Cj0486gene-Rev | GGAGTAGAAACAATGCGCCCTA | 22 |

All primers were designed with a Tm of 59.0°C ± 1°C.

RESULTS

Binary gene selection.

“Minimum SNPs” was applied to the combined CGH data of 20 strains from diverse sources to identify a set of gene targets that provided maximal discrimination of these isolates. Only CGH genes classed as absent or highly divergent (HD) in one or more isolates were included in the “Minimum SNPs” analysis, with moderately divergent genes as designated by Taboada and coworkers (51) excluded. Selection of genes with highly negative log ratios minimizes inter- and intra-array variance and likely represents the loss or acquisition of an entire gene (50). Data from a meta-analysis CGH study of 97 C. jejuni strains (including data from references 25, 41, and 42) were used to assess appropriate cutoff values for the 277 genes identified as exhibiting binary variability in the 20 strains (51). Only those genes that were (i) divergent in more than one strain and (ii) considered HD or absent, based on a log ratio (tester signal/C. jejuni NCTC 11168 signal) of ≤3.3 for any strains in the data set (51), were assessed further. By these criteria, 87 HD or absent genes were included in the analysis.

Following reduction of the data set to 87 genes, the CGH data for all 20 strains were converted to a “pseudosequence alignment” format to facilitate analysis by “Minimum SNPs.” Nonhybridizing genes (i.e., absent or HD) were coded as “A” and hybridizing genes coded as “T.” Where the CGH data called a gene as present in a given isolate, this gene was converted to a “T.” The resulting binary gene profiles of all 20 strains were subsequently analyzed using the D function of “Minimum SNPs.” Of the 87 HD and absent genes analyzed, eight targets were identified by “Minimum SNPs” that completely resolved the 20 strains. The binary targets, with their respective cumulative resolution (D) and function, are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Binary genes identified in this study

| Gene | Cumulative D | Presence in RM1221 | Function | Qualifiersa | Locationb | Gene length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cj0629 | 0.491 | No | Possible lipoprotein | 588367-591303 | PR8 | 2,937 |

| Cj0265c | 0.766 | No | Putative cytochrome c-type heme-binding periplasmic protein | 244448-245023 | NAc | 576 |

| Cj0178 | 0.889 | Yes | Putative outer membrane siderophore receptor | 173764-176031 | PR3 | 2,268 |

| Cj0299 | 0.947 | Yes | Putative periplasmic beta-lactamase | 273321-274094 | PR4 (PR1) | 774 |

| Cj1319 | 0.971 | Yes | Putative nucleotide sugar dehydratase | 1248624-1249595 | PR12 (PR5) | 972 |

| Cj1723c | 0.988 | No | Putative periplasmic protein | 1633895-1634119 | PR16 (PR7) | 225 |

| Cj0008 | 0.994 | No | Hypothetical protein | 12644-14395 | NA | 1,752 |

| Cj0486 | 1.0 | Yes | Putative sugar transporter | 453119-454375 | PR6 (PR2) | 1,257 |

| mapA | Yesd | Outer membrane lipoprotein | 960835-961479 | NA | 645 | |

| ceuE | Yese | Periplasmic enterochelin-binding protein | 1286672-1287664 | NA | 990 |

Of the eight binary genes, six were located within previously identified PRs. This was not surprising, as the PRs contain approximately half of the binary genes identified in C. jejuni (41). Four of the eight binary genes are absent in RM1221.

Real-time PCR interrogation of binary genes.

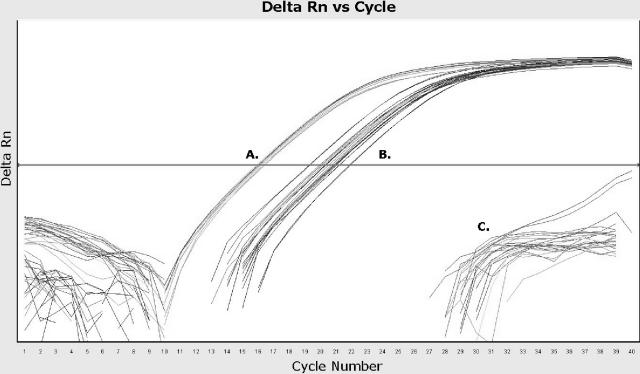

Real-time PCR allows direct quantitative comparison of PCR amplifications in different templates when normalized to a ubiquitous gene, such as 16S rRNA and recA in bacteria (48) or 18S rRNA and β-actin in human tissues (36). In the current study, binary gene status cutoff values were determined by normalization of the binary gene cycle threshold (CT) with the corresponding mapA/ceuE CT of the gDNA preparation. Cutoff values for gene presence were determined using (i) sequence data and (ii) the CT of C. jejuni NCTC 11168, which was used as a positive control in the binary gene assays. Genes were called as absent when the ΔCT (difference in CT) between the binary gene and mapA/ceuE CT values exceeded 10 cycles. The binary gene was designated as “intermediate” if the ΔCT relative to mapA/ceuE consistently fell between 3 and 10 cycles. Gene presence was ≤2 cycles of mapA/ceuE. These criteria were applicable using both the ABI 7300 and RG3000 apparatuses (Fig. 1). Of the eight binary targets, only Cj0629 was found to exhibit an “intermediate” genotype. DNA sequencing revealed that the intermediary genotype of Cj0629 was conferred by several 5′ polymorphisms at the Cj0629-Rev primer binding site, at positions −16, −22, −23, −24, and −25. In some isolates, the Cj0629-Rev mismatches were coupled with another polymorphism 8 bp upstream in Cj0629-For.

FIG. 1.

Real-time PCR amplification plot of the C. jejuni/C. coli binary gene assay using an ABI 7300 apparatus. The horizontal line on the plot indicates the threshold. The mapA or ceuE gene indicates whether the isolate is C. jejuni or C. coli, respectively, and is used to quantitate the binary gene assay. The ΔCT between mapA/ceuE and the binary gene is used to quantitatively determine whether the gene is present, absent, or intermediate within a given isolate. (A) mapA/ceuE and binary gene presence; (B) intermediate binary genotype; (C) binary gene absence and no-template control. Gene presence (binary gene CT minus mapA/ceuE CT), ΔCT ≤ 2; gene absence, ΔCT > 10; intermediate, ΔCT between 3 and 10.

The results of the binary gene typing on 181 out of the 183 isolates are displayed in Table 4. Two PAH isolates were negative for ceuE and mapA and gave uninterpretable results in the high-D SNP assay. Reextraction of gDNA from these isolates yielded a similar result. To confirm the quality of the DNA extractions, 01M28590 and 03M90835 were subjected to a thermophilic Campylobacter 23S rRNA gene PCR assay targeting C. jejuni, C. coli, C. lari, and C. upsaliensis (13). Both isolates were positive for the Therm PCR, indicating that the gDNA extraction was successful. As 01M28590 and 03M90835 are not C. jejuni or C. coli, these isolates were not examined further.

TABLE 4.

Distribution of eight binary genes in 181 C. jejuni and C. coli isolatesa

| Isolate set and STb | No. of isolates | flaA SVR(s) | Species | Clonal complex | Cj0629 | Cj0265c | Cj0178 | Cj0299 | Cj1319 | Cj1723 | Cj0008 | Cj0486 | BT | BT with Cj0486 removed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OzFoodNet isolates | ||||||||||||||

| 5 | 3 | 11 | C. jejuni | ST 353 | I | A | P | A | P | A | A | A | 1 | 1 |

| 527 | 2 | 11 | C. jejuni | ST 353 | I | A | P | A | P | A | A | A | 1 | 1 |

| 21 | 2 | 8 | C. jejuni | ST 21 | P | A | P | P | P | P | P | P | 8 | 8 |

| 53 | 1 | 1 | C. jejuni | ST 21 | I | A | P | P | P | P | P | P | 3 | 3 |

| 190 | 1 | 1 | C. jejuni | ST 21 | A | P | P | P | P | A | P | P | 13 | 13 |

| 569 | 1 | 1 | C. jejuni | ST 21 | A | P | P | P | P | A | P | P | 13 | 13 |

| 43c | 1 | 9 | C. jejuni | ST 21 | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | 9 | 9 |

| 25 | 2 | 1 | C. jejuni | ST 45 | A | A | A | A | P | A | A | A | 17 | 17 |

| 45 | 1 | 5 | C. jejuni | ST 45 | A | P | A | P | P | A | A | A | 19 | 19 |

| 529 | 1 | 9 | C. jejuni | ST 45 | A | A | A | P | A | A | A | A | 11 | 11 |

| 1616d | 1 | 156 | C. jejuni | ST 403 | A | P | A | A | P | A | A | A | 20 | 20 |

| 42 | 2 | 1, 9 | C. jejuni | ST 42 | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | 24 | 24 |

| 42 | 2 | 9 | C. jejuni | ST 42 | A | A | A | P | A | A | A | A | 11 | 11 |

| 48 | 3 | 1 | C. jejuni | ST 48 | A | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | 22 | 22 |

| 48 | 11 | 1 | C. jejuni | ST 48 | I | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | 7 | 7 |

| 48 | 9 | 1 | C. jejuni | ST 48 | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | 10 | 10 |

| 50 | 4 | 1, 350 | C. jejuni | ST 21 | P | P | P | P | P | A | A | P | 21 | 21 |

| 50 | 3 | 8, 10 | C. jejuni | ST 21 | P | P | P | P | P | P | A | P | 25 | 25 |

| 451 | 2 | 1 | C. jejuni | ST 21 | A | P | P | P | P | A | P | P | 13 | 13 |

| 536 | 1 | 10 | C. jejuni | ST 21 | P | A | P | P | P | A | A | P | 14 | 14 |

| 51 | 1 | 2 | C. jejuni | ST 443 | A | A | P | P | P | A | A | P | 16 | 16 |

| 52 | 5 | 4 | C. jejuni | ST 52 | P | A | P | P | P | A | A | P | 14 | 14 |

| 161 | 4 | 2, 4, 10 | C. jejuni | ST 52 | A | A | P | P | P | A | A | P | 16 | 16 |

| 70 | 1 | 4 | C. jejuni | ST 52 | P | A | P | P | P | A | A | P | 14 | 14 |

| 61 | 1 | 14 | C. jejuni | ST 61 | A | A | A | P | A | A | A | A | 11 | 11 |

| 227 | 4 | 1, 10 | C. jejuni | ST 206 | P | P | P | P | P | A | P | P | 26 | 26 |

| 227 | 1 | 1 | C. jejuni | ST 206 | P | P | P | P | P | A | A | P | 21 | 21 |

| 233 | 1 | 1 | C. jejuni | ST 45 | A | P | A | A | P | A | A | A | 20 | 20 |

| 197 | 1 | 12 | C. jejuni | ST 257 | I | P | P | P | A | A | P | P | 4 | 4 |

| 197 | 1 | 12 | C. jejuni | ST 257 | A | A | P | P | A | A | A | P | 15 | 15 |

| 257 | 17 | 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 20 | C. jejuni | ST 257 | A | A | P | P | A | A | A | P | 15 | 15 |

| 532 | 2 | 12 | C. jejuni | ST 257 | A | A | P | P | A | A | A | P | 15 | 15 |

| 312 | 1 | 1 | C. jejuni | ST 658 | A | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | 34 | 22 |

| 354 | 3 | 18, 20, 37 | C. jejuni | ST 354 | A | A | P | P | P | A | A | P | 16 | 16 |

| 528 | 18 | 1, 20 | C. jejuni | ST 354 | A | A | P | P | P | A | A | P | 16 | 16 |

| 533 | 1 | 1 | C. jejuni | ST 52 | I | A | P | A | P | A | A | A | 1 | 1 |

| 449 | 2 | 14, 33 | C. jejuni | ST 61 | A | A | P | P | P | A | A | A | 18 | 16 |

| 531 | 9 | 1, 2, 5, 20 | C. jejuni | NA | A | A | P | P | P | A | A | A | 18 | 16 |

| 531 | 1 | 20 | C. jejuni | NA | A | P | P | P | P | A | A | A | 23 | 23 |

| 523 | 3 | 1, 71, 90 | C. jejuni | ST 658 | I | P | A | P | A | A | P | P | 27 | 27 |

| 523 | 1 | 1 | C. jejuni | ST 658 | I | P | A | A | A | A | A | P | 28 | 28 |

| 523 | 1 | 2 | C. jejuni | ST 658 | I | P | P | P | A | A | P | P | 4 | 4 |

| 523 | 1 | 11 | C. jejuni | ST 658 | I | P | P | P | P | A | A | P | 5 | 5 |

| 523 | 1 | 71 | C. jejuni | ST 658 | I | P | P | P | A | A | A | P | 6 | 6 |

| 524 | 2 | 10 | C. jejuni | ST 353 | P | A | P | A | P | A | A | A | 30 | 30 |

| 525 | 6 | 2 | C. jejuni | ST 607 | A | A | P | A | P | A | A | A | 31 | 31 |

| 526 | 1 | 3 | C. jejuni | NA | A | A | A | A | P | A | A | A | 17 | 17 |

| 530 | 2 | 8 | C. jejuni | NA | A | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | 32 | 32 |

| 530 | 1 | 8 | C. jejuni | NA | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | 33 | 10 |

| 530 | 4 | 8 | C. jejuni | NA | A | A | P | P | P | A | P | A | 34 | 22 |

| 535 | 1 | 4 | C. jejuni | ST 460 | A | A | A | A | P | A | A | P | 29 | 17 |

| 537 | 1 | 11 | C. jejuni | ST 353 | I | A | P | A | P | A | A | P | 2 | 1 |

| 538 | 1 | 12 | C. jejuni | ST 45 | A | A | A | P | A | A | A | A | 11 | 11 |

| 567 | 1 | 9 | C. jejuni | ST 22 | A | A | P | P | A | A | A | A | 12 | 15 |

| 555 | 1 | 16 | C. coli | NA | A | A | P | P | A | A | A | A | 12 | 15 |

| 555 | 1 | 16 | C. coli | NA | A | A | A | P | A | A | A | A | 11 | 11 |

| PAH isolates | ||||||||||||||

| ND | 3 | 17, 30 | C. coli | ND | A | A | A | P | P | A | A | P | 36 | 35 |

| ND | 1 | 16 | C. coli | ND | A | A | A | A | P | A | A | A | 17 | 17 |

| ND | 1 | 467 | C. coli | ND | A | A | A | P | P | A | A | A | 35 | 35 |

| ND | 3 | 16 | C. jejuni | ND | A | A | P | P | A | A | A | P | 15 | 15 |

| ND | 8 | 36 | C. jejuni | ND | A | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | 22 | 22 |

| ND | 1 | 36 | C. jejuni | ND | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | 10 | 10 |

| ND | 2 | 36 | C. jejuni | ND | I | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | 7 | 7 |

| ND | 1 | 222 | C. jejuni | ND | A | A | P | P | P | A | A | A | 18 | 16 |

| ND | 2 | 57 | C. jejuni | ND | P | A | P | P | P | A | A | P | 14 | 14 |

| ND | 1 | 18 | C. jejuni | ND | A | A | P | P | P | A | A | P | 16 | 16 |

| 227 | 1 | 9 | C. jejuni | ST 206 | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | 10 | 10 |

| ND | 1 | 9 | C. jejuni | ND | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | 10 | 10 |

| ND | 1 | 9 | C. jejuni | ND | P | A | P | P | P | A | A | P | 14 | 14 |

| 583 | 1 | 239 | C. jejuni | ST 45 | A | A | A | P | A | A | A | A | 11 | 11 |

Abbreviations: ND, not determined; NA, not applicable; I, intermediate genotype; A, absent genotype; P, present genotype.

Isolates are grouped according to their corresponding seven-member SNP profile (43).

Genome-sequenced strain, NCTC 11168.

NCTC 11351; used in CGH array study by Pearson et al. (41). The ST identity of this isolate was identified as part of this study.

As controls for the binary gene assay, two type cultures (NCTC 11351 and NCTC 11168) were tested at the eight binary genes. The NCTC 111351 isolate has been characterized by CGH (41), and NCTC 11168 has been used to construct and interrogate C. jejuni arrays (3, 11, 25, 26, 41, 42, 51). As expected, the NCTC 11168 strain was shown to possess all eight binary genes by the use of both real-time PCR platforms (Table 4). However, the CGH data and binary gene profiles of NCTC 11351 differed at seven of the eight markers, a result consistent between real-time PCR apparatuses. Although the exact reason for the incongruity could not be determined, MLST of NCTC 11351 confirmed that its genotype was nearly identical to a previous submission of this strain (http://pubmlst.org/campylobacter/).

The eighth binary gene, Cj0486, was the only gene that failed to resolve different strains of the same sequence type (ST). This was an unexpected finding, as Cj0486 is not in close proximity to any MLST locus and resides within PR6 (51). Additionally, RM1221 contains the insertion of a prophage element 3.6 kb downstream of PR6 (15), suggesting that this region is not genetically uniform between strains. It was investigated whether Cj0486 was redundant to the binary gene assay and could be removed from the data set. When Cj0486 was omitted from the OzFoodNet isolate profiles, binary types (BTs) 1 and 2, 17 and 29, 22 and 34, 10 and 33, 16 and 18, and 12 and 15 became indistinguishable from each other (Table 4). Although this removal did not decrease the ability to resolve unrelated isolates (i.e., the BTs still separated unrelated STs coupled with SNP groups), the resolution (D) of the binary typing method decreased from 0.934 to 0.897. It was concluded that a set of eight binary markers was identified that provides resolving power complementary to MLST and MLST-derived SNPs.

Performance of the binary markers with a larger CGH data set.

Subsequent to development of the eight-member binary gene assay, Champion et al. (3) conducted a large CGH study examining 111 diverse C. jejuni strains from environmental, animal, and clinical sources. The performance of the eight binary genes identified in the current investigation was assessed by combining the CGH data for the 20 strains with the larger data set of Champion et al. (3). Binary gene data were obtained for the 111 strains from http://bugs.sgul.ac.uk/bugsbase/tabs/experiment.php (experiment accession: E-BUGS-22) and were assembled into the nucleotide format readable by “Minimum SNPs” as described in Materials and Methods. Four strains, 38857, 40209, 55703, and 59161, were removed from further analysis as they hybridized to all 1,654 NCTC 11168-derived open reading frames and were thus not able to be discriminated from each other or from NCTC 11168. In total, 127 strains were reexamined: 107 from the work of Champion et al. (3), 18 from the work of Pearson et al. (41), one from the work of Poly et al. (42), and RM1221 (15). Of the 696 genes that were binary within the 127-strain data set, 141 genes were found in a single isolate, and a further 149 genes have been classed as moderately divergent by Taboada et al. (51).

Taking these parameters into account, 406 genes were considered HD in the collection of 127 strains and were included for analysis using “Minimum SNPs.” With unconstrained parameters, the first binary gene set identified by “Minimum SNPs” required only 12 targets to reach a D of 0.9975, and the targets identified are Cj0628 (0.5039), Cj0755 (0.7552), Cj1520 (0.8745), Cj0265c (0.9336), Cj0032 (0.9643), Cj1339c (0.9798), Cj0295 (0.9879), Cj0008 (0.9918), Cj1051c (0.9946), Cj0033 (0.9958), Cj0056c (0.9968), and Cj0618 (0.9975). The resolving power of the original binary gene set was recalculated using the larger CGH data set: Cj0629 (0.4927), Cj0265c (0.7377), Cj0178 (0.8161), Cj0299 (0.8448), Cj1319 (0.8761), Cj1723c (0.9198), Cj0008 (0.9528), Cj0486 (0.956), Cj1520 (0.9783), Cj0755 (0.9875), Cj0151c (0.9926), Cj0032 (0.9954), Cj1133 (0.9968), and Cj0416 (0.9975). It can be seen that two more targets were required to reach a D of 0.9975. Interestingly, six markers were shared between the two sets. These results indicate that effective sets of binary markers can be derived from small data sets and that these sets of markers can be progressively improved as additional data become available.

Reanalysis of SNP typing procedure.

The utility of SNPs as an alternative to full MLST characterization of C. jejuni and C. coli has previously been detailed (1, 2, 43). In the study by Price et al. (43), SNPs were interrogated by AS real-time PCR combined with SYBR green I detection. The AS real-time PCR method coupled with SYBR green I chemistry provides a flexible, generic, and cost-effective means of genotyping SNPs, in comparison to labeled primer or probe methodologies (27, 32).

One substantial drawback of the AS real-time PCR procedure is that multiplexing is not feasible, as each AS reaction must be performed separately. Previous researchers (17, 38) have described a method of multiplexing SYBR green I AS real-time reactions by incorporation of GC-rich sequence onto the 5′ end of one AS primer. The addition of a GC clamp to one primer facilitates Tm discrimination of the resultant amplicons. However, incorporating two AS primers targeting the same SNP into a single tube substantially increases the frequency of misprimed PCR products (18), which subsequently amplify exponentially, potentially proving problematic for endpoint analyses such as Tm differentiation. To circumvent issues with mispriming, we investigated an AS real-time PCR method using SYBR green I that did not rely on multiplexing of primers but which reduced the well usage in a fashion similar to that of the GC clamp.

The method involved normalizing the AS reactions for seven SNPs, aspA174, gly267, glnA369, gltA12, uncA189, pgm348, and tkt297 (43), with the mapA or ceuE CT of C. jejuni or C. coli, respectively. A similar strategy has been reported by Huygens et al. (23). Because of the high reproducibility of the AS method, it is superfluous to include all AS reactions for polymorphism determination. Using mapA/ceuE as a “universal control,” the difference in cycles (ΔCT) between the mapA/ceuE and the AS reactions could be quantitated, allowing polymorphisms to be determined without the need for performing all AS reactions.

Criteria for the reduced SNP interrogation method by normalization to mapA/ceuE are shown in Table 5. Using the normalization method, the number of reactions required to interrogate the seven-member C. jejuni/C. coli high-D SNP assay decreased from 15 to 9. The two-state polymorphisms at glyA267, pgm348, and tkt297 could be reduced to a single reaction, without affecting polymorphism determination. Similarly, for the three-state SNP aspA174, only two of the three polymorphisms require interrogation to confidently determine all polymorphisms. Using glyA267 as an example, if only the AS primer glyA267-G is tested, and the difference between the AS G reaction and the mapA/ceuE CT is ≤8, the polymorphism present is A. However, if the difference between the mapA/ceuE CT and the G reaction is ≥2, the G polymorphism is present in the sample. The criteria are mutually exclusive, thus removing any ambiguity in calling polymorphisms. By using the parameters for aspA174, glyA267, pgm348, and tkt297, all polymorphic variants were unambiguously determined.

TABLE 5.

Parameters for reduction of well usage in seven high-D C. jejuni/C. coli SNPs

| High-D SNP | Reaction(s) required to determine polymorphism | Parameter (mapA CT − AS reaction CT) |

|---|---|---|

| aspA174 A/G/T | G+T | A: ≥7 at G; ≥13 at T |

| G: ≤1 at G; ≥9 at T | ||

| T: ≥9 at G; ≤0 at T | ||

| glyA267 A/G | G only | A: ≥9 at G |

| G: ≤4 at G | ||

| glnA369 C/T | T only | C: ≥13 at T |

| T1: ≤11 but ≥6 at T | ||

| T2: ≤2 at T | ||

| gltA12 A/G | A+Ga | |

| uncA189 C/T | C only | C: ≤2 at C |

| T1: ≤9 but ≥4 at C | ||

| T2: ≥12 at C | ||

| pgm348 A/G | A only | A: ≤0 at A |

| G: ≥2 at A | ||

| tkt297 C/T | T only | C: ≥11 at T |

| T: ≤5 at T |

Both reactions were required in order to call the genotype.

uncA189, glnA369, and gltA12 differ from glyA267, pgm348, and tkt297 in that there are ΔCT variations within a single polymorphism, allowing subdivision of polymorphisms into two allelic states (43). For uncA189, use of the uncA189-C primer in conjunction with mapA/ceuE permitted discrimination between the two T allelic states (T1 and T2), as well as efficiently called the matched C polymorphism. Similarly, the glnA369-T primer was capable of discriminating C, T1, and T2 polymorphic states at glnA369. At the gltA12 SNP, the A polymorphism could be further subdivided depending on whether it originated from C. jejuni (A1) or C. coli (A2). However, isolate NCTC 11351 did not fall into the assigned cutoffs for single reaction interrogation of gltA12, despite readily calling the G polymorphism when both the gltA12-A and gltA12-G reactions were performed. To resolve this anomaly, the ST of NCTC 11351 was determined. This revealed that NCTC 11351 shares six out of seven loci with ST 403, except at the gltA locus, where it contains a unique allele harboring a single mismatch at position 13 of gltA, directly adjacent to the gltA12 SNP. The new allele (gltA156) and ST (ST 1616) for NCTC 11351 were deposited into the MLST database. MLST was also undertaken on two PAH isolates to confirm the fidelity of the refined SNP interrogation assay (Table 4).

Resolving powers of the different typing methods.

Of the 181 C. jejuni and C. coli isolates used in the current investigation, 154 have previously been genotyped by MLST, flaA SVR sequencing, and SNP typing (37, 43). Within these 154 isolates, 84 have also been characterized by PFGE (37). The extensive data generated for these isolates facilitated performance comparisons of binary gene typing both independently and in conjunction with the other genotyping methods. In addition, single and combinatorial methods could be directly compared to PFGE.

As expected, PFGE was the most discriminatory independent method, resolving the greatest number of genotypes (n = 53) within the 84 isolates. MLST generated 32 genotypes corresponding to a D of 0.957 (37). SNP typing yielded fewer genotypes than MLST (n = 20), and flaA SVR alone provided the lowest resolution and the fewest genotypes of the three methods (43). Comparison of binary gene data generated in the current study identified 27 genotypes and a D of 0.950 in the 84 isolates, lower than those obtained with PFGE and MLST but higher than those obtained with SNP typing or flaA SVR (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Comparative resolution of genotyping methods for C. jejuni

| Typing method(s) | Value with isolate group:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 84 isolatesa

|

154 isolatesb

|

PAH isolates

|

||||

| No. of genotypes | D | No. of genotypes | D | No. of genotypes | D | |

| Binary | 27 | 0.950 | 33 | 0.934 | 11 | 0.883 |

| MLST | 32 | 0.957 | 40 | 0.94 | ||

| flaA SVR | 15 | 0.877 | 19 | 0.858 | 10 | 0.812 |

| SNPs | 20 | 0.935 | 24 | 0.919 | 9 | 0.801 |

| PFGE | 53 | 0.972 | ||||

| SNPs and binary | 37 | 0.963 | 47 | 0.947 | 13 | 0.895 |

| SNPs and flaA SVR | 39 | 0.963 | 53 | 0.952 | 12 | 0.826 |

| Binary and flaA SVR | 45 | 0.976 | 64 | 0.969 | 14 | 0.900 |

| MLST and binary | 41 | 0.973 | 55 | 0.958 | ||

| MLST and flaA SVR | 45 | 0.969 | 63 | 0.959 | ||

| SNPs, binary, and flaA SVR | 47 | 0.978 | 69 | 0.970 | 14 | 0.900 |

| MLST, binary, and flaA SVR | 51 | 0.981 | 75 | 0.975 | ||

The combinatorial power of the genotyping methods was also compared to PFGE. MLST in combination with the binary genes provided resolution comparable to that of PFGE and higher than that of MLST-flaA SVR in the collection of 84 isolates, despite resolving fewer genotypes. The SNP-binary assay equalled SNP-flaA SVR in discriminating the 84 isolates, a trend very similar in the larger collection of 154 isolates. Binary-flaA SVR was the most discriminatory of the double genotyping methods and outperformed MLST-flaA SVR in both collections of isolates. By utilizing any two genotyping methods in combination, a degree of resolution similar to that of PFGE within the 84 isolates is obtained. When three methods are used in combination (SNP-binary-flaA SVR or MLST-binary-flaA SVR), the degree of resolution surpasses that of PFGE (Table 6).

It has previously been demonstrated that SNP typing can resolve isolates unrelated by MLST when used in combination with flaA SVR sequencing (43). Of the 154 isolates, SNP-flaA SVR was unable to resolve only two unrelated STs, STs 533 and 528. In all other cases, unrelated STs sharing SNP profiles could be differentiated when flaA SVR was included as an additional locus. It was investigated whether the binary gene assay could replace flaA SVR when used in combination with SNP typing. The binary genes performed comparably to flaA SVR in differentiating between unrelated isolates sharing the same SNP profile and yielded a D comparable to that for SNP-flaA SVR (Table 4). Similarly to SNP-flaA SVR, a single circumstance arose (STs 449 and 531) in which unrelated isolates were unable to be differentiated with the SNP-binary gene approach, with the remaining unrelated isolates resolved following the addition of the eight binary genes. The binary gene markers efficiently provide typing resolution that is complementary to the SNP-based genotyping and can be conveniently interrogated on the same platforms as the SNPs.

DISCUSSION

This investigation describes the development and refinement of rapid real-time PCR-based genotyping assays for the food-borne pathogens C. jejuni and C. coli. Polymorphic targets were identified using a systematic computerized approach that enabled the selection of a small, resolution-optimized set of binary targets from CGH data. We have previously described the derivation of high-resolution SNP sets from MLST databases of C. jejuni/C. coli, S. aureus, and N. meningitidis (43, 44). Using “Minimum SNPs,” seven high-D SNPs were identified from the C. jejuni/C. coli MLST database that in combination provide a D of 0.98 relative to the MLST database. While the SNP typing method was unable to resolve some isolates belonging to different MLST complexes, the addition of the flaA SVR locus to the seven-member SNP profile enabled resolution comparable to that of MLST-flaA SVR and clustered isolates in a similar fashion (43).

The advantage of the SNP/flaA SVR approach over MLST/flaA SVR is the substantial reduction of DNA sequencing performed. However, flaA SVR remains sequence based and is therefore not adaptable to real-time PCR or low-density array platforms. In contrast, the binary gene interrogation is inherently simple and can be performed on the same platform as SNP interrogation. A major rationale for this study was to determine whether the binary gene assay could replace flaA SVR when used in combination with SNP typing or MLST. It has been shown that the binary genes are appropriate for this purpose. As the binary targets were efficient at adding resolving power to the MLST and SNP profiles, it can be speculated that these markers represent regions of the genome that undergo rapid evolution, similarly to flaA SVR. However, the specific mechanisms driving this apparent selective pressure remain to be elucidated.

A very recent C. jejuni CGH study (3) used a phylogenomics approach to reveal genetic markers characteristic of isolates from different sources. Two clusters of genetically distinct isolates were identified; one cluster, termed the “livestock” clade, was associated predominantly with poultry, cattle, and sheep, whereas the “nonlivestock” clade comprised isolates primarily from environmental sources. Human campylobacteriosis isolates were distributed between the clades in approximately equal numbers, suggesting transmission to humans from both nonlivestock and livestock origins. The CGH data, in conjunction with phylogenetic analysis, identified a genetic island from Cj1321 to Cj1326 within the O-linked flagellin glycosylation locus whose presence was strongly correlated with the livestock clade but which was predominantly absent in the nonlivestock clade (3). Investigations that are focused on Campylobacter transmission from chicken or livestock sources could be readily tailored to include one or more binary genes from the Cj1321-to-Cj1326 flagellin glycosylation locus in the current binary gene assay. An advantage of the computerized approach adopted in this investigation is the ability to directly select particular polymorphic targets of interest or to exclude unsuitable targets according to the requirements of the end user. As an example of this utility of “Minimum SNPs,” the Cj0486 gene, which completely correlated with ST identity in the OzFoodNet isolate collection in the current study, may be readily replaced by one of the genes residing in the Cj1321-to-Cj1326 genetic island and the resolution of the new binary gene set assessed. Alternatively, one or more of the genes in the flagellin glycosylation locus may be added to the existing eight-target binary gene assay, or the “include” function of “Minimum SNPs” (43) could be applied to derive a new resolution-optimized set of binary markers that includes the Cj1321-to-Cj1326 locus.

A comparison was made between the original eight binary genes identified using 20 strains (15, 41, 42) and 127 strains, which included the 107 strains from the work of Champion et al. (3). The performance of the eight-binary gene set was compared with that of an unconstrained binary gene set generated from the 127 strains. Unsurprisingly, the original eight binary markers were not as discriminatory when the extra 107 strains were incorporated into the data set, yielding a D of 0.956 versus a D of 0.9918 for an unconstrained eight-member gene set. However, when “Minimum SNPs” was used to determine resolution of the 127 strains using either (i) the eight binary markers identified in this study or (ii) unconstrained parameters, only two additional binary markers were required to achieve the same resolution between the two pathways. Six of the binary markers were common to both data sets. This finding suggests that the original binary gene set identified from comparative genomics of 20 strains is powerful in resolving much larger data sets. In support of this, 181 isolates were empirically tested at the eight binary genes, and high-resolution fingerprints within and between clonal complexes were observed.

The resolving powers of the genotyping methods for 84 isolates (37) were compared. While the SNP/binary assay performed well against SNP/flaA SVR, it was unable to reach the resolution obtained with PFGE. Other real-time PCR-based methods, such as high-resolution melting temperature analysis of hypervariable genetic loci, may be useful additions to the SNP/binary gene assay to augment their resolving power. We are currently developing Tm-based assays targeting the “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat” region of C. jejuni (24) suitable for this purpose. In addition, assessing the performance of the SNP and binary gene typing methods with outbreak isolates will provide valuable information on the utility of these methods for tracing and epidemiology.

In addition to the binary gene assay, we have refined a seven-member SNP typing method for C. jejuni and C. coli that enables well usage comparable to that of the multiplex TaqMan or molecular beacon systems. The benefits of the refined SNP typing assay are its flexibility and cost. Using the generic SYBR green I dye allows a simple and cost-effective setup in comparison to the multiplexed fluorescent resonance energy transfer-based systems. By normalizing the SNP assay to mapA/ceuE, each polymorphism at the seven SNPs can be unambiguously determined and the number of reactions can be reduced from 15 to 9. Only one SNP, gltA12, required both reactions to determine whether the A or G polymorphism was present in the gDNA, due to a penultimate mismatch between the gltA12-A primer and the NCTC 11351 template.

We have shown that the eight-member binary gene assay, in concert with the refined SNP typing assay, can provide high-resolution bacterial fingerprints of C. jejuni and C. coli comparable to those for MLST-flaA SVR or SNP-flaA SVR by using a unified real-time PCR approach. Further advantages of this combinatorial method over sequence-based methods such as MLST and flaA SVR include its simplicity, flexibility, robustness, cost-effectiveness, short turnaround time, and high-throughput potential. This approach to the derivation of resolution-optimized sets of binary markers from CGH is straightforward, novel, and applicable to any species for which such data are available.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Cooperative Research Centres program of the Australian Federal Government. E.P.P. is in receipt of a postgraduate studentship from the Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation, QUT.

We acknowledge the Campylobacter Subtyping Study Group and J. Schooneveldt for kindly providing the C. jejuni and C. coli isolates used in this study.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 September 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Best, E. L., A. J. Fox, J. A. Frost, and F. J. Bolton. 2004. Identification of Campylobacter jejuni multilocus sequence type ST-21 clonal complex by single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2836-2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Best, E. L., A. J. Fox, J. A. Frost, and F. J. Bolton. 2005. Real-time single-nucleotide polymorphism profiling using Taqman technology for rapid recognition of Campylobacter jejuni clonal complexes. J. Med. Microbiol. 54:919-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Champion, O. L., M. W. Gaunt, O. Gundogdu, A. Elmi, A. A. Witney, J. Hinds, N. Dorrell, and B. W. Wren. 2005. Comparative phylogenomics of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals genetic markers predictive of infection source. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:16043-16048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudhuri, R. R., and M. J. Pallen. 2006. xBASE, a collection of online databases for bacterial comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:D335-D337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark, C. G., L. Bryden, W. R. Cuff, P. L. Johnson, F. Jamieson, B. Ciebin, and G. Wang. 2005. Use of the Oxford multilocus sequence typing protocol and sequencing of the flagellin short variable region to characterize isolates from a large outbreak of waterborne Campylobacter sp. strains in Walkerton, Ontario, Canada. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2080-2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Boer, P., B. Duim, A. Rigter, J. van der Plas, W. F. Jacobs-Reitsma, and J. A. Wagenaar. 2000. Computer-assisted analysis and epidemiological value of genotyping methods for Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1940-1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dingle, K. E., F. M. Colles, D. Falush, and M. C. J. Maiden. 2005. Sequence typing and comparison of population biology of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:340-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dingle, K. E., F. M. Colles, D. R. A. Wareing, R. Ure, A. J. Fox, F. E. Bolton, H. J. Bootsma, R. J. L. Williams, R. Urwin, and M. C. J. Maiden. 2001. Multilocus sequence typing system for Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dingle, K. E., F. M. Colles, R. Ure, J. A. Wagenaar, B. Duim, F. J. Bolton, A. J. Fox, D. R. A. Wareing, and M. C. J. Maiden. 2002. Molecular characterization of Campylobacter jejuni clones: a basis for epidemiologic investigation. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:949-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dingle, K. E., N. Van Den Braak, F. M. Colles, L. J. Price, D. L. Woodward, F. G. Rodgers, H. P. Endtz, A. van Belkum, A., and M. C. J. Maiden. 2001. Sequence typing confirms that Campylobacter jejuni strains associated with Guillain-Barré and Miller-Fisher syndromes are of diverse genetic lineage, serotype, and flagella type. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3346-3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorrell, N., J. A. Mangan, K. G. Laing, J. Hinds, D. Linton, H. Al-Ghusein, B. G. Barrell, J. Parkhill, N. G. Stoker, A. V. Karlyshev, P. D. Butcher, and B. W. Wren. 2001. Whole genome comparison of Campylobacter jejuni human isolates using a low-cost microarray reveals extensive genetic diversity. Genome Res. 11:1706-1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duim, B., P. C. R. Godschalk, N. van den Braak, K. E. Dingle, J. R. Dijkstra, E. Leyde, J. van der Plas, F. M. Colles, H. P. Endtz, J. A. Wagenaar, M. C. J. Maiden, and A. van Belkum. 2003. Molecular evidence for dissemination of unique Campylobacter jejuni clones in Curaçao, Netherlands Antilles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5593-5597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eyers, M., S. Chapelle, G. Van Camp, H. Goossens, and R. De Wachter. 1993. Discrimination among thermophilic Campylobacter species by polymerase chain reaction amplification of 23S rRNA gene fragments. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:3340-3343. (Erratum, 32:1623, 1994.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzgerald, C., L. O. Helsel, M. A. Nicholson, S. J. Olsen, D. L. Swerdlow, R. Flahart, J. Sexton, and P. I. Fields. 2001. Evaluation of methods for subtyping Campylobacter jejuni during an outbreak involving a food handler. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2386-2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fouts, D. E., E. F. Mongodin, R. E. Mandrell, W. G. Miller, D. A. Rasko, J. Ravel, L. M. Brinkac, R. T. DeBoy, C. T. Parker, S. C. Daugherty, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, R. Madupu, S. A. Sullivan, J. U. Shetty, M. A. Ayodeji, A. Shvartsbeyn, M. C. Schatz, J. H. Badger, C. M. Fraser, and K. E. Nelson. 2005. Major structural differences and novel potential virulence mechanisms from the genomes of multiple Campylobacter species. PLoS Biol. 3:e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.French, N., M. Barrigas, P. Brown, P. Ribiero, N. Williams, H. Leatherbarrow, R. Birtles, E. Bolton, P. Fearnhead, and A. Fox. 2005. Spatial epidemiology and natural population structure of Campylobacter jejuni colonizing a farmland ecosystem. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1116-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Germer, S., and R. Higuchi. 1999. Single-tube genotyping without oligonucleotide probes. Genome Res. 9:72-78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giffard, P. M., J. A. McMahon, H. M. Gustafson, R. T. Barnard, and J. Voisey. 2001. Comparison of competitively primed and conventional allelic-specific nucleic acid amplification. Anal. Biochem. 292:207-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilpin, B., A. Cornelius, B. Robson, N. Boxall, A. Ferguson, C. Nicol, and T. Henderson. 2006. Application of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to identify potential outbreaks of campylobacteriosis in New Zealand. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:406-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez, I., K. A. Grant, P. T. Richardson, S. F. Park, and M. D. Collins. 1997. Species identification of the enteropathogens Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli by using a PCR test based on the ceuE gene encoding a putative virulence determinant. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:759-763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunter, P. R., and M. A. Gaston. 1988. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson's index of diversity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:2465-2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huygens, F., A. J. Stephens, G. R. Nimmo, and P. M. Giffard. 2004. mecA locus diversity in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates in Brisbane, Australia, and the development of a novel diagnostic procedure for the Western Samoan phage pattern clone. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1947-1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huygens, F., J. Inman-Bamber, G. R. Nimmo, W. Munckhof, J. Schooneveldt, B. Harrison, J. A. McMahon, and P. M. Giffard. 2006. Staphylococcus aureus genotyping using novel real-time PCR formats. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:3712-3719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jansen, R., J. D. Embden, W. Gaastra, and L. M. Schouls. 2002. Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1565-1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leonard, E. E., II, T. Takata, M. J. Blaser, S. Falkow, L. S. Tompkins, and E. C. Gaynor. 2003. Use of an open-reading frame-specific Campylobacter jejuni DNA microarray as a new genotyping tool for studying epidemiologically related isolates. J. Infect. Dis. 187:691-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leonard, E. E., II, L. S. Tompkins, S. Falkow, and I. Nachamkin. 2004. Comparison of Campylobacter jejuni isolates implicated in Guillain-Barré syndrome and strains that cause enteritis by a DNA microarray. Infect. Immun. 72:1199-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livak, K. J. 1999. Allelic discrimination using fluorogenic probes and the 5′ nuclease assay. Genet. Anal. 14:143-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowe, B., H. A. Avila, F. R. Bloom, M. Gleeson, and W. Kusser. 2003. Quantitation of gene expression in neural precursors by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction using self-quenched, fluorogenic primers. Anal. Biochem. 315:95-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manning, G., C. G. Dowson, M. C. Bagnall, I. H. Ahmed, M. West, and D. G. Newell. 2003. Multilocus sequence typing for comparison of veterinary and human isolates of Campylobacter jejuni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6370-6379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meinersmann, R. J., L. O. Helsel, P. I. Fields, and K. L. Hiett. 1997. Discrimination of Campylobacter jejuni isolates by fla gene sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2810-2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mellmann, A., J. Mosters, E. Bartelt, P. Roggentin, A. Ammon, A. W. Friedrich, H. Karch, and D. Harmsen. 2004. Sequence-based typing of flaB is a more stable screening tool than typing of flaA for monitoring of Campylobacter populations. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4840-4842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mhlanga, M. M., and L. Malmberg. 2001. Using molecular beacons to detect single-nucleotide polymorphisms with real-time PCR. Methods 25:463-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michaud, S., S. Ménard, and R. D. Arbeit. 2005. Role of real-time molecular typing in the surveillance of Campylobacter enteritis and comparison of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profiles from chicken and human isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1105-1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller, W. G., S. L. W. On, G. Wang, S. Fontanoz, A. J. Lastovica, and R. E. Mandrell. 2005. Extended multilocus sequence typing system for Campylobacter coli, C. lari, C. upsaliensis, and C. helveticus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2315-2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nachamkin, I., K. Bohachick, and C. M. Patton. 1993. Flagellin gene typing of Campylobacter jejuni by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:1531-1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nazarenko, I., B. Lowe, M. Darfler, P. Ikonomi, D. Schuster, and A. Rashtchian. 2002. Multiplex quantitative PCR using self-quenched primers labeled with a single fluorophore. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Reilly, L. C., T. J. J. Inglis, L. Unicomb, and the Australian Campylobacter Subtyping Study Group. 2006. Australian multicentre comparison of subtyping methods for the investigation of Campylobacter infection. Epidemiol. Infect. 134:768-779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Papp, A. C., J. K. Pinsonneault, G. Cooke, and W. Sadée. 2003. Single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping using allele-specific PCR and fluorescence melting curves. BioTechniques 34:1068-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parkhill, J., B. W. Wren, K. Mungall, J. M. Ketley, C. Churcher, D. Basham, T. Chillingworth, R. M. Davies, T. Feltwell, S. Holroyd, K. Jagels, A. V. Karlyshev, S. Moule, M. J. Pallen, C. W. Penn, M. A. Quail, M.-A. Rajandream, K. M. Rutherford, A. H. M. van Vliet, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrell. 2000. The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature 403:665-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patra, G., L. E. Williams, Y. Qi, S. Rose, R. Redkar, and V. G. Delvecchio. 2002. Rapid genotyping of Bacillus anthracis strains by real-time polymerase chain reaction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 969:106-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pearson, B. M., C. Pin, J. Wright, K. I'Anson, T. Humphrey, and J. M. Wells. 2003. Comparative genome analysis of Campylobacter jejuni using whole genome DNA microarrays. FEBS Lett. 554:224-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poly, F., D. Threadgill, and A. Stintzi. 2004. Identification of Campylobacter jejuni ATCC 43431-specific genes by whole microbial genome comparisons. J. Bacteriol. 186:4781-4795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Price, E. P., V. Thiruvenkataswamy, L. Mickan, L. Unicomb, R. E. Rios, F. Huygens, and P. M. Giffard. 2006. Genotyping of Campylobacter jejuni using seven single-nucleotide polymorphisms in combination with flaA short variable region sequencing. J. Med. Microbiol. 55:1061-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robertson, G. A., V. Thiruvenkataswamy, H. Shilling, E. P. Price, F. Huygens, F. A. Henskens, and P. M. Giffard. 2004. Identification and interrogation of highly informative single nucleotide polymorphism sets defined by bacterial multilocus sequence typing databases. J. Med. Microbiol. 53:35-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sails, A. D., B. Swaminathan, and P. I. Fields. 2003. Utility of multilocus sequence typing as an epidemiological tool for investigation of outbreaks of gastroenteritis caused by Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4733-4739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shigemura, K., T. Shirakawa, H. Okada, K. Tanaka, S. Kamidono, S. Arakawa, and A. Gotoh. 2005. Rapid detection and differentiation of Gram-negative and Gram-positive pathogenic bacteria in urine using TaqMan probe. Clin. Exp. Med. 4:196-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stephens, A. J., F. Huygens, J. Inman-Bamber, E. P. Price, G. R. Nimmo, J. Schooneveldt, W. Munckhof, and P. M. Giffard. 2006. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus genotyping using a small set of polymorphisms. J. Med. Microbiol. 55:43-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stevenson, D. M., and P. J. Weimer. 2005. Expression of 17 genes in Clostridium thermocellum ATCC 27405 during fermentation of cellulose or cellobiose in continuous culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:4672-4678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stucki, U., J. Frey, J. Nicolet, and A. P. Burnens. 1995. Identification of Campylobacter jejuni on the basis of a species-specific gene that encodes a membrane protein. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:855-859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taboada, E. N., R. R. Acedillo, C. C. Luebbert, W. A. Findlay, and J. H. Nash. 2005. A new approach for the analysis of bacterial microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization: insights from an empirical study. BMC Genomics 6:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taboada, E. N., R. R. Acedillo, C. D. Carrillo, W. A. Findlay, D. T. Medeiros, O. L. Mykytczuk, M. J. Roberts, C. A. Valencia, J. M. Farber, and J. H. Nash. 2004. Large-scale comparative genomics meta-analysis of Campylobacter jejuni isolates reveals low level of genome plasticity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4566-4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wassenaar, T. M., and D. G. Newell. 2000. Genotyping of Campylobacter spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1816-1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]