Abstract

Changes in the diversity and structure of soil microbial communities may offer a key to understanding the impact of environmental factors on soil quality in agriculturally managed systems. Twenty-five years of biodynamic, bio-organic, or conventional management in the DOK long-term experiment in Switzerland significantly altered soil bacterial community structures, as assessed by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis. To evaluate these results, the relation between bacterial diversity and bacterial community structures and their discrimination potential were investigated by sequence and T-RFLP analyses of 1,904 bacterial 16S rRNA gene clones derived from the DOK soils. Standard anonymous diversity indices such as Shannon, Chao1, and ACE or rarefaction analysis did not allow detection of management-dependent influences on the soil bacterial community. Bacterial community structures determined by sequence and T-RFLP analyses of the three gene libraries substantiated changes previously observed by soil bacterial community level T-RFLP profiling. This supported the value of high-throughput monitoring tools such as T-RFLP analysis for assessment of differences in soil microbial communities. The gene library approach also allowed identification of potential management-specific indicator taxa, which were derived from nine different bacterial phyla. These results clearly demonstrate the advantages of community structure analyses over those based on anonymous diversity indices when analyzing complex soil microbial communities.

Soil microorganisms play an important role in maintaining soil quality in agriculturally managed systems and may be highly responsive to environmental influences (14, 33). Microbial soil characteristics may indicate changes in resource availability, soil structure, or pollution and represent one important key to understanding impacts of environmental and anthropogenic factors (11, 47, 65). Soil microbial diversity may represent the ability of a soil to cope with perturbations (1, 28, 32) and has been proposed as an indicator for soil quality (45). Therefore, analyses of soil microbial diversity and community structures appear to be essential when monitoring environmental influences on soil quality.

Arable soils have been reported to harbor a few hundred species per gram of soil, while pasture or forest soils may harbor more-complex communities consisting of several thousand species (66). Disturbances through agricultural treatments such as soil tillage, fertilization, and plant protection may favor certain species, resulting in reduced complexities of these communities (66). Agricultural treatments have been reported to influence soil microbial community structures (21, 40, 53, 63, 73) and to decrease soil bacterial diversity (37, 66). The DOK long-term field experiment in Switzerland was designed to investigate the effects of agricultural management factors on soil and plant parameters (38). In a previous study in the DOK experiment, soil bacterial community structures from three different agricultural management systems treated with farmyard manure (FYM), i.e., biodynamic (BIODYN), bio-organic (BIOORG), and conventional (CONFYM), along with an unfertilized (NOFERT) and a minerally fertilized (CONMIN) control were compared using terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis and ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis (RISA) (21). Increase of soil organic matter due to the application of FYM had a major influence on the bacterial community structures at the DOK site, as observed in previous studies of the same system (73) and other systems (4, 7, 48, 63). Crop effects were significant (73), whereas the effects of preceding crops were statistically not significant (21). This is consistent with reports on crop-dependent effects in other studies (19, 37, 40). Some differences among the FYM-treated systems, i.e., biodynamic, bio-organic, and conventional, were significant, but their magnitudes were lower than the effects caused by the actual crops (73). However, bacterial diversity and its comparison with the detected community structures remained unresolved. Because of consistent treatment effects on soil bacterial community structures (21, 73), the DOK field experiment offered a model system to compare bacterial diversity to the underlying community structures.

PCR-based genetic profiling techniques such as T-RFLP are promising techniques to assess differences in microbial communities. While they reveal analytic consistency, have high-throughput capability, and provide data compatible to standard statistical evaluation (22, 36, 41, 46), they appear limited for assessing microbial diversity. Recent technical developments for efficient screening of microbial communities by cloning and sequencing of ribosomal or functional genes (27, 69, 74) combined with suitable statistical analyses (3, 61) can provide more-detailed information on the composition and diversity of microbial communities. Comparison of community level genetic profiling data with results deduced from gene library analyses allows evaluation of the expressiveness of genetic-profiling approaches (18, 44). Even though community profiling and sequence analysis in agricultural soils have been reported (43, 57, 59, 63), their sensitivities in detecting environmental effects remained unassessed and there has been no direct comparison of these two approaches.

The five different DOK systems significantly influenced soil bacterial community structures as determined by T-RFLP analysis of soil nucleic acid extracts (21, 73). Analysis of terminal restriction fragments (T-RFs) among four independent replicates for each system revealed three major groups, represented by the conventional, biodynamic, and unfertilized systems. In the present study, bacterial diversity was determined for these three representative systems by sequence and T-RFLP analyses of 16S rRNA gene libraries. Results were compared to those previously obtained by soil community level T-RFLP profiling (21). The relationship between bacterial diversity and community structures in the gene libraries was assessed, with emphasis on the discriminatory potential of these parameters and the detection of potential system-specific indicator taxa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Agricultural management systems.

The DOK long-term experiment in Switzerland was established in 1978 and includes BIODYN, BIOORG, and CONFYM management, as well as CONMIN and NOFERT controls, which mainly differ in fertilizer application and plant protection strategies (21, 35, 38, 73). BIOORG and BIODYN are two organic farming systems receiving system-specific FYM and mechanical or alternative plant protection treatments. CONFYM received system-specific FYM and additional mineral fertilizer, as well as common chemical plant protection treatments. CONMIN received exclusively mineral fertilizer and the same plant protection applied in CONFYM, whereas NOFERT was not fertilized and plant protection was as in BIODYN. BIODYN, CONFYM, and NOFERT, which revealed representative differences in community level T-RFLP profiling (21), were selected for a detailed cloning and sequencing approach in the present study.

Amplification and cloning of bacterial 16S rRNA gene fragments.

Soil DNA extracts of four independent field replicates were prepared by a bead beating procedure (21), adjusted to a concentration of 10 ng DNA μl−1 in Tris-EDTA, and pooled. Four independent PCRs with primers 27F and 1378R (23) were performed with 20 ng template DNA for each pool in a total volume of 50 μl containing 1× PCR buffer (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 μM of each primer, 0.4 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.6 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin, and 2 U HotStar Taq polymerase (QIAGEN). PCR amplification was performed with initial hot-start denaturation for 15 min at 95°C followed by 30 cycles with denaturation for 45 s at 94°C, annealing for 45 s at 48°C, and extension for 2 min at 72°C, with final extension for 5 min at 72°C. Three microliters of each of the four replicate PCR products was cloned by using the pGEM-T Easy vector system cloning kit and Escherichia coli JM109 (Promega, Madison, WI).

Gene library screening.

Vector inserts were amplified by colony PCR with M13for (5′-TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGT-3′; Promega) and M13rev (5′-CAGGAAACAGC TATGACC-3′; Promega) vector primers in a total volume of 20 μl containing 1× PCR buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 μM of each primer, 0.4 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.6 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin, and 1 U HotStar Taq polymerase (QIAGEN). Initial hot-start denaturation for 15 min at 95°C was followed by 30 cycles with denaturation for 45 s at 94°C, annealing for 60 s at 60°C, and extension for 2 min at 72°C, with a final extension for 5 min at 72°C. PCR products were purified with Montage PCRμ96 plates (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and examined on agarose gels.

T-RFLP analysis.

Target genes were amplified from 1 μl M13 colony PCR product in 20-μl reaction volume with primers 27F (6-carboxyfluorescein labeled) and 1378R and the same conditions as described above, but with only 12 amplification cycles. Twenty microliters of PCR products was mixed with 40 μl concentration conversion buffer for MspI (CCBMspI; 4 mM Tris-HCl [pH 3], 50 mM NaCl, and 8 mM MgCl2) (22) and 5 μl restriction enzyme mixture containing 2 U restriction endonuclease MspI (Promega) in 1× supplied restriction enzyme buffer and incubated overnight at 37°C. Two microliters of digested PCR products was analyzed along with 0.2 μl MapMarker 1000 X-rhodamine (BioVentures, Murfreesboro, TN) and 12 μl HiDi formamide (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on an ABI Prism 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) with 36-cm capillaries filled with POP-4 polymer. T-RFLP profiles were analyzed using Genotyper v3.7 NT (Applied Biosystems) with a signal threshold of 50 relative fluorescence units.

Sequence analysis.

Partial sequences of cloned target genes were determined with primer UNI-516-rev (5′-TACCGCGGC[G/T]GCTGGCA-3′, position 532 to 516 on the E. coli sequence with GenBank accession number J01695; modified from the sequence described by Giovannoni et al. [17]) and corresponding vector primer T7 (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′; Promega) or SP6 (5′-ATTTAGGTGACACTATAG-3′; Promega) on M13 colony PCR products using the BigDye sequence terminator kit, v1.1 (Applied Biosystems). Sequences were analyzed on an ABI Prism 3100 genetic analyzer. Sequences were assembled using ContigExpress of the Vector NTI 9.0 software (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), trimmed at the 5′ and 3′ ends up to the primer sites, i.e., 27F and UNI-516-rev, and visually examined to detect base-calling errors. Sequence similarity searches for phylogenetic inference were performed with SEQUENCE_MATCH of the Ribosomal Database Project RDP-II v.9.26 (9) based on all entries with a size larger than 1,200 bp. Sequences with ambiguous affiliation were analyzed for chimeric nature with CHIMERA_CHECK 2.7 of RDP-II v.8.1. Sequences were defined as chimera only when consisting of fragments derived from different phyla.

Diversity analyses.

Sequences of all three gene libraries (BIODYN, CONFYM, and NOFERT) were pooled and aligned using the ClustalW routine in Vector NTI 9.0 (8). Constant grouping of sequences from the same phyla was tested by neighbor-joining cluster analysis based on Jukes and Cantor distance calculation using TreeCon 1.3 (67). Sequences were then split into phylum-specific groups, followed by refined alignment of these groups. Diversity analyses were performed using six different definitions of operational taxonomic units (OTUs). Three OTU definitions were based on different percent sequence identity levels (PSIL), i.e., 97% (PSIL97-OTU), 90% (PSIL90-OTU), and 80% (PSIL80-OTU), using FastGroup v1.2 (56). The other three OTU definitions were based on T-RFLP analysis, i.e., DNA sequence-defined in silico T-RF of each clone (T-RFseq-OTU), the experimentally determined T-RF of each clone (T-RFexp-OTU), and the T-RFs obtained from the soil bacterial community profiles (T-RFcom-OTU), which have been previously published (21). Gene library T-RFLP-based OTUs were restricted to T-RF sizes between 50 and 500 bp in order to allow for comparison to previously reported community level profiling data (21). In silico MspI T-RFLP analysis was performed using Expression 1.1 (Genamics, Hamilton, New Zealand). Community profiles of T-RFseq-OTU and T-RFexp-OTU abundances for comparison to the community level T-RFLP profile were plotted by using line plots with SigmaPlot 8.02 (SYSTAT Software, Chicago, IL). Observed OTU richness (Sobs), i.e., number of different OTUs per gene library or soil community profile, was determined for each of the six OTU definitions. Rarefaction analysis, displaying the number of OTUs detected versus the number of clones analyzed, was performed using the Analytic Rarefaction 1.3 calculator (24) and displayed using SigmaPlot 8.02 (SYSTAT Software). Maximal OTU richness was estimated using models of Michaelis-Menten (SMM), Chao1 (SChao1), and ACE (SACE) (26, 51). OTU diversity and distribution in the gene libraries were calculated using Shannon diversity (H) and evenness (E) indices (58). Calculations of Pearson product-moment correlations and Ward clustering of genetic profiles based on Euclidean distances were performed using Statistica version 6.1 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 1,904 partial 16S rRNA gene sequences reported here have been deposited in GenBank with accession numbers DQ827724 to DQ829627.

RESULTS

A total of 712 clones from BIODYN, 816 clones from CONFYM, and 720 clones from NOFERT were recovered. Only intact sequences revealing (i) both primer sites, i.e., 27F and UNI-516-rev, which defined the stretch for phylogenetic analyses, and (ii) unambiguously detectable T-RF peaks (T-RFexp) were included in the analysis, i.e., 600 BIODYN clones (84%), 691 CONFYM clones (85%), and 613 NOFERT clones (85%).

Phylogenetic affiliation.

Sequences were assigned to 11 different phyla, among which the phyla Actinobacteria (35 to 39%), Proteobacteria (26 to 33%), and Acidobacteria (11 to 13%) were most abundant (Table 1). Five to 6% of all sequences could not be unambiguously affiliated at the phylum level and were assigned as unclassified. For these sequences no indication for a chimeric nature at the phylum level was found (data not shown). Distributions of the phylogenetic groups were very similar among the three gene libraries (Table 1), revealing an overall correlation (r) of 0.99 (P < 0.001) for each of the three pairwise comparisons. Differences in abundance for each phylum among the gene libraries ranged from 1 to 4%, with an average difference of 1.2% ± 1.0%.

TABLE 1.

Phylogenetic categorization and relative abundance of soil bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences in the gene libraries of three farming systems in the DOK field experiment

| Phylogenetic group | No. of sequences (%) for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| BIODYN | CONFYM | NOFERT | |

| Gram positives | 254 (42)2 | 279 (40) | 245 (40) |

| Actinobacteria | 231 (39) | 240 (35) | 229 (37) |

| Firmicutes | 23 (4) | 39 (6) | 16 (3) |

| Proteobacteria | 154 (26) | 226 (33) | 193 (31) |

| Alphaproteobacteria | 96 (16) | 107 (15) | 92 (15) |

| Betaproteobacteria | 13 (2) | 33 (5) | 29 (5) |

| Gammaproteobacteria | 10 (2) | 26 (4) | 17 (3) |

| Delta/epsilonproteobacteria | 35 (6) | 60 (9) | 55 (9) |

| Acidobacteria | 76 (13) | 79 (11) | 69 (11) |

| Verrucomicrobia | 34 (6) | 18 (3) | 24 (4) |

| Bacteroidetes | 19 (3) | 18 (3) | 13 (2) |

| Gemmatimonadetes | 10 (2) | 9 (1) | 15 (2) |

| Chloroflexi | 9 (2) | 10 (1) | 10 (2) |

| Nitrospira | 3 (1) | 8 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Planctomycetes | 4 (1) | 2 (0) | 5 (1) |

| Cyanobacteria | 0 (0) | 2 (0) | 6 (1) |

| Unclassifieda | 37 (6) | 40 (6) | 30 (5) |

| Total | 600 (100) | 691 (100) | 613 (100) |

Sequence affiliations were not unambiguously determinable at the phylum level.

Richness and relative abundance of OTUs.

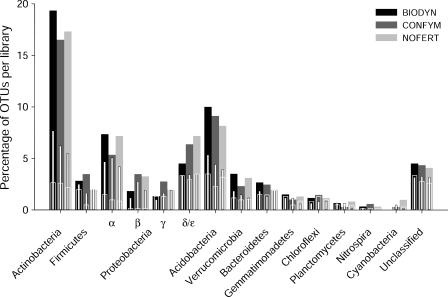

Classification of OTUs at a PSIL of 97 revealed an average Sobs of 385 ± 25 different OTUs in the three gene libraries, representing 61% ± 1% of the clones sampled (Table 2). The relative abundances of PSIL97-OTUs in each phylum were very similar for the farming systems (Fig. 1; filled bars), showing identical overall correlations (r = 0.98; P < 0.001) for each of the three pairwise comparisons. Maximal differences in relative abundance of PSIL97-OTUs among the three gene libraries were in the ranges of 3% (Actinobacteria), 2% (Alpha-, Gamma-, Delta/epsilonproteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Verrucomicrobia), and ≤1% (Bacteroidetes, Betaproteobacteria, Chloroflexi, Cyanobacteria, Firmicutes, Gemmatimonadetes, Nitrospira, and Planctomycetes). In silico T-RFLP analysis of cloned sequences revealed 93 to 94% of all T-RFs in the range between 50 and 500 bp (Table 2). An Sobs of 139 ± 4 different T-RF sizes (T-RFseq-OTUs) corresponding to 22% ± 2% of the clones analyzed was detected across the three agricultural treatment types (Table 2). The relative abundances of T-RFseq-OTUs in each phylum (Fig. 1; narrow white bars) were consistently lower, i.e., between 0 and 12% compared to PSIL97-OTU abundance, and were very similar among the three gene libraries, with pairwise overall correlations between 0.94 and 0.97 (P < 0.001). For comparison of data based on sequence identities and data based on T-RFLP analysis at similar resolutions, the PSIL yielding similar observed OTU richness as the T-RFseq-OTU was determined. Sobs at a PSIL of 90 revealed 137 ± 18 different OTUs representing 21% ± 2% of the clones analyzed (Table 2). Again, no pronounced differences were observed in the relative abundances of PSIL90-OTUs in each phylum (Fig. 1; small white framed bars), revealing pairwise overall correlations between 0.86 and 0.94 (P < 0.001). The richness of scorable T-RFs determined by soil community level T-RFLP analyses on four field replicates for each system revealed Sobs values of 76 ± 2 (BIODYN), 76 ± 1 (CONFYM), and 76 ± 1 (NOFERT) (21).

TABLE 2.

Richness and diversity estimations of OTUs of different definitions derived from soil bacterial 16S rRNA gene libraries from three farming systems in the DOK field experiment

| Farming system | No. (%) of clonesa | OTU definitionb | Sobs (%) | SMM | SChao1 | SACE | Coveragec ± SD | H | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence analysis | |||||||||

| BIODYN | 600 (100) | PSIL97 | 369 (62) | 1,068 | 971 | 1,031 | 36 ± 2 | 5.7 | 0.96 |

| CONFYM | 691 (100) | PSIL97 | 413 (60) | 1,259 | 1,153 | 1,332 | 33 ± 2 | 5.7 | 0.95 |

| NOFERT | 613 (100) | PSIL97 | 372 (61) | 1,080 | 953 | 1,093 | 36 ± 3 | 5.7 | 0.96 |

| BIODYN | 600 (100) | PSIL90 | 140 (23) | 256 | 348 | 320 | 46 ± 8 | 3.7 | 0.76 |

| CONFYM | 691 (100) | PSIL90 | 153 (22) | 288 | 496 | 367 | 42 ± 11 | 3.7 | 0.74 |

| NOFERT | 613 (100) | PSIL90 | 118 (19) | 184 | 204 | 199 | 60 ± 3 | 3.6 | 0.76 |

| T-RFLP analysis | |||||||||

| BIODYN | 560 (93) | T-RFseq | 142 (24) | 214 | 218 | 233 | 64 ± 3 | 4.3 | 0.87 |

| CONFYM | 652 (94) | T-RFseq | 141 (20) | 199 | 186 | 196 | 73 ± 3 | 4.3 | 0.87 |

| NOFERT | 574 (94) | T-RFseq | 135 (22) | 195 | 185 | 187 | 71 ± 2 | 4.3 | 0.87 |

| BIODYN | 560 (93) | T-RFexp | 172 (29) | 276 | 254 | 292 | 63 ± 4 | 4.6 | 0.90 |

| CONFYM | 649 (94) | T-RFexp | 169 (24) | 248 | 266 | 245 | 67 ± 3 | 4.6 | 0.89 |

| NOFERT | 570 (93) | T-RFexp | 153 (25) | 229 | 215 | 225 | 69 ± 2 | 4.5 | 0.89 |

Number of clones used for calculation. T-RFLP analysis revealed that 93 to 94% of the clone sequences produced T-RF sizes between 50 and 500 bp. Only these T-RFs were used in these calculations.

OTUs are based on PSIL (sequence analysis), i.e., 97 or 90%, or T-RF length (T-RFLP analysis), i.e., based on in silico restriction (T-RFseq) or experimentally retrieved (T-RFexp).

Percentage of coverage: Sobs/mean (SMM, SChao1, SACE) × 100.

FIG. 1.

Relative abundance of OTUs detected in the three soil bacterial 16S rRNA gene libraries obtained from three farming systems of the DOK field experiment. Numbers of OTUs for each bacterial phylum and gene library are displayed as percentages of the corresponding gene library size, i.e., BIODYN (100% = 600 sequences), CONFYM (100% = 691 sequences), and NOFERT (100% = 613 sequences). Three different OTU definitions, i.e., PSIL97-OTU (filled bars), PSIL90-OTU (small white framed bars), and T-RFseq-OTU (narrow white bars), were applied.

Estimated complexity of the gene libraries.

Determination of rarefaction curves, maximal-richness estimations, and diversity indices was performed with different OTU definitions, i.e., PSIL97-OTU, PSIL90-OTU, PSIL80-OTU, and T-RFseq-OTU (Fig. 2; Table 2). Differences among the rarefaction curves for the three gene libraries were small for all OTU definitions, showing a small deviation only for NOFERT at PSIL90. Rarefaction curves at PSIL90 and of in silico T-RFLP analysis (T-RFseq) were similar. Maximum PSIL97-OTU richness was estimated with three different models, i.e., SMM, SChao1, and SACE, and revealed 1,023 ± 49 for BIODYN, 1,181 ± 68 for CONFYM, and 1,042 ± 77 for NOFERT (Table 2). Based on these estimations, 33 to 36% of the diversities were covered by the applied sampling survey. H (Table 2) was 5.7 for all three gene libraries, whereas E varied between 0.95 and 0.96. High similarity among the gene libraries was also observed at the other OTU definitions (Fig. 2; Table 2).

FIG. 2.

Rarefaction analysis of soil bacterial 16S rRNA gene libraries from three agricultural farming systems of the DOK field experiment, displaying number of OTUs detected versus number of sequences analyzed. Aligned sequences were grouped using FastGroup v1.2 software at different OTU definitions, i.e., PSIL97-OTU, PSIL90-OTU, and PSIL80-OTU. In addition, an OTU definition based on unique in silico T-RFseq sizes is displayed. Rarefaction curves are displayed for each OTU definition.

Comparison of in silico and experimental T-RF sizes.

Community profiles compiled from experimental (T-RFexp; Fig. 3a) and in silico T-RFLP analysis (Fig. 3b) revealed similar patterns and distributions of predominant peaks. These T-RFLP profiles, derived from individual clones of the gene libraries, were similar to patterns obtained from soil bacterial community level T-RFLP profiling (Fig. 3c) (21). Averaged size shifting between T-RFseq size (bp) and T-RFexp size (relative migration unites [rmu]) was 1.6 ± 1.5 units. In total, 47% of all T-RFseqs revealed a size specific for one particular phylum, while the remaining T-RFseqs derived from two phyla (30%), three phyla (13%), four phyla (7%), five phyla (2%), or six phyla (1%).

FIG. 3.

T-RFLP profiles of bacterial 16S rRNA genes from DNA of CONFYM in the DOK field experiment. (a) Experimental T-RFLP profile compiled from T-RFexp of each clone in the corresponding gene library yielding T-RFexp between 50 and 500 rmu. (b) In silico T-RFLP profile compiled from sequence-predicted T-RFseq of each clone in the corresponding gene library yielding T-RFseq between 50 and 500 bp (c) Bacterial community level T-RFLP profile from soil DNA extracts in a range from 50 to 500 rmu as obtained in a previous study (21).

Community structures represented in the gene libraries.

For this analysis, sequences assigned to “unclassified” were integrated into the closest phylogenetic group as determined by cluster analysis (data not shown). A total of 899 different PSIL97-OTUs, i.e., 369 for BIODYN, 413 for CONFYM, and 372 for NOFERT, and a total of 272 different PSIL90-OTUs, i.e., 140 for BIODYN, 153 for CONFYM, and 118 for NOFERT, were found (Table 2). Differences in the relative OTU abundance in the profiles generated at PSIL of 97 and 90 were assessed by cluster analysis and revealed clear differentiation of NOFERT from BIODYN and CONFYM, while profiles from BIODYN and CONFYM were more similar (Fig. 4a and b). Identical dendrogram topologies were obtained when the “unclassified” sequences were omitted from the analysis, revealing 817 OTUs at PSIL97 and 223 OTUs at PSIL90 (data not shown). The topology was identical to the one obtained from soil bacterial community level T-RFLP profiling performed on pooled DNA extracts of four independent field replicates per farming system (Fig. 4c) (21).

FIG. 4.

Differences of bacterial 16S rRNA gene-based community structures between the three farming systems in the DOK experiment as determined by Ward clustering of Euclidean distances. Cluster dendrograms are based on OTUs derived from 16S rRNA gene libraries and from soil bacterial community level T-RFLP profiles. OTUs were defined at a PSIL of 97 with 899 OTUs (a) and at a PSIL of 90 with 272 OTUs (b). (c) Cluster analysis of soil bacterial community level T-RFLP profiles of pooled DNA extracts from four field replicates and based on intensities of 79 scorable T-RF sizes among four field replicates (community T-RFLP) (21).

Potential treatment-associated indicator taxa.

OTUs which revealed treatment specific differences and represent potential indicators (PI) were detected by applying the following definition. The potential indicator PSIL90-OTUs had to (i) include more than five sequences and (ii) reveal an increase or decrease in relative abundance of at least 50% for one particular farming system when compared to the other two. By applying this definition, 27 PSIL90-OTUs containing between 6 and 75 sequences per OTU were determined (Table 3). These 27 PI consisted of members from nine different phyla. No potential indicators were found in the groups Planctomycetes and Cyanobacteria. A decrease in NOFERT, i.e., PI24 to PI27, also indicated an increase in BIODYN and CONFYM, which were both treated with FYM and may therefore reflect indicator characteristics for FYM application. Analogously, a decrease in CONFYM, i.e., PI14 and PI15, also reflected an increase in BIODYN and NOFERT and therefore may have indicator characteristics for the biodynamic plant protection treatment. The least common levels of phylogenetic identity of these 27 potential indicator PSIL90-OTUs were very different, i.e., reaching from the domain level to the genus level (Table 3). Similarly, in silico MspI restriction of the sequences from each corresponding potential indicator PSIL90-OTU consisted of different numbers of T-RFseq sizes, i.e., between 1 and 25 different T-RFseq sizes between 50 and 500 bp for one particular OTU (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

OTUs revealing potential treatment-specific indicator characteristics

| PI OTU | No. of sequences | No. of T-RFsa | Taxonomic rank | LCLb | LCL identityc | Indicator systemd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI01 | 27 | 8 | Actinobacteria | Class | Actinobacteria | BIODYN ↑ |

| PI02 | 9 | 3 | Actinobacteria | Class | Actinobacteria | BIODYN ↑ |

| PI03 | 24 | 3 | Verrucomicrobia | Order | Verrucomicrobiales | BIODYN ↑ |

| PI04 | 6 | 2 | Verrucomicrobia | Order | Verrucomicrobiales | BIODYN ↑ |

| PI05 | 12 | 5 | Bacteroidetes | Genus | Chitinophaga | BIODYN ↑ |

| PI06 | 75 | 24 | Betaproteobacteria | Class | Betaproteobacteria | BIODYN ↓ |

| PI07 | 10 | 4 | Deltaproteobacteria | Order | Myxococcales | BIODYN ↓ |

| PI08 | 7 | 3 | Deltaproteobacteria | Genus | Geobacter | BIODYN ↓ |

| PI09 | 36 | 7 | Acidobacteria | Genus | Acidobacterium | BIODYN ↓ |

| PI10 | 6 | 1 | Chloroflexi | Domain | Uncultured bacterium | BIODYN ↓ |

| PI11 | 6 | 4 | Gammaproteobacteria | Genus | Pseudomonas | CONFYM ↑ |

| PI12 | 18 | 3 | Deltaproteobacteria | Order | Myxococcales | CONFYM ↑ |

| PI13 | 14 | 1 | Nitrospira | Genus | Nitrospira | CONFYM ↑ |

| PI14 | 7 | 3 | Actinobacteria | Family | Microbacteriaceae | CONFYM ↓ |

| PI15 | 8 | 0 | Alphaproteobacteria | Genus | Rhodoplanes | CONFYM ↓ |

| PI16 | 7 | 1 | Actinobacteria | Class | Actinobacteria | NOFERT ↑ |

| PI17 | 9 | 4 | Alphaproteobacteria | Family | Acetobacteraceae | NOFERT ↑ |

| PI18 | 6 | 6 | Gammaproteobacteria | Family | Xanthomonadaceae | NOFERT ↑ |

| PI19 | 8 | 5 | Deltaproteobacteria | Class | Deltaproteobacteria | NOFERT ↑ |

| PI20 | 9 | 5 | Deltaproteobacteria | Family | Cystobacteraceae | NOFERT ↑ |

| PI21 | 7 | 4 | Acidobacteria | Genus | Acidobacterium | NOFERT ↑ |

| PI22 | 21 | 4 | Acidobacteria | Genus | Acidobacterium | NOFERT ↑ |

| PI23 | 8 | 4 | Gemmatimonadetes | Genus | Gemmatimonas | NOFERT ↑ |

| PI24 | 7 | 5 | Firmicutes | Family | Clostridiaceae | NOFERT ↓ |

| PI25 | 7 | 3 | Deltaproteobacteria | Order | Myxococcales | NOFERT ↓ |

| PI26 | 7 | 2 | Acidobacteria | Domain | Uncultured Holophaga | NOFERT ↓ |

| PI27 | 6 | 1 | Chloroflexi | Domain | Uncultured Chloroflexi | NOFERT ↓ |

Number of different T-RF sizes between 50 and 500 bp determined by in silico analysis.

Least common level (LCL) on which phylogenetic affiliation was unambiguous.

Phylogenetic group of the corresponding OTU based on the least common level.

Farming systems revealing specifically increased (↑) or decreased (↓) abundance of the corresponding OTU.

DISCUSSION

DNA sequence and T-RFLP analyses of 1,904 16S rRNA gene amplicons cloned from three differently managed agricultural soils, i.e., BIODYN, CONFYM, and NOFERT, revealed highly similar diversities but strongly different compositions of the communities at defined phylogenetic levels. Although microbial diversity has been suggested as important indicator of soil quality and ecosystem stability (45, 62), the bacterial diversity based on common definitions was insensitive for detecting the agricultural influences in the present study. In contrast, differences in soil bacterial community structures detected by genetic profiling and sequence analysis were consistent and allowed identification of specific potential treatment-associated indicator taxa.

Most of the sequences obtained from the gene libraries could be assigned to known bacterial phyla (Table 1) which are commonly reported for arable soils (12, 25, 27) and originated to a major part (83% ± 1.0%) from Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia. These four phyla were reported to be predominant and ubiquitous in soils (25, 27), indicating that bacterial communities contained in the gene libraries were representative. Affiliation uncertainties at the phylum level for 5 to 6% of the sequences may be ascribed to several factors such as (i) insufficient coverage by databases (27) and novel candidate phyla (12, 25), (ii) short query sequences (71), and (iii) various PCR artifacts such as chimeras (50, 70). Constant grouping of sequences according to their phylogenetic inference at phylum level by cluster analysis (data not shown) and the assumption that PCR biases occur stochastically and at a constant extent (76) still legitimate comparative studies. Consistency in detecting differences in soil bacterial community structures among replicates by genetic profiling as previously shown in the same experimental system supports this assumption (21, 73). Similar distributions and abundances of the different phyla were found across all three agricultural treatments, i.e., BIODYN, CONFYM, and NOFERT (Fig. 1, Table 1). The large phenotypic diversity within and potentially high redundancy among some bacterial phyla may explain why certain environmental factors do not change total abundance at this phylogenetic level. It has recently been suggested (27) that environmental factors may influence the community at lower phylogenetic levels within major groups rather than changing the abundance at the phylum level.

Reports of the effects of fertilization, crop rotation, and pesticide application on soil microbial diversity as measured by parameters including richness, relative abundance, and distribution vary among different studies (6, 28, 34, 42, 63, 68), and the sensitivities of these parameters in responding to environmental influences are largely unknown. Diversity estimation by defining OTUs at different levels of sequence identities of cloned rRNA gene amplicons is one common approach in soil microbial ecology (16, 54, 60, 75). Observed richness, estimated maximum richness, Shannon diversity indices, and rarefaction analysis, representing richness and relative abundance of OTUs, at PSIL of 97, 90, and 80 and at the T-RF level indicated similar soil bacterial diversities among the farming systems (Fig. 2, Table 2), although differences could not be tested statistically since the gene libraries were not replicated. The marginally higher richness in CONFYM may be explained by the larger number of clones screened in this system (31), but estimates also depend on the mathematical model used (3). Furthermore, 600 to 700 sequences per library only partially covered soil bacterial species diversity (10), i.e., approximately one-third in the present study at PSIL97 (Table 2), and may represent mainly dominant genotypes, while less-abundant species remain insufficiently represented. Based on extrapolation of rarefaction curves, approximately 500,000 clones would have to be screened in order to completely cover the diversity in the analyzed libraries (data not shown). This large sampling effort demonstrates the need for fast and high-throughput monitoring tools such as T-RFLP analysis. It has been suggested that dominant species may contribute most to ecosystem processes (1, 12). Based on this assumption, a description of abundant species, as achieved by genetic profiling, would be suitable for environmental-effect studies, although whether dominant species truly reflect functional keystone species has been critically discussed (2).

Changes in microbial community structures may not necessarily lead to altered diversities, because changes of some taxonomic groups may be compensated by changes of others. It has been suggested that, for instance, species richness may exhibit less variability in response to environmental factors than species composition (15). Similar diversities, despite large changes in species composition, were observed in communities of mammals, birds, and plants (5), and here it was shown that this may also be the case for microbial communities in the DOK system. In addition, standard diversity parameters do not include taxonomic identity of the different groups but rather treat each OTU as an anonymous entity. For example, soils differing in management regimen and plant species composition showed no effect on bacterial diversity as determined by species richness and Shannon diversity of 16S rRNA gene libraries but tended to moderate changes in diversity of subgroups such as Alphaproteobacteria (42). This supports the suggestion that changes occur at lower phylogenetic levels rather than at major groups (27) and underscores the importance of assessing the underlying community compositions rather than just the anonymous diversity. In the present study, the applied agricultural factors altered the soil bacterial community structures but not soil bacterial diversity.

The FYM-treated systems BIODYN and CONFYM separated from the NOFERT system at PSIL97 and -90 (Fig. 4a and b). FYM-based agricultural management providing organic substrates and readily available nutrients may promote organisms with higher growth rates and faster adaptability (66) and may therefore lead to altered community composition when compared to unfertilized soils. In addition, organisms introduced by FYM application or secondary effects of the FYM application such as altered soil moisture, temperature, pH, and aggregate size or altered plant growth may also influence community composition (4, 38, 64). These differences were supported by reproducible differences in soil bacterial community structures in the DOK field by using community level T-RFLP, RISA, and substrate utilization profiling (Fig. 4c) (21, 73). Similarity of predominant taxonomic units among soil community level profiles and in silico and experimental gene library T-RFLP profiles was observed (Fig. 3). Resolution power of T-RFLP analysis was determined to be at a PSIL of 90 (Fig. 2, Table 2) and was therefore below the species level, which is commonly defined at a PSIL of 97 (16, 60). Cluster analysis at PSIL97, at PSIL90, and at community level T-RFLP yielded identical dendrogram topologies, supporting the suitability of the T-RFLP technique. Furthermore, community level genetic profiling by T-RFLP and RISA (21) as well as gene library analysis in the present study revealed very similar results, indicating validity of the data obtained. However, detection of differences in community composition seemed to depend on the applied phylogenetic level, revealing differences at lower levels such as PSIL97 and -90 (Fig. 4), but not at higher levels such as phyla (Fig. 1), which may be explained by the high phenotypic variation and therefore high redundancy within higher phylogenetic levels (27).

The T-RFLP approach was feasible to differentiate agricultural influences at certain phylogenetic levels but, in combination with previous reports, revealed also some limitations. (i) Discrepancies between in silico and experimental T-RF sizes, i.e., 1.6 ± 1.5 units in this study, may reduce specific inference of particular T-RFs in complex profiles (30, 52). Migration discrepancies for different T-RF sequences with the same length led to differences between in silico and experimental T-RFLP profiles (Fig. 3). (ii) Closely related sequences yielded very different T-RF sizes, and sequences from different phyla yielded similar T-RF sizes (18, 39, 55, 76). Fifty-three percent of all T-RF sizes occurred in more than one phylum and impeded phylogenetic inference based on T-RF sizes even at this high phylogenetic level. (iii) Formation of false T-RFs by formation of heteroduplexes and chimeric molecules, incomplete digestion, or nondigested single-stranded DNA has also been reported to bias the profiles (13, 18, 29, 50). The potential to affiliate phylogenetic information from gene libraries to complex community level T-RFLP profiles is therefore controversially discussed in the literature (18, 20, 44). The relatively large sampling survey in the present study indicated that phylogenetic inference based on soil community T-RFLP profiles with one restriction enzyme is strongly limited in complex communities.

Based on gene library data at PSIL90, 27 taxa from 9 different phyla could be defined, which revealed differences of at least 50% relative abundance between the gene libraries and may represent potential treatment-specific indicator taxa (Table 3). Genera such as Pseudomonas (PI11) and Chitinophaga (PI05), for example, have already been reported to be abundant in soils (27). Besides taxa that revealed increases in one particular system, i.e., NOFERT, BIODYN, or CONFYM, potential indicators were also found for FYM application (decrease in NOFERT) or for biodynamic management (decrease in CONFYM). The treatment specificity of these taxa has to be confirmed by specific primer design and quantitative PCR on soil DNA extracts (49, 72). Furthermore, these taxa have to be evaluated in other systems with different environmental factors such as soil type or climate conditions to substantiate their indicator function for the treatments considered here. This will represent a further step towards treatment-associated indicator diagnostics, which are prerequisites for environmental monitoring. Data presented here suggest that differences in agricultural management are reflected in soil bacterial community structures, but not in standard bacterial diversity estimations, and further demonstrated the applicability of the T-RFLP approach in environmental effect studies.

Acknowledgments

The DOK field experiment is a long-term project funded by the Swiss Federal Office for Agriculture (BLW). The project was supported by funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF).

The continuous high-quality management of the field experiment by the field teams of Agroscope Reckenholz-Tänikon and FiBL as well as support by farmers is greatly acknowledged. We thank Yvonne Haefele for technical assistance with cloning, sequencing, and community profiling. We are grateful to Jürg Enkerli, Roland Kölliker, and Manuel Pesaro for critical discussions and helpful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 October 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bardgett, R. D. 2002. Causes and consequences of biological diversity in soil. Zoology 105:367-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bengtsson, J. 1998. Which species? What kind of diversity? Which ecosystem function? Some problems in studies of relations between biodiversity and ecosystem function. Appl. Soil Ecol. 10:191-199. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohannan, B. J. M., and J. Hughes. 2003. New approaches to analyzing microbial biodiversity data. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:282-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bossio, D. A., K. M. Scow, N. Gunapala, and K. J. Graham. 1998. Determinants of soil microbial communities: effects of agricultural management, season, and soil type on phospholipid fatty acid profiles. Microb. Ecol. 36:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, J. H., S. K. M. Ernest, J. M. Parody, and J. P. Haskell. 2001. Regulation of diversity: maintenance of species richness in changing environments. Oecologia 126:321-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckley, D. H., and T. M. Schmidt. 2001. The structure of microbial communities in soil and the lasting impact of cultivation. Microb. Ecol. 42:11-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carpenter-Boggs, L., A. C. Kennedy, and J. P. Reganold. 2000. Organic and biodynamic management: effects on soil biology. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 64:1651-1659. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chenna, R., H. Sugawara, T. Koike, R. Lopez, T. J. Gibson, D. G. Higgins, and J. D. Thompson. 2003. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3497-3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cole, J. R., B. Chai, R. J. Farris, Q. Wang, S. A. Kulam, D. M. McGarrell, G. M. Garrity, and J. M. Tiedje. 2005. The Ribosomal Database Project (RDP-II): sequences and tools for high-throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:D294-D296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtis, T. P., and W. T. Sloan. 2004. Prokaryotic diversity and its limits: microbial community structure in nature and implications for microbial ecology. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7:221-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeLong, E. F., and N. R. Pace. 2001. Environmental diversity of bacteria and archaea. Syst. Biol. 50:470-478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunbar, J., S. M. Barns, L. O. Ticknor, and C. R. Kuske. 2002. Empirical and theoretical bacterial diversity in four Arizona soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3035-3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egert, M., and M. W. Friedrich. 2003. Formation of pseudo-terminal restriction fragments, a PCR-related bias affecting terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of microbial community structure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2555-2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elliott, L. F., and J. M. Lynch. 1994. Biodiversity and soil resilience, p. 353-364. In D. J. Greenland and I. Szabolcs (ed.), Soil resilience and sustainable land use. CAB International, Wallingford, United Kingdom.

- 15.Ernest, S. K. M., and J. H. Brown. 2001. Homeostasis and compensation: the role of species and resources in ecosystem stability. Ecology 82:2118-2132. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gevers, D., F. M. Cohan, J. G. Lawrence, B. G. Spratt, T. Coenye, E. J. Feil, E. Stackebrandt, Y. Van de Peer, P. Vandamme, F. L. Thompson, and J. Swings. 2005. Re-evaluating prokaryotic species. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:733-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giovannoni, S. J., E. F. Delong, G. J. Olsen, and N. R. Pace. 1988. Phylogenetic group-specific oligodeoxynucleotide probes for identification of single microbial cells. J. Bacteriol. 170:720-726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graff, A., and R. Conrad. 2005. Impact of flooding on soil bacterial communities associated with poplar (Populus sp.) trees. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 53:401-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grayston, S. J., S. Q. Wang, C. D. Campbell, and A. C. Edwards. 1998. Selective influence of plant species on microbial diversity in the rhizosphere. Soil Biol. Biochem. 30:369-378. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hackl, E., S. Zechmeister-Boltenstern, L. Bodrossy, and A. Sessitsch. 2004. Comparison of diversities and compositions of bacterial populations inhabiting natural forest soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5057-5065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartmann, M., A. Fliessbach, H.-R. Oberholzer, and F. Widmer. 2006. Ranking of crop and long-term farming system effects based on soil bacterial genetic profiles. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 57:378-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartmann, M., B. Frey, R. Kölliker, and F. Widmer. 2005. Semi-automated genetic analyses of soil microbial communities: comparison of T-RFLP and RISA based on descriptive and discriminative statistical approaches. J. Microbiol. Methods 63:349-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heuer, H., M. Krsek, P. Baker, K. Smalla, and E. M. H. Wellington. 1997. Analysis of actinomycete communities by specific amplification of genes encoding 16S rRNA and gel-electrophoretic separation in denaturing gradients. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3233-3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holland, S. M. 2001. Analytic rarefaction, version 1.3. University of Georgia, Athens.

- 25.Hugenholtz, P., B. M. Goebel, and N. R. Pace. 1998. Impact of culture-independent studies on the emerging phylogenetic view of bacterial diversity. J. Bacteriol. 180:4765-4774. (Erratum, 180:6793). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes, J. B., J. J. Hellmann, T. H. Ricketts, and J. M. Bohannan. 2001. Counting the uncountable: statistical approaches to estimating microbial diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4399-4406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janssen, P. H. 2006. Identifying the dominant soil bacterial taxa in libraries of 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1719-1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnsen, K., C. S. Jacobsen, V. Torsvik, and J. Sorensen. 2001. Pesticide effects on bacterial diversity in agricultural soils—a review. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 33:443-453. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanagawa, T. 2003. Bias and artifacts in multitemplate polymerase chain reactions (PCR). J. Biosci. Bioeng. 96:317-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaplan, C. W., and C. L. Kitts. 2003. Variation between observed and true terminal restriction fragment length is dependent on true TRF length and purine content. J. Microbiol. Methods 54:121-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kemp, P. F., and J. Y. Aller. 2004. Estimating prokaryotic diversity: when are 16S rDNA libraries large enough? Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2:114-125. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennedy, A. C. 1999. Bacterial diversity in agroecosystems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 74:65-76. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennedy, A. C., and K. L. Smith. 1995. Soil microbial diversity and the sustainability of agricultural soils. Plant Soil 170:75-86. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kent, A. D., and E. W. Triplett. 2002. Microbial communities and their interactions in soil and rhizosphere ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56:211-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirchmann, H. 1994. Biological dynamic farming—an occult form of alternative agriculture. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 7:173-187. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirk, J. L., L. A. Beaudette, M. Hart, P. Moutoglis, J. N. Khironomos, H. Lee, and J. T. Trevors. 2004. Methods of studying soil microbial diversity. J. Microbiol. Methods 58:169-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lupwayi, N. Z., W. A. Rice, and G. W. Clayton. 1998. Soil microbial diversity and community structure under wheat as influenced by tillage and crop rotation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 30:1733-1741. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mäder, P., A. Fliessbach, D. Dubois, L. Gunst, P. Fried, and U. Niggli. 2002. Soil fertility and biodiversity in organic farming. Science 296:1694-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manachini, P. L., D. Mora, G. Nicastro, C. Parini, E. Stackebrandt, R. Pukall, and M. G. Fortina. 2000. Bacillus thermodenitrificans sp. nov., nom. rev. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:1331-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marschner, P., D. Crowley, and C. H. Yang. 2004. Development of specific rhizosphere bacterial communities in relation to plant species, nutrition and soil type. Plant Soil 261:199-208. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marsh, T. L. 1999. Terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP): an emerging method for characterizing diversity among homologous populations of amplification products. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:323-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCaig, A. E., L. A. Glover, and J. I. Prosser. 1999. Molecular analysis of bacterial community structure and diversity in unimproved and improved upland grass pastures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1721-1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCaig, A. E., L. A. Glover, and J. I. Prosser. 2001. Numerical analysis of grassland bacterial community structure under different land management regimes by using 16S ribosomal DNA sequence data and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis banding patterns. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4554-4559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Noll, M., D. Matthies, P. Frenzel, M. Derakshani, and W. Liesack. 2005. Succession of bacterial community structure and diversity in a paddy soil oxygen gradient. Environ. Microbiol. 7:382-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2001. Environmental indicators for agriculture, vol. 3. OECD Publication Service, Paris, France.

- 46.Osborn, A. M., E. R. B. Moore, and K. N. Timmis. 2000. An evaluation of terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis for the study of microbial community structure and dynamics. Environ. Microbiol. 2:39-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pankhurst, C. E., K. Ophel-Keller, B. M. Doube, and V. Gupta. 1996. Biodiversity of soil microbial communities in agricultural systems. Biodivers. Conserv. 5:197-209. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peacock, A. D., M. D. Mullen, D. B. Ringelberg, D. D. Tyler, D. B. Hedrick, P. M. Gale, and D. C. White. 2001. Soil microbial community responses to dairy manure or ammonium nitrate applications. Soil Biol. Biochem. 33:1011-1019. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pesaro, M., and F. Widmer. 2006. Identification and specific detection of a novel Pseudomonadaceae cluster associated with soils from winter wheat plots of a long-term agricultural field experiment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:37-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qiu, X. Y., L. Y. Wu, H. S. Huang, P. E. McDonel, A. V. Palumbo, J. M. Tiedje, and J. Z. Zhou. 2001. Evaluation of PCR-generated chimeras: mutations, and heteroduplexes with 16S rRNA gene-based cloning. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:880-887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Raaijmakers, J. G. W. 1987. Statistical analysis of the Michaelis-Menten equation. Biometrics 43:793-803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenblum, B. B., F. Oaks, S. Menchen, and B. Johnson. 1997. Improved single-strand DNA sizing accuracy in capillary electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3925-3929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rousseaux, S., A. Hartmann, N. Rouard, and G. Soulas. 2003. A simplified procedure for terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the soil bacterial community to study the effects of pesticides on the soil microflora using 4,6-dinitroorthocresol as a test case. Biol. Fertil. Soils 37:250-254. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schloss, P. D., and J. Handelsman. 2005. Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1501-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schmitt-Wagner, D., M. W. Friedrich, B. Wagner, and A. Brune. 2003. Axial dynamics, stability, and interspecies similarity of bacterial community structure in the highly compartmentalized gut of soil-feeding termites (Cubitermes spp.). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6018-6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seguritan, V., and F. Rohwer. 2001. FastGroup: a program to dereplicate libraries of 16S rDNA sequences. BMC Bioinformatics 2:9. [Online.] http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2105/2/9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sessitsch, A., A. Weilharter, M. H. Gerzabek, H. Kirchmann, and E. Kandeler. 2001. Microbial population structures in soil particle size fractions of a long-term fertilizer field experiment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4215-4224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shannon, C. E., and W. Weaver. 1963. The mathematical theory of communication. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- 59.Smit, E., P. Leeflang, S. Gommans, J. van den Broek, S. van Mil, and K. Wernars. 2001. Diversity and seasonal fluctuations of the dominant members of the bacterial soil community in a wheat field as determined by cultivation and molecular methods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2284-2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stackebrandt, E., and B. M. Goebel. 1994. A place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S ribosomal-RNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44:846-849. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Staley, J. T. 1997. Biodiversity: are microbial species threatened? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 8:340-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stenberg, B. 1999. Monitoring soil quality of arable land: microbiological indicators. Acta Agric. Scand. 48:1-24. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sun, H. Y., S. P. Deng, and W. R. Raun. 2004. Bacterial community structure and diversity in a century-old manure-treated agroecosystem. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5868-5874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suzuki, C., T. Kunito, T. Aono, C.-T. Liu, and H. Oyaizu. 2005. Microbial indices of soil fertility. J. Appl. Microbiol. 98:1062-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tiedje, J. M., S. Asuming-Brempong, K. Nusslein, T. L. Marsh, and S. J. Flynn. 1999. Opening the black box of soil microbial diversity. Appl. Soil Ecol. 13:109-122. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Torsvik, V., L. Ovreas, and T. F. Thingstad. 2002. Prokaryotic diversity—magnitude, dynamics, and controlling factors. Science 296:1064-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Van de Peer, Y., and R. De Wachter. 1994. Treecon for windows—a software package for the construction and drawing of evolutionary trees for the Microsoft Windows environment. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 10:569-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van Elsas, J. D., P. Garbeva, and J. Salles. 2002. Effects of agronomical measures on the microbial diversity of soils as related to the suppression of soil-borne plant pathogens. Biodegradation 13:29-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Venter, J. C. 2004. Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the Sargasso Sea. Science 304:66-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.von Wintzingerode, F., U. B. Gobel, and E. Stackebrandt. 1997. Determination of microbial diversity in environmental samples: pitfalls of PCR-based rRNA analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 21:213-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang, Q., B. Chai, R. J. Farris, S. Kulam, D. M. McGarrell, G. M. Garrity, J. M. Tiedje, and J. R. Cole. 2004. The RDP-II (Ribosomal Database Project): the RDP sequence classifier, abstr. R-064, p. 607. Abstr. 104th Gen. Meet., New Orleans, La. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 72.Widmer, F., M. Hartmann, B. Frey, and R. Kölliker. 2006. A novel strategy to extract specific phylogenetic sequence information from community T-RFLP. J. Microbiol. Methods 66:512-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Widmer, F., F. Rasche, M. Hartmann, and A. Fliessbach. 2006. Community structures and substrate utilization of bacteria in soils from organic and conventional farming systems of the DOK long-term field experiment. Appl. Soil Ecol. 33:294-307. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Widmer, F., B. T. Shaffer, L. A. Porteous, and R. J. Seidler. 1999. Analysis of nifH gene pool complexity in soil and litter at a Douglas fir forest site in the Oregon Cascade Mountain Range. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:374-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Woese, C. R. 1987. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol. Rev. 51:221-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhou, J. Z., B. C. Xia, D. S. Treves, L. Y. Wu, T. L. Marsh, R. V. O'Neill, A. V. Palumbo, and J. M. Tiedje. 2002. Spatial and resource factors influencing high microbial diversity in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:326-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]