Abstract

The acyl coenzyme A (CoA) binding protein AcbA is cleaved to form a peptide (SDF-2) that coordinates spore encapsulation during the morphogenesis of Dictyostelium discoideum fruiting bodies. We present genetic evidence that the misspecification of cell types seen in mutants of the serine protease/ABC transporter TagA results from the loss of normal interactions with AcbA. Developmental phenotypes resulting from aberrant expression of the TagA protease domain, such as the formation of supernumerary tips on aggregates and the production of excess prestalk cells, are suppressed by null mutations in the acbA gene. Phenotypes resulting from the deletion of tagA, such as overexpression of the prestalk gene ecmB and the misexpression of the prespore gene cotB in stalk cells, are also observed in acbA mutants. Moreover, tagA− mutants fail to produce SDF-2 during fruiting body morphogenesis but are able to do so if they are stimulated with exogenous SDF-2. These results indicate that the developmental program depends on TagA and AcbA working in concert with each other during cell type differentiation and suggest that TagA is required for normal SDF-2 signaling during spore encapsulation.

We previously described TagA, a predicted serine protease/ABC transporter, and showed that it is required for proper cell differentiation during the development of Dictyostelium discoideum (7). Disruption of the ATPase domain of TagA by an insertion mutation in the tagA gene resulted in a mutant that produced an excess of prestalk cells and supernumerary prestalk tips on aggregates midway through development. Transcriptional profiling of development indicated that tagA insertion mutant (tagA1209; see Fig. 1A) cells have defects during early development, as well as a muted developmental program, compared to wild-type cells. Furthermore, cell type-specific genes failed to show cell type specificity in fruiting bodies of this tagA mutant. These data led to the conclusion that tagA is involved in specifying cell fate (7). Based on TagA's domain structure, an N-terminal protease attached to an ABC transporter, one attractive model is that TagA acts in a manner analogous to the processing and transport of peptide antigens into the endoplasmic reticulum of T cells through the combined action of the proteosome and the TAP1/TAP2 transporter (1). Support for this hypothesis should come from the identification of relevant TagA substrates, and that would provide a starting point for understanding the molecular mechanism of TagA function in cell type determination. TagA mRNA is enriched in prespore cells, so its potential substrates should also be found in prespore cells, but to date there are no obvious candidate proteins or peptides upon which TagA might act.

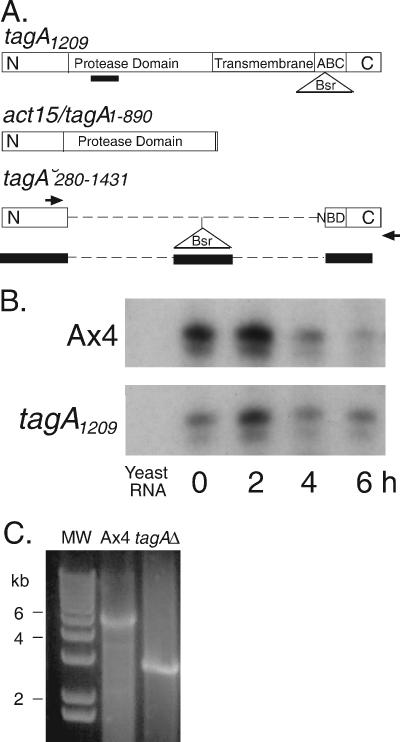

FIG. 1.

tagA structure, expression, and deletion. (A) The top diagram shows the structure of the tagA1209 insertion mutation shown within the tagA-coding region (open rectangles) (7). The parts of the gene that encode the protease, transmembrane, and ATP binding cassette (ABC) domains are indicated. The positions of the RNase protection probe (black bar) and the blasticidin resistance cassette (Bsr) are also shown. The middle diagram shows the portion of the tagA-coding region included in the TagA protease domain expression construct that is driven by an actin gene promoter. The bottom diagram shows the deduced structure of the partial deletion of the tagA gene. Dashed lines indicate the absence of the corresponding tagA-genic DNA. Black bars indicate the segments of DNA that are included in the knockout construct. The arrows indicate the position of the diagnostic PCR primers (not to scale). (B) RNase protection assays (RPA) of the wild type and tagA1209 using a probe located 5′ of the 1209 insertion site, indicated by a black bar in panel A. (C) PCR confirmation of the tagA partial deletion strain (tagAΔ), using genomic DNA of the mutant and wild type amplified with one oligonucleotide primer contained within the deletion construct described above for panel A and one primer corresponding to the genomic DNA on the 3′ side of the tagA-coding region. MW, molecular size marker.

Sporulation in Dictyostelium is a highly regulated process coordinated with the completion of fruiting body formation. At least two signaling peptides, known as spore differentiation factors 1 and 2 (SDF-1 and SDF-2), coordinate spore encapsulation with morphogenesis. SDF-1 is a cationic peptide released at the onset of culmination that induces encapsulation approximately 90 min later in a process that requires intervening protein synthesis (2). SDF-2 is an anionic peptide that induces rapid spore encapsulation by a process that does not depend upon subsequent protein synthesis (5). The protein precursor of SDF-2 was recently shown to be the acyl coenzyme A (CoA) binding protein AcbA (4). Interestingly, the human homolog of AcbA is the precursor of neuropeptides that modulate GABAA receptor function in central nervous system neurons (6). Although acbA is expressed in prespore cells during culmination, its product, AcbA, must be processed by the prestalk-specific serine protease/ABC transporter TagC (4, 5). We explored the possibility that TagA and AcbA might function together to specify cell fate, since TagA has a structure very similar to that of TagC and tagA is expressed in prespore cells, where acbA is also expressed.

We found that some of the previously described phenotypes resulting from disruption of tagA were the consequence of loss of the ABC transporter function while leaving the serine protease domain intact. These phenotypes, which appear to have been caused by unregulated protease activity, were suppressed by null mutations in acbA. On the other hand, misexpression of cell type-specific genes that result from the deletion of both the protease and ABC transporter domains of tagA were mimicked rather than suppressed by mutations in acbA. In addition, SDF-2 signaling is abrogated in tagA mutants. Together, these results support a direct interaction between TagA and AcbA that specifies cell fate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain construction, cell growth, and development.

The Dictyostelium discoideum strains used in this study are described in Table 1. Ax4 cells were grown in HL-5 liquid medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml streptomycin and 50 U/ml penicillin (16). Neomycin-resistant strains (Neor) and all of their derivatives were grown in HL-5 liquid medium supplemented with 20 μg/ml G418 (Geneticin). All strains were removed from drug-containing media 36 h prior to assay. Cells were plated for synchronous development on nitrocellulose filters as described previously (16). Transformation of Dictyostelium cells was performed according to previous guidelines (10) using a BTX 600 electroporation device (Genetronics, San Diego, CA). Inactivation of the tagA gene was achieved by homologous recombination at the genomic locus after electroporation of linearized DNA fragments. The tagA deletion construct was created such that the bulk of the tagA locus, including the ATP binding domain of the ABC transporter, the transmembrane helices, and the putative active residues of the serine protease domain, would be replaced by a 1.4-kb blasticidin S resistance cassette from pBsR503 (12). The DNA fragment containing the 5′ region of the tagA locus was synthesized by PCR and was placed into TA cloning vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen). This fragment consists of bases 2 to 888 of the tagA coding region with a base pair inserted between 882 and 883 to create a ClaI site. The 3′ region of the tagA locus was similarly synthesized by PCR, and the product consisted of bases 4207 to 5088 of the coding region. These 5′ and 3′ fragments were then cloned into XbaI/HindIII-digested pGEM3 plasmid (Promega) using an XbaI site added to the 5′ tagA fragment, a HindIII site added to the 3′ tagA fragment, and the ClaI sites that border the tagA deletion on both the 5′ and 3′ fragments. The blasticidin S resistance cassette was then placed into the ClaI site. This construct was linearized prior to transformation using HindIII and XbaI (Fig. 1). Integration at the native locus was determined by PCR analyses.

TABLE 1.

Dictyostelium strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Parental strain | Drug marker(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ax4 | Ax4a | Ax3 | 9 | |

| Ax4 [ecmA/GFP] | Ax4 | Neorb | 8 | |

| Ax4 [cotB/lacZ] | Ax4 | Neor | 7 | |

| Ax4 [act15/GFP] | Ax4 | Neor | 7 | |

| AK1142 | Ax4 [ecmB/lacZ] | Ax4 | Neor | 7 |

| AK1200 | tagA− | Ax4 | bsrb | This work |

| AK1201 | tagA− [ecmA/GFP] | Ax4 [ecmA/GFP] | Neor, bsr | This work |

| AK1202 | tagA− [ecmB/lacZ] | Ax4 [ecmB/lacZ] | Neor, bsr | This work |

| AK1203 | tagA− [act15/GFP] | Ax4 [act15/GFP] | Neor, bsr | This work |

| AK1204 | tagA− [cotB/lacZ] | Ax4 [cotB/lacZ] | Neor, bsr | This work |

| AK859 | tagA1209 | Ax4 | bsr | 7 |

| AK1215 | tagA1209 [cotB/lacZ] | Ax4 [cotB/lacZ] | Neor, bsr | 7 |

| AK1216 | tagA1209 [act15/GFP] | Ax4 [act15/GFP] | Neor, bsr | This work |

| acbA− | Ax4 | bsr | 4 | |

| AK1205 | acbA− [ecmA/GFP] | Ax4 [ecmA/GFP] | Neor, bsr | This work |

| AK1206 | acbA− [cotB/lacZ] | Ax4 [cotB/lacZ] | neor, bsr | This work |

| AK1207 | acbA− [ecmB/lacZ] | Ax4 [ecmB/lacZ] | Neor, bsr | This work |

| AK1208 | acbA− [act15/GFP] | Ax4 [act15/GFP] | Neor, bsr | This work |

| AK1209 | Ax4 [act15/tagA1-890] | Ax4 | Neor | This work |

| AK1210 | acbA− [act15/tagA1-890] | Ax4 [act15/tagA1-890] | Neor, bsr | This work |

| AK1211 | tagA−/acbA− | HL328 | bsr | This work |

| AK1212 | tagA−/acbA−[ecmA/GFP] | tagA−/acbA− | Neor, bsr | This work |

| AK1213 | tagA−/acbA− [ecmB/lacZ] | tagA−/acbA− | Neor, bsr | This work |

| AK1214 | tagA−/acbA− [cotB/lacZ] | tagA−/acbA− | Neor, bsr | This work |

Ax4 is used as the wild-type laboratory strain. Ax4 is an axenic derivative of NC4 derived from Ax3 (9).

Neor, neomycin resistance; bsr, blasticidin S resistance.

SDF-1 and SDF-2 activity assays.

SDF-1 and SDF-2 were separated on cation and anion exchange resins, respectively (2). Serial dilutions were added to KP cells that had been incubated at low cell density overnight, and spores were visually counted after 2 h (2). Units are given as the reciprocal of the highest dilution giving maximal activity. Cells dissociated from culminants were primed with 10 pM synthetic SDF-2. After 5 min of incubation, the cells were washed and 1 pmol recombinant AcbA added as indicated (3). SDF-2 in the supernatant was assayed after an additional 1-h incubation.

β-Galactosidase staining.

In all cases, images are of representative fingers or fruiting bodies. Experiments were performed multiple times on at least two independent strains. In the codevelopment experiments, the cotB/lacZ-marked strains were mixed with wild-type cells, marked with act15/GFP, at a ratio of 20:1 and allowed to form fruiting bodies. The pattern of green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression was used to assess admixture of the two strains and to ensure that mutant cells were present in the stalk before staining for β-galactosidase activity. Staining of developmental structures and spores for β-galactosidase was carried out as described previously (15). Cells were developed on white filters for the specified time, and the under-pad was removed. Cells were fixed for 10 min by gently dropping from a pipette onto the filter, 3.7% formaldehyde in Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, pH 7.0). The solution was wicked off from the edge of filter, and the filter was washed one time with Z buffer. Cells were permeablized for 20 min with 0.1% NP-40 in Z buffer, and the filter was washed with Z buffer. Staining was carried out with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-α-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) staining solution {0.5 ml 100 mM K3[Fe(CN)6], 0.5 ml 100 mM K4[Fe(CN)6], 0.5 ml 20 mM X-Gal, 1 ml 10 mM EGTA, 7.5 ml Z buffer} at 37°C for up to 24 h, and staining was stopped by rinsing with Z buffer. Structures were sometimes counterstained with 0.1% eosin Y in Z buffer for 1 min and rinsed with Z buffer.

RESULTS

Creation of a tagA deletion mutant.

The previously characterized tagA1209 mutation was generated by an insertion that interrupted the nucleotide binding domain of the ABC transporter (7). We previously showed that tagA1209 failed to accumulate detectable mRNA throughout development using an RNase protection assay that detected coding sequences downstream of the insertion site. We suspected that the tagA1209 mutant might still be able to express the protease domain encoded in the 5′ half of the tagA gene. Probing for mRNA upstream of the 1209 insertion showed that, indeed, this portion of the tagA mRNA was present during early development, although at somewhat lower levels than in wild-type cells (Fig. 1A and B). Thus, it is possible that the protease domain of TagA is expressed in the tagA1209 mutant. Therefore, we generated a tagA deletion mutant that replaced the serine protease domain and most of the ABC transporter domain with a blasticidin resistance cassette (tagAΔ; see Fig. 1A). A new deletion strain was isolated by PCR-based identification of the appropriate homologous recombinant among a population of Dictyostelium transformants (Fig. 1C).

The insertion mutant tagA1209 forms characteristic multitipped fingers following aggregation that are not seen in wild-type strains (7). Aggregation of the tagA deletion mutant produced a single gnarled finger, suggesting the multitipped phenotype of the insertion mutant results from alterations in the activity of the serine protease when it is not associated with the ABC transporter (Fig. 2A). To directly test this possibility, we placed the protease-coding sequence from tagA in an expression cassette under control of the constitutive actin 15 promoter (act15/tagA1-890; see Fig. 1A). When this construct was expressed in the wild-type strain Ax4, the cells formed multitipped fingers following aggregation that were similar to those seen in the tagA1209 insertion mutant (Fig. 2A).

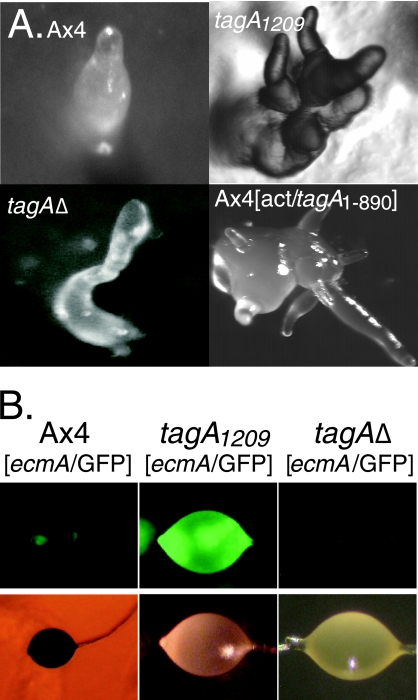

FIG. 2.

Multitipped phenotype and the overproduction of ecmA-positive cells. (A) The developmental morphology of mutants after 16 h of development. In the wild-type strain (Ax4), a single finger emanates from an aggregate that had formed a single tip earlier. Both the tagA insertion mutant (tagA1209) and the Ax4 strain expressing the protease domain of TagA (Ax4[act/tagA1-890]) form multiple fingers from a single aggregate. (B) Localization of cells expressing ecmA/GFP in the upper and lower cups of sori after 24 h of development.

The tagA1209 insertion mutant also produces about twice the normal number of ecmA-expressing cells, some of which localize to the upper and lower cups of the sorus during culmination (7). When we introduced an ecmA/GFP construct into the tagA deletion strain, there was no obvious overproduction of ecmA-positive cells (Fig. 2B). This suggests that the overexpression of ecmA-positive cells also results from alterations in the regulation of the serine protease rather than loss of the ABC transporter activity of TagA.

Evidence for the interaction of TagA and AcbA.

The substrate for the protease activity of TagA is not known, but that of a related serine protease/ABC transporter, TagC, is likely to be the acyl-CoA binding protein AcbA, which is the precursor of the culmination signaling peptide SDF-2 (4). Therefore, we explored the possibility that the TagA protease acts on AcbA, perhaps during early development, before TagC is expressed. If this is the case, then multitipped aggregates should not be observed in acbA mutants. In fact, the multitipped phenotype was not observed in the acbA mutant or the acbA−/tagA1209 double mutant (Fig. 3A). Moreover, expression of the TagA protease in an acbA-null strain did not lead to multitipped aggregates as it does in wild-type cells (Fig. 3B). Likewise, a null mutation in acbA suppresses the overproduction of ecmA-positive cells in the tagA1209 insertion mutant (compare Fig. 2B with 3C). These genetic interactions suggest that the TagA protease functions with AcbA to control the number of tips on aggregates and the number of ecmA-positive cells in fruiting bodies.

FIG. 3.

Phenotypic suppression by acbA-null mutations. (A) Morphology of acbA− strains after 16 h of development. The multiple fingers that emanate from multitipped aggregates of the tagA1209 insertion mutant (left panel; this is the same image as that in Fig. 2A) are not observed in the acbA mutant or the acbA tagA1209 double mutant. (B) Expression of the TagA protease domain (act15/tagA1-890) does not result in the multitipped phenotype in the acbA− genetic background (the left panel is the same image as that in Fig. 2A). (C) Localization of cells expressing ecmA/GFP in the upper and lower cups of sori after 24 h of development. In comparison to the TagA insertion mutant shown in Fig. 2B, the excess ecmA-positive cells were not observed in the sori of the tagA1209 acbA double mutant.

tagA mutants do not produce SDF-2.

AcbA is found only in prespore cells before it is released during culmination and processed by TagC into the 34-amino-acid peptide SDF-2 that triggers spore encapsulation (4, 5). TagA protein is present in all cells in the early stages of development, and the expression of its mRNA becomes restricted to prespore cells and spores, thus, it may be acting on AcbA within cells during earlier stages of development. To test whether there might be further connections between TagA and AcbA, we determined whether tagA1209 and tagAΔ strains could generate SDF-2 activity. Using a bioassay in which less than 1 pM SDF-2 can be detected by its ability to induce rapid spore encapsulation in a strain overexpressing the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase PkaC, we found that neither of the tagA mutant strains produced any measurable SDF-2 activity (Table 2). Extracellular SDF-2 signaling displays a form of positive feedback that probably serves to propagate the signal for spore encapsulation during culmination (3). Thus, it is possible to “prime” signaling-competent cells with exogenous SDF-2 and monitor the production of endogenous SDF-2. To further test for the production of SDF-2 in the mutants, we primed cells with 10 pM SDF-2 peptide for 5 min, washed out the peptide, and then measured the amount of SDF-2 released after a further 60 min of incubation. Again, the tagA deletion mutant failed to produce detectable SDF-2 (Table 2). The failure to make SDF-2 is unlikely to be the result of a defect of a much earlier development event, since these strains did produce the other spore differentiation factor, SDF-1 (Table 2), and strains lacking either TagA or AcbA are still able to sporulate, although they do so asynchronously and at reduced levels (3, 7). The apparent overproduction of SDF-1 activity in the tagA deletion mutant and the acbA mutant is suggestive of a negative feedback loop between TagA (or SDF-2) signaling and SDF-1 production.

TABLE 2.

SDF-1 and SDF-2 productiona

| Strain | Amt of SDF-1 in sori (U/103 cells) | Amt of SDF-2 in sori (U/103 cells) | Amt of primed SDF-2 (U/103 cells) | Amt of primed plus AcbA SDF-2 (U/103 cells) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ax4 | 2 × 103 | 104 | 1.5 × 104 | >104 |

| acbA− | 104 | <0.02 | <2 | >104 |

| tagA1209 | 2 × 103 | <0.01 | ND | ND |

| tagAΔ | 104 | <0.01 | <2 | >2 × 104 |

For priming, cells dissociated from 22-h developing cells (culminants) were exposed to 10 pM SDF-2 with or without the SDF-2 precursor protein AcbA (1 pmol) added (see the text for details). ND, not done.

The prestalk-specific serine protease/ABC transporter TagC is known to be required for the generation of SDF-2 peptides from AcbA protein (4, 5). Thus, the failure of tagAΔ mutants to secrete SDF-2 might be caused by compromised TagC function in these cells. The fact that cells can process exogenously provided AcbA provided a means to assess TagC activity in the prestalk cells of the tagA mutant (3, 4). We tested whether tagAΔ cells are able to process recombinant AcbA into SDF-2, as described previously, by dissociating tagAΔ cells from the mid-culminant stage of development (22 h), “priming” them with 10 pM SDF-2 peptide for 5 min, washing out the peptide, and finally adding 1 pmol of recombinant AcbA protein (3). After a 60-min incubation, the supernatant was found to contain over 104 U of SDF-2 activity, which represents much more SDF-2 peptide than was added for priming (Table 2). Thus, the deletion of tagA does not appear to interfere in an obvious way with the expression of TagC or the ability of prestalk cells to process AcbA or respond to low levels of SDF-2.

Phenotypes found in both tagA− and acbA− mutants.

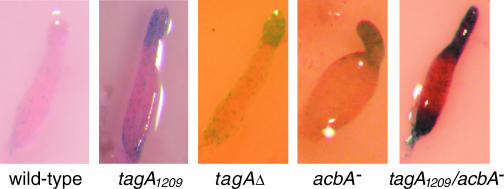

We previously showed that the tagA1209 insertion mutant formed slugs with an overabundance of cells expressing the PstB marker, ecmB. These cells ultimately accumulate in the lower cup and outer basal disk of fruiting bodies (18). The newly made tagA deletion mutant also produced an excess number of ecmB-positive cells, suggesting that this phenotype does not result from unregulated protease activity but rather from a complete lack of TagA function (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the acbA-null strain and the tagA1209 acbA double mutant also formed slugs with excess ecmB-positive cells (Fig. 4). That the tagA and acbA mutants share this unusual phenotype further suggests that TagA and AcbA function together in a process of cell specification.

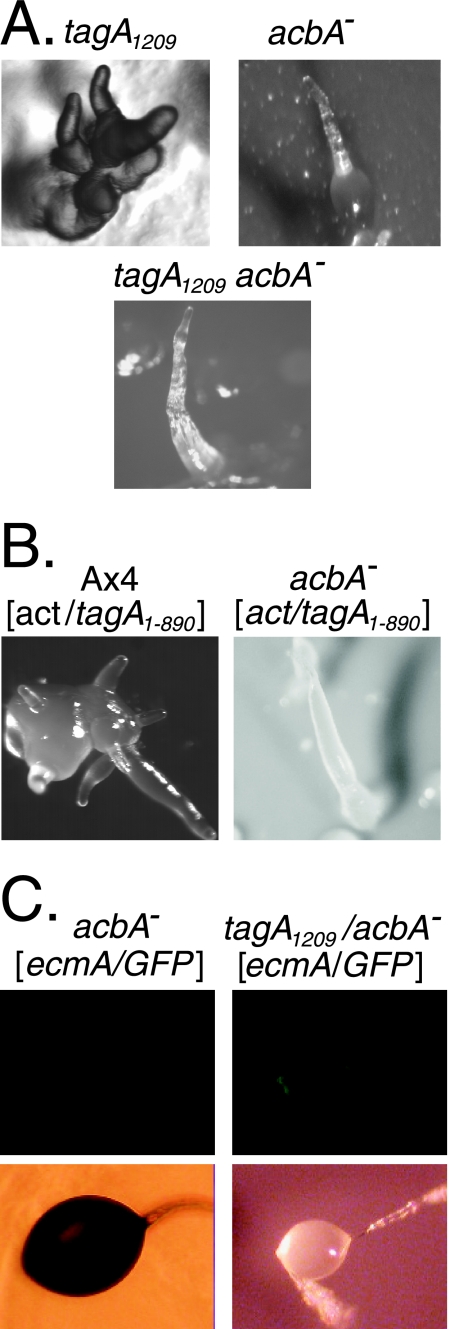

FIG. 4.

ecmB expression in migrating slugs. EcmB-positive cells were visualized in migrating slugs using the ecmB/lacZ reporter construct. Slugs were fixed after 18 h of development, permeablized, and stained for β-galactosidase activity. An overabundance of ecmB-expressing cells are observed in the anterior of each mutant slug.

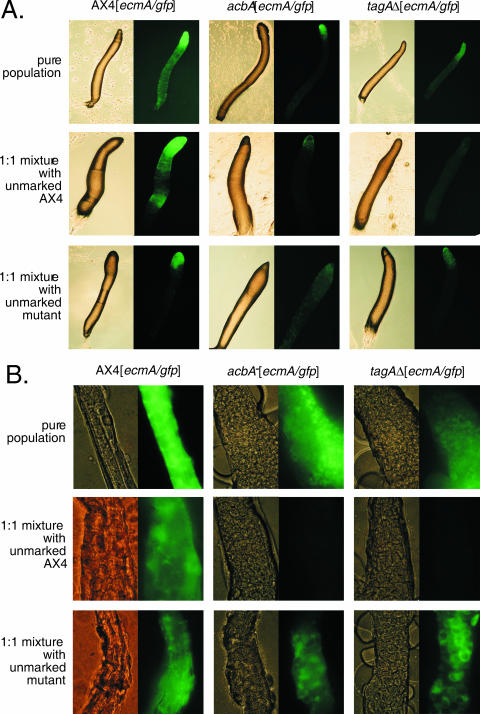

Defects of the tagAΔ and acbA mutants in specifying the prestalk cells are also apparent in the PstA and PstO cell populations. We followed PstA and PstO cell development in these mutants with a GFP reporter construct driven by the ecmA promoter (18). In pure populations of migrating slugs, the level of expression of this reporter gene appears to be reduced in both the tagAΔ and acbA mutant relative to the wild type (Fig. 5A, upper panels). This is a consistent result that was observed in every slug examined and in multiple transformants of the reporter construct into the mutant parental strains. When these mutants were mixed 1:1 with unmarked wild-type cells, the mutants appear to be compromised in their ability to form ecmA-expressing cells (Fig. 5A, middle panels). With both mutants a range of chimeric slugs was observed, from those with fairly normal mutant contribution to the PstA and PstO cell populations (Fig. 5A, center panels) to those where only a few PstA cells appear to be produced by the mutant cell population (Fig. 5A, middle-right panels). This defect in the production of ecmA-expressing cells was not detected when the mutants were mixed with unmarked mutant cells (Fig. 5A, lower panels).

FIG. 5.

Defective tagA and acbA mutant prestalk cells in chimeras. (A) Ax4 (wild type), acbA mutant cells, and tagA deletion (tagAΔ) cells expressing GFP under the control of the prestalk promoter ecmA were allowed to develop to the slug stage as pure populations (top panels), as 1:1 mixtures with unmarked wild-type AX4 cells (middle panels), or with unmarked mutant cells (bottom panels). Only the AX4 mixture with unmarked acbA mutant cells is shown, and the mixture with unmarked tagA mutant cells gave similar results (data not shown). Only the marked mutants mixed with unmarked mutants of the other genotype are shown. Mixtures of marked mutants with unmarked mutants of the same genotype gave similar results (data not shown). The fluorescence panels were all imaged with the same exposure times, and representative slugs are shown. (B) The mixtures described in panel A were allowed to develop into fruiting bodies, and segments of the resulting stalks were imaged with the same exposure times. The GFP appears to be excluded from the stalk cell vacuoles, giving a reticulated pattern. The level of fluorescence observed in the middle panels is similar to that of GFP-negative slugs (data not shown). In the bottom-left panels, only the control mixture with tagAΔ mutant cells is shown, but the mixtures with acbA mutant cells were similar.

While the tagAΔ and acbA mutants are capable of making grossly normal stalks when developed as pure populations, they appear to be unable to contribute to the stalk cell population in the presence of wild-type cells. When mutant cells were mixed at a 1:1 ratio with wild-type cells and allowed to form fruiting bodies, no mutant stalk cells were observed within the entire length of the stalks. This is illustrated with high-power images of stalk sections that are shown in Fig. 5B (middle panels). This experiment was also carried out with mutant cells marked with a general cell marker, actin/GFP, and the same results were obtained (data not shown).

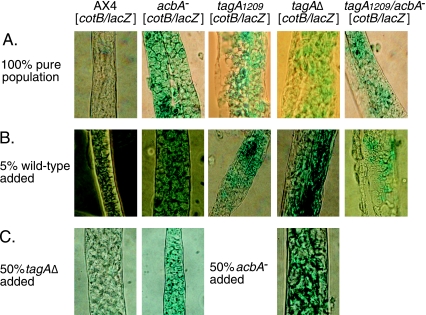

The tagA insertion mutant expresses the prespore cell marker cotB/lacZ in vacuolated stalk cells within the stalk tube, again suggesting imperfections in prestalk or stalk cell specification (7). At the time we reported this finding, such a phenotype had not been previously described. Surprisingly, we observed this phenotype in the tagA deletion mutant as well as in strains lacking AcbA (Fig. 6A). To test whether errors in cell fate specification in these mutants resulted from a lack of intercellular signaling at any time during development, we developed them together with wild-type cells and looked for the presence or absence of lacZ-positive stalk cells. Since tagA and acbA mutant cells do not form stalk cells when mixed 1:1 with wild-type cells (see above), we had to reduce the proportion of wild-type cells in the mixtures to ensure that some of the mutant cells contributed to the stalk of the chimera. We found that by adding 5% wild-type cells to the mixtures, some of the mutant cells differentiated as stalk cells. The wild-type partner in these experiments was tagged with the actin/GFP marker to assess their contribution to the stalk. Visual inspection by fluorescence microscopy confirmed that both wild-type and mutant cells entered the stalk tubes of chimeric fruiting bodies (data not shown). Mutant cells in the mixed stalk were seen to have expressed the cotB/lacZ reporter (Fig. 6B). Within the limits of the use of only a small proportion of wild-type cells in the mixtures, these results suggest that mutations in either tagA or acbA result in a cell-autonomous defect in stalk cell differentiation.

FIG. 6.

cotB gene expression in tagA and acbA mutants. (A) A cotB/lacZ reporter construct was used to assess the aberrant expression of the prespore-specific cotB gene in stalk cells. Fruiting bodies were fixed and stained for β-galactosidase activity after 24 h of development. A single representative section of the stalk produced by each strain is shown. (B) The cotB/lacZ-marked strains shown in panel A were mixed with 5% wild-type cells, marked with act15/GFP, and allowed to form fruiting bodies. GFP expression was used to ensure that mutant cells were present in the stalk before staining for β-galactosidase activity. (C) The cotB/lacZ-marked strains shown in panel A were mixed 1:1 with indicated mutant cells, marked with act15/GFP, and allowed to form fruiting bodies. GFP expression was used to determine if the stalk contained a roughly equal proportion of the two cell types before staining for β-galactosidase activity. Images are of representative fruiting bodies. Experiments were performed multiple times on at least two independently obtained strains.

The inability to form stalk cells in admixtures with wild-type cells is a defining phenotype of the tagB and tagC mutants (14). It is also well documented that TagC and AcbA are part of the spore encapsulation pathway (4, 5, 17), and the shared stalk cell production defect of tagA, tagB, tagC, and acbA mutants suggests some commonality of function in prestalk/stalk cell differentiation. To further explore the relationship between TagA and AcbA, we examined mixtures of the tagA and acbA mutants to test whether (i) either mutant could exclude the other from the stalk cell population and (ii) either mutant could rescue the other's defect in cell fate as revealed by misexpression of the cotB promoter. For each of these experiments, we carried out two control experiments where one or the other of the strains in each mixture was marked with an actin/GFP marker to ensure admixture. Except for the case of the exclusion of mutant cells from the stalk when mixed with wild type, all mutant/mutant mixtures produced evenly mixed cells within slugs and fruiting bodies, including the stalks (data not shown). The acbA and tagA mutant mixtures (1:1 ratio) in which one of the strains was labeled with ecmA/GFP produced stalks in which about half of the cells were GFP positive (Fig. 5B, lower panels). This indicates that neither mutant influences the other's terminal differentiation into stalk cells. In the mixtures (1:1) where one of the mutants was labeled with cotB/lacZ and the other with act15/GFP, inspection by fluorescence microscopy of the resulting stalks revealed that they were roughly even mixtures of the two mutants (data not shown). Stalks from the same mixtures were also stained with X-Gal for β-galactosidase activity and revealed roughly equal numbers of lacZ-positive and lacZ-negative cells (Fig. 6C). In addition, neither of the mutant/wild-type mixtures resulted in misexpression of cotB in the wild-type cells (one mixture is shown in Fig. 6C). This indicates that the misexpression of cotB could not be induced in wild-type cells by either mutant or rescued in either mutant by the presence of the other mutant.

DISCUSSION

Our previous report of the consequences of disrupting the tagA gene described a complex set of phenotypes involving the overexpression and misexpression of cell type specific genes, cell type proportioning and morphogenesis (7). Here we have shown that mutations in the acyl-CoA binding protein gene, acbA, suppress some of the phenotypes caused by tagA mutations and mimic others. These genetic interactions and phenotypic similarities suggest that TagA and AcbA function together, either directly or indirectly, to control cell differentiation.

The multitipped phenotype previously described for the tagA insertion mutant is likely the consequence of the expression of a truncated version of TagA. TagA mRNA encoding the serine protease domain but lacking the ABC transporter domain was observed to accumulate during early development of the insertion mutant tagA1209. The multitipped phenotype was also observed when the TagA serine protease domain was expressed in wild-type cells. These results, combined with the observation that the tagA deletion mutant does not have a multitipped aggregate phenotype, indicates that the tagA1209 allele is allomorphic, rather than null, for TagA function as we had previously supposed (7). The suppression of this multitipped phenotype in these strains by null mutations in acbA can be interpreted in several ways. The protease activity in tagA1209 cells is likely to be unregulated or misregulated as the result of its separation from the ABC transporter domain of TagA, so it may hydrolyze its natural substrate constitutively or ectopically or may hydrolyze an entirely new substrate. AcbA may regulate TagA's access to its natural substrate or prevent access to abnormal substrates while carrying out its normal function as an acyl-CoA binding protein. The AcbA homolog in yeast is known to be involved in membrane trafficking, so the loss of AcbA in Dictyostelium might alter the cellular localization or disposition of many proteins (13). Alternatively, the multitipped phenotype could result from aberrant proteolysis of AcbA itself. This is plausible, since TagA and AcbA are both predicted to be associated with membranes and since the TagA homolog TagC is required to process AcbA into the SDF-2 peptide (4, 5). The lack of SDF-2 biogenesis from either the tagA insertion strain or the tagA deletion strain supports the hypothesis that AcbA is a substrate of TagA, at least during culmination. By the same argument, the excess of ecmA-positive cells in the upper and lower cups of tagA1209 mutant sori that is suppressed by a null mutation in acbA also appears to be due to abnormal proteolysis, perhaps of AcbA itself.

On the other hand, the excess ecmB-positive cells at the slug stage, the inability to contribute to the PstA lineage (stalk) in chimera with wild-type cells, and the misexpression of cotB in the stalk cells of fruiting bodies was observed in both the tagA insertion and deletion mutants. These phenotypes appear to be due to the lack of TagA function. Consistent with this idea, these phenotypes were not suppressed by acbA mutations and so do not appear to result from the abnormal hydrolysis of proteins or abnormal processing of AcbA. However, the surprising finding that acbA mutants produce all these same phenotypes suggests that both AcbA and TagA are required for the same aspect of cell fate specification.

While the fruiting bodies of tagA and acbA mutants are not grossly abnormal morphologically, the presence of cotB-positive stalk cells within their stalks indicates that the transcriptional regulation within the cells is altered. There are two equally plausible explanations for this unprecedented phenotype. Given the several-hour half-life of the β-galactosidase expressed from the reporter that we used, it may be that the stalk cells of tagA and acbA mutants differentiate as prespore cells for some period of their developmental history. Alternatively, it could be that the suppression of cotB expression in PstA cells and/or stalk cells requires both TagA and AcbA. The fact that the tagA and acbA mutants are also excluded from the PstA cell lineage when they are mixed with wild-type cells argues they are defective in specifying this prestalk cell type. Indeed, the gnarled-finger morphology seen in the acbA and tagA null mutants is strikingly similar to that of the ecmA knockout (11). This further supports the evidence of lower ecmA expression in all the mutants (but not in the tagA1209 mutant), as determined by ecmA/GFP expression (see Fig. 2B, 3C, and 5A). The inability of wild-type cells to correct the cell specification defects in the tagA and acbA mutants as measured by the presence of cotB-positive cells within stalk tubes suggests that the phenotype is cell autonomous. One caveat to this interpretation is that we could only examine the differentiation of the mutants' stalk cells when mixed with 5% wild-type cells, because the wild-type cells are better able to form stalk cells than either mutant and appear to “out-compete” them for stalk cell differentiation. However, 1:1 mixtures of acbA and tagAΔ mutants produced stalks that had equal representation of both mutants and where both mutants displayed cotB misexpression. The fact that neither mutant prevents the other mutant from forming stalk cells suggests that either the two mutants produce equally defective prestalk cells and so do not “compete” with each other or that the two mutants are defective in the same cell specification pathway, so that the mixed mutants make stalks as if they were a pure population of either mutant. The most favorable interpretation of the latter possibility is that TagA and AcbA function in the same intracellular signaling pathway, but other possibilities are not excluded by these experiments. However, these experiments do appear to formally rule out the possibility that TagA and AcbA are required for distinct extracellular signaling events required for proper cell fate specification and are consistent with a cell-autonomous cell fate defect in both mutants.

AcbA is found only in prespore cells during late development, and it must be secreted in order for it to be processed by the serine protease activity of TagC that is found on prestalk cells (4, 14). The proteolytic product, SDF-2, is the ligand of the receptor histidine kinase DhkA found on the surface of both prespore and prestalk cells (17). Binding of SDF-2 to DhkA inhibits phosphorelay, resulting in an increase in PKaC activity and rapid encapsulation of prespore cells (4). While the lack of release of SDF-2 in both the tagAΔ and acbA− strains may account for some of their developmental abnormalities, it cannot account for all the complex phenotypes seen in these strains, since release of SDF-2 only occurs during culmination (2, 5). It appears that TagA and AcbA function in aggregates such that a single finger is produced and also to ensure proper cell type-specific gene expression during the slug stage. The excess ecmB-positive cells seen in tagAΔ and acbA− strains may be the result of precocious developmental timing, since ecmB is normally expressed in only a few anterior cells at the slug stage but in a much larger number of cells in the basal disc and lower cup of the fruiting body (18).

At our current stage of understanding, we can consider two hypotheses: (i) TagA is required in all cells for proper cell fate specification and it sets the conditions for proper AcbA signaling later in development, and (ii) proper cell fate specification requires that TagA process AcbA into SDF-2 (or some other peptide) and transports the product(s) across a membrane. The first hypothesis provides a more general model but still suggests that AcbA functions earlier than has been previously documented. Thus, early roles for SDF-2 and its receptor, DhkA, would have to be considered as the simplest way to explain AcbA's involvement in cell fate specification. The second hypothesis leads to specific predictions that are readily testable. Whether or not TagA and AcbA proteins interact directly as a processing enzyme/transporter and substrate will have to be addressed by cell biological and biochemical experiments. In either model, the terminal event may be the control of PKA activity through SDF-2 attenuation of DhkA signaling. There are several lines of evidence suggesting this as a viable model. First, SDF-2 is thought to attenuate constitutive signaling through the DhkA histidine kinase pathway, leading to elevated cyclic AMP levels and subsequent activation of PKA (4, 5, 17). Second, DhkA mRNA is expressed in prespore cells at 16 h of development and in all prestalk/stalk cell types of culminants and fruiting bodies (17). DhkA may well be expressed in all cells within aggregates, since its mRNA is dramatically up-regulated at 12 h of development, but this issue has not been examined directly. Finally, SDF-2 overproduction might be expected to reproduce defects similar to those observed in dhkA mutants. If TagA protease normally cleaves AcbA into SDF-2, overexpression of this protease may result in overproduction of SDF-2. The fact that acbA mutations suppress the TagA protease overexpression phenotypes lends some credence to this notion. Thus, it is interesting to note that TagA protease overexpression and DhkA null mutations both lead to excessive expression of ecmA in a cell-autonomous manner (7, 17). If the SDF-2/DhkA system is operating early in development we would expect the signaling to be intracellular, since wild-type cells do not rescue the cell specification phenotypes of tagA or acbA mutants.

The roles of AcbA, its subcellular localization, and the involvement of TagA are yet to be clearly delineated in biochemical terms at the finger and slug stages, but they appear to be fundamental to subsequent cell differentiation and morphogenesis. Although it seems likely that TagA and AcbA interact directly, there is currently no biochemical data to suggest the nature of this interaction. Based on the data presented, however, we can only speculate on the nature of the active factor that acts to specify cell fate. The misspecification of cell fate seen in the tagA1209 strain indicates that TagA transport function is vital to this process. We speculate that the multiple tips on aggregates and the excess of prestalk cells as judged by the ecmA/GFP marker in the tagA1209 mutant relative to the tagA deletion and acbA−/tagA1209 mutants is caused by proteolytic processing of AcbA by TagA in the absence of transport, resulting in a prestalk-like cell fate. However, it is not obvious that the processed form of AcbA required for cell fate specification early in development should be identical to SDF-2. Indeed, we have been unable to detect SDF-2 activity in cell lysates of developing cell aggregates or slugs (unpublished observations). Biochemical experiments aimed at directly addressing the issue of the potential enzymatic role of TagA in AcbA processing are the current focus of research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Danny Fuller for superb technical assistance.

This work was supported by USPHS grant GM52359 (to A.K.) and GM078175 (to W.F.L.) from the National Institutes of Health. M.C. was supported, in part, by an NIH Minority Student Development Grant (R25GM56929; G. Slaughter, P.I.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 October 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abele, R., and R. Tampe. 1999. Function of the transport complex TAP in cellular immune recognition. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1461:405-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anjard, C., W. T. Chang, J. Gross, and W. Nellen. 1998. Production and activity of spore differentiation factors (SDFs) in Dictyostelium. Development 125:4067-4075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anjard, C., and W. F. Loomis. 2006. GABA induces terminal differentiation of Dictyostelium through a GABAB receptor. Development 133:2253-2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anjard, C., and W. F. Loomis. 2005. Peptide signaling during terminal differentiation of Dictyostelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:7607-7611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anjard, C., C. Zeng, W. F. Loomis, and W. Nellen. 1998. Signal transduction pathways leading to spore differentiation in Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev. Biol. 193:146-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa, E., and A. Guidotti. 1991. Diazepam binding inhibitor (DBI): a peptide with multiple biological actions. Life Sci. 49:325-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Good, J. R., M. Cabral, S. Sharma, J. Yang, N. Van Driessche, C. A. Shaw, G. Shaulsky, and A. Kuspa. 2003. TagA, a putative serine protease/ABC transporter of Dictyostelium that is required for cell fate determination at the onset of development. Development 130:2953-2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Good, J. R., and A. Kuspa. 2000. Evidence that a cell-type-specific efflux pump regulates cell differentiation in Dictyostelium. Dev. Biol. 220:53-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knecht, D. A., S. M. Cohen, W. F. Loomis, and H. F. Lodish. 1986. Developmental regulation of Dictyostelium discoideum actin gene fusions carried on low-copy and high-copy transformation vectors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6:3973-3983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manstein, D. J., and D. M. Hunt. 1995. Overexpression of myosin motor domains in Dictyostelium: screening of transformants and purification of the affinity tagged protein. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 16:325-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrison, A., R. L. Blanton, M. Grimson, M. Fuchs, K. Williams, and J. Williams. 1994. Disruption of the gene encoding the EcmA, extracellular matrix protein of Dictyostelium alters slug morphology. Dev. Biol. 163:457-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puta, F., and C. Zeng. 1998. Blasticidin resistance cassette in symmetrical polylinkers for insertional inactivation of genes in Dictyostelium. Folia Biol. Prague 44:185-188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schjerling, C. K., R. Hummel, J. K. Hansen, C. Borsting, J. M. Mikkelsen, K. Kristiansen, and J. Knudsen. 1996. Disruption of the gene encoding the acyl-CoA-binding protein (ACB1) perturbs acyl-CoA metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 271:22514-22521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaulsky, G., A. Kuspa, and W. F. Loomis. 1995. A multidrug resistance transporter serine protease gene is required for prestalk specialization in Dictyostelium. Genes Dev. 9:1111-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaulsky, G., and W. F. Loomis. 1993. Cell type regulation in response to expression of ricin-A in Dictyostelium. Dev. Biol. 160:85-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sussman, M. 1987. Cultivation and synchronous morphogenesis of Dictyostelium under controlled experimental conditions, p. 9-29. In J. A. Spudich (ed.), Methods in cell biology, vol. 28. Academic Press, Orlando, FL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang, N., F. Soderbom, C. Anjard, G. Shaulsky, and W. F. Loomis. 1999. SDF-2 induction of terminal differentiation in Dictyostelium discoideum is mediated by the membrane-spanning sensor kinase DhkA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:4750-4756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams, J. 1997. Prestalk and stalk heterogeneity in Dictyostelium, p. 293-304. In Y. Maeda, K. Inouye, and I. Takeuchi (ed.), Dictyostelium - a model system for cell and developmental biology. Universal Academy Press, Tokyo, Japan.