Abstract

Using antibodies raised with chlamydial fusion proteins, we have localized a protein encoded by the hypothetical open reading frame Cpn0797 in the cytoplasm of Chlamydia pneumoniae-infected host cells. The anti-Cpn0797 antibodies specifically recognized Cpn0797 protein without cross-reacting with either CPAFcp or Cpn0796, the only two proteins known to be secreted into the host cell cytosol by C. pneumoniae organisms. Thus, Cpn0797 represents the third C. pneumoniae protein secreted into the host cell cytosol experimentally identified so far.

Chlamydia pneumoniae infects the human respiratory tract, leading to various airway symptoms, especially in immune-incompetent individuals (7, 17). Respiratory infection with C. pneumoniae is also associated with other health problems, including cardiovascular diseases (2, 3, 14-16, 18, 20). Like other chlamydial species, C. pneumoniae organisms have adapted an obligate intravacuolar life with a biphasic growth cycle (9, 10, 17). The ability to replicate inside the cytoplasmic vacuoles of host cells contributes to chlamydial pathogenicity (1, 17). The vacuole laden with chlamydial organisms is also called an inclusion. Although Chlamydia can accomplish its entire biosynthesis, particle assembly, and differentiation within the inclusion, it must exchange both materials and signals with host cells in order to establish and maintain intravacuolar growth. Chlamydia is not only able to import nutrients and metabolic intermediates from host cells (4, 11, 12, 19, 23), but also secretes chlamydial factors into host cells (5, 22, 24, 26). It has been hypothesized that Chlamydia can actively manipulate host signal pathways (6, 8, 22-24, 25) via its secreted factors. Indeed, a protein encoded by the hypothetical open reading frame (ORF) Cpn1016 in the C. pneumoniae genome (designated chlamydial protease/proteasome-like activity factor in C. pneumoniae [CPAFcp]) has been shown to degrade host transcription factors required for major histocompatibility complex gene activation (5, 13). More recently, it was reported that the N terminus, but not the C terminus, of another C. pneumoniae protein (designated Cpn0796n and Cpn0796c, respectively) encoded by the hypothetical ORF Cpn0796 was secreted into the host cell cytosol, although the biological significance of Cpn0796n secretion is still unclear (24). Since proteins secreted into the host cell cytosol may potentially function as effectors in C. pneumoniae interactions with host cells, searching for C. pneumoniae-secreted proteins has become a hot area under intensive investigation. We recently applied an anti-fusion protein antibody approach to search for C. pneumoniae proteins that are secreted into the host cell cytosol.

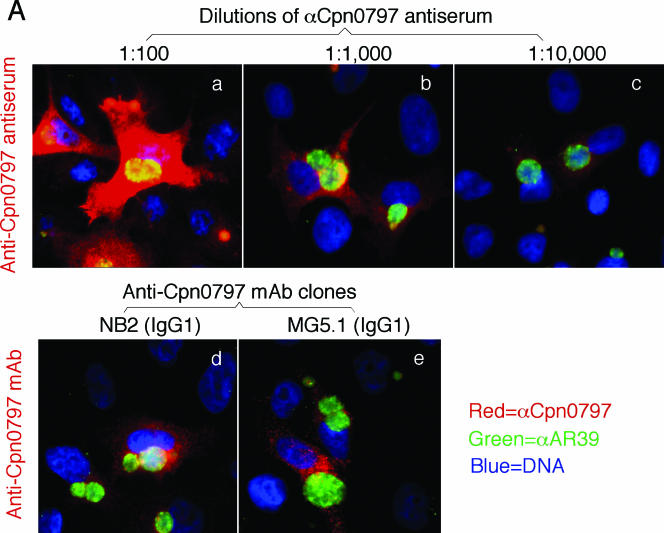

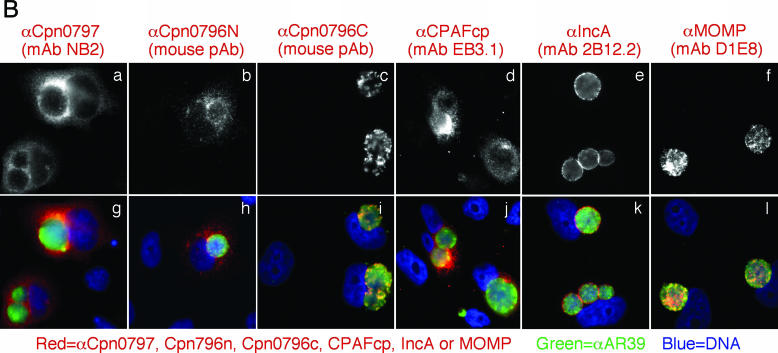

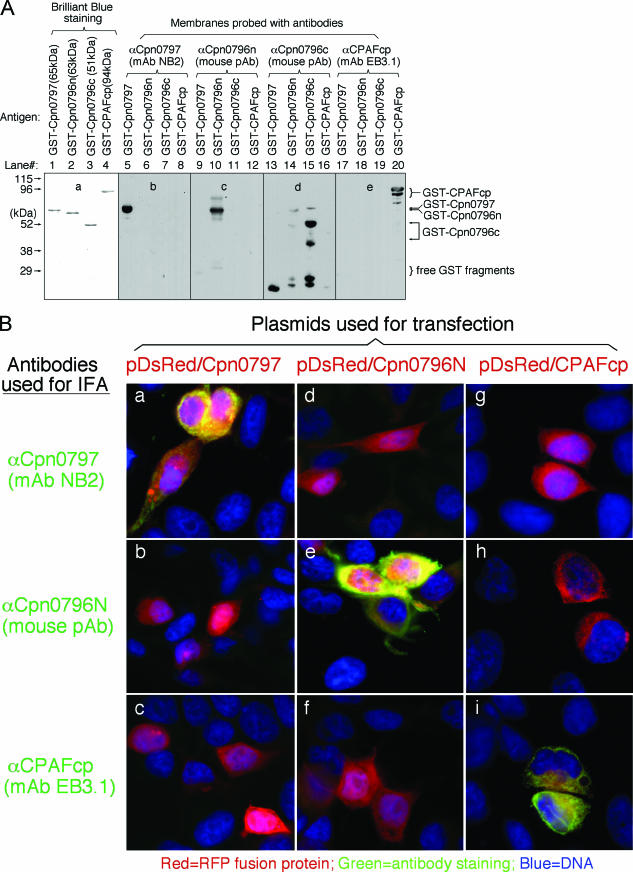

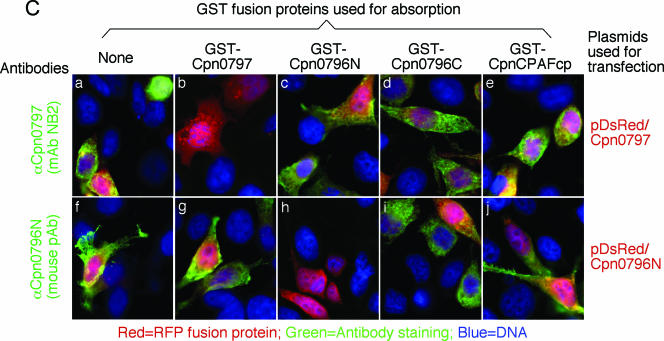

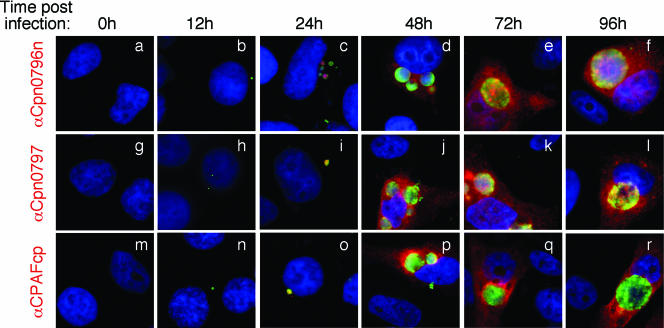

Proteins encoded by hypothetical ORFs from the C. pneumoniae AR39 genome were expressed as fusion proteins with glutathione S-transferase (GST) fused to the N terminus as described previously (21). Antibodies raised with the chlamydial fusion proteins were used to localize the endogenous proteins in C. pneumoniae-infected cells via an indirect immunofluorescence assay, as described elsewhere (26). A C. pneumoniae protein encoded by the hypothetical ORF Cpn0797 was detected in the cytoplasm of the C. pneumoniae-infected host cells (Fig. 1). Both the polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) raised with the GST-Cpn0797 fusion protein detected a dominant cytosolic signal similar to the signals revealed by the anti-CPAFcp and anti-Cpn0796n antibodies, but not the anti-Cpn0796c, anti-IncA (Cpn0186), and anti-MOMP antibodies. Since CPAFcp and Cpn0796n are the only two proteins previously shown to be secreted into the host cell cytosol by C. pneumoniae (5, 24), while Cpn0796c and MOMP are localized in the inclusion and IncA in the inclusion membrane, the above observations show that Cpn0797 is a new secreted protein. Several approaches were used to verify the antibody-staining specificities. The anti-Cpn0797 antibodies reacted with GST-Cpn0797 but not with the GST-CPAFcp, GST-Cpn0796n, or GST-Cpn0796c fusion protein, although all fusion proteins were loaded in equal amounts and detected by their corresponding homologous antibodies (Fig. 2A). The antibodies raised with the chlamydial GST fusion proteins were further reacted with the red fluorescent protein (RFP)-C. pneumoniae fusion proteins expressed in transfected cells (Fig. 2B). The anti-Cpn0797 antibody detected only RFP-Cpn0797 (Fig. 2B, a), but not the RFP-Cpn0796n (Fig. 2B, d) and RFP-CPAFcp (Fig. 2B, g) fusion proteins, while the anti-Cpn0796 and anti-CPAFcp antibodies recognized only their corresponding homologous RFP fusion proteins (e and i) without cross-reacting with the unrelated fusion proteins. The recognition of RFP-Cpn0797 by anti-Cpn0797 was blocked by GST-Cpn0797 (Fig. 2C, b), but not by the GST-Cpn0796n (Fig. 2C, c), GST-Cpn0796c (Fig. 2C, d), and GST-CPAFcp (Fig. 2C, e) fusion proteins. Conversely, binding of the anti-Cpn0796n antibody to RFP-Cpn0796n was blocked by GST-Cpn0796n (Fig. 2C, h), but not by the GST-Cpn0797, GST-Cpn0796c, and GST-CPAFcp fusion proteins. Most importantly, the detection of the endogenous antigens in the C. pneumoniae-infected cells by the anti-Cpn0797, anti-Cpn0796n, anti-Cpn0796c (Fig. 3A), and anti-CPAFcp (Fig. 3B) antibodies was blocked by the corresponding homologous, but not the heterologous, GST fusion proteins. Together, the above-mentioned experiments demonstrated that the anti-Cpn0797 antibody specifically detected the Cpn0797 antigen in the cytosol of the C. pneumoniae-infected cells. We have also used the Cpn0797-specific antibody to analyze the Cpn0797 protein expression pattern (Fig. 4). In this experiment, Cpn0797 and the other two secreted proteins, Cpn796n and CPAFcp, were simultaneously monitored during infection. All three proteins were first detected 24 h after infection (Fig. 4c, i, and o), and secretion of the proteins into the cytosol of the infected host cells became apparent 48 h after infection (Fig. 4d, j, and p). All three secreted proteins remained in the host cell cytosol throughout the rest of the infection cycle. Although CPAFcp is known to have a proteolytic activity that is able to degrade host transcriptional factors required for host defense (5, 26), it is not known what functions the secreted Cpn0797 and Cpn0796 proteins may have.

FIG.1.

Detection of Cpn0797 in C. pneumoniae-infected cells. HeLa cells were infected with C. pneumoniae AR39 organisms at a multiplicity of infection of 0.5 in the presence of 2 μg/ml of cycloheximide for 72 h. The infected cultures, grown on coverslips, were processed for staining with a mouse antiserum at various dilutions (A, a to c) and MAbs NB2 (A, d, and B, a and g) and MG5.1 (A, e), all of which were raised with the GST-Cpn0797 fusion protein. Other primary mouse antibodies included the mouse antisera to Cpn0796n (B, b and h) and Cpn0796c (B, c and i) and MAbs to CPAFcp (clone EB3.1) (B, d and j), IncA (clone 2B12.2) (B, e and k), and MOMP (clone GZD1E8) (B, f and l). The primary antibodies against Cpn0796, Cpn0797, and IncA were raised in this study, while the anti-CPAFcp and MOMP antibodies were previously described (5). The mouse antibody stains were visualized with a goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugated with Cy3 (red). The chlamydial organisms were visualized with a C. pneumoniae-specific rabbit antiserum plus a Cy2-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (green), while the DNA was stained with Hoechst (blue). Note that the anti-Cpn0797 antibodies detected strong cytosolic signals similar to those obtained with the anti-Cpn0796n and -CPAFcp antibodies, but not the other antibodies.

FIG.2.

Anti-Cpn0797 antibody detection of C. pneumoniae fusion proteins on nitrocellulose membranes (A) and in transfected cells (B and C). (A) In a Western blot assay, four GST fusion proteins (indicated as antigens at the top of each lane) were loaded onto sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels in equal amounts (as visualized with the total-protein-staining dye Coomassie brilliant blue [a]), and the gel-resolved protein bands were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane for reaction with the anti-fusion protein antibodies shown above the lanes. Note that the antibodies recognized only the corresponding homologous proteins without cross-reacting with unrelated protein bands. The anti-Cpn0796c serum also stained bands corresponding to the degraded GST-containing fragments derived from other fusion proteins, but without reacting with the unrelated full-length fusion proteins. (B) HeLa cells transfected with the recombinant plasmid pDsRed-C1 monomer/Cpn0797, Cpn0796N, or CPAFcp (expressed as RFP fusion proteins [red]) for 24 h were processed for immunostaining with various antibodies listed on the left (green) plus Hoechst (blue). It is clear that the antibodies labeled only the corresponding homologous gene-transfected cells without cross-reacting with unrelated gene-transfected cells. pAB, polyclonal antibody. (C) Both the anti-Cpn0797 MAb NB2 and anti-Cpn0796n antiserum were preabsorbed with the four GST fusion proteins, respectively, followed by immunostaining as described for panel B. The antibody preabsorption/depletion was carried out as previously described (26). Note that antibody staining was blocked only by preabsorption with the corresponding homologous GST fusion proteins.

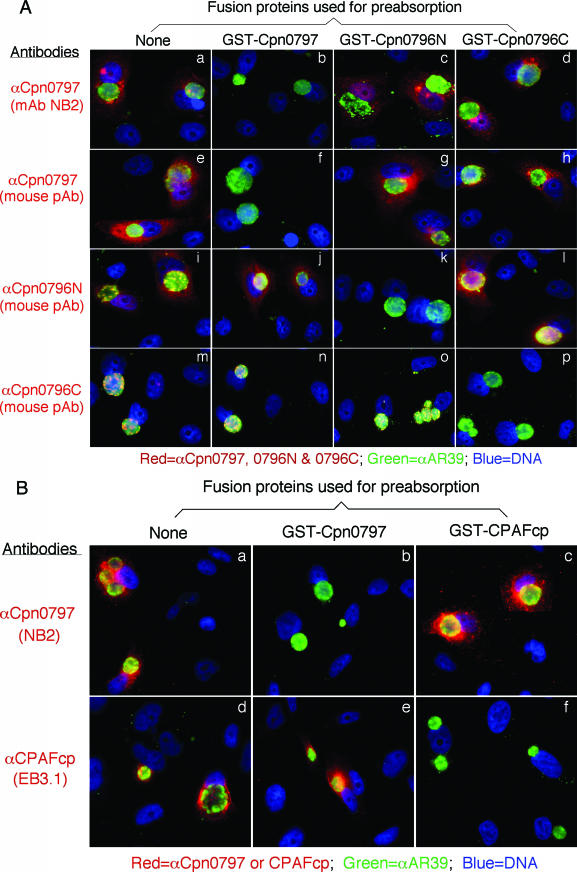

FIG. 3.

Detection of endogenous proteins in C. pneumoniae-infected cells with or without preabsorption of antibodies with GST fusion proteins. (A and B) C. pneumoniae-infected HeLa cells were processed for immunostaining as described in the legend to Fig. 1A, except that the C. pneumoniae protein-specific antibodies listed on the left were subjected to preabsorption with various GST fusion proteins, listed at the top, before the antibodies were applied to immunostaining. The antibody preabsorption/depletion was carried out as previously described (26). Note that the antibody labeling of endogenous antigens was blocked only by the corresponding homologous GST fusion proteins, but not the heterologous proteins. pAB, polyclonal antibody.

FIG. 4.

Monitoring Cpn0797, Cpn0796n, and CPAFcp protein expression during infection. The C. pneumoniae-infected culture samples obtained as described in the legend to Fig. 1 were processed at various times after infection (as indicated at the top) for immunofluorescence staining with the primary mouse antibodies anti-Cpn0796n (mouse polyclonal antibody), anti-Cpn0797 (mouse polyclonal antibody), and anti-CPAFcp (MAb EB3.1), respectively. The mouse antibody stains were visualized with a goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugated with Cy3 (red). The chlamydial organisms were visualized with a C. pneumoniae-specific rabbit antiserum plus a Cy2-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (green), while the DNA was stained with Hoechst (blue). Note that all three endogenous antigens became detectable 24 h after infection (c, i, and o) and were obviously secreted into the host cell cytosol 48 h after infection (d, j, and p).

The current study has not only confirmed a previous observation (24) that the Cpn0796 N-terminal fragment is secreted into the host cell cytosol while the C terminus is localized within the C. pneumoniae inclusion (Fig. 1B, b, c, h, and i, and 3A, i to l and m to p), but more importantly, it has identified the hypothetical protein Cpn0797 as a novel secreted protein using both polyclonal antisera and monoclonal antibodies. Although Cpn0797 shares 36% amino acid similarity with Cpn0796n (http://www.stdgen.lanl.gov), the anti-Cpn0797 and anti-Cpn0796n antibodies recognized only the corresponding antigens without cross-reacting with each other's antigens in Western blot (Fig. 2A) and immunofluorescence (Fig. 2B and 3A) assays. The anti-Cpn0797 and anti-CPAFcp antibodies also did not cross-react with each other's antigens (Fig. 2A and 3B). Therefore, Cpn0797 represents a third antigen secreted by C. pneumoniae into the host cell cytosol.

Both the Cpn0797 and Cpn0796 ORFs are in a gene cluster consisting of six hypothetical genes. All six hypothetical proteins share approximately 20 to 40% amino acid sequence homology with each other. The Cpn0796 ORF is the longest, encoding 674 amino acids, while the other five ORFs are about half the size, encoding 365 amino acids (Cpn0797) or less. Cpn0794, -0797, -0798, and -0799 are homologous to the N-terminal region of Cpn0796, while Cpn0795 is homologous to the C-terminal region of Cpn0796 (http://www.stdgen.lanl.gov; 24). The biological significance of this gene organization is not clear. However, it appears that ORFs Cpn0794 and Cpn0795 were derived from a single ORF and that Cpn0797, -0798, and -0799 have lost half of their downstream coding sequences, which is consistent with the concept that the chlamydial genome is evolutionarily shrinking. In general, what is preserved through evolution should serve biological functions. We report here that in addition to the Cpn0796 protein, Cpn0797 is also secreted into the cytosol of the C. pneumoniae-infected host cells, suggesting that these two hypothetical proteins may mediate chlamydial interactions with host cells. Efforts are under way to determine the precise locations of the other proteins encoded by genes in the same cluster.

Another interesting question is how Cpn0797 is secreted. An autotransporter model was proposed for the secretion of Cpn0796n (24). Cpn0797 also shares 37% amino acid sequence homology with the N terminus of an autotransporter beta-domain protein from Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/BLAST.cgi). These observations suggest that Cpn0797 may be secreted via a mechanism similar to an autotransporter. However, Cpn0797 is considerably shorter than the typical autotransporters, and a putative gram-negative signal sequence (from residues 1 to 32) has been identified at its N terminus (http://www.stdgen.lanl.gov), suggesting that Cpn0797 may also be secreted via an N-terminal signal sequence-dependent pathway. Coincidentally, the C. pneumoniae-secreted protein CPAFcp also contains a putative N-terminal signal sequence consisting of the first 20 amino acids (http://www.stdgen.lanl.gov/). We can reasonably speculate that the C. pneumoniae organisms may have evolved multiple means for exporting their proteins into the host cell cytosol. As more secreted proteins are identified, we will accumulate more tools for pinpointing the precise mechanisms by which these proteins are secreted and uncovering what these secreted proteins do in the host cell cytoplasm.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants (to G. Zhong) from the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Editor: F. C. Fang

REFERENCES

- 1.Campbell, L. A., and C. C. Kuo. 2002. Chlamydia pneumoniae pathogenesis. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:623-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell, L. A., and C. C. Kuo. 2004. Chlamydia pneumoniae—an infectious risk factor for atherosclerosis? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell, L. A., T. Nosaka, M. E. Rosenfeld, K. Yaraei, and C. C. Kuo. 2005. Tumor necrosis factor alpha plays a role in the acceleration of atherosclerosis by Chlamydia pneumoniae in mice. Infect. Immun. 73:3164-3165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carabeo, R. A., D. J. Mead, and T. Hackstadt. 2003. Golgi-dependent transport of cholesterol to the Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:6771-6776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan, P., F. Dong, Y. Huang, and G. Zhong. 2002. Chlamydia pneumoniae secretion of a protease-like activity factor for degrading host cell transcription factors is required for major histocompatibility complex antigen expression. Infect. Immun. 70:345-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan, T., H. Lu, H. Hu, L. Shi, G. A. McClarty, D. M. Nance, A. H. Greenberg, and G. Zhong. 1998. Inhibition of apoptosis in chlamydia-infected cells: blockade of mitochondrial cytochrome c release and caspase activation. J. Exp. Med. 187:487-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grayston, J. T. 1992. Chlamydia pneumoniae, strain TWAR pneumonia. Annu. Rev. Med. 43:317-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greene, W., Y. Xiao, Y. Huang, G. McClarty, and G. Zhong. 2004. Chlamydia-infected cells continue to undergo mitosis and resist induction of apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 72:451-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hackstadt, T. 1998. The diverse habitats of obligate intracellular parasites. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1:82-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hackstadt, T., E. R. Fischer, M. A. Scidmore, D. D. Rockey, and R. A. Heinzen. 1997. Origins and functions of the chlamydial inclusion. Trends Microbiol. 5:288-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hackstadt, T., D. D. Rockey, R. A. Heinzen, and M. A. Scidmore. 1996. Chlamydia trachomatis interrupts an exocytic pathway to acquire endogenously synthesized sphingomyelin in transit from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane. EMBO J. 15:964-977. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hackstadt, T., M. A. Scidmore, and D. D. Rockey. 1995. Lipid metabolism in Chlamydia trachomatis-infected cells: directed trafficking of Golgi-derived sphingolipids to the chlamydial inclusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:4877-4881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heuer, D., V. Brinkmann, T. F. Meyer, and A. J. Szczepek. 2003. Expression and translocation of chlamydial protease during acute and persistent infection of the epithelial HEp-2 cells with Chlamydophila (Chlamydia) pneumoniae. Cell Microbiol. 5:315-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu, H., G. N. Pierce, and G. Zhong. 1999. The atherogenic effects of chlamydia are dependent on serum cholesterol and specific to Chlamydia pneumoniae. J. Clin. Investig. 103:747-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo, C. C., L. A. Campbell, and M. E. Rosenfeld. 2002. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and atherosclerosis: methodological considerations. Circulation 105:e34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuo, C. C., J. T. Grayston, L. A. Campbell, Y. A. Goo, R. W. Wissler, and E. P. Benditt. 1995. Chlamydia pneumoniae (TWAR) in coronary arteries of young adults (15-34 years old). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:6911-6914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuo, C. C., L. A. Jackson, L. A. Campbell, and J. T. Grayston. 1995. Chlamydia pneumoniae (TWAR). Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:451-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu, L., H. Hu, H. Ji, A. D. Murdin, G. N. Pierce, and G. Zhong. 2000. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection significantly exacerbates aortic atherosclerosis in an LDLR−/− mouse model within six months. Mol. Cell Biochem. 215:123-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scidmore, M. A., E. R. Fischer, and T. Hackstadt. 1996. Sphingolipids and glycoproteins are differentially trafficked to the Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion. J. Cell Biol. 134:363-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma, J., Y. Niu, J. Ge, G. N. Pierce, and G. Zhong. 2004. Heat-inactivated C. pneumoniae organisms are not atherogenic. Mol. Cell Biochem. 260:147-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma, J., Y. Zhong, F. Dong, J. M. Piper, G. Wang, and G. Zhong. 2006. Profiling of human antibody responses to Chlamydia trachomatis urogenital tract infection using microplates arrayed with 156 chlamydial fusion proteins. Infect. Immun. 74:1490-1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaw, A. C., B. B. Vandahl, M. R. Larsen, P. Roepstorff, K. Gevaert, J. Vandekerckhove, G. Christiansen, and S. Birkelund. 2002. Characterization of a secreted Chlamydia protease. Cell Microbiol. 4:411-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su, H., G. McClarty, F. Dong, G. M. Hatch, Z. K. Pan, and G. Zhong. 2004. Activation of Raf/MEK/ERK/cPLA2 signaling pathway is essential for chlamydial acquisition of host glycerophospholipids. J. Biol. Chem. 279:9409-9416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vandahl, B. B., A. Stensballe, P. Roepstorff, G. Christiansen, and S. Birkelund. 2005. Secretion of Cpn0796 from Chlamydia pneumoniae into the host cell cytoplasm by an autotransporter mechanism. Cell Microbiol. 7:825-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiao, Y., Y. Zhong, W. Greene, F. Dong, and G. Zhong. 2004. Chlamydia trachomatis infection inhibits both Bax and Bak activation induced by staurosporine. Infect. Immun. 72:5470-5474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhong, G., P. Fan, H. Ji, F. Dong, and Y. Huang. 2001. Identification of a chlamydial protease-like activity factor responsible for the degradation of host transcription factors. J. Exp. Med. 193:935-942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]