Abstract

Objectives To describe the course of acute low back pain and sciatica and to identify clinically important prognostic factors for these conditions.

Design Systematic review.

Data sources Searches of Medline, Embase, Cinahl, and Science Citation Index and iterative searches of bibliographies.

Main outcome measures Pain, disability, and return to work.

Results 15 studies of variable methodological quality were included. Rapid improvements in pain (mean reduction 58% of initial scores), disability (58%), and return to work (82% of those initially off work) occurred in one month. Further improvement was apparent until about three months. Thereafter levels for pain, disability, and return to work remained almost constant. 73% of patients had at least one recurrence within 12 months.

Conclusions People with acute low back pain and associated disability usually improve rapidly within weeks. None the less, pain and disability are typically ongoing, and recurrences are common.

Introduction

Clinical practice guidelines promote the view that acute low back pain has a favourable prognosis—the 2000 UK guideline states that “90% [of cases] will recover within six weeks.”1,2 Yet these estimates are either unsubstantiated or based on individual studies. To date evidence of the prognosis of acute low back pain has not been systematically reviewed.

Many guidelines for acute low back pain advocate identification of adverse prognostic factors such as fear avoidance behaviours, leg pain, or low job satisfaction. Previous reviews of prognostic factors have been descriptive, do not use strict inception cohorts, or do not provide quantitative information of the predictive value of the factors.3-6

We aimed to systematically review published data on the course of acute low back pain and to identify clinically important prognostic factors. The term course refers to both the natural course and the clinical course of low back pain.

Methods

To be included studies had to be of a prospective design, describe the source of participants and method of sampling, have an inception cohort of participants with low back pain or sciatica for less than three weeks, have a follow up period of at least three months, and report on symptoms, health related quality of life, disability, or return to work. Studies were excluded that recruited patients with specific diseases such as arthritis, fracture, tumour, or cauda equina syndrome (but not sciatica).

Identification of studies and assessment of methodological quality

Studies were identified through searches of Medline, Embase, and Cinahl to March 2002. We also searched personal files and tracked references of included studies through the Science Citation Index. The search strategies were those recommended by the Cochrane Back Review Group together with a strategy for searching Medline for prognostic studies.7,8 Keywords used were inception, survival, logistic, Cox, life tables, and log rank. We had no language restrictions.

Despite there being no widely accepted method for assessing methodological quality of prognosis studies and no empirical evidence of bias related to various methodological features of such studies, validity criteria have been proposed.8 Methodological quality was assessed by six criteria (table 1). Two raters independently assessed the quality. A third reviewer resolved disagreements.

Table 1.

Assessment of methodological quality of studies detailing course of acute low back pain

| Study | Defined sample* | Representative sample† | Complete follow up‡ | Prognosis§ | Blinded outcome¶ | Statistical adjustment** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooper et al 199612; Tate et al 199913 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Coste et al 199414 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Dettori et al 199515 | Yes | No | No | Yes | NA | NA |

| Faas et al 199316; Faas et al 199517 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | NA |

| Fordyce et al 198618 | Yes | No | No | No | NA | NA |

| Hazard et al 199619; Reid et al 199720 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Hazard et al 200021 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | NA |

| Hides et al 199422; Hides et al 200123 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | NA |

| Klenerman et al 199524 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Malmivaara et al 199525 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | NA |

| Rozenberg et al 200226 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | NA |

| Schiottz-Christensen et al 199927 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Seferlis et al 19989; Seferlis et al28 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Sieben et al 200229 | Yes | No | No | Yes | NA | NA |

| Weber et al 199330 | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | NA |

No-criterion clearly not satisfied or unclear if criterion is satisfied. NA=study did not evaluate prognostic factors.

Description of source of participants and inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Participants selected by random selection or as consecutive cases.

At least one prognostic outcome available from at least 80% of study population at three month follow up or later.

Studies must provide raw data, percentages, survival rates, or continuous outcomes.

Assessor unaware of at least one prognostic factor, used to predict prognostic outcome, at time prognostic outcome was measured.

For at least two prognostic factors with adjustment factor reported.

Data extraction and analysis

Study characteristics extracted from eligible papers were target population, sample size, duration of low back pain at time of enrolment, description of interventions, duration of follow up, prognostic factors, and outcome measures. Outcome data extracted were pain, disability, return to work, and recurrences. Data were extracted for time points where follow up was at least 80%. Data on return to work were obtained from the stratum of participants off work at baseline. To facilitate comparison, pain and disability scores were converted to a 100 point scale. Ten studies were controlled trials. For these studies, data were extracted for the control group, defined as the group receiving the least active intervention. In one trial, outcomes were reported only for the whole study sample because at follow up no differences were found between the groups receiving manual therapy, intensive training, or medical care.9 Prognostic data from this study are therefore based on the outcomes of the three groups.

The Wilson score method was used to calculate the confidence intervals for a single proportion.10 When it was possible to pool data across studies we obtained n weighted pooled means for continuous data and variance weighted pooled proportions for dichotomous data. The n weighted mean was used in preference to the variance weighted mean (the usual method of meta-analysis) because several studies did not provide variance data. Variance weighted pooled proportions were calculated using a random effects model.11

Studies evaluating prognostic factors used a range of modelling procedures and many different covariates, making pooling across studies problematic.8 Prognostic data were therefore not pooled. Data on prognostic factors were extracted only if the study reported on at least 80% of participants. If possible, odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were extracted or calculated from the data. A second reviewer checked the data extraction.

Results

The search retrieved 4458 articles, of which only 159,12-30 fulfilled all inclusion criteria and were included in our review (table 2). Five studies were described in more than one report.9,12,13,16,17,19,20,22,23,28 Of the 15 studies, only one monitored patients with sciatica.30 The studies included nine randomised controlled trials that evaluated exercise,9,15,16,18,22,23,25,28 manual therapy,9,28 an educational pamphlet,21 medical care,9,16,22,23,28 non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,30 and bed rest25,26; one controlled trial that evaluated an early intervention in the work-place 12,13; and five cohort studies,14,19,20,24,27,29 one of which included an intervention by general practitioners.14 Patients were recruited from primary care,9,14,16,18,24,26-30 specialists,18,26 hospital emergency departments,9,15,18,22,23,28 and occupational healthcare providers.9,12,13,19-21,25,28,30

Table 2.

Description of included studies on acute low back pain

| Study | Participants (setting) | Design | Outcomes | Follow up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooper et al 199612; Tate et al 199913 | 218 nurses with occupational back injuries for <2 days (Canada) | Controlled trial comparing early intervention with control* (nill) | Pain (0-100; n=158), disability (Oswestry; n=158), and time loss from work (n=218) | 6 months |

| Coste et al 199414 | 103 patients with low back pain for <72 hours, consulting general practitioner (France) | Cohort study, with intervention by general practitioner | Pain (visual analogue scale), disability (French version of Roland Morris), time spent in bed, date of recovery, return to work | 8, 15, 30, 60, and 90 days |

| Dettori et al 199515 | 170 army employees with low back pain for <7 days presenting to army hospital (Germany) | Randomised controlled trial comparing flexion exercises, extension exercises, and control* (ice pack) | Pain (0-5), disability (Roland Morris), ability to return to full work, spinal mobility, satisfaction with care, recurrences | 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks and 12 months |

| Faas et al 199316; Faas et al 199517 | 473 patients with low back pain for <3 weeks, consulting general practitioner (Netherlands) | Randomised controlled trial comparing exercise, medical care, and placebo ultrasonography* | Pain (0-85), functional health status (Nottingham health profile), recurrences, medical care usage, days off work | 3 and 12 months |

| Fordyce et al 198618 | 107 patients with low back pain for <10 days, consulting general practitioner, emergency room, or orthopaedic clinics (United States) | Randomised controlled trial comparing exercises on pain contingent basis with exercises on time contingent basis | Sick or well score (composite score of work status, medical care usage, claims of impairment, pain drawings), activity levels, activities engaged in (activity pattern indicator) | 6 weeks and 12 months |

| Hazard et al 199619; Reid et al 199720 | 207 workers reporting occupational back injury within 11 days (United States) | Cohort study | Work status | 3 months |

| Hazard et al 200021 | 489 workers reporting occupational back injury within 11 days (United States) | Randomised controlled trial comparing educational pamphlet with control* (nil) | Work status, days off work | 3 and 6 months |

| Hides et al 199422; Hides et al 200123 | 41 patients with low back pain for <3 weeks presenting to emergency room (Australia) | Randomised controlled trial comparing stabilising exercises with medical care* | Pain (visual analogue scale), disability (Roland Morris), range of motion, activity, muscle atrophy, recurrences | 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks and 1 and 3 years |

| Klenerman et al 199524 | 300 patients with low back pain for <1 week, consulting general practitioner (United Kingdom) | Cohort study | Pain (0-10), disability (Oswestry) | 2 and 12 months |

| Malmivaara et al 199525 | 186 workers with low back pain for <3 weeks, consulting for occupational health care (Finland) | Randomised controlled trial comparing exercise, bed rest, and advice* | Pain (0-10), disability (Oswestry), sick days, health related quality of life (0-1), range of motion | 3 and 12 weeks |

| Rozenberg et al 200226 | 281 patients with low back pain for <72 hours, consulting general practitioner or rheumatologist (France) | Randomised controlled trial comparing bed rest with normal activity* | Pain (0-10), disability (Roland Morris), sick days, intensity of vertebral stiffness (Schober's test), recurrences | Day 6 or 7 and 1 and 3 months |

| Schiottz-Christensen et al 199927 | 524 patients with low back pain for <2 weeks, consulting general practitioner (Denmark) | Cohort study | Sick leave, sick days, functional recovery, complete recovery | 1, 6, and 12 months |

| Seferlis et al 19989; Seferlis et al 200028 | 180 patients with low back pain for <14 days, referred from general practitioner, occupational doctor, or emergency room (Sweden) | Randomised controlled trial comparing manual therapy, intensive training, and medical care*† | Pain (1-11), disability (Oswestry), physical examination, recurrences, sick leave | 1, 3, and 12 months |

| Sieben et al 200229 | 44 patients with low back pain for <2 weeks consulting general practitioner (Netherlands) | Cohort study | Pain (0-10), disability (Dutch version of Roland Morris), fear of movement (Tampa), thoughts about pain (Dutch version of pain catastrophising scale) | 3 and 12 months |

| Weber et al 199330 | 214 patients with sciatica for <14 days, referred by general practitioner or occupational doctor (Norway) | Randomised controlled trial comparing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (piroxicam) with placebo* | Pain (0-100), disability (Roland Morris), sick leave | 3 and 12 months |

Considered as control group for data extraction.

Outcomes were reported for whole study sample, so prognostic data based on outcomes of three groups.

Methodological quality

The two reviewers scored 84 quality criteria and agreed on 64 (76%). The intraclass correlation coefficient (2,1) for the total score was 0.52. Most studies defined the sample (87%). Five studies (33%) explicitly described methods for assembling a representative sample. Eleven studies (73%) had follow up of at least 80%. All but one study quantified prognosis.18 Six studies reported prognostic factors. Of the six studies, one (17%)19,20 used blinded assessment and four (67%)13,14,27,28 performed statistical adjustment for prognostic factors.

Course of low back pain

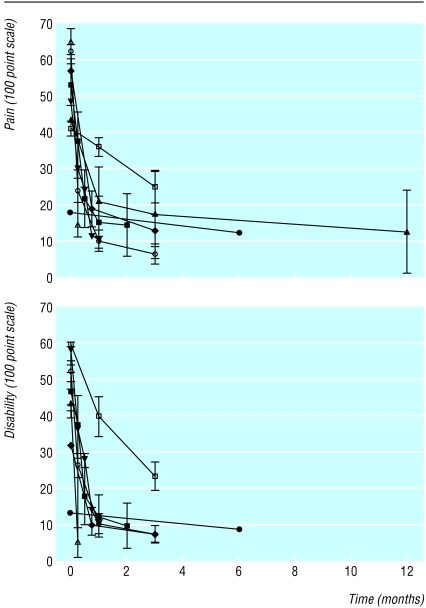

Most studies reported that pain decreased rapidly (by between 12% and 84% of initial levels, pooled mean 58%) within one month. Pain continued to decrease, albeit more slowly, until about three months (fig 1). Two studies that provided data beyond the three month follow up showed that pain levels remained nearly constant until the 12 month follow up.12,16 The pooled mean level of pain on a 100 point scale was 22 at one month and 15 between three and 12 months. A similar trend was seen for disability, which decreased by between 33% and 83% of initial levels (pooled mean 58%) within one month (fig 1). One study reported data on six month follow up.12 The pooled mean level of disability on a 100 point scale was 24 at one month and 14 between three and six months.

Fig 1.

Means (95% confidence intervals) for pain (top) and disability (bottom) during 12 months after onset of acute low back pain

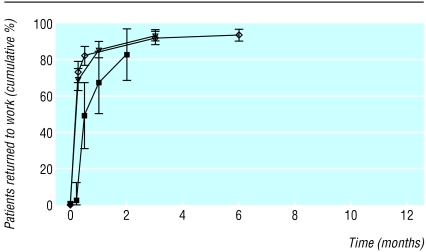

Between 68% and 86% of participants initially off work returned to work within one month (pooled estimate 82%, 95% confidence interval 73% to 91%; fig 2). One study reported data on six month follow up.21 The pooled estimate of the proportion of participants who returned to work, extracted from studies that reported return to work at three to six months, was 93% (91% to 96%).

Fig 2.

Means (95% confidence intervals) for return to work during 12 months after onset of acute low back pain of those initially off work. Reid et al20 report proportion returned to work, including those who returned to work and subsequently left work

The cumulative risk (one study, 135 participants) of at least one recurrence within three months was 26% (19% to 34%).26 Two studies reported recurrences within 12 months.16,23 The cumulative risk of at least one recurrence within 12 months varied from 66% to 84% (pooled estimate 73%, 59% to 88%). One study reported a cumulative risk of recurrence after three years of 84%.23

One study included patients with sciatica.30 In this sample, both back pain and leg pain decreased, on average, by 69% of initial scores within one month. Disability decreased by 57% of initial scores within one month. Data on long term pain and disability were not available.

Prognostic factors

Three studies reported on prognostic factors for at least 80% of the population.14,19,27 With one exception, odds ratios of significant prognostic factors ranged from 0.04 to 10.4. One study reported that scores of 0.48 or more on the Vermont disability prediction questionnaire were predictive of return to work at three months (odds ratio 76.3, 9.6 to 604.9; positive likelihood ratio 5.7, 3.9 to 8.5; negative likelihood ratio 0.07, 0.01 to 0.50).19

Discussion

Our review confirms the widely held view that most people with acute low back pain have rapid improvements in pain and disability within one month. Most of those off work with back pain also returned to work within one month. Further improvement occurred until about three months. Thereafter levels of pain, disability, and return to work remained almost constant, although only two studies provided follow up data beyond three months.12,16

Although most people return to work within 12 months, low levels of pain and disability persist. The studies did not report enough data to establish if levels of long term pain and disability reflect a small subgroup with high levels of pain and disability or a large subgroup with low levels of pain and disability. Nor is it clear whether chronic low levels of pain and disability are due to persistence of the original episode or to recurrent episodes.

Findings from previous reviews on prognostic factors of low back pain have been inconsistent.3-6 Putative prognostic factors include psychological factors such as distress,3,5 personal factors such as previous back pain,6 and work related factors such as job satisfaction.4 However, the evidence of the prognostic value of these factors comes mainly from studies that either did not recruit a relevant cohort or were methodologically weak. We located only one relevant, methodologically strong paper that provided evidence of a clinically useful predictor of outcome (in this case return to work) for primary care patients with acute low back pain. Hazard et al reported that scores of 0.48 or more on the Vermont disability prediction questionnaire were associated with a likelihood ratio of 5.7 and scores of less than 0.48 were associated with a likelihood ratio of 0.07.19 Given the low prevalence of failure to return to work at three months (pooled estimate of 6%), this predictor may be of limited clinical utility. Moreover, the cut-off score of 0.48 was chosen by inspection of the data, which is known to inflate predictive accuracy.31

What is already known on this topic

Clinical practice guidelines state that recovery from acute low back pain is rapid and complete

What this study adds

People with acute back pain experience improvements in pain, disability, and return to work within one month

Further but smaller improvements occur up to three months, after which pain and disability levels remain almost constant

Low levels of pain and disability persist from three to at least 12 months

Most people will have at least one recurrence within 12 months

Participants off work with low back pain have higher pain and disability scores than people who are working.32 Thus it may be sensible to consider separately the prognosis of those off work. It remains unclear if the prognosis of participants initially off work is worse than those who are not.

We included only studies that recruited inception cohorts of participants with low back pain or sciatica for less than three weeks. This policy may be sufficiently restrictive or too restrictive. A formal sensitivity analysis of participants with low back pain for less than one week and for less than three weeks showed that the reduction in pain and disability is similar in these two groups, justifying inclusion of studies with participants having pain for up to three weeks. However, inclusion of participants with low back pain for up to six weeks seems unjustified. Our data show that study participants had rapid improvements in pain and disability within one month. By six weeks, participants had already improved significantly; typically pain and disability were only a third of initial values. Moreover, many people no longer had back pain at six weeks, so those recruited with back pain for six weeks cannot be representative of all people who have back pain. We therefore believe it is justifiable to restrict our review to participants with low back pain for three weeks or less.

Contributors: LHMP designed the study protocol, located and selected studies, extracted and interpreted the data, wrote the paper, and approved the final manuscript. RDH designed the study protocol, extracted and interpreted the data, advised on the statistical analysis, and revised and approved the final manuscript. CGM and KMR designed the study protocol, assessed the quality of the trials, interpreted the data, and revised and approved the final manuscript. LHMP will act as guarantor for the paper.

Funding: LHMP's scholarship was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Australasian Physiotherapy Low Back Pain Trial Consortium. The guarantor accepts full responsibility for the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Koes BW, Van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Burton KA, Waddell G. Clinical guidelines for the management of low back pain in primary care: an international comparison. Spine 2001;26: 2504-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waddell G, Burton AK. Occupational health guidelines for the management of low back pain at work—evidence review. London: Faculty of Occupational Medicine, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Gatchel RJ, Gardea MA. Psychosocial issues: their importance in predicting disability, response to treatment, and search for compensation. Neurol Clin 1999;17: 149-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linton SJ. Occupational psychological factors increase the risk of back pain: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil 2001;11: 53-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pincus T, Burton AK, Vogel S, Field AP. A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine 2002;27: E109-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaw WS, Pransky G, Fitzgerald TE. Early prognosis for low back disability: intervention strategies for health care providers. Disabil Rehabil 2001;23: 815-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Tulder MW, Assendelft WJ, Koes BW, Bouter LM. Method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group for Spinal Disorders. Spine 1997;22: 2323-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altman DG. Systematic reviews of evaluations of prognostic variables. BMJ 2001;323: 224-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seferlis T, Nemeth G, Carlsson AM, Gillstrom P. Conservative treatment in patients sick-listed for acute low-back pain: a prospective randomised study with 12 months' follow-up. Eur Spine J 1998;7: 461-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newcombe RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med 1998;17: 857-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7: 177-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper JE, Tate RB, Yassi A, Khokhar J. Effect of an early intervention program on the relationship between subjective pain and disability measures in nurses with low back injury. Spine 1996;21: 2329-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tate RB, Yassi A, Cooper J. Predictors of time loss after back injury in nurses. Spine 1999;24: 1930-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coste J, Delecoeuillerie G, Cohen de Lara A, Le Parc JM, Paolaggi JB. Clinical course and prognostic factors in acute low back pain: an inception cohort study in primary care practice. BMJ 1994;308: 577-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dettori JR, Bullock SH, Sutlive TG, Franklin RJ, Patience T. The effects of spinal flexion and extension exercises and their associated postures in patients with acute low back pain. Spine 1995;20: 2303-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faas A, Chavannes AW, van Eijk JT, Gubbels JW. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exercise therapy in patients with acute low back pain. Spine 1993;18: 1388-95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faas A, van Eijk JT, Chavannes AW, Gubbels JW. A randomized trial of exercise therapy in patients with acute low back pain. Efficacy on sickness absence. Spine 1995;20: 941-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fordyce WE, Brockway JA, Bergman JA, Spengler D. Acute back pain: a control-group comparison of behavioral vs traditional management methods. J Behav Med 1986;9: 127-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hazard RG, Haugh LD, Reid S, Preble JB, MacDonald L. Early prediction of chronic disability after occupational low back injury. Spine 1996;21: 945-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reid S, Haugh LD, Hazard RG, Tripathi M. Occupational low back pain: Recovery curves and factors associated with disability. J Occup Rehabil 1997;7: 1-14. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazard RG, Reid S, Haugh LD, McFarlane G. A controlled trial of an educational pamphlet to prevent disability after occupational low back injury. Spine 2000;25: 1419-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hides JA, Stokes MJ, Saide M, Jull GA, Cooper DH. Evidence of lumbar multifidus muscle wasting ipsilateral to symptoms in patients with acute/subacute low back pain. Spine 1994;19: 165-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hides JA, Jull GA, Richardson CA. Long-term effects of specific stabilizing exercises for first-episode low back pain. Spine 2001;26: E243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klenerman L, Slade PD, Stanley IM, Pennie B, Reilly JP, Atchison LE, et al. The prediction of chronicity in patients with an acute attack of low back pain in a general practice setting. Spine 1995;20: 478-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malmivaara A, Hakkinen U, Aro T, Heinrichs ML, Koskenniemi L, Kuosma E, et al. The treatment of acute low back pain—bed rest, exercises, or ordinary activity? N Engl J Med 1995;332: 351-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rozenberg S, Delval C, Rezvani Y, Olivieri-Apicella N, Kuntz JL, Legrand E, et al. Bed rest or normal activity for patients with acute low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine 2002;27: 1487-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schiottz-Christensen B, Nielsen GL, Hansen VK, Schodt T, Sorensen HT, Olesen F. Long-term prognosis of acute low back pain in patients seen in general practice: a 1-year prospective follow-up study. Fam Pract 1999;16: 223-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seferlis T, Nemeth G, Carlsson AM. Prediction of functional disability, recurrences, and chronicity after 1 year in 180 patients who required sick leave for acute low-back pain. J Spinal Disord 2000;13: 470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sieben JM, Vlaeyen JW, Tuerlinckx S, Portegijs PJ. Pain-related fear in acute low back pain: the first two weeks of a new episode. Eur J Pain 2002;6: 229-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weber H, Holme I, Amlie E. The natural course of acute sciatica with nerve root symptoms in a double-blind placebo-controlled trial evaluating the effect of piroxicam. Spine 1993;18: 1433-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altman DG, Lausen B, Sauerbrei W, Schumacher M. Dangers of using “optimal” cutpoints in the evaluation of prognostic factors. J Natl Cancer Inst 1994;86: 829-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Truchon MFL. Biopsychosocial determinants of chronic disability and low-back pain: a review. J Occup Rehabil 2000;10: 117-42. [Google Scholar]