Abstract

Background. Multifocal osteosarcoma is usually described as the occurrence of the tumour at two or more sites in a patient without pulmonary metastases and may be synchronous or metachronous. Case report. A previously well 21-year old male, who presented with a swollen, painful right knee with no history of trauma, was found to have a high-grade osteosarcoma of the distal tibia and proximal femur. He underwent resection and prosthetic replacement of the distal femur and proximal tibia and remains well 19 months after diagnosis. Discussion. Multifocal osteosarcoma is a rare condition with a poor prognosis. There is debate about whether it represents multiple primary tumours or metastatic disease.

BACKGROUND

Multifocal or multicentric osteosarcoma was first described by Silverman [1]. It is usually defined as the occurrence of the tumour at two or more sites in a patient without pulmonary metastases [2–4] and may be synchronous (more than one lesion at presentation) or metachronous (new tumours developing after the initial treatment). We present here a case of synchronous multifocal osteosarcoma with an unusual management dilemma and review of the literature.

CASE REPORT

The patient was a fit and well 21-year old man who initially presented to his GP with a painful right knee with no history of trauma. This was diagnosed as a soft tissue injury, but, six months later, he noticed a swelling in his right proximal tibia. A plain x-ray showed a pathological fracture of the proximal tibia (Figure 1) and he was referred to the regional sarcoma centre via his local fracture clinic.

Figure 1.

Pathological fracture of right proximal tibia.

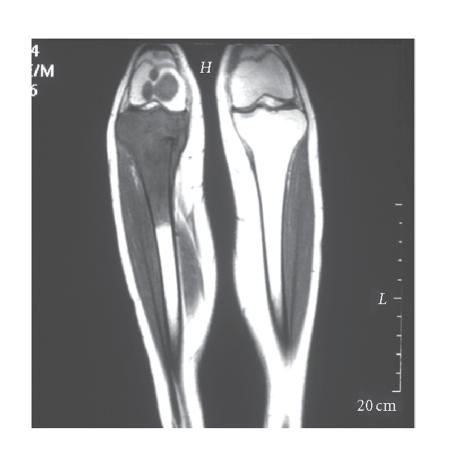

His initial investigations of blood tests, chest x-ray, and abdominal ultrasound showed no abnormalities, but MRI right knee clearly demonstrated an osteosarcoma in the proximal tibia with further lesions in the distal femur (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

MRI right leg, showing osteosarcoma of proximal tibia with further lesions in the distal femur.

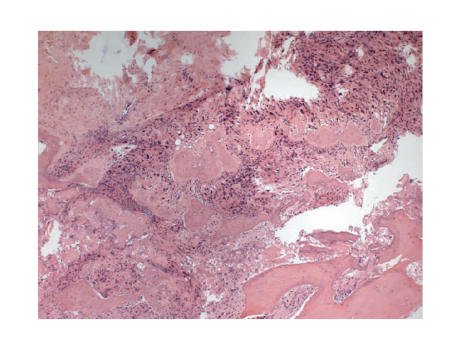

A biopsy of the proximal tibial lesion confirmed the diagnosis of high-grade intramedullary osteosarcoma (Figure 3). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy of five cycles of doxorubicin and cisplatin was commenced.

Figure 3.

Biopsy of proximal femoral lesion showing high-grade intramedullary osteosarcoma.

The preoperative CT chest was clear and a further biopsy of both the distal tibial and proximal femoral lesions confirmed high-grade intramedullary osteosarcoma with necrosis. Because of this good response to chemotherapy, the decision was made to conserve the leg. Therefore, six months after diagnosis, the patient underwent resection of the right proximal tibia and distal femur with prosthetic replacement (Figure 4). The final histology showed necrotic bone tumour in the femoral and tibial lesions.

Figure 4.

Postoperative x-rays showing prosthetic replacement.

The patient underwent three months of postoperative chemotherapy and he remains clinically well. Nine months later, he was walking unaided and with knee flexion in excess of 90 degrees. There are no radiological signs of recurrence, either on plain x-ray or on MRI. A further MRI scan is planned shortly.

DISCUSSION

Synchronous multifocal osteosarcoma is a rare condition, with a reported incidence of 1% to 3% [5–7]. There is much debate in the literature on whether it represents multiple primary tumours or metastatic disease. Initially, the case for multiple primary tumours was favoured [8, 9], because there was no obvious route for spread if the lungs were free of tumour, which was thought to rule out haematogenous metastasis. More recently, the report of cases related to p53 mutations [10] and retinoblastoma [11] might suggest a possible mechanism for multiple primary tumours.

However, more recent reviews conclude that the case for multicentric osteosarcoma as a metastatic process is almost proven [2, 12]. The reasons for this include the presence of a large “dominant” lesion, usually that leading to presentation, as in our case, which could be the primary tumour. Enneking and Kagan [13] suggest that bone-to-bone metastases could occur via a similar mechanism to that of prostate cancer via Batson's venous plexus [14], or intraosseous embolisation through marrow sinusoids. Alternatively, Hatori et al have demonstrated lymphatic spread to the lungs, giving another possible route [15]. It has also been noted that early case reports may well have underestimated the incidence of pulmonary metastasis, as the diagnosis of these relied on x-ray only, rather than CT scan [4]. Finally, there has been a correlation demonstrated between the responses of the dominant and other lesions to chemotherapy, which again points to a primary tumour and metastases [16].

The most commonly quoted classification is that of Amstutz [3], in which types I and II are synchronous (child/adolescent high grade and adult low grade, resp) and type III metachronous (subdivided into IIIa and b—early and late). Mahoney suggested a similar four-category system (A to D) ten years later [17]. They agree that the prognosis for synchronous multifocal osteosarcoma is poor, with mean survival of six months for type I/A and a slightly better range of 5 to 72 months for type II/B. Unfortunately, despite advances in both surgery and chemotherapy, more recent reports do not suggest a more favourable prognosis [7, 16, 18], with a mean survival of 27 months found by Bacci et al, although one patient was disease-free at nine years [16].

So what does this mean for our case? His has been a fairly standard course so far, although it could be argued that the pathological fracture predisposed to his multifocal presentation via either the venous or sinusoid routes. He remains alive and disease-free 19 months after diagnosis and will hopefully be one of the few who stays that way.

References

- 1.Silverman G. Multiple osteogenic sarcoma. Archives of Pathology. 1936;21:88–95. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daffner RH, Kennedy SL, Fox KR, Crowley JJ, Sauser DD, Cooperstein LA. Synchronous multicentric osteosarcoma: the case for metastases. Skeletal Radiology. 1997;26(10):569–578. doi: 10.1007/s002560050289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amstutz HC. Multiple osteogenic sarcomata - metastatic or multicentric? Report of two cases and review of literature. Cancer. 1969;24(5):923–931. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196911)24:5<923::aid-cncr2820240509>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parham DM, Pratt CB, Parvey LS, Webber BL, Champion J. Childhood multifocal osteosarcoma. Clinicopathologic and radiologic correlates. Cancer. 1985;55(11):2653–2658. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850601)55:11<2653::aid-cncr2820551121>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKenna RJ, Schwinn CP, Soong KY, Higinbotham NL. Sarcomata of the osteogenic series (osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, parosteal osteogenic sarcoma, and sarcomata arising in abnormal bone): an analysis of 552 cases. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 1966;48:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahlin DC, Coventry MB. Osteogenic sarcoma. A study of six hundred cases. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 1967;49(1):101–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones RD, Reid R, Balakrishnan G, Barrett A. Multifocal synchronous osteosarcoma: the Scottish Bone Tumour Registry experience. Medical and Pediatric Oncology. 1993;21(2):111–116. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950210206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzgerald RH, Jr, Dahlin DC, Sim FH. Multiple metachronous osteogenic sarcoma. Report of twelve cases with two long-term survivors. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 1973;55(3):595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Price CHG. Multifocal osteogenic sarcoma. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 1957;39:524–533. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.39B3.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iavarone A, Matthay KK, Steinkirchner TM, Israel MA. Germ-line and somatic p53 gene mutations in multifocal osteogenic sarcoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89(9):4207–4209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.4207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potepan P, Luksch R, Sozzi G, et al. Multifocal osteosarcoma as second tumor after childhood retinoblastoma. Skeletal Radiology. 1999;28(7):415–421. doi: 10.1007/s002560050540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopper KD, Moser RP, Jr, Haseman DB, Sweet DE, Madewell JE, Kransdorf MJ. Osteosarcomatosis. Radiology. 1990;175(1):233–239. doi: 10.1148/radiology.175.1.2315487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enneking WF, Kagan A. “Skip” metastases in osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1975;36(6):2192–2205. doi: 10.1002/cncr.2820360937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batson OV. The vertebral vein system. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1957;78:195–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatori M, Ohtani H, Yamada N, Uzuki M, Kokubun S. Synchronous multifocal osteosarcoma with lymphatic spread in the lung: an autopsy case report. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;31(11):562–566. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hye118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bacci G, Longhi A, Ferrari S, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NC) for synchronous multifocal osteosarcoma (SMO). In: Proceedings of 37th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology; May 2001; San Francisco, Calif. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahoney JP, Spanier SS, Morris JL. Multifocal osteosarcoma. A case report with review of the literature. Cancer. 1979;44(5):1897–1907. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197911)44:5<1897::aid-cncr2820440552>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bacci G, Picci P, Ferrari S, et al. Synchronous multifocal osteosarcoma: results in twelve patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and simultaneous resection of all involved bones. Annals of Oncology. 1996;7(8):864–866. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a010769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]