Abstract

Misfolding and aggregation of protein molecules are major threats to all living organisms. Therefore, cells have evolved quality control systems for proteins consisting of molecular chaperones and proteases, which prevent protein aggregation by either refolding or degrading misfolded proteins. DnaK/DnaJ and GroES/GroEL are the best-characterized molecular chaperone systems in bacteria. In Caulobacter crescentus these chaperone machines are the products of essential genes, which are both induced by heat shock and cell cycle regulated. In this work, we characterized the viabilities of conditional dnaKJ and groESL mutants under different types of environmental stress, as well as under normal physiological conditions. We observed that C. crescentus cells with GroES/EL depleted are quite resistant to heat shock, ethanol, and freezing but are sensitive to oxidative, saline, and osmotic stresses. In contrast, cells with DnaK/J depleted are not affected by the presence of high concentrations of hydrogen peroxide, NaCl, and sucrose but have a lower survival rate after heat shock, exposure to ethanol, and freezing and are unable to acquire thermotolerance. Cells lacking these chaperones also have morphological defects under normal growth conditions. The absence of GroE proteins results in long, pinched filamentous cells with several Z-rings, whereas cells lacking DnaK/J are only somewhat more elongated than normal predivisional cells, and most of them do not have Z-rings. These findings indicate that there is cell division arrest, which occurs at different stages depending on the chaperone machine affected. Thus, the two chaperone systems have distinct roles in stress responses and during cell cycle progression in C. crescentus.

Caulobacter crescentus, an aquatic bacterium and a member of the α subdivision of the Proteobacteria, produces two cell types: motile, DNA replication-quiescent “swarmer cells” and sessile, DNA replication-competent “stalked cells.” The former are important for dispersion, and the latter are important for reproduction (65).

Each motile swarmer cell has a single polar flagellum and several pili at one pole. CtrA, a DNA-binding response regulator that directly controls transcription of at least 95 genes in 55 operons (48), is present in swarmer cells, where it binds to the C. crescentus origin of replication and blocks replication initiation (61). Simultaneously, CtrA directly represses transcription of gcrA (35), ftsZ (44), and podJ (12), blocking the early steps in cell division and polar development. Swarmer cells undergo differentiation to stalked cells, during which the polar pili, flagellum, and chemotaxis apparatus are lost and are replaced by a stalk that grows at the pole previously occupied by the flagellum. Concurrent with the swarmer cell-stalked cell transition, CtrA is degraded (60), while DnaA levels increase (31). The presence of DnaA, not just the absence of CtrA, is required to trigger an increase in GcrA levels and start the next wave of cell cycle transcription, which includes expression of genes encoding nucleotide biosynthesis and DNA replication enzymes. Thus, DnaA not only initiates DNA replication but also promotes the transcription of the components necessary for successful chromosome duplication and the transcription of ftsZ and podJ, starting the cell division and polar organelle development processes that prepare the cell for asymmetric division (35).

More than 19% of the C. crescentus genes have discrete times of transcriptional activation and repression during a normal cell cycle (49). For each cell cycle-regulated event, a set of associated genes is induced immediately before or coincident with the event (49). The DnaK chaperone is synthesized at defined times in the C. crescentus cell cycle (29, 30). The dnaK/J genes are transcribed just before the S phase during the transition from swarmer cells to stalked cells and again in late predivisional cells just before the initiation of DNA replication in the progeny stalked cells (29). Expression of the groESL operon is also under cell cycle control in C. crescentus, and GroEL levels are higher in predivisional cells (4, 30). These observations indicated possible roles of DnaK and GroEL chaperones in specific events of the C. crescentus cell cycle.

In bacteria, the major molecular chaperones include the DnaK machine (67) and the GroE machine (GroES and GroEL). Molecular chaperones protect newly synthesized or stress-denatured polypeptides from misfolding and aggregation in the highly crowded cellular environment, often in an ATP-driven process (24, 33). The C. crescentus dnaKJ (3, 29) and groESL operons (4, 5), in addition to lon (81), hrcA/grpE (63), ftsH (23), and clpB (69), are heat shock inducible and are all positively controlled by the specific heat shock sigma factor σ32. The rpoH gene encoding σ32 is also heat shock inducible, as one of its promoters was shown to be σ32 dependent, indicating that there is autogenous control of rpoH transcription in C. crescentus (62, 82). Similar to its role in Escherichia coli, DnaK is a negative modulator of the heat shock response in C. crescentus, acting by inhibiting σ32 activity and stimulating degradation of this molecule (13). However, despite the strong effect of DnaK levels on the induction phase of the response, the shutoff of heat shock protein (HSP) synthesis is not affected by changes in the amount of this chaperone. Competition between σ32 and σ73, the major sigma factor in C. crescentus, which was shown also to be heat shock inducible, has been proposed as the important factor controlling the downregulation of HSP synthesis during the recovery phase (13). Moreover, the absence of the chaperone ClpB delays the shutoff of HSP synthesis in C. crescentus. Reactivation of heat-inactivated σ73 in this bacterium was shown to be dependent on ClpB chaperone activity, indicating that ClpB levels control downregulation of the heat shock response in C. crescentus (69).

In E. coli, the ribosome-associated trigger factor (TF) cooperates with DnaK and its DnaJ and GrpE cochaperones to assist in the de novo folding of at least 340 cytosolic proteins. The TF/DnaK-dependent proteins have a broad size range, between 16 and 167 kDa, and the number of multidomain proteins is particularly high (15, 73). Neither TF nor DnaK is absolutely essential for E. coli viability, but deletion of both of them results in synthetic lethality at temperatures of >30°C (15, 73). Other chaperones, including GroES/GroEL, can partially compensate for the combined loss of TF and DnaK (25, 74, 76). Indeed, the chaperonin GroEL and its cofactor GroES are the only E. coli chaperones that are essential for viability under all growth conditions tested (21, 36). GroES/EL interact with about 5 to 15% of newly synthesized proteins, and the predominant size range of these proteins is 20 to 60 kDa (8, 19, 38, 39), suggesting that the GroE system plays a role in the de novo folding of these proteins. Some proteins that are too large to be encapsulated can nevertheless utilize GroEL for folding by cycling on and off the GroEL ring in trans to bind GroES (10). Recently, Kerner et al. (45) described characterization of the GroEL substrate proteome by a combination of biochemical analyses and quantitative proteomics. Approximately 250 of the ∼2,400 cytosolic E. coli proteins interact with GroEL in wild-type cells, and the number increases substantially in cells lacking the upstream chaperones TF and DnaK. However, only ∼85 substrates exhibit an obligate dependence on GroEL for folding under normal growth conditions, occupying 75 to 80% of the GroEL capacity (45).

Several reports have shown that GroES/GroEL and DnaK/DnaJ are induced during environmental conditions other than heat shock, such as osmotic and saline stresses, oxidative stress, pH extremes, UV radiation, and the presence of toxic compounds (ethanol, antibiotics, heavy metals, and aromatic compounds) (20, 32, 58, 72). However, the importance of these chaperones for bacterial survival under these harmful conditions has not been comprehensively investigated. In this work, we analyzed C. crescentus groESL and dnaKJ conditional mutant strains SG300 and SG400 to determine their abilities to survive in the presence of various environmental stresses, including heat shock at 42°C and 48°C, oxidative stress (2.5 mM H2O2), a high concentration of ethanol (15%), freezing (−80°C), saline and osmotic stresses (85 mM NaCl and 150 mM sucrose, respectively), and acquisition of thermotolerance. In addition, we also analyzed the aberrant cell division phenotypes related to the lack of GroES/GroEL and DnaK/DnaJ in C. crescentus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

C. crescentus strains were grown at 30°C in PYE complex medium (57) supplemented with either 0.2% glucose (PYEG) or 0.2% xylose (PYEX). The C. crescentus strains used were NA1000, a holdfast mutant derivative of wild-type strain CB15 (18); SG300, containing the groESL operon under control of the PxylX promoter; and SG400, containing the dnaKJ operon under control of the PxylX promoter (13).

Determination of cell viability.

Strains SG300 and SG400 were tested for sensitivity to different stress conditions, and parental strain NA1000 was used as a control in all experiments. Overnight NA1000 cultures were diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 in PYE and incubated in a rotary shaker at 30°C for 6 h. Overnight cultures in PYEX of conditional mutants SG300 and SG400 were washed several times in PYE to remove all the remaining xylose, diluted in PYE, PYEX, or PYEG, and incubated at 30°C for 6 h. In PYE and PYEG, this time was long enough to deplete GroES/GroEL or DnaK/DnaJ from the cells. Aliquots of cells were exposed to heat shock at 42°C, 15% ethanol, or 2.5 mM hydrogen peroxide. For each data point, serial dilutions of the cultures were made and plated on PYEX agar plates. Typically, 10 μl or 100 μl of a 10−4 or 10−6 dilution was plated in order to obtain a convenient number of colonies for counting (30 to 300 colonies). The plates were then incubated for 2 days at 30°C, and colonies were counted to determine the number of CFU/ml for each time. In the freezing experiments, exponentially growing bacterial cultures were frozen and incubated for up to 144 h at −80°C, and the numbers of viable cells were determined as described above. The responses to saline and osmotic stresses were also tested with exponential-phase cultures in PYE by adding 85 mM (final concentration) NaCl and 150 mM (final concentration) sucrose, respectively, and incubating the cells for up to 8 h at 30°C. The numbers of viable cells were determined as described above. To test for the involvement of GroES/GroEL and DnaK/J in induced thermotolerance, mutant strains SG300 and SG400 and parental strain NA1000 were grown in liquid PYE at 30°C for 6 h. Each culture was then divided into two aliquots; one of the aliquots was maintained at 30°C, and the other was incubated at 40°C for 30 min. After this, both aliquots were subjected to heat treatment at 48°C for 60 min. Cultures were then serially diluted in PYE and plated on PYEX agar to determine the numbers of viable cells.

Immunoblot assays.

Samples of C. crescentus cells were taken at regular intervals during heat shock or during growth in the absence of xylose, centrifuged, and resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer, and equal amounts of total protein were separated by denaturing sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (47) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were treated as previously described (4) using anti-DnaK and anti-GroEL antisera of C. crescentus (5). The blots were developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Amersham). Quantification of the immunoblots was carried out by densitometry scanning of the X-ray films using the ImageMaster-VDS software (Pharmacia Biotech).

Preparation of cells for light microscopy.

Overnight cultures of conditional mutants SG300 and SG400 were washed several times to remove the xylose and then diluted to obtain an OD600 of 0.1 in PYEX or PYEG. Samples were collected after 1, 6, 10, and 24 h of growth, and cell morphology was assessed by light microscopy with a Nikon TE300 microscope, using a Planfluor 100× objective lens. Cells grown for 10 h were stained with a LIVE/DEAD Baclight viability kit to determine the in situ viability or with FM1-43 (Molecular Probes) for fluorescent staining of the cytoplasmic membrane. Cells were prepared by diluting cultures 1:1 with PYE and adding 1 μl of mixed LIVE/DEAD stain and then were observed immediately. FM1-43 was added from a 1 mM stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide directly to the cells in growth medium to obtain a final concentration of 1 μM. Samples used for imaging the cells and membranes were mounted on poly-l-lysine-treated slides. SYTO 9 from the LIVE/DEAD kit and FM1-43 were detected using a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) filter (Nikon EF-4 B-2E/C), and propidium iodide was detected with a red band-pass filter (Nikon EF-4 G-1B).

For FtsZ immunolocalization, samples were prepared by methanol fixation as previously described (34) and incubated overnight at room temperature with anti-FtsZ antibody (1:1,000; kind gift from Y. V. Brun). Goat anti-rabbit FITC-conjugated secondary antibody was used at a dilution of 1:50 in phosphate-buffered saline containing 2% bovine serum albumin and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were imaged using an FITC filter, and the images were captured and processed using the Metamorph software, version 4.5 (Universal Imaging, Media, PA).

RESULTS

GroEL and DnaK levels in conditional mutant strains SG300 and SG400.

To analyze the effects of different stresses on the survival of C. crescentus cells lacking the chaperones DnaK/J or GroES/EL, we used conditional mutants SG300 and SG400, which contain single functional chromosomal copies of groESL and dnaKJ, respectively, under control of the xylose-inducible promoter from the xylX gene (13). Since the regulation of these operons in parental strain NA1000 is complex, we initially compared the levels of GroEL and DnaK in SG300 and SG400 cells under both permissive and restrictive conditions with the corresponding wild-type levels.

As shown in Fig. 1, the GroEL levels in SG300 cells grown in the presence of xylose were about 50% lower than the levels in NA1000, whereas the opposite situation was observed for DnaK levels in SG400 cells, which were 80% higher than the levels in the parental strain, under the same growth conditions (Fig. 1). This probably reflected the strength of the wild-type promoters of each operon compared with the strength of the PxylX promoter. In addition, whereas the GroEL levels were similar in NA1000 and SG400 cells growing in the presence of xylose (Fig. 1), the amount of DnaK was 50% larger in SG300 cells grown under the same conditions than the amount in the parental strain (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

GroEL and DnaK levels in groESL and dnaKJ conditional mutants. Cells from parental strain NA1000 and from conditional mutants SG300 and SG400, in which the groESL and dnaKJ operons, respectively, are under control of promoter PxylX, were grown at 30°C in the presence or absence of xylose for 6 h. At different times, samples were collected and proteins were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by immunoblotting using antisera against C. crescentus GroEL and DnaK, as described in Material and Methods. Equal amounts of protein were applied to all lanes.

As previously shown (13), when xylose was removed from the culture media, there was a marked reduction in the amount of GroEL in SG300, and this protein was undetectable after 6 h of incubation in the absence of the inducer (Fig. 1). Concomitantly, there was an increase in the DnaK level (Fig. 1), which was 50% higher than the wild-type level under permissive conditions and was threefold higher than the wild-type level in SG300 cells grown without xylose (Fig. 1). A similar behavior was seen when SG400 cultures were grown in the absence of xylose, and the level of GroEL increased significantly (1.8-fold) as DnaK in the cells was depleted (Fig. 1). The increase in the level of DnaK when GroEL in the cells was depleted and vice versa indicated that the absence of each of the chaperones led to accumulation of partially denatured proteins, which caused an increase in the amount of σ32 in both cases, as previously described (13). The increase in σ32 levels was shown to be quite large in SG400 cells after the removal of xylose (the levels were about 20-fold higher than wild-type levels); the maximum was reached by 5 h under nonpermissive conditions, and the level remained high even 24 h later. In SG300 cells, the increase in the level of σ32 was smaller (2.5-fold lower), with a peak after 5 h of growth without xylose, and the level decreased slowly after this peak (13). The larger amount of σ32 in each depleted mutant strain in turn induced the transcription of heat shock genes, resulting in an increased rate of synthesis of the other chaperone, whose gene was still under control of a σ32-dependent promoter.

DnaK/DnaJ and GroES/EL are necessary during cell growth at different temperatures.

Previous work in our laboratory showed that both the DnaK and GroEL proteins are essential for C. crescentus viability, since mutants with deletions in the corresponding genes could be obtained only when a wild-type copy of each gene was provided in trans or when conditional mutants were constructed (13). As these experiments were carried out with cultures growing at 30°C, we examined whether this was also the case at other temperatures. In fact, in the absence of xylose, mutant strains SG300 and SG400 were not able to form colonies at 16°C, 30°C, or 37°C (not shown). Moreover, SG300 did not form colonies at the highest temperature tested (37°C) even in the presence of xylose (not shown). These results showed that both GroES/EL and DnaK/J were essential at all temperatures tested and that the levels of GroES/EL obtained in the presence of xylose were not sufficient for growth at 37°C.

DnaK/DnaJ are important during heat shock.

SG300 and SG400 cells growing in the presence of xylose were just as viable as cells of parental strain NA1000 during exposure to 42°C for 2 h (Fig. 2). However, when C. crescentus SG300 and SG400 cells grown in the presence of glucose were subjected to the same stress conditions, depletion of DnaK/J led to a marked decrease in viability (the viability was 2,600-fold lower than the NA1000 viability), whereas the viability of cells lacking the GroE proteins was not affected (Fig. 2). Similar results were obtained when C. crescentus cells were exposed to extreme heat treatment at 48°C for 60 min, and cells with DnaK/J depleted exhibited much greater sensitivity than cells with GroES/EL depleted (Fig. 3). Interestingly, SG300 cells with the GroE proteins depleted survived in the presence of this extreme temperature better than parental strain NA1000 cells survived (Fig. 3). The DnaJ/DnaK chaperone machine was also shown to be necessary for C. crescentus cells to acquire thermotolerance to extreme temperatures. Cultures of SG400 preincubated at 40°C for 30 min survived exposure to 48°C as well as the wild-type cells only when xylose was present in the growth medium (Fig. 3). In contrast, there was a significant increase in the ability SG300 cells growing under restrictive conditions to survive exposure to 48°C when cells were pretreated at 40°C (Fig. 3). This was probably due to the higher levels of DnaK/DnaJ present in SG300 cells in all conditions tested (Fig. 1). Thus, these results indicated that the presence of DnaK/DnaJ is very important for the survival of cells exposed to heat stress, whereas GroES and GroEL are not necessary.

FIG. 2.

Induction of DnaK/J synthesis but not induction of GroES/EL synthesis is important for survival after heat shock. Overnight SG300 and SG400 cultures growing in PYEX at 30°C were washed, diluted in PYEX or PYEG, and incubated for 6 h at 30°C. Cells were then transferred to a 42°C water bath with agitation, and samples were taken at different times and plated on PYEX. The survival values are the averages of three independent experiments, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations. Light gray bars, SG400 diluted in PYEX; open bars, SG400 diluted in PYEG; black bars, SG300 diluted in PYEX; dark gray bars, SG300 diluted in PYEG.

FIG. 3.

Absence of DnaK/J makes SG400 cells incapable of acquiring thermotolerance. Cultures of strains SG300 and SG400 were incubated at 30°C for 12 h in PYEX, and cells were subsequently washed, diluted in PYEX or PYEG, and incubated for 6 h at 30°C. A similar procedure was used for parental strain NA1000, except that only PYE was used. One half of the cultures were preconditioned for 30 min at the nonlethal temperature (40°C) (gray bars), while the other half of the cultures were preincubated at 30°C (open bars). The cultures were then exposed to 48°C for 30 min, and cell survival was evaluated after dilution and plating on PYEX agar. The values are the levels of cell survival (averages of three independent experiments) compared with the survival of control cultures grown in the absence of stress. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

DnaK/DnaJ are involved in the survival of cells exposed to ethanol and freezing.

Several other stresses were tested in cells with DnaK/DnaJ or GroES/GroEL depleted in order to assess the roles of these chaperones in cell survival after exposure to different environmental conditions. Strain SG400 grown in the absence of xylose was about six times more sensitive to 15% ethanol than wild-type or SG300 cells were under the same conditions (Fig. 4A), indicating that DnaK/J but not GroES/EL is important for protecting C. crescentus cells against the deleterious effects of ethanol, such as dehydration, membrane disturbance, and the resulting protein denaturation.

FIG. 4.

Depletion of DnaK/J makes cells more sensitive to ethanol and freezing. (A) Overnight cultures of SG400 or SG300 in PYEX were washed, diluted in PYEX or PYEG, and incubated for 6 h at 30°C for depletion of DnaK/J or GroES/EL. The cultures were then exposed to 15% (vol/vol) ethanol, and samples were collected at different times and plated on PYEX. (B) Samples of the 6-h cultures were frozen at −80°C without any supplement. At different times, aliquots were transferred to room temperature, allowed to defrost, diluted, and plated on PYEX. The bars indicate the averages of three independent experiments, and the error bars indicate standard deviations. Light gray bars, SG400 diluted in PYEX; open bars, SG400 diluted in PYEG; black bars, SG300 diluted in PYEX; dark gray bars, SG300 diluted in PYEG.

It was recently shown that C. crescentus cells are quite resistant to freezing (E. Lang and M. V. Marques, personal communication). We observed that NA1000 cultures kept frozen at −80°C for several days in the absence of any antifreezing agent were 100% viable when they were plated on nutrient medium at 30°C. The same behavior was observed with SG300 cells in which GroES/EL were depleted or not depleted. However, SG400 cells lacking DnaK/J were more sensitive to freezing, exhibiting decreased viability (80%) after incubation for 1 h at −80°C; only 30% of the cells were still viable after incubation for 18 h or more (Fig. 4B).

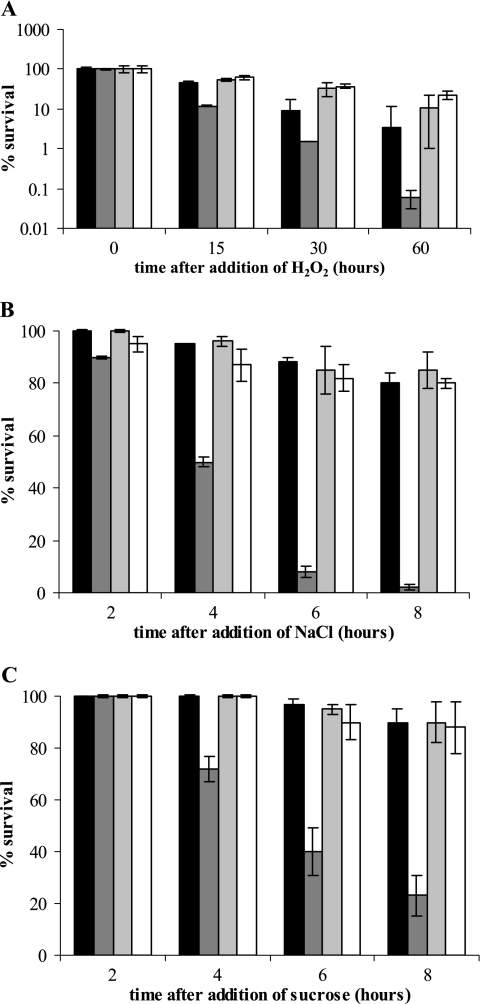

GroES/GroEL are important during oxidative, osmotic, and saline stresses.

Even though GroES/EL were shown to be dispensable for survival of C. crescentus cells exposed to heat shock, ethanol, and freezing, their presence during oxidative, saline, and osmotic stresses was found to be very important. As shown in Fig. 5A, SG300 cells lacking GroES/EL were 10-fold more sensitive to incubation with 2.5 mM H2O2 for 60 min than wild-type cells or SG400 cells with DnaK/J depleted. In addition, the presence of 150 mM sucrose in the growth medium resulted in a fivefold decrease in the viability of SG300 cells with GroES/EL depleted compared with the viability of the wild-type cells after 8 h of incubation under osmotic stress conditions. Exposure to 85 mM NaCl had an even more pronounced effect, as only 2% of SG300 cells growing in the absence of xylose were viable after 8 h of saline stress (Fig. 5B). Under the same conditions, SG400 cells with DnaK/J depleted or not depleted (Fig. 5B and C) and NA1000 cells (not shown) showed no loss of viability.

FIG. 5.

Depletion of GroES/EL results in increased sensitivity to oxidative, osmotic, and saline stresses. Overnight cultures of SG400 or SG300 in PYEX were washed, diluted in PYEX or PYEG, and incubated for 6 h at 30°C. The cultures were divided and exposed to 2.5 mM H2O2 (A), 85 mM NaCl (B), or 150 mM sucrose (C), and samples were collected at different times and plated on PYEX. The values are the levels of cell survival (averages of three independent experiments) compared with the survival of control cultures grown in the absence of stress. The error bars indicate standard deviations. Light gray bars, SG400 diluted in PYEX; open bars, SG400 diluted in PYEG; black bars, SG300 diluted in PYEX; dark gray bars, SG300 diluted in PYEG.

Viability and morphology of cells with DnaK/J or GroES/EL depleted.

Viability studies of SG300 and SG400 cells growing under permissive or restrictive conditions were also carried out using the LIVE/DEAD BacLight staining mixture (Molecular Probes), which distinguishes viable bacterial cells from dead cells on the basis of membrane integrity and has been used to monitor damage to bacterial populations (75). Our studies with LIVE/DEAD staining showed that SG300 cultures contained 48% viable cells after 10 h of growth at 30°C in the absence of xylose, whereas in the presence of xylose 95% of the cells were still viable (not shown). In contrast, depletion of DnaK/DnaJ did not seem to significantly affect the viability of SG400 cells during growth for up to 10 h under restrictive conditions, since 93% of the cells were found to be viable under these conditions (not shown).

Determination of the number of CFU by plating SG300 cells growing at 30°C in the absence of xylose revealed a steady decrease in viability starting after 6 h of incubation in the absence of xylose, and the level of viability was very low after 24 h (Fig. 6A). In agreement with LIVE/DEAD staining results, there was a much smaller decrease in the viability of SG400 cells even after 24 h of incubation in absence of xylose (Fig. 6B). The increase in cell mass, as determined by measuring the OD600 of the cultures, also agreed with the LIVE/DEAD data; i.e., SG400 cultures growing in the absence of xylose produced a growth curve similar to that of the parental cell culture up to 12 h, whereas the SG300 growth curve deviated significantly from the growth curve for the parental strain after 8 h of incubation without xylose (not shown).

FIG. 6.

Survival of mutant strains SG300 and SG400 under restrictive or permissive growth conditions. Cultures of strains NA1000 (A and B), SG300 (A), and SG400 (B) were grown in PYEX or PYEG liquid medium at 30°C and monitored through the logarithmic and stationary growth phases. The numbers of CFU were determined at different times by plating cell samples on solid medium (PYEX). The values are the averages of three independent experiments. •, SG300 grown in PYEX; ○, SG300 grown in PYEG; ▴, SG400 grown in PYEX; ▵, SG400 grown in PYEG; ▪, NA1000.

Morphologically, cells with either GroES/EL or DnaK/J depleted were elongated, suggesting that there was a defect in cell division in both cases, although large differences between the two strains were observed. Cells with GroES/EL depleted formed very long filaments (Fig. 7B), whereas cells with DnaK/J depleted were only somewhat more elongated than wild-type predivisional cells (Fig. 7D). In addition, in the absence of DnaK/J some cells seemed to lose the vibrioid shape, especially 24 h after xylose was removed (Fig. 7F).

FIG. 7.

Altered morphology of SG300 and SG400 cells lacking GroES/L or DnaK/J. Strains SG300 (A and B) and SG400 (C to F) were grown in PYEX (A, C, and E) or PYEG (B, D, and F). Cells were visualized by light microscopy using a 100× objective and differential interference contrast optics after 10 h (A to D) and 24 h (E and F) of incubation at 30°C.

Most SG300 cells grown for 10 h in the absence of xylose were found to be 8 to 13 μm long, while the cells grown with xylose were 2 to 3.4 μm long, in agreement with the size distribution pattern for wild-type cells (not shown). Therefore, depletion of GroES/EL led to fourfold-longer cells. In contrast, SG400 cells with low levels of DnaK/J were only 1.4-fold longer than the cells grown in the presence of xylose or than wild-type cells (not shown).

DnaK/J and GroES/EL are required for C. crescentus cell division.

To better characterize the effect of DnaK/J or GroES/EL depletion on C. crescentus cell division, a membrane dye (FM1-43 from Molecular Probes) was used to assess whether septa were formed in SG300 and SG400 elongated cells.

Most SG300 cells with GroES/EL depleted had deep, irregular constrictions along the filaments, and only a few cells (∼4%) lacked such constrictions (Fig. 8B). The position of the division sites was quite variable in these cells, and some filaments consisted of long unpinched segments adjacent to minicells or cells that were the regular size. In contrast, only 11% of the SG400 cells with DnaK/DnaJ depleted had a septum or shallow constriction in the middle of the cell (Fig. 8D). The same strains grown under permissive conditions (Fig. 8A and C), as well as wild-type strain NA1000 (not shown), had one septum per cell in about 35 to 41% of the population, corresponding to the percentage of predivisional cells in a normal mixed-cell population.

FIG. 8.

Septum formation in SG300 and SG400 cells grown under restrictive conditions. After incubation for 10 h in PYEX (A and C) or PYEG (B and D), SG300 (A and B) and SG400 (C and D) cells were stained with the membrane dye FM1-43, and images were captured using a 100× objective and an FITC filter. Arrowheads indicate invagination of the cytoplasmic membrane.

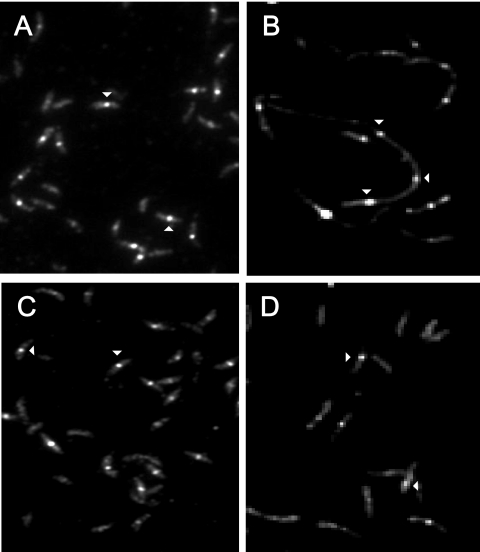

Since an important step in septum formation is the appearance of a Z-ring in the equatorial region of the cell, an anti-FtsZ antibody was used to visualize this structure by immunofluorescence microscopy. Again, the results obtained for SG300 and SG400 cells grown in the presence of xylose were similar to the results obtained for NA1000 cells: a Z-ring was present in 70% of the cells, corresponding to the percentage for predivisional cells and for stalked cells in transition to predivisional cells (Fig. 9A and C). Cells that lacked a Z-ring were swarmer or stalked cells in the first stages of chromosome replication. Under restrictive conditions, however, 92% of the SG300 cells had Z-rings (Fig. 9B), in contrast to only 8% of the SG400 cells (Fig. 9D). These results indicated that depletion of DnaK/DnaJ and depletion of GroES/GroEL affect different stages of the cell division process.

FIG. 9.

Immunolocalization of FtsZ in SG300 and SG400 cells. After 10 h of incubation in PYEX (A and C) or PYEG (B and D), SG300 (A and B) and SG400 (C and D) cells were collected and prepared for immunofluorescence microscopy using the anti-FtsZ antibody and an FITC-labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Images were captured with a Roper CoolSnap HQ cooled charge-coupled device camera using a 100× objective and an FITC filter. Arrowheads indicate the Z ring.

DISCUSSION

Several lines of experimental evidence demonstrated that heat shock proteins not only have essential functions at high temperatures or under harsh environmental conditions but also have important roles under physiological growth conditions. In agreement with this, we report here that both GroES/GroEL and DnaK/DnaJ are essential for C. crescentus growth at all temperatures tested (37°C, 30°C, and 16°C). A similar observation was made for E. coli GroES/GroEL (21), whereas DnaK was found to be essential only at high temperatures (9). Furthermore, DnaK is not required for growth of Bacillus subtilis at temperatures ranging from 16 to 52°C (67), whereas GroES/EL are essential both at normal temperatures and during heat stress (51).

Our results indicate that during heat shock there is major involvement of DnaK/J compared to the involvement of GroES/EL, since a lack of DnaK/J had a great impact on cell survival at high temperatures (both 42°C and 48°C), whereas the percentage of cells that survived in the absence of GroE proteins was similar to or even higher than the percentage of parental cells that survived after exposure to 42°C or 48°C. The importance of the role of DnaK/J at high temperatures is further supported by our observation that only these chaperones were essential for acquisition of thermotolerance. These results are consistent with the suggestion that DnaK/J have a greater role as molecular chaperones than GroES/EL (11, 16).

The observation that the absence of GroES/EL did not make SG300 cells more sensitive to heat shock could be explained by the presence of higher levels of DnaK at 30°C in these cells both in the presence and in the absence of xylose compared to the levels in parental cells (1.5- and 3-fold-higher levels, respectively).

Similarly, DnaK/J seemed to play a more important role than GroES/EL played when C. crescentus cells were exposed to high ethanol concentrations. This was probably due to the fact that ethanol mimics the effects of high-temperature stress and induces a response similar to the heat shock response (2, 55, 56, 68). As expected, ethanol stress caused a transient increase in σ32 levels and a gradual increase in DnaK and GroEL levels in C. crescentus (data not shown).

Recently, our laboratory reported that the absence of ClpB makes C. crescentus cells more sensitive to heat shock and ethanol and that this chaperone is needed for acquisition of thermotolerance (69). Based on the similar phenotypes of the clpB null mutant and the dnaK mutant under restrictive conditions, we believe that DnaK and ClpB may act synergistically, preventing and solubilizing protein aggregates during heat shock and ethanol stress in C. crescentus, as previously proposed (28).

During oxidative stress, enzymes and cell structures are damaged, leading to a loss of viability in bacterial populations (20, 42, 71). In several bacteria, it has been shown that the oxidative stress response overlaps other stress responses, such as the heat shock, starvation, and SOS responses (71). Expression of GroEL and DnaK is induced during treatment with H2O2 in several bacteria (17, 20, 32), as well as in C. crescentus (data not shown). In addition, it has been reported that Haemophilus ducreyi cells with lower GroEL levels have a diminished ability to survive when they are challenged by oxidative stress (56) and that E. coli dnaK mutants are able to develop an adaptive H2O2 resistance (64).

The present work showed that C. crescentus cells with low levels of GroES/EL are more sensitive to oxidative stress induced by H2O2 than the parental strain is, while cells with DnaK/J depleted have the parental phenotype. This result may be explained by the reported ability of GroEL to function under oxidative stress conditions and to be highly resistant to oxidative damage compared to other proteins (53, 54).

Our data also showed that GroES/GroEL are essential for C. crescentus during salt and osmotic stresses. When exposed to osmotic upshifts, bacteria respond in three overlapping phases: dehydration, adjustment of cytoplasmic solvent composition, and rehydration and cellular remodeling (80). Similar effects occur when cells are subjected to high concentrations of salt (43). The reason why GroES/GroEL are needed for C. crescentus survival in high-osmolarity conditions could be the chaperoning of newly synthesized proteins that are rapidly upregulated upon osmotic shock (e.g., the proteins of the K+ transporter, KdpACDF) and/or the refolding of polypeptides damaged as a result of water efflux (6, 43). It has been shown that many outer membrane proteins, such as OmpA, OmpC, OmpF, and murein lipoprotein, have a partial GroES/EL requirement in E. coli (45). GroES/EL may also participate in the translocation and insertion into the membrane of transporters involved in the osmotic response. In fact, several reports have shown that GroEL can form complexes with native membrane proteins in vitro (7, 14, 70). Lecker et al. (50) showed that there is a stable interaction between GroEL and a presecretory protein (proOmpA), maintaining an open conformation, which is essential for translocation.

The importance of GroES/EL for survival during osmotic and salt stresses is reflected by the higher groESL promoter activity in C. crescentus under these conditions (not shown). In agreement with a less important role for DnaK/J in cell survival, dnaKJ promoter activity increases less under these stress conditions (not shown).

For cold shock and freezing, the absence of DnaK/J resulted in a decrease in the ability of C. crescentus cells to survive in freezing temperatures, whereas the absence of GroES/EL had no effect. Protein renaturation after cold shock and freezing seems to be more crucial to bacteria than during these stresses; therefore, the chaperones are more important in the recovery phase. In E. coli, it was also shown that it is mainly DnaK that allows cells to survive after freezing, as a dnaK mutant performed worse than a groEL mutant during recovery from this stress (11).

The fact that groESL and dnaKJ expression is regulated during the C. crescentus cell cycle indicates that these chaperones have important roles in events related to chromosome replication and partition and/or cell division. Bacterial cell division involves several genes, and their products might require chaperones to function properly. One of the major cell division determinants, the tubulin homologue FtsZ, is present in almost all eubacteria and archaea, as well as in some intracellular organelles of eukaryotic cells. FtsZ localizes specifically to the midcell division site, where it forms the cytokinetic Z-ring, which constricts the cell membrane during septation. In both E. coli and C. crescentus, ftsZ mutant strains form unpinched elongated cells due to their inability to initiate cell division (1, 78). FtsA, an actin homologue, is required for cell division progression in C. crescentus, since cells lacking FtsA form filaments that have several constrictions, indicating that cell division has initiated but stalled at a later point than it stalls in ftsZ mutants (52). This phenotype was also observed in Caulobacter cells lacking GroES/EL, where several Z-rings were detected in the filaments. This observation indicated that cell division was inhibited at a stage consistent with the time when the level of expression of the groESL operon was maximum, which was the predivisional cell stage (4).

In E. coli, FtsE, ParC, and MreB, which are required in later stages of cell division, were found to be obligatory substrates for the GroE machine (45). Whereas FtsE participates directly in cell division and is important for assembly or stability of the septal ring in E. coli (66), DNA topoisomerase IV, which is the product of the parC and parE genes, is required for polar localization of the origin of replication and for chromosome segregation in C. crescentus (77, 79). Incubation of parC and parE temperature-sensitive mutants at the restrictive temperature results in the formation of filamentous chains of cells pinched at multiples sites (79), similar to the phenotype of cells with GroE proteins depleted. Inactivation of the actin homologue MreB is lethal and pleiotropic in C. crescentus (22, 26) and disrupts multiple cellular processes, including chromosome dynamics, determination of the cell shape, polar protein localization, and cell division (27). The possibility that many proteins related to various stages of the cell cycle and cell morphogenesis could be partially or completely inactive due to a lack of GroES/EL could explain the heterogeneity of SG300 phenotypes under restrictive conditions.

After 10 h under restrictive conditions, cells lacking DnaK/J are only slightly more elongated than wild-type predivisional cells, indicating that there is a putative arrest of the cell cycle. Cells with DnaK/J depleted also show inhibition of septum formation, since only 8% of the cells have a septum or are constricted in the midcell region. The absence of Z-rings from most cells indicates that blockage of septum formation may occur at the initial stage of cell division. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that cells with DnaK/J depleted are arrested at an early stage of the cell cycle, probably at the initial steps of chromosome replication or segregation.

It is well known that initiation of replication and chromosome segregation in C. crescentus is coupled with cell division and differentiation (59). This occurs because inhibition of replication by CtrA blocks the complete formation of a septum, since cell division progression requires expression of ftsA and ftsQ, which is dependent on DNA replication. Without FtsA and FtsQ, the Z-ring is dismantled (52) and the division process cannot proceed. During the transition from swarmer cells to stalked cells, CtrA is degraded (60), while the DnaA levels increase (31). The presence of DnaA, and not just the absence of CtrA, is required to trigger an increase in GcrA levels and to start the next wave of cell cycle transcription, which includes the expression of genes encoding nucleotide biosynthesis and DNA replication enzymes. Thus, DnaA not only initiates DNA replication but also promotes expression of the components necessary for successful chromosome duplication. DnaA also activates transcription of ftsZ and podJ, starting the cell division and polar organelle biogenesis processes that, in addition to DNA replication, prepare the cell for asymmetric division (37).

Interestingly, the morphology of C. crescentus cells with DnaA depleted (37) is similar to that of cells with DnaK/J depleted. Thus, it is possible that the arrest in the SG400 cell cycle is a consequence of DnaA inactivation in the absence of DnaK. In agreement with this hypothesis, dnaK transcription in C. crescentus precedes the S phase, right at the transition between swarmer cells and stalked cells, when DNA replication initiates (29). This is also consistent with previous genetic and biochemical evidence suggesting that DnaK/J chaperones could be involved in DNA replication in E. coli. It has been demonstrated that these chaperones could protect DnaA from aggregation and could dissociate DnaA aggregates in vitro, thus allowing the initiation of oriC DNA replication (40, 41, 46).

Besides the putative cell cycle arrest observed in the absence of DnaK, we also noted that after 24 h in the absence of xylose, SG400 cells became more elongated and lost the vibrioid shape characteristic of C. crescentus. This might indicate that DnaK/DnaJ also have a chaperone role in cell shape maintenance, perhaps by interacting with the intermediate filament-like protein crescentin (G. Charbon and C. Jacobs-Wagner, personal communication).

It is important to note, however, that the effects on cell division observed here could have been the result of multiple factors, many of which are not directly related to septum formation. Since GroES/EL and DnaK/J can act on many different substrates, their absence could result in pleiotropic alterations in bacterial physiology.

In conclusion, we showed that DnaK/DnaJ and GroES/GroEL have important but distinct roles in C. crescentus both under normal physiological growth conditions and under different environmental stress conditions. Characterization of the specific substrates of these chaperones is now fundamentally important for unraveling their actual roles in the various biological processes analyzed here.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yves V. Brun for generously supplying anti-FtsZ antiserum. We also thank Marilis V. Marques and Christine Jacobs-Wagner for sharing unpublished results.

This work was supported by a grant from Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP). M.F.S is a fellow of FAPESP, and S.L.G. was partially supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 September 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Addinall, S. G., E. Bi, and J. Lutkenhaus. 1996. FtsZ ring formation in fts mutants. J. Bacteriol. 178:3877-3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnosti, D. N., V. L. Singer, and M. J. Chamberlin. 1986. Characterization of heat shock in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 168:1243-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avedissian, M., D. Lessing, J. W. Gober, L. Shapiro, and S. L. Gomes. 1995. Regulation of the Caulobacter crescentus dnaKJ operon. J. Bacteriol. 177:3479-3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avedissian, M., and S. L. Gomes. 1996. Expression of the groESL operon is cell-cycle controlled in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 19:79-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldini, R. L., M. Avedissian, and S. L. Gomes. 1998. The CIRCE element and its putative repressor control cell cycle expression of the Caulobacter crescentus groESL operon. J. Bacteriol. 180:1632-1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bianchi, A. A., and F. Baneyx. 1999. Hyperosmotic shock induces the σ32 and σE stress regulons of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 34:1029-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bochkareva, E., A. Seluanov, E. Bibi, and A. Girshovich. 1996. Chaperonin-promoted post-translational membrane insertion of a multispanning membrane protein lactose permease. J. Biol. Chem. 271:22256-22261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brinker, A., G. Pfeifer, M. J. Kerner, D. J. Naylor, F. U. Hartl, and M. Hayer-Hartl. 2001. Dual function of protein confinement in chaperonin-assisted protein folding. Cell 107:223-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bukau, B., and G. C. Walker. 1989. Delta dnaK52 mutants of Escherichia coli have defects in chromosome segregation and plasmid maintenance at normal growth temperatures. J. Bacteriol. 171:6030-6038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaudhuri, T. K., G. W. Farr, W. A. Fenton, S. Rospert, and A. L. Horwich. 2001. GroEL/GroES-mediated folding of a protein too large to be encapsulated. Cell 107:235-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chow, K. C., and W. L. Tung. 1998. Overexpression of dnaK/dnaJ and groEL confers freeze tolerance to Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 253:502-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crymes, W. B., Jr., D. Zhang, and B. Ely. 1999. Regulation of podJ expression during the Caulobacter crescentus cell cycle. J. Bacteriol. 181:3967-3973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.da Silva, A. C., R. C. Simão, M. F. Susin, R. L. Baldini, M. Avedissian, and S. L. Gomes. 2003. Downregulation of the heat shock response is independent of DnaK and sigma32 levels in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 49:541-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deaton, J., J. Sun, A. Holzenburg, D. K. Struck, J. Berry, and R. Young. 2004. Functional bacteriorhodopsin is efficiently solubilized and delivered to membranes by the chaperonin GroEL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:2281-2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deuerling, E., A. Schulze-Specking, T. Tomoyasu, A. Mogk, and B. Bukau. 1999. Trigger factor and DnaK cooperate in folding of newly synthesized proteins. Nature 400:693-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellis, R. J., and F. U. Hartl. 1996. Protein folding in the cell: competing models of chaperonin function. FASEB J. 10:20-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ericsson, M., A. Tarnvik, K. Kuoppa, G. Sandstrom, and A. Sjostedt. 1994. Increased synthesis of DnaK, GroEL, and GroES homologs by Francisella tularensis LVS in response to heat and hydrogen peroxide. Infect. Immun. 62:178-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evinger, M., and N. Agabian. 1977. Envelope-associated nucleoid from Caulobacter crescentus stalked and swarmer cells. J. Bacteriol. 132:294-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ewalt, K. L., J. P. Hendrick, W. A. Houry, and F. U. Hartl. 1997. In vivo observation of polypeptide flux through the bacterial chaperonin system. Cell 90:491-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farr, S. B., and T. Kogoma. 1991. Oxidative stress responses in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiol. Rev. 55:561-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fayet, O., T. Ziegelhoffer, and C. Georgopoulos. 1989. The groES and groEL heat shock gene products of Escherichia coli are essential for bacterial growth at all temperatures. J. Bacteriol. 171:1379-1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Figge, R. M., A. V. Divakaruni, and J. W. Gober. 2004. MreB, the cell shape-determining bacterial actin homologue, co-ordinates cell wall morphogenesis in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 51:1321-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer, B., G. Rummel, P. Aldridge, and U. Jenal. 2002. The FtsH protease is involved in development, stress response and heat shock control in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 44:461-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frydman, J. 2001. Folding of newly translated proteins in vivo: the role of molecular chaperones. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:603-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genevaux, P., F. Keppel, F. Schwager, P. S. Langendijk-Genevaux, F. U. Hartl, and C. Georgopoulos. 2004. In vivo analysis of the overlapping functions of DnaK and trigger factor. EMBO Rep. 5:195-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gitai, Z., N. Dye, and L. Shapiro. 2004. An actin-like gene can determine cell polarity in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:8643-8648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gitai, Z., N. A. Dye, A. Reisenauer, M. Wachi, and L. Shapiro. 2005. MreB actin-mediated segregation of a specific region of a bacterial chromosome. Cell 120:329-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goloubinoff, P., A. Mogk, A. P. Zvi, T. Tomoyasu, and B. Bukau. 1999. Sequential mechanism of solubilization and refolding of stable protein aggregates by a bichaperone network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:13732-13737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomes, S. L., J. W. Gober, and L. Shapiro. 1990. Expression of the Caulobacter heat shock gene dnaK is developmentally controlled during growth at normal temperatures. J. Bacteriol. 172:3051-3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gomes, S. L., M. H. Juliani, J. C. Maia, and A. M. Silva. 1986. Heat shock protein synthesis during development in Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 168:923-930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gorbatyuk, B., and G. T. Marczynski. 2005. Regulated degradation of chromosome replication proteins DnaA and CtrA in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 55:1233-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanawa, T., T. Yamamoto, and S. Kamiya. 1995. Listeria monocytogenes can grow in macrophages without the aid of proteins induced by environmental stresses. Infect. Immun. 63:4595-4599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartl, F. U., and M. Hayer-Hartl. 2002. Molecular chaperones in the cytosol: from nascent chain to folded protein. Science 295:1852-1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hiraga, S., C. Ichinose, H. Niki, and M. Yamazoe. 1998. Cell cycle-dependent duplication and bidirectional migration of SeqA-associated DNA-protein complexes in E. coli. Mol. Cell 1:381-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holtzendorff, J., D. Hung, P. Brende, A. Reisenauer, P. H. Viollier, H. H. McAdams, and L. Shapiro. 2004. Oscillating global regulators control the genetic circuit driving a bacterial cell cycle. Science 304:983-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horwich, A. L., and K. R. Willison. 1993. Protein folding in the cell: functions of two families of molecular chaperone, hsp 60 and TF55-TCP1. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 339:313-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hottes, A. K., L. Shapiro, and H. H. McAdams. 2005. DnaA coordinates replication initiation and cell cycle transcription in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 58:1340-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Houry, W. A. 2001. Mechanism of substrate recognition by the chaperonin GroEL. Biochem. Cell Biol. 79:569-577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Houry, W. A., D. Frishman, C. Eckerskorn, F. Lottspeich, and F. U. Hartl. 1999. Identification of in vivo substrates of the chaperonin GroEL. Nature 402:147-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hupp, T. R., and J. M. Kaguni. 1993. DnaA5 protein is thermolabile in initiation of replication from the chromosomal origin of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 268:13128-13136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hwang, D. S., E. Crooke, and A. Kornberg. 1990. Aggregated DnaA protein is dissociated and activated for DNA replication by phospholipase or DnaK protein. J. Biol. Chem. 265:19244-19248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Imlay, J. A. 2003. Pathways of oxidative damage. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:395-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kanesaki, Y., I. Suzuki, S. I. Allakhverdiev, K. Mikami, and N. Murata. 2002. Salt stress and hyperosmotic stress regulate the expression of different sets of genes in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290:339-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelly, A. J., M. J. Sackett, N. Din, E. Quardokus, and Y. V. Brun. 1998. Cell cycle-dependent transcriptional and proteolytic regulation of FtsZ in Caulobacter. Genes Dev. 12:880-893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kerner, M. J., D. J. Naylor, Y. Ishihama, T. Maier, H. C. Chang, A. P. Stines, C. Georgopoulos, D. Frishman, M. Hayer-Hartl, M. Mann, and F. U. Hartl. 2005. Proteome-wide analysis of chaperonin-dependent protein folding in Escherichia coli. Cell 122:209-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Konieczny, I., and K. Liberek. 2002. Cooperative action of Escherichia coli ClpB protein and DnaK chaperone in the activation of a replication initiation protein. J. Biol. Chem. 277:18483-18488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laub, M. T., S. L. Chen, L. Shapiro, and H. H. McAdams. 2002. Genes directly controlled by CtrA, a master regulator of the Caulobacter cell cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:4632-4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laub, M. T., H. H. McAdams, T. Feldblyum, C. M. Fraser, and L. Shapiro. 2000. Global analysis of the genetic network controlling a bacterial cell cycle. Science 290:2144-2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lecker, S., R. Lill, T. Ziegelhoffer, C. Georgopoulos, P. J. Bassford, Jr., C. A. Kumamoto, and W. Wickner. 1989. Three pure chaperone proteins of Escherichia coli—SecB, trigger factor and GroEL—form soluble complexes with precursor proteins in vitro. EMBO J. 8:2703-2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li, M., and S. L. Wong. 1992. Cloning and characterization of the groESL operon from Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 174:3981-3992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martin, M. E., M. J. Trimble, and Y. V. Brun. 2004. Cell cycle-dependent abundance, stability and localization of FtsA and FtsQ in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 54:60-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Melkani, G. C., C. McNamara, G. Zardeneta, and J. A. Mendoza. 2004. Hydrogen peroxide induces the dissociation of GroEL into monomers that can facilitate the reactivation of oxidatively inactivated rhodanese. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 36:505-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Melkani, G. C., G. Zardeneta, and J. A. Mendoza. 2004. Oxidized GroEL can function as a chaperonin. Front. Biosci. 9:724-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park, S. H., K. H. Oh, and C. K. Kim. 2001. Adaptive and cross-protective responses of Pseudomonas sp. DJ-12 to several aromatics and other stress shocks. Curr. Microbiol. 43:176-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Periago, P. M., W. van Schaik, T. Abee, and J. A. Wouters. 2002. Identification of proteins involved in the heat stress response of Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3486-3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Poindexter, J. S. 1964. Biological properties and classification of the Caulobacter group. Bacteriol. Rev. 28:231-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prasad, J., P. McJarrow, and P. Gopal. 2003. Heat and osmotic stress responses of probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 (DR20) in relation to viability after drying. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:917-925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Quardokus, E. M., and Y. V. Brun. 2003. Cell cycle timing and developmental checkpoints in Caulobacter crescentus. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:541-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Quon, K. C., G. T. Marczynski, and L. Shapiro. 1996. Cell cycle control by an essential bacterial two-component signal transduction protein. Cell 84:83-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Quon, K. C., B. Yang, I. J. Domian, L. Shapiro, and G. T. Marczynski. 1998. Negative control of bacterial DNA replication by a cell cycle regulatory protein that binds at the chromosome origin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:120-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reisenauer, A., C. D. Mohr, and L. Shapiro. 1996. Regulation of a heat shock σ32 homolog in Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 178:1919-1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roberts, R. C., C. Toochinda, M. Avedissian, R. L. Baldini, S. L. Gomes, and L. Shapiro. 1996. Identification of a Caulobacter crescentus operon encoding hrcA, involved in negatively regulating heat-inducible transcription, and the chaperone gene grpE. J. Bacteriol. 178:1829-1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rockabrand, D., T. Arthur, G. Korinek, K. Livers, and P. Blum. 1995. An essential role for the Escherichia coli DnaK protein in starvation-induced thermotolerance, H2O2 resistance, and reductive division. J. Bacteriol. 177:3695-3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ryan, K. R., and L. Shapiro. 2003. Temporal and spatial regulation in prokaryotic cell cycle progression and development. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72:367-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schmidt, K. L., N. D. Peterson, R. J. Kustusch, M. C. Wissel, B. Graham, G. J. Phillips, and D. S. Weiss. 2004. A predicted ABC transporter, FtsEX, is needed for cell division in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186:785-793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schulz, A., B. Tzschaschel, and W. Schumann. 1995. Isolation and analysis of mutants of the dnaK operon of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 15:421-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Segal, G., and E. Z. Ron. 1995. The dnaKJ operon of Agrobacterium tumefaciens: transcriptional analysis and evidence for a new heat shock promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:5952-5958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simão, R. C., M. F. Susin, C. E. Alvarez-Martinez, and S. L. Gomes. 2005. Cells lacking ClpB display a prolonged shutoff phase of the heat shock response in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 57:592-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sun, J., C. G. Savva, J. Deaton, H. R. Kaback, M. Svrakic, R. Young, and A. Holzenburg. 2005. Asymmetric binding of membrane proteins to GroEL. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 434:352-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tamarit, J., E. Cabiscol, and J. Ros. 1998. Identification of the major oxidatively damaged proteins in Escherichia coli cells exposed to oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 273:3027-3032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Teixeira-Gomes, A. P., A. Cloeckaert, and M. S. Zygmunt. 2000. Characterization of heat, oxidative, and acid stress responses in Brucella melitensis. Infect. Immun. 68:2954-2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Teter, S. A., W. A. Houry, D. Ang, T. Tradler, D. Rockabrand, G. Fischer, P. Blum, C. Georgopoulos, and F. U. Hartl. 1999. Polypeptide flux through bacterial Hsp70: DnaK cooperates with trigger factor in chaperoning nascent chains. Cell 97:755-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ullers, R. S., J. Luirink, N. Harms, F. Schwager, C. Georgopoulos, and P. Genevaux. 2004. SecB is a bona fide generalized chaperone in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:7583-7588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Virta, M., S. Lineri, P. Kankaanpaa, M. Karp, K. Peltonen, J. Nuutila, and E. M. Lilius. 1998. Determination of complement-mediated killing of bacteria by viability staining and bioluminescence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:515-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vorderwülbecke, S., G. Kramer, F. Merz, T. A. Kurz, T. Rauch, B. Zachmann-Brand, B. Bukau, and E. Deuerling. 2004. Low temperature or GroEL/ES overproduction permits growth of Escherichia coli cells lacking trigger factor and DnaK. FEBS Lett. 559:181-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang, S. C., and L. Shapiro. 2004. The topoisomerase IV ParC subunit colocalizes with the Caulobacter replisome and is required for polar localization of replication origins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:9251-9256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang, Y., B. D. Jones, and Y. V. Brun. 2001. A set of ftsZ mutants blocked at different stages of cell division in Caulobacter. Mol. Microbiol. 40:347-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ward, D., and A. Newton. 1997. Requirement of topoisomerase IV parC and parE genes for cell cycle progression and developmental regulation in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 26:897-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wood, J. M. 1999. Osmosensing by bacteria: signals and membrane-based sensors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:230-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wright, R., C. Stephens, G. Zweiger, L. Shapiro, and M. R. Alley. 1996. Caulobacter Lon protease has a critical role in cell-cycle control of DNA methylation. Genes Dev. 10:1532-1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wu, J., and A. Newton. 1996. Isolation, identification, and transcriptional specificity of the heat shock sigma factor σ32 from Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 178:2094-2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]