Abstract

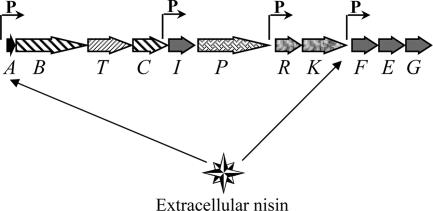

Certain strains of Lactococcus lactis produce the broad-spectrum bacteriocin nisin, which belongs to the lantibiotic class of antimicrobial peptides. The genes encoding nisin are organized in three contiguous operons: nisABTCIP, encoding production and immunity (nisI); nisRK, encoding regulation; and nisFEG, also involved in immunity. Transcription of nisABTCIP and nisFEG requires autoinduction by external nisin via signal transducing by NisRK. This organization poses the intriguing question of how sufficient immunity (NisI) can be expressed when the nisin cluster enters a new cell, before it encounters external nisin. In this study, Northern analysis in both Lactococcus and Enterococcus backgrounds revealed that nisI mRNA was present under conditions when no nisA transcription was occurring, suggesting an internal promoter within the operon. The nisA transcript was significantly more stable than nisI, further substantiating this. Reverse transcriptase PCR analysis revealed that the transcription initiated just upstream from nisI. Fusing this region to a lacZ gene in a promoter probe vector demonstrated that a promoter was present. The transcription start site (TSS) of the nisI promoter was mapped at bp 123 upstream of the nisI translation start codon. Ordered 5′ deletions revealed that transcription activation depended on sequences located up to bp −234 from the TSS. The presence of poly(A) tracts and computerized predictions for this region suggested that a high degree of curvature may be required for transcription initiation. The existence of this nisI promoter is likely an evolutionary adaptation of the nisin gene cluster to enable its successful establishment in other cells following horizontal transfer.

The bacteriocin nisin is naturally produced by some strains of Lactococcus lactis and is able to inhibit most gram-positive bacteria (27). Nisin has long been used as a food preservative because of its antimicrobial properties (14). Recently, nisin has been proposed as a potential alternative antibiotic and also as a good model system for developing peptide antibiotics (6, 25, 38). The genes encoding nisin production and processing, regulation, and immunity are organized in three contiguous operons, i.e., nisABTCIP, nisRK, and nisFEG, located on a large conjugative transposon (16, 18, 19, 28). Transcription of the nisA and nisF promoters is dependent on induction by nisin outside the cell via a two-component regulatory system consisting of NisRK. NisK is the transmembrane histidine kinase that senses nisin and activates NisR by phosphorylation to enable it to induce transcription (31). There is also an alternative induction system for the nisA promoter, which functions independently of the NisRK two-component induction system. Specifically, metabolism of galactose via the Leloir pathway results in an inducer that can initiate nisA transcription from precisely the same start site as transcription initiated by signal transduction with nisin (11).

While the antimicrobial action of nisin has been extensively studied, it is still unclear as to how the nisin immunity system functions to protect the producer cell, especially when it first receives the nisin genes. To kill cells, nisin causes a depletion of the proton motor force. Specifically, nisin physically interacts with lipid II, which is a peptidoglycan precursor, and initiates the formation of a pore structure (5, 6). Although it is not fully clear how the lipoprotein NisI is involved in protection of the producer cell from the action of nisin, some in vitro evidence has suggested that NisI can trap nisin. Purified NisI was shown to bind nisin, but not subtilin, which is a closely related lantibiotic, suggesting that NisI acts as a specific nisin-sequestering protein (45). The mechanism of the ABC transporter NisFEG in protecting the producer cell from nisin was suggested from in vivo studies, where the presence of NisFEG in Bacillus subtilis causes a decrease in the amount of nisin within the cell and an increase of nisin in the supernatant (45). Numerous studies have indicated that the maximum immunity against nisin occurs only when NisI and NisFEG are present, even though either can provide partial immunity. However mutation analyses have shown that NisI plays the dominant role in nisin immunity (28, 40, 44).

When the nisin transposon first enters a cell via conjugation, the nisRK genes are initially expressed via their constitutive promoter, thus setting the two-component induction system in place. Numerous studies have indicated that the nisA promoter is not expressed without induction, suggesting that induction of the nisRK genes occurs following exposure to external nisin or the alternate induction mechanism, galactose metabolism (11, 12, 15, 31). This provides a challenge to the cell to establish sufficient immunity before nisin is produced, and this challenge is even greater because nisI is located at the distal end of the nisABTCIP operon. It would therefore appear to be advantageous if the cell could initially express some basal level of nisI before induction of the nisABTCIP operon, to enable the cell to properly protect itself before nisin is produced or is in the surrounding medium. This possibility was further supported by results with a transconjugant Enterococcus strain N12b (7), which obtained the nisin gene cluster from L. lactis ATCC 11454 and demonstrated immunity to nisin but could not express the nisA promoter (32).

In this study we investigated the possibility of an internal promoter within the nisABTCIP operon that could enable nisI expression before the operon is fully transcribed. The existence of a nisI promoter would help to explain how nisin immunity could be established in the cell before nisin is produced or is added to the surrounding environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Enterococcus sp. strain N12β and L. lactis strains were propagated in M17 (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) broth containing 0.5% glucose (M17G), galactose, or lactose at 30°C without shaking. For RNA isolation, L. lactis ATCC 11454 or Enterococcus strain N12b was grown in 10 ml of M17 medium with 5% glucose at 30°C without shaking to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8. Escherichia coli XL-1 Blue and derivatives were propagated in LB medium (43) at 37°C with shaking. Where needed, erythromycin was added at 150 μg/ml for E. coli and 5 μg/ml for L. lactis, and chloramphenicol was added at 20 μg/ml for E. coli and 5 μg/ml for L. lactis.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Relevant featuresa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli XL-1 Blue | Plasmid-free cloning host | Stratagene |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis ATCC 11454 | Lac+ Suc+ Nip+ Nisr | ATCC |

| L. lactis subsp. cremoris LM0230 | Plasmid-free derivative of L. lactis C2 | 17 |

| Enterococcus sp. strain N12b | Dairy isolate containing the nisin transposon | 7 |

| Micrococcus luteus ATCC 1040 | Bioassay indicator for nisin | ATCC |

| Plasmids | ||

| pTRK390 | Promoter probe plasmid containing a promoterless lacZ reporter gene; Ermr | 37 |

| pDOL0620 | nisI promoter (bp −821 to +220) fused to lacZ in pTRK390; Ermr | This study |

| pDOL0621 | 5′ ordered deletion of pDOL0620 to bp −401; Ermr | This study |

| pDOL0622 | 5′ ordered deletion of pDOL0620 to bp −238; Ermr | This study |

| pDOL0623 | 5′ ordered deletion of pDOL0620 to bp −193; Ermr | This study |

| pDOL0624 | 5′ ordered deletion of pDOL0620 to bp −157; Ermr | This study |

| pDOL0625 | 5′ ordered deletion of pDOL0620 to bp −63; Ermr | This study |

| pDOL0626 | 5′ ordered deletion of pDOL0620 to bp −4; Ermr | This study |

| pDOL0627 | 5′ ordered deletion of pDOL0620 to bp +50; Ermr | This study |

| pDOC23 | nisRK genes cloned into pCI372; Cmr | 12 |

Lac+, lactose metabolism; Suc+, sucrose metabolism; Nip+, nisin production; Nisr, nisin resistance; Ermr, erythromycin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance.

RNA isolation and in vivo detection.

Total RNA was isolated from L. lactis strains according to the protocol of Chandrapati and O'Sullivan (11). Specific RNA transcripts were detected by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) with 1 μg of total RNA as the template. Prior to RT-PCR, total RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase I (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD). SuperScript II (Life Technologies) was used in all RT reactions as per the manufacturer's instructions. Primers used in RT-PCR are listed in Table 2. All PCR amplifications were carried out in a Robocycler (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The PCR conditions for RT-PCR were 94°C for 2 min for 1 cycle; 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min for 30 cycles; and 72°C for 5 min for 1 cycle. All RT reactions were carried out with a duplicate reaction mixture lacking the RT enzyme as a negative control.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Name | Sequencea | EMBL accession no.b | Sequence coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAs | 5′ATGTTACAACCCATCAGAGC3′ | L68307 | 1145-1165 |

| PAa | 5′AGGAGGCACTCAAAATGA3′ | L68307 | 1210-1192 |

| PCs | 5′CAGAGCAATATGAGGATAATG3′ | L16226 | 5221-5241 |

| PCa | 5′GGAGGGAAGAGGAAATGAGAAG3′ | L16226 | 6490-6469 |

| PI1s | 5′ATACTGCGCATGCTCATGCCGGCATTACTCCTCCTGATTATGAC3′ | L16226 | 5633-5654 |

| PI1a | 5′CGGGATCCCGCCTTCGTCAAACCTCACC3′ | L16226 | 6580-6563 |

| PI2s | 5′ATTGTGGCCTTAATAGGG3′ | L16226 | 6504-6521 |

| PI2a | 5′TAGCGACTTGTCAGAAGC3′ | L16226 | 6785-6768 |

| PI3s | 5′CGTGCCACTTTCATCTCCGTATTCTTC3′ | L16226 | 6357-6331 |

| PI3a | 5′CTAATACCTGGACCTCCATAGCACCA3′ | L16226 | 6101-6076 |

| PTs | 5′GAAGAATACATGAAATGAGG3′ | L16226 | 3419-3438 |

| PTa | 5′TAACTTTCCAGCTGTCCC3′ | L16226 | 3721-3704 |

| PZa | 5′TTCTTGAGGAACTTGAGGTGGACGAAGG3′ | M63636.1 | 504-477 |

The underlined sequences represent restriction sites.

Sequence to which the primer sequence coordinates refer.

Measurement of mRNA stability.

A 200-ml volume of a mid-log-phase (OD600, 0.8) L. lactis ATCC 11454 culture was pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in 20 ml of fresh M17 broth containing 0.5% glucose. Rifampin (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO) was added at a final concentration of 0.8 mg/ml from a stock solution in which 50 mg rifampin was dissolved in 1 ml of dimethyl sulfoxide-ethanol (1:1). Immediately, 1.5 ml of culture was removed into an Eppendorf tube and centrifuged for 2 seconds at maximum speed. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. This represented the zero time sample. Further samples were taken at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 min and processed similarly. Total RNA from each sample was isolated as described above and normalized at a concentration of 20 μg/μl. One microliter of total RNA from each sample was spotted on two membranes (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN). The nisA probe was obtained using PCR from L. lactis ATCC 11454 with primers PAs and PAa. The nisI probe was amplified with primers PI1s and PI1a. The positive control for each membrane was 2 μg of unlabeled probe. The PCR conditions were 94°C for 2 min for 1 cycle; 94°C for 20 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 30 s for 30 cycles; and 68°C for 5 min for 1 cycle. Probe labeling and detection were as described by Li and O'Sullivan, (32), except that the hybridization and stringent washing were conducted at 60°C.

Transcription start point determination.

A Smart rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) was adapted to detect transcription start points in L. lactis. To locate the nisI transcription start point on pDOL0620, a reverse lacZ primer was used along with the SmartII primer (Table 2). Two nested reverse nisI primers (Table 2) were used to substantiate the primer extension reaction. The PCR conditions were 95°C for 1 min for 1 cycle; 95°C for 15 s, 68°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min for 35 cycles; and 72°C for 5 min for 1 cycle. PCR products were purified using a QIAGEN PCR purification kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) and sequenced using a reverse nisI primer (Table 2). Sequencing reactions were performed with an ABI Prism Dye Terminator cycle sequencing kit using AmpliTaq DNA polymerase FS, and the products were separated using an ABI 377 automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Cloning techniques.

Standard cloning techniques (43) were used to construct pDOL0620 and derivatives. PCR fragments to be cloned were first purified using a QIAGEN PCR purification kit. Restrictions enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA.) and used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Ligations were performed using a Fast Ligation kit (Epicenter, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Generation of 5′ deletion mutants of the nisI promoter fragment in pDOL0620.

The Erase-A-Base (Promega, Madison, WI) procedure was used to construct ordered 5′ deletions of the nisI promoter fragment in pDOL0620. To protect the vector from exonuclease III digestion, pDOL0620 was restricted with SphI to produce a 3′ extension. It was subsequently digested with NgoMIV to produce a 5′ overhang directly preceding the nisI promoter fragment to permit exonuclease III digestion. Exonuclease III and S1 nuclease digestions and ligations were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Deletion clones were initially selected in E. coli and subsequently introduced into L. lactis by electroporation as described previously (36), using an Eppendorf electroporator (Madison, WI).

Evaluation of DNA curvature.

To evaluate the potential of the upstream region of the nisI promoter to undergo curvature, the DNA curvature program Bent.it, which is based on the BEND algorithm of Goodsell and Dickerson (22), was used. This program can be accessed at (http://hydra.icgeb.trieste.it/∼kristian/dna/bend_it.html). The parameters used were the default DNase I-based bendability parameters (8) and the consensus bendability scale (34).

β-Galactosidase assays.

β-Galactosidase measurements were quantified using the o-nitrophenyl-β-galactoside (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) assay as described by Miller (33). Lactococcal cells were permeated using chloroform, and β-galactosidase measurements were expressed as per OD600 of the culture. In general assays were repeated three times to get the average. However, to analyze the deletion clones, the measurements reported are averaged from 15 replicas.

RESULTS

Analysis of nisA and nisI expression in Enterococcus sp. strain N12b.

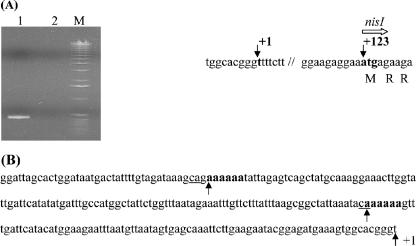

In a previous study we showed that lack of nisin production in the Enterococcus transconjugant strain N12b was due to the absence of nisA transcription (32). However, this strain exhibited significant immunity to nisin, which was estimated to be ∼ 50% of the immunity exhibited by the parental strain, L. lactis ATCC 11454. This suggested the possibility that some immunity may be present prior to the initial exposure to nisin. To investigate this possibility, total RNA from strain N12b was analyzed by RT-PCR to determine if nisI mRNA was present. As expected, no nisA mRNA could be detected, but nisI mRNA was clearly present (Fig. 1A). This indicated that either an alternative promoter within nisABTCIP was likely present to enable expression of nisI in the absence of nisA expression or the nisA transcript was degraded faster than the nisI transcript.

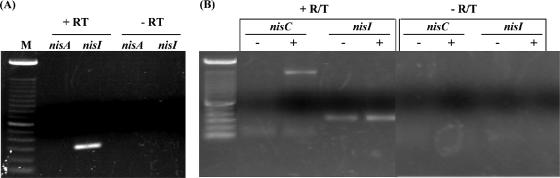

FIG. 1.

(A) Detection of the nisI and nisA transcripts in Enterococcus sp. strain N12b by RT-PCR. R/T, reverse transcriptase. Reaction mixtures without reverse transcriptase were included as negative controls. (B) Detection of the nisI and nisC transcripts in Enterococcus sp. strain N12b by RT-PCR. −, cultures grown without added nisin; +, cultures grown with added nisin to induce nisA transcription; M, 1-kb DNA ladder.

Evaluation of the stability of the nisA and nisI transcripts.

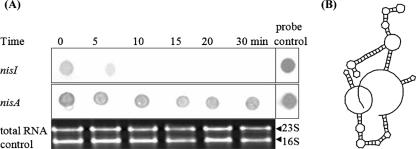

To investigate whether the presence of nisI mRNA was due to rapid degradation of nisA mRNA, the stabilities of the two transcripts were evaluated. Following cessation of transcription activity in L. lactis ATCC 11454, nisI mRNA was observed to degrade, with none visible after 10 min (Fig. 2A). In contrast, nisA mRNA was still largely intact after 30 min, confirming that nisA mRNA was extremely stable. This is consistent with the predicted secondary structure of nisA mRNA, where a large stem-loop structure occurs at the 5′ terminus, which is believed to hinder degradation from the 5′ terminus (Fig. 2B) (41). Immediately downstream from the 3′ terminus there is another stem-loop structure, which can function to further retard degradation of the nisA transcript. Given that the stability of nisA greatly exceeds that of nisI, the presence of nisI mRNA under conditions where nisA is not present can be explained only by an internal nisI promoter.

FIG. 2.

(A) Measurement of nisA and nisI mRNA stabilities by Northern dot blot hybridization. The specificity of both probes has previously been demonstrated (10, 32). Total RNA was extracted at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 min and hybridized with nisA and nisI DNA probes. (B) nisA mRNA secondary structure predicted with GeneQuest (DNAStar, Inc., Madison, WI).

Localization of the promoter region directing nisI expression in Enterococcus sp. strain N12b.

To determine if the promoter directing transcription of nisI in Enterococcus sp. strain N12b was localized directly upstream of nisI or further upstream on the nisABTCIP operon, the presence of mRNA corresponding to nisC was investigated. No nisC mRNA was detected, suggesting that a promoter directly upstream from nisI may be functioning to enable expression of this gene (Fig. 1B). To validate that the experimental conditions were sufficient to detect nisC mRNA, nisin was included in the growth medium to enable transcription of the nisA promoter (32). Under these conditions nisC mRNA could be detected (Fig. 1B). This served as a positive control for the detection of nisC mRNA, confirming that no nisC transcription was occurring in the absence of nisA induction. Similarly, no nisB or nisT mRNA could be detected in the absence of nisA induction (data not shown), indicating that the promoter responsible for nisI induction was likely localized directly upstream from nisI.

Investigation of nisI promoter activity in the original host, L. lactis ATCC 11454.

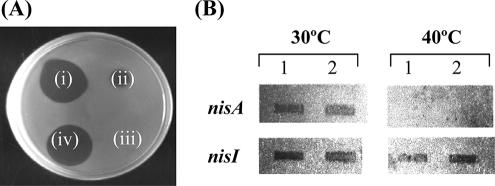

To determine if the observed nisI promoter activity in Enterococcus sp. strain N12b was fortuitous expression due to the heterologous host background or an evolutionary adaptive response of the nisin gene operon, it was necessary to examine its expression in the original L. lactis background. While L. lactis ATCC 11454 is a nisin producer, it has been observed to switch off nisin production during prolonged growth at its maximum growth temperature of 40°C, without loss of the nisin transposon (10). To investigate this further, L. lactis ATCC 11454 was grown at 40°C for ∼25 generations until nisin production could no longer be detected. When the growth temperature was switched to 30°C, full nisin production was restored (Fig. 3A). To evaluate whether the nisA promoter was functioning when nisin production was switched off during growth at 40°C, total RNA was isolated and hybridized with a nisA probe. Unlike cultures grown at 30°C, where ample nisA mRNA could be detected, no nisA mRNA could be detected in the 40°C culture (Fig. 3B). However, hybridization with a nisI probe revealed nisI mRNA to be present in both the 30°C and 40°C cultures (Fig. 3B), confirming that the transcription of nisI in the absence of nisA induction also occurs in its original L. lactis host.

FIG. 3.

(A) Bioassay to detect nisin, using Micrococcus luteus as the indicator strain. i, supernatant from L. lactis ATCC 11454 grown overnight at 30°C; ii, supernatant from L. lactis ATCC 11454 grown overnight at 40°C; iii, supernatant from L. lactis ATCC 11454 grown at 40°C for 25 generations; (iv) supernatant from the 25-generation culture in spot which was subinoculated and grown overnight at 30°C. (B) Northern hybridization of total RNA isolated from L. lactis ATCC 11454 grown at 30°C and at 40°C for 25 generations with either a nisA or a nisI probe. Lanes 1, 1 μg RNA was spotted; lanes 2, 5 μg RNA was spotted.

Fusion of the nisI promoter to a lacZ reporter gene.

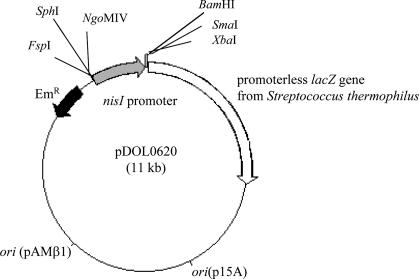

The mRNA analysis indicated that transcription of nisI was initiated at an unknown point upstream from the nisI ATG translation start codon. To further analyze this promoter region, a fragment extending from 944 bp upstream of the ATG start codon to 97 bp downstream was amplified using an upstream primer engineered with an FspI restriction site and a downstream primer engineered with a BamHI site. This fragment was digested with its cognate restriction enzymes and cloned into similarly digested pTRK390, creating the promoter fusion construct pDOL0620 (Fig. 4). Sequencing of the insert region confirmed that no sequence errors from the PCR-based cloning were incorporated. This fusion plasmid is ideally suited to Lactococcus, as its reporter lacZ gene originates from Streptococcus thermophilus, a closely related bacterium with a comparable codon usage. Plasmid pDOL0620 was introduced into L. lactis LM0230 via electroporation, and the inclusion of X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) in the selection plates resulted in blue colonies for pDOL0620, while the control pTRK390 plasmid gave white colonies, confirming promoter activity associated with this fragment in L. lactis. Quantitative β-galactosidase measurements using the o-nitrophenyl-β-galactoside substrate demonstrated reproducible promoter activity from pDOL0620 (78 ± 10 Miller units), while no detectable promoter activity could be detected from the pTRK390 control plasmid.

FIG. 4.

Graphical representation of the nisI promoter fusion plasmid, pDOL0620.

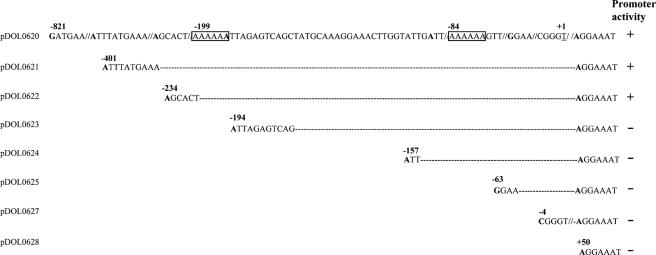

Mapping of the nisI transcription start point.

Having confirmed promoter activity on the cloned nisI promoter fragment, it was necessary to determine the transcription start site (TSS) to further analyze this promoter. Total RNA from L. lactis LM0230 containing pDOL0620 was analyzed using a primer extension procedure, based on a modified RACE methodology. This analysis revealed a TSS at bp −123 upstream of the nisI translation start codon within the C-terminal region of the nisC gene, which overlaps nisI by 4 bp (Fig. 5). An extensive search of promoter databases did not reveal a consensus sequence corresponding to known sigma factors. In L. lactis three sigma factors are known from its genome sequence: the vegetative sigma factor RpoD, the partial competence gene cluster-associated sigma factor ComX, and a possible stress sigma factor, SigX (2). As there were no obvious promoter consensus sequences present, it suggested that other upstream activator sequences may be involved in nisI expression.

FIG. 5.

(A) Mapping of the nisI TSS in pDOL0620 by using the modified primer extension-based RACE methodology. Lane 1, nisI cDNA product; lane 2, negative control, where no reverse transcriptase was added. The TSS is indicated by +1, located 123 bp upstream from the nisI translation start codon (in boldface). (B) Sequence of the upstream region of the nisI promoter. The two poly(A) tracts are in boldface and indicated by arrows. The CA doublets at the 5′ ends of the poly(A) tracts are underlined.

To evaluate whether this may be a processing site downstream from the real TSS, a set of primers upstream from the TSS were designed and tested to see if cDNA could be amplified from the total RNA from L. lactis(pDOL0620). In all cases, cDNA could be amplified only using primers targeting sequences downstream from the TSS, indicating that the mRNA must initiate at the detected TSS and not at a point further upstream (data not show).

Comparison of the regulation mechanisms between the nisI and nisA promoters.

The nisA promoter is positively regulated by induction with nisin, via a two-component induction system, and also independently by induction from a metabolite of galactose metabolism occurring via the Leloir pathway (11). To determine if the nisI promoter is also induced similarly, the effects of galactose and nisin on its transcription were studied. To address the impact of galactose, L. lactis LMO230(pDOL0620) was grown in the M17-galactose and M17-glucose, and β-galactosidase activity was compared over several repetitions. No significant difference in β-galactosidase activity was observed, indicating that growth in galactose did not specifically affect the nisI promoter. To investigate whether the nisI promoter could be induced by nisin via the NisRK two-component regulatory system, plasmid pDOL0620 was introduced into a strain of L. lactis LM0230 carrying nisRK on plasmid pDOC23 (12). As a positive control, the nisA promoter fused to the same lacZ gene in pDOC99 was also introduced into L. lactis LM0230(pDOC23). While the addition of 0.1 to 1.0 IU/ml nisin in the medium showed progressively increasing induction of the nisA promoter, it had no effect on the nisI promoter (data not shown). This confirmed that the expression of the nisI promoter was fully independent of the nisA promoter.

Deletion analysis of the nisI promoter.

To determine the minimum sequence required for expression of the nisI promoter, ordered 5′ deletions of the nisI promoter fragment in pDOL0620 were constructed (Fig. 6). Progressive deletions from bp −821 to −234 with respect to the TSS had no effect on the promoter activity. The promoter activity was abolished when the deletions extended to bp −194. This indicated that this 40-bp region contained sequences necessary for expression of this promoter in L. lactis. Interestingly, this region contains one poly(A) tract (bp −199 to −194), while another is located at bp −84 to −77.

FIG. 6.

Ordered 5′ deletion mutants of the nisI promoter fragment in pDOL0620. The poly(A) tracts are boxed. Plasmids exhibiting promoter activity are indicated by + or −.

To confirm the importance of this 40-bp region, it was necessary to show that the transcription occurring on the smallest, active deletion derivative (pDOL0622) was occurring at the same start point as on the parent plasmid (pDOL0620). Primer extension was employed to compare the TSSs in the deletion derivative L. lactis(pDOL0622) and the original L. lactis(pDOL0620). The two TSSs were identical, positioned at bp −123 relative to the ATG codon. This confirmed that the nisI promoter required sequences located ∼200 bp upstream from the TSS for its expression in L. lactis.

DISCUSSION

The establishment of the nisin gene cluster in a new cell raises the intriguing question of how the cell protects itself when it first encounters nisin in the external medium. This is because both the nisin production and immunity genes are on regulons whose transcription is tightly controlled by signal transduction from external nisin, while the nisRK two-component regulatory system is constitutively transcribed (Fig. 7). One explanation could be that there may be some low-level transcription occurring in the absence of nisin induction. However, the nisA promoter has been extensively studied and is very tightly regulated, with no detectable transcription in the absence of induction (31). Furthermore, if this were the case the cell would be subjecting itself to a race between establishing immunity and producing nisin, and as the nisI gene is located at the distal end of the nisA operon, this would not seem to be an ideal situation. In this study, evidence for an internal promoter within the nisA operon was first obtained when nisI transcripts were detected in both Enterococcus and Lactococcus backgrounds under conditions where no nisA transcription was occurring. Further characterization of this transcription revealed that it was specific to nisI and that a promoter was located upstream of nisI, at the 3′ end of the nisC gene. The existence of this nisI promoter can now explain how a cell can protect itself when it first encounters nisin, and it may be an evolutionary adaptive response of the gene cluster to increase its horizontal mobility.

FIG. 7.

Transcriptional organization of the complete nisin gene cluster, showing the two nisin-inducible promoters and the two constitutive promoters.

For some large operons, in addition to promoters preceding the operon, internal promoters may also be present either in the intercistronic region of genes or in the distal end of a gene. The function of these internal promoters enables the expression of certain distal genes under different physiological conditions (20, 46). Numerous operons have been identified with internal promoters that have a likely physiological role. The ilvGMEDA operon of E. coli contains an internal constitutive promoter that is conserved in many Enterobacteriaceae, pointing to a probable physiological role for its presence (46). Similarly, the E. coli histidine and tryptophan biosynthetic operons have internal promoters controlling the expression of genes at the distal portions of their respective operons, and their existence is not believed to be fortuitous (23, 47). The genes encoding ethanolamine utilization in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium are organized in an operon that includes the gene encoding the transcriptional activator for the operon (eutR). A weak constitutive internal promoter was found to enable eutR expression (42). The identification of a weak constitutive promoter within the nisABTCIP operon is therefore consistent with other operons where a selective advantage existed for its existence. In the case of the nisABTCIP operon, the selective advantage would be to enable the horizontal transfer of the nisin gene cluster into other strains or species and enable the establishment of immunity in the recipient prior to initial exposure to external nisin.

Prokaryotic promoters recognized by the vegetative form of RNA polymerase are generally characterized by two conserved hexamers, 5′-TATAAT-3′ and 5′-TTGACA-3′, generally located about 10 and 35 bp, respectively, upstream of the TSS, with a 17-bp spacer in between. In general, the more consensus the −10 and −35 sequences are, the more active the promoter is (24). However, based on the observation that not many promoters contain strictly consensus sequences, it has long been recognized that in nature promoter activities are optimized rather than maximized (9). This is especially true for many of the known internal promoters within operons. They do not contain consensus −10 and −35 sequences and are weak constitutive promoters (20, 29, 42). In the case of the nisI promoter, the transcription start site has been mapped at bp −123 upstream of the ATG codon. There are no conserved consensus −10 and −35 sequences present, consistent with other weak internal promoters within operons.

Many constitutive promoters require only short regions (∼50 bp) upstream from the TSS for activity. However, a deletion analysis of the nisI promoter revealed that it required up to 234 bp upstream from the TSS, with no activity observed with a deletion extending to bp −194 (Fig. 6). Extended upstream regions of this sort often suggest that activator proteins maybe required to facilitate RNA polymerase binding at poorly defined promoter consensus sequences. This is not always the case, however, as many constitutive promoters with poorly defined consensus RNA polymerase binding sites frequently require extended upstream regions to enable DNA curvature to enhance RNA polymerase binding. A correlation between the intrinsic curvature of a promoter upstream region and the transcription activation has been established for some promoters (3, 4, 13, 21, 26, 39). Short poly(A) tracts appear to be a common signature for this (13, 30), and it is noteworthy that the upstream region of the nisI promoter exhibits two distinctive poly(A) tracts (Fig. 5). One of these is positioned at bp −84, which is consistent with the size and position of the poly(A) tract identified upstream of the nifLA promoter in Klebsiella pneumoniae, which was demonstrated to be required for nifLA promoter activity (13). The other nisI upstream poly(A) tract is positioned at bp −199, and a deletion extending into this tract abolished promoter activity, substantiating its possible involvement. Another signature feature for DNA curvature is the presence of a CA doublet preceding the poly(A) tract (1, 35). Interestingly, both of the poly(A) tracts upstream of the nisI promoter are preceded by a CA. A curvature analysis of the nisI promoter was evaluated using Bent.it, revealing a very high curvature score for the region from bp −216 to −160, which was consistent with the position of the upstream poly(A) tract (bp −199 to −193). This strongly suggests that the activity of this weak constitutive promoter may depend on curvature initiating from a poly(A) tract located 199 bp upstream from the TSS.

In many cases the physiological role for an internal promoter within a multigene operon is not very obvious, as the selective pressure for the evolution of the promoter may not be initially apparent. One case where the selective pressure for an internal promoter is apparent is the eut operon for ethanolamine utilization in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, as the internal promoter is needed to express the transcriptional activator for the whole operon, EutR (42). The selective pressure for the evolution of the internal promoter within the nisin operon is also apparent, as to initially establish the operon in a new cell, it is necessary to express nisI before the nisin structural genes to properly protect the cell from external nisin, which is required to activate transcription of the operon.

Genes encoding antimicrobial compounds and resistance components, such as antibiotic resistance genes, are frequently found on mobile genetic elements, implying that there is evolutionary pressure to disseminate these horizontally in nature. The positioning of the complete nisin gene cluster on a large conjugative transposon is consistent with this reasoning, and the existence of this internal nisI promoter would appear to be a natural adaptation response of the operon to improve its horizontal mobility in nature.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Dairy Management Inc. and the Minnesota Agricultural Experimental Station.

We thank Sailaja Chandrapati for help with the detection of nisI transcripts in L. lactis.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 September 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beutel, B. A., and L. Gold. 1992. In vitro evolution of intrinsically bent DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 228:803-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolotin, A., P. Wincker, S. Mauger, O. Jaillon, K. Malarme, J. Weissenbach, S. D. Ehrlich, and A. Sorokin. 2001. The complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis ssp lactis IL1403. Genome Res. 11:731-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bossi, L., and D. M. Smith. 1984. Conformational change in the DNA associated with an unusual promoter mutation in a tRNA operon of Salmonella. Cell 39:643-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bracco, L., D. Kotlarz, A. Kolb, S. Diekmann, and H. Buc. 1989. Synthetic curved DNA sequences can act as transcriptional activators in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 8:4289-4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breukink, E., H. E. van Heusden, P. J. Vollmerhaus, E. Swiezewska, L. Brunner, S. Walker, A. J. Heck, and B. de Kruijff. 2003. Lipid II is an intrinsic component of the pore induced by nisin in bacterial membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 278:19898-19903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breukink, E., I. Wiedemann, C. van Kraaij, O. P. Kuipers, H. Sahl, and B. de Kruijff. 1999. Use of the cell wall precursor lipid II by a pore-forming peptide antibiotic. Science 286:2361-2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broadbent, J. R., W. E. Sandine, and J. K. Kondo. 1995. Characteristics of Tn5307 exchange and intergeneric transfer of genes associated with nisin production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 44:139-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brukner, I., R. Sanchez, D. Suck, and S. Pongor. 1995. Sequence-dependent bending propensity of DNA as revealed by DNase I: parameters for trinucleotides. EMBO J. 14:1812-1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bujard, H., M. Brenner, U. Deuschle, W. Kammerer, and R. Knaus. 1987. RNA polymerase and the regulation of transcription, p. 95-103. Elsevier Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 10.Chandrapati, S. 2002. Elucidation of regulatory mechanisms effecting nisin biosynthesis in Lactococcus lactis ATCC 11454. Ph.D. thesis. University of Minnesota, St. Paul.

- 11.Chandrapati, S., and D. J. O'Sullivan. 2002. Characterization of the promoter regions involved in galactose- and nisin-mediated induction of the nisA gene in Lactococcus lactis ATCC 11454. Mol. Microbiol. 46:467-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandrapati, S., and D. J. O'Sullivan. 1999. Nisin independent induction of the nisA promoter in Lactococcus lactis during growth in lactose or galactose. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 170:191-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheema, A. K., N. R. Choudhury, and H. K. Das. 1999. A- and T-tract-mediated intrinsic curvature in native DNA between the binding site of the upstream activator NtrC and the nifLA promoter of Klebsiella pneumoniae facilitates transcription. J. Bacteriol. 181:5296-5302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delves-Broughton, J. 1990. Nisin and its use as a food preservative. Food Technol. 44:100-112. [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Ruyter, P. G., O. P. Kuipers, M. M. Beerthuyzen, I. van Alen-Boerrigter, and W. M. de Vos. 1996. Functional analysis of promoters in the nisin gene cluster of Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 178:3434-3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dodd, H. M., N. Horn, and M. J. Gasson. 1990. Analysis of the genetic determinant for production of the peptide antibiotic nisin. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136:555-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Efstathiou, J. D., and L. L. McKay. 1977. Inorganic salts resistance associated with a lactose-fermenting plasmid in Streptococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 130:257-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engelke, G., Z. Gutowski-Eckel, M. Hammelmann, and K. D. Entian. 1992. Biosynthesis of the lantibiotic nisin: genomic organization and membrane localization of the NisB protein. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3730-3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engelke, G., Z. Gutowski-Eckel, P. Kiesau, K. Siegers, M. Hammelmann, and K. D. Entian. 1994. Regulation of nisin biosynthesis and immunity in Lactococcus lactis 6F3. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:814-825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fornwald, J. A., F. J. Schmidt, C. W. Adams, M. Rosenberg, and M. E. Brawner. 1987. Two promoters, one inducible and one constitutive, control transcription of the Streptomyces lividans galactose operon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:2130-2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gartenberg, M. R., and D. M. Crothers. 1991. Synthetic DNA bending sequences increase the rate of in vitro transcription initiation at the Escherichia coli lac promoter. J. Mol. Biol. 219:217-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodsell, D. S., and R. E. Dickerson. 1994. Bending and curvature calculations in B-DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:5497-5503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grisolia, V., A. Riccio, and C. B. Bruni. 1983. Structure and function of the internal promoter (hisBp) of the Escherichia coli K-12 histidine operon. J. Bacteriol. 155:1288-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawley, D. K., and W. R. McClure. 1983. Compilation and analysis of Escherichia coli promoter DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 11:2237-2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffmann, A., U. Pag, I. Wiedemann, and H. G. Sahl. 2002. Combination of antibiotic mechanisms in lantibiotics. Farmaco 57:685-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu, L. M., J. K. Giannini, T. W. Leung, and J. C. Crosthwaite. 1991. Upstream sequence activation of Escherichia coli argT promoter in vivo and in vitro. Biochemistry 30:813-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurst, A. 1981. Nisin. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 27:85-123. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Immonen, T., and P. E. Saris. 1998. Characterization of the nisFEG operon of the nisin Z producing Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis N8 strain. DNA Seq. 9:263-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kofoid, E., C. Rappleye, I. Stojiljkovic, and J. Roth. 1999. The 17-gene ethanolamine (eut) operon of Salmonella typhimurium encodes five homologues of carboxysome shell proteins. J. Bacteriol. 181:5317-5329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koo, H. S., H. M. Wu, and D. M. Crothers. 1986. DNA bending at adenine. thymine tracts. Nature 320:501-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuipers, O. P., M. M. Beerthuyzen, P. G. de Ruyter, E. J. Luesink, and W. M. de Vos. 1995. Autoregulation of nisin biosynthesis in Lactococcus lactis by signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 270:27299-27304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, H., and D. J. O'Sullivan. 2002. Heterologous expression of the Lactococcus lactis bacteriocin, nisin, in a dairy Enterococcus strain. Appl. Environ Microbiol. 68:3392-3400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 34.Munteanu, M. G., K. Vlahovicek, S. Parthasarathy, I. Simon, and S. Pongor. 1998. Rod models of DNA: sequence-dependent anisotropic elastic modelling of local bending phenomena. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23:341-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagaich, A. K., D. Bhattacharyya, S. K. Brahmachari, and M. Bansal. 1994. CA/TG sequence at the 5′ end of oligo(A)-tracts strongly modulates DNA curvature. J. Biol. Chem. 269:7824-7833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Sullivan, D., J., C. Hill, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1993. Effect of increasing the copy number of bacteriophage origins of replication, in trans, on incoming-phage proliferation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:2449-2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Sullivan, D. J., S. A. Walker, S. West, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1996. Development of expression vector technology for Lactococcus lactis using a lytic phage to trigger explosive plasmid amplification and gene expression. Bio/Technology 14:82-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pag, U., and H. G. Sahl. 2002. Multiple activities in lantibiotics—models for the design of novel antibiotics? Curr. Pharm. Des. 8:815-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perez-Martin, J., and M. Espinosa. 1994. Correlation between DNA bending and transcriptional activation at a plasmid promoter. J. Mol. Biol. 241:7-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ra, R., M. M. Beerthuyzen, W. M. de Vos, P. E. Saris, and O. P. Kuipers. 1999. Effects of gene disruptions in the nisin gene cluster of Lactococcus lactis on nisin production and producer immunity. Microbiology 145:1227-1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rauhut, R., and G. Klug. 1999. mRNA degradation in bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 23:353-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roof, D. M., and J. R. Roth. 1992. Autogenous regulation of ethanolamine utilization by a transcriptional activator of the eut operon in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 174:6634-6643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 44.Siegers, K., and K. D. Entian. 1995. Genes involved in immunity to the lantibiotic nisin produced by Lactococcus lactis 6F3. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1082-1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stein, T., S. Heinzmann, I. Solovieva, and K. D. Entian. 2003. Function of Lactococcus lactis nisin immunity genes nisI and nisFEG after coordinated expression in the surrogate host Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:89-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wek, R. C., and G. W. Hatfield. 1986. Examination of the internal promoter, PE, in the ilvGMEDA operon of E. coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 14:2763-2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yanofsky, C., T. Platt, I. P. Crawford, B. P. Nichols, G. E. Christie, H. Horowitz, M. VanCleemput, and A. M. Wu. 1981. The complete nucleotide sequence of the tryptophan operon of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 9:6647-6668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]