Abstract

Endocannabinoids play central roles in retrograde signaling at a wide variety of synapses throughout the CNS. Although several molecular components of the endocannabinoid system have been identified recently, their precise location and contribution to retrograde synaptic signaling is essentially unknown. Here we show, by using two independent riboprobes, that principal cell populations of the hippocampus express high levels of diacylglycerol lipase α (DGL-α), the enzyme involved in generation of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol (2-AG). Immunostaining with two independent antibodies against DGL-α revealed that this lipase was concentrated in heads of dendritic spines throughout the hippocampal formation. Furthermore, quantification of high-resolution immunoelectron microscopic data showed that this enzyme was highly compartmentalized into a wide perisynaptic annulus around the postsynaptic density of axospinous contacts but did not occur intrasynaptically. On the opposite side of the synapse, the axon terminals forming these excitatory contacts were found to be equipped with presynaptic CB1 cannabinoid receptors. This precise anatomical positioning suggests that 2-AG produced by DGL-α on spine heads may be involved in retrograde synaptic signaling at glutamatergic synapses, whereas CB1 receptors located on the afferent terminals are in an ideal position to bind 2-AG and thereby adjust presynaptic glutamate release as a function of postsynaptic activity. We propose that this molecular composition of the endocannabinoid system may be a general feature of most glutamatergic synapses throughout the brain and may contribute to homosynaptic plasticity of excitatory synapses and to heterosynaptic plasticity between excitatory and inhibitory contacts.

Keywords: mGluR5, DSI, GABA, interneuron, LTD, lipid, MGL

Introduction

Molecular, anatomical, and physiological evidence has confirmed critical involvement of the endogenous cannabinoid system in physiological and pathophysiological processes, shedding new light on its molecular components (Piomelli, 2003). Three lipase enzymes were recently identified, which may contribute to the biosynthesis of lipid-derived endocannabinoid substances in the brain. An N-acyl-phosphatidylethanolamine-hydrolyzing phospholipase D was suggested to be responsible for the synthesis of the firstly discovered endocannabinoid anandamide (Devane et al., 1992; Okamoto et al., 2004), whereas two closely related sn-1-specific diacylglycerol lipases (DGL-α and DGL-β) were proposed to mediate the formation of another endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol (2-AG) (Mechoulam et al., 1995; Sugiura et al., 1995; Bisogno et al., 2003). Among several molecular targets potentially activated by endocannabinoids (Begg et al., 2005), two G-protein-coupled receptors, CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors, have emerged as key elements of the endocannabinoid system (Matsuda et al., 1990; Munro et al., 1993). Finally, elimination of the endocannabinoids is performed by a two-step process consisting of carrier-mediated internalization (Beltramo et al., 1997; Hillard et al., 1997; Fegley et al., 2004), followed by intracellular hydrolysis catalyzed by fatty-acid amide hydrolase and monoacylglycerol lipase (MGL) for anandamide and 2-AG, respectively (Cravatt et al., 1996; Dinh et al., 2002).

A major physiological role of the endocannabinoid system is the regulation of neurotransmitter release at various types of synapses throughout the brain (Freund et al., 2003). Endocannabinoids are lipid-derived messengers that are thought to be produced postsynaptically on demand and evoked by specific physiological stimuli, but they are proposed to act presynaptically on cannabinoid receptors (Alger, 2002; Wilson and Nicoll, 2002). This reverse mode of action makes them ideal candidates as retrograde signals in several paradigms of short- and long-term synaptic plasticity (Chevaleyre et al., 2006). Most forms of synaptic plasticity require precise timing on the millisecond timescale and are strictly localized into subcellular microdomains such as dendritic spines in the case of glutamatergic synapses. It is widely believed that several forms of synaptic plasticity in this latter type of synapse use endocannabinoids (for review, see Gerdeman and Lovinger, 2003; Diana and Marty, 2004); however, the underlying molecular composition of the endocannabinoid system and its spatial organization remain speculative.

To understand how the endocannabinoid system contributes to synaptic plasticity at glutamatergic synapses, it is essential to localize the exact site of synthesis of these compounds, identify the enzymes responsible for their formation, define their molecular substrates, and, finally, determine their primary sites of action. In the hippocampus, 2-AG may be the main endocannabinoid involved in synaptic plasticity (Stella et al., 1997; Makara et al., 2005; Straiker and Mackie, 2005). Here we show that DGL-α, a synthetic enzyme for 2-AG, is expressed by hippocampal principal cells and is strikingly concentrated in dendritic spine heads within a perisynaptic annulus encircling the postsynaptic density of excitatory synapses. Furthermore, we provide direct anatomical evidence that these glutamatergic synapses are formed by axon terminals bearing presynaptic CB1 receptors. This specific molecular anatomical architecture provides the basis for 2-AG as a retrograde signaling molecule at glutamatergic synapses.

Materials and Methods

Perfusion and preparation of tissue sections.

Experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the institutional ethical code and the Hungarian Act of Animal Care and Experimentation (1998, XXVIII, Section 243/1998.). Adult male C57BL/6H mice (12 wild type, 61 ± 13 d old) and CD1 mice (three wild type and three CB1 knock-out, all 57 d old) (Ledent et al., 1999) were deeply anesthetized with Equithesin (4.2% w/v chloral hydrate, 2.12% w/v MgSO4, 16.2% w/w Nembutal, 39.6% w/w propylene glycol, and 10% w/w ethanol in H2O; 0.3 ml/100 g, i.p.) then perfused with Zamboni's fixative containing 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4 (eight C57BL/6H mice, and the three wild-type and three knock-out CD1 mice). Animals were perfused transcardially, first with 0.9% saline for 2 min, followed by 100 ml of Zamboni's fixative for 20 min. An additional two mice were perfused using the same fixative but with 0.1% glutaraldehyde. Another two mice were processed for a sequential low pH/high pH perfusion (Berod's fixative). In these cases, the saline was followed by the first component of Berod's fixative, pH 6, for 5 min and the second component of Berod's fixative for 50 min, pH 8.5. After perfusion, the brain was removed from the skull, and coronal sections (40 μm thick for in situ hybridization and 50 μm thick for immunocytochemistry) containing the hippocampus and the entire forebrain at the level of the dorsal hippocampus were cut with a Leica (Nussloch, Germany) VTS-1000 vibratome.

Synthesis of riboprobes for DGL-α.

Two nonoverlapping sections of the mouse DGL-α coding sequence (see Fig. 1A) (GenBank accession number gi:33390900) were amplified by reverse transcription-PCR from cDNA derived from total C57BL/6H mouse frontal cortex mRNA. The length and the sequence of primers are listed below for both probes; numbering of the nucleotide positions starts from the beginning of the open reading frame: probe 1, 598 bp from 1184 to 1782 (forward primer, 5′-TCA TGG AGG GGC TCA ATA AG; reverse primer, 5′-CTA GCG TGC CGA GAT GAC CA); probe 2, 1169 bp from 1967 to 3135 (forward primer, 5′-TCA GTA TCC GGG GAA CAC TG; reverse primer, 5′-AGG GCG ATG GTC AAA TCA CT). The primers were designed using the Primer3 software (Rozen and Skaletsky, 2000). PCR products were cloned into the SmaI site of pBluescript II SK− (Fermentas UAB, Vilnius, Lithuania). The integrity and orientation of clones were verified by sequencing. Probe 1 was linearized by BamHI and Eco32I digestion for the antisense and sense probe, respectively. Probe 2 was linearized by EcoRI and BamHI digestion for the antisense and sense probe, respectively. The linearized template DNA was gel extracted, precipitated, resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated H2O at a concentration of 1 μg/μl, and stored at −20°C. In vitro transcription was performed for 2 h at 37°C in a total volume of 20 μl containing 1 μg of template DNA, 1× transcription buffer, 1× digoxigenin RNA labeling mixture, 40 U of RNase inhibitor, and 20 U of T3 or T7 RNA polymerase, which was adjusted to 20 μl using DEPC-free double-distilled H2O. All components were from Roche Molecular Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany). Labeled riboprobes were DNase treated and purified using the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Finally, the integrity and quantity of the riboprobes were determined using gel electrophoresis.

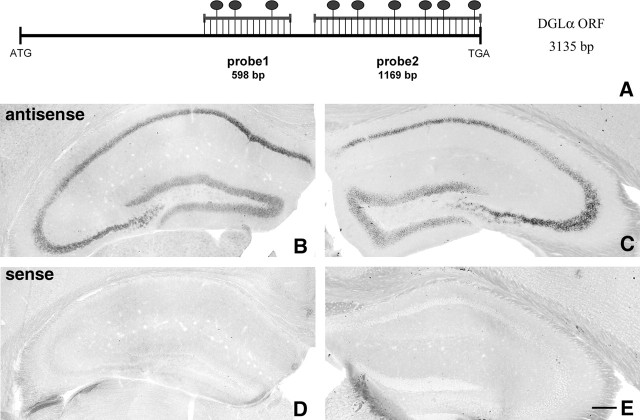

Figure 1.

Principal cells express high levels of DGL-α mRNA in the hippocampus. A, Schematic representation of the positions of the two complementary antisense riboprobes on the sequence of the mouse DGL-α mRNA. The length of the open reading frame (ORF) on the DGL-α mRNA is 3135 bp long. The ATG codon indicates the translation initiation site on the sequence and represents position 1–3 in the numbering, whereas TGA is the stop codon (position 3133–3135). The dark ovals above the duplex scheme indicate the predicted frequency of digoxigenin-labeled nucleotides in the ratio of the total length of the probes, which were 598 and 1169 bp in the case of probe 1 and probe 2, respectively. B, C, In situ hybridization by using the two antisense probes illustrated in A visualizes the principal cell layers of the mouse hippocampus. The expression level is very high in the CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons and somewhat weaker, but still high, in the granule cells of the dentate gyrus. In contrast, neither GABAergic interneurons nor glial cells are labeled by the probes under these reaction conditions, indicating much weaker expression or a complete absence of DGL-α in these cell types. Note the identical labeling by the two riboprobes, which confirms the specificity of the signal. D, E, In contrast, in situ hybridization using the sense riboprobes derived from the corresponding DGL-α sequence do not result in any labeling. Scale bar, 200 μm (for B–E).

In situ hybridization. All solutions used for in situ hybridization were first treated with 0.1% DEPC for 1 h and then autoclaved. Chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Budapest, Hungary), if otherwise not indicated. Incubation of the 40-μm-thick brain slices was performed in a free-floating manner in RNase-free sterile culture wells for all steps. First, the sections were washed in PBST (containing 137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 10 mm Na2HPO4, 2 mm KH2PO4, and 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.4) three times for 20 min. Hybridization was then performed overnight at 65°C in 1 ml of hybridization buffer containing the digoxigenin-labeled riboprobe (2.5 μg/ml). Hybridization buffer consisted of 50% formamide, 5× SSC, 1% SDS, 50 μg/ml yeast tRNA, and 50 μg/ml heparin in DEPC-treated H2O. During the overnight incubation and the following three washing steps, the sections were continuously incubated on a shaker within a humid chamber. After incubation, the sections were first washed for 30 min at 65°C in wash solution 1 (containing 50% formamide, 5× SSC, and 1% SDS in DEPC-treated H2O) and then twice for 45 min at 65°C in wash solution 2 (containing 50% formamide and 2× SSC in DEPC-treated H2O). The section were next washed for 5 min in 0.05 m Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST), pH 7.6, and then blocked in TBST containing 10% normal goat serum (TBSTN) for 1 h, both at room temperature. Next, sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with sheep anti-digoxigenin Fab fragment conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Roche Molecular Diagnostics) diluted at 1:1000 in TBSTN. The next day, the sections were washed three times for 20 min in TBST and then developed with freshly prepared chromogen solution in a total volume of 10 ml, containing 3.5 μl of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate and 3.5 μl of nitroblue-tetrazolium-chloride dissolved in chromogen buffer (containing mm 100 NaCl, 100 mm Tris-Cl, pH 9.5, 50 mm MgCl2, 2 mm (−)tetramisole hydrochloride, and 0.1% Tween 20). The sections were gently rinsed in 1 ml of the above developing solution in the dark for 4–6 h, and the reaction was stopped using PBST. Finally, the sections were washed in 0.1 m PB three times for 10 min and mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories Burlingame, CA) onto glass slides, and the coverslips were sealed with nail polish.

Preparation of antibodies for DGL-α.

Two polyclonal antibodies were raised in rabbits against glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins containing residues 790–908 or 1016–1042 of human DGL-α (see Fig. 2A). Rabbits were immunized, and serum was collected at 3 week intervals. Immune serum was purified by sequential affinity chromatography: the flow-through from a GST column was applied to a fusion protein column, and the antibody was eluted with 0.2 m glycine. After neutralization with 1 m Tris base, antibodies were dialyzed against PBS containing 50% glycerol and stored at −20°C until use. Antibody specificity was established by staining HEK293 cells transiently expressing a V5 epitope-tagged DGL-α with either purified antibody or purified antibody preincubated with 5 μg/ml immunizing protein. Preincubation with the immunizing protein strongly attenuated staining by the DGL-α antibody but not by the epitope tag antibody. In brain sections, the two antibodies revealed a similar immunostaining pattern (see Results and Figs. 2C,D, 3B,C, 4B,C), which was eliminated by pretreatment with the corresponding immunizing protein.

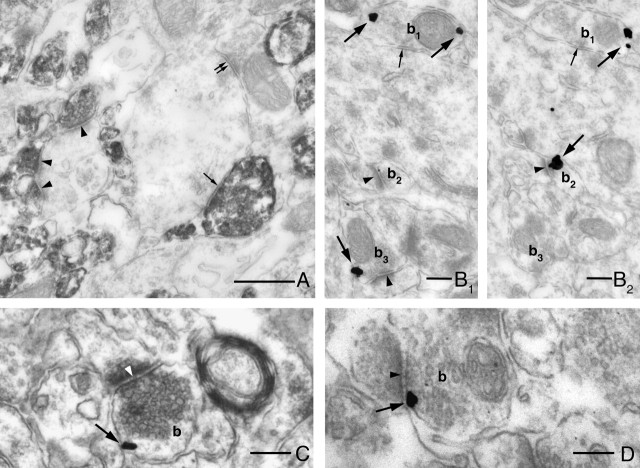

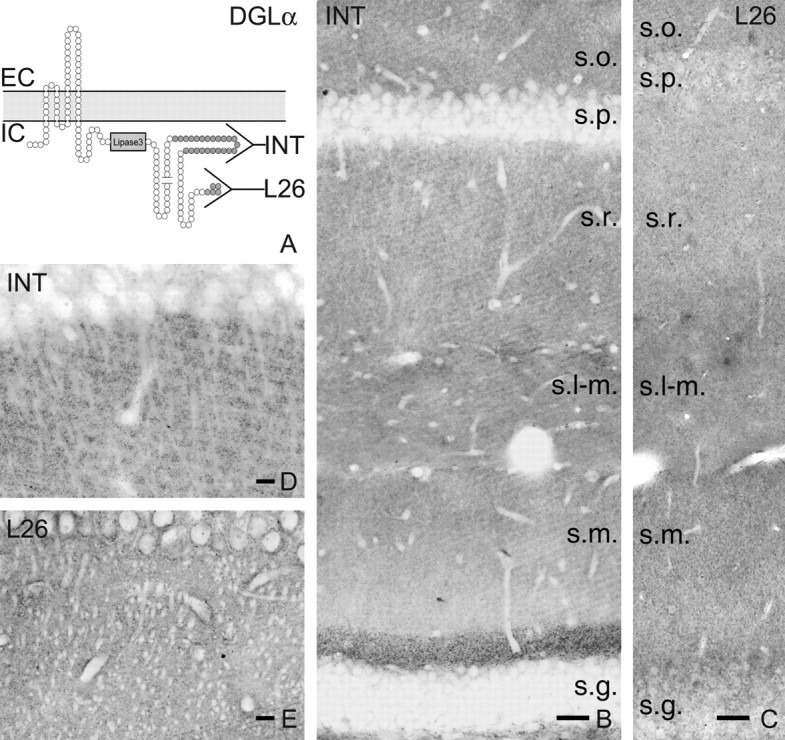

Figure 2.

Localization of DGL-α protein in the hippocampus. A, Schematic representation of the predicted transmembrane topology of the DGL-α enzyme. Predicted SMART (simple modular architecture research tool) analysis suggests that DGL-α has four transmembrane domains and a long intracellular C-terminal tail, which contains a lipase3 domain thought to be critical for 2-AG synthesis. The two antibodies against two nonoverlapping segments of the C-terminal tail are indicated by the horizontal Y shapes. The epitope for antibody “INT” is a 118 residue stretch, whereas for “L26” it is the last 26 amino acids on the C terminus. EC and IC label the extracellular and intracellular side of the plasma membrane, respectively. B, Immunocytochemistry for DGL-α delineates the layered structure of the hippocampus, which is determined by the topography of excitatory pathways. The strongest labeling is visible in the inner third of stratum moleculare (s.m.), but generally the staining is denser in the CA1 subfield than in the remainder of the dentate gyrus. Strata oriens (s.o.) and radiatum (s.r.) also has a high density of DGL-α immunoreactivity, whereas immunostaining in the stratum lacunosum-moleculare (s-l.m.) appears more modest. Remarkably, in contrast to the dense labeling in the dendritic layers, cell bodies of both the pyramidal cells in stratum pyramidale (s.p.) as well as the granule cells in stratum granulosum (s.g.) are only faintly labeled, indicating that the DGL-α protein is targeted out to neural processes after synthesis in the cytoplasm. C, On the whole, a similar but significantly weaker labeling pattern is visible using the L26 antibody for immunostaining. D, E, At higher magnification, the main apical dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons appear to be immunonegative and are outlined by a very dense punctuated immunostaining pattern. Note the nearly identical labeling by the two antibodies, confirming the specificity of the antibodies. Scale bars: B, C, 50 μm; D, E, 20 μm.

Figure 3.

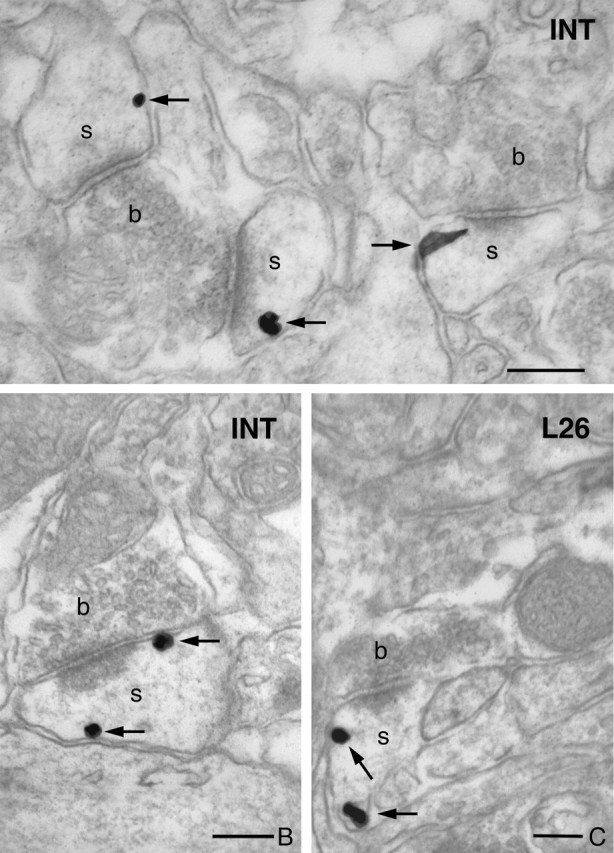

DGL-α immunolabeling is concentrated in the head of dendritic spines in the hippocampus. A, Low-power electron micrograph of DGL-α immunostaining in the stratum oriens of the CA1 subfield visualizes numerous dendritic spines (depicted by s) containing the dense end product of the immunoperoxidase reaction (DAB). These DGL-α-containing spines receive asymmetrical synapses from DGL-α-negative boutons (b). Note the rather selective localization of immunoreactivity within the spines and its absence in other neuronal and glial processes. B, C, In case of tangentially sectioned spines, in which the neck, the base, and the corresponding dendritic shaft are also visible in the same plane as the head, the immunoreactive material indicating the localization of DGL-α shows a highly compartmentalized distribution limited to the spine head. These spines (s) also receive a single asymmetrical synapse onto the top of the spine head by DGL-α-negative axon terminal (b). Note the similar distribution profiles of the immunoreactive material by the two antibodies, “INT” and “L26,” confirming their specificity. Scale bars: A–C, 0.2 μm.

Figure 4.

DGL-α is present on the plasma membrane in the head of hippocampal dendritic spines. A, High-resolution preembedding immunogold staining for DGL-α demonstrates that this lipase is present on the plasma membrane of dendritic spines. In this high-power electron micrograph, the three dendritic spines (s) receive an asymmetrical synapse from two axon terminals (b). The characteristic electron-dense postsynaptic density of the synaptic specialization indicates that these are excitatory glutamatergic synapses. B, C, High-power electron micrograph showing immunogold staining for DGL-α in stratum radiatum of CA1. Note that the gold particles (arrows) representing the precise subcellular localization of DGL-α are always attached to the intracellular surface of the plasma membrane in accordance with the predicted position of the epitopes of the DGL-α protein, confirming the specificity of the two antibodies. Furthermore, these micrographs demonstrate the entirely similar distribution pattern for both the “INT” and “L26” antibodies at the subcellular level. Scale bars: A–C, 200 μm.

Immunocytochemistry.

After slicing and extensive washing in 0.1 m PB, the 50-μm-thick sections were incubated in 30% sucrose overnight, followed by freeze thawing over liquid nitrogen four times. Afterward, the sections were processed for immunoperoxidase, immunogold, or preembedding immunogold staining combined with a second immunoperoxidase staining. Subsequently, all washing steps and dilutions of the antibodies were done in 0.05 m TBS, pH 7.4. After extensive washing in TBS, the sections were blocked in 5% normal goat serum for 45 min and then incubated in one of the two affinity-purified rabbit anti-DGL-α (1:1000–1:3000; ∼0.3–1 μg/ml) antibodies or guinea pig anti-CB1 (1 μg/ml) (a gift from Prof. M. Watanabe, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan) (described by Fukudome et al., 2004) for a minimum of 48 h at 4°C. The specificity of the latter antibody was confirmed by the lack of immunostaining in CB1 knock-out mice (Ledent et al., 1999). In this control experiment, sections from wild-type and knock-out animals were mixed in the incubation wells and processed together throughout the reaction. In the immunoperoxidase staining procedure, after primary antibody incubations, the sections were treated with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (1:300) or with biotinylated anti-guinea pig IgG (1:300), both raised in goat, for 2 h and then with avidin biotinylated–horseradish peroxidase complex (1:500; Elite ABC; Vector Laboratories) for 1.5 h. The immunoperoxidase reaction was developed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as the chromogen. In the immunogold staining procedure, the sections were incubated in 0.8 nm gold-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-guinea pig antibody for CB1 or DGL-α, respectively (1:50 dilution; Aurion, Wageningen, The Netherlands), overnight at 4°C. Then the sections were silver intensified using the silver enhancement system R-GENT SE-EM according to the kit protocol (Aurion). In the double-immunostaining experiments, the sections were first developed for immunogold and then for immunoperoxidase staining. Lack of cross-reactivity of the secondary antibodies in the sequential detection scheme was verified by omission of either primary antibody, which eliminated labeling by the irrelevant secondary antibody.

After development of the immunostaining, the sections were treated with 1% OsO4 in 0.1 m PB for 20 min, dehydrated in an ascending series of ethanol and propylene oxide, and embedded in Durcupan (ACM; Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland). During dehydration, the sections were treated with 1% uranyl acetate in 70% ethanol for 20 min. From sections embedded in Durcupan, areas of interest were reembedded and resectioned for electron microscopy. Sections were collected on Formvar-coated single-slot grids, stained with lead citrate, and examined with a Hitachi (Yokohama, Japan) 7100 electron microscope.

Quantitative analysis of the distribution of DGL-α in the head of dendritic spines.

To establish the precise subsynaptic or extrasynaptic distribution of DGL-α within the pyramidal spines, we performed a high-resolution quantitative evaluation in a population of 300 immunogold-labeled dendritic spine heads from three animals. Samples for electron microscopic analysis were taken from the stratum radiatum of the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus. Superficial ultrathin sections were collected (first 5–10 μm) because immunoreactivity decreased with depth. To be able to compare the mean distribution of DGL-α along the plasma membrane surface of dendritic spine heads with the mean distribution of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 (mGluR5), we followed the analysis procedure of Lujan and colleagues (for details, see Lujan et al., 1996, 1997). Briefly, the length of spine membrane from the edges of the synaptic junction was measured for every DGL-α-positive spine and was divided into 60 nm bins. The localization of the gold particles representing DGL-α was measured as the distance between the closest edge of the postsynaptic density and the center of the immunoparticles present on the plasma membrane of the spines. The three samples were compared using Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test, and data are presented as mean ± SD. Because the samples from the three animals did not differ significantly (see Results), data were pooled and expressed as the proportion of gold particle-containing plasma membrane divisions. In addition, we also analyzed the same dataset after normalization for the frequency of plasma membrane segments measured in the same population of spine heads.

Lujan and colleagues performed their thorough analysis in rats, whereas we performed our experiments in C57BL/6H mice. The published mean synaptic membrane specialization length (measured along the largest extent in the plane of sections that randomly cut the synapse) on the spine heads in rats (189.6 ± 52.1 nm) was similar to the range of values we obtained in mice (223.5 ± 47 nm). Therefore, we believe that the two spine populations used for analysis in the two studies allows comparing the distribution of these two functionally related molecules along the surface of the spines and in relation to neurotransmitter release sites.

Results

DGL-α mRNA is highly expressed by principal cells in the hippocampus

Previous work suggested that DGL-α may be the main synthetic enzyme for 2-AG in the adult brain (Bisogno et al., 2003). To determine the cellular expression pattern of DGL-α in the mouse hippocampus, we prepared two independent digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes against the mouse DGL-α sequence corresponding to two nonoverlapping sequences (Fig. 1A). Nonradioactive free-floating in situ hybridization on mouse forebrain sections revealed a similar distribution pattern with both antisense riboprobes but showed no significant labeling with two control sense probes (Fig. 1B–E). Highest DGL-α expression was observed in the hippocampus, in which the principal cell layers were characteristically visualized by the staining (Fig. 1B,C). Pyramidal neurons in the CA3 and CA1 subfields were always more strongly labeled than dentate gyrus granule cells. Weakly labeled cells were scattered in the hilus of the dentate gyrus; these cells may correspond to the so-called mossy cells, glutamatergic interneurons of the dentate gyrus, or GABAergic interneurons. Neither interneurons in other layers nor glial cells were found to express DGL-α. Conversely, we must note that the in situ hybridization reactions were performed under highly stringent conditions to avoid any nonspecific labeling, which may have resulted in reduced sensitivity. Nevertheless, we can conclude that glutamatergic principal cell types express DGL-α at a very high level. DGL-α mRNA expression was also observed in other principal cell types of the forebrain at a lower level. A more detailed characterization of the regional and cellular expression pattern of DGL-α is currently underway (I. Katona et al., unpublished observations).

DGL-α is concentrated in dendritic spine heads of principal cells in the hippocampus

To study the precise subcellular localization of DGL-α, we developed two independent polyclonal antibodies against nonoverlapping epitopes on the C terminus of DGL-α (Fig. 2A). The first antibody recognized a large intracellular loop (ab-INT), whereas the second antibody was raised against the last 26 amino acids of DGL-α (ab-L26) (Fig. 2A). The pattern of immunostaining with the two antibodies was similar at both the light microscopic and electron microscopic levels (Fig. 2B–D), although the general density of staining was much stronger for ab-INT and the labeled profiles were much sparser for the ab-L26. At low magnification, the layered structure of the hippocampus corresponding to the termination zone of certain glutamatergic pathways was evident (Fig. 2B). Similar to the mRNA distribution, the CA1 and CA3 subfields were generally more strongly labeled, especially the stratum oriens and stratum radiatum, whereas the labeling was somewhat fainter in the stratum lacunosum-moleculare. In contrast, the dentate gyrus showed somewhat fainter immunostaining, except the inner third of the molecular layer, which was also strongly immunoreactive for DGL-α (Fig. 2B). At higher magnification, a dense punctuated immunostaining was visible throughout the neuropil (Fig. 2D,E). This characteristic staining pattern outlined major dendritic shafts and cell bodies, which were only very faintly immunopositive, if at all. Neither interneuronal nor glial processes were observed to be immunostained in these sections. Immunostaining for DGL-α in other forebrain areas, including the neocortex and the basolateral amygdala, revealed a similar punctate staining pattern (data not shown).

To determine which subcellular domains might underlie this characteristic staining pattern at the light microscopic level, we performed a detailed electron microscopic analysis. Samples taken from most layers of all three major subfields of the hippocampus revealed the same staining pattern with either antibody. The DAB end product of the immunoperoxidase staining procedure, which indicates the subcellular localization of DGL-α, was concentrated in a large number of dendritic spine heads (Fig. 3A). Notably, although DAB gives rise to a diffusible reaction end product, it did not fill the entire spine head (Fig. 3B,C). Instead, in most cases, it was unevenly distributed along the plasma membrane. Although we tried several fixation protocols and antibody dilutions and our ultrathin sections were collected from the upper 5 μm of the stained sections, we could not achieve the labeling of every spine head in our samples. This may either reflect the existence of dendritic spines that lack DGL-α or it can be simply explained by the possibility that the level of DGL-α in these immunonegative spines is below the detection threshold of our antibodies. This second possibility is supported by the observation that the more sensitive ab-INT always visualized a higher ratio of DGL-α-positive dendritic spines than ab-L26. Nevertheless, in most cases, the ratio of DGL-α-containing spines was above 50% with either antibody, and, in random samples from the strata radiatum and oriens, >80% of spines were positive for DGL-α. Because the ratio of immunopositive spines is strongly dependent on the success of fixation, the penetration of the antibody and several other unknown factors such as masking the epitope by other interacting proteins, a precise quantification is not feasible. Nevertheless, although we cannot exclude the possibility that every spine contains some DGL-α, we consider that the 50% ratio should be regarded as the absolute minimum estimate. In contrast to the strong labeling at glutamatergic synapses, none of the antibodies revealed consistent labeling at sites postsynaptic to GABAergic boutons or in other postsynaptic subcellular domains. However, these negative findings may be subject to the same limitations discussed above.

DGL-α is concentrated in a characteristic perisynaptic annulus around the postsynaptic density at glutamatergic synapses

Although dendritic spines are specialized microdomains themselves, recent studies have revealed that they are subdivided into discrete morphological and functional units, which contribute to distinct aspects of synaptic signaling and plasticity. Therefore, we used the resolving power of the silver-enhanced immunogold technique to obtain additional insights and predictions about the potential functional role of DGL-α at the subsynaptic and molecular level. Immunogold labeling by either antibody revealed the same pattern as immunoperoxidase staining, gold particles indicating that the precise localization of DGL-α were flocked in the heads of dendritic spines (Fig. 4A). Remarkably, these immunogold particles were nearly always attached to the intracellular side of the plasma membrane. This is in accordance with the spatial position of the epitopes on the DGL-α protein, which has four transmembrane domains and whose C terminus is intracellular (Fig. 2A), providing additional support for the specificity of the two antibodies (Fig. 4B,C).

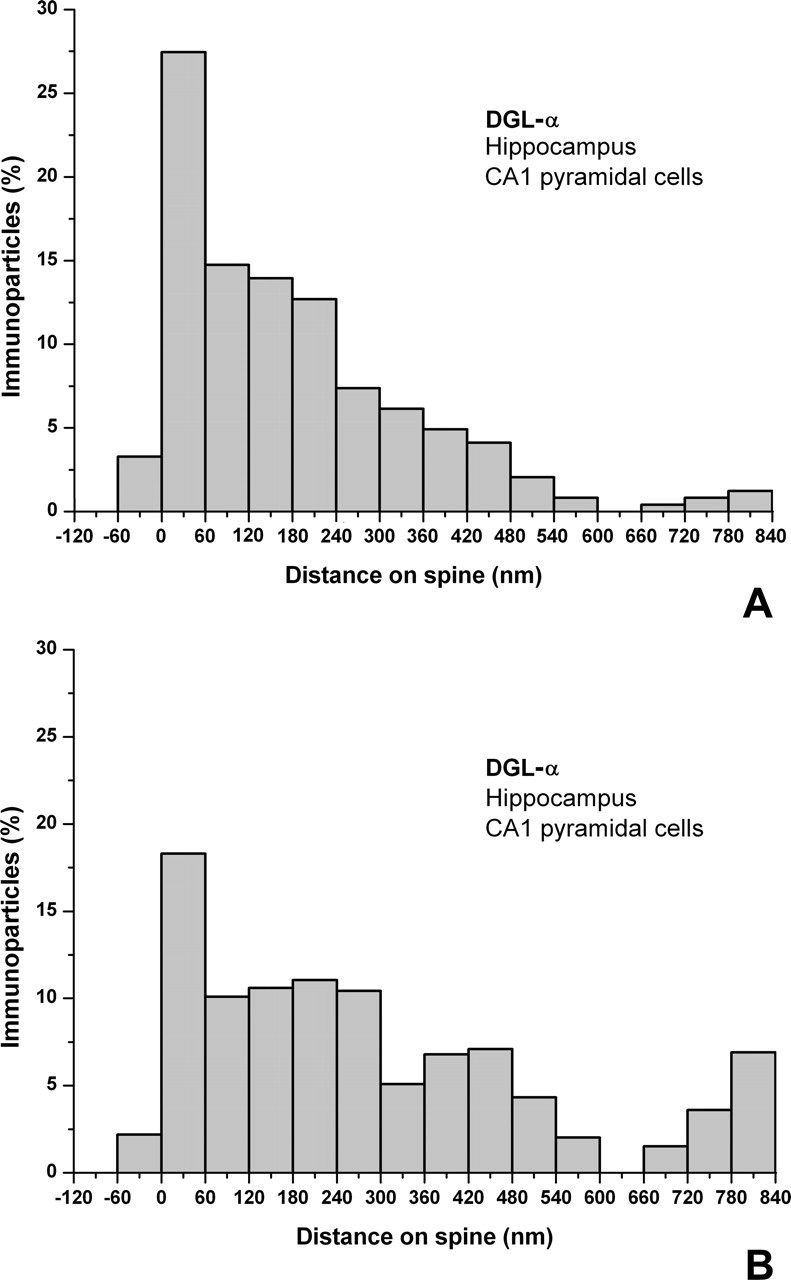

To further determine the subsynaptic distribution of DGL-α, we took a random sample of 300 glutamatergic synapses (100 from each of three animals; Kruskal–Wallis test revealed a homogenous population, p = 0.13; therefore, the samples were pooled) from stratum radiatum of the CA1 subfield and quantified the precise position of the gold particles in relation to the postsynaptic density. We followed exactly the published analytical procedure of Lujan and colleagues (Lujan et al., 1996, 1997) (for additional details, see Materials and Methods), who described the subsynaptic distribution of mGluR5 to be able to compare its distribution with DGL-α. This quantitative analysis revealed that nearly every gold particle was attached to the plasma membrane on the postsynaptic side of the glutamatergic synapses (91 ± 2%). Additional quantification of the subsynaptic distribution pattern uncovered that the highest density of DGL-α occurs in a characteristic perisynaptic annulus around the postsynaptic density with an extrasynaptic gradient decreasing toward the spine neck (Fig. 5). When the distances are divided into 60 nm bins, the highest peak of the density of gold particles is concentrated within the first 60 nm bin from the edge of the postsynaptic density (27 vs 18% in core vs normalized distributions, respectively), whereas most of the labeling is found on the plasma membrane within the 300 nm from the edge of the postsynaptic density (75 vs 62% in core vs normalized distributions, respectively). Farther away, the labeling frequency was diluted out in the direction of the spine neck. One must also note that DGL-α was only very rarely observed intrasynaptically (3 vs 2% in core vs normalized distributions, respectively). Remarkably, this characteristic perisynaptic distribution in an annulus closely parallels the subcellular distribution reported for mGluR5 within the same synapses in stratum radiatum of the CA1 subfield (0% intrasynaptic; ∼25% in the 60-nm-wide annulus) (Lujan et al., 1996, 1997).

Figure 5.

Distribution of DGL-α is highly compartmentalized on the head of the dendritic spines. A, B, Spatial distribution of immunogold particles representing DGL-α in relation to glutamate release sites on spine heads (n = 300) of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells in the stratum radiatum. The distance of immunogold particles from the edge of the synaptic junction (position 0, indicated by arrows) was measured along the plasma membrane, which was divided into 60 nm bins. Data are expressed as the percentage of immunogold particles in a given bin compared with all gold particles found in the spines. In A, the core dataset is illustrated, whereas in B, the same dataset was normalized to the frequency of given membrane compartments within the same spine population. The measurements demonstrate that DGL-α is preferentially targeted to a perisynaptic ring around the synaptic specialization but almost entirely excluded from the synapse itself. Besides a perisynaptic pool, the distribution of extrasynaptic DGL-α shows a clear gradient, decreasing toward the spine neck.

Presynaptic CB1 cannabinoid receptors are localized on glutamatergic axon terminals in the hippocampus

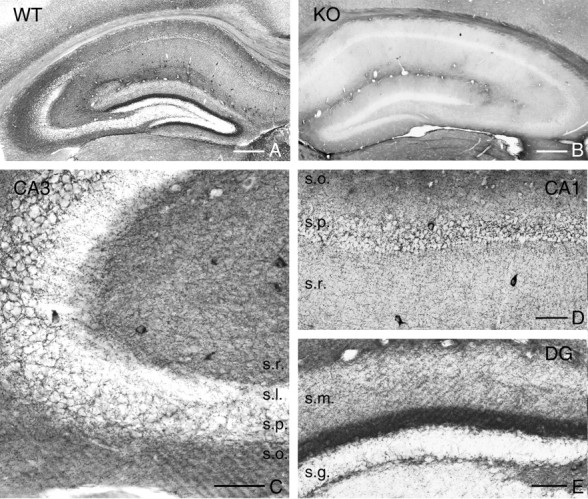

The peculiar localization of DGL-α, the main synthesizing enzyme for 2-AG, on the head of dendritic spines receiving excitatory, glutamatergic synapses predicts the presence of nearby CB1 receptors, which may be targeted by 2-AG. Indeed, although the presynaptic effect of cannabinoids on glutamate release is well documented, the molecular identification of the receptors involved is still ambiguous (Hájos et al., 2001; Ohno-Shosaku et al., 2002b) and was demonstrated to be species or strain dependent (Hoffman et al., 2005). Previous immunocytochemical analyses provided unequivocal evidence for the presence of CB1 receptors on a select subset of hippocampal GABAergic boutons using knock-out animals to demonstrate the specificity of the antibodies (Hájos et al., 2000). In contrast, although CB1 mRNA is expressed at a low level in CA3 and CA1 pyramidal cells, the presence of CB1 protein has not yet been rigorously demonstrated in these cells. In the present study, we tested a polyclonal antibody that recognizes a large segment of the C terminus of the CB1 protein (described by Fukudome et al., 2004). First, we confirmed the specificity of the antibody in CB1 knock-out mice (Fig. 6, compare A, B). Beside some scattered glial processes, we did not observe any labeling corresponding to neurons in these mice. In contrast, in wild-type mice, the CB1 antibody revealed a hippocampal immunostaining that was much denser and patterned than seen previously with other antibodies (Fig. 6A,C–E). The distribution of immunostaining followed the layered structure of the hippocampus, showing the highest density in the inner molecular layer of the dentate gyrus, followed by the stratum radiatum of the CA1 and CA3 subfields. Besides this strong labeling outlining the hippocampal layers, the well described interneuron cell bodies along with their typical dense axon arbor carrying large, strongly labeled boutons also appeared in the immunostaining. Notably, the stratum lucidum of CA3 was indeed “lucid,” i.e., the neuropil showed no labeling, as expected from the lack of CB1 mRNA in dentate granule cells, and contained only the interneuron axons (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Localization of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor protein in the hippocampus delineates the topographical arrangement of glutamatergic pathways. A, Light micrograph illustrating CB1 immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of wild type (WT) mouse. By using a novel guinea pig antibody, the immunostaining highlights the different layers of the hippocampus according to the spatial arrangements of the excitatory pathways. B, In contrast, immunostaining in the hippocampus of a CB1 knock-out mouse shows no immunopositive profiles, demonstrating antibody specificity. C, At higher magnification, the CB1-immunoreactive GABAergic interneurons and their characteristic basket-like axon arbor is visible in the stratum pyramidale (s.p.) of the CA3 subfield. Moreover, the dense neuropil labeling throughout the strata radiatum (s.r.) and oriens (s.o.), in which local axon collaterals of the CA3 pyramidal neurons arborize, appears in strong contrast with the immunonegative stratum lucidum (s.l.), the termination zone of the axon terminals of the granule cells. D, In the CA1 subfield, the same but somewhat fainter neuropil labeling is observed, besides the interneuronal profiles. E, In the dentate gyrus (DG), the most striking labeling appears in the inner third of stratum moleculare (s.m.), which is the termination zone of the axons of the mossy cells, the glutamatergic interneurons of the dentate gyrus. Modest staining is found in the outer parts of stratum moleculare, whereas only interneuronal somata and axons are visible in the stratum granulosum (s.g.). Scale bars: A, B, 300 μm; C, 50 μm; D, E, 75 μm.

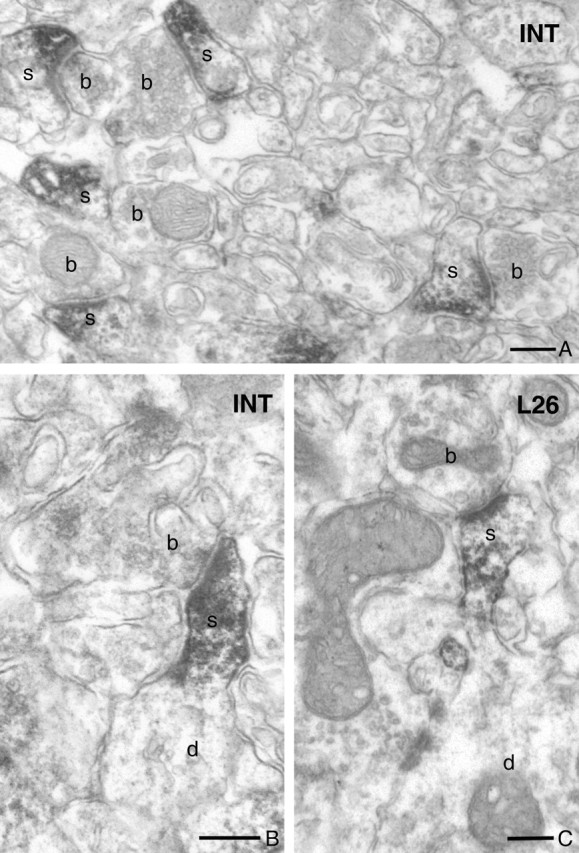

To determine the nature of the novel neuropil-like labeling pattern, we performed an electron microscopic analysis in both wild-type and CB1 knock-out animals (Fig. 7). CB1 immunostaining was absent in sections from knock-out animals, and the labeling was restricted to two types of axon terminals in wild-type animals. Besides the GABAergic interneurons, which form symmetrical synapses, numerous axon terminals forming excitatory-type asymmetrical synapses were also immunopositive for CB1 receptors. We found that >80% of axon terminals with asymmetrical synapses were unequivocally positive for CB1 in the inner third of stratum moleculare (Fig. 7A), the most strongly labeled layer at the light microscopic level. In other layers of the hippocampus, we typically obtained a ratio of ∼30–50%. High-resolution silver-enhanced immunogold staining further confirmed the validity of the findings, because immunogold particles representing the precise subcellular localization of CB1 were always attached to the intracellular side of the plasma membrane as predicted by the spatial localization of the epitope (Fig. 7B–D).

Figure 7.

CB1 cannabinoid receptors are localized presynaptically on both glutamatergic and GABAergic axon terminals in the hippocampus. A, The electron micrograph demonstrates the striking accumulation of strong CB1 immunoreactivity within axon terminals in the inner third of the stratum moleculare of the dentate gyrus. Two types of boutons are labeled for CB1. Excitatory axon terminals, which form asymmetrical synapses depicted by arrowheads, and inhibitory axon terminals, which form symmetrical synapses indicated by single arrow. GABAergic axon terminals, which lack presynaptic CB1 receptors, are labeled by double arrows. B–D, Immunogold labeling reveals a characteristic presynaptic localization of CB1, which is attached to the intracellular surface of the plasma membrane in both types of axon terminals (b1–b3) in accordance with the epitope localization. The electron micrographs are taken from stratum moleculare (B1, B2 are serial sections), from stratum oriens of the CA3 subfield (C) and from stratum radiatum of the CA1 subfield (D). Large arrows point to immunogold particles representing the localization of CB1, whereas arrowheads point to excitatory synapses and small arrows point to inhibitory synapses. Scale bars: A, 0.5 μm; B–D, 0.2 μm.

To determine whether the presence of CB1 receptors on glutamatergic axon terminals was species or strain dependent, we repeated the experiments in both C57BL/6 and CD1 mice and found no differences. Furthermore, immunostaining for CB1 using the novel antibody visualizes glutamatergic axon terminals in both rat and human hippocampus (Katona et al., unpublished observations).

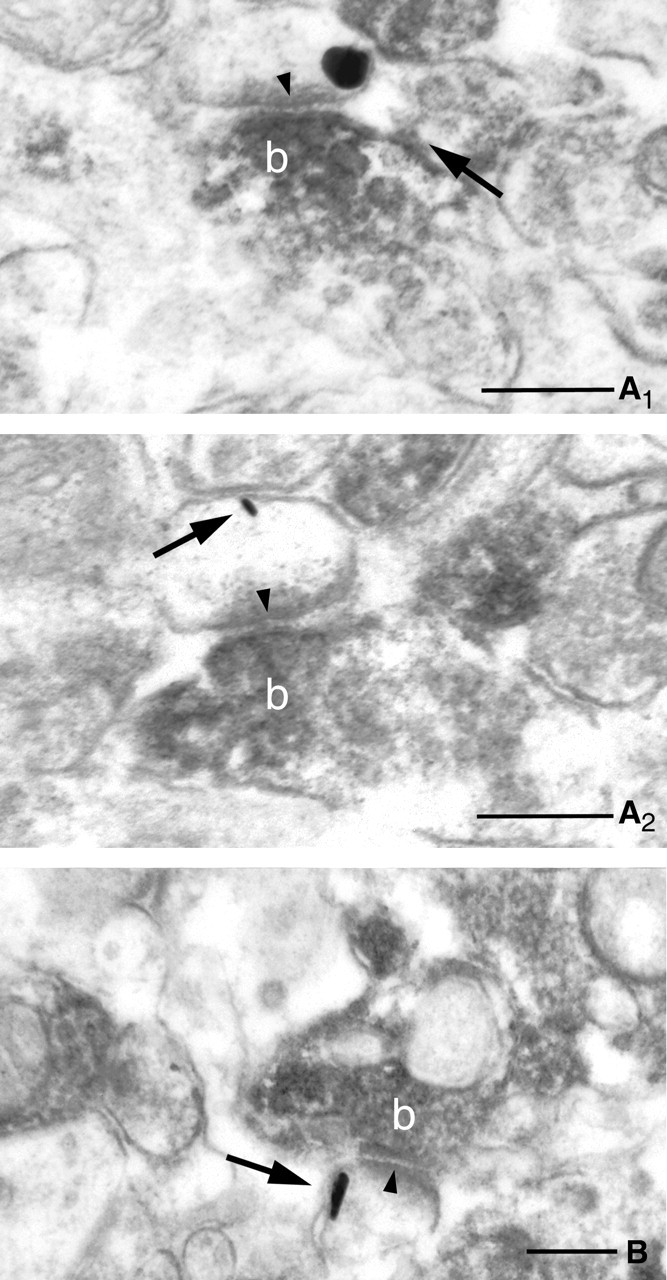

DGL-α and CB1 receptors are colocalized on the postsynaptic and presynaptic sides of glutamatergic contacts, respectively

Because all three antibodies used in this study resulted in incomplete labeling of the corresponding neuronal profiles, the colocalization of these postsynaptic and presynaptic proteins within the same spine population cannot be inferred from single immunostaining experiments. Exploiting the fact that the primary antibodies against DGL-α or CB1 were raised in rabbit and guinea pig, respectively, we performed double immunostainings in which DGL-α was visualized using the immunogold procedure and CB1 was visualized using the immunoperoxidase (DAB) technique. Extensive electron microscopic analysis confirmed in most layers of all three subfields of the hippocampus that DGL-α is localized on postsynaptic spine heads receiving an asymmetrical synapse from CB1-bearing axon terminals (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Complementary localization of postsynaptic DGL-α and presynaptic CB1 receptors at glutamatergic synapses. A–C, High-power electron micrographs confirm that DGL-α, the synthesizing enzyme for the endocannabinoid 2-AG and CB1 cannabinoid receptor, and its molecular target are localized in the same glutamatergic synapses. Combination of preembedding immunogold labeling for DGL-α and immunoperoxidase staining for CB1 reveals the postsynaptic position of this enzyme (indicated by arrows) and presynaptic localization of the receptor (the dense precipitate within the axon terminals labeled by b). The strong asymmetrical postsynaptic density (arrowheads) demonstrates that these are excitatory, glutamatergic synapses. Electron micrographs are taken from stratum radiatum of CA3 (A1, A2 are serial sections) and from stratum radiatum of CA1 (B). Scale bars: A, B, 0.2 μm.

Discussion

According to the current dogma, endocannabinoids are derived from postsynaptic elements; hence, they may be retrograde modulators in a number of synaptic plasticity paradigms. Conversely, the precise source of endocannabinoids and the enzymes responsible for their on-demand synthesis at different types of synapses remain unknown. In the present study, we found the following: (1) DGL-α, a primary synthesizing enzyme for the endocannabinoid 2-AG, is highly expressed by the glutamatergic principal cell populations of the hippocampus; (2) DGL-α is concentrated on the head of dendritic spines, the specialized postsynaptic microdomains receiving glutamatergic synaptic input; (3) in relation to glutamate release sites, DGL-α is strikingly concentrated in the perisynaptic annulus around the synaptic specialization with a decrement along the extrasynaptic membrane surface, but it is almost entirely excluded from the synaptic junction itself; and (4) on the opposite side of the glutamatergic synapse, CB1 cannabinoid receptors are localized presynaptically on glutamatergic axon terminals on most excitatory pathways in the hippocampus.

Postsynaptic DGL-α at glutamatergic synapses

The most important finding of the present study is the provocative gradient of DGL-α within the head of dendritic spines of pyramidal neurons and granule cells. Three experimental findings support the validity of this immunocytochemical result. First, in situ hybridization using two independent riboprobes revealed very high expression levels of DGL-α in the three major cell types bearing dendritic spines, namely in the granule cells of the dentate gyrus and in pyramidal cells of the CA3 and CA1 subfields. Second, the strong DGL-α immunoreactivity in spine heads was observed using two distinct antibodies raised against two independent epitopes on DGL-α. Third, high-resolution immunogold labeling by both antibodies resulted in a labeling pattern corresponding to the predicted topology of DGL-α, i.e., immunogold particles were always attached to the intracellular surface of the spine plasma membrane.

Dendritic spines are highly versatile structures. It is widely accepted that their activity-dependent reorganization reflects experience-dependent changes in neuronal function (Segal, 2005). The head of the spine is usually innervated by a single excitatory axon terminal, which forms a characteristic asymmetrical synapse with a pronounced postsynaptic density. The narrow spine neck serves as a barrier for most signaling pathways to ensure synapse-specific plasticity mechanisms. From this aspect, it is interesting to note that current models identify endocannabinoids as the most probable candidates to serve as the retrograde signal in homosynaptic long-term plasticity at glutamatergic synapses (Gerdeman et al., 2002; Robbe et al., 2002; Sjostrom et al., 2003). The finding that the endocannabinoid synthesizing enzyme DGL-α is localized on the head of the spine is in complete agreement with this proposed model. Furthermore, several findings point to 2-AG as the main endocannabinoid involved in hippocampal synaptic plasticity at both the glutamatergic (Stella et al., 1997; Straiker and Mackie, 2005) and GABAergic (Chevaleyre and Castillo, 2003; Kim and Alger, 2004; Makara et al., 2005) synapses. Because DGL-α may be a key enzyme for 2-AG synthesis in the postnatal brain (Bisogno et al., 2003), the demonstration of its presence postsynaptically at glutamatergic synapses provides anatomical support for the conclusion of previous physiological experiments obtained by pharmacological tools.

Remarkably, we did not find DGL-α labeling at symmetrical synapses formed by GABAergic boutons despite focused searching. This may simply reflect a level of DGL-α that is below the threshold of detection in our experiments. Conversely, two laboratories recently reported that the exclusively postsynaptic depolarization-dependent form of endocannabinoid-mediated synaptic depression at GABAergic synapses [“conventional” depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition (DSI)] is not blocked by DGL inhibitors (Chevaleyre and Castillo, 2003; Edwards et al., 2006). In contrast, inhibitors of the 2-AG degrading enzyme, MGL, prolong DSI, suggesting 2-AG involvement in this form of synaptic plasticity (Makara et al., 2005). It will be important to determine whether alternative biochemical pathways for 2-AG synthesis, e.g., involving phospholipase A1 and lyso-phospholipase C (PLC), operate at GABAergic synapses. Similarly, the lack of DGL-α in GABAergic interneurons may reflect an expression level below our detection threshold. However, it has been reported that retrograde endocannabinoid signaling is absent from these cells (Hoffman et al., 2003). Together, these findings provide clear evidence that distinct endocannabinoid signaling pathways exist in parallel in the brain, and, to understand their physiological significance (e.g., how they are recruited and at which types of synapses they operate), the precise molecular and spatial properties of each of their components must be carefully determined.

Perisynaptic DGL-α pool underlies a functional link to mGluR5 receptors

Ample evidence is available that the endocannabinoid system is also involved in heterosynaptic plasticity (for review, see Chevaleyre et al., 2006). The best example is heterosynaptic long-term depression of inhibition (I-LTD) in CA1 pyramidal cells. This phenomenon is expressed presynaptically on GABAergic axon terminals, but induced postsynaptically by stimulation of the glutamatergic Schaffer collaterals, and is dependent on the activation of postsynaptic type I mGluRs (Chevaleyre et al., 2003; Chevaleyre and Castillo, 2004). CA1 pyramidal cells express mainly the mGluR5 subtype of type I mGluRs, whereas mGluR1 is found in selected types of interneurons (Baude et al., 1993; Lujan et al., 1996). A precise analysis of the subcellular distribution of mGluR5 on CA1 pyramidal cells revealed that these receptors are segregated into a perisynaptic pool around the postsynaptic specialization on the head of dendritic spines (Lujan et al., 1996, 1997). Using the same criteria for DGL-α on a large population of CA1 pyramidal cell dendritic spines, we found a similar perisynaptic accumulation within 60 nm of the edge of the synaptic junction as reported for mGluR5 (Lujan et al., 1997, their Fig. 5B,B′), along with a similar gradient of decreasing extrasynaptic distribution. Importantly, mGluR5 activates PLC-β, which produces certain DAG species, including those with arachidonic acid at the sn-2 position that serve as precursors for 2-AG synthesis. Indeed, pharmacological activation of mGluR5 induces a considerable amount of 2-AG release in striatal and hippocampal cultures, which can be blocked by PLC-β and DGL inhibitors (Jung et al., 2005). The inhibition of I-LTD by DGL inhibitors (Chevaleyre et al., 2003; Edwards et al., 2006) and the perisynaptic colocalization of mGluR5 with DGL-α suggest that mGluR5 and DGL-α cooperate to produce 2-AG at glutamatergic synapses during heterosynaptic long-term depression. It is noteworthy that type I mGluR activation also contributes to other, short-term forms of endocannabinoid-dependent synaptic plasticity at hippocampal GABAergic synapses (Varma et al., 2001; Ohno-Shosaku et al., 2002a), which are also dependent on DGL activity (Edwards et al., 2006). In contrast, mGluRs are not involved in DSI, because DSI cannot be blocked by DGL inhibitors (Chevaleyre and Castillo, 2003; Edwards et al., 2006) and persists in PLC-β1 knock-out animals (Hashimotodani et al., 2005). This striking heterogeneity in the biochemical signaling pathways and the spatial segregation of mGluR5 and DGL-α suggest that 2-AG-mediated endocannabinoid signaling may differ between distinct types of synapses and contribute differently to homosynaptic and heterosynaptic plasticity.

Presynaptic CB1 cannabinoid receptors at glutamatergic synapses

The molecular identification of presynaptic cannabinoid receptors at glutamatergic synapses in the hippocampus has been a controversial issue since the first description of cannabinoid effects on excitatory neurotransmission (Shen et al., 1996). Although the specificity of weak CB1 mRNA signal in hippocampal pyramidal cells was confirmed by using an elegant mouse model in which CB1 is deleted selectively in principal cells (Marsicano et al., 2003), its functional significance has been hampered by the fact that the CB1 deletion occurs prenatally, thereby developmental consequences could not be ruled out. Second, our own anatomical studies, in accordance with data from other laboratories, revealed that GABAergic axon terminals in the hippocampus express strikingly high levels of CB1 receptors (Katona et al., 1999; Tsou et al., 1999; Egertova and Elphick, 2000; Fukudome et al., 2004), in contrast to glutamatergic boutons that were found to be CB1 negative. Here we provide direct anatomical evidence using a highly sensitive antibody that CB1 receptors do occur presynaptically on glutamatergic terminals. Furthermore, very recently, two independent papers appeared demonstrating that presynaptic CB1 receptors on glutamatergic axon terminals are functionally coupled to inhibition of glutamate release in the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus of adult mice (Kawamura et al., 2006; Takahashi and Castillo, 2006), thereby emphasizing the functional significance of the present anatomical findings and those of Kawamura et al. (2006). The previous negative findings may have been caused by the fact that the expression level of CB1 is much lower in principal cells than in interneurons and the antibodies used in previous studies were not sensitive enough to visualize lesser amounts of CB1 on glutamatergic boutons. In addition, the CB1 receptor-interacting protein, which is thought to be expressed selectively by principal neurons and binds to the last nine amino acids of CB1, may have also obscured labeling by some C-terminal antibodies of principal cells through epitope masking (Niehaus et al., 2004).

In conclusion, the striking spatial organization of the endocannabinoid system involving a postsynaptic synthetic enzyme (DGL-α) and a presynaptic receptor (CB1) provides direct anatomical support for the view that 2-AG is a retrograde signaling molecule at glutamatergic synapses in the CNS.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (T.F.F.), Országos Tudományos Kutatási Alapprogramok Grants T046820 (T.F.F.) and F046407 (I.K.), Nemzeti Kutatási és Fejlesztési Pályázatok Grant 1A/002/2004 (T.F.F.), National Institutes of Health Grants DA00286 and DA11322 (K.M.), NS30549 (T.F.F.), and DA12447 and DA12413 (D.P.), and European Union Contract LSHM-CT-2004-005166 (T.F.F.). I.K. is a grantee of the János Bolyai scholarship. We are very grateful to Prof. Masahiko Watanabe for the generous gift of the CB1 antibody raised in guinea pig and to Dr. Sayaka Sugiyama for her help with in situ hybridization. We also thank Katalin Lengyel, Katalin Iványi, Emőke Simon, and Győző Goda for excellent technical assistance, Drs. Judit K. Makara and Norbert Hájos for comments on this manuscript and for help in statistical analysis, and Barna Dudok for his help with the preparation of the figures.

References

- Alger BE (2002). Retrograde signaling in the regulation of synaptic transmission: focus on endocannabinoids. Prog Neurobiol 68:247–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baude A, Nusser Z, Roberts JD, Mulvihill E, McIlhinney RA, Somogyi P (1993). The metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR1 alpha) is concentrated at perisynaptic membrane of neuronal subpopulations as detected by immunogold reaction. Neuron 11:771–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg M, Pacher P, Batkai S, Osei-Hyiaman D, Offertaler L, Mo FM, Liu J, Kunos G (2005). Evidence for novel cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol Ther 106:133–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltramo M, Stella N, Calignano A, Lin SY, Makriyannis A, Piomelli D (1997). Functional role of high-affinity anandamide transport, as revealed by selective inhibition. Science 277:1094–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogno T, Howell F, Williams G, Minassi A, Cascio MG, Ligresti A, Matias I, Schiano-Moriello A, Paul P, Williams EJ, Gangadharan U, Hobbs C, Di Marzo V, Doherty P (2003). Cloning of the first sn1-DAG lipases points to the spatial and temporal regulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. J Cell Biol 163:463–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevaleyre V, Castillo PE (2003). Heterosynaptic LTD of hippocampal GABAergic synapses: a novel role of endocannabinoids in regulating excitability. Neuron 38:461–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevaleyre V, Castillo PE (2004). Endocannabinoid-mediated metaplasticity in the hippocampus. Neuron 43:871–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevaleyre V, Takahashi KA, Castillo PE (2006). Endocannabinoid-mediated synaptic plasticity in the CNS. Annu Rev Neurosci 29:37–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cravatt BF, Giang DK, Mayfield SP, Boger DL, Lerner RA, Gilula NB (1996). Molecular characterization of an enzyme that degrades neuromodulatory fatty-acid amides. Nature 384:83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, Pertwee RG, Stevenson LA, Griffin G, Gibson D, Mandelbaum A, Etinger A, Mechoulam R (1992). Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science 258:1946–1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diana MA, Marty A (2004). Endocannabinoid-mediated short-term synaptic plasticity: depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition (DSI) and depolarization-induced suppression of excitation (DSE). Br J Pharmacol 142:9–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh TP, Carpenter D, Leslie FM, Freund TF, Katona I, Sensi SL, Kathuria S, Piomelli D (2002). Brain monoglyceride lipase participating in endocannabinoid inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:10819–10824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards DA, Kim J, Alger BE (2006). Multiple mechanisms of endocannabinoid response initiation in hippocampus. J Neurophysiol 95:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egertova M, Elphick MR (2000). Localisation of cannabinoid receptors in the rat brain using antibodies to the intracellular C-terminal tail of CB. J Comp Neurol 422:159–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fegley D, Kathuria S, Mercier R, Li C, Goutopoulos A, Makriyannis A, Piomelli D (2004). Anandamide transport is independent of fatty-acid amide hydrolase activity and is blocked by the hydrolysis-resistant inhibitor AM1172. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:8756–8761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF, Katona I, Piomelli D (2003). Role of endogenous cannabinoids in synaptic signaling. Physiol Rev 83:1017–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukudome Y, Ohno-Shosaku T, Matsui M, Omori Y, Fukaya M, Tsubokawa H, Taketo MM, Watanabe M, Manabe T, Kano M (2004). Two distinct classes of muscarinic action on hippocampal inhibitory synapses: M2-mediated direct suppression and M1/M3-mediated indirect suppression through endocannabinoid signalling. Eur J Neurosci 19:2682–2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdeman GL, Lovinger DM (2003). Emerging roles for endocannabinoids in long-term synaptic plasticity. Br J Pharmacol 140:781–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdeman GL, Ronesi J, Lovinger DM (2002). Postsynaptic endocannabinoid release is critical to long-term depression in the striatum. Nat Neurosci 5:446–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hájos N, Katona I, Naiem SS, MacKie K, Ledent C, Mody I, Freund TF (2000). Cannabinoids inhibit hippocampal GABAergic transmission and network oscillations. Eur J Neurosci 12:3239–3249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hájos N, Ledent C, Freund TF (2001). Novel cannabinoid-sensitive receptor mediates inhibition of glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Neuroscience 106:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimotodani Y, Ohno-Shosaku T, Tsubokawa H, Ogata H, Emoto K, Maejima T, Araishi K, Shin HS, Kano M (2005). Phospholipase Cbeta serves as a coincidence detector through its Ca2+ dependency for triggering retrograde endocannabinoid signal. Neuron 45:257–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillard CJ, Edgemond WS, Jarrahian A, Campbell WB (1997). Accumulation of N-arachidonoylethanolamine (anandamide) into cerebellar granule cells occurs via facilitated diffusion. J Neurochem 69:631–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman AF, Riegel AC, Lupica CR (2003). Functional localization of cannabinoid receptors and endogenous cannabinoid production in distinct neuron populations of the hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci 18:524–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman AF, Macgill AM, Smith D, Oz M, Lupica CR (2005). Species and strain differences in the expression of a novel glutamate-modulating cannabinoid receptor in the rodent hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci 22:2387–2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung KM, Mangieri R, Stapleton C, Kim J, Fegley D, Wallace M, Mackie K, Piomelli D (2005). Stimulation of endocannabinoid formation in brain slice cultures through activation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. Mol Pharmacol 68:1196–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona I, Sperlagh B, Sik A, Kafalvi A, Vizi ES, Mackie K, Freund TF (1999). Presynaptically located CB1 cannabinoid receptors regulate GABA release from axon terminals of specific hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci 19:4544–4558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura Y, Fukaya M, Maejima T, Yoshida T, Miura E, Watanabe M, Ohno-Shosaku T, Kano M (2006). The CB1 cannabinoid receptor is the major cannabinoid receptor at excitatory presynaptic sites in the hippocampus and cerebellum. J Neurosci 26:2991–3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Alger BE (2004). Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 potentiates retrograde endocannabinoid effects in hippocampus. Nat Neurosci 7:697–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledent C, Valverde O, Cossu G, Petitet F, Aubert JF, Beslot F, Bohme GA, Imperato A, Pedrazzini T, Roques BP, Vassart G, Fratta W, Parmentier M (1999). Unresponsiveness to cannabinoids and reduced addictive effects of opiates in CB1 receptor knockout mice. Science 283:401–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lujan R, Nusser Z, Roberts JD, Shigemoto R, Somogyi P (1996). Perisynaptic location of metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR1 and mGluR5 on dendrites and dendritic spines in the rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci 8:1488–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lujan R, Roberts JD, Shigemoto R, Ohishi H, Somogyi P (1997). Differential plasma membrane distribution of metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR1 alpha, mGluR2 and mGluR5, relative to neurotransmitter release sites. J Chem Neuroanat 13:219–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makara JK, Mor M, Fegley D, Szabo SI, Kathuria S, Astarita G, Duranti A, Tontini A, Tarzia G, Rivara S, Freund TF, Piomelli D (2005). Selective inhibition of 2-AG hydrolysis enhances endocannabinoid signaling in hippocampus. Nat Neurosci 8:1139–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsicano G, Goodenough S, Monory K, Hermann H, Eder M, Cannich A, Azad SC, Cascio MG, Gutierrez SO, van der Stelt M, Lopez-Rodriguez ML, Casanova E, Schutz G, Zieglgansberger W, Di Marzo V, Behl C, Lutz B (2003). CB1 cannabinoid receptors and on-demand defense against excitotoxicity. Science 302:84–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI (1990). Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature 346:561–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechoulam R, Ben-Shabat S, Hanus L, Ligumsky M, Kaminski NE, Schatz AR, Gopher A, Almog S, Martin BR, Compton DR, Pertwee RG, Griffin G, Bayewitch M, Barg J, Vogel Z (1995). Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem Pharmacol 50:83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M (1993). Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature 365:61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehaus JL, Wallis KT, Elphick MR, Lewis DL (2004). CRIP1B, a novel CB1 cannabinoid receptor interacting protein, interacts with CB1 at the distal C-terminal tail. Soc Neurosci Abstr 30:623.19. [Google Scholar]

- Ohno-Shosaku T, Shosaku J, Tsubokawa H, Kano M (2002a). Cooperative endocannabinoid production by neuronal depolarization and group I metabotropic glutamate receptor activation. Eur J Neurosci 15:953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno-Shosaku T, Tsubokawa H, Mizushima I, Yoneda N, Zimmer A, Kano M (2002b). Presynaptic cannabinoid sensitivity is a major determinant of depolarization-induced retrograde suppression at hippocampal synapses. J Neurosci 22:3864–3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto Y, Morishita J, Tsuboi K, Tonai T, Ueda N (2004). Molecular characterization of a phospholipase D generating anandamide and its congeners. J Biol Chem 279:5298–5305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piomelli D (2003). The molecular logic of endocannabinoid signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci 4:873–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbe D, Kopf M, Remaury A, Bockaert J, Manzoni OJ (2002). Endogenous cannabinoids mediate long-term synaptic depression in the nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:8384–8388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen S, Skaletsky H (2000). Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol 132:365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal M (2005). Dendritic spines and long-term plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci 6:277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen M, Piser TM, Seybold VS, Thayer SA (1996). Cannabinoid receptor agonists inhibit glutamatergic synaptic transmission in rat hippocampal cultures. J Neurosci 16:4322–4334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjostrom PJ, Turrigiano GG, Nelson SB (2003). Neocortical LTD via coincident activation of presynaptic NMDA and cannabinoid receptors. Neuron 39:641–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella N, Schweitzer P, Piomelli D (1997). A second endogenous cannabinoid that modulates long-term potentiation. Nature 388:773–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straiker A, Mackie K (2005). Depolarization-induced suppression of excitation in murine autaptic hippocampal neurones. J Physiol (Lond) 569:501–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura T, Kondo S, Sukagawa A, Nakane S, Shinoda A, Itoh K, Yamashita A, Waku K (1995). 2-Arachidonoylglycerol: a possible endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand in brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 215:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi KA, Castillo PE (2006). The CB1 cannabinoid receptor mediates glutamatergic synaptic suppression in the hippocampus. Neuroscience in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tsou K, Mackie K, Sanudo-Pena MC, Walker JM (1999). Cannabinoid CB1 receptors are localized primarily on cholecystokinin-containing GABAergic interneurons in the rat hippocampal formation. Neuroscience 93:969–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma N, Carlson GC, Ledent C, Alger BE (2001). Metabotropic glutamate receptors drive the endocannabinoid system in hippocampus. J Neurosci 21:RC188(1–5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, Nicoll RA (2002). Endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. Science 296:678–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]