Abstract

Some species of enterococci and streptococci are difficult to differentiate by phenotypic traits. The feasibility of using an oligonucleotide array for identification of 11 viridans group streptococci was previously established. The aim of this study was to expand the array to identify species of Abiotrophia (1 species), Enterococcus (18 species), Granulicatella (3 species), and Streptococcus (31 species and 6 subspecies). The method consisted of PCR amplification of the ribosomal DNA intergenic spacer (ITS) regions, followed by hybridization of the digoxigenin-labeled PCR products to a panel of oligonucleotide probes (16- to 30-mers) immobilized on a nylon membrane. Probes could be divided into three categories: species specific, group specific, and supplemental probes. All probes were designed either from the ITS regions or from the 3′ ends of the 16S rRNA genes. A collection of 312 target strains (162 reference strains and 150 clinical isolates) and 73 nontarget strains was identified by the array. Most clinical isolates were isolated from blood cultures or deep abscesses, and only those strains having excellent species identification with the Rapid ID 32 STREP system (bioMérieux Vitek, Taipei, Taiwan) were used for array testing. The test sensitivity and specificity of the array were 100% (312/312) and 98.6% (72/73), respectively. The whole procedure of array hybridization took about 8 h, starting from isolated colonies, and the hybridization patterns could be read by the naked eye. The oligonucleotide array is accurate for identification of the above microorganisms and could be used as a reliable alternative to phenotypic identification methods.

Enterococci, nutritionally variant streptococci, most of which have been allocated to the genera Abiotrophia and Granulicatella, and streptococci are gram-positive and catalase-negative bacteria. Although many species of the above genera are commensals of the human body, some of them cause local or systemic infections, including subacute endocarditis, bacteremia, meningitis, pneumonia, soft-tissue infections, and eye infections (15, 22, 41, 49). Sherman (46) proposed a scheme for dividing the streptococci into four categories: the pyogenic division, the viridans division, the lactic division, and the enterococci. No single system of phenotypic identification suffices for the differentiation of this heterogeneous group of organisms. Instead, classification depends on a combination of features, including patterns of hemolysis on blood agar plates, antigenic composition, growth characteristics, and biochemical reactions (15, 41). Accurate identification of these bacteria would be useful for understanding the pathogenesis of infections and the epidemiology of the increasing antibiotic resistance among some of these microorganisms (50).

In clinical laboratories, phenotypic test kits, such as the Rapid ID 32 STREP system (bioMérieux Vitek, Taipei, Taiwan), the API 20 STREP system (bioMérieux Vitek), or the Vitek GPI card (bioMérieux Vitek), are commonly used for identification of enterococci, streptococci, and related bacteria (16, 23, 28). The inherent problem of the culture-based identification of these microorganisms is the large number of species relative to the limited number of biochemical traits, the poor reproducibility of some tests (4, 41), the variability of some traits within species (6, 24, 41), and the lack of sufficient phenotypic data on more recently described species. The last problem applies to species such as Streptococcus australis, Streptococcus cristatus, Streptococcus infantarius subspecies infantarius, Streptococcus infantis, Streptococcus gallolyticus, and Streptococcus lutetiensis (38, 44).

A variety of molecular methods have been developed for identification of strains of enterococci, viridans group streptococci, and streptococci to the species level. The targets used for molecular diagnosis include genes encoding rRNA (6, 10, 26, 27), the beta subunit of RNA polymerase (rpoB) (14), the d-alanine:d-alanine ligase (18), the RNA subunit of RNase P (rnpB) (25), the elongation factor (tuf) (36), the manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase (sodA) (37, 38), the heat shock proteins (groESL) (51), and the tRNA gene intergenic spacer (2, 3, 12). Recently, nonhemolytic streptococci were successfully identified by phylogenetic sequence analysis of four housekeeping genes (ddl, gdh, rpoB, and sodA) (24). Correct identification of catalase-negative gram-positive cocci is to some extent achievable by sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene (6, 27). However, there are two problems with this approach. First, the method does not allow differentiation of Streptococcus mitis, Streptococcus oralis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae because of significant sequence conservation of the 16S rRNA genes in this group of bacteria (6, 24). Second, many sequences in the public databases are mislabeled, either because of incorrect identification on the source strain or because of nonrecorded revised classification of the strain subsequent to deposition of the sequence (24).

The 16S-23S rRNA gene intergenic spacer (ITS) has been suggested as a good candidate for bacterial identification and strain typing (8, 19, 21, 40). The ITS region is found to have a high degree of sequence and length variation at both the genus and species levels (21, 30, 55). Recently, DNA array technology was found to be a useful tool to identify (or detect) a wide variety of microorganisms (7, 17, 29, 34, 43, 53, 54). In our previous study, the feasibility of using an oligonucleotide array to identify 11 species of viridans group streptococci was established (9). This study aimed to expand the results of the array technique to cover a more comprehensive spectrum including 53 species and 6 subspecies of Abiotrophia, Enterococcus, Granulicatella, and Streptococcus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A collection of 312 target strains (162 reference strains and 150 clinical isolates) was analyzed (Table 1). Reference strains were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, Va.), the Bioresources Collection and Research Center (BCRC, Hsinchu, Taiwan), and the Culture Collection of the University of Göteborg (CCUG, Göteborg, Sweden). Clinical isolates were obtained from the National Taiwan University Hospital (Taipei, Taiwan), the National Cheng Kung University Medical Center (Tainan, Taiwan), and the Ghent University Hospital (Ghent, Belgium). Most clinical isolates were isolated from blood cultures or deep abscesses and identified to the species level with the Rapid ID 32 STREP system. To avoid ambiguous identities of clinical isolates, only those strains having excellent species identification according to the criteria of the Rapid ID 32 STREP system were used for array testing. In addition, species names of clinical isolates of viridans group streptococci were verified by ITS sequence analysis as previously described (8). In addition, a total of 73 nontarget strains (belonging to 51 species other than the species covered by the DNA array) were used for a specificity test of the array (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). All strains were cultured on sheep blood agar, incubated at 35°C for 24 to 48 h, and then used for DNA extraction. Strains of Abiotrophia and Granulicatella were cultured on chocolate agar.

TABLE 1.

Reference strains and clinical isolates used in this study

| Species | Reference strain(s)a | No. of clinical isolates | Total no. of strains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus | |||

| E. avium | BCRC 10801T, CCUG 34661, 44888 | 4 | 7 |

| E. casseliflavus | ATCC 12755, 12817, CCUG 18657T | 7 | 10 |

| E. cecorum | ATCC 43198T, BAA150, CCUG 38939 | 0 | 3 |

| E. columbae | CCUG 27894T | 0 | 1 |

| E. dispar | CCUG 33309T, 37857 | 0 | 2 |

| E. durans | ATCC 19432T, CCUG 46232, 37858, 44816, LMG 16886 | 1 | 6 |

| E. faecalis | ATCC 19433T, 27332 | 13 | 15 |

| E. faecium | ATCC 19434T, CCUG 37851, 46070 | 11 | 14 |

| E. flavescens | CCUG 30567T, 30568, 30569 | 0 | 3 |

| E. gallinarum | ATCC 49573T, CCUG 29831, 34517 | 6 | 9 |

| E. gilvus | CCUG 45553T, LMG 13600 | 0 | 2 |

| E. hirae | ATCC 8043T, BCRC 11547, 12496 | 3 | 6 |

| E. mundtii | ATCC 43186T, LMG 12308 | 0 | 2 |

| E. pallens | CCUG 45554T | 0 | 1 |

| E. pseudoavium | CCUG 33310T, 44888 | 0 | 2 |

| E. raffinosus | CCUG 29292T, 37864, 37865 | 0 | 3 |

| E. saccharolyticus | CCUG 33311T, NCIMB 702609 | 0 | 2 |

| E. villorum | CCUG 45025T, LMG 19177 | 0 | 2 |

| Streptococcus | |||

| S. agalactiae | ATCC 13813T | 13 | 14 |

| S. alactolyticus | BCRC 14738T, CCUG 41502, 41503 | 0 | 3 |

| S. anginosus | ATCC 33397T, 700231 | 5 | 7 |

| S. australis | CCUG 45919T, 45974, 45975 | 0 | 3 |

| S. bovis | ATCC 33317T, CCUG 4214 | 0 | 2 |

| S. canis | BCRC 14753T, CCUG 27660 | 0 | 2 |

| S. constellatus | ATCC 27513T, 27823 | 5 | 7 |

| S. cristatus | CCUG 33481T, 30424, 35233 | 0 | 3 |

| S. downei | BCRC 14752T | 0 | 1 |

| S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis | ATCC 9542, 35666, CCUG 27483, 27479 | 7 | 11 |

| S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus | BCRC 14756T, 15414, CCUG 43890 | 0 | 3 |

| S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus | ATCC 43143T, CCUG 35224, 46101, 46667 | 5b | 9 |

| S. gallolyticus subsp. macedonicus | CCUG 39970T, 33369, 43003 | 0 | 3 |

| S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus | ATCC 43144T, CCUG 19454, 35885, 46034, 46150 | 7b | 12 |

| S. gordonii | ATCC 35105T, 49818 | 1 | 3 |

| S. infantarius subsp. infantarius | ATCC BAA102T, CCUG 43820, 43821, 44960, 47548 | 0 | 5 |

| S. infantis | CCUG 39817T, 39818, 39821 | 0 | 3 |

| S. iniae | BCRC 14744T, CCUG 27623 | 0 | 2 |

| S. intermedius | ATCC 27335T | 3 | 4 |

| S. lutetiensis | CCUG 43822T, 38926, 43823 | 0 | 3 |

| S. mitis | ATCC 49456T, 15910, 15914 | 5 | 8 |

| S. mutans | BCRC 15255, 15256, CCUG 35254 | 5 | 8 |

| S. oralis | ATCC 35037T, 9811, 15914, 55229, 700233, 700234 | 6 | 12 |

| S. parasanguinis | ATCC 15912T, 15909 | 4 | 6 |

| S. parauberis | LMG 12174 | 0 | 1 |

| S. pneumoniae | ATCC 33400T, 6301, 27336, 49619 | 9 | 13 |

| S. porcinus | BCRC 14751T, CCUG 7982, 41363 | 0 | 3 |

| S. pyogenes | ATCC 14289T, 12344 | 8 | 10 |

| S. ratti | CCUG 27641T, 27642, BCRC 15255, 15256 | 0 | 4 |

| S. salivarius | ATCC 7073T, 13419, 25975, CCUG 32749B | 6 | 10 |

| S. sanguinis | ATCC 10556T, 49295, 49296 | 3 | 6 |

| S. sobrinus | BCRC 14757T, CCUG 21019, 35254 | 0 | 3 |

| S. suis | BCRC 14757T, CCUG 42755, 42756 | 0 | 3 |

| S. thermophilus | BCRC 13869T, ATCC 15910, CCUG 35458 | 0 | 3 |

| S. uberis | ATCC 19436T, 13386, 700407 | 1 | 4 |

| S. urinalis | CCUG 41590T, 41825 | 0 | 2 |

| S. vestibularis | CCUG 24893T, 32749 | 0 | 2 |

| Nutritionally variant streptococci | |||

| Abiotrophia defectiva | ATCC 49176T, CCUG 27805 | 5 | 7 |

| Granulicatella | |||

| G. adiacens | ATCC 49175T, CCUG 27811, 44406, 44407, 44408 | 7 | 12 |

| G. balaenopterae | CCUG 37380T | 0 | 1 |

| G. elegans | CCUG 38949T, 13462, 26024, 27554 | 0 | 4 |

| Total | 150 | 312 |

ATCC: American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.; BCRC, Bioresources Collection and Research Center, Taiwan; CCUG, Culture Collection of the University of Göteborg, Sweden; LMG, Laboratorium voor Microbiologie, Belgium; NCIMB, The National Collection of Industrial, Marine and Food Bacteria, United Kingdom. A total of 162 reference strains were used.

Three biotypes (I, II.1, and II.2) are recognized by the Rapid ID 32 STREP system. S. bovis biotypes I and II.2 were renamed S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus and S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus, respectively (44).

DNA preparation.

The boiling method was used to extract DNA from bacteria (31). Briefly, one to several colonies of pure cultures were suspended in 50 μl of sterilized water, heated at 100°C for 15 min in a heating block, and centrifuged in a microcentrofuge (6,000 × g; 10 min). The supernatant containing bacterial DNA was stored at −20°C for further use.

Database of oligonucleotide probes.

A total of 88 oligonucleotide probes (16- to 30-mers) (Table 2) were used to construct an oligonucleotide database to identify the bacteria listed in Table 1. Most probes were designed from the ITS regions, except for five that were based on the sequences of the 3′ ends of 16S rRNA genes. Reference sequences extracted from GenBank (Table 1) were confirmed by at least one sequence of another reference strain of the same species in the database. If an ITS sequence was determined in this study and used for probe design, the sequence was also confirmed by using the ITS sequence of a second reference strain of the same species, except for a few species that had only one strain in our collection (Table 1).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide probes used in this study

| Microorganism | Probe

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Length (bp) | Tm (°C) | Locationb | GenBank accession no. | |

| Enterococcus | ||||||

| E. avium | Eav | TACAGAAACAATTTTAAACAA(T) | 21 | 40.3 | 140-160 | AY351315 |

| E. casseliflavus/E. flavescens | Ecasc | GAGTTGAAATGTTAAAAGAG(T) | 20 | 38.4 | 128-147 | DQ204549 |

| E. cecorum | Ecec1 | TGCTTTATTATTTAAAAGATCTGA(T) | 24 | 45.7 | 246-269 | DQ217843 |

| Ecec2 | ATATTGAAAAGTAATACAAAAAAAC(T) | 25 | 44.2 | 182-206 | DQ217843 | |

| E. columbae | Ecol1 | GAAGAGAAACATCAATTAATAAACCG(T) | 26 | 52.1 | 92-117 | DQ204548 |

| Ecol2 | ACAGGWTTTGCTTTTGTTCA(T) | 20 | 47.4 | 22-41 | DQ204548 | |

| E. dispar | Edi1 | CTGGATACTTGAAGAAAAGAATCAAA(T) | 26 | 52.5 | 91-116 | DQ204544 |

| Edi2 | TCTTGAGTAAGCTTCTATC(T) | 19 | 35.3 | 172-190 | DQ204544 | |

| Edi3 | GAAGAACTGCTCAAAACCAGACC(T) | 23 | 53.8 | 195-217 | DQ204544 | |

| E. durans | Edu1 | TGACATTAGAGGATACTCTCAAGAGAAT(T) | 28 | 52.6 | 93-120 | X87178z |

| Edu2 | TAATTGAAGAGTCAGGTTATGACTTTGACA(T) | 30 | 57.1 | 68-97 | X87178 | |

| E. faecium | Efm1 | TTTTATGAGACGATCGAT(T) | 18 | 39.3 | 204-221 | AY351321 |

| Efm2 | TCTTGATCTAACTTCTAT(T) | 18 | 28.6 | 287-304 | AY351321 | |

| E. faecalis | Efs1 | TATTTATTGATTAACCTTCT(T) | 20 | 35.8 | 164-183 | AY351322 |

| Efs2 | AAGAAGTGATCAAGACCCA(T) | 19 | 43.6 | 192-210 | AY351322 | |

| E. gallinarum | Egal | GAGTGGACAAGTTAAAGA(T) | 18 | 35.5 | 125-142 | DQ204550 |

| E. gilvus | Egi1 | GAAACAAAATGTTAAACAAAC(T) | 21 | 41.6 | 112-132 | DQ204551 |

| E. hirae | Ehi1 | TTTGTTTTTCACTTTG(T) | 18 | 37.1 | 28-45 | X87184 |

| Ehi2 | CTCAAAGATATATTTTTG(T) | 20 | 36.0 | 65-84 | X87184 | |

| E. mundtii | Emut | (T)TACACACGTTTGTCGATACTT | 21 | 44.9 | 21-41 | DQ204542 |

| E. pallens | Epal1 | (T)GTGACAGCAATGTTGCCTAGCG | 22 | 57.2 | 16-37 | DQ204541 |

| Epal2 | TACAGAAAATAAACAAACAAAC(T) | 22 | 41.8 | 122-143 | DQ204541 | |

| Epal3 | GAAGAGAAGATCAAGAACCAACC(T) | 23 | 50.6 | 218-240 | DQ204541 | |

| E. pseudoavium | Eps1 | TCGCTCATGAAAGTTAGTAAG(T) | 21 | 44.5 | 199-209 | DQ204540 |

| Eps2 | ATTACTAACGGAAATGATCG(T) | 20 | 48.2 | 182-201 | DQ204540 | |

| E. raffinosus | Era | CAGAAACACATTTTTTTAAA(T) | 20 | 40.3 | 112-131 | DQ204533 |

| E. saccharolyticus | Esac | TTCTTGATAAAACTTCT(T) | 17 | 29.5 | 168-184 | DQ204538 |

| E. villorums | Evi1 | GGATAGAAATTCATTTTTCTACGCA(T) | 25 | 53.1 | 92-116 | DQ204537 |

| Evi2 | TTTAGTTGGTTTTGATATGAGAC(T) | 23 | 45.4 | 117-139 | DQ204537 | |

| Streptococcus | ||||||

| S. agalactiae | Saga | (T)GGAAACCTGCCATTTGCGTCTT | 22 | 59.0 | 9-30 | AY347539 |

| S. anginosus | Sang1d | AGAATCCTACTGAACTTAATAAAGAAGTGA(T) | 30 | 53.0 | 137-166 | AY347541 |

| Sang2 | AACCGTCTCTTACTATCCTAA(T) | 21 | 42.2 | 269-289 | AY347541 | |

| S. australis | Sau1 | (T)ATCACCAAGGATGAACATT | 19 | 43.3 | 137-155 | DQ204552 |

| S. alactolyticus | Sala | (T)GGTCAATAAGACCAAA | 16 | 33.1 | 251-266 | AY353082 |

| Salbec | ACGTTTGGAGTATTGTT(T) | 17 | 35.7 | 19-35 | AY347544 | |

| S. bovis | Salbec | ACGTTTGGAGTATTGTT(T) | 17 | 35.7 | 19-35 | AY347544 |

| Sbecc | CCACGATTCAAGAAATTGAATTGT(T) | 24 | 54.1 | 183-206 | AY347544 | |

| S. canis | Scan | (T)CTGTAAGTATTAAAGAGTTTTTTCTA | 26 | 44.1 | 237-262 | DQ204523 |

| S. constellatus | Scon1d | ATCTAGGATGCAAAGAAATGAGA(T) | 23 | 49.5 | 132-154 | AY347545 |

| Scon2 | TTGTTCAACTAGATAAGATAGGATA(T) | 25 | 44.5 | 158-182 | AY347545 | |

| S. cristatus | Scri | GGATAGTGGAAACTATTCTAAAC(T) | 23 | 43.8 | 258-280 | DQ204522 |

| S. downei | Sdow1 | TTCTTAGGGCAGTCATCTAAATCACAA(T) | 27 | 56.6 | 73-99 | DQ204520 |

| Sdow2 | TTAGCCAAAGTGGTTAATAGAAGTAC(T) | 26 | 50.1 | 120-145 | DQ204520 | |

| S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis | Sdyeq | (T)TGTGAATAATCAAGAGTT | 18 | 32.9 | 239-256 | DQ204519 |

| S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus | Sequi | AACGCTGTGATAACGAGTTTAAA(T) | 23 | 50.7 | 573-595 | DQ204517 |

| S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus | Sgalgmc | (T)ACGTTTGGGAAGTCTTG | 17 | 41.9 | 20-36 | DQ204512 |

| S16STe,f | AGGTGGGATAGATGATT(T) | 17 | 36.9 | 17-33 | DQ204553 | |

| S. gallolyticus subsp. macedonicus | Sgalgmc | (T)ACGTTTGGGAAGTCTTG | 17 | 41.9 | 20-36 | DQ204512 |

| S16SCe,f | AGGTGGGATAGATGATT(T) | 17 | 36.9 | 16-32 | DQ204555 | |

| S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus | Sgalp | (T)AAGATTCAAAGTGATTGTC | 19 | 37.8 | 138-156 | DQ204506 |

| S. gordonii | Sgor1d | GAAGTTCCAAACTAGTCCATTG(T) | 22 | 47.6 | 136-157 | AY353081 |

| Sgor2 | AATGCACGATGGAGTC(T) | 16 | 39.5 | 15-30 | AY353081 | |

| S. infantarius subsp. infantarius | Sinfcolc | ACGTTTGGGTATTGTTTA(T)AT | 18 | 39.9 | 19-36 | DQ204502 |

| Sinfsalc | ATGAGTTAGGTCGAAAGGCC(T) | 20 | 50.0 | 246-265 | DQ204499 | |

| S. infantis | Smgc | TAAGGAACTGCACATTGGTC(T) | 20 | 47.4 | 8-27 | AY347551 |

| Sinf1e,f | AGGTAACCATTTGGAGCCAG(T) | 20 | 50.8 | 1419-1438 | AY485603 | |

| S. iniae | Sini1 | TCCATAGACAAGGAAGTCTCTAAA(T) | 25 | 49.7 | 369-393 | DQ204504 |

| Sini2 | ACAAGGAAGTCTCTAAAATACGTGAAG(T) | 28 | 50.4 | 295-322 | DQ204504 | |

| S. intermedius | Sinte1d | AGGATATGGAATTCACCTTTAGTTG(T) | 25 | 52.0 | 132-156 | AY347549 |

| Sinte2d | TTTAGTTGATGATATCCTAAAGTAG(T) | 25 | 44.4 | 149-173 | AY347549 | |

| S. mitis | Smgc | TAAGGAACTGCACATTGGTC(T) | 20 | 47.4 | 8-27 | AY347551 |

| Smgmo1e,f | AGGTAACCTTTTAGGAGCCA(T) | 19 | 47.7 | 1436-1454 | AF003930 | |

| Smgmp1e | TAGTATTAATAAGAGTTTAT(T) | 20 | 27.9 | 208-227 | AY347550 | |

| S. lutetiensis | Sbecc | CCACGATTCAAGAAATTGAATTGT(T) | 24 | 54.1 | 183-206 | AY347544 |

| Sinfcolc | ACGTTTGGGTATTGTTTA(T) | 18 | 39.9 | 19-36 | DQ204502 | |

| S. mutans | Smut1 | (T)GGATAGGTTAAGTATCCTAGAGATGG | 26 | 50.5 | 269-294 | AE014133 |

| Smut2 | GAATAGCTAGTAAAAGCCCTATAGC(T) | 25 | 49.4 | 308-332 | AE014133 | |

| S. oralis | Smgc | TAAGGAACTGCACATTGGTC(T) | 20 | 47.4 | 8-27 | AY347551 |

| Smgmo1e,f | AGGTAACCTTTTAGGAGCCA(T) | 19 | 47.7 | 1436-1454 | AF003930 | |

| Smgor1e | TAGTATTAAAAGAGTTTAT(T) | 19 | 27.7 | 207-225 | AY347551 | |

| S. parasanguinis | Sparasan | TTTAGGTCGCAAGACCA(T) | 17 | 43.8 | 226-242 | AY351320 |

| S. parauberis | Sparaub | GGTCTTATTAAAGTAATGAG(T) | 20 | 35.4 | 48-67 | AF255656 |

| S. pneumoniae | Smgc | TAAGGAACTGCACATTGGTC(T) | 20 | 47.4 | 8-27 | AY347551 |

| Smgmp1e | TAGTATTAATAAGAGTTTAT(T) | 20 | 27.9 | 208-227 | AY347550 | |

| Smgp1e,f | AGGTAACCGTAAGGAGCCA(T) | 20 | 48.9 | 1436-1455 | AF003930 | |

| S. porcinus | Spor | GTCTTATTTAAGTTATGAGAAC(T) | 22 | 37.3 | 48-69 | DQ204498 |

| S. pyogenes | Spyo | (T)CTAAACTTAATACAAGTGAAGT | 22 | 37.9 | 141-162 | AY347560 |

| S. ratti | Srat1 | ATACAAAGAGATGTTCGGAAGAGGACA(T) | 27 | 57.6 | 266-292 | DQ204497 |

| Srat2 | CGGAAGAGGACAATTTTGTATTCTAGT(T) | 27 | 54.8 | 314-340 | DQ204497 | |

| S. salivarius | Sinfsa1c | ATGAGTTAGGTCGAAAGGCC(T) | 20 | 50.0 | 246-265 | DQ204499 |

| Ssalc | (T)GGAATGTACTTGAGTTTCTTATT | 23 | 44.0 | 13-35 | AY347561 | |

| S16STe,f | AGGTGGGATAGATGATT(T) | 17 | 36.9 | 17-33 | DQ204553 | |

| S. sanguinis | Ssand | GACACACGGAATGCACTTGA(T) | 20 | 51.5 | 17-36 | AY347565 |

| S. sobrinus | Ssob | (T)TAGGACGGCCATCTT | 16 | 39.5 | 76-91 | DQ204560 |

| S. suis | Ssui | (T)GGAAACCTGTACGTCAGTCTT | 21 | 47.6 | 11-31 | DQ204558 |

| S. thermophilus | Sinfsa1c | ATGAGTTAGGTCGAAAGGCC(T) | 20 | 50.0 | 246-265 | DQ204499 |

| Ssalc | (T)GGAATGTACTTGAGTTTCTTATT | 23 | 44.0 | 13-35 | AY347561 | |

| S16SCe,f | AGGTGGGACAGATGATT(T) | 17 | 40.2 | 16-32 | DQ204555 | |

| Stve | GTCGAAAGGCCAAAATA(T) | 17 | 42.9 | 256-272 | U32965 | |

| S. uberis | Sube1d | GGATACAGTTCAACTGAACTTAATA(T) | 25 | 46.7 | 150-174 | AY347538 |

| Sube2d | CATTGTATCTTAGTATAGTCCATTG(T) | 25 | 45.0 | 186-210 | AY347538 | |

| S. urinalis | Sur1 | (T)ATGGAAACGATTGGTCGTCT | 20 | 50.9 | 9-28 | DQ204552 |

| Sur2 | TCTAGGATAGTCCATTGACAATTG(T) | 24 | 49.8 | 139-162 | DQ204552 | |

| S. vestibularis | Sinfsa1c | ATGAGTTAGGTCGAAAGGCC(T) | 20 | 50.0 | 246-265 | DQ204499 |

| Ssalc | (T)GGAATGTACTTGAGTTTCTTATT | 23 | 44.0 | 13-35 | AY347561 | |

| S16STe,f | AGGTGGGATAGATGATT(T) | 17 | 36.9 | 17-33 | DQ204553 | |

| Stve | GTCGAAAGGCCAAAATA(T) | 17 | 42.9 | 256-272 | U32965 | |

| Nutritionally variant streptococci | ||||||

| Abiotrophia defectiva | Ade | AAATAGCGCGAAAGTATCATGCATCAA(T) | 27 | 60 | 198-224 | AY351327 |

| Granulicatella | ||||||

| G. adiacens | Gad | TATCACAACAAATAACCAATTAA(T) | 23 | 44.6 | 219-241 | AY353083 |

| G. balaenopterae | Gbal1 | ATAACGGAACCTACCAAGTTCACTTCT(T) | 27 | 56.2 | 11-37 | DQ204534 |

| Gbal2 | TGAGAGATTAATTCTCTCTAGACTTTGATC(T) | 30 | 53.2 | 49-78 | DQ204534 | |

| Gbal3 | GCAAACGCGAATCATATTGAGACTTAA(T) | 27 | 58.8 | 177-203 | DQ204534 | |

| G. elegans | Gele1 | GAGGTTAACTCTCAACTCGACCTTTGAAAA | 30 | 60.5 | 76-105 | DQ204535 |

| Gele2 | TTTAACAAGAAGCAACGCGACCATA | 25 | 58.9 | 176-200 | DQ204535 | |

| Positive control | PCg | (T)GTCGTAACAAGGTAGCCGTA | 20 | 47.3 | 1474-1493 | AB023575 |

(T), additional bases of thymine were added to the 5′ or 3′ end of the probe. If Tm was ≤37°C, 15 thymine bases were added; if Tm was ≤45°C, 10 thymine bases were added; and if Tm was ≥45°C, 5 thymine bases were added to the probe.

The location of the probe is indicated by the nucleotide number of the ITS sequence, except where otherwise indicated.

Group-specifics probes.

Probe sequences already published (9).

Supplemental probes.

Probes designed from the 16S rRNA genes.

The positive control probe was designed from a conserved region at the 3′ end of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene.

Alignments of the ITS sequences of different species were performed by using the PrettyBox algorithm of the Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group package (version 10.3; Accelrys Inc., San Diego, Calif.), and areas displaying sequence divergence among species were used for probe synthesis. The designed probes were checked for internal repeats, self-biding, secondary structure, and GC content by using the software Vector NTI (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, Calif.) and screened against the databases of the National Center for Biotechnology Information for homology with other bacterial sequences using BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool). Fifteen, ten, or five additional bases of thymine were added to the 3′ (or 5′) ends of probes that had Tm values less than 37°C, 45°C, or 50°C, respectively (7) (Table 2). Some probes used for identification of viridans group streptococci were reported previously (9); however, many probes were newly designed or modified to identify several additional species in this group and to meet the change of hybridization stringency used in this study (Table 2).

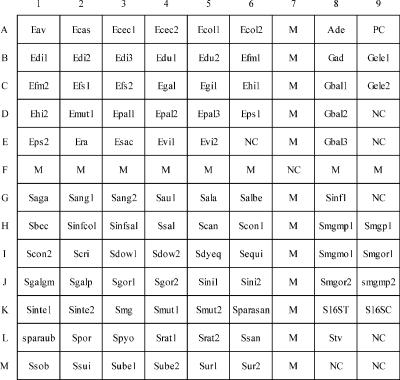

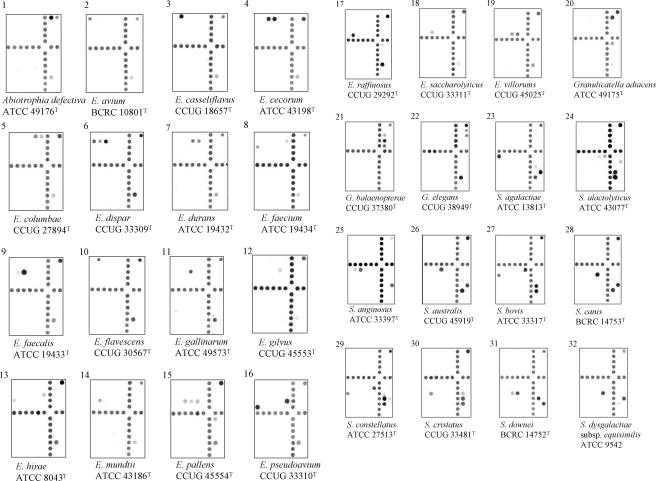

One probe or multiple probes were designed to identify a single species, depending on the availability of divergent sequences in the ITS regions (Table 2). The 88 probes could be divided into 3 categories: species specific, group specific (i.e., a probe shared by several species), and supplemental probe (i.e., a probe used to differentiate between genetically related streptococci). Supplemental probes were either designed from the ITS regions or from the 3′ ends of the 16S rRNA genes. A probe based on a conserved sequence (5′-GTCGTAACAAGGTAGCCGTA-3′) at the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA gene (GenBank accession no. AB023575) was used as a positive control probe. In addition, the digoxigenin-labeled reverse primer 6R (5′-dig-GGGTTYCCCCRTTCRGAAAT-3′ ; Y = C or T, and R = A or G), used to amplify the ITS region, was spotted on the array and used as a position marker after hybridization (Fig. 1 and 2).

FIG. 1.

Layout of oligonucleotide probes on the array (0.9 by 1.1 cm). The probe “PC” (A9) (a positive control) was designed from a conserved region at the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA gene. Probes coded “NC” were negative controls (tracking dye only). Probes coded “M” were digoxigenin-labeled primer 6R and were used as position markers. Probes in the upper left, upper right, and lower left corners were used to identify species of nutritionally variant streptococci, enterococci, and streptococci, respectively. Probes in the lower right corner were supplemental probes. The corresponding sequences of all probes are listed in Table 2.

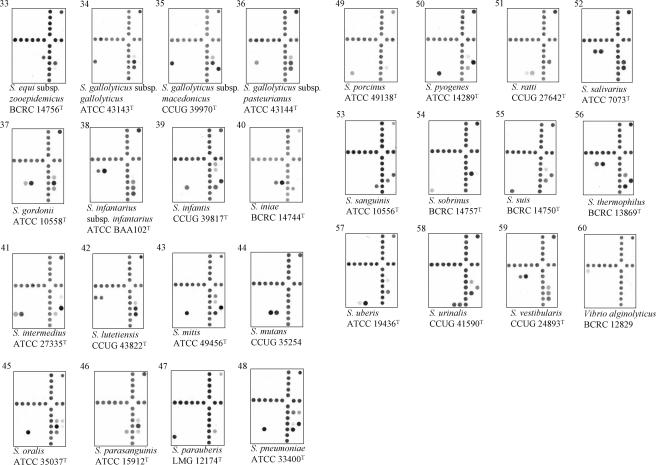

FIG. 2.

Hybridization results for species of enterococci (18 species), streptococci (31 species and 6 subspecies), and nutritionally variant streptococci (4 species). All strains, except two, were type strains and were alphabetically arranged according to their species names. The corresponding probes hybridized on the arrays are indicated in Fig. 1, and the corresponding sequences of the hybridized probes are shown in Table 2. The hybridized probe on the uppermost right corner on each array was the positive control. Hybridization signals produced by supplemental probes (located at the lower right corner) were used to differentiate genetically related species of streptococci and had no use in identification of enterococci and nutritionally variant streptococci.

Fabrication of oligonucleotide arrays.

The array (0.9 by 1.1 cm) contained 117 dots (9 × 13 dots), including 88 dots for species (or subspecies) identification, 1 dot for a positive control (probe code PC), 8 dots for negative controls (probe code NC, tracking dye only), and 20 dots (probe code M) for position markers (Fig. 1). The oligonucleotide probes were diluted 1:1 (final concentration, 10 μM) with a tracking dye solution, drawn into wells of 96-well microtiter plates, and spotted onto positively charged nylon membranes (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) as described previously (9). The arrays were fabricated with an automatic arrayer (SR-A300; Ezspot, Taipei, Taiwan) by using a solid pin (diameter, 400 μm). Probes on the array were divided by position markers into four areas. Probes in the upper left, upper right, and lower left corner were used for identification of species of nutritionally variant streptococci, enterococci, and streptococci, respectively. The lower right corner contained supplemental probes that helped group-specific probes to differentiate some genetically related streptococci (Fig. 1).

Amplification of the ITS regions for hybridization.

The bacterium-specific universal primers 13 BF (5′-GTGAATACGTTCCCGGGCCT-3′) and 6R (5′dig-GGGTTYCCCCRTTCRGAAAT3′) (Y = C or T, and R = A or G) (39) were used to amplify a DNA fragment that encompassed a small portion of the 16S rRNA gene, the ITS, and a small portion of the 23S rRNA gene. The reverse primer 6R was labeled with a digoxigenin molecule at its 5′ end. PCR was carried out as described previously (9), except that digoxigenin-11-dUTP was not included in the PCR mixture.

Hybridization procedures.

Unless otherwise indicated, the hybridization procedures were carried out at room temperature in an oven with a shaking speed of 60 rpm. All reagents except buffers were included in the DIG nucleic acid detection kit (Roche). Each array was prehybridized for 2 h with 1 ml of hybridization solution (5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 1% [wt/vol] blocking reagent, 0.1% N-laurylsarcosine, 0.02% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) in an individual well of a 12-well cell culture plate. The digoxigenin-labeled PCR product amplified from an isolate was heated on a 100°C heating block for 5 min and immediately cooled in an ice bath. Ten microliters of the denatured PCR product of the test organism was diluted with 0.5 ml of hybridization solution and added to each well. Hybridization was carried out at 45°C for 90 min. The array was then given three washes (5 min each) in 1 ml of washing buffer (2× SSC, 0.1% SDS) and one wash (1 min) in 1 ml of a second washing buffer (0.5× SSC, 0.1% SDS). The array was then blocked with 1% blocking solution supplied in the DIG nucleic acid detection kit (Roche), incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated sheep antidigoxigenin antibodies and then with the substrates of alkaline phosphatase as described previously (9). The hybridized chip was air-dried, and the image of the hybridization pattern was processed by a high-resolution scanner (Powerlook 3000; Umax, Taipei, Taiwan). The hybridized spot (diameter, 400 μm), displaying a blue color on a white nylon membrane, could be easily recognized by the naked eye.

Identification of strains by array hybridization.

A strain was identified as one of the species (or subspecies) listed in Table 1 when the probe (or all probes) specified for that species was hybridized (Table 2). Unless otherwise specified, hybridization signals produced by supplemental probes located in the lower right corner of the array were ignored. Some species were identified by their unique hybridization patterns, produced by group-specific or group-specific and supplemental probes, as indicated in Table 2. Supplemental probes were used to differentiate several genetically related streptococci; they had no use for identification of enterococci and nutritionally variant streptococci.

Discrepant analysis.

When a strain produced discrepant identification by the array, the near-complete-length 16S rRNA gene of the strain was amplified by PCR and sequenced for species clarification. To amplify the near-complete-length 16S rRNA gene by PCR, the primer pair of 8FPL (5′-GTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492RPL (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) was used (39). PCR products were purified by a PCR-M Clean Up kit (Viogene, Taipei, Taiwan) and sequenced in both directions by using the above two primers and an additional primer, 1055r (5′-CACGAGCTGACGACAGCCAT-3′) with the BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Taipei, Taiwan) and the ABI 377 sequencing system (Applied Biosystems). The determined sequences were compared to known sequences of 16S rRNA genes in the databases of the National Center for Biotechnology Information using the BLASTN algorithm. The following criteria were used for identification of a strain to the genus or species level by 16S rRNA gene sequencing: (i) when the comparison of the determined sequence with a best-scoring reference sequence of a classified species yielded an identity of ≥99%, the unknown isolate was assigned to that species; and (ii) when the identity was <99% and ≥95%, the unknown isolate was assigned to the corresponding genus (6).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences of accession numbers with a prefix of “DQ” in Table 2 were determined in this study and have been submitted to GenBank.

RESULTS

Construction of oligonucleotide probe database.

A total of 88 probes (Table 2) were used to construct an oligonucleotide database, which was then used for fabrication of the array shown in Fig. 1. Among the 88 probes, 70 were species specific, 8 were group specific, and 10 were supplemental probes. A group-specific probe (such as the probes Ecas and Salbe) could hybridize with the PCR products of two or more species due to high sequence similarities among these species (Table 2). Supplemental probes were designed from the ITS or the 16S rRNA gene regions that were coamplified by PCR during ITS amplification and were used to differentiate genetically related species of streptococci.

An individual species was identified by one to four probes, depending on the availability of divergent sequences in the ITS region. For example, Enterococcus avium was identified by a single probe (Eav), while a strain was identified as Enterococcus dispar if all three probes (Edi1, Edi2, and Edi3) were simultaneously hybridized (Table 2). Some species were identified by a combination of group-specific probes. For example, Streptococcus bovis was identified by its hybridization to two group-specific probes, Salbe and Sbec (Table 2; Fig. 2). Although Streptococcus alactolyticus also hybridized to the probe Salbe and S. lutetiensis hybridized to the probe Sbec, neither species could simultaneously hybridize with both probes. Furthermore, some species were identified by their unique patterns of hybridization to group-specific and supplemental probes. For example, both S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus and S. gallolyticus subsp. macedonicus hybridized with the group-specific probe Sgalgm and were differentiated by hybridization to two supplemental probes, S16SC and S16ST. S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus produced positive hybridization with the probe S16ST, whereas S. gallolyticus subsp. macedonicus was positive with the probe S16SC (Table 2; Fig. 2). Another example was S. mitis and S. oralis; both species hybridized to the group-specific probe Smg and the supplemental probe Smgmo1. The two species were distinguished by hybridization of S. mitis to an additional supplemental probe, Smgmp1, and S. oralis to another supplemental probe, Smgor1 (Table 2; Fig. 2). Species that required group-specific and supplemental probes for identification are indicated in Table 2.

Identification of reference strains by the oligonucleotide array.

Of 162 target reference strains tested, 154 hybridized to their respective oligonucleotide probes and were correctly identified. The hybridization patterns of 53 species and 6 subspecies, a majority of them being type strains, on the arrays are alphabetically shown in Fig. 2. Reference strains of the different taxa in the S. bovis complex, i.e., S. bovis, S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus, S. gallolyticus subsp. macedonicus, and S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus, were successfully differentiated by the array. Species that have high sequence similarities in their 16S rRNA genes were also accurately identified by the present method. These species were S. mitis and S. pneumoniae, Streptococcus gordonii and S. mitis, Enterococcus durans and Enterococcus faecium, and Enterococcus gallinarum and Enterococcus casseliflavus (27, 35).

Eight reference strains (4.9%), including one enterococcal and seven streptococcal species, produced discrepant identification by the array. Determination of the 16S rRNA gene sequences of these strains showed that six of the eight strains had been given wrong species names (Table 3). Enterococcus pseudoavium CCUG 44888 was identified as E. avium by array hybridization. A BLAST search revealed that the 16S rRNA gene sequence of the strain CCUG 44888 had identities of 99.1 and 98.8% with GenBank reference sequences of E. avium and E. pseudoavium, respectively (Table 3). Therefore, E. pseudoavium CCUG 44888 should be a strain of E. avium, as identified by the array and confirmed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Similarly, Streptococcus mutans BCRC 15255, S. mutans BCRC 15256, Streptococcus sobrinus CCUG 35254, Streptococcus uberis ATCC 13386, and Streptococcus vestibularis CCUG 32749 were found to be misidentifications of Streptococcus ratti, S. ratti, Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus parauberis, and Streptococcus salivarius, respectively, as revealed by array hybridization and further confirmed by their 16S rRNA gene sequences (Table 3). S. cristatus CCUG 35233 and S. mitis ATCC 15914 were identified only to the genus level (Streptococcus) by sequencing of the 16S rRNA genes (Table 3), since the identities between the query sequences and the best-scoring reference sequences in the public databases were only 98%. However, a BLAST search of the ITS sequences of S. cristatus CCUG 35233 and S. mitis ATCC 15914 against GenBank revealed that the both best-scoring sequences were from S. oralis, with sequence identities of 99.6% and 99.1%, respectively. To further clarify the identities of strains CCUG 35233 and ATCC 15914, the manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase genes (sodA) of both strains were amplified (38) and sequenced. A BLAST search of the sodA sequences of strains CCUG 35233 and ATCC 15914 revealed that the best-scoring reference sequences were S. oralis (GenBank accession no. Z99195; sequence identity, 96%) and S. oralis (GenBank accession AB200066; sequence identity, 96%), respectively. Since the hybridization results for strains CCUG 35233 and ATCC 15914 were supported by sequence analysis of the ITS region and sodA gene, the two strains were considered to be correctly identified as S. oralis by the array. Since all eight discordant reference strains were proved to be correctly identified by array hybridization, the test sensitivity of the array for reference strains was 100% (162/162).

TABLE 3.

Strains that produced discrepant identification by array hybridization and results of discrepant analysis

| Strain | Species name received | Species identification by:

|

Result of discrepant analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Array hybridization | 16S rRNA gene sequence (%)a | |||

| CCUG 44888 | E. pseudoavium | E. avium | E. avium (99.1), E. pseudoavium (98.8) | E. avium |

| CCUG 35233 | S. cristatus | S. oralis | S. oralis (98), S. mitis (98) | S. oralisb |

| ATCC 15914 | S. mitis | S. oralis | S. oralis (98), S. mitis (98), S. pneumoniae (98) | S. oralisb |

| BCRC 15255 | S. mutans | S. ratti | S. ratti (99), S. mutansc(92) | S. ratti |

| BCRC 15256 | S. mutans | S. ratti | S. ratti (99), S. mutans (92) | S. ratti |

| CCUG 35254 | S. sobrinus | S. mutans | S. mutans (99), S. sobrinus (90) | S. mutans |

| ATCC 13386 | S. uberis | S. parauberis | S. parauberis (99), S. uberis (92) | S. parauberis |

| CCUG 32749 | S. vestibularis | S. salivarius | S. salivarius (99.7), S. vestibularis (99.1) | S. salivarius |

| 2510c | E. avium | E. raffinosus | E. raffinosus (100), E. avium (99) | E. raffinosus |

| 790c | E. durans | E. hirae | E. hirae (99), E. durans (98) | E. hirae |

Values in parentheses are percentages of 16S rRNA gene sequence identities of the test strains with sequences in GenBank.

CCUG 35233 and ATCC 15914 were found to be S. oralis by sequence analysis of the ITS region (8) and the manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase gene (sodA) (38).

Clinical isolates.

Identification of clinical isolates by the oligonucleotide array.

Of 150 target clinical isolates tested, E. avium 2510 and E. durans 790 yielded discrepant identifications by array hybridization (Table 3). E. avium 2510 and E. durans 790 were identified as, respectively, Enterococcus raffinosus and Enterococcus hirae by the array, and this identification was confirmed by sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA genes. Since these two discordant isolates were proved to be correctly identified by hybridization, the test sensitivity of the array for clinical isolates was 100% (150/150). If reference strains and clinical isolates were considered together, an overall sensitivity of 100% (312/312) was obtained by the present method.

Hybridization of nontarget strains to the oligonucleotide array.

Of 73 nontarget strains (51 species) tested by the array (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), one strain (Vibrio alginolyticus BCRC 12829) hybridized to the probe Saga and was misidentified as Streptococcus agalactiae (Fig. 2). The remaining 72 strains did not produce any hybridization signals with probes on the array, except for the positive control probe. Therefore, the test specificity of the array was 98.6% (72/73).

DISCUSSION

In this study, an oligonucleotide array was developed to identify 53 species and six subspecies of the genera Abiotrophia, Enterococcus, Granulicatella, and Streptococcus. A sensitivity of 100% (312/312) and a specificity of 98.6% (72/73) were obtained by the array. The present method used a standardized protocol encompassing DNA extraction, PCR amplification of the ITS regions, and hybridization of the PCR products to the array. The hybridized spot (400 μm in diameter), displaying a blue color on a white nylon membrane, could be easily recognized by the naked eye. The whole procedure can be finished within approximately 8 h, starting from isolated colonies. The present method might be useful for conditions that necessitate identification of enterococci, streptococci, and related bacteria to the species (and subspecies) level.

In this study, an individual species was identified by either one or multiple probes, depending on the availability of divergent sequences in the ITS region. The advantage of using multiple probes is the increase in specificity, since the chance for a cross-reacting strain to hybridize to all probes designed for a species is very low. However, the use of multiple probes to identify a species may potentially decrease sensitivity, due to the possibility of mutations that occur at the regions used for probe design. The successful design of different probes, including group-specific and supplemental probes, was based on the known sequences in regions of the ITS and the 3′ ends of 16S rRNA genes. Multiple sequence alignment (interspecies and intraspecies) plays an essential role in finding out the regions that could be used for probe design.

Routine procedures based on phenotypic tests do not allow unequivocal identification of some streptococci. Hoshino et al. (24) examined a collection of 115 strains of nonhemolytic streptococci isolated from bacteremic patients and 33 reference strains by using 2 commercial kits (rapid ID 32 STREP and STREPTOGRAM [Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan]). The correct identification rates for strains by both commercial kits were below 50% but varied significantly between species. The most significant problems were observed with S. mitis and S. oralis and 11 Streptococcus species described since 1991. They concluded that phenotypic characterization is of limited value for identification of many species of nonhemolytic streptococci and is not a valid approach at the present time. Recently, Bosshard et al. (6) tested 171 strains of aerobic catalase-negative gram-positive cocci with the API 20 STREP system and found that less than 60% of isolates could be identified to the species or genus level. To solve the problems of phenotypic identification, the feasibility of using an oligonucleotide array for species identification was investigated here and favorable results were obtained. The array technology has been used to identify a spectrum of microorganisms, including Mycobacterium (17, 34, 43), bacteria in positive blood cultures (7), bacteria from cervical swab specimens (32), Campylobacter (53), Listeria (54), and food-borne bacterial pathogens (29).

Clinical isolates used in this study were identified by the Rapid ID 32 STREP system. To avoid as much as possible discrepant identification results, thus avoiding sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA gene as much as possible, only those strains having excellent species identification (i.e., percent identification of ≥99.9%) according to the criteria of the ID 32 STREP system were used for array testing. Strains with good identification (percent identification of ≥90%) or acceptable identification (percent identification of ≥ 80%) were not included in this study, since Bosshard et al. (6) observed that such identifications were unreliable. In addition, clinical isolates of viridans group streptococcus were verified by ITS sequence analysis before hybridization (8). The primary screening and verification of clinical isolates may partially explain why only 2 out of 150 isolates yielded discrepant identifications by array hybridization. This screening largely limited the numbers of strains and species that could be tested in this study. Moreover, the database of the Rapid ID 32 STREP system does not include many recently described species listed in Table 1, such as S. australis, S. cristatus, S. infantarius subspecies infantarius, S. infantis, S. gallolyticus, and others. Therefore, clinical isolates of these recently described species were not available for array testing. The accuracy of the array for identification of species listed in Table 1 could be regarded as being mainly based on testing of reference strains.

Pairwise comparison of two given streptococcal species revealed a lower level of sequence similarity between their ITS sequences than between their 16S rRNA gene sequences (8, 27). These results indicate that the ITS region might constitute a more discriminative target sequence than the 16S rRNA gene for differentiating closely related species. By 16S rRNA gene sequencing, Bosshard et al. (6) found that as much as 19% of isolates of aerobic catalase-negative gram-positive cocci could be identified only to the genus level. The ITS region has been suggested as a suitable target for bacterial identification by some investigators (20, 40, 47). A major disadvantage of this approach is the limited number of ITS sequences in public databases. However, the numbers of ITS sequences in public databases have increased in recent years. In 2006, software was developed to analyze bacterial ITS sequences (11).

Although most probes used in this study were designed from the ITS regions, advantage was taken to utilize divergent regions at the 3′ ends of the 16S rRNA genes that were coamplified with the ITS regions by PCR. The following sets of type strains display high ITS sequence identities: E. casseliflavus and Enterococcus flavescens (99.6%); the three subspecies (subsp. gallolyticus, subsp. macedonicus, and subsp. pasteurianus) of S. gallolyticus (94 to 99.6%); S. infantis and S. pneumoniae (96%); S. infantis and S. mitis (96%); S. mitis and S. pneumoniae (99%); and S. salivarius, Streptococcus thermophilus, and S. vestibularis (98 to 99%) (our unpublished data). For this reason, a combination of group-specific and supplemental probes was used to differentiate these closely related species. An extreme example was the differentiation of the three members in the salivarius group (S. salivarius, S. thermophilus, and S. vestibularis). All three species hybridized to two group-specific probes, Sinfsa1 and Ssal, and unequivocal identification of the three species was based on their differential hybridizations to three supplemental probes, S16SC, S16ST, and Stv (Table 2; Fig. 2), creating a unique hybridization pattern for each of the three species.

S. pneumoniae, S. oralis, and S. mitis are related species and difficult to be differentiated by sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene (6, 27). Phylogenetic trees constructed by using the genes encoding 16S rRNA (5, 27), sodA (37, 38), groESL (51), and the ITS region (8) grouped S. mitis and S. pneumoniae together. The interspecies similarities of the ITS sequences between S. mitis and S. pneumoniae could be higher than intraspecies similarities of both species (8). In our previous study, strains of S. pneumoniae cross-hybridized to probes used to identify S. mitis (9). However, differentiation of S. mitis and S. pneumoniae was achieved here by their differential hybridization to two supplemental probes, Smgmo1 and Smgp1 (Table 2; Fig. 2). S. mitis produced positive hybridization with the probe Smgmo1, while S. pneumoniae was positive with another probe, Smgp1.

E. casseliflavus and E. flavescens shared a group-specific probe, Ecas, and could not be differentiated from each other by array hybridization (Table 2; Fig. 2). Strains of E. casseliflavus and E. flavescens are motile, intrinsically vancomycin resistant (possessing the vanC genotype), and able to produce pigments (49). E. casseliflavus and E. flavescens also could not be distinguished from each other by using the tRNA intergenic spacer PCR technique (2). The two species are most probably synonymous, as is also apparent from several other studies (13, 48).

The S. bovis complex comprises a heterogeneous group of bacteria that belong to group D of the Lancefield classification. Phenotypic characterization leads to a further subdivision of S. bovis strains based on their biotype. Biotype I comprises mannitol-positive strains, whereas biotype II comprises mannitol-negative strains (45). S. bovis biotype I is responsible for human endocarditis associated with colonic cancer (33, 52), and this was highly correlated with an underlying colonic neoplasm compared with bacteremia due to S. bovis biotype II (42). Therefore, careful identification of streptococcal bacteremic isolates as S. bovis biotype I provides clinically important information. Recently, S. gallolyticus of the S. bovis complex was proposed to contain three subspecies: S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus (S. bovis biotype I), S. gallolyticus subsp. macedonicus, and S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus (S. bovis biotype II) (44). Members of the S. bovis complex were successfully identified to the species or subspecies level in this study.

The Tm values of probes used in this study varied to a large degree (from 27.7 to 60.5°C), and many probes had Tm values lower than the hybridization temperature (45°C) (Table 2). Although some probes produced relatively weak hybridization, clear signals were obtained for almost all species tested (Fig. 2). This might be partially due to the use of relatively low-stringency washing buffer (2× SSC-0.1% SDS) after hybridization. Volokhov et al. (54) also reported the successful use of probes having Tm values significantly lower than the hybridization temperature for identification of Listeria species. It has been found that the addition of low numbers of 3′ thymine bases can improve the hybridization signal of oligonucleotide probes that failed to show detectable hybridization to target DNA or gave weak hybridization signals. Although the mechanisms of the effect of adding low numbers of thymine bases are not clear, it was proposed that this could increase the binding of probes to the nylon membrane and thus the hybridization intensity (1, 7).

In conclusion, species identification of Abiotrophia, Enterococcus, Granulicatella, and Streptococcus by the present array is highly reliable. With the exception of beta-hemolytic streptococci, the method could be used as an accurate alternative to the conventional methods if adequate species identification is of concern.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants (NSC 95-2323-B006-007 and NSC 95-2320-B-006-034) from the National Science Council and in part by the Department of Medical Research in National Taiwan University Hospital, Taiwan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 October 2006.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anthony, R. M., T. J. Brown, and G. L. French. 2000. Rapid diagnosis of bacteremia by universal amplification of 23S ribosomal DNA followed by hybridization to an oligonucleotide array. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:781-788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baele, M., P. Baele, M. Vaneechoutte, V. Storms, P. Butaye, L. A. Devriese, G. Verschraegen, M. Gillis, and F. Haesebrouck. 2000. Application of tRNA intergenic spacer PCR for identification of Enterococcus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4201-4207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baele, M., V. Storms, F. Haesebrouck, L. A. Devriese, M. Gillis, G. Verschraegen, T. de Baere, and M. Vaneechoutte. 2001. Application and evaluation of the interlaboratory reproducibility of tRNA intergenic length polymorphism analysis (tDNA-PCR) for identification of Streptococcus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1436-1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beighton, D., J. M. Hardie, and A. Whiley. 1991. A scheme for the identification of viridans streptococci. J. Med. Microbiol. 35:367-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bentley, R. W., J. A. Leigh, and M. D. Collins. 1991. Intrageneric structure of Streptococcus based on comparative analysis of small-subunit rRNA sequences. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41:487-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosshard, P. P., S. Abels, M. Altwegg, E. C. Böttger, and R. Zbinden. 2004. Comparison of conventional and molecular methods for identification of aerobic catalase-negative gram-positive cocci in the clinical laboratory. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2065-2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, T. J., and R. M. Anthony. 2000. The addition of low numbers of 3′ thymine bases can be used to improve the hybridization signal of oligonucleotides for use within arrays on nylon supports. J. Microbiol. Methods 42:203-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, C. C., L. J. Teng, and T. C. Chang. 2004. Identification of clinically relevant viridans streptococci by sequence analysis of the 16S-23S rDNA spacer region. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2651-2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, C. C., L. J. Teng, S. K. Tsao, and T. C. Chang. 2005. Identification of clinically relevant viridans streptococci by an oligonucleotide array. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1515-1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarridge, J. E., III, S. M. Attorri, Q. Zhang, and J. Bartell. 2001. 16S ribosomal DNA sequence analysis distinguishes biotypes of Streptococcus bovis: Streptococcus bovis biotype II/2 is a separate genospecies and the predominant clinical isolate in adult males. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1549-1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Auria, G., R., Pushker, and F. Rodriguez-Valera. 2006. IWoCS: analyzing ribosomal intergenic transcribed spacers configuration and taxonomic relationships. Bioinformatics 22:527-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Gheldre, Y. D., P. Vandamme, H. Goossens, and M. J. Struelens. 1999. Identification of clinically relevant viridans streptococci by analysis of transfer DNA intergenic spacer length polymorphism. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:1591-1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Descheemaeker, P., C. Lammens, B. Pot, P. Vandamme, and H. Goossens. 1997. Evaluation of arbitrarily primed PCR analysis and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of large genomic DNA fragments for identification of enterococci important in human medicine. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:555-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drancourt, M., V. Roux, P. E. Fournier, and D. Raoult. 2004. rpoB gene sequence-based identification of aerobic gram-positive cocci of the genera Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Gemella, Abiotrophia, and Granulicatella. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:497-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Facklam, R. 2002. What happed to the streptococci: overview of taxonomic and nomenclature changes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:613-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.French, G. L., H. Talsania, J. R. Charlton, and I. Phillips. 1989. A physiological classification of viridans streptococci by use of the API-20 STREP system. J. Med. Microbiol. 28:275-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukushima, M., K. Kakinuma, H. Hayashi, H. Nagai, K. Ito, and R. Kawaguchi. 2003. Detection and identification of Mycobacterium species isolates by DNA microarray. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2605-2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garnier, F., G. Gerbaud, P. Courvalin, and M. Galimand. 1997. Identification of clinically relevant viridans group streptococci to the species level by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2337-2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gürtler, V., and V. A. Stanisich. 1996. New approaches to typing and identification of bacteria using the 16S-23S rDNA spacer region. Microbiology 142:3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamid, M. E., A. Roth, O. Landt, R. M. Kroppenstedt, M. Goodfellow, and H. Mauch. 2002. Differentiation between Mycobacterium farcinogenes and Mycobacterium senegalense strains based on 16S-23S ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer sequences. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:707-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hassan, A. A., I. U. Khan, A. Abdulmawjood, and C. Lammler. 2003. Inter- and intraspecies variations of the 16S-23S rDNA intergenic spacer region of various streptococcal species. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 26:97-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higashide, T., M. Takahashi, A. Kobayashi, S. Ohkubo, M. Sakurai, Y. Shirao, T. Tamura, and K. Sugiyama. 2005. Endophthalmitis caused by Enterococcus mundtii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1475-1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinnebusch, C. J., D. M. Nikolai, and D. A. Bruckner. 1991. Comparison of API Rapid Strep, Baxter MicroScan Rapid Pos ID Panel, BBL Minitek Differential Identification System, IDS RapID STR System, and Vitek GPI to conventional biochemical tests for identification of viridans streptococci. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 96:459-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoshino, T., T. Fujiwara, and M. Kilian. 2005. Use of phylogenetic and phenotypic analyses to identify nonhemolytic streptococci isolated from bacteremic patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:6073-6085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Innings, Å., M. Krabbe, M. Ullberg, and B. Herrmann. 2005. Identification of 43 Streptococcus species by pyrosequencing analysis of the rnpB gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5983-5991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs, J. A., C. S. Schot, A. E. Bunschoten, and L. M. Schouls. 1996. Rapid species identification of “Streptococcus milleri” strains by line blot hybridization: identification of a distinct 16S rRNA population closely related to Streptococcus constellatus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:1717-1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawamura, Y., X. G. Hou, F. Sultana, H. Miura, and T. Ezaki. 1995. Determination of 16S rRNA sequences of Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus gordonii and phylogenetic relationships among members of the genus Streptococcus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:406-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kikuchi, K., T. Enari, K. Totsuka, and K. Shimizu. 1995. Comparison of phenotypic characteristics, DNA-DNA hybridization results, and results with a commercial rapid biochemical and enzymatic reaction system for identification of viridans group streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1215-1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin, M. C., A. H. Hunag, H. Y. Tsen, H. C. Wong, and T. C. Chang. 2005. Use of oligonucleotide array for identification of six foodborne pathogens and Pseudomonas aeruginosa grown on selective media. J. Food Prot. 68:2278-2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mendoza, M., H. Meugnier, M. Bes, J. Etienne, and J. Freney. 1998. Identification of Staphylococcus species by 16S-23S rDNA intergenic spacer PCR analysis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:1049-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Millar, B. C., X. Jiru, J. E. Moore, and J. A. Earle. 2000. A simple and sensitive method to extract bacterial, yeast and fungal DNA from blood culture material. J. Microbiol. Methods 42:139-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitterer, G., M. Huber, E. Leidinger, C. Kirisits, W. Lubitz, M. W. Mueller, and W. M. Schmidt. 2004. Microarray-based identification of bacteria in clinical samples by solid-phase PCR amplification of 23S ribosomal DNA sequences J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1048-1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osawa, R., T. Fujisawa, and L. I. Sly. 1995. Streptococcus gallolyticus sp. nov.; gallate degrading organisms formerly assigned to Streptococcus bovis. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 18:74-78. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park, H., H. Jang, E. Song, C. L. Chang, M. Lee, S. Jeong, J. Park, B. Kang, and C. Kim. 2005. Detection and genotyping of Mycobacterium species from clinical isolates and specimens by oligonucleotide array. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1782-1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel, R., K. E. Piper, M. S. Rouse, J. M. Steckelberg, J. R. Uhl, P. Kohner, M. K. Hopkins, F. R. Cockerill III, and B. C. Kline. 1998. Determination of 16S rRNA sequences of enterococci and application to species identification of nonmotile Enterococcus gallinarum isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3399-3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Picard, F. J., D. Ke, D. K. Boudreau, M. Boissinot, A. Huletsky, D. Richard, M. Ouellette, P. H. Roy, and M. G. Bergeron. 2004. Use of tuf sequences for genus-specific PCR detection and phylogenetic analysis of 28 streptococcal species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3686-3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poyart, C., G. Quesnes, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 2000. Sequencing the gene encoding manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase for rapid species identification of enterococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:415-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poyart, C., G. Quesne, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 2002. Taxonomic dissection of the Streptococcus bovis group by analysis of manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase gene (sodA) sequences: reclassification of ‘Streptococcus infantarius subsp. coli ’ as Streptococcus lutetiensis sp. nov. and of Streptococcus bovis biotype 11.2 as Streptococcus pasteurianus sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:1247-1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Relman, D. A. 1993. Universal bacterial 16S rDNA amplification and sequencing, p. 489-495. In D. H. Persing, T. F. Smith, F. C. Tenover, and T. J. White (ed.), Diagnostic molecular microbiology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 40.Roth, A., M. Fischer, M. E. Hamid, S. Michalke, W. Ludwig, and H. Mauch. 1998. Differentiation of phylogenetically related slowly growing mycobacteria based on 16S-23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer sequences. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:139-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruoff, K. L., R. A. Whiley, and D. Beighton. 2003. Streptococcus, p. 405-421. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, J. H. Jorgensen, M. A. Pfaller, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 8th ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 42.Ruoff, K. L., S. I. Miller, C. V. Garner, M. J. Farraro, and S. B. Calderwood. 1989. Bacteremia with Streptococcus bovis and Streptococcus salivarius: clinical correlates of more accurate identification of isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:305-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanguinetti, M., L. Novarese, B. Posteraro, S. Ranno, E. De Carolis, G. Pecorini, B. Lucignano, F. Ardito, and G. Fadda. 2005. Use of microelectronic array technology for rapid identification of clinically relevant mycobacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:6189-6193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schlegel, L., F. Grimont, E. Ageron, P. A. Grimont, and A. Bouvet. 2003. Reappraisal of the taxonomy of the Streptococcus bovis/Streptococcus equinus complex and related species: description of Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus subsp. nov., S. gallolyticus subsp. macedonicus subsp. nov. and S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus subsp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:631-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlegel, L., F. Grimont, M. D. Collins, B. Regnault, P. A. D. Grimont, and A. Bouvet. 2000. Streptococcus infantarius sp. nov., Streptococcus infantarius subsp. infantarius subsp. nov. and Streptococcus infantarius subsp. coli subsp. nov., isolated from humans and food. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:1425-1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sherman, J. M. 1937. The streptococci. Bacteriol. Rev. 1:3-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suffys, P. N., A. da Silva Rochaqq, M. de Oliveira, C. E. Dias Campos, A. M. Werneck Barreto, F. Portaels, L. Rigouts, G. Wouters, G. Jannes, G. van Reybroeck, W. Mijs, and B. Vanderborght. 2001. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level using INNO-LiPA mycobacteria, a reverse hybridization assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4477-4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Teixeira, L. M., M. G. Carvalho, V. L. Merquior, A. G. Steigerwalt, M. G. Teixeira, D. J. Brenner, and R. R. Facklam. 1997. Recent approaches on the taxonomy of the enterococci and some related microorganisms. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 418:397-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teixeira, L. M., and R. R. Facklam. 2003. Enterococcus, p. 422-433. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, J. H. Jorgensen, M. A. Pfaller, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 8th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 50.Teng, L. J., P. R. Hsueh, Y. C. Chen, S. W. Ho, and K. T. Luh. 1998. Antimicrobial susceptibility of viridans group streptococci in Taiwan with an emphasis on the high rates of resistance to penicillin and macrolides in Streptococcus oralis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 41:621-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teng, L. J., P. R. Hsueh, J. C. Tsai, P. W. Chen, J. C. Hsu, H. C. Lai, C. N. Lee, and S. W. Ho. 2002. groESL sequence determination, phylogenetic analysis, and species differentiation for viridans group streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3172-3178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tripodi, M. F., L. E. Adinolfi, E. Ragone, E. Durante Mangoni, R. Fortunato, D. Iarussi, G. Ruggiero, and R. Utili. 2004. Streptococcus bovis endocarditis and its association with chronic liver disease: an underestimated risk factor. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:1394-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Volokhov, D., V. Chizhikov, K. Chumakov, and A. Rasooly. 2003. Microarray-based identification of thermophilic Campylobacter jejuni, C. coli, C. lari, and C. upsaliensis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4071-4080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Volokhov, D., A. Rasooly, K. Chumakov, and V. Chizhikov. 2002. Identification of Listeria species by microarray-based assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4720-4728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whiley, R. A., B. Duke, J. M. Hardie, and L. M. C. Hall. 1995. Heterogeneity among 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacers of species within the “Streptococcus milleri group”. Microbiology 141:1461-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.