Abstract

We present the first clinical report of a Staphylococcus pseudintermedius infection in a human. Biochemically, S. pseudintermedius can be easily misidentified as S. aureus. Therefore, the final microbiological identification requires the combination of phenotypic and genotypic tests.

CASE REPORT

A 60-year-old male patient was referred to our center because of ischemic cardiomyopathy and ventricle tachycardia, for which he had received an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) in January 2004. In addition, his medical history comprised arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and a prostate carcinoma. In August 2005, he presented with complaints of migration of the ICD device. No other symptoms of note were elicited. The patient was hemodynamically stable and afebrile (body temperature of 36.7°C). Hematological investigations revealed a hemoglobin level and platelet and leukocyte counts within the normal ranges. His C-reactive protein level was slightly increased, at 1.61 mg/liter (normal, 0 to 5 mg/liter). Clinical examination revealed a perforation of the ICD pocket. Infection was suspected by the presence of pus in the eroded pocket. The infected ICD was surgically removed, and several samples (the ventricular lead, pus, and a tissue sample from the pocket) were sent for culture.

Gram staining of the pus showed gram-positive cocci. The specimens were plated onto sheep blood agar (BioMérieux, Benelux S.A./N.V.) and chocolate agar (BioMérieux), both incubated at 37°C in air supplemented with 5% CO2, and mannitol salt lipovitellinase agar (homemade), MacConkey agar (BioMérieux), and D-Coccosel agar (BioMérieux), all incubated at 37°C in air. In addition, thioglycolate broth (BD, Belgium) was inoculated and incubated at 37°C in air.

After 18 h of incubation, staphylococci with identical phenotypical appearance were isolated from two of the three ICD samples (lead and pus). An overview of the biochemical characteristics is shown in Table 1. Colonies were β-hemolytic on sheep blood agar; positive for DNase, lipovitellinase, and coagulase (rabbit plasma with EDTA; Remel, Apogent); but negative for clumping factor (rabbit plasma with EDTA), mannitol fermentation, and Pastorex Staph-Plus (Bio-Rad, France) agglutination. Biochemical analyses by Phoenix (software ver-sion V5.10A/V4.11B; BD) and API Staph (BioMérieux) gave a presumptive identification of S. aureus with confidence values of 97% and 88.5%, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics that differentiate S. pseudintermedius from other staphylococcia

| Trait | Score for:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. pseudintermedius | Reference strain

|

|||||

| S. aureus | S. intermedius | S. hyicus | S. schleiferi | S. delphini | ||

| Catalase | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Pigment | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Coagulase | + | + | + | D− | − | + |

| Clumping factor | − | + | D | − | + | − |

| DNase | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| β-Hemolysin | + | D | + | − | + | ND |

| Acetoin (VP)b | + | + | W | − | + | − |

| Pyrrolidinyl arylamidase | + | − | + | − | + | ND |

| Maltose | + | + | −; W | − | − | + |

| Saccharose | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| d-Trehalose | + | + | + | D+ | D | − |

| d-Xylose | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Acriflavine (8 μg/ml) | S | R | S | S | S | S |

| Polymyxin E (10 μg) | R | R | S | R | S | S |

Data for reference taxa are based on those described by Devriese et al. (2). Our strain is phenotypically fully consistent with S. pseudintermedius. Traits are scored as +, positive; −, negative; D, strain dependent; D+, usually positive; D−, usually negative; ND, not determined; W, weak; R, resistant; or S, sensitive.

Presence of acetoin determined by the Voges-Proskauer (VP) test.

In vitro susceptibility testing revealed the isolate to be resistant to penicillin G (MIC, >0.25 mg/liter) but susceptible to oxacillin (MIC, ≤0.25 mg/liter). The MICs of other regularly used test antibiotics were particularly low (data not shown), except for clindamycin and erythromycin, which had MICs of 1 mg/liter and >4 mg/liter, respectively. After undergoing surgical removal of the infected ICD, the patient was treated with flucloxacillin (500 mg four times daily administered orally for 1 week).

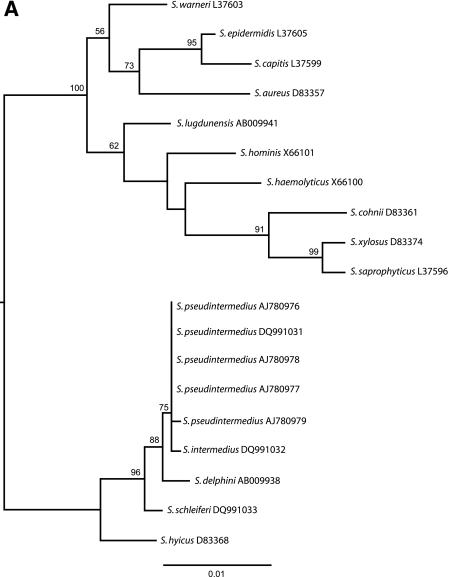

Because of the inconsistent phenotypical identification and the clinical importance of the sample, further identification was performed at the molecular level. DNA was extracted from fresh colonies by heating at 95°C for 15 min in lysis buffer (0.01 M NaOH-0.25% sodium dodecyl sulfate). Two previously described real-time multiplex PCRs (RT-PCRs) were performed targeting the mecA gene and the nuc gene of S. aureus (1) and the tuf gene of the Staphylococcus genus together with the tuf gene specific for S. aureus (6). In addition, we used the DNA as a template for the detection of the coagulase gene of S. aureus by an in-house PCR. The PCRs for the nuc and coagulase genes and the mecA gene of S. aureus were all negative, but the PCR targeting the tuf gene of S. aureus resulted in a positive amplification. Finally, 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis was performed with the DNA extracted from the colonies after PCR amplification, with the primers described by Vaneechoutte et al. (7). The sequences were determined using a CEQ 8000 (Analis S.A./N.V., Belgium) genetic analysis system and aligned with GeneDoc (version 2.6.002). BLAST and phylogenetic analysis (PHYML, version 2.4) resulted in the final identification of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, showing a 16S rRNA gene sequence identical to that previously reported by Devriese et al. (2) (Fig. 1A).

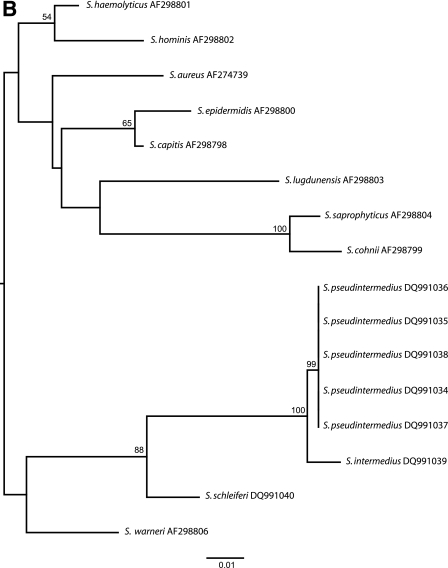

FIG.1.

(A) Maximum likelihood tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Our strain (S. pseudintermedius DQ991031) shows a 16S rRNA gene sequence identical to those previously reported by Devriese et al. (S. pseudintermedius strains AJ780976, AJ780977, AJ780978, and AJ780979). (B) Maximum likelihood tree based on the tuf gene sequences. Our strain (S. pseudintermedius DQ991034) shows 100% sequence similarity with the tuf gene sequences obtained from the S. pseudintermedius strains of Devriese et al. (strains DQ991035, DQ991036, DQ991037, and DQ991038).

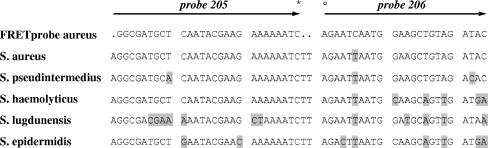

In order to explain the false-positive result of the tuf RT-PCR, a sequence analysis was performed with the tuf gene of our isolate. Because of the absence of a previously reported tuf gene sequence for S. pseudintermedius in GenBank, the analysis was also performed with the four S. pseudintermedius strains obtained from Devriese et al. For the amplification reaction and sequencing reaction, we used the conserved primers as described by Sakai et al. (6). Phylogenetic analysis confirmed the identification of S. pseudintermedius by a 100% sequence similarity with the tuf sequences obtained from the S. pseudintermedius strains of Devriese et al. (Fig. 1B). The false-positive tuf RT-PCR result, however, could not be explained by a phylogenetic relationship between S. pseudintermedius and S. aureus but by the similarities of the tuf gene sequences at the binding sites of the fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) probe used in the RT-PCR assay (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Overview of the mismatches (bases highlighted by black background) between the binding sites of the tuf gene sequences and the FRET probes used in the RT-PCR assay as described by Sakai et al. (6). The fluorescein isothiocyanate label (probe 205) and the LCRED-705 fluorescence dye label (probe 206) are represented by * and °, respectively.

The genus Staphylococcus is currently divided into 38 species and 17 subspecies, half of which are indigenous to humans (4). Staphylococcus pseudintermedius has been recently described as a new coagulase-positive species of animals (2). This case report describes, to our knowledge, the first identification of S. pseudintermedius isolated from a pathological sample from a human. The strain shows several characteristics typical of S. aureus, the most virulent and important pathogen among staphylococci (5). Characteristics of this species include coagulase, DNase, and β-hemolysin production, which confirms the pathogenic potential of this bacterium to cause human disease. The infection described in this case was probably community acquired, but the source of the isolate is not known. It is not known if the patient kept any pets.

Biochemically, Staphylococcus pseudintermedius differs from S. aureus by the lack of pigment and clumping factor activity, a weak and delayed mannitol fermentation, positive reactions for tests for pyrrolidonyl arylamidase and ONPG (β-galactosidase), and sensitivity to 8 μg/ml acriflavine (see comparisons in Table 1). S. pseudintermedius is readily misidentified as S. aureus by commercial identification systems because S. pseudintermedius is not (yet) included in the databases of these products. In agreement with API Staph and Phoenix identification, Staph-Zym (Rosco Diagnostica, Denmark) identifies the species as S. aureus. Vitek 2 software (version VT2-R04.01; BioMérieux, Benelux S.A./N.V.) analysis suggests the identification of S. intermedius with a confidence value of 98.95%. The fact that molecular analysis is also not always conclusive is shown by the false-positive result of the RT-PCR for the tuf gene of S. aureus. The probe used in the RT-PCR to identify S. aureus therefore requires further optimization. When confronted with an inconsistent phenotypical identification pattern, clinical laboratories should consider the use of 16S rRNA gene or tuf gene sequencing for final confirmation (3).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers for the partial 16S rRNA gene sequences of S. pseudintermedius P13431, S. intermedius G30, and S. schleiferi P15880 are DQ991031, DQ991032, and DQ991033, respectively. The GenBank accession numbers for the partial tuf gene sequences of S. pseudintermedius P13431, S. intermedius G30, S. schleiferi P15880, S. pseudintermedius 780976, S. pseudintermedius 780977, S. pseudintermedius 780978, and S. pseudintermedius 780979 are DQ991034, DQ991039, DQ991040, DQ991035, DQ991036, DQ991037, and DQ991038, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Devriese et al. for the donation of their four S. pseudintermedius strains as described in reference 2. We thank P. Lemey for helpful advice on reconstructing phylogenetic trees.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 October 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Costa, A., I. Kay, and S. Palladino. 2005. Rapid detection of mecA and nuc genes in staphylococci by real-time multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 51:13-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devriese, L. A., M. Vancanneyt, M. Baele, M. Vaneechoutte, E. De Graef, C. Snauwaert, I. Cleenwerck, P. Dawyndt, J. Swings, A. Decostere, and F. Haesebrouck. 2005. Staphylococcus pseudintermedius sp. nov., a coagulase-positive species from animals. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55:1569-1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heikens, E., A. Fleer, A. Paauw, A. Florijn, and A. C. Fluit. 2005. Comparison of genotypic and phenotypic methods for species-level identification of clinical isolates of coagulase-negative staphylococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2286-2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kloos, W. E., and T. L. Bannerman. 1994. Update on clinical significance of coagulase-negative staphylococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 7:117-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowy, F. D. 1998. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 339:520-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakai, H., G. W. Procop, N. Kobayashi, D. Togawa, D. A. Wilson, L. Bordon, V. Krebs, and T. W. Bauer. 2004. Simultaneous detection of Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci in positive blood cultures by real-time PCR with two fluorescence resonance energy transfer probe sets. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:5739-5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaneechoutte, M., G. Claeys, S. Steyaert, T. De Baere, R. Peleman, and G. Verschraegen. 2000. Isolation of Moraxella canis from an ulcerated metastatic lymph node. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3870-3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]