Abstract

Histone modifications influence chromatin structure and thus regulate the accessibility of DNA to replication, recombination, repair, and transcription. We show here that the histone deubiquitinating enzyme Ubp10 contributes to the formation/maintenance of silenced chromatin at the rDNA by affecting Sir2p association.

IN eukaryotes, genomic DNA is packaged into chromatin, a nucleoprotein complex whose basic repeating unit is the nucleosome. The nucleosome is made up of 146 bp of DNA wrapped around a histone octamer consisting of two copies each of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 (Luger 2003). Histones are subject to several post-translational modifications such as acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination (Berger 2002; Fischle et al. 2003; Shilatifard 2006). The addition/removal of chemical moieties is a dynamic process that can influence chromatin function by different mechanisms generating sites for interaction with additional proteins or affecting chromatin condensation. Contrary to acetylation, which is globally associated with active chromatin, histone ubiquitination regulates gene transcription in a positive and a negative way, depending on its genomic location (Zhang 2003; Kao et al. 2004; Osley 2004). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae many of the negative effects are observed at telomeres, HM and rDNA loci. In fact, histone H2B is monoubiquitinated at Lys123 by the ubiquitin conjugase Rad6/ligase Bre1 and this modification affects methylation of H3-Lys4 and H3-Lys79 catalyzed by the Set1 and Dot1 methyltransferases, respectively (Ng et al. 2002, 2003; Sun and Allis 2002; Osley 2004). These modifications, which are preferentially localized in euchromatin regions, prevent association of Sir proteins and restrict these factors to heterochromatin regions where they mediate silencing (van Leeuwen and Gottschling 2002; van Leeuwen et al. 2002; Santos-Rosa et al. 2004). Moreover, like histone acetylation, ubiquitination is dynamic. So far, two deubiquitinating enzymes, Ubp8 and Ubp10, have been shown to target monoubiquitinated histone H2B. They display overlapping and distinct functions (Emre and Berger 2006); in particular, the latter is involved in silencing (Kahana and Gottschling 1999; Orlandi et al. 2004). In this context, Ubp10p has been shown to localize at the silenced telomere-proximal loci, where it is responsible for a low level of H2B Lys123 monoubiquitination. Through a trans-histone regulation, Ubp10p cooperates in maintaining a low level of H3 Lys4 and Lys79 methylation, required for proper association of Sir proteins to telomeres (Emre et al. 2005; Gardner et al. 2005). Silent chromatin at chromosome ends contributes to genomic stability since in an open state the telomeres resemble double-strand breaks and elicit DNA repair/recombination activities. Silent chromatin is also a feature of the yeast rDNA locus: a locus highly susceptible to recombination due to its repetitive arrangement and unidirectional mode of DNA replication. Both positive and negative regulatory factors assure an accurate control in the recombination levels of rDNA (Defossez et al. 1999; Kaeberlein et al. 1999; Ivessa et al. 2000; Johzuka and Horiuchi 2002; Versini et al. 2003; Weitao et al. 2003; Blander and Guarente 2004). Sir2p prevents recombination and SIR2 loss of function results in extrachromosomal rDNA circles (ERCs) accumulation.

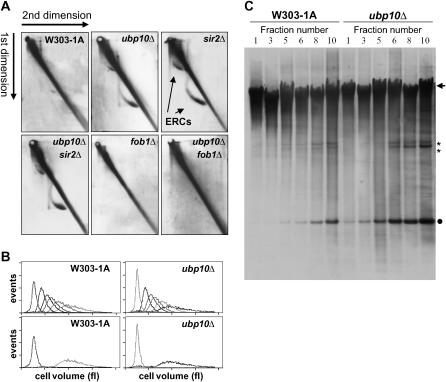

Since Ubp10p is also associated with rDNA regions (Emre et al. 2005), we have investigated here if Ubp10 deubiquitinating activity could be involved in rDNA locus control by examining ERCs as a marker of rDNA recombination, regardless of their role in replicative senescence. All yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Genomic DNAs isolated from sir2, ubp10 null mutants and their isogenic wild-type strain were analyzed by two-dimensional (2D) chloroquine gels and probed for rDNA sequences. Mobilities of both linear and nicked circular DNA are unaffected by chloroquine concentration and they migrate along the diagonal of the gel. Supercoiled DNA circles form arcs that lie off the diagonal with the highly negatively ones running in the lower region of the arc (Sinclair and Guarente 1997). As shown in Figure 1A, ubp10 disruptant cells displayed ERCs accumulation. As a control, the ERCs pattern obtained for a sir2Δ mutant was also shown; this pattern did not change appreciably in the double ubp10 sir2 null mutant.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain name | Relevant genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| W303-1A | MATaade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 can1-100 | |

| ubp10Δ | ubp10Δ∷HIS3 | Orlandi et al. (2004) |

| sir2Δ | sir2Δ∷URA3 | This study |

| fob1Δ | fob1Δ∷KlTRP1 | This study |

| ubp10Δsir2Δ | ubp10Δ sir2Δ∷URA3 | This study |

| ubp10Δfob1Δ | ubp10Δ fob1Δ∷KlTRP1 | This study |

| sir2Δfob1Δ | sir2Δ fob1Δ∷KlTRP1 | This study |

| ubp10Δsir2Δfob1Δ | ubp10Δ sir2Δ fob1Δ∷KlTRP1 | This study |

| W303-1A-SIR2HA | SIR2-3HA∷KlURA3 | This study |

| ubp10Δ-SIR2HA | ubp10Δ SIR2-3HA∷KlURA3 | This study |

All strains are derived from W303-1A. Gene disruption and tagging were performed using PCR-based standard techniques (Baudin et al. 1993; Knop et al. 1999). Following appropriate selection, the accuracy of all gene replacements and correct integration and tagging were verified by PCR with flanking and internal primers. Primer sequences are available upon request. Yeast cells were grown in batches at 30° in Difco (Detroit) yeast nitrogen base without amino acids (YNB-aa, 6.7 g/liter) containing 2% glucose and the required supplements or in 1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto-peptone, 2% glucose (YEPD). Cell number, duplication time, and percentage of budded cells were determined as previously described (Vanoni et al. 1983).

Figure 1.—

ubp10Δ mutants accumulate ERCs. (A) Genomic DNA was prepared using the spheroplast method essentially according to Nasmyth and Reed (1980) and analyzed by 2D gel electrophoresis as described in Sinclair and Guarente (1997). 2D chloroquine gels were run in 15 × 15-cm 1% w/v Tris–acetate–EDTA (TAE) agarose; the first dimension was performed in 0.6 μg/ml chloroquine at 1 V/cm for 39 hr. The second one was performed in 3 μg/ml chloroquine at 1 V/cm for 20 hr. The gels were then transferred onto a positively charged nylon membrane (HybondN; Roche, Indianapolis). Southern analyses were performed using a nonradioactive DNA probe spanning a 25S internal region of 2.4 kb, generated by random priming (DIG-labeling kit, Roche) according to the manufacturer. After hybridization at 50°, blots were washed at 50° as described in Popolo et al. (1993). Two final additional washes were carried out at 68° in 0.2× SSC, 0.1% SDS for 15 min and at room temperature in 0.2× SSC for 2 min. (B) W303-1A and ubp10 cells were elutriated using a Beckman (Fullerton, CA) Avanti J-20 XP expanded-performance centrifuge equipped with a JE-5.0 elutriation system (40-ml chamber) as described in Cipollina et al. (2005) with some modifications. Briefly, appropriately diluted cells were grown for about seven to eight generations and at a density of 5 × 107 cells/ml they were collected by filtration. The elutriation chamber was loaded at a flow rate of 28 ml/min and a rotor speed of 3500 rpm. By progressively decreasing the centrifugation speed, 10 fractions of different-sized cells for each strain were isolated and characterized as described in the text. Cell volume distributions were obtained using a Coulter (Hialeah, FL) Counter particle count and size analyzer, Model Z2, as previously described (Vanoni et al. 1983). Only fractions with the same replicative age were compared: for each strain we selected 6 fractions characterized by well-distinguished volume distributions (top) and by a similar average number of bud scars. Histograms relative to the first and last fractions are also shown (bottom). (C) Genomic DNA was extracted from the elutriated fractions shown in B and analyzed by one-dimensional gel electrophoresis (Sinclair and Guarente 1997). Electrophoresis was performed at room temperature in 15 × 15-cm 0.7% w/v TAE agarose at 1 V/cm for 40 hr. Southern analysis was as in A. ERC monomers (circle) and dimers (asterisks) and the genomic rDNA (arrow) are indicated.

FOB1-dependent replication block causes a DNA double-strand break within the rDNA and this break can be repaired by homologous recombination, resulting in the formation of ERCs. Fob1 mutants have a reduced rate of ERCs formation (Defossez et al. 1999). Deletion of FOB1 reduced ERCs levels in the ubp10 background below those detected in wild-type cells (Figure 1A). An analogous reduction was observed following FOB1 inactivation in the wild-type strain (Figure 1A) in agreement with published data (Defossez et al. 1999; Kaeberlein et al. 1999). The same results were obtained for sir2 fob1 and ubp10 sir2 fob1 null mutants (data not shown). Taken together these data indicate that the sole lack of Ubp10 histone-deubiquitinating activity is able to determine ERCs accumulation and that ERCs are generated by a mechanism depending upon blocked replication forks.

Each rDNA repeat contains an origin of replication that allows the excised DNA circles to behave like autonomously replicating plasmids without a centromeric sequence. A highly asymmetric segregation of ERCs at cell division leads to ERCs accumulation in aged mother cells and assures that daughters are born ERCs free (Sinclair and Guarente 1997). To examine whether UBP10 deletion gave rise to a premature excision of ERCs, we isolated ubp10 mutant and wild-type cells of different replicative ages. Since the increase in size is a defining distinction between young and old cells, both strains were grown for eight generations and then size selected by centrifugal elutriation (Bitterman et al. 2003). Different fractions were collected and characterized by analyzing cell volume distributions (Figure 1B), by counting the number of bud scars after Calcofluor staining, and by determining the percentage of budded cells. In particular, the cell volume distributions of the first and the last elutriated fractions displayed quite separate profiles with different shapes (Figure 1B), in agreement with the presence of two types of cellular populations. Fractions 1 contained uniform populations of small unbudded daughter cells (>90% with no bud scars) with an average cell size of ∼28 fl and 25 fl for the wild-type and ubp10 mutant strains, respectively. Fractions 10 were enriched in large mother cells carrying six to eight bud scars whose broadened cell volume distributions had an average value of 97 fl for the wild-type and 95 fl for ubp10 cells. One-dimensional gel analyses were then performed on DNAs isolated from the different fractions to analyze the presence of ERCs. As shown in Figure 1C, in addition to a strong signal from the genomic rDNA, the rDNA probe detected two ERC species, monomers and dimers; the latter displayed a double band probably due to torsional differences as previously observed (Takeuchi et al. 2003). In young wild-type cells, a very small amount of ERCs was visible; the amount gradually increased along with the size increase. In the ubp10 strain, ERCs levels, as well as the rate of their increase, were higher (Figure 1C), indicating that UBP10 loss of function affects rDNA locus control similarly to SIR2 loss of function.

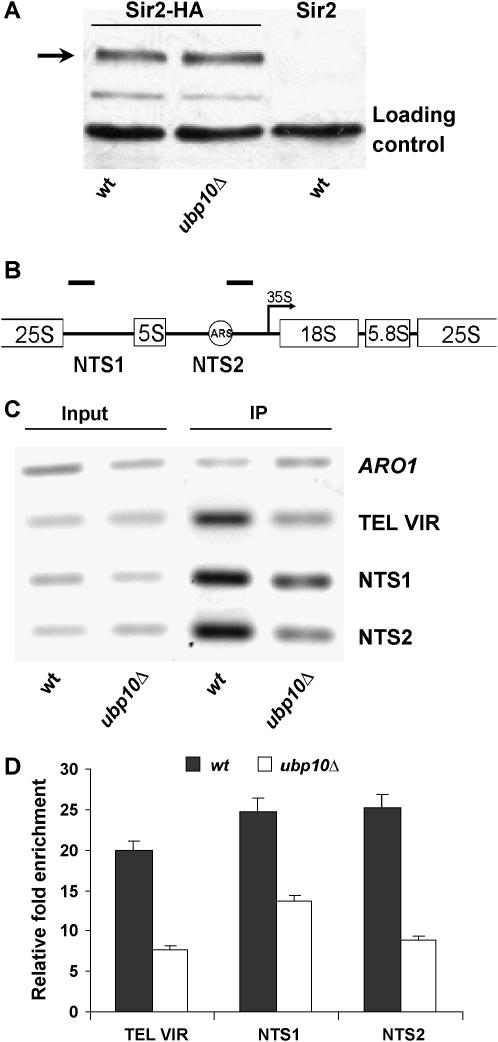

Suppression of recombination occurs through the establishment of a repressive/nonaccessible/silenced structure requiring Sir2 histone-deacetylase activity. Moreover, Ubp10p is required for optimal binding of Sir proteins to telomeres and global telomeric silencing (Orlandi et al. 2004; Emre et al. 2005; Gardner et al. 2005). This finding raised the possibility that Ubp10p might influence Sir2p association with the rDNA locus. Therefore, we generated wild-type and ubp10 strains in which the endogenous copy of SIR2 was epitope tagged at the C terminus, using the 3HA-KlURA3 module (Longtine et al. 1998). Tagged Sir2p was fully functional (see supplemental Figures 1 and 2 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/) and it showed comparable total cellular levels in both strains (Figure 2A). To analyze Sir2p distribution, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments were performed with anti-HA antibodies. Immunoprecipitates (IP), as well as the corresponding whole-cell extracts (input), from each strain were assayed for coprecipitated DNA by PCR with primer pairs that amplify fragments, indicated in Figure 2B, spanning two preferential localization sites of Sir2p within nontranscribed spacer 1 (NTS1) and NTS2 regions of an rDNA repeat (Gotta et al. 1997; Huang and Moazed 2003). A 265-bp fragment located 52 bp from the start of the TG1-3/CA1-3 tract on the right telomere of chromosome VI (TEL VIR) and a 372-bp fragment within ARO1, a nontelomeric gene, were also amplified and used as positive and normalizing controls, respectively. As shown in Figure 2C, in wild-type cells tagged Sir2p was associated with TEL VIR and with both NTS1 and NTS2 regions (Gotta et al. 1997; Strahl-Bolsinger et al. 1997; Suka et al. 2002; Huang and Moazed 2003; Emre et al. 2005). UBP10 deletion affected Sir2p presence not only at the telomere, in agreement with the changes observed by (Emre et al. 2005), but also at the rDNA (Figure 2C). In fact, in the ubp10 strain the amount of amplified PCR products corresponding to NTS1 and NTS2 was reduced, showing, on average, a 1.8- and a 2.8-fold decrease, respectively (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.—

Ubp10p regulates Sir2p association to rDNA. (A) Western analysis of total cellular levels of tagged Sir2p. Total extracts were prepared as in Valdivieso et al. (2000) and protein concentration was determined using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE on 8% polyacrylamide gels. Immunodecoration was carried out as previously described (Valdivieso et al. 2000), using anti-HA monoclonal antibody 12CA5 (Roche) diluted 1:500 in 0.01 m Tris, 0.9% NaCl pH 7.4 (TBS) containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.2% Tween 20. Secondary antibodies were purchased from Amersham and diluted 1:10,000 in TBS, 5% BSA, 0.3% Tween 20. Sir2-HA is indicated (arrow). (B) Schematic representation of the rDNA array; positions of PCR-amplified fragments are indicated by bars. Primer sequences are available upon request. (C) ChIP analysis of Sir2p distribution. ChIP analyses were carried out essentially as described (Fisher et al. 2004). Cells were grown to a cell density of 7 × 106 cells/ml and cross-labeled with 0.1% formaldehyde. Immunoprecipitations of crosslinked DNA were performed with anti-HA monoclonal antibody 12CA5 and Dynabeads Protein A (Dynal Biotech, Great Neck, NY). Immunoprecipitates were washed with 0.025% SDS and assayed for coprecipitated DNA by PCR. DNA was purified by the QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). PCR amplifications were performed from immunoprecipitates (IP) or whole-cell lysate (Input). Serial dilutions of the input DNA establish the linear range of PCR. PCR products were resolved on 2.8% agarose gels and analyzed by Vilber Lourmat Infinity System and Infinity-Capt software. (D) Quantitative analysis of Sir2p association to silent regions. Quantitation was performed by using Scion Image software. Values represent the relative fold enrichments calculated as follows: [TEL VIR or NTS IP/ARO1 IP]/[TEL VIR or NTS input/ARO1 input]. All values are the averages of at least two independent experiments. Standard deviations are indicated.

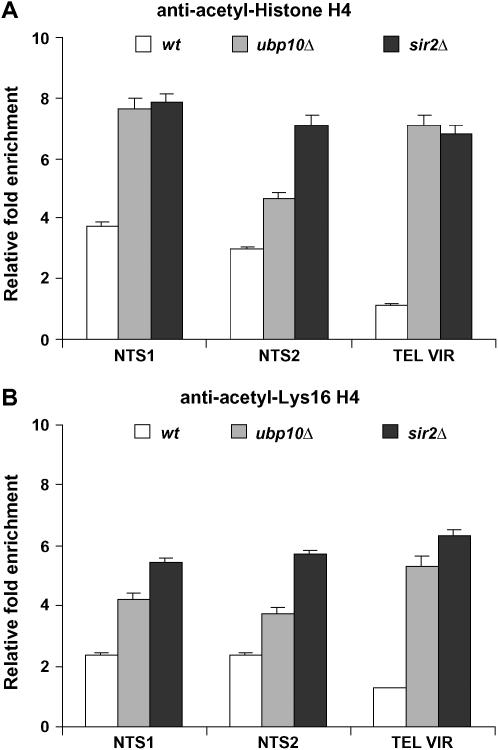

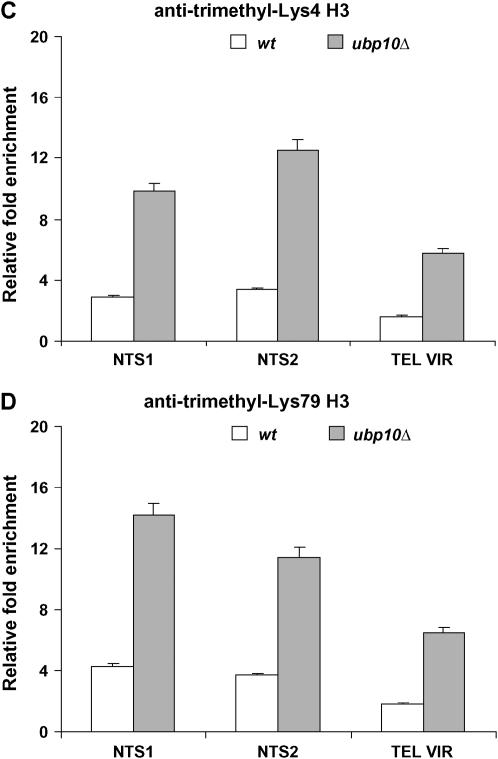

NTS1 and NTS2 are arranged in nucleosomal structures that display hypoacetylation of histone tails in a Sir2p-dependent manner (Armstrong et al. 2002; Bryk et al. 2002; Buck et al. 2002; Hoppe et al. 2002; Huang and Moazed 2003). Given that UBP10 deletion causes a decrease in Sir2p level at the NTS regions, we wondered whether this would correlate to an increase in histone acetylation, as well. In ubp10Δ, sir2Δ, and wild-type strains, ChIP experiments were performed as described above using antibodies that recognize general acetylation of histone H4 tails and the acetylated form of Lys16 of H4 (the target residue of Sir2 deacetylase activity). In addition to the expected results for SIR2 deletion, Figure 3, A and B, shows that UBP10 deletion also increased H4 acetylation at telomere and NTS regions as a likely consequence of the reduction in Sir2p level determined by ChIP (Figure 2). Finally, as a further refinement of our study, we measured Lys4 and Lys79 trimethylation of histone H3. ChIP analyses revealed that the levels of both modifications increased at the two NTS regions in the ubp10Δ mutant compared to those in wild-type cells (Figure 3, C and D). Measurements of H3 Lys4 and Lys79 trimethylation at TEL VIR were also performed as a positive control (Figure 3, C and D) and showed a degree of enrichment in ubp10 cells similar to previously reported data (Emre et al. 2005; Gardner et al. 2005). ChIP analyses performed in HA-tagged strains gave similar results (data not shown).

Figure 3.—

Ubp10Δ mutants display an increase of H4 acetylation and H3 trimethylation levels at silent regions. ChIP analyses were performed as in Figure 2 by using (A) anti-acetyl-histone H4 antibody (06-866; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), (B) anti-acetyl-Lys16 H4 antibody (ab1762, Abcam), (C) anti-trimethyl-Lys4 H3 antibody (ab8580, Abcam), and (D) anti-trimethyl-Lys79 H3 (ab2621, Abcam). Quantitation was performed by using Scion Image software. Values represent the relative fold enrichments calculated as follows: [TEL VIR or NTS IP]/[TEL VIR or NTS input]. All values are the averages of at least two independent experiments. Standard deviations are indicated.

To obtain rDNA silencing, different cellular factors collaborate or compete, leading to an rDNA chromatin structure that is repressive to transcription of a RNA polymerase II reporter gene and recombination (Rusche et al. 2003; Machin et al. 2004; Mueller et al. 2006). We show here that the deubiquitinating enzyme Ubp10 contributes to the formation of such a structure by affecting Sir2p association. rDNA chromatin is highly responsive to alterations in SIR2 dosage and NTS regions represent the major location of SIR2-dependent alterations that have been detected in the rDNA array (Fritze et al. 1997; Smith et al. 1998; Cioci et al. 2002). UBP10 loss of function results in a decrease of Sir2p level at both NTS1 and NTS2 that correlates with histone hyperacetylation and, consequently, produces a more open chromatin configuration. Notably, the NTS1 fragment analyzed overlaps the replication fork block (Kobayashi 2003), suggesting that accumulation of ERCs observed in the ubp10Δ mutant can be ascribed to the reduced extent of Sir2p-dependent silent chromatin required to counteract Fob1p-dependent rDNA recombination at this region.

A Ubp10p requirement for a proper Sir2p localization at the rDNA is consistent with the enrichment of this deubiquitinating enzyme at the locus where it maintains low histone H3 trimethylation (Emre et al. 2005 and this work). Moreover, recalling that Sir4p targets Ubp10p at the telomeres to deubiquitinate H2B by optimizing association of Sir proteins (Gardner et al. 2005), Ubp10p could maintain a proper state of histone modification at the rDNA necessary for Sir2 binding. Clearly, further experiments are needed to determine additional partners involved in Ubp10p recruitment to the rDNA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Fondo per gli Investimenti della Ricerca di Base to L.A. and Fondo d'Ateneo per la Ricerca 2005 to M.V.

References

- Armstrong, C. M., M. Kaeberlein, S. I. Imai and L. Guarente, 2002. Mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene SIR2 can have differential effects on in vivo silencing phenotypes and in vitro histone deacetylation activity. Mol. Biol. Cell 13: 1427–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudin, A., K. O. Ozier, A. Denouel, F. Lacroute and C. Cullin, 1993. A simple and efficient method for direct gene deletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 21: 3329–3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger, S. L., 2002. Histone modifications in transcriptional regulation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12: 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitterman, K., O. Medvedik and D. A. Sinclair, 2003. Longevity regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: linking metabolism, genome stability, and heterochromatin. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67: 376–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blander, G., and L. Guarente, 2004. The Sir2 family of protein deacetylases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73: 417–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk, M., S. D. Briggs, B. D. Strahl, M. J. Curcio and C. D. Allis, 2002. Evidence that Set1, a factor required for methylation of histone H3, regulates rDNA silencing in S. cerevisiae by a Sir2-independent mechanism. Curr. Biol. 12: 165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck, S. W., J. J. Sandmeier and J. S. Smith, 2002. RNA polymerase I propagates unidirectional spreading of rDNA silent chromatin. Cell 111: 1003–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioci, F., M. Vogelauer and G. Camilloni, 2002. Acetylation and accessibility of rDNA chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in Δtop1 and Δsir2 mutants. J. Mol. Biol. 322: 41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipollina, C., L. Alberghina, D. Porro and M. Vai, 2005. SFP1 is involved in cell size modulation in respiro-fermentative growth conditions. Yeast 22: 385–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defossez, P. A., R. Prusty, M. Kaeberlein, S. J. Lin, P. Ferrigno et al., 1999. Elimination of replication block protein Fob1 extends the life span of yeast mother cells. Mol. Cell 3: 447–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emre, T. N. C., and S. L. Berger, 2006. Histone post-translational modifications regulate transcription and silent chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Ernst Schering Res. Found. Workshop 57: 127–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emre, T. N. C., K. Ingvarsdottir, A. Wyce, A. Wood, N. J. Krogan et al., 2005. Maintenance of low histone ubiquitylation by Ubp10 correlates with telomere-proximal Sir2 association and gene silencing. Mol. Cell 17: 585–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle, W., Y. Wang and C. D. Allis, 2003. Histone and chromatin cross-talk. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15: 172–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, T. S., A. K. Taggart and V. A. Zakian, 2004. Cell cycle-dependent regulation of yeast telomerase by Ku. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11: 1198–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritze, C. E., K. Verschueren, R. Strich and R. Easton Esposito, 1997. Direct evidence for SIR2 modulation of chromatin structure in yeast rDNA. EMBO J. 16: 6495–6509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, R. G., Z. W. Nelson and D. E. Gottschling, 2005. Ubp10/Dot4p regulates the persistence of ubiquitinated histone H2B: distinct roles in telomeric silencing and general chromatin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 6123–6139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotta, M., S. Strahl-Bolsinger, H. Renauld, T. Laroche, B. K. Kennedy et al., 1997. Localization of Sir2p: the nucleolus as a compartment for silent information regulators. EMBO J. 16: 3243–3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, G. J., J. C. Tanny, A. D. Rudner, S. A. Gerber, S. Danaie et al., 2002. Steps in assembly of silent chromatin in yeast: Sir3-independent binding of a Sir2/Sir4 complex to silencers and role for Sir2-dependent deacetylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 4167–4180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J., and D. Moazed, 2003. Association of the RENT complex with nontranscribed and coding regions of rDNA and a regional requirement for the replication fork block protein Fob1 in rDNA silencing. Genes Dev. 17: 2162–2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivessa, A. S., J.-Q. Zhou and V. A. Zakian, 2000. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Pif1p DNA helicase and the highly related Rrm3p have opposite effects on replication fork progression in ribosomal DNA. Cell 100: 479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johzuka, K., and T. Horiuchi, 2002. Replication fork block protein, Fob1, acts as an rDNA region specific recombinator in S. cerevisiae. Genes Cells 7: 99–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein, M., M. McVey and L. Guarente, 1999. The SIR2/3/4 complex and SIR2 alone promote longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by two different mechanisms. Genes Dev. 13: 2570–2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana, A., and D. E. Gottschling, 1999. DOT4 links silencing and cell growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19: 6608–6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao, C. F., C. Hillyer, T. Tsukuda, K. Henry, S. Berger et al., 2004. Rad6 plays a role in transcriptional activation through ubiquitylation of histone H2B. Genes Dev. 18: 184–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knop, M., K. Siegers, G. Pereira, W. Zachariae, B. Winsor et al., 1999. Epitope tagging of yeast genes using a PCR-based strategy: more tags and improved practical routines. Yeast 15: 963–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, T., 2003. The replication fork barrier site forms a unique structure with Fob1p and inhibits the replication fork. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 9178–9188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine, M. S., A. Mckenzie, III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach et al., 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14: 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger, K., 2003. Structure and dynamic behaviour of nucleosomes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13: 127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machin, F., K. Paschos, A. Jarmuz, J. Torres-Rosell, C. Pade et al., 2004. Condensin regulates rDNA silencing by modulating nucleolar Sir2p. Curr. Biol. 14: 125–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, J. E., M. Canze and M. Bryk, 2006. The requirement for COMPASS and Paf1 in transcriptional silencing and methylation of histone H3 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 173: 557–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasmyth, K. A., and S. I. Reed, 1980. Isolation of genes by complementation in yeast: molecular cloning of a cell-cycle gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77: 2119–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, H. H., R. M. Xu, Y. Zhang and K. Struhl, 2002. Ubiquitination of histone H2B by Rad6 is required for efficient Dot1-mediated methylation of histone H3 lysine 79. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 34655–34657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, H. H., D. N. Ciccone, K. B. Morshead, M. A. Oettinger and K. Struhl, 2003. Lysine-79 of histone H3 is hypomethylated at silenced loci in yeast and mammalian cells: a potential mechanism for position-effect variegation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 1820–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlandi, I., M. Bettiga, L. Alberghina and M. Vai, 2004. Transcriptional profiling of ubp10 null mutant reveals altered subtelomeric gene expression and insurgence of oxidative stress response. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 6414–6425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osley, M. A., 2004. H2B ubiquitylation: the end is in sight. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1677: 74–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popolo, L., P. Cavadini, M. Vai and L. Alberghina, 1993. Transcript accumulation of the GGP1 gene, encoding a yeast GPI-anchored glycoprotein, is inhibited during arrest in the G1 phase and during sporulation. Curr. Genet. 24: 382–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusche, L. N., A. L. Kirchmaier and J. Rine, 2003. The establishment, inheritance, and function of silenced chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72: 481–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Rosa, H., A. J. Bannister, P. M. Dehe, V. Geli and T. Kouzarides, 2004. Methylation of H3 lysine 4 at euchromatin promotes Sir3p association with heterochromatin. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 47506–47512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilatifard, A., 2006. Chromatin modifications by methylation and ubiquitination: implications in the regulation of gene expression. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75: 243–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, D. A., and L. Guarente, 1997. Extrachromosomal rDNA circle—a cause of aging in yeast. Cell 91: 1033–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. S., C. B. Brachmann, L. Pillus and J. D. Boeke, 1998. Distribution of a limited Sir2 protein pool regulates the strength of yeast rDNA silencing and is modulated by Sir4p. Genetics 149: 1205–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl-Bolsinger, S., A. Hecht, K. Luo and M. Grunstein, 1997. SIR2 and SIR4 interactions differ in core and extended telomeric heterochromatin in yeast. Genes Dev. 11: 83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suka, N., K. Luo and M. Grunstein, 2002. Sir2p and Sas2p opposingly regulate acetylation of yeast histone H4 lysine 16 and spreading of heterochromatin. Nat. Genet. 32: 378–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z. W., and C. D. Allis, 2002. Ubiquitination of histone H2B regulates H3 methylation and gene silencing in yeast. Nature 418: 104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, Y., T. Horiuchi and T. Kobayashi, 2003. Transcription-dependent recombination and the role of fork collision in yeast rDNA. Genes Dev. 17: 1497–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivieso, M. H., L. Ferrario, M. Vai, A. Duran and L. Popolo, 2000. Chitin synthesis in a gas1 mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 182: 4752–4757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, F., and D. E. Gottschling, 2002. Genome-wide histone modifications: gaining specificity by preventing promiscuity. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14: 756–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, F., P. R. Gafken and D. E. Gottschling, 2002. Dot1p modulates silencing in yeast by methylation of the nucleosome core. Cell 109: 745–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanoni, M., M. Vai, L. Popolo and L. Alberghina, 1983. Structural heterogeneity in populations of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 156: 1282–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versini, G., I. Comet, M. Wu, L. Hoopes, E. Schwob et al., 2003. The yeast Sgs1 helicase is differentially required for genomic and ribosomal DNA replication. EMBO J. 22: 1939–1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitao, T., M. Budd and J. L. Campell, 2003. Evidence that yeast SGS1, DNA2, SRS2, and FOB1 interact to maintain rDNA stability. Mutat. Res. 532: 157–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., 2003. Transcriptional regulation by histone ubiquitination and deubiquitination. Genes Dev. 17: 2733–2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]